- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Techniques in Nutrition and Food Science

Effect of Feeding Systems with Different Supplementation on the Profile of Fatty Acids, Amino Acids, Cholesterol and Antioxidants of Milk from Grazing Cows

Galina MA1,2*, Piedrahita R2, Sánchez N1, Pineda J1 and Olmos J3

1Universidad de Colima, México

2FES Cuautitlán, National Autonomous University of México, Mexico

3Universidad de Querétaro, Mexico

*Corresponding author:Miguel Ángel Galina, University of Colima and FES Cuautitlán, National Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico

Submission: December 12, 2025;Published: January 12, 2026

ISSN:2640-9208Volume8 Issue 5

Summary

This study reviews the use of slow intake urea supplementation (SIUS) mixed with probiotics on the profile of fatty acids, amino acids, cholesterol and antioxidant protection of milk from grazing cows. A herd of 60 Suisse cows (511 ± 12kg) in the middle of lactation, 20 were pasturing exclusively over a silvopastoral on star grass (Cynodon plectostachyus) and brachiaria (Brachiaria brizantha), browsing legumes without supplementation (SP). A second group of 20 cows (514 ±14kg) same grazing feeding, were provided with 3kg of SIUS, mixed with 1.5kg of lactobacilli per day as supplement (LAB). The third group of 20 milking cows (544 ±10kg) were supplemented with 6kg/d of a commercial concentrate (COM). Eight commercial milks were also sampled (CM). The milk from the three experimental treatments was weighed each week. Average production was 17kg/d for COM, of 14kg/d in SP and 16kg/d in LAB (P<0.05). The saturated fatty acids and unsaturated fatty acids showed differences in the three treatments (P<0.05). Polyunsaturated fatty acids, omega 3 and conjugated linoleic acid were 34%, 46% and 68% higher in SP, COM and LAB respectively. Results have demonstrated that grazing diverse green fresh forages improve milk quality due to the increase of unsaturated fatty acids. LAB allowed a decrease of biohydrogenation. LAB and SP provided the milk with highest amount of omega 3. In a second observations polyphenols were measured in milk from grazing animals (G) and from milk obtained from ruminants kept in Full Confinement (FC). Samples were analyzed using the superoxide anion test to determine the Degree of Antioxidant Protection (DAP), expressed as the molar ratio between antioxidant compounds and an oxidation target.

Keywords: Probiotic; Quality; Milk; Cows; Tropic; Antioxidants

Introduction

Grasses and some legumes form the basis of animal feed in tropical livestock systems. They are characterized by a group of genera and species with wide adaptation to different environments, known as “plasticity” [1]. Efficient use of these forages is possible when ruminal bacterial populations meet energy requirements, essential nitrogen components, minerals and other nutrients [2]. Otherwise, intake and utilization may be reduced, which can be corrected using ruminal fermentation activators to improve digestive efficiency [3]. The most frequently reported responses to microbial activators in such studies are associated with Volatile Fatty Acid (VFA) production, ruminal pH modification and increased populations of fiber-degrading bacteria [4-6]. Studies on the profile of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), mainly linoleic acid (LA, C18:2 cis-9, cis-12) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA, C18:3 cis-9, cis-12, cis-15), have shown that they can be found in high proportions in forage and some supplement lipids [7,8]. These acids are part of the ruminant diet and, depending on their concentration, modify the fatty acid profile of milk and meat. Their composition is characterized by a higher proportion of unsaturated fatty acids than saturated ones, with saturation increasing due to biohydrogenation (BH) in the rumen [6,9]. Several factors affecting the BH process of LA and ALA have been studied, along with nutritional strategies showing positive results in increasing trans-vaccenic acid (C18:1 trans-11, TVA) and conjugated linoleic acid (C18:2 cis-9, trans-11, CLA) in milk [2]. These compounds have potential health benefits for humans [10-12]. Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) probiotics may be an important alternative, particularly when considering the unsaturated fatty acid profile of the product [2]. In ruminants, microbial flora is responsible for degrading most nutrients, which are later absorbed in the intestine [13]. Consequently, various biotechnological systems have been developed to manipulate the microbiological activities in the bovine fermentation chamber [13]. Unsaturated fatty acids produced during dietary lipid hydrolysis are saturated by ruminal microorganisms through BH, a process requiring H₂ [14-16]. The main substrates for BH are polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), while Conjugated Linoleic Acid (CLA) and transvaccenic acid (trans-11 C18:1, TVA) are key intermediates for ruminal bacteria. CLA is derived from linoleic acid (C18:2) and alpha-linolenic acid (C18:3) [6]. Proper manipulation of ruminal fermentation may increase the primary CLA forms, such as the isomer cis-9, trans-11 C18:2 (c9, t11 CLA) [13]. Since CLA removal as an intermediate depends on BH, it may be possible to enhance this process by providing alternative electron acceptors. Ruminal lactic acid bacteria can utilize these electrons, reducing BH without producing methane [17]. Therefore, studying the effect of LAB supplements on BH is important to improve the milk fatty acid profile [2].

Oxidative stress results from free radical production, such as hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), superoxide (O₂-), singlet oxygen (¹O₂) and hydroxyl radicals (OH•); some are acquired exogenously, while others originate from metabolic processes such as cellular respiration, exposure to microbial infections activating phagocytes, intense physical activity, or the action of pollutants like cigarette smoke, alcohol, ultraviolet radiation, pesticides, coronavirus infection and ozone. Previous studies show that the most oxidation-susceptible substances are polyunsaturated fats, particularly arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid, which produce malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal, recognized markers of lipid oxidation decline. Lipid oxidation also produces aldehydes that affect proteins and can impair their function [17]. Oxidative damage to lipid membrane components has been linked to neurodegeneration, cancer, cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases. Excessive production of reactive oxygen species can lead to oncogene overexpression or the formation of mutagenic compounds causing proatherogenic activity and is associated with senile plaque formation or inflammation [18,19].

The objective of this study was to review advances in ruminal fermentation management, particularly evaluating the effect of LAB supplementation on milk production and its essential fatty acid profile in animals grazing and browsing in a mixed grassland and tropical forest system, with or without Ruminal Fermentation (RF) agents, alone or combined with LAB, compared to commercial concentrate supplementation (COM).

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at “El Fresno” farm, Suchitlán, Colima, at 19°23’ N, 103°41’ W and 1,400m above sea level. According to Köppen, the climate is classified as Aw1 (w), with rains from July to October (1,000mm per year). The dry period lasts 8 to 9 months, with an average temperature of 25 °C. A herd of 35 milking Zebu-cross cows in mid-lactation (511±12kg) was used. The animals grazed in a silvopastoral system (SP) since July, consisting of tropical grasses: star grass (Cynodon plectostachyus) and brachiaria (Brachiaria brizantha), with browsing of legumes in the tropical forest. They were supplemented with 3kg of a ruminal fermentation agent, with or without 1.5kg/day of a Lactic Acid Bacteria probiotic (LAB) during the silvopastoral period. The total grazing area was 20.9ha, with a mixture of tropical grasses: star grass and brachiaria, accompanied by browsing of legumes in the tropical forest. The browsed tropical forest included Mimosa pudica, Plumeria rubra, Bunchosia palmeri, Cordia alliodora, C. dentata, Platymiscium fasiocarpum, Erythroxylum mexicanum, E. rotundifolium, Caesalpinia plumeria, Guettarda elliptica, Randia pitala, Caesalpinia coriaria and Desmodium spp. The stocking rate ranged from 3.6 to 5.9AU/ha. Simultaneously, a second herd of 28 animals (514±14kg) grazed on 16.5ha of a silvopastoral system, supplemented with 6kg of a commercial concentrate per milking cow (160g CP) (COM). Milk from the three treatments was weighed individually each week during the observation period. Weekly samples were taken from each group for fatty acid analysis. During the study, forage availability exceeded the voluntary intake capacity of lactating cows. The probiotic supplementation (LAB) contained approximately 4 x 10⁷ CFU of lactic acid bacteria, from commercial yogurt composed of Lactobacillus plantarum, L. delbrueckii, L. helveticus; Lactococcus lactis, Leuconostoc mesenteroides and Bifidobacterium spp. in a mixture of 35% molasses and 65% cheese whey [2,19-21]. The fermentation promoter (3kg/d) contained a mixture of molasses (18%), cottonseed meal (16%), rice bran (10%), maize (14%), poultry manure (10%), fish meal (8%), beef fat (5%), salt (4%), lime, calcium carbonate (3%), cement (1%), mineral salts (2%), calcium orthophosphate (2%), urea (5%) and ammonium sulfate (2%). Dry matter intake volumes were calculated per cow using representative grazing samples, based on energy and protein requirements for maintenance, growth, milk production and physiological state, according to the milk forage unit system methodology (Jarrige 1995).

Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) analysis was performed by separate extraction using gas chromatography (Varian model 3800) equipped with an automatic sampler (CP 8410) and an FID detector. The chromatograph had a fused silica capillary column (60m, 0.25mm i.d., 0.25μm film; DB-23, J&W Supelco). FAME peaks were identified by comparing retention times with a known mixture of fatty acid standards (Sigma-Aldrich). Volatile compounds were determined using a modified dynamic headspace technique. Samples were purged by bubbling helium and extraction was conducted for 60min with helium at 50mL/min. Volatile components were absorbed into a glass trap filled with 0.20mg of Tenax TA (60/80mesh) and 0.05mg of Carbopack C (40/60mesh). Thermal desorption was performed by heating the trap at 220 °C for 5 minutes with a helium carrier gas flow (50mL/min) in an automatic thermal desorption system (TDS2, Gerstel GmbH). Gas analysis was performed with an Agilent 6890GC connected to a quadrupole Mass Selective Detector (MSD), model 5973. A fused silica capillary column coated with dimethyl polysiloxane (HP-1, Agilent Technologies, USA), 30m, 0.32mm i.d., 0.25μm film thickness, was used to analyze the milk volatile profile. Operating conditions included a helium flow of 1.2mL/min, transfer line to MS at 250 °C and splitless open interface. The temperature program was 10min at 40 °C, with a heating rate of 10 °C/min to 150 °C, held for 12min. The mass spectrometer scanned from m/z 29 to 400 with a cycle time of 0.5s. The ion source was set at 230 °C and spectra were obtained by electron impact (70eV). Detected volatile compounds were identified by comparing mass spectra with Wiley library data (Wiley and Son, Germany). Each sample was analyzed in duplicate. Volatile fatty acid profiles in milk were expressed as percentages. The standard CLA (cis-9, trans-10, cis-12 3%) was obtained from Larodan (Malmö, Sweden). Milk samples (pasture and confinement) were transported on ice and stored at -20 °C until saponification. Superoxide anion was determined spectrophotometrically by incubating cheese with 10μL of 1mg/L nitroblue tetrazolium solution for 30 minutes in the dark. Then, 50μL of dimethyl sulfoxide and 50μL of 2M sodium hydroxide were added. Sample absorbance was measured at 600nm [21].

Results

Results were calculated using an ANOVA model with a completely randomized design:

Yij= μ + ti + Ej

Yij= fatty acid values

μ= general mean

ti= effect of the i-th treatment

Ej= random error effect

i= 1, 2, ..., 4

j= 1, 2, ..., 8

Average milk production was 17.5kg/d (LAB), 14.1kg/d (SP) and 16.5kg/d (COM) (P<0.05). The feeding system significantly affected the fatty acid profile in the studied cows’ milk. This effect was measured by fatty acid content from feeding systems, expressed as percentages of saturated and unsaturated: LAB 66.17:34.04%; SP 65.82:34.23%; COM 67.97:32.30%; CM 67.77:32.35%, as shown in Table 1. Polyunsaturated fatty acid and omega-3 content were LAB 0.51%, SP 0.33% and COM 0.27%, higher than Commercial Milk (CM), which averaged 0.18%. Omega-6 results were 1.77% LAB, 1.59% SP and 1.50% COM, while commercial milk averaged 1.47% (P<0.05). The omega-6/omega-3 ratio was 3.47:1 LAB; 4.82:1 SP; 5.16:1 COM; and 8.17:1 commercial.

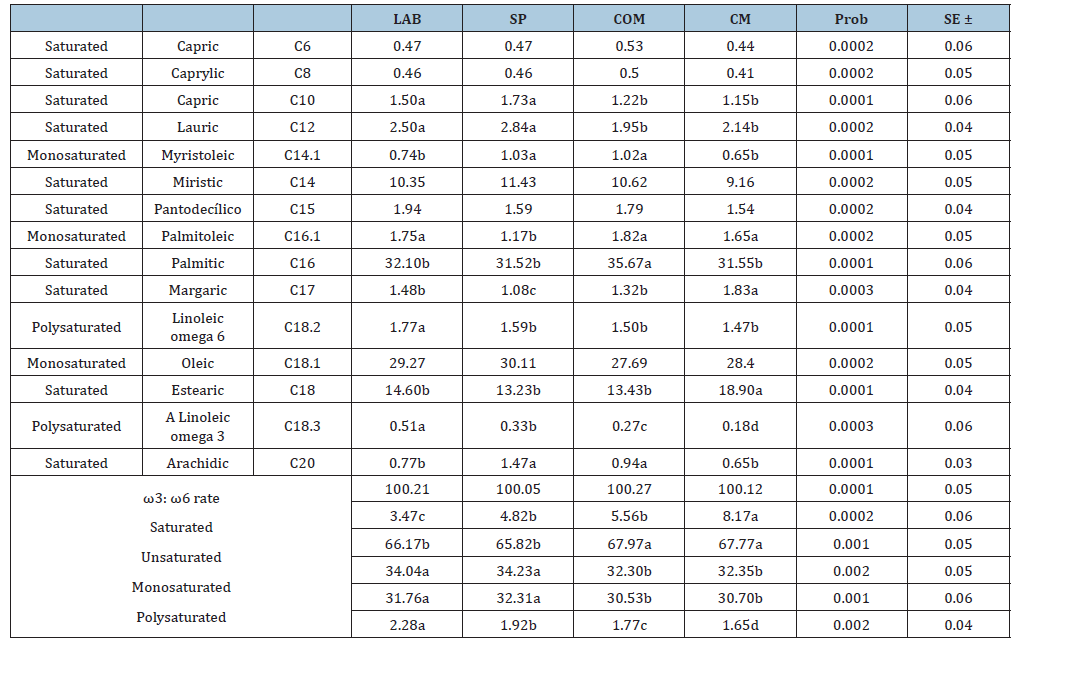

Table 1:Percentages of fatty acids in milk of three silvopastoral treatments with LAB probiotic, silvopastoral (SP), silvopastoral with commercial concentrate (COM) and commercial milk (CM)

a, b, c, d Different letters in the same line indicate significant statistical difference (P<0.05).

LB milk of grazing animals with probiotic.

SP milk of grazing animals.

COM milk of grazing animals with commercial concentrate.

CM commercial milk

Regarding saturated fatty acids, CM and COM were higher than milk from grazing animals, which showed no differences among themselves (P>0.05). Unsaturated fatty acids followed a similar pattern, but LAB and SP were higher than COM (P>0.05). Differences among the four milk types were found in polyunsaturated fatty acid percentages, with intermediate LAB being highest for SP and COM and lowest for CM (P>0.05). Analysis of variance showed that the feeding system modified only the concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids (P<0.01). However, monounsaturated fatty acids were affected (P<0.01) between LAB and SP compared to COM and CM. Regarding polyunsaturated fatty acids, LAB had the highest percentage (P<0.05), superior to other milk types. There was a significant effect (P<0.01) of the feeding system on different milk types.

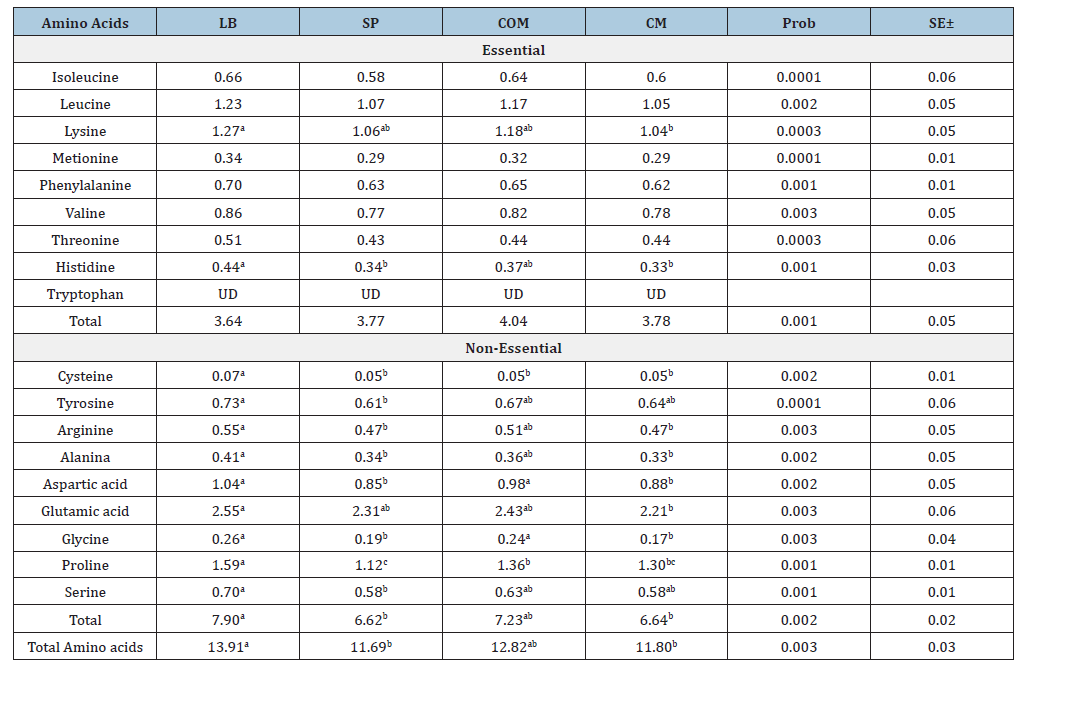

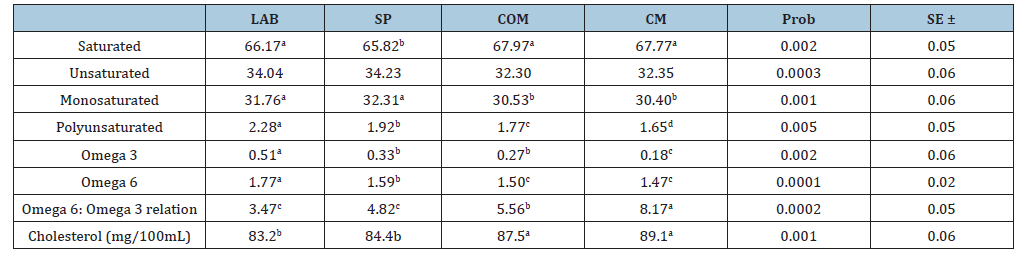

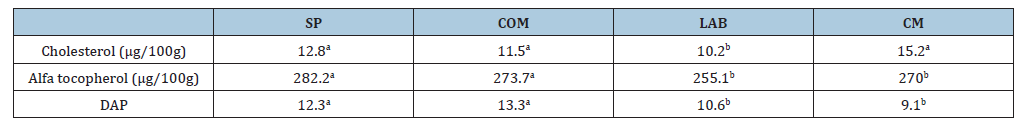

Regarding the amino acid profile (Table 2), significant differences (P<0.05) were found only in lysine and histidine among essential amino acids. However, there was no interaction among factors in the analysis of variance. Lysine concentration was higher in probiotic milk (1.27%) than in CM (1.04%). Histidine was higher in LB (0.44%) than in CM (0.33%) (P<0.05). Table 3 summarizes the content of saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. There is a higher percentage of saturated fatty acids in COM and CM compared to LAB and SP. Particularly important is the difference in omega-3 content, which is higher in pasture milk, especially when supplemented with probiotics. After analyzing cholesterol content in different sample types, LAB recorded 83.2mg/100mL and SP registered 84.4mg/100mL, showing significant differences with COM (87.5mg/100mL) and CM (89.1mg/100mL). Thus, the feeding system, with or without probiotics, showed lower cholesterol content in both treatments. An important element is the omega-6/omega-3 ratio, which in this observation was 3.47 for LAB and 4.82 for SP, slightly below 5, while the same silvopastoral system supplemented with commercial concentrate had a ratio of 5.56:1, likely blocking the beneficial effect of omega-3. The average for commercial milk was 8.17:1, exceeding limits for beneficial human use. Table 4 summarizes that milk (pasture and confinement) was transported on ice and stored at -20 °C until saponification. Superoxide anion was determined spectrophotometrically and cheese was incubated with 10μL of 1mg/L nitroblue tetrazolium solution for 30 minutes in the dark. Then, 50μL of dimethyl sulfoxide and 50μL of 2M sodium hydroxide were added. Sample absorbance was measured at 600nm [21].

Table 2:Amino acids in milk of cows in dry matter (percentage).

a, b,c Different letters in the same line indicate significant statistical difference (P<0.05).

Without letter in the same line indicate that there was no significant statistical difference (P>0.05).

UD=undetermined, LB grazing with probiotic, SP grazing, COM grazing with commercial concentrate, CM commercial

milk.

Table 3:Total concentration of fatty acids in the milk of grazing animals with different supplementation (percentage).

a,b,c Different letters in the same line indicate significant statistical difference (P<0.05), LB milk of grazing animals with probiotic, SP milk of grazing animals, COM milk of grazing animals with commercial concentrate, CM commercial Milk.

Table 4:Polyphenol levels measured with superoxide ion and Antioxidant Protection Levels (DAP) in the milk, in Silvo Pastoral, grazing (SP), animals pasturing with Commercial Concentrate Added (COM), cows in grazing with Lactic Probiotics Supplementation (LAB) and Comercial Milk (CM).

Discussion

Ingestion and rumination performance have been widely documented regarding diet nature, essentially plant maturity and physical form. These aspects can influence organ fill and dry matter degradation rate in the digestive tract [18]. Fermentation Promoters (FP) have been shown to contain elements that improve cell wall utilization due to several factors, including a soluble carbohydrate source providing energy as ATP for anaerobic bacteria [2]. Analysis of ruminal liquor showed pH values of approximately 6.9 with FP use, even though there is no single consensus on the optimal pH for ruminal microbiota function [17-20]. Values found in all treatments were within physiological limits of 6.0 to 7.2, optimal for cellulose digestion, favoring increased growth rates of cellulolytic/hemicellulolytic microorganisms, their enzymatic activity and metabolic products [21]. pH values achieved with FP reflect a positive effect of microbial activators stimulating bacterial growth and contributing to increased DM intake, mainly NDF [2].

Castañeda et al. [22] achieved similar results in goat and sheep performance, showing increased VFA concentrations 2 to 8 hours after feeding. These authors also found a negative correlation (r2=0.454, P<0.01) between pH and organic acid concentrations. Similar performance is possible with RF/LAB use, indicating that the ruminal mixed ecosystem is influenced not only by acid concentration but also by other factors such as medium buffering capacity [2,23]. This likely occurred in these treatments due to increased chewing and rumination, as previously stated, leading to higher saliva production and secretion [24]. The possibility of buffering these substances (carbonates and phosphates), plus urea and amounts of VFAs, acetic and lactic acids contained in LAB and produced in the rumen, along with pH stability, should substantially improve microbial protein synthesis [19] and consequently, animal response. According to Smith [25], ruminal microbial mass can be estimated from VFA concentrations. Studies in Cuba determined an optimum level of 6mL kg LW-1 of LAB in the ration for increased microbial biomass production [24]. This evidences better ruminal fermentation and, consequently, greater degradation of forage enriched in cell walls and microbial mass, which becomes part of digesta as bypass protein with excellent amino acid composition, leaves the rumen and is absorbed in the small intestine [26,27].

Although several in vivo studies describe improvements in DM degradation rate in cattle diets based mainly on fiber with microbial additives from mixed yeast and lactobacilli cultures, such as those by Flores [28] using 1% Lactobacillus plantarum strains in a basic diet containing concentrate and alfalfa, where degradability improvements were obtained. Other studies by Castillo et al. [6] and Gutiérrez [25] evaluated microbial preparations of S. cerevisiae related to ruminal fermentation characteristics in cows fed fibrous diets and found increased cellulolytic and total viable bacteria. With LAB use, there was significant improvement in essential fatty acid content of the animals’ milk [19,29]. However, differences found in DM and NDF intake with the LAB diet compared to other treatments in this study can be attributed to effects similar to those previously achieved in cattle, thus increasing fibrous material disappearance rate in the rumen, as described by Galina et al. [2].

Gutierrez et al. [24] stated that in all treatments with probiotics at different times during incubation kinetics, there were high levels of DM degradation despite high fiber content, although previously it had low digestibility in fibrous forages, defined as low nutritional value materials [25], with high NDF levels and effects on ruminal degradation. Vergara and Araujo [30] found a negative correlation of fiber material with ruminal digestion. Results with LAB in the ration suggest major changes in ruminal microbial activity, resulting in increased fermentation ability of structural carbohydrates by degrading complex carbon chains and releasing simple strings used by cellulolytic bacteria as energy sources for growth from the beginning, plus LAB contribution with peptides and amino acids within its true protein [31]. This is demonstrated during kinetics performance of the curve, where LAB stimulatory activity was observed, perhaps associated with living cells plus their activity in ruminal liquor from the beginning of degradation kinetics and its extension [24].

In studies by Gutierrez et al. [24] with probiotics, response to characteristics during DM degradation kinetics showed that the soluble fraction (A) was the same in all treatments, mainly because the incubated fibrous material was the same (B. brizantha hay). This indicator was estimated from material lost during bag washing at zero hour, without ruminal incubation. In this regard, it can be stated that potential degradation values (A+B) were determined primarily by the insoluble but degradable fraction (B). This fraction, according to Ortíz et al. [32] in studies with grasses, expresses the retention time of this feed type in the rumen and is related to microorganism adaptation and colonization time to degrade this fraction. Simultaneously, there is a high degradation rate (c) of insoluble fraction (B) with values of 2.9h-1. Similarly, the highest Effective Degradability (ED) value of the potentially degradable fraction was determined by the lowest ruminal turnover rate (2% h-1). In the latter, effective degradation decreases with increased ruminal turnover rate. This confirms the importance of using effective degradation rather than potential degradation for diet calculation, as proposed by Leichtle and Cristian [33].

Regarding product quality, the minimum Saturated Fatty Acid (SFA) content was found in grazing animals’ milk, significantly higher when probiotics were added. Literature states that low SFA content may favor human health due to accumulated evidence on blood vessel blockage effects in coronary diseases [34]. Results of the present study explain that the feeding system, in general and specifically free grazing in a silvopastoral system, allows each cow, mainly in forage-diverse areas, to form a diet according to their own needs, positively affecting milk nutritional characteristics, making it health-favorable. The highest trans-fatty acid content was present in grazing milk. Negative effects of trans-fatty acids on health were considered similar to those reported for saturated fatty acids [35] until recently. Negative effects of trans-fatty acids on coronary pathologies and cytotoxicity were determined from observations on hydrogenated fatty acid metabolism produced during industrial feed manufacturing. Trans-fats derived from ruminal biohydrogenation processes, like those produced by the rumen, have demonstrated positive effects on human health [36]. In the present study, this fact was observed for most C18:1 trans-vaccenic acids, through Δ9-desaturation action, where it is metabolized into C18:2 11 trans, 9cis, representing one of the most important beneficial CLA precursors [6]. Therefore, with this relatively new knowledge, the role of trans-fatty acids in ruminant free-grazing feeding systems must be reevaluated for producing “better” milk for consumer health. This fact is of great concern in Mexico because a large part of the population suffers from obesity or overweight, which may translate into degenerative chronic diseases, mainly coronary changes [7].

The beneficial effect of omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated acids has been abundantly documented [36]. New studies have demonstrated the importance of maintaining a ratio lower than 5:1 between omega-6 and omega-3, because higher concentrations block omega-3 beneficial effects, affecting health [7,37]. Only LAB with 3.48 and SP with 4.79 reached this parameter; while grazing supplemented with commercial concentrates was slightly higher (5.54) and the average of 8 commercial milks was 8.40, meaning the limited omega-3 content would have no health effect because it is blocked by omega-6 [37,38]. Although differences were demonstrated between the two systems, omega-3/omega-6 ratio and CLA values were favorable for both systems, demonstrating the importance of biohydrogenation in milk production, which decreases with lactic acid bacteria use. Significant differences in beneficial fatty acid profiles from milk of grazing or stabled animals, with lactic acid bacteria supplementation, compared to commercial milk, demonstrate the importance of biohydrogenation in ruminal metabolism for milk quality and consumer health [2]. BH results with LAB were similar to those obtained in diets supplemented with organic acids or plant oils [36], suggesting that lactic acid bacteria have a ruminal fermentation form with similar effects, resulting in better milk quality [30]. Therefore, several observations have been performed comparing feeding systems in full confinement or grazing with or without lactic acid bacteria supplementation. Significant differences in essential fatty acid profiles among milks from grazing animals with lactic acid bacteria supplementation, compared to commercial milk, demonstrated the importance of BH in ruminal metabolism for milk quality and consumer health. Thus, animals from the silvopastoral system with PF and probiotic supplementation produced significantly better-quality milk compared to grazing without probiotics or stabled animals with or without probiotics, as recently proven [9].

Conclusion

Results demonstrate that the two feeding systems, grazing or full confinement, even if both are mainly composed of fresh green forages, improve milk quality probably due to increased USFA in diets. However, due to decreased BH using LAB, there is production of better-quality milk in its essential fatty acid profile and a favorable significant difference was observed, even compared to SP (P≤0.05). This indicates that decreased BH due to lactic flora reduction occurs when there is a substrate with higher forage diversity, as in LAB animals. Likewise, grazing systems produced milk with lower cholesterol, higher alpha-tocopherol and stronger antioxidant protection. Alpha-tocopherol amount is inversely proportional: Higher in pasture cheeses and lower in stable cheeses. This supports the conclusion that feeding systems directly influence the nutritional and sensory properties of milk and its products, with potential implications for chronic disease prevention.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Colima University and the National Autonomous University of Mexico for their support.

References

- Peters M, Van der Hoek R, Schultze Kraft R, Franco LH, Schmidt A, et al. (2010) Pastures and forage in the tropics: Challenges within the framework of sustainable development. In III Congress on Tropical Animal Production, Havana, Cuba, pp. 1-10.

- Galina MA, Higuera Piedrahita R, Pineda J, Puga DC, Hummel JD, et al. (2020) Effect of lactobacilli symbiotic on rumen, blood, urinary parameters and milk production of Jersey cattle during late pregnancy and early lactation. Novel Techniques in Nutrition and Food Science 5(3): 450-458.

- Galina MA, Piñón JO, Ortiz Rubio A, Higuera Piedrahita RI, De la Cruz H, et al. (2022) Effect of nutritional system on the degree of antioxidant protection of bovine milk. Nov Res Sci 12(3): 1-7.

- Claps S, Galina MA, Rubino R, Pizzillo M, Morone G, et al. (2014) Effect of grazing into the omega 3 and aromatic profile of bovine cheese. J Nutr Ecology and Food Res 2: 1-6.

- Shen X, Dannenberger D, Nuernberg K, Nuernberg G, Zhao R, et al. (2011) Trans‑18:1 and CLA isomers in rumen and duodenal digesta of bulls fed n‑3 and n‑6 PUFA‑based diets. Lipids 46(9): 831-

- Castillo VJ, Olivera AM, Carulla FJ (2013) Description of the biochemical mechanism of polyunsaturated fatty acid ruminal biohydrogenation in the rumen bacteria of animals fed on molasses‑urea diet (Doctoral dissertation). University of Aberdeen, Scotland, p. 180.

- Rubino R (2014) The Latte Nobile model: Another way is possible. Caseus.

- Zened A, Enjalbert F, Nicot MC, Troegeler Meynadier A, et al. (2013) Starch plus sunflower oil addition to the diet of dry dairy cow’s results in a trans‑11 to trans‑10 shift of biohydrogenation. Journal of Dairy Science 96(1): 451-

- Galina MA, Higuera Piedrahita R, Sánchez N, Pineda J, et al. (2025) Bitter taste receptors: A field study to determine polyphenols in cheese. Nov Res Sci 17(1): 1-7.

- Hartfoot CG, Hazlewood GP (1997) Lipid metabolism in the rumen. In: Hobson PN, Stewart CS (Eds.), The rumen microbial ecosystem (2nd edn). Blackie Academic & Professional, pp. 382-426.

- O’Shea M, Lawless F, Stanton C, Devery R (1998) Conjugated linoleic acid in bovine milk fat: A food‑based approach to cancer chemoprevention. Trends in Food Science & Technology 9(5): 192-

- Herrera JA, Shahabuddin AKM, Faisal M, Ersheng G, Wei Y, et al. (2004). Effects of oral supplementation with calcium and conjugated linoleic acid in high-risk primigravids. Colombia Médica 35(1): 31-

- Newbold CJ, López S, Nelson N, Ouda JO, Wallace RJ, et al. (2005) Propionate precursors and other metabolic intermediates as possible alternative electron acceptors to methanogenesis in ruminal fermentation in vitro. British Journal of Nutrition 94(1): 27-35.

- Galina MA, Higuera Piedrahita R, De la Cruz H, Olmos J Vazquez P, Sánchez N, et al. (2023) Effect of feeding system on goat cheese quality. Nov Res Sci 13(1): 1-7.

- Galina MA, Higuera Piedrahita RI, Carrillo S, Musco N, Pineda J, et al. (2021) Effect of feeding systems on bovine milk quality in Mexico. Novel Techniques in Nutrition and Food Science 6(1): 519-523.

- Jin GL, Choi SH, Lee HG, Kim YJ, Song MK, et al. (2008) Effects of Monensin and fish oil on conjugated linoleic acid production by rumen microbes in Holstein cows fed diets supplemented with soybean oil and sodium bicarbonate. Asian Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences 21(12): 1728-1735.

- Calsamiglia S, Ferret A, Devant M (2002) Effects of pH and pH fluctuations on microbial fermentation and nutrient flow from a dual‑flow continuous culture system. Journal of Dairy Science 85(3): 574-

- Van Soest PJ (1982) Nutritional ecology of the ruminant: Ruminant metabolism, nutritional strategies, the cellulolytic fermentation, and the chemistry of forages and plant fibers. OB Books, Inc, p. 24.

- Elías A (1983) Digestion of tropical grasses and forages digestion of tropical grasses and forages. In the pastures of Cuba, Animal Science Institute 2: 187-246.

- Krause KM, Oetzel GR (2006) Understanding and preventing subacute ruminal acidosis in dairy herds: A review. Animal Feed Science and Technology 126(3-4): 215-236.

- Marrero YR (2005) Yeasts as enhancers of ruminal fermentation in high-fiber diets (Doctoral dissertation). Institute of Animal Science. Havana, Cuba, p. 104.

- Castañeda A, Díaz LH, Muro A, Gutiérrez H, García DM, et al. (2010) Rumen fermentation parameters in sheep and goats subjected to dietary changes. In III Congress of Tropical Animal Production and I FOCAL Symposium. Proceedings in electronic format.

- Ramos N, Antonio J (2009) Ruminal acidosis and its relationship with dietary fiber and milk composition in dairy cows. In Advanced Research Seminar Cajamarca, San Marcos Veterinary Research Review System (SIRIVES), pp. 2-3.

- Gutiérrez BR (2005) Probiotic activity of a biofermented product (VITAFER) in broiler chickens (Master’s thesis). Institute of Animal Science, Havana, Cuba, p. 52.

- Smith RH (1975) Nitrogen metabolism in the rumen and the composition and nutritive value of nitrogen compounds entering the duodenum. In: McDonald IW, Warner ACI (Eds.), Digestion and metabolism in the ruminant. University of New England Publishing Unit, pp. 399-415.

- López RJ (2009) Effect of concentrate supplementation on indicators of digestive physiology and nutrient intake in water buffalo calves (Bubalus bubalis) fed star grass (Cynodon nlemfuensis) (Doctoral dissertation). Institute of Animal Science, Havana, Cuba.

- Galindo J, Marrero Y (2005) Manipulation of rumen microbial fermentation. Cuban Journal of Agricultural Science 39: 439-450.

- Flores MN (2000) Preparation of microbial cultures from coconut and their use in diets for fattening sheep (Master’s thesis). National Institute of Nutrition Salvador Zubirán, Mexico.

- Galina MA, Pineda J, Higuera Piedrahita R, Vázquez P, Haenlein GFW, et al. (2019) Effect of grazing on the fatty acid composition of goat’s milk or cheese. Advances in Dairy Research 7(3): 227.

- Vergara López J, Araujo Febres O (2006) Production, chemical composition, and in situ ruminal degradability of Brachiaria humidicola (Rendle) Schweick in the tropical dry forest. Scientific Journal 16(3): 239-248.

- Galina M, Elias A, Vázquez P, Pineda J, Velázquez M, et al. (2016) Effect of the use of fermentation promoters with or without probiotics on the profile of fatty acids, amino acids, and cholesterol of milk from grazing cows. Cuban Journal of Animal Science 50(1): 105-120.

- Ortiz Rubio MA, Ørskov ER, Milne J, Galina MA (2007) Effect of different sources of nitrogen on in situ degradability and feed intake of Zebu cattle fed sugarcane tops (Saccharum officinarum). Animal Feed Science and Technology 139: 143-158.

- Leichtle S, Cristian J (2005) Ruminal degradability of hays from pastures in southern Chile (Undergraduate thesis, Austral University of Chile, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences).

- Secchiari PL (2008) Nutritional and nutraceutical value of foods of animal origin. Italian Journal of Agronomy 3(1): 73-101.

- Wencelová M, Váradyová Z, Mihaliková K, Čobanová K, Plachá I, et al. (2015) Rumen fermentation pattern, lipid metabolism and the microbial community of sheep fed a high-concentrate diet supplemented with a mix of medicinal plants. Small Ruminant Research 125: 64-72.

- Colavilla G, Amadoro C, Mignona R (2014) Omega-6/omega-3 ratio and GPA in Noble Milk in Molise. In Rubino R (Ed.), The Noble Milk Model: Another Way is Possible. Caseus Italia, pp. 118-128.

- Pfeuffer M, Schrezenmeir J (2000) Bioactive substances in milk with properties decreasing risk of cardiovascular diseases. British Journal of Nutrition 84: 155-159.

- Simopoulos AP (2002) The importance of the ratio of omega‑6/omega‑3 essential fatty acids. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 56(8): 365-

© 2025 Galina MA. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)