- Submissions

Full Text

Polymer Science: Peer Review Journal

Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Mechanical Properties of Aramid Ⅲ/CNT Composite Fibers

Fenghao Lu1, Liang Wu2, Yonglong Zhang1, Hongyu He1, Bing Xue1, Mingzhang Sun1, Jijin Mu1, Xiangyang Hao1* and Xinlin Tuo3*

1Engineering Research Center of Ministry of Education for Geological Carbon Storage and Low Carbon Utilization of Resources, Beijing Key Laboratory of Materials Utilization of Nonmetallic Minerals and Solid Wastes, National Laboratory of Mineral Materials, School of Material Sciences and Technology, China University of Geosciences, China

2School of Electronics, Peking University, China

2Key Laboratory of Advanced Materials (Ministry of Education), Department of Chemical Engineering, Tsinghua University, China

*Corresponding author:Xiangyang Hao, Engineering Research Center of Ministry of Education for Geological Carbon Storage and Low Carbon Utilization of Resources, Beijing Key Laboratory of Materials Utilization of Nonmetallic Minerals and Solid Wastes, National Laboratory of Mineral Materials, School of Material Sciences and Technology, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, P R China Xinlin Tuo, Key Laboratory of Advanced Materials (Ministry of Education), Department of Chemical Engineering, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 100084, P R China

Submission: October 23, 2025;Published: November 07, 2025

ISSN: 2770-6613 Volume6 Issue 2

Abstract

The molecular-level reinforcement mechanisms of high-loading SWCNTs in Aramid III fibers, critical for aerospace/defense applications, remain poorly understood. Here, we employ PCFF and GAFF all‑atom MD simulations coupled with bond dissociation energy analysis and Savitzky-Golay filtering to interrogate pristine and 3 wt% SWCNT‑doped Aramid III fibers. Tensile simulations at 10¹⁰s⁻¹ reveal a marked decrease in ultimate tensile stress from 0.80GPa to 0.08GPa upon CNT incorporation, indicating stress‑concentrating aggregates that embrittle the matrix. Bond dissociation energies quantify vulnerable amide linkages (86.0-86.6kcal/mol) versus robust aromatic C-C bonds (126.6kcal/mol). Temperature‑programming studies demonstrate that slow heating (0.15K/ps) stabilizes the interfacial binding energy at -200kcal/mol, ~30kcal/mol higher than rapid heating (-230kcal/mol). Integrating an 180ps NPT equilibration with accelerated heating reduces computational steps by 91.6% (from 1.8×10⁷ to 1.5×10⁶) without compromising stability. Collectively, these findings elucidate the dual stiffeningbrittleness transition induced by high CNT loadings and establish a multiscale MD workflow that balances accuracy and efficiency, offering actionable guidelines for designing advanced CNT‑reinforced polymer fibers.

Keywords:Aramid Ⅲ; SWNT; All-atom molecular dynamics; Tensile properties

Opinion

Aramid III, an advanced polymeric fiber developed through the strategic incorporation of a third monomer into the poly (p-phenylene terephthalamide) backbone, demonstrates superior performance metrics compared to conventional aramid fibers. This structural innovation endows Aramid III fibers with exceptional tensile strength, significantly surpassing that of traditional engineering polymers such as nylon, polyester, and glassreinforced composites [1]. Inheriting the advantageous characteristics of conventional aramid fibers-including low density, high specific strength/stiffness, thermal stability, impact resistance, and radar-wave transparency [2,3]. Aramid III has emerged as a critical material for aerospace engineering, military armor systems, and advanced composite applications [4]. Nevertheless, the mechanical properties of Aramid III, particularly its tensile performance, remain substantially below theoretical predictions, leaving significant room for improvement to meet increasingly demanding application requirements.

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) have garnered significant attention as reinforcing agents in polymer composites due to their unique electrical, thermal, and mechanical properties [5]. Characterized by exceptional specific strength and modulus, CNTs’ nanoscale dimensions and high surface area enable substantial enhancement of matrix performance in composites [5]. Incorporation of CNTs into Aramid III fibers presents a promising strategy to further improve mechanical properties and functional characteristics, thereby expanding application potential. Notably, Luo et al. [6] achieved a 26% tensile performance enhancement in Aramid III through coarse-grained simulations with 0.03wt% amine-functionalized CNTs, while Yan et al. [7] demonstrated a 22% improvement in simulated tensile properties using 0.025 wt% single-walled CNTs. Conventional coarse-grained simulations exhibit inherent limitations in capturing molecular interactions, particularly weak interfacial forces and intramolecular connectivity. All-atom simulations coupled with quantum mechanical calculations enable precise characterization of material behaviors at the atomic scale [8]. During tensile simulations, bond dissociation energy analysis derived from quantum chemical computations proves critical for elucidating mechanical failure mechanisms. Higher dissociation energies indicate chemical bonds with superior resistance to rupture under tension, directly correlating with enhanced fracture toughness; conversely, lower values suggest vulnerable bonds prone to premature failure. This analytical approach not only facilitates structural stability assessment through identification of weak molecular linkages but also provides essential validation for computational models via energy threshold comparisons.

To elucidate the microstructure-property relationship in highconcentration CNT-doped Aramid III fibers, José Cobeña-Reyes et al. [8] conducted complementary analysis using OPLS4 and ReaxFF force fields.

Their comparative validation revealed that all-atom force fields, when properly parameterized, can effectively simulate bond rupture during tensile deformation with computational efficiency comparable to reactive force field methods. This dual-force-field approach not only enables accurate prediction of composite mechanical behavior but also provides critical theoretical guidance for experimental optimization of nanofiber reinforcement systems. We integrate Bond Dissociation Energy (BDE) analysis with all‑atom molecular dynamics simulations under the PCFF and GAFF force fields to interrogate the tensile behavior of both pristine and 3 wt% SWCNT‑doped Aramid III fibers [9,10]. Uniaxial deformation simulations quantify the effects of high‑concentration SWCNT incorporation on tensile stiffness, ultimate strength, and elongation at break, while complementary binding energy calculations-conducted under rapid (10K/ps) and slow (0.15K/ ps) heating protocols-elucidate the influence of thermal history on CNT-polymer interfacial interactions. Furthermore, by mapping vulnerable bond sites identified via BDE computations onto the simulated stress-strain responses, we reveal the molecular origins of defect initiation and reinforcement mechanisms, thereby establishing a robust theoretical framework for the design of high‑loading CNT‑reinforced polymer nanocomposites.

Models and Methods

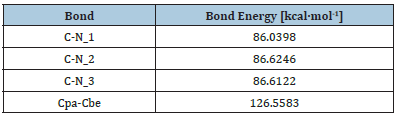

Calculation of bond dissociation energy

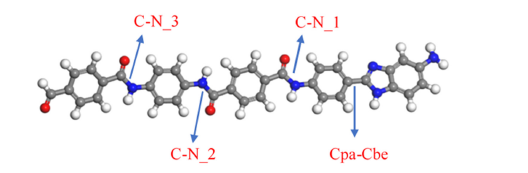

Obabel was used to convert the SMILES string to generate the Aramid III monomer [11]. The molecular structure was preoptimized using MOPAC at the PM6-DH+ level [12-14], and finally, Orca5.0 was employed to calculate the Bond Dissociation Energies (BDEs) of four bonds in the monomer [15]. The preliminary optimized structure facilitates easier geometric convergence and reduces the optimization time under subsequent DFT-level analysis. PM6-DH+ is a modified PM6 method implemented in MOPAC that, compared to previous methods, enhances the description of dispersion interactions and the correction of hydrogen bonds, making it particularly suitable for molecules like Aramid III with strong dispersion effects. Additionally, Korth et al. [12] demonstrated that PM6-DH+ yields slightly improved geometries relative to other semi-empirical methods based on PM6. Geometry optimizations were carried out at the B3LYP-D3/6-31+G* level of theory [16-23], and vibrational analyses were performed at the B3LYP-D3/def2-TZVP level [24]. Previous literature [8,25] has identified the amide bond as having the lowest bond energy in aromatic polyamide structures; therefore, only the changes in bond energy associated with the amide bonds and the newly formed heterocyclic bonds (Figure1) were calculated. Here, the BDE is defined as the standard enthalpy change difference between the whole molecule and its homolytically cleaved fragments. Due to residual discrepancies between Orca-calculated energies and the required thermodynamic enthalpy changes, the Shermo software [26] was used for further thermodynamic calculations. The Orca output files were converted with Multiwfn [27,28], the Shermo temperature was set to 278.5K, and the correction factor was adjusted to 0.9850 [29].

Figure 1:Aramid III monomer with the bonds evaluated in the bond dissociation calculation labeled. C-N_X corresponds to the amide bond at different distances from the heterocyclic ring, and Cpa-Cbe corresponds to the C-C bond between the heterocyclic ring.

Molecular dynamic details

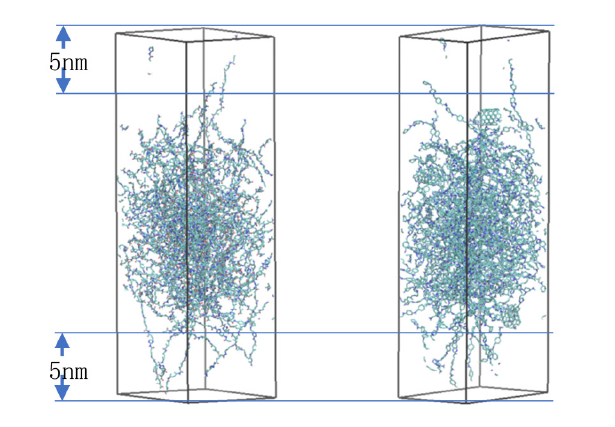

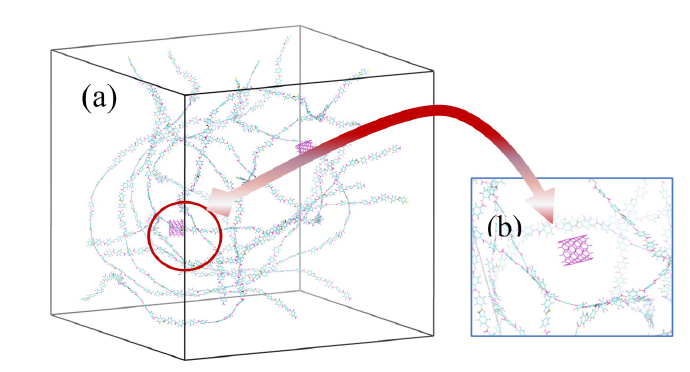

We employed Material Studio 8.0 to construct the polymer model. After performing a Monte Carlo conformational search on the Aramid III molecules, polymerization and model construction were carried out with a Degree of Polymerization (DP) set to 10. To better simulate the one-dimensional nature of fibers, a 5nm vacuum layer was added above and below the model. For precise control of the carbon nanotube content, a weight fraction of 3% was used. As shown in Figure 2, two models were constructed: one containing 62 Aramid Ⅲ molecular chains and another with 62 Aramid chains incorporating 3 carbon nanotubes (Figure 3).

Figure 2:The picture on the left shows pure aramid III fiber. On the right is a simulation diagram of 3 wt% carbon nanotube-doped aramid III fiber.

Figure 3:(a) Initial configuration of aramid III with a size of 20×20×20nm3, which are equivalent to 7120 atoms. (b) Initial position of the carbon nanotube, which contains 100 atoms.

We subsequently performed molecular dynamics simulations using LAMMPS [30]. The model construction and subsequent dynamics calculations employed the CLASS2 version of the PCFF force field, which accurately describes bond, angle, dihedral, and improper interactions and is suitable for complex organic and inorganic molecular systems. Coulomb interactions were treated by the long-range corrected PPPM method. During the simulation, initial velocities were assigned according to the Maxwell distribution, and temperature and pressure were controlled using the NVE, NPT, and NVT integration schemes, respectively, while the neighbor list was updated via binning.

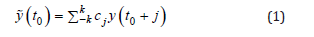

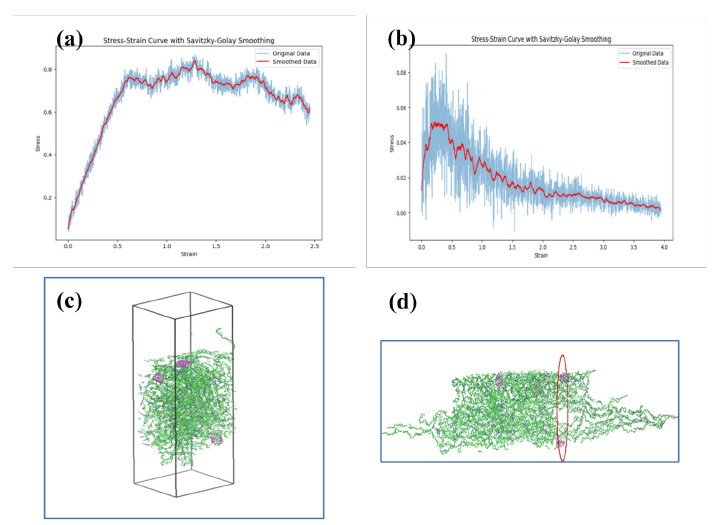

To locate the global minimum energy configuration, we first performed geometry optimization using the conjugate gradient method, followed by initial equilibration of the system under the NVE ensemble with a time step of 0.1fs for 10ps. Thereafter, further equilibration was conducted in the NPT ensemble at 300K under isothermal-isobaric conditions with a time step of 0.1fs for 25ps, using Nosé-Hoover temperature and pressure control [31-33]. A subsequent equilibration was carried out in the NVT ensemble at 300K under isothermal-isochoric conditions with a time step of 0.1fs for 25ps. Tensile simulations were then performed in the NPT ensemble at a strain rate of 10¹⁰s⁻¹ with a time step of 0.05fs over 200,000 steps, corresponding to a tensile strain of 10%. System states and thermodynamic data were periodically output during the simulation to analyze the material’s mechanical behavior and performance under tension. Owing to the potential instability during tensile simulations that may introduce noise into the stressstrain curves, we employed a Savitzky-Golay filter for denoising analysis of the data [34]. The window size was set to 101 (an odd number), and the polynomial order was set to 3. The smoothing process of the Savitzky-Golay filter can be regarded as a convolution process, whereby the raw data are convolved with a specific kernel (i.e., the filter coefficients cj).

In this formulation, y(t0 + j) represents a data point in the original sequence cj, denotes the corresponding convolution kernel (filter coefficients), and y(t0) signifies the filtered data point at position t0. This process mimics the convolution operation in signal processing, where the kernel slides across the signal while computing weighted sums at each position. For Savitzky-Golay filters, the convolution coefficients cj, are specifically derived from the least-squares optimization of polynomial fitting. These optimized coefficients not only determine the smoothing characteristics of the filter but also ensure preservation of the underlying data trends. The essential mechanism of this convolution operation lies in its sliding-window implementation combined with local polynomial fitting, effectively suppressing high-frequency noise components while retaining the low-frequency signal constituents and original trends.

Molecular dynamics simulations of interfacial binding

To investigate the correlation between binding energy and conformational evolution in Carbon Nanotube (CNT)/Aramid III composites, we constructed a 3wt% CNT-incorporated Aramid III model using the GAFF force field. To rigorously quantify the interaction energy of short-fiber CNTs, two CNTs were strategically incorporated within a single system. Given the system’s high rigidity, MMFF94 charges were employed for distribution [35]. Considering the viscoelastic nature of polymers and restricted molecular chain mobility, combined with the computational demands of all-atom force field simulations involving tens of thousands of atoms, the initial configuration was generated using Packmol. This involved random dispersion of 16 aramid chains and two 1-nm CNTs within a 20×20×20nm³ simulation box [36].

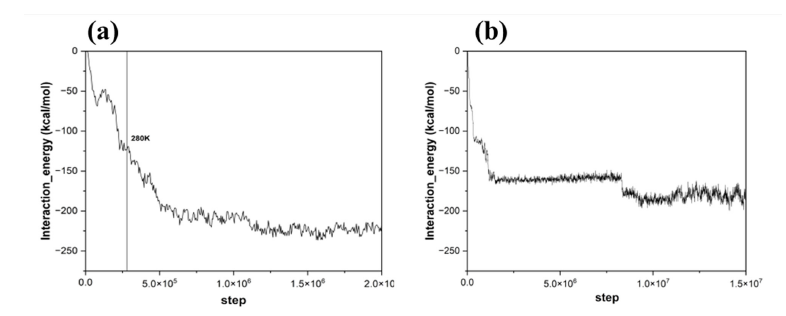

The viscoelastic nature of polymer materials and their restricted molecular mobility become particularly pronounced in molecular dynamics simulations, manifesting as significant conformational changes during initial equilibration - a key rationale for employing Packmol in system configuration. We designed binding energy calculations during this equilibration phase, implementing sequential energy minimization followed by NVE ensemble integration. The system gradually heated from 0K to 280K using the Berendsen thermostat and pressure control strategy [37], while monitoring the interaction energy between Aramid III and CNTs. Two distinct heating rates (0.15K/ps and 10K/ps) were systematically evaluated to probe rate-dependent effects.

Model development via GROMACS-moltemplate integration

Polymer simulations present significant computational challenges due to their inherent memory-intensive nature from high molecular weights, demanding specialized software solutions. Critical force field parameter matching was addressed through complementary use of GROMACS (GROningen MAchine for Chemical Simulation) [38] and LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/ Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator). While GROMACS benefits from extensive automated tools and broad user adoption, LAMMPS excels in materials simulation through comprehensive potential support (e.g., EAM for metals) and versatile deformation capabilities. We developed an interoperability script bridging these platforms via Moltemplate, LAMMPS’s molecular preprocessing tool [39], enabling seamless conversion of GAFF-parameterized GROMACS.gro files into Moltemplate.lt format.

This workflow leverages GROMACS for preliminary treatments (e.g., thermal annealing) followed by efficient NPT equilibration in LAMMPS, capitalizing on each software’s strengths. The conversion process addresses two primary Moltemplate components: molecule.lt for structural definitions and forcefield. lt for interaction parameters. Key transformations involve: (1) Coordinate system adaptation and unit conversion; (2) Force field parameter translation between GROMACS funtypes and LAMMPS styles: GAFF’s harmonic bond stretching (bond_style harmonic), harmonic angle bending (angle_style harmonic), charmm dihedrals (dihedral_style charmm), cvff impropers (improper_style cvff), and Lennard-Jones potentials (pair_style lj/charmm/coul/long). Notably, the script preserves theoretical formulations without modification and currently remains exclusive to the GAFF force field without robustness validation.

Result and Discussion

The calculated bond dissociation energies revealed distinct structural characteristics: three amide bonds exhibited relatively low energies while the Cpa-Cbe bond demonstrated significantly higher strength (126.5583kcal/mol), consistent with LAMMPS MD simulations (C-N< Cpa-Cbe) (Table 1). Under uniaxial tension at 105s- 1 (processed with Savitzky-Golay filtering, Figure 4), the simulated tensile strength showed qualitative agreement despite system size limitations. The ultimate tensile stress decreased markedly from 0.8GPa to 0.08GPa with 3wt% CNT incorporation. As visualized in Figure 4d, localized deformation predominantly occurred near CNTs when employing LAMMPS’s deform module for box-scale stretching. This stress concentration and defect generation at CNT-rich regions correlated with significantly enhanced material rigidity, evidenced by characteristic stress-strain responses that align with reported nanocomposite behaviors [40,41]. Temperature-dependent binding energy evolution during 0-280K heating displayed notable rate effects, as quantified in Figure 5. Distinct heating rates (0.15 vs. 10K/ps) induced measurable variations in interfacial energy profiles, highlighting kinetic influences on composite stabilization.

Table 1:Bond dissociation energies obtained in orca at the B3LYP-D3/def2-tzvplevel of theory show that C-N has the lowest BDE energy.

Figure 4:Tensile stress-strain curve of aramid Ⅲ fiber with different concentration of SWNT. (a) Pure aramid Ⅲ fiber stress-strain curve. (b) 3% concentration of carbon nanotubes doped aramid Ⅲ fiber stress-strain curve. The blue is the original image, and the red curve is after fitting. (c) Stable structure of composite fiber before stretching. (d) Morphology of Aramid Ⅲ composite fiber after stretching.

Figure 5(a) reveals that rapid heating (10K/ps) induces structural instability, though subsequent 180-ps NPT equilibration stabilized the binding energy at -230kcal/mol. Conversely, gradual heating (0.15K/ps) in Figure 5(b) achieves energy stabilization (-200kcal/mol) through progressive molecular rearrangement, indicating spontaneous interfacial equilibrium between the polymer matrix and Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) under optimal dispersion conditions. The ≈30kcal/mol disparity between heating protocols reveals conformation-dependent binding characteristics in polymer nanocomposites. Comparative analysis of Figure 5a & Figure 5b demonstrates that extended equilibration at 280K after rapid heating yields lower binding energy (-230kcal/mol) than slow-heating counterparts (-200kcal/mol). simulation step size is 0.1fs. Heating up to 180K at a rate of 0.15K/ps requires 1.8×107 steps. 10K/ps reaches a sufficiently low binding energy at 1.5×106 steps, and the simulation time is reduced by 91.6%. This suggests accelerated protocols could potentially reduce computational time while requiring careful stability monitoring to prevent simulation collapse. The reduced binding energy under gradual heating conditions (-200kcal/mol) stems from sufficient chain relaxation that minimizes steric hindrance effects, reflecting the timedependent viscoelastic nature of polymers.

Figure 5:(a) A binding energy curve with a warming rate of 10K/ps, the structure is stable in subsequent NPT equilibrium; (b) A binding energy curve with a warming rate of 0.15K/ps, the structure is in equilibrium very early, with only minor adjustments thereafter.

The significant binding energy variations (Δ≈30kcal/ mol) emphasize heating rate’s critical role as a processing parameter. Optimized thermal protocols enable precise control over nanocomposite microstructure through tailored interface engineering, thereby modulating macroscopic material performance. These findings provide crucial guidance for balancing computational efficiency and simulation stability in molecular dynamics studies, while highlighting temperature-programming strategies as key determinants in composite material design.

Conclusion

This study systematically investigates the mechanical enhancement mechanisms of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs) in aramid III fibers through molecular dynamics simulations and bond dissociation energy analysis, revealing a concentration-dependent reinforcement effect where optimal SWCNT incorporation (≤3wt%) improves tensile strength and stiffness while reducing elongation at break, consistent with existing literature, though beyond 3wt%, SWCNT agglomeration generates stress-concentration sites and structural defects, degrading composite strength despite higher interfacial binding energy. Notably, bond dissociation energy calculations identify vulnerable amide bonds (C-N: 86kcal/mol) and robust aromatic linkages (Cpa-Cbe: 126.6±3.4kcal/mol) that correlate with observed tensile failure patterns, while thermal protocol optimization demonstrates that controlled slow heating (0.15K/ps) facilitates polymer chain relaxation, reducing interfacial binding energy by ≈30kcal/mol compared to rapid heating (10K/ps), though strategic combination of accelerated heating with subsequent NPT equilibration (180ps) achieves 91.6% computational time reduction(1.8x107 step into 1.5x106 steps) while maintaining simulation stability. These computational insights establish fundamental structure-property relationships in CNT-reinforced aramid composites, providing a theoretical framework for optimizing high-performance nanocomposites through precise concentration control to prevent agglomeration, thermal history engineering to balance processing efficiency and interface quality, and molecular-scale reinforcement design targeting critical bond types, with the developed multiscale methodology offering a robust approach for designing advanced fiber composites with tailored mechanical performance.

Credit Authorship Contribution Statement

Fenghao Lu Writing - original draft & software. Liang Wu: Writing - original draft. Yonglong Zhang: Writing -original draft. Hongyu He: investigation & data curation. Bing Xue: Funding acquisition, Xiangyang Hao: writing-review & editing, Xinlin Tuo: writing-review & editing. Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgment

The research was funded by China University of Geosciences (Beijing) Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Programme, Category A Project S202311415048. At the same time, we would like to thank you for the help from Shenzhen Shuli Technology Company.

Data Availability

The scripts supporting the articles are available in https:// github.com/Little-slash/gro2mol , The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

References

- Liu Y, Zhang Y, Zhang C, Huang B, Li Y, et al. (2018) Low temperature preparation of highly fluorinated multiwalled carbon nanotubes activated by Fe3O4 to enhance microwave absorbing property. Nanotechnology 29(36): 365703.

- Tikhonov IV, Tokarev AV, Shorin SV, Shchetinin VM, Chernykh TE, et al. (2013) Russian aramid fibres: Past -present -future*. Fibre Chemistry 45: 1-8.

- Penn L, Milanovich F (1979) Raman spectroscopy of kevlar 49 fibre. Polymer 20(1): 31-36.

- Li J, Wen Y, Xiao Z, Wang S, Zhong L, et al. (2022) Holey reduced graphene oxide scaffolded heterocyclic aramid fibers with enhanced mechanical performance. Advanced Functional Materials 32(42): 2200937.

- Zhou X, Liu X, Sansoz F, Shen M (2018) Molecular dynamics simulation on temperature and stain rate-dependent tensile response and failure behavior of Ni-coated CNT/Mg composites. Applied Physics A 124: 506.

- Luo J, Wen Y, Jia X, Lei X, Gao Z, et al. (2023) Fabricating strong and tough aramid fibers by small addition of carbon nanotubes. Nature Communications 14: 3019.

- Yan D, Luo J, Wang S, Han X, Lei X, et al. (2024) Carbon nanotube-directed 7 Gpa heterocyclic aramid fiber and its application in artificial muscles. Advanced Materials 36(22): 2306129.

- Cobeña-Reyes J, Yang Q, Stober ST, Burns AB, Martini A (2023) Probabilistic approach to low strain rate atomistic simulations of ultimate tensile strength of polymer crystals. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 19(18): 6326-6331.

- Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA (2004) Development and testing of a general amber force field. Journal of Computational Chemistry 25(9): 1157-1174.

- Sun H, Mumby SJ, Maple JR, Hangler AT (1994) An AB initio CFF93 all-atom force field for polycarbonates. Journal of the American Chemical Society 116(7): 2978-2987.

- O'boyle NM, Banck M, James CA, Morley C, Vandermeersch T, et al. (2011) Open babel: An open chemical toolbox. Journal of Cheminformatics 3: 33.

- Korth M (2010) Third-generation hydrogen-bonding corrections for semiempirical QM methods and force fields. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 6: 3808-3816.

- Stewart JJP (1990) MOPAC: A semiempirical molecular orbital program. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design 4: 1-103.

- Stewart JJP (2007) Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods V: Modification of NDDO approximations and application to 70 elements. Journal of Molecular Modeling 13: 1173-1213.

- Neese F (2022) Software update: The ORCA program system-version 5.0. WIREs Computational Molecular Science 12(5): e1606.

- Becke AD (1988) Density-functional exchange-energy approximation with correct asymptotic behavior. Physical Review A 38(6): 3098-3100.

- Becke AD (1996) Density‐functional thermochemistry. IV. A new dynamical correlation functional and implications for exact‐exchange mixing. The Journal of Chemical Physics 104(3): 1040-1046.

- Clark T, Chandrasekhar J, Spitznagel GW, Schleyer RVP (1983) Efficient diffuse function-augmented basis sets for anion calculations. III. The 3-21+G basis set for first-row elements, Li-F. Journal of Computational Chemistry 4(3): 294-301.

- Hehre WJ, Ditchfield R, Pople JA (1972) Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XII. Further extensions of gaussian-type basis sets for use in molecular orbital studies of organic molecules. The Journal of Chemical Physics 56: 2257-2261.

- Grimme S, Antony J, Ehrlich S, Krieg H (2010) A consistent and accurate AB initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. The Journal of Chemical Physics 132(15): 154104.

- Grimme S, Ehrlich S, Goerigk L (2011) Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. Journal of Computational Chemistry 32(7): 1456-1465.

- Hariharan PC, Pople JA (1973) The influence of polarization functions on molecular orbital hydrogenation energies. Theoretica Chimica Acta 28: 213-222.

- Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG (1988) Development of the colle-salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Physical Review B 37(2): 785-789.

- Weigend F, Ahlrichs R (2005) Balanced basis sets of split valence, triple zeta valence and quadruple zeta valence quality for H to Rn: Design and assessment of accuracy. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 7: 3297-3305.

- Dorofeeva IB, Kosobutskii VA, Tarakanov OG (1983) Theoretical investigation of the dissociation energy of bonds in urethanes and amides. Journal of Structural Chemistry 23: 534-538.

- Lu T, Chen Q (2021) Shermo: A general code for calculating molecular thermochemistry properties. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 1200: 113249.

- Lu T, Chen F (2012) Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. Journal of Computational Chemistry 33(5): 580-592.

- Lu T, Chen Q (2022) Mwfn: A strict, concise and extensible format for electronic wavefunction storage and exchange. Theoretical and Computational Chemistry.

- Alecu IM, Zheng J, Zhao Y, Truhlar DG (2010) Computational thermochemistry: Scale factor databases and scale factors for vibrational frequencies obtained from electronic model chemistries. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 6(9): 2872-2887.

- Thompson AP, Aktulga HM, Berger R, Bolintineanu DS, Brown WM, et al. (2022) LAMMPS - a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Computer Physics Communications 271: 108171.

- Andersen HC (1980) Molecular dynamics simulations at constant pressure and/or temperature. The Journal of Chemical Physics 72: 2384-2393.

- Hoover WG (1985) Canonical dynamics: Equilibrium phase-space distributions. Physical Review A 31(3): 1695-1697.

- Nosé S (1984) A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. The Journal of Chemical Physics 81: 511-519.

- Steinier J, Termonia Y, Deltour J (1972) Smoothing and differentiation of data by simplified least square procedure. Analytical Chemistry 44(11): 1906-1909.

- Halgren TA (1999) MMFF VI. MMFF94s option for energy minimization studies. Journal of Computational Chemistry 20(7): 720-729.

- Martínez L, Andrade R, Birgin EG Martínez JM (2009) PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of Computational Chemistry 30(13): 2157-2164.

- Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR (1984) Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. The Journal of Chemical Physics 81: 3684-3690.

- Abraham MJ, Murtola T, Schulz R, Páll S, Smith JC, et al. (2015) GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2: 19-25.

- Jewett AI, Stelter D, Lambert J, Saladi SM, Roscioni OM, et al. (2021) Moltemplate: A tool for coarse-grained modeling of complex biological matter and soft condensed matter physics. Journal of Molecular Biology 433(11): 166841.

- Liu K, Macosko CW (2019) Can nanoparticle toughen fiber-reinforced thermosetting polymers? Journal of Materials Science 54: 4471-4483.

- Wang SQ, Fan Z, Gupta C, Siavoshani A, Smith T (2024) Fracture behavior of polymers in plastic and elastomeric states. Macromolecules 57(9): 3875-3900.

© 2025 Xiangyang Hao and Xinlin Tuo. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)