- Submissions

Full Text

Investigations in Gynecology Research & Womens Health

Main Molecular Mechanisms of Fluconazole Resistance in Candida albicans and its Pathogenicity in Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Sebastián Atehortua Giraldo1, Leidy Yurany Cárdenas2 and Ana Elisa Rojas Rodríguez1

1Universidad Católica de Manizales, Colombia

2Universidad de Caldas, Colombia

*Corresponding author:Ana Elisa Rojas Rodríguez, Universidad Católica de Manizales, Manizales, Colombia

Submission:October 21, 2025;Published: December 19, 2025

ISSN: 2577-2015 Volume5 Issue5

Abstract

Introduction: CVV is the most common fungal infection in women of childbearing age. Fluconazole is the main antifungal drug used for the treatment of candidiasis; however, resistance to this pharmacological agent is known to be increasing.

Objective: To describe the main molecular mechanisms involved in fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans species and to determine its role as the main causative agent of CVV.

Methods: An integrative review was performed under the PRISMA methodology and categories of analysis were established to describe the mechanisms of resistance: Ergosterol biosynthesis and efflux pumps. The other category was Candida as a causal agent of CVV.

Results: The molecular resistance mechanisms expressed by C. albicans are mainly overexpression and point mutation of the ERG11 gene, followed by overexpression of the ERG3, CDR1, CDR2 and MDR1 genes. The morphological modification of yeasts to hyphae is the main mechanism responsible for the change from commensal germ to the pathogen in the vulvovaginal mucosa.

Conclusion: Candida albicans is currently the most important pathogen in humans, due to its high rate of colonization and mortality. The literature has focused on describing gene expression and highlights the need for other techniques to evaluate mutations, which may provide greater specificity and relevance in the phenomenon of fluconazole resistance.

Keywords:Candida albicans; Vulvovaginal candidiasis (CVV); Fluconazole; Fungal drug resistance

Introduction

Candida spp are commensal organisms found in healthy hosts as part of the normal microbiota, mainly of the intestine, skin, oropharyngeal cavity, and genital tract. Their epidemiology is variable according to geographical location and groups of affected individuals. Predisposing factors such as immunosuppression, prolonged use of antimicrobial agents, long hospital stays, and inadequate management of therapy are important in the pathophysiology of infection by this yeast [1-4]. Candida albicans is the most studied member of the genus due to its high colonization rates worldwide in immunosuppressed patients, its significant importance as a cause of Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAI), systemic infections leading to death, and its significant role as the main causative agent of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis (CVV). In relation to the above and upon reviewing the literature, it was identified that the resistance of this microorganism to fluconazole has been studied more frequently in India, China, the United States and Brazil [1-6]. CVV is the most common fungal infection in women of childbearing age, it is estimated that it affects 70-75% of these women at least once in their lifetime; and that approximately 5-8% of these women experience recurrent candidiasis; additionally, a percentage between 25-50% of these cases may not manifest clinically, which is called asymptomatic colonization by this fungus. C. albicans has been recognized as the main species causing this clinical picture with an incidence rate of 85-90%; however, other non-albicans Candida species, such as Candida parapsilosis, Candida krusei, Candida tropicalis, Candida glabrata and Candida dubliniensis have become the focus of current research, due to their poor response to treatment and even the development of resistance to the main antifungal agents [3-7].

Several studies have explored the association between candidiasis and preterm delivery, finding that 50% of all preterm deliveries are caused by an ascending genital tract infection, whether due to bacterial, fungal, or parasitic etiology, where C. albicans is an important causal agent of this clinical picture [4,7- 10]. Drugs used in the treatment of mycosis are classified according to the damage they can cause to the cell: fungistatic, which are those that inhibit its growth, and fungicides that cause lysis of the fungus [11-14]. Due to the growing phenomenon of resistance of C. albicans to fluconazole, attempts have been made to elucidate the molecular mechanisms involved in this resistance in order to have a solid basis for the search for improvements in the therapy of infections by this fungus.

Mechanisms have been described such as overexpression of the ERG11 gene, responsible for coding the enzyme lanosterol 14 a-demethylase, which leads to a structural change of the enzyme and subsequently translates into an inability to bind fluconazole to its active site, generating therapeutic rejection. Mutations in this gene have also been related to this phenomenon [15-17]. The overexpression of genes such as CDR1, CDR2, andMDR1 have also been related to the phenomenon of resistance by causing an overproduction of efflux or extrusion pumps, which leads the cell to expel the antifungal agent to the outside [13]. The implication of the ERG3 gene in the phenomenon of resistance is an important topic of study at present, since it is expected that its activity leads the cell to take alternate routes in the biosynthesis of sterols and in turn gives it tolerance to methylated sterols, which is understood as a rejection in the action of fluconazole, some point mutations and higher levels of expression of this gene have also been reported that could be related to the phenomenon of resistance to azoles [13].

Methodology

An integrative search based on the PRISMA method was conducted in the PubMed database, starting from the research question, what are the molecular mechanisms involved in Candida albicans resistance to fluconazole and what is its role as a causative agent of vulvovaginitis? The terms used were Candida albicans, mechanisms resistant, fluconazole (DeCS) // Candida albicans, mechanisms resistant, fluconazole (MeSH) in combination with the Boolean operator AND in “all fields”. Two filters were applied in the advanced database search, from 2012 to 2022 and in humans in order to limit to the most up-to-date output. The search operation was ((Candida albicans) AND (mechanisms resistant) AND (fluconazole)) in June 2022. The term vulvovaginitis was not included, due to the limited number of articles found using this combination, so studies related to vulvovaginal candidiasis were selected by advanced searches with the combination of terms: Candida albicans and vulvovaginitis.

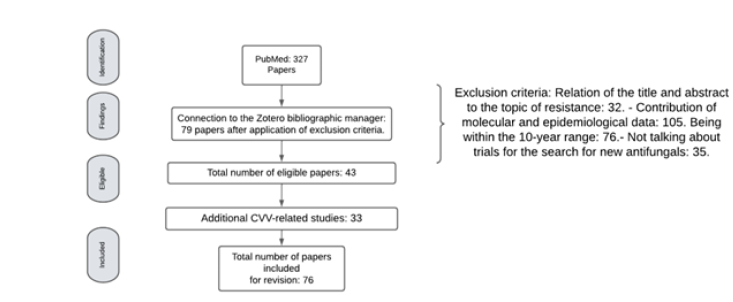

A total of 327 articles were found, the first inclusion criterion considered was that the terms Candida albicans, vulvovaginal candidiasis, molecular mechanisms and fluconazole or any drug belonging to the azole family, should be present in the title or abstract, thus 79 articles were linked to the Zotero bibliographic manager (https://www.zotero.org/). Subsequently, we began reading the abstracts and included articles that provided, in addition to molecular and experimental data, some significant epidemiological figures. Articles that did not address issues related to trials of new substances for the treatment of Candida albicans infections were excluded. Following the duplicate review, a total of 43 articles related to molecular mechanisms of resistance and 33 additional articles on vulvovaginal candidiasis were identified for review.

Figure 1:Paper review process based on the PRISMA method [19].

For this review, three molecular mechanisms involved in the phenomenon of resistance of Candida albicans to fluconazole were determined: Efflux pumps, changes in the therapeutic target by mutation or overexpression of genes and changes in the ergosterol synthesis pathways; although some research included did not refer to the three mechanisms together, it was considered that at least one of them provided information on one of them (Figure 1).

C. albicans and its role as a pathogenic fungus

Candida albicans is a member of the microbiota of healthy humans, it is a diploid polymorphic mucosal surface yeast commonly found in the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and genitourinary tract. It generally behaves as a harmless commensal fungus that can become an opportunistic organism in immunosuppressed patients due to the inability of the immune system to fight infection. In immunocompetent patients, abnormal growth of this microorganism may occur due to environmental imbalance, such as pH reduction or changes in the normal microbiota, unleashing its pathogenic capacity. Under normal conditions, Candida blastoconidia migrate from the lower gastrointestinal tract to the adjacent vaginal vestibule, similar to the colonization route of Lactobacillus; However, Candida colonization occurs in much lower numbers, after adherence to the epithelial cells of the vaginal tract their colonization follows a poorly studied course but is influenced by increased estrogen production after menarche which in turn leads to changes in pH and postmenopausal period decline. At the same time, the immuno-inflammatory response of the mucosa is exacerbated due to the presence of a much higher number of yeasts in the area, causing damage [18-21].

Being a commensal pathogen, C. albicans has the ability to easily adapt to host environmental conditions even when nutrient bioavailability is very restricted [19]. However, infection by this yeast is variable and depends on the immunological conditions of the individual, whether the individual suffers from chronic diseases such as HIV, cancer, or diabetes mellitus, which represent a progressive deterioration of the immune system that results in the inability of the immune system to control the action of almost any type of microorganism present in the individual; hematooncological diseases that lead to marked leukopenias, prolonged antimicrobial therapy that can cause deterioration of the normal microbiota, long hospital stays or any other condition that leads to immunosuppression, are predisposing factors for infection by this yeast. C. albicans is involved as a causal agent of multiple infectious conditions, from systemic infections such as candidemia or colonization of organs essential for survival to superficial mycoses such as atopic dermatitis, vulvovaginal candidiasis, oral candidiasis, among others [19,21-23].

Pathogenesis of C. albicans in mucosal and genital tract infections

The yeast and filamentous phases in C. albicans determine its virulence. The change from yeast to hyphae in this fungus is the morphological change responsible for determining its commensal and pathogenic status, giving it the capacity to cause tissue infection and subsequent dissemination [19,24,25]. The main virulence mechanisms involved in C. albicans infection have been described as its ability to evade macrophages, adhesion to host cells, subsequent production of antagonistic enzymes, and the development of clinically significant biofilms [26,27].

In a study published by Kadosh, 2016 it was determined that the virulence factors of C. albicans are directly related to posttranscriptional mechanisms underlying an imbalance of the metabolic pathways of that microorganism. The commensal state of the fungus is possible due to a tripartite interaction between yeast, resident microbiota, and host immunity; thus, it was determined that when any of the above is modified, it conditions the passage from yeast to hyphae causing mRNA instability and in turn the translation process, this caused by a reduction of oxidative stress at the transcriptional level, which promotes the change in the morphogenesis of C. albicans [19,28-30].

In addition to the molecular patterns exhibited by C. albicans virulence, other mechanisms involved in the activity of this fungus in vivo in causing infections to have been described, for example the B-glucans in the cell wall induce increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines in the infected host and exacerbate tissue damage Cheng et al. [31]. Other research has reported the ability of this yeast to mask and avoid detection by the host immune system and its potential for monocyte reprogramming, which limits the stimulus on the spleen and minimizes the potential for protection [31-38].

Regarding infections of the genitourinary tract, the most relevant virulence factors reported in the literature have to do with the production of proteins and phospholipases, which cause direct damage to the cells that make up the affected tissue [39,40]. In one study, in which early prenatal monitoring was performed between 15 and 20 weeks of pregnancy and in which pharmacological intervention for asymptomatic candidiasis and trichomoniasis and/or bacterial vaginosis was performed, a 46% decrease in preterm delivery was demonstrated in the participants. Similarly, early pharmacological intervention against Candida spp, generated a 49% decrease in the occurrence of preterm delivery, according to the results of a study conducted in New York by Morrison and Cushman, 2007. This highlights the relationship between CVV and preterm delivery, with the importance of timely treatment to prevent it [7,10].

Fluconazole as the main antifungal agent

Fluconazole is the most widely used drug in the treatment of Candida albicans infections; it is a triazole antifungal belonging to the azole family whose main objective is to block the conversion of lanosterol to ergosterol [13,41]. The azoles target the lanosterol demethylase enzyme (lanosterol 14a-demethylase) belonging to the cytochrome p450 enzyme system of the fungus encoded by the ERG11 gene; its main pharmacological action consists of blocking this enzyme, which leads to the interruption of the downstream reactions that give rise to the biosynthesis of ergosterol [13,42]; Specifically, the free hydrogen atom of one of the fluconazole rings binds to an iron atom within the heme group of the enzyme, which prevents the activation of oxygen and, in turn, the demethylation of lanosterol [43]. The enzymatic inhibition is highly toxic for the fungal cell, due to the fact that the methylated sterols accumulate at the level of the cell membrane and stop the growth of the fungus; this is why fluconazole is considered a fungistatic and not fungicidal drug, this allows that when C. albicans is in contact with the treatment for prolonged periods of time it is capable of exhibiting resistance [13,44].

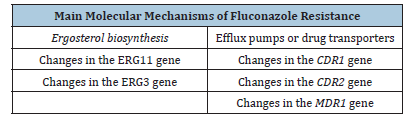

The development of several mechanisms of resistance by C. albicans to fluconazole has been reported in the literature; among the mechanisms identified, mutations or overexpression of genes involved in ergosterol biosynthesis and of genes encoding efflux pumps or drug transporters are involved [13] (Table 1).

Table 1:Main molecular mechanisms of fluconazole resistance.

Mechanisms related to changes in the ERG11 gene

The literature has extensively documented the participation of the ERG11 gene in the resistance of C. albicans to fluconazole; mutations have been described in the coding region of the gene that are related to susceptibility to this drug [15,16].These mutations lead to changes or substitutions in the amino acids that alter the structure and function of the protein, which results in the azole binding site to the pharmacological target being much less stable and efficient [13,17,45].

More than 140 amino acid substitutions have been described in C. albicans related to the ERG11 gene, which highlights the high vulnerability of the enzyme to structural changes [46,47]. For example, changes have been identified in amino acids 105-165, 266-287, and 405-488 that code for lanosterol 14 a-demethylase, which are directly related to the resistance phenomenon [45,48- 50].

The study by Mario F et al. 2010 investigated the impact of 10 specific amino acid substitutions found in clinical isolates of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans and determined by modeling the coding proteins that these substitutions had an impact on fluconazole resistance by preventing drug binding to the catalytic site of the enzyme or to a site on the heme interaction surface in resistant strains; however, this could not be determined in sensitive strains [45,51]. This suggests but does not confirm the cause of fluconazole resistance.

Another mechanism of resistance related to the ERG11 gene reported in the literature has to do with its overexpression, caused by the amplification of transcription during exposure to azole [52- 54]. However, its role is not fully defined and its true relationship with the phenomenon of resistance by C. albicans to fluconazole remains to be determined, as in several related studies such as the one conducted by Victoria K et al. 2012 in which they evaluated the expression of the ERG11 gene in Candida species causing vaginal infections, and in which the species with the highest percentage of incidence corresponded to s it was found that the overexpression of the gene was also present in sensitive and dose-dependent sensitive strains, which suggests that it is not the mechanism responsible for resistance [55,56]. Something similar is evident in the study carried out by Melena A et al. 2015 in which the molecular mechanisms of resistance to fluconazole in clinical isolates of C. albicans from India were evaluated and no relationship was found with the overexpression of the ERG11 gene and the resistance of the fungus, but it was determined that the main cause of resistance in these strains corresponds to overproduction of efflux pumps [57,58].

Alterations in ergosterol biosynthesis (ERG3)

The development of alternate pathways in the biosynthesis of sterols in the cell membrane of C. albicans that result in the development of resistance to fluconazole has been described [13]. This has been attributed to mutations or loss of function of the ERG3 gene, which leads to inactivation of the enzyme 5,6 steroldesaturase and in this way, the cell avoids the production of toxic methylated sterols in the presence of azoles and minimizes the damaging effect of fluconazole at the cellular level [51,57,59].

In a study by Sanglard et al. [41] it was demonstrated that mutations related to ERG3 by deletions cause azole resistance in Candida albicans strains, as well as the overexpression of the gene’s mRNA levels. In this same study, it was suggested that a possible mechanism involved in the resistance phenomenon is that the overexpression of ERG3 increases the synthesis of 5,6 steroldesaturase and, consequently, increases the non-toxic 14a-methylsterol, which accumulates at the membrane level as an intermediate product of the transformation of 14a-methylergoster-824 diene-3 b, 6 a-diol; the latter behaves, under normal conditions of susceptibility, as a cytotoxic compound, which promotes the destruction of the membrane and accelerates cell death; however, when an intermediate product accumulates and is not transformed into the mentioned cytotoxic metabolite, the capacity of resistance is granted to the cell [60,61].

In Feng et al. [61] conducted a study where they analyzed the regulatory role of the ERG3 and Efg1 gene in isolates of C. albicans isolates from patients diagnosed with vulvovaginal candidiasis; they found point mutations when sequencing the gene, two of them were nonsense mutations [C657G (W219C) and C1055T (R352H)], one was a silent mutation (T342G, T435C, C441T and T1047C) and finally one was a mutation in a termination codon [T384C (Stop128 W)], which was responsible for encoding an additional amino acid, which favors the generation of resistance; In addition, they determined that ERG3 gene mRNA levels were much higher in azole-resistant strains [62].

Overexpression and mutation of CDR1, CDR2, and MDR1 genes

In addition to the mechanisms related to the ergosterol biosynthesis pathways, there are others related to efflux pumps or drug extrusion from the interior of C. albicans to the exterior [13]. The purpose of this resistance mechanism is basically to prevent the intracellular accumulation of the drug and with this, the effectiveness as a fungistatic through its action on the drug target. C. albicans has two main classes of efflux pumps or efflux proteins: the Major Facilitator Superfamily (MFS) and the ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter (ABC) superfamily [54].

The proteins belonging to the ABC superfamily are characterized by having a wide substrate specificity and depend on ATP hydrolysis for energy production and therefore their function [63]. 28 of these proteins have been identified in C. albicans and only 2 are well characterized as causing resistance to fluconazole [64,65]. The genes responsible for the production of this mechanism are CDR1 and CDR2, in which it has been identified in several studies that their overexpression leads to a considerable decrease in susceptibility to fluconazole [21,66]. In a study published by Babak P et al. 2017, the expression of efflux pumps in fluconazole-resistant C. albicans isolates was evaluated and overexpression of CDR1 and CDR2 genes was determined in 4 of the 20 isolates evaluated [67].

In contrast, the MFS superfamily has a much narrower range of substrate specificity and is driven primarily by the electrochemical strength of proton exchange [39]. Approximately 95 MFS-type transport proteins have been described in C. albicans, but only one has been linked to fluconazole resistance, Mdr1p [21]. Several studies have observed overexpression of MDR1, which is the coding gene for the MFS-type Mdr1p proteins, in fluconazole-resistant clinical isolates, and its consequent deletion greatly reduces resistance levels; thus, its fundamental role in this phenomenon has been demonstrated [21,54,66]. Pinto A et al. [6] reinforces the previously stated concept by evaluating the MFS-mediated resistance profile of Candida albicans clinical isolates from a tertiary hospital in the Southwest of Brazil, in which they determined the responsibility of MFS-type transporters in fluconazole resistance in fluconazoleresistant C. albicans strains [68].

Discussion

Candida albicans is a pathogenic fungus in humans that has been the main subject of multiple investigations worldwide because of its high mortality rate in immunosuppressed patients, ability to develop systemic mycoses and healthcare-associated infections, localized mycoses such as CVV, and above all, its resistance to antimicrobial therapy [3,5-7]. A large number of studies worldwide have focused on elucidating the phenomenon of resistance to fluconazole attributed to this fungus, due to the imminent need to understand the mechanisms and in general the dynamics associated with resistance, in order to improve treatment regimens and thus have an impact on mortality rates in infections caused by this yeast. The largest number of studies related to the molecular mechanisms of resistance expressed by C. albicans to fluconazole have been carried out in India and Europe, others in the United States and Brazil; however, there is a need to study in detail in various regions of Latin America on the molecular characteristics expressed by this fungus and which are related to resistance to fluconazole, which is frequently used for intervention; In this way, it will be possible to determine with greater precision if the resistance mechanisms are similar or different to those reported in other regions since what is known from research on this phenomenon is that even if it is the same species, each strain has a different molecular expression [5,10,57,58].

Three major molecular mechanisms involved in the resistance of C. albicans to fluconazole have been identified. albicans to fluconazole; studies so far are not definitive in explaining them, for example, the main mechanism described in the literature is related to the ERG11 gene in which point mutations or overexpression are suggested, leading to a change in the structure of the drug target, which ultimately results in loss of affinity of the drug to the target enzyme; However, the literature also reports sensitive strains in which higher levels of gene expression have been determined, calling into question its role as the only mechanism that causes [45,48-50,69]. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out more studies that evaluate in greater detail these molecular characteristics associated with resistance in both sensitive and resistant strains and thus, to better understand the biological phenomenon, as well as to determine if one is more determinant than the other; additionally, it is necessary to establish if the resistance mechanisms are similar or different in different regions of the world.

Another important mechanism described in the literature is related to the overproduction of efflux pumps or drug extrusion from the fungal cell, which leads to therapeutic rejection; however, there is still a long way to go, because although there are a large number of studies that have focused their interest on the analysis of the expression of the genes responsible for coding for the transport proteins CDR1, CDR2, and MDR1, there is little scientific evidence that describes in detail the possible mutations that can present these genes [54,64,65,67].

Finally, regarding the third mechanism described in the literature, which refers to the use of alternative pathways for sterol biosynthesis and is related to the activity of the ERG3 gene for the inactivation of the enzyme 5,6 sterol desaturase, although some point mutations have been determined, it has not been widely studied in terms of the phenomenon of molecular resistance of C. albicans to fluconazole [60-62].

Conclusion

Candida albicans is currently the most important pathogenic fungus in humans due to its high colonization and mortality rates in multiple types of infections. Regarding its role as the main causal agent of CVV, it has been reported as the species with the highest prevalence and has been directly related to recurrence and therapeutic failure; of interest, CVV is associated with abortion and preterm delivery, and prophylaxis with fluconazole has shown significant efficacy in reducing this complication, so it is important to study the phenomenon of resistance so that the intervention with this drug remains in force or other alternatives are considered. Although resistance mechanisms related to changes in the expression and some mutations in the ERG11, ERG3, CDR1, CDR2, and MDR1 genes have been studied with special interest, their unique or dominant participation in the phenomenon of resistance to fluconazole has not been determined with total certainty, since these biological changes have also been found in susceptible strains; This suggests that further studies are required to investigate whether there are complementary and dominant biological phenomena to generate resistance, as well as the sequences responsible for the changes in the genes associated with resistance, in order to deepen the understanding of the molecular basis in a more specific way.

As can be evidenced, the literature that refers to the molecular characteristics of C. albicans associated with resistance to fluconazole, is extensive in the description of the expression and, less frequently, in the description of the mutations of the genes involved in this phenomenon; the latter is a very important aspect because it helps to understand in a more detailed way the particular mechanisms that confer resistance to the genus Candida; From the above, it is evident the need for further studies whose purposes include the detailed description of the molecular mechanisms associated with resistance particularly to fluconazole; in addition, research on this phenomenon in other regions should be conducted to establish whether resistance also involves changes in the genes already reported in other parts of the world or is related to other mechanisms; for example, in Colombia, only one study has been done on C. albicans and it is precisely the research that provides elements on which physicians can analyze to propose the best pharmacological alternative in terms of intervention against Candida spp. infections.

References

- Fox EP, Nobile CJ (2012) A sticky situation: Untangling the transcriptional network controlling biofilm development in Candida albicans. Transcription 3(6): 315-322.

- Lim CSY, Rosli R, Seow HF, Chong PP (2012) Candida and invasive candidiasis: Back to basics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 31(1): 21-31.

- Kim J, Sudbery P (2011) Candida albicans, a major human fungal pathogen. J Microbiol 49(2): 171-177.

- Rivera LEC, Ramos AP, Desgarennes CP (2005) Virulence factors in Candida sp. Dermatology Rev Mex 49: 12-27.

- Yang L, Su MQ, Ma YY, Xin YJ, Han RB, et al. (2016) Epidemiology, species distribution, antifungal susceptibility, and ERG11 mutations of Candida species isolated from pregnant Chinese Han women. Genet Mol Res 15(2).

- Zhang JY, Liu JH, Liu FD, Xia YH, Wang J, et al. (2014) Vulvovaginal candidiasis: Species distribution, fluconazole resistance and drug efflux pump gene overexpression. Mycoses 57(10): 584-591.

- Pinto ACC, Rocha DAS, Moraes DCD, Junqueira ML, Ferreira-Pereira A (2019) Candida albicans clinical isolates from a Southwest Brazilian Tertiary Hospital exhibit MFS-mediated azole resistance profile. An Acad Bras Ciênc 91(3): e20180654.

- Moris DV, Melhem MSC, Martins MA, Souza LR, Kacew S, et al. (2012) Prevalence and antifungal susceptibility of Candida parapsilosis complex isolates collected from oral cavities of HIV-infected individuals. J Med Microbiol 61(12): 1758-1765.

- Okungbowa FI, Isikhuemhen OS, Dede APO (2003) The distribution frequency of Candida species in the genitourinary tract among symptomatic individuals in Nigerian cities. Rev Iberoam Mico 20(2): 60-63.

- Pirotta MV, Garland SM (2006) Genital Candida species detected in samples from women in Melbourne, Australia, before and after treatment with antibiotics. J Clin Microbiol 44(9): 3213-3217.

- López-Ávila K, Dzul-Rosado KR, Lugo-Caballero C, Arias-León JJ, Zavala-Castro JE (2016) Mechanisms of antifungal resistance of azoles in Candida albicans. A review. Rev Biomed 27(3).

- Rivas AM, Castro NC (2009) Antifungals for systemic use: What therapeutic options do we have? Ces Med 23(1): 61-76.

- Chiocchio VM, Matkovi L (2011) Determination of ergosterol in cellular fungi by HPLC. A modified technique. The Journal of the Argentine Chemical Society 98: 10-15.

- Catalán M, Montejo JC (2006) A Systemic antifungals. Pharmacodynamia andpharmacokinetics. Ibero-American Journal of Mycology 23(1): 39-49.

- Gómez Quintero CH (2010) Candida yeast resistance tofluconazole. Infection14(2): 172-180.

- Berkow E, Lockhart S (2017) Fluconazole resistance in Candida species: A current perspective. Infect Drug Resist 10: 237-245.

- Xu Y, Sheng F, Zhao J, Chen L, Li C (2015) ERG11 mutations and expression of resistance genes in fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans Arch Microbiol 197(9): 1087-1093.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097.

- Mane A, Vidhate P, Kusro C, Waman V, Saxena V, et al. (2016) Molecular mechanisms associated with Fluconazole resistance in clinical Candida albicans isolates from India. Mycoses 59(2): 93-100.

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ (2007) Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: A Persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev 20(1): 133-163.

- Whaley SG, Berkow EL, Rybak JM, Nishimoto AT, Barker KS, et al. (2017) Azole antifungal resistance in candida albicans and emerging non-albicans candida Front Microbiol 7: 2173.

- Gunsalus KTW, Tornberg-Belanger SN, Matthan NR, Lichtenstein AH, Kumamoto CA (2016) Manipulation of host diet to reduce gastrointestinal colonization by the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans. mSphere 1(1): e00020-15.

- Thompson DS, Carlisle PL, Kadosh D (2011) Coevolution of morphology and virulence in candida Eukaryot Cell 10(9): 1173-1182.

- Sobel JD (2016) Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 214(1): 15-21.

- Sobel JD (2007) Vulvovaginal candidosis. The Lancet 369(9577): 1961-1971.

- Ilkit M, Guzel AB (2011) The epidemiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidosis: A mycological perspective. Crit Rev Microbiol 37(3): 250-261.

- Donders G, Bellen G, Byttebier G, Verguts L, Hinoul P, et al. (2008) Individualized decreasing-dose maintenance fluconazole regimen for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (ReCiDiF trial). Am J Obstet Gynecol 199(6): 613.e1-613.e9.

- Verma‐Gaur J, Traven A (2016) Post‐transcriptional gene regulation in the biology and virulence of Candida albicans. Cell Microbiol 18(6): 800-806.

- Brown AJP, Brown GD, Netea MG, Gow NAR (2014) Metabolism impacts upon Candida immunogenicity and pathogenicity at multiple levels. Trends Microbiol 22(11): 614-622.

- Pande K, Chen C, Noble SM (2013) Passage through the mammalian gut triggers a phenotypic switch that promotes Candida albicans Nat Genet 45(9): 1088-1091.

- Quintin J, Saeed S, Martens JHA, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Ifrim DC, et al. (2012) Candida albicans infection affords protection against reinfection via functional reprogramming of monocytes. Cell Host Microbe 12(2): 223-232.

- Cheng SC, Joosten LAB, Kullberg BJ, Netea MG (2012) Interplay between Candida albicans and the mammalian innate host defense. Infect Immun 80(4): 1304-1313.

- Ballou ER, Avelar GM, Childers DS, Mackie J, Bain JM, et al. (2016) Lactate signalling regulates fungal β-glucan masking and immune evasion. Nat Microbiol 2(2): 16238.

- Issi L, Farrer RA, Pastor K, Landry B, Delorey T, et al. (2017) Zinc cluster transcription factors alter virulence in candida albicans. Genetics 205(2): 559-576.

- Udayalaxmi D, Jacob S, D´Souza D (2014) Comparison between virulence factors of candida albicans and non-albicans species of candida isolated from genitourinary tract. J Clin Diagn Res 8(11):15-17.

- Khatib R, Johnson LB, Fakih MG, Riederer K, Briski L (2016) Current trends in candidemia and species distribution among adults: Candida glabrata surpasses albicans in diabetic patients and abdominal sources. Mycoses 59(12): 781-786.

- Cleary IA, Reinhard SM, Lazzell AL, Monteagudo C, Thomas DP, et al. (2016) Examination of the pathogenic potential of Candida albicans filamentous cells in an animal model of haematogenously disseminated candidiasis. FEMS Yeast Res 16(2): fow011.

- Tang S, Moyes D, Richardson J, Blagojevic M, Naglik J (2016) Epithelial discrimination of commensal and pathogenic Candida albicans. Oral Dis 22(1): 114-119.

- Gow NAR, Netea MG, Munro CA, Ferwerda G, Bates S, et al. (2007) Immune Recognition of Candida albicans β‐glucan by Dectin‐1. J Infect Dis 196(10): 1565-1571.

- Babula O, Lazdane G, Kroica J, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS (2003) Relation between recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, vaginal concentrations of mannose-binding lectin, and a mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphism in latvian women. Clin Infect Dis 37(5): 733-737.

- Ibrahim NH, Melake NA, Somily AM, Zakaria AS, Baddour MM, et al. (2015) The effect of antifungal combination on transcripts of a subset of drug-resistance genes in clinical isolates of Candida species induced biofilms. Saudi Pharm J 23(1): 55-66.

- Cowen LE, Sanglard D, Howard SJ, Rogers PD, Perlin DS (2015) Mechanisms of antifungal drug resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 5(7): a019752.

- Kanafani ZA, Perfect JR (2008) Resistance to antifungal agents: Mechanisms and clinical impact. Clin Infect Dis 46(1): 120-128.

- Morschhäuser J (2010) Regulation of multidrug resistance in pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet Biol 47(2): 94-106.

- Morio F, Loge C, Besse B, Hennequin C, Le Pape P (2010) Screening for amino acid substitutions in the Candida albicans Erg11 protein of azole-susceptible and azole-resistant clinical isolates: New substitutions and a review of the literature. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 66(4): 373-384.

- Teymuri M, Mamishi S, Pourakbari B, Mahmoudi S, Ashtiani MT, et al. (2015) Investigation of ERG11 gene expression among fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans: First report from an Iranian referral paediatric hospital. Br J Biomed Sci 72(1): 28-31.

- Strzelczyk JK, Slemp-Migiel A, Rother M, Gołąbek K, Wiczkowski A (2013) Nucleotide substitutions in the Candida albicans ERG11 gene of azole-susceptible and azole-resistant clinical isolates. Acta Biochim Pol 60(4): 547-552.

- Oliveira JMV, Oliver JC, Dias ALT, Padovan ACB, Caixeta ES, et al. (2021) Detection of ERG11 overexpression in candida albicans isolates from environmental sources and clinical isolates treated with inhibitory and subinhibitory concentrations of fluconazole. Mycoses 64(2): 220-227.

- Sardari A, Zarrinfar H, Mohammadi R (2019) Detection of ERG11 point mutations in Iranian fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans Curr Med Mycol 5(1): 7-14.

- Benedetti VP, Savi DC, Aluizio R, Adamoski D, Kava V, et al. (2019) ERG11 gene polymorphisms and susceptibility to fluconazole in Candida isolates from diabetic and kidney transplant patients. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 52: e20180473.

- Rosana Y, Yasmon A, Lestari DC (2015) Overexpression and mutation as a genetic mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans isolated from human immunodeficiency virus patients in Indonesia. J Med Microbiol 64(9): 1046-1052.

- Rojas AE, Pérez JE, Hernández JS, Zapata Y (2020) Quantitative analysis of the expression of fluconazole-resistant genes in strains of Candida albicans isolated from elderly people at their admission in an intensive care unit in Manizales, Colombia. Biomédica 40(1): 153-165.

- White TC (1997) Increased mRNA levels of ERG16, CDR, and MDR1 correlate with increases in azole resistance in Candida albicans isolates from a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41(7): 1482-1487.

- Feng W, Yang J, Yang L, Li Q, Zhu X, et al. (2017) Research of Mrr1, Cap1 and MDR1 in Candida albicans resistant to azole medications. Exp Ther Med 15(2): 1217-1224.

- Pam VK, Akpan JU, Oduyebo OO, Nwaokorie FO, Fowora MA, et al. (2012) Fluconazole susceptibility and ERG11 gene expression in vaginal candida species isolated from lagos Nigeria. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet 3(1): 84-90.

- Jombo GTA, Akpera MT, Hemba SM, Eyong KI (2010) Symptomatic vulvovaginal candidiasis: Knowledge, perceptions and treatment modalities among pregnant women of an urban settlement in West Africa. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol 12(1).

- Kumar A, Nair R, Kumar M, Banerjee A, Chakrabarti A, et al. (2020) Assessment of antifungal resistance and associated molecular mechanism in Candida albicans isolates from different cohorts of patients in North Indian state of Haryana. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 65(4): 747-754.

- Flowers SA, Colón B, Whaley SG, Schuler MA, Rogers PD (2015) Contribution of clinically derived mutations in ERG11 to azole resistance in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59(1): 450-460.

- Khandelwal NK, Chauhan N, Sarkar P, Esquivel BD, Coccetti P, et al. (2018) Azole resistance in a Candida albicans mutant lacking the ABC transporter CDR6/ROA1 depends on TOR signaling. J Biol Chem 293(2): 412-432.

- Lotfali E, Ghajari A, Kordbacheh P, Zaini F, Mirhendi H, et al. (2017) Regulation of ERG3, ERG6, and ERG11 Genes in antifungal-resistant isolates of Candida Iran Biomed J 21(4): 275-281.

- Vale-Silva LA, Coste AT, Ischer F, Parker JE, Kelly SL, et al. (2012) Azole resistance by loss of function of the sterol Δ 5,6 -Desaturase Gene (ERG3) in Candida albicans does not necessarily decrease virulence. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56(4): 1960-1968.

- Feng W, Yang J, Xi Z, Ji Y, Zhu X, et al. (2019) Regulatory Role of ERG3 and Efg1 in azoles-resistant strains of Candida albicans isolated from patients diagnosed with vulvovaginal candidiasis. Indian J Microbiol 59(4): 514-524.

- Fattouh N, Hdayed D, Geukgeuzian G, Tokajian S, Khalaf RA (2021) Molecular mechanism of fluconazole resistance and pathogenicity attributes of Lebanese Candida albicans hospital isolates. Fungal Genet Biol 153: 103575.

- Rodríguez-Leguizamón G, Ceballos-Garzón A, Suárez CF, Patarroyo MA, Parra-Giraldo CM (2020) Robust, comprehensive molecular, and phenotypical characterisation of atypical candida albicans clinical isolates from Bogotá, Colombia. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10: 57-147.

- Chen J, Hu N, Xu H, Liu Q, Yu X, et al. (2021) Molecular epidemiology, antifungal susceptibility, and virulence evaluation of candida isolates causing invasive infection in a tertiary care teaching Hospital. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11: 721439.

- Abbasi Nejat Z, Farahyar S, Falahati M, Ashrafi Khozani M, Hosseini AF, et al. (2018) Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility pattern of non-albicans candida species isolated from vulvovaginal candidiasis. Iran Biomed J 22(1): 33-41.

- Fornari G, Vicente VA, Gomes RR, Muro MD, Pinheiro RL, et al. (2016) Susceptibility and molecular characterization of candida species from patients with vulvovaginitis. Braz J Microbiol 47(2): 373-380.

- Gerstein AC, Berman J (2020) Candida albicans genetic background influences mean and heterogeneity of drug responses and genome stability during evolution in fluconazole. mSphere 5(3): e00480-20.

- Cernická J, Šubík J (2006) Resistance mechanisms in fluconazole-resistant candida albicans isolates from vaginal candidiasis. Int J Antimicrob Agents 27(5): 403-408.

© 2025 Sebastián Atehortua Giraldo. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)