- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography

First Record of the Globally Endangered Whale Shark (Rhincodon Typus Smith, 1828) in the Mediterranean Waters of the Gaza Strip, Palestine, and Its Consumption Shortly After the Ceasefire Following the Two-Year Israeli War of Genocide (2023-2025)

Abdel Fattah N Abd Rabou*1, Elham I Abu Aitah1, Sawsan K Samara, Marwa S Alajrami1, Majed A Jebril2, Zuhair W Dardona2, Ibrahim A Abu Harbid3, Jehad Y Salah4, Sameeh M Awadalah4, Wajdi M Saqallah4, Mohammed A Aboutair4, Othman A Abd Rabou5, Ola A Abd Rabou6, Huda E Abu Amra7, Asmaa A Abd Rabou8, Randa N Alfarra9, Doaa F Abd Rabou9, Samira N Yousif10, Hala R Al-Harazeen11, Hashem A Madkour12, Fatma A Madkour13, Fatma Abdelhakeem13, Rola I Jadallah14, Faten A Al-Hamidi15, Norman A Khalaf16, Mohammed R Al-Agha17

1Department of Biology and Biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine

2Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Medical Sciences, Israa University, Gaza Strip, Palestine

3Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Faculty of Medical Laboratory Sciences, Al-Azhar University, Gaza Strip, Palestine

4General Directorate of Fisheries, Ministry of Agriculture, Gaza Strip, Palestine

5Department of Journalism and Media, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine

6Department of Smart Systems Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine

7Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Al-Aqsa University, Gaza Strip, Palestine

8Department of Civil Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine

9Department of Curricula and Teaching Methods, Faculty of Education, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine

10Department of Biology and its Teaching Methods, Faculty of Education, Al-Aqsa University, Gaza Strip, Palestine

11Department of Geography, Faculty of Arts, Al-Aqsa University, Gaza Strip, Palestine

12Department of Marine and Environmental Geology, National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Hurghada, Egypt

13Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, South Valley University. Qena, Egypt

14Department of Biology and Biotechnology, Arab American University, Jenin, West Bank, Palestine

15Department of Media & Communication Technology, University College of Applied Sciences, Gaza Strip, Palestine

16Department of Environmental Research and Media, National Research Center, University of Palestine, Gaza Strip, Palestine

17Department of Marine Sciences, Faculty of Science, Islamic University of Gaza, Gaza Strip, Palestine

*Corresponding author: Abdel Fattah N Abd Rabou, Department of Biology and Biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Islamic University of Gaza, PO. Box 108, Gaza Strip, Palestine

Submission: December 08,2025;Published: January 09, 2026

ISSN 2578-031X Volume 8 Issue 1

Abstract

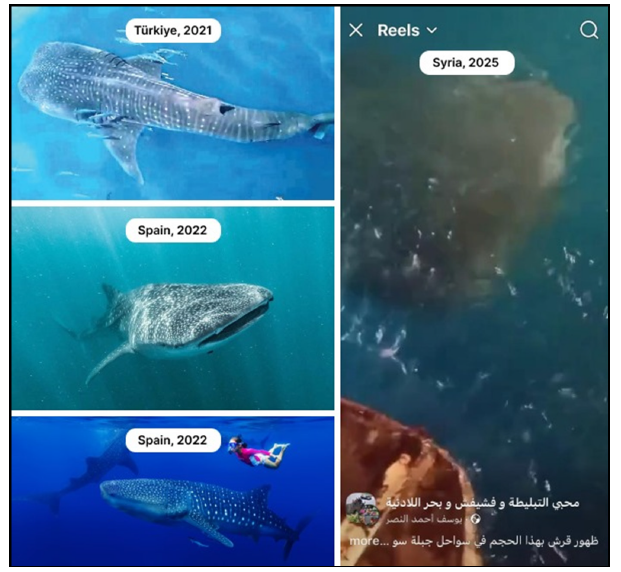

The Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus Smith 1828), the largest cartilaginous fish and the third largest living creature in the world, is widely distributed in the tropical and subtropical waters of the world’s oceans. On October 17, 2025, a Whale Shark was sighted and caught off the coast of Khan Younis in the Mediterranean Sea, southern Gaza Strip, Palestine. This study investigates the incident of sighting, catching, and consuming a Whale Shark specimen by starving Gazan fishermen and displaced people in Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, on October 17, 2025. The current descriptive study relied on collecting data and images related to the first documented Whale Shark in the Mediterranean Sea off Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Palestine, through monitoring news sites and social media platforms. Discussions and consultations were also held with various stakeholders, including fishermen who caught this massive creature and displaced people who consumed its meat. Several local sources claimed that the Gazan Whale Shark was between 7 and 8 meters long and weighed about 2.3 tons, and that its meat was consumed by 3,000 to 4,000 Gazans, most of whom were displaced people forced to leave their homes due to the Israeli war of genocide (2023-2025). This rare incident represented the fourth sighting of this creature in the Mediterranean Sea, following sightings in Türkiye in 2021, Spain in 2022, and Syria in 2025. It is strongly believed that this species was a Lessepsian migrant. Many media outlets and social media platforms covered the incident of Whale Shark capture and its exploitation by the starving Gazans shortly after the Israeli war of genocide (2023-2025). In contrast, most tweeters considered the Whale Shark in question a blessing from heaven bestowed by the Mediterranean Sea upon the oppressed Gazans, victims of the blatant and ongoing crimes of the Israeli occupation.

Keywords:Whale Shark; Rhincodon typus; Globally endangered; First record; Mediterranean Sea; Lessepsian migrant; Capture; Consumption; Starving and displaced Gazans; Israeli war of genocide (2023-2025). Gaza Strip; Palestine

Introduction

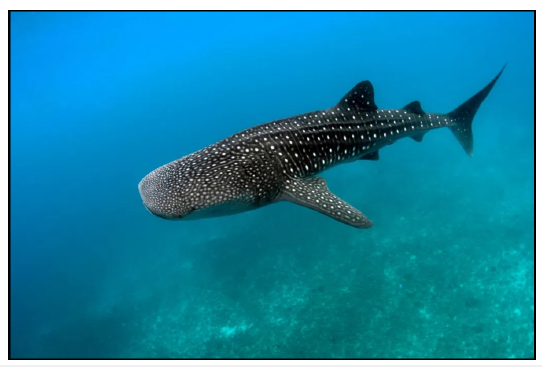

Whale Sharks (Rhincodon typus Smith 1828), the largest fish worldwide (Figure 1), are broadly distributed throughout tropical and sub-tropical waters of the world’s oceans [1,2]. The Whale Shark gets its name from its ability to grow to the size of some whale species. It also feeds by filtering, much like baleen whales. Whale Sharks can reach lengths of 14 meters or more and live for more than a century, between 80 and 130 years [3,4]. They, as filter feeders, are thought to feed mainly on zooplankton, krill, small schooling fishes, fish eggs, cephalopods, and other nektonic prey [5-8]. They are generally solitary but are occasionally observed in groups or schools, both in coastal and oceanic waters, when food is plentiful [2,9,10]. These majestic creatures are known to be highly migratory, traveling great distances to feed and breed. With their very large mouths, Whale Sharks share the Megamouth Shark (Megachasma pelagios Taylor, Compagno & Struhsaker, 1983) and the Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus Gunnerus, 1765) their feeding habits as filter feeders. They are generally considered peaceful species and pose no threat to humans. However, they are currently threatened by targeted fishing, bycatch, collisions with large vessels (ship strikes), pollution, and the effects of climate change [11-14].

Figure 1:The globally endangered Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus Smith, 1828) is the largest fish in the world (Source: [24]).

In fact, they are being overexploited in many Southeast Asian countries [15]. It is important to note that the Whale Shark possesses important biological characteristics. such as large size, slow growth, late maturity and longevity, which may limit its recruitment and make it particularly vulnerable to exploitation in some parts of the world, and its numbers may be slow to recover from any overexploitation [16]. Consequently, the species is currently listed as Endangered (its numbers are declining) by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), red list of threatened species [17]. The tropicalization of Mediterranean waters accelerates the establishment of tropical fish species in the region [18]. Invasive organisms may invade the Mediterranean Sea via several routes, including the Suez Canal, which opened in 1869 to connect the Red Sea to the Mediterranean [19-21]. The Strait of Gibraltar, which connects the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Ocean, is another entry point [22]. Lessepsian migration is a term describing the movement of some marine organisms from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal. This phenomenon is responsible for the significant changes in fish communities occurring in the Mediterranean, especially in its eastern part [23,24].

Whale Sharks are known to be found in the Red Sea [17,25-31] and can therefore sneak into the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal. In their most recent reference list of elasmobranchs found in the Mediterranean, Serena et al. [32] did not mention the presence of Whale Sharks in the region. Since 2021, very rare records of Whale Sharks have been reported in the Mediterranean Sea. On October 18, 2021, a Whale Shark was sighted off the coast of Samandağ (Hatay city, Türkiye, northeast Mediterranean Sea), by a commercial longliner [33]. Another sight was confirmed in the Spanish coast or the North African coast near Ceuta by a video of the creature that was shared with new site LA Vanguardia who published it on Saturday, December 10, 2022 [4]. The third appearance of a Whale Shark in the Mediterranean Sea was off the coasts of Latakia and Jableh in Syria, after it collided at night with a six-meter-long fishing boat, as documented by Syrian media [34-37]. There are no other records of Whale Shark sightings or observations in the mediterranean waters. It is estimated that more than 30 species of cartilaginous fish (class Chondrichthyes), including sharks, are present in the marine ecosystem of the Gaza Strip, and many of them are caught for human consumption [38-41]. This is evident from any visit by a Palestinian or foreign visitor to the fish markets located in certain places along the coast or in public markets. No studies or reports have mentioned sightings or observations of Whale Sharks in the Mediterranean waters off the Gaza Strip. They are, in fact, an invasive, giant, and extremely rare species. Globally, numerous studies have been conducted investigating biology, ecology, behavior, and other aspects related to Whale Sharks [42-57].

On Friday, October 17, 2025, Gazan fishermen caught a large Whale Shark off the coast of Khan Younis in the southern Gaza Strip [58]. They hauled it ashore using thick ropes, likely for consumption. This study aims to document the first recorded sighting of a Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus Smith 1828) in the Mediterranean Sea off the coast of the Gaza Strip on October 17, 2025, and to document its capture and consumption by starving Gazans who gathered around it shortly after the ceasefire that followed the two-year genocidal war (2023-2025) waged by the Israeli occupation on the Gaza Strip on October 7, 2023. The importance of this study lies in the fact that it is the first of its kind to examine the first record of a Whale Shark, the largest fish in the world, in the Palestinian marine ecosystem.

Methodology

The current descriptive study relied on collecting data and photos related to the first documentation of a Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus Smith 1828) in the Mediterranean Sea off Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip. This was accomplished by monitoring news websites and social media platforms to cover all aspects of this extremely rare event in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Contacts and discussions were also held with various stakeholders, such as the General Directorate of Fisheries at the Ministry of Agriculture, the fishermen who caught this huge creature, and some displaced Gazans who cooked and ate its meat. The Gaza Strip (Figure 2) is an arid to semi-arid strip of Palestinian territory located in the southeastern Mediterranean Sea. It is 42km long and covers an area of 365km². Its current population exceeds 2.4 million, making the Gaza Strip one of the most densely populated areas in the world. Since October 7, 2023, the Israeli occupation forces have been waging a brutal war, which international observers, legal experts and political analysts have described as a war of genocide and ethnic cleansing on the Gaza Strip. During this war, the Israeli military has killed more than 80,000 of Gazans, wounded more than 180,000, and repeatedly displaced nearly 90% of the population. Most of the population is suffering from a deliberate famine imposed by the Israeli occupation during its painful war on the Gaza Strip, forcing Gazans to seek any form of food they can obtain, including terrestrial wildlife (mammals and birds) or marine animals such as sea turtles, dolphins, rays, and sharks including the globally endangered Whale Shark, which appeared for the first time in October 17, 2025 in the Mediterranean waters of the Gaza Strip, Palestine.

Figure 2:A map showing the geographic allocation of Palestine and the Gaza Strip.

Result

The first record of the Whale Shark in the Gaza Strip

The Whale Shark (Rhincodon typus Smith 1828), caught by fishermen off the coast of Khan Younis, south of the Gaza Strip, on October 17, 2025, is significant because it adds to the new and first-of-its-kind record of this rare, unique, and massive creature in Palestinian Mediterranean waters. It was caught by fishermen and pulled to the shore of Khan Younis with ropes. It did not wash ashore as many media outlets reported. This species is a migratory and invasive species, believed to have come from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean via the Egyptian Suez Canal, in what is scientifically known as the Lessepsian migration. Its importance is also evident in the fact that it is the largest cartilaginous fish in the world, and its presence on the Mediterranean coasts has only been recorded in Türkiye in 2021, southern Spain in 2022, and Syria in 2025. It is a momentous event that the marine waters of the occupied Gaza Strip welcomed this wonderful, unique, beautiful, gentle, and peaceful creature, despite the circumstances of its capture and the distribution of its meat to be cooked among the displaced from various areas of the Gaza Strip to Khan Younis. It is not easy for Gazans to forget this momentous event, in which a Whale Shark came to break the Israeli blockade imposed on the patient Gazans for 18 years.

The story of Whale Shark hunting in the Gaza Strip

On Friday, October 17, 2025, Gazan fishermen caught a giant, live Whale Shark about 700 meters off the coast of Khan Younis, south of the Gaza Strip. The researchers contacted with the fishermen who caught the fish. They confirmed that the shark was entangled in a fishing net targeting the invasive, Black-barred Halfbeak (Hemiramphus far Forsskål, 1775), which belongs to the family Hemiramphidae. The net was initially set up 400 meters from the shore, but the whale became entangled in it, causing it to be pulled westward by the force of the fish, until it was 700 meters from the shore. The capture and control of the Whale Shark using thick ropes resulted in the net tearing, necessitating the use of another large net, called a Shanshula net, used for sardines. The nets were brought in by Gazan fishermen using between 20 and 30 small fishing boats called rowing or paddle boats (Hasakas with oars) (Figure 3), which do not run on engines, as the Israeli occupation prohibited the use of motorized fishing boats during its brutal war on the Gaza Strip. The number of fishermen involved in the Whale Shark hunt was estimated to be in the dozens. The operation lasted about an hour and a half, from 11:00 AM to 12:30PM. The captured specimen was eventually dragged to the seashore near the fishing port in Khan Younis, in the southern Gaza Strip. The Whale Shark died 200 meters from the shore during the process of being pulled by a crowd of fishermen, which made it easier for it to reach the shore.

Figure 3:The non-motorized hasaka (oar-drawn hasaka) is the most common fishing boat used by fishermen in the Mediterranean ecosystem of the Gaza Strip.

Large Gazan crowds inspecting and butchering the Whale Shark

As soon as the fishermen pulled the Whale Shark ashore near the khan Younis fishing port, hundreds of Gazans, especially those displaced by the Israeli genocidal war, gathered around to see the strange creature, unlike anything they had ever seen before (Figure 4). The onlookers were amazed by the shark’s length, size, and unusual appearance. They celebrated a rare and valuable catch. According to videos posted on various news sites and social media platforms, many Gazans mistakenly considered it a “huge whale” or a “strange sea creature”, while others simply described it as a “rare and precious treasure” or a “unique blessing from God Almighty to the afflicted Gazans”. After examining it, fishermen and other Gazans, most of them were displaced and starving, began butchering the Whale Shark for food (Figure 4). Its meat was sometimes sold on the beach to those who couldn’t reach it, at affordable prices ranging from ten to twenty Israeli shekels (the local currency) per kilogram, equivalent to three to six US dollars per kilogram. After the Whale Shark was slaughtered and its meat distributed, Gazans described it as having vanished without a trace. The Whale Shark meat was prepared in various ways, including boiling, frying, and grilling. Discussions with various stakeholders revealed that up to 3,000 to 4,000 Gazans consumed the meat of the shark. Opinions varied in its taste, ranging from praise to criticism, due to its high fat content. Nevertheless, it was a precious opportunity for Gazans to witness this rare shark in the Mediterranean. Had it not been for the fatal famine imposed by the Israeli occupation on Gazans, who were suffering from protein deficiency, during its war, the shark’s fate would have been much better.

Figure 4:Hundreds of Gazans, starved by the Israeli occupation during its genocidal war in the Gaza Strip (2023- 2025), gather around a giant Whale Shark to cut its flesh for later consumption.

The experience of a Gazan woman cooking and consuming Whale Shark meat

Field data collected from interviews with families who obtained

Whale Shark parts showed that access to meat was linked to the

availability of appropriate tools. Participants indicated that those

who used sharp knives and were accompanied by others to collect

the meat were able to obtain larger quantities (Figure 5). One family

obtained approximately 13 kilograms of meat and liver; a significant

amount compared to other families who obtained much less. One

woman reported that the amount of meat decreased considerably

after cooking; what used to fill a large container now filled a smaller

one. Sensory observations from family members included:

a. The white meat of the Whale Shark was characterized

by its tender, easy-to-chewy texture and delicious flavor,

distinguishing it from the fish commonly found in the local

market.

b. The liver was highly rated for its flavor and texture, described

as rich and like poultry liver with a more concentrated taste.

c. The fin meat was characterized by its high fat content, reddish

color, and the presence of cartilage lines, making it more

difficult to chew.

Figure 5:Efforts by Gazans to obtain the meat of a Whale Shark that was accidentally caught at sea and dragged to the shore of Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, on October 17, 2025.

?Islamic ruling on eating shark meat

All sea animals that live only in water are permissible (halal) to eat, both the living and the dead, due to the general statement of God Almighty: “Lawful to you is the game of the sea and its food as provision for yourselves and for travelers, but forbidden to you is the game of the land as long as you are in a state of ihram. And fear Allah, to whom you will be gathered” [Al-Ma’idah: 96]. The Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) said regarding the sea: “Its water is pure and its dead are permissible”. The scholars said: “The basic principle regarding sea animals that typically live only in water is that they are permissible (halal)”. About shark meat is permissible (halal) due to the general statement of the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him): “Two types of dead animals and two types of blood have been made lawful for you: The two types of dead animals are fish and locusts, and the two types of blood are the liver and the spleen”. The fact that sharks are predators does not preclude this; the ban on all predators with fangs applies only to terrestrial predators, not marine predators.

Spatial description of the Gazan Whale Shark specimen

Whale Sharks are the largest sharks, and indeed the largest fish alive today. Discussions with the Gazan fishermen who caught the Whale Shark, followed by an examination of subsequent videos and photographs, revealed that the Whale Shark specimen measured between seven and eight meters in length, not ten meters as widely reported on news sites and social media platforms. Experienced fishermen estimated the weight of the specimen to 2.3 tons. The specimen is characterized by a broad, flat head, a large, wide mouth, and small eyes. The mouth is located at the front of the head, unlike other sharks commonly caught by local fishermen. There are five large gill slits on each side of the head region, just above the pectoral fins. The skin on the upper side is dark gray and rough, having pale or light-colored spots, while the belly is white. In fact, this giant creature is easily recognizable among other giant marine creatures by its distinctive features of light spots and prominent ridges (lines or stripes) on its dorsal skin. Regarding the fins, the animal has several single medial fins and paired lateral fins. The middle fins consist of two dorsal fins located relatively late in the body, with the first dorsal fin being much larger than the second, one anal fin, and a caudal fin with two asymmetrical lobes; the upper lobe is larger than the lower lobe. As with other fish, the lateral fins consist of a pair of pectoral fins and a pair of pelvic fins.

Media coverage of Whale Shark hunting and consumption

Numerous local, Israeli, regional, and international media

outlets covered the incident of Whale Shark hunting and

consumption by starving Gazans during the Israeli war of genocide

(2023-2025). Israeli headlines were far from fair, portraying Gazans

as reckless and environmentally unsound. Some of these headlines

are listed below:

a) The Whale Shark: The giant of the seas that amazed the shores

of Gaza.

b) Starving Gazans butchered stranded Whale Sharks amid

crippling food shortages.

c) Palestinians film remains of endangered Whale Shark dragged

by ropes on Gaza shores.

d) A feast from heaven: Gaza fish ignites social media amid

popular joy and Israeli anger.

e) Rare Whale Shark, a symbol of wonder for Israelis, killed and

butchered in Gaza.

f) A sea monster caught in Gaza’s net: A giant Whale Shark is

enough to feed 14,000 people.

g) Israel’s foreign ministry denounces video allegedly showing

Gazans catching Whale Shark.

h) Israeli propagandists exploit Whale Shark’s presence in Gaza

to demonize residents.

i) Whale Shark killed savagely by Gazans off Gaza coast sparks

outrage.

j) Gazans ‘horrifically’ kill rare Whale Shark dragged from ocean.

k) Shark spotted and watched by Israelis heads to Gaza-and gets

butchered for meat.

l) Whale Shark that captivated Israelis found dead after being

caught in Gaza.

m) Getting tired of eating Nutella, the peaceful Palestinians killed

an endangered Whale Shark that was swimming off the coast

of Khan Younis in the south of Gaza. An endangered species on

the IUCN list, yet they have nothing better to do than destroy

life. Pathetic.

Social media coverage of Whale Shark hunting and consumption

Social media platforms witnessed heated and humorous

reactions to the incident of a Whale Shark being caught and eaten

by the starving Gazans, a consequence of the Israeli occupation.

Most tweeters considered the Whale Shark a blessing from heaven,

bestowed by the sea upon the oppressed Gazans. Below are some of

these tweets and comments:

a) Strange or not, it will be eaten, people are craving meat.

b) “This is our provision, and it will never run out”.

c) “He fed them when they were hungry and gave them security

when they were afraid”. All praise is due to You, O Lord.

d) God, feed our people and brothers in Gaza from hunger and

protect them from fear.

e) Thank God, most of the displaced people on the Khan Younis

beach ate some of its meat.

f) Whale Shark: First documented sighting and first consumption

of its kind in the Gaza Strip.

g) The Israelis are the ones who let the Gazans starve, then blame

them for catching a fish?

h) The Whale Sharks is a blessing from God for Gazans, amid the

ongoing siege and hunger.

i) Gaza is blessed with giant shark whales.

j) Whale Shark: A gift from the sea to the people of Gaza.

k) Israel accuses Gazans of cruelty for catching a shark!

l) Israel, which claims to protect nature, is the biggest destroyer

of the nature and environment of the Gaza Strip, and then it

claims to sympathize with the Whale Shark. What a disgrace!

Discussion

Whale Sharks (Rhincodon typus Smith 1828) are widespread in tropical and subtropical waters of the world’s oceans and seas, including the Red Sea, which connects to the Mediterranean Sea via the Egyptian Suez Canal. Whale Sharks were not recorded in the Mediterranean Sea before 2021, but for some reason, three specimens of this giant fish were recorded in the coastal waters of Türkiye (2021), Spain (2022), and Syria (2025) respectively (Figure 6). According to Sequeira et al. [59], the anticipated changes in sea surface temperature have led to a slight shift in suitable habitats towards the poles, which may increase the likelihood of more Whale Sharks in the Mediterranean in the future. In a colder environment, Turnbull and Randell [60] recorded a rare Whale Shark sighting in the Bay of Fundy, Canada, and demonstrated that Whale Sharks might be able to tolerate the cold waters of this bay, although they were not subsequently sighted there. A single Whale Shark was recently recorded along the Palestinian coastal waters of the Mediterranean Sea, stretching from Haifa in the north to the Gaza Strip in the south. This is the fourth time this giant and very rare fish has been recorded in the Mediterranean Sea, following sightings in Türkiye, Spain and Syria. Generally, the natural habitat of Whale Sharks, as previously mentioned, is the warm tropical oceans, not the shallow seas of most of the Mediterranean.

Figure 6:Three separate specimens of Whale Sharks of varying lengths were spotted on the Mediterranean coasts of Türkiye (2021), Spain (2022) and Syria (2025).

Therefore, Whale Shark sightings in the Mediterranean are more likely due to them being strays or occasional visitors, rather than a settled population. This rare occurrence in the Mediterranean environment may be attributed to unusual ocean currents, changes in water temperature, or irregular, prolonged migrations. Given the extreme rarity of Whale Sharks in the Mediterranean, each new sighting attracts the attention of marine biologists and ecologists. Indeed, these important records highlight the dynamic nature of marine ecosystems and demonstrate that large ocean-dwelling species sometimes venture into unexpected places. Despite what happened to the Whale Shark that was caught and then eaten by the starving Gazans amidst the war of genocide, ethnic cleansing and the weapon of starvation used by the Israeli occupation in the Gaza Strip, it is a great opportunity for the Gazans and the scientific community to witness, on the ground or through the media and social media platforms, this great creature that is classified globally as the largest fish in the world, and the third largest creature after the Blue Whale (Balaenoptera musculus Linnaeus, 1758) and the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758) [61,62]. The Whale Shark has never been listed among the cartilaginous fish that live or are found in the Mediterranean Sea [32,63,64], so the new records for this species in the coasts of Türkiye, Spain, Syria and Palestine in the Mediterranean Sea represent a new addition.

Since 50 species of sharks live in the Mediterranean Sea [65], the addition of the Whale Shark raises the total number of shark species in this sea to 51, although the Mediterranean is not a typical habitat for this species. Before the Whale Shark reached the Mediterranean coastal waters of the Gaza Strip, Israeli media sources indicated that the same fish had been seen along the Palestinian Mediterranean coastal waters extending from north to south [66-68]. The only logical explanation for this stray specimen of Whale Sharks reaching the Palestinian Mediterranean waters is that it infiltrated from the Red Sea into the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal as a Lessepsian migrant. Similarly, Turan et al. [33] confirmed that the Whale Shark seen off the coast of Samandaǧ (Hatay City, Türkiye, Northeast Mediterranean) on October 18, 2021, had arrived in the area via the Suez Canal. The same scenario is strongly suggested for the Whale Shark that appeared off the coast of Syria in July 2025. In contrast to the mechanism of arrival, Spanish news sources indicated that the Whale Shark specimen seen in December 2022 off the coast of Spain traveled to the western Mediterranean via the Strait of Gibraltar [4].

Although the Whale Shark can exceed 14 meters in length and can sometimes reach 18 meters, the specimen caught in the Gaza Strip measured 7 to 8 meters in length, according to the estimates of the fishermen who caught and butchered it. This length means that the Whale Shark specimen was relatively small and got lost in the Red Sea, passing through the Suez Canal and then into the eastern Mediterranean. Although it was recorded off the continental coast of Portugal in the Atlantic Ocean and not in the Mediterranean Sea, the Whale Shark specimen measured between 7 and 8 meters in length [69], which is very similar to the length of the Gazan shark specimen. According to Turan et al. [33], a fisherman estimated the length of the Whale Shark specimen seen in Türkiye in October 2021 to be about three meters, which means it is relatively small compared to the shark specimen seen off the coast of Spain in December 2022, which was estimated to be about 10 to 12 meters long [70]. The specimen spotted off the Syrian coast (https:// www.facebook.com/reel/599646606511510) reached a size of 10 meters, according to estimates by officials and fishermen [35,36].

The transfer of relatively small and very rare specimens of Whale Sharks from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean Sea via the Suez Canal can be attributed to their relatively large numbers in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Tadjoura in Djibouti, as several studies have shown [17,25,27-31,36]. In fact, the migration of Whale Sharks thousands of miles from the Red Sea to the Mediterranean, although rare, may be attributed to their search for food, as their movement depends mainly on the availability of plankton. The journey to the Mediterranean Sea may represent part of the migration movements of these fish, allowing them to reach new feeding areas during certain times of the year. Since Whale Sharks are generally found in all temperate and tropical waters worldwide [71,72], their migration from the Red Sea to the warmer eastern Mediterranean via the Suez Canal may be attributed to climate change, although this possibility has not yet been definitively confirmed.

Whale Sharks face a threat when they become entangled in fishing gear or debris. These fish may become entangled in nets, ropes, or other marine debris, causing debilitating injuries, slowed movement, disrupted feeding, and potentially death. Although the Gazan Whale Shark specimen was entangled in a fishing net targeting the Black-barred Halfbeak, many authors have cited numerous fishing gear and marine debris for such entanglements. A marine diver helped free a swimming Whale Shark after a rope became entangled around its body off the coast of Mexico [73]. In Spain’s Ceuta, scuba divers, working together for nearly five hours, successfully released a Whale Shark that had been caught in a traditional fishing net used in southern Spain and North Africa to catch Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus thynnus Linnaeus, 1758) and Swordfish (Xiphias gladius Linnaeus, 1758) [70]. Similarly, Whale Sharks were occasionally encircled in tropical tuna purse-seine nets as pointed out by Escalle et al. [74]. On the coast of continental Portugal, a Whale Shark was found alive and in good condition inside a set-net, where divers were able to free it and return it to the ocean. In fact, entanglement with fishing gear or marine debris is a phenomenon that threatens many globally endangered species such as baleen whales, dolphins, sharks, sea turtles and others, both locally and globally [39,40,75-79]. The seven- to eight-meter-long Whale Shark was not the first local record of a rare or giant marine creature in the Gaza Strip. Over the past few years, the Gaza Strip coast has witnessed first and rare sightings of other marine animals, such as the Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus Herman, 1779) in 2023 [80,81], and the Striped Dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba Meyen, 1833) in 2025 [82]. Over the past forty years, live and dead specimens of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus Linnaeus, 1758), Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus Montagu, 1821), and Short-beaked Common Dolphins (Delphinus delphis Linnaeus, 1758) have been observed on the coast of the Gaza Strip [83,84]. Regarding the worldwide critically endangered to vulnerable Sea turtles, Abd Rabou [40,41,79] reported occurrence, strandings and accidental consumption of three species of these sea turtles in the marine ecosystem of the Gaza Strip: Loggerhead Sea turtles (Caretta caretta Linnaeus, 1758), Green Sea turtles (Chelonia mydas Linnaeus, 1758), and Leatherback Sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea Vandelli, 1761). The latter is considered the largest of the seven known species of sea turtles in the world’s seas and oceans [62,85].

Human threats have led to a dramatic decline in Whale Shark populations [86,87]. Indeed, Whale Sharks have become a target of commercial fisheries, or at least valuable by catch in various parts of the world. They are highly valued in global markets, particularly in Asia, where the demand for their meat, fins, liver, and oil threatens their survival [12,88-90]. For example, in Indonesia, artisanal fishermen catch Whale Sharks and then butcher them, and their meat and oil are sold along the coasts of its islands [91,92]. Given that Whale Sharks are consumed in many countries worldwide, as the studies have shown, why did some dissenting voices exaggerate the capture and consumption of a Whale Shark specimen in the Gaza Strip on October 17, 2025? Gazans are not enemies of the environment, as the Israeli occupiers of Palestine portray them; on the contrary, they are committed to its preservation, especially the protection of endangered species. Many Gazans released various species of sea turtles to the sea as reported by Abd Rabou [40,41,79]. Even the Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus Herman, 1779), which was spotted off the coast of the southern Gaza Strip in May 2023, had prompted several appeals from local authorities to Gazan fishermen months before the October 7, 2023 war, urging them not to harm this rare marine mammal and to protect it by all possible means [80].

In fact, the conditions of the two-year Israeli war of genocide (2023-2025), coupled with the crippling blockade, deliberate starvation, protein shortages, and the spread of diseases and epidemics, drove most Gazans to seek any source of food, even endangered animals, including the Whale Shark in question [24]. Whale Shark meat was distributed to approximately 3,000-4,000 displaced Gazans who suffered and continue to suffer from severe protein deficiency and the complications resulting from this glaring deficiency, so that they could cook and eat it. As the famous saying goes, “Hunger is a disbeliever,” and during the genocidal war and ethnic cleansing waged by the Israeli occupation on the Gaza Strip, Gazans resorted to eating foods they had never dreamed of eating. In Islamic law, many Gazans believe that there are no Quranic verse or hadith that prohibits eating shark meat, especially that of the Whale Shark mentioned, and therefore they consider eating shark meat and other cartilaginous fish permissible (Halal). The four major Sunni schools (Madhabs) of thought agree that eating all types of fish is undoubtedly permissible, as this is explicitly stated in the Qur’an and Sunnah [93].

Indeed, Gazans are aware of many marine creatures that should be protected and preserved, as evidenced by the fact that before the Israeli war, fishermen would return sea turtles by-caught in their nets to the sea [40,41]. The reasons that prompted Gazans to eat the single Whale Shark-the first such specimen ever recorded on the beach of the Gaza Strip-are many and varied. A poor, hungry person with no food to eat cannot be advised not to hunt terrestrial or marine biota for food. Most of the Gazans suffered from hunger and deprivation of animal and fish proteins during the Israeli war. Indeed, protein is an essential nutrient that plays a vital role in maintaining health and supporting various bodily functions. It serves as the building block for tissues, organs and cells and is necessary for growth, repair, and maintenance. Protein also supports the immune system, transports nutrients, and can be used as an energy source [94-96]. Therefore, Israel’s actions during the war, including the closure of crossings and the tightening of the blockade, the destruction of the fisheries and livestock sectors, including poultry farms, and the destruction of farms and their crops, all contribute to depriving people of protein and other organic and inorganic nutrients necessary for building a healthy body. In this context, several international and humanitarian organizations have warned of the impact of these Israeli actions on the next Palestinian generations and their suffering from serious health problems. Newspapers and humanitarian organizations constantly discuss the dangers of famine, defined as a severe food shortage leading to malnutrition, starvation, and ultimately death. Hundreds of lives, especially infants and children, have been lost in the Gaza Strip due to this famine and the scarcity of medicine (Personal Communications).

This fact was confirmed by Kiros & Hogan [97] who pointed out that exposure to famine, war and environmental degradation in Ethiopia, as in the Gaza Strip, has negative impacts on infants and child mortality. The capture and consumption of a single Whale Shark in the Gaza Strip’s marine ecosystem does not pose a clear threat, as the Mediterranean Sea is not yet a habitat for this species, unlike the Red Sea and tropical oceans. The same Whale Shark was sighted several times over a period of weeks in September and October 2025 along the northern and central Palestinian Mediterranean coast, including off the coasts of Haifa, Netanya (Umm Khalid), Jaffa (Yafa), Ashdod (Asdud), and Ashkelon (Asqalān or Al-Majdal), according to previously mentioned Israeli media outlets [66-68]. According to Pierce and Norman [13], the Whale Shark is a globally threatened species due to overfishing, bycatch, ship collisions, and Whale Shark tourism, which can disrupt its feeding habits and cause injuries from tourist boat propellers. Furthermore, Whale Sharks are highly valued in global markets, and the demand for their meat, fins, and oil remains a threat [87].

Although this is the only incident of catching and eating a Whale Shark in the Gaza Strip, and no consumption of it has been recorded in other Mediterranean countries due to the extreme rarity of this huge creature that infiltrates the Mediterranean environment either through the Suez Canal in the eastern Mediterranean or through the Strait of Gibraltar in the west, it has spread like wildfire through the media and social media platforms. Some of these media outlets, particularly Israeli ones, focused on the incident, ignoring or downplaying the underlying causes. Israeli media reported that while Israelis protect baleen whales, dolphins, sea turtles, and cartilaginous fish and prohibit hunting or harming them, Palestinians hunt and eat these endangered creatures. But the stark reality, highlighted here, is that before the two-year Israeli offensive (2023-2025), Palestinian fishermen were releasing dolphins, and even some sea turtles, back into the sea after they became accidentally entangled in their fishing gear. But the severe scarcity of necessities for Gazans caused by the war, the tightening of the siege, and the impending famine left Gazans with no choice but to resort to hunting these endangered marine creatures (and other terrestrial creatures, whether endangered or not) as a source of food (Personal Observations and Communications). In fact, most local opinions regarding the fishing of the Whale Shark in the waters off the Gaza Strip and the distribution and consumption of its meat by starving Gazans agreed that the Whale Shark specimen was a gift from heaven considering the famine deliberately imposed by the Israeli occupation and ignored by the world. Based on the foregoing and given the deplorable conditions endured by Gazans under the unprecedented Israeli war of genocide and ethnic cleansing, and its aftermath, Gazans have the right to hunt and consume whatever they find from the bounty of the land and sea (even if it is threatened), for human life is paramount.

The contradictory voices in Israel, and perhaps others, must cease their illogical pronouncements and rhetoric about protecting and caring for terrestrial and marine animals (under false humanitarian slogans) while the Palestinians are being exterminated before the eyes and ears of a world that remains unmoved. If Palestinians (especially Gazans) lived in prosperity, they would not resort to violating the environment and consuming its threatened resources. The nations of the world, and international and humanitarian organizations, must prioritize halting the crimes perpetrated by the Israeli occupation with full force in the Gaza Strip (and the West Bank), instead of burdening the Gazans with accusations of environmental corruption. Despite the biased Israeli propaganda against the Gazans, it is truly beautiful and heartening to review the news sites and social media platforms related to the hunting and consumption of a Whale Shark specimen by the hungry and oppressed Gazans, to find that most of them (except for the Israeli sites, of course) support the Gazans because they are aware of their miserable reality in light of the Israeli war of extermination and ethnic cleansing and the Israeli entity’s disregard for the decisions of international courts and global appeals. For example, an Israeli website claims that “peaceful Palestinians, tired of eating Nutella, killed an endangered Whale Shark swimming off the coast of Khan Younis in southern Gaza. This species is listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), yet all they seem to do is destroy life. It’s a tragedy”. It’s worth noting that although the Israeli war has only partially ended since October 10, 2025, necessities for Gazan population remain extremely scarce and prohibitively expensive, making them unaffordable.

As a result, the famine hasn’t ended; it has been disastrously managed. The supposed widespread availability of Nutella, despite its astronomical price, along with some chocolate, biscuits, vegetables, fruits, and frozen meat, doesn’t meet the needs of even 10% of the population. Thus, the famine continues under dubious international covers. Israeli propaganda prompted some Facebook activists to say: “Israel, which claims to protect nature, is the biggest destroyer of the nature and environment of the Gaza Strip and then claims to sympathize with the Whale Shark. What a disgrace!”. In conclusion, the news headlines and social media posts, in both Arabic and English, are countless. Praise be to God, Lord of the Worlds, that most of them demonstrated an understanding of the suffering of the exhausted Gazans, who are enduring war, siege, destruction, genocide, deliberate starvation, and the spread of epidemics, diseases, parasites, and harmful pests due to the unprecedented environmental devastation brought by the Israeli occupation. Palestinians, like the rest of the free world, hope that the Israeli war on the Gaza Strip (and the West Bank) will end and that a Palestinian state with Al-Quds (Jerusalem) as its capital will be established, allowing Palestinians to demonstrate their remarkable commitment to environmental protection on a broad scale. It is truly encouraging to see their dedication to conserving endangered species in terrestrial and marine environments, including very rare species in the Mediterranean, most notably the Whale Shark.

Acknowledgment

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to all who contributed to the completion of this modest study, the first of its kind in Palestine and the fourth in the Mediterranean region. Special thanks are due to the General Directorate of Fisheries at the Ministry of Agriculture, Gazan fishermen, and displaced Gazans who, despite their reluctance, were forced to consume Whale Shark meat due to the widespread and deliberate famine imposed upon them by the Israeli occupation during its war of genocide and ethnic cleansing, which began on October 7, 2023.

References

- Rowat D, Brooks KS (2012) A review of the biology, fishery and conservation of the whale shark Rhincodon typus. Journal of Fish Biology 80(5): 1019-1056.

- Bonfil R, Abdallah M (2004) Field identification guide to the sharks and rays of the red sea and Gulf of Aden. FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. FAO, Rome, Italy, p. 71.

- Rohner CA, Richardson AJ, Marshall AD, Weeks SJ, Pierce SJ (2011) How large is the world’s largest fish? Measuring whale sharks Rhincodon typus with laser photogrammetry. Journal of Fish Biology 78: 378-385.

- Kennedy PM (2022) Watch: Unbelievable scenes of a whale shark on the Spanish coast.

- Stevens JD (2007) Whale shark (Rhincodon typus) biology and ecology: A review of the primary literature. Fish Research 84: 4-9.

- Motta PJ, Maslanka M, Hueter RE, Davis RL, Parra RDL, et al. (2010) Feeding anatomy, filter-feeding rate, and diet of whale sharks Rhincodon typus during surface ram filter feeding off the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Zoology 113(4): 199-212.

- Rohner CA, Couturier LI, Richardson AJ, Pierce SJ, Prebble CE, et al. (2013) Diet of whale sharks Rhincodon typus inferred from stomach content and signature fatty acid analyses. Marine Ecology Progress Series 493: 219-235.

- Dogan M (2023) Characteristics & distribution of zooplankton community in Al-Shaheen oil field pelagic ecosystem. Department of Biological & Environmental Sciences, College of Arts & Sciences, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar, p. 96.

- Boldrocchi G (2020) Ecological factors affecting the whale shark occurrence in Djibouti and presence of contaminants in the trophic web. Department of Human Sciences, Territory and Innovation, University of Insubria, Como, Italy, p. 211.

- Boldrocchi G, Omar M, Azzola A, Bettinetti R (2020) The ecology of the whale shark in Djibouti. Aquatic Ecology 54(2): 535-551.

- Akhilesh KV, Shanis CPR, White WT, Manjebrayakath H, Bineesh KK, et al. (2012) Landings of whale sharks Rhincodon typus Smith, 1828 in Indian waters since protection in 2001 through the Indian Wildlife (Protection) act, 1972. Environmental Biology of Fishes 96: 713-722.

- Li W, Wang Y, Norman B (2012) A preliminary survey of whale shark Rhincodon typus catch and trade in China: An emerging crisis. Journal of Fish Biology 80(5): 1608-1618.

- Pierce SJ, Norman B (2016) Rhincodon typus. The IUCN red list of threatened species, p. eT19488A2365291.

- Rowat D, Womersley FC, Norman BM, Pierce SJ (2021) Global threats to whale sharks. Whale Shark Biology, Ecology, and Conservation (1st edn), p. 27.

- Hsu HH, Joung SJ, Liu KM (2012) Fisheries, management and conservation of the whale shark Rhincodon typus in Taiwan. Journal of Fish Biology 80(5): 1595-1607.

- Jones GP, Kaly UL (1995) Conservation of rare, threatened and endemic marine species in Australia. The State of the Marine Environment for Australia, pp. 183-191.

- Berumen ML, Braun CD, Cochran JE, Skomal GB, Thorrold SR (2014) Movement patterns of juvenile whale sharks tagged at an aggregation site in the red sea. PLoS One 9(7): e103536.

- Turan C, Ergüden D, Gürlek M (2016) Climate change and biodiversity effects in Turkish seas. Natural and Engineering Sciences 1(2): 15-24.

- Galil BS (2008) Alien species in the mediterranean sea-which, when, where, why? Hydrobiologia 606(1): 105-116.

- Galil B, Marchini A, Ambrogi AO, Ojaveer H (2017) The enlargement of the Suez Canal-Erythraean introductions and management challenges. Management of Biological Invasions 8(2): 141-152.

- Katsanevakis S, Zenetos A, Belchior C, Cardoso AC (2013) Invading european seas: Assessing pathways of introduction of marine aliens. Ocean & Coastal Management 76: 64-74.

- Otero M, Cebrian E, Francour P, Galil B, Savini D (2013) Monitoring marine invasive species in mediterranean marine protected areas (MPAs): A strategy and practical guide for managers. Malaga, Spain, IUCN, p. 133.

- Galil BS, Boero F, Campbell ML, Carlton JT, Cook E, et al. (2015) Double trouble: The expansion of the Suez Canal and marine bio invasions in the mediterranean sea. Biological Invasions 17(4): 973-976.

- Geh H (2025) Shark feast: Shock moment starving Gazans haul whale shark out of the sea & ‘butcher it for food’ as aid trickles in after ceasefire. The Sun-US Edition, USA.

- Rowat D, Gore M (2007) Regional scale horizontal and local scale vertical movements of whale sharks in the Indian Ocean off Seychelles. Fisheries Research 84(1): 32-40.

- Shawky AM, Maddalena AD (2013) Human impact on the presence of sharks at diving sites of the Southern Red Sea, Egypt. Bulletin of the Natural History Museum of Venice 64: 51-62.

- Hozumi A (2015) Environmental factors affecting the whale shark aggregation site in the south-central red sea. King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, p. 189.

- Hozumi A, Kaartvedt S, Røstad A, Berumen ML, Cochran JE, et al. (2018) Acoustic backscatter at a red sea whale shark aggregation site. Regional Studies in Marine Science 20: 23-33.

- Cochran JEM, Hardenstine RS, Braun CD, Skomal GB, Thorrold SR, et al. (2016) Population structure of a whale shark Rhincodon typus aggregation in the Red Sea. Journal of Fish Biology 89(3): 1570-1582.

- Cochran JE, Braun CD, Cagua EF, Campbell MF, Hardenstine RS, et al. (2019) Multi-method assessment of whale shark (Rhincodon typus) residency, distribution, and dispersal behavior at an aggregation site in the Red Sea. PLoS One 14(9): e0222285.

- Hardenstine RS (2020) Spots and sequences: Multi-method population assessment of whale sharks in the Red Sea. King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, pp. 178.

- Serena F, Abella AJ, Bargnesi F, Barone M, Colloca F, et al. (2020) Species diversity, taxonomy and distribution of Chondrichthyes in the mediterranean and black sea. The European Zoological Journal 87(1): 497-536.

- Turan C, Gürlek M, Ergüden D, Kabasakal H (2021) A new record for the shark fauna of the mediterranean sea: Whale shark, Rhincodon typus (Orectolobiformes: Rhincodontidae). In Annales: Series Historia Naturalis 31(2): 167-172.

- Aqdah AH (2025) For the first time, a whale shark has been spotted between latakia and Jableh. Alhurriyah.

- Athr Press (2025) Video shows whale shark spotted between Jableh and latakia for the first time in years.

- Sky News Arabia (2025) Egypt: Whale shark sparks fear on Dahab beaches, environment authorities issue warnings.

- Yalla Syria News (2025) A rare appearance of a whale shark off the coasts of Latakia and Jableh has sparked interest among fishermen and researchers.

- Abd Rabou AN (2020) The Palestinian marine and terrestrial vertebrate fauna preserved at the biology exhibition, Islamic university of Gaza, bombarded by the Israeli Army in December, 2008. Israa University Journal of Applied Science (IUGAS) 4(1): 9-51.

- Abd Rabou AN, Kichaoui AEY, Bashiti TAE, Aziz IIA, Elnabris KJ, et al. (2025) On the mummified marine and terrestrial vertebrate fauna adorning the biology department museum at the Islamic university of Gaza, Gaza strip, Palestine, before the Israeli War on October 7, 2023. Open Journal of Ecology (OJE)15(9): 528-568.

- Abd Rabou AN (2025) On the status of the loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta Linnaeus, 1758) (Reptilia: Testudines: Cheloniidae) in the Gaza strip, Palestine. Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography 7(3): 1-13.

- Abd Rabou AN (2025) On the status of the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas Linnaeus, 1758) (Reptilia: Testudines: Cheloniidae) in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography 7(4): 1-13.

- Beckley LE, Cliff G, Smale MJ, Compagno LJV (1997) Recent strandings and sightings of whale sharks in South Africa. Environ Biol Fishes 50: 343-348.

- Gunn JS, Stevens JD, Davis TLO, Norman BM (1999) Observations on the short-term movements and behavior of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) at Ningaloo reef, Western Australia. Mar Biol 135: 553-559.

- Eckert SA, Stewart BS (2001) Telemetry and satellite tracking of whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, in the sea of Cortez, Mexico, and the north Pacific Ocean. Environ Biol Fishes 60: 299-308.

- Eckert SA, Dolar LL, Kooyman GL, Perrin W, Rahman RA (2002) Movements of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) in South-east Asian waters as determined by satellite telemetry. J Zool 257: 111-115.

- Heyman W, Graham R, Kjerfve B, Johannes R (2001) whale sharks Rhincodon typus aggregate to feed on fish spawn in Belize. Marine Ecology Progress Series 215(1): 275-282.

- Burks CM, Driggers WB, Mullin KD (2006) Abundance and distribution of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Fishery Bulletin 104(4): 579-585.

- Castro ALF, Stewart BS, Wilson SG, Hueter RE, Meekan MG, et al. (2007) Population genetic structure of Earth's largest fish, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus). Molecular Ecology 16(24): 5183-5192.

- Martin RA (2007) A review of behavioral ecology of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus). Fisheries Research 84(1): 10-16.

- Venegas RDLP, Hueter R, Cano JG, Tyminski J, Remolina JG, et al. (2011) An unprecedented aggregation of whale sharks, Rhincodon typus, in Mexican coastal waters of the Caribbean Sea. Plos One 6(4): e18994.

- Rowat D, Brooks K, March A, McCarten C, Jouannet D, et al. (2011) Long-term membership of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) in coastal aggregations in Seychelles and Djibouti. Mar Freshw Res 62: 621-627.

- McKinney JA, Hoffmayer ER, Wu W, Fulford R, Hendon JM (2012) Feeding habitat of the whale shark Rhincodon typus in the northern Gulf of Mexico determined using species distribution modeling. Marine Ecology Progress Series 458: 199-211.

- Sequeira AM, Mellin C, Meekan MG, Sims DW, Bradshaw CJ (2013) Inferred global connectivity of whale shark Rhincodon typus Journal of Fish Biology 82(2): 367-389.

- Palomo NC, Silveira JH, Abunader IV, Reyes O, Ordoñez U (2015) Distribution and feeding habitat characterization of whale sharks Rhincodon typus in a protected area in the north Caribbean Sea. Journal of Fish Biology 86(2): 668-686.

- Robinson DP (2016) The ecology of whale sharks Rhincodon typus within the Arabian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. Heriot-Watt University, Scotland.

- Jawad LA, Dirawi AAM, Hilali A, HI, Asadi A, et al. (2019) Observations of stranded and swimming whale sharks Rhincodon typus in Khor Al‐Zubair, NW Arabian Gulf and Shatt Al‐Arab Estuary, Iraq. Journal of Fish Biology 94(2): 330-334.

- Báez JC, Barbosa AM, Pascual P, Ramos ML, Abascal F (2020) Ensemble modeling of the potential distribution of the whale shark in the Atlantic Ocean. Ecology and Evolution 10(1): 175-184.

- Khalaf NA (2026) A rare catch of a whale shark (Rhincodon typus Smith, 1828) off the Khan Younis coast, southern Gaza Strip: The second record from the Palestinian mediterranean coast. Gazelle: The Palestinian Biological Bulletin 44(237): 1-14.

- Sequeira AM, Mellin C, Fordham DA, Meekan MG, Bradshaw CJ (2014) Predicting current and future global distributions of whale sharks. Global Change Biology 20(3): 778-789.

- Turnbull SD, Randell JE (2006) Rare occurrence of a Rhincodon typus (whale shark) in the Bay of Fundy, Canada. Northeastern Naturalist 13(1): 57-58.

- Boitani L, Bartoli S (1983) Simon and Schuster’s guide to mammals. Simon and Schuster Inc, USA, p. 511.

- Castro p, Huber ME (2009) Marine biology (7th edn), McGraw-Hill, Ohio, USA, p. 459.

- Bariche M (2012) Field identification guide to the living marine resources of the eastern and southern mediterranean. FAO Species Identification Guide for Fishery Purposes. FAO, Rome, Italy, p. 610.

- Turan C, Gürlek M, Başusta N, Uyan A, Doğdu SA, et al. (2018) A Checklist of the non-indigenous fishes in Turkish marine waters. Natural and Engineering Sciences 3: 333-358.

- Maddalena AD, Bänsch H, Heim W (2015) Sharks of the mediterranean: An illustrated study of all species kindle edition. McFarland, USA, p. 236.

- Sattler L (2025) Helicopter captures video of world's largest fish in unexpected location: "First documented sighting". The Cool Down.

- The Media Line (2025) Whale shark that captivated Israelis found dead after being Caught in Gaza.

- Ynet Global (2025) Rare whale shark that drew crowds in Israel caught and killed in Gaza.

- Rodrigues NV, Correia JPS, Graça JTC, Rodrigues F, Pinho R, et al. (2012) First record of a whale shark Rhincodon typus in continental Europe. Journal of Fish Biology 81(4): 1427-1429.

- Weinman S (2022) What’s a Whale Shark doing in the Med? Scuba News.

- Colman J (1997) A review of the biology and ecology of the whale shark. Journal of Fish Biology 51(6): 1219-1234.

- Guzman HM, Collatos CM, Gomez CG (2022) Movement, behavior, and habitat use of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) in the Tropical Eastern Pacific Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Sciences 9: 793248.

- McMurray K (2016) Whale shark freed from entanglement.

- Escalle L, Murua H, Amande JM, Arregui I, Chavance P, et al. (2016) Post‐capture survival of whale sharks encircled in tuna purse‐seine nets: Tagging and safe release methods. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 26(4): 782-789.

- Duncan EM, Botterell ZL, Broderick AC, Galloway TS, Lindeque PK, et al. (2017) A global review of marine turtle entanglement in anthropogenic debris: A baseline for further action. Endangered Species Research 34: 431-448.

- Reinert TR, Spellman AC, Bassett BL (2017) Entanglement in and ingestion of fishing gear and other marine debris by Florida manatees 1993 to 2012. Endangered Species Research 32: 415-427.

- Parton KJ, Galloway TS, Godley BJ (2019) Global review of shark and ray entanglement in anthropogenic marine debris. Endangered Species Research 39: 173-190.

- Brown AH, Niedzwecki JM (2020) Assessing the risk of whale entanglement with fishing gear debris. Marine Pollution Bulletin 161(Pt A): 111720.

- Abd Rabou AN (2025) A look at the by-catch and stranding of Leatherback Sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea Vandelli 1761) (Reptilia: Testudines: Dermochelyidae) in the Gaza Strip-Palestine. JOJ Wildlife & Biodiversity 5(3): 555664.

- Abd Rabou AN (2023) The first record of the Mediterranean Monk Seal (Monachus monachus Hermann 1779) in the marine coast of the Gaza Strip, Palestine. International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies 10(3): 29-35.

- Abd Rabou AN, Rabou MAA, Rabou OAA (2023) On the arrival of the rare and endangered Mediterranean Monk Seal-Yulia (Monachus monachus Hermann, 1779) on the shores of Jaffa, Palestine (May 2023). International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies 10(3): 19-23.

- Abd Rabou AN, Mohanna AM, Bakheet BA, Toima RMA, Ashour LZ, et al. (2025) First record of the Striped Dolphin (Stenella coeruleoalba Meyen, 1833) in the Gaza Strip and its consumption during the famine in the midst of the Israeli war following October 7, 2023. Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography 7(5): 1-8.

- Abd Rabou AN, Rabou MAA, Qaraman AA, Abualtayef MT, Rabou AAA, et al. (2021) Sightings and strandings of the cetacean fauna in the mediterranean coast of the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Israa University Journal of Applied Science (IUGAS) 5(1): 152-186.

- Abd Rabou AN, Elkahlout KE, Elnabris KJ, Attallah AJ, Salah JY, et al. (2023) An inventory of some relatively large marine mammals, reptiles and fishes sighted, caught, by-caught or stranded in the mediterranean coast of the Gaza Strip-Palestine. Open Journal of Ecology (OJE) 13(2): 119-153.

- Abd Rabou AN (2025) Amid the Israeli War on the Gaza Strip, Palestine, which has been ongoing since October 7, 2023, famine is driving Gazans to eat the meat of globally endangered sea turtles. Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography 7(5): 1-8.

- IUCN (2012) Marine mammals and sea turtles of the Mediterranean and Black Seas. Gland, Switzerland and Malaga, Spain, pp. 1-32.

- Stewart BS, Wilson SG (2005) Threatened fishes of the world: Rhincodon typus (Smith 1828) (Rhincodontidae). Environmental Biology of Fishes 74: 184-185.

- Rowat D, Meekan MG, Engelhardt U, Pardigon B, Vely M (2007) Aggregations of juvenile whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) in the Gulf of Tadjoura, Djibouti. Environmental Biology of Fishes 80: 465-472.

- Pravin P (2000) Whale shark in the Indian coast: Need for conservation. Current Science 79(3): 310-315.

- Chen CT, Liu KM, Joung SJ (2002) Preliminary report on Taiwan’s whale shark fishery. Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management. Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, pp. 162-167.

- White WT, Cavanagh RD (2007) Whale shark landings in Indonesian artisanal shark and ray fisheries. Fisheries Research 84(1): 128-131.

- Nijman V (2023) Illegal trade in protected sharks: The case of artisanal whale shark meat fisheries in Java, Indonesia. Animals (Basel) 13(16): 2656.

- Adam M (2005) Is shark meat Halal? Darul Iftaa Leicester, UK.

- Wu G (2016) Dietary protein intake and human health. Food Function 7(3): 1251-1265.

- Elmadfa I, Meyer AL (2017) Animal proteins as important contributors to a healthy human diet. Annual Review of Animal Biosciences 5: 111-131.

- Mishra SP, Pradesh U (2020) Significance of fish nutrients for human health. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Research 5(3): 47-49.

- Kiros G, Hogan DP (2000) The impact of famine, war, and environmental degradation on infant and early child mortality in Africa: The case of Tigrai, Ethiopia. Genus 5(3/4): 145-178.

© 2025 Abdel Fattah N Abd Rabou*. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)