- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Telemedicine & E-health

Investigating Inflammatory and Hematological Parameters in Myasthenia Gravis Patients in Owerri, Nigeria

Onu Mercy O1*, Aloy-Amadi Oluchi C1, Enyereibe Marvellous U1, Okpara Emmanuel N1,Iheanacho Malachy C2 and Nsonwu Magnus C3

1 Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Imo State University, Nigeria

2 Department of Haematology and Blood Transfusion, Federal Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

3 Department of Optometry, Imo State University, Nigeria

*Corresponding author:Onu Mercy O, Department of Medical Laboratory Science, Imo State University, Owerri, Nigeria

Submission: December 18, 2025;Published: January 29, 2026

ISSN: 2689-2707 Volume 6 Issue 3

Abstract

Background: Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is an autoimmune neuromuscular disorder characterized by

fluctuating skeletal muscle weakness. Inflammatory and hematological markers, such as Erythrocyte

Sedimentation Rate (ESR), leukocyte profiles and fibrinogen levels, may reflect disease activity, but their

clinical relevance in MG is not well established.

Objective: To investigate hematological parameters, including leukocyte differentials, ESR, and fibrinogen

levels, in MG patients compared to healthy controls.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted involving 20 MG patients and 20 age-and sex-matched

healthy controls. Venous blood samples were analyzed for total and differential leukocyte counts, ESR, and

plasma fibrinogen. Data were expressed as mean±standard deviation and compared using independent

t-tests and Pearson correlation analyses.

Result: MG patients exhibited significantly higher ESR (79.40±41.20)mm/hr and fibrinogen levels

(432.67±105.66)mg/dL compared to controls (21.23±7.55)mm/hr and (256.40±115.59)mg/dL,

respectively, (p<0.0001). Lymphocyte (55.23±6.95)% vs (38.37±9)%, (p<0.0001) and monocyte counts

(7.27±5.13)% vs (2.40±3.15)%, (p<0.0001) were elevated, whereas neutrophil counts were reduced

(35.80±8.28)% vs (58.10±10.43)%, (p<0.0001) in MG patients. Fibrinogen levels positively correlated

with lymphocytes and monocytes, and negatively with neutrophils.

Conclusion: MG is associated with systemic inflammation, reflected by elevated ESR and fibrinogen and

altered leukocyte profiles. Routine assessment of these parameters may aid in disease monitoring and

risk stratification in MG patients.

Keywords:Myasthenia gravis; Inflammation; ESR; Fibrinogen; Leukocytes

Introduction

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is a chronic autoimmune disorder affecting the neuromuscular junction, leading to fluctuating skeletal muscle weakness and fatigue [1,2]. The disease occurs when autoantibodies target the Acetyl-Choline Receptor (AChR) or associated proteins such as Muscle-Specific Kinase (MuSK), impairing signal transmission between nerves and muscles [3,4]. MG can present as ocular or generalized forms, and its pathogenesis involves both humoral and cellular immune responses [5]. Several studies have highlighted the role of inflammation in the progression of MG. Elevated markers of systemic inflammation, including Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and acute-phase proteins such as fibrinogen, have been associated with disease severity [6,7]. Additionally, immune cell populations such as lymphocytes and monocytes are implicated in autoimmune responses, while neutrophil levels may reflect disease-modifying effects or immune dysregulation [8,9]. Despite these insights, few studies have systematically analyzed the hematological profiles of MG patients in African populations, creating a knowledge gap in the regional understanding of the disease [10]. The present study aims to evaluate hematological parameters, including ESR, differential white blood cell counts, and fibrinogen levels in MG patients compared to healthy controls. We also assess correlations between fibrinogen and leukocyte counts, alongside the impact of age and sex on these parameters.

Materials and Methods

Study design and population

This case-control study recruited 20 clinically diagnosed MG patients from tertiary hospitals in Owerri, Nigeria, alongside 20 age-and sex-matched healthy controls. Inclusion criteria for MG patients included confirmed diagnosis through clinical evaluation and presence of autoantibodies against AChR or MuSK. Exclusion criteria included concurrent infections, pregnancy, or use of immunosuppressive therapy within the past 3 months. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board, and informed consent was collected from all participants [11].

Sample collection

Venous blood samples (5mL) were collected from each participant into EDTA and citrate tubes for hematological and fibrinogen analyses, respectively. Samples were processed within 2 hours of collection.

Hematological analysis

Differential white blood cell counts (neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils) and ESR were determined using standard laboratory protocols [12,13]. Fibrinogen levels were quantified using the Clauss method [14].

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 27. Descriptive statistics included mean±Standard Deviation (SD). Group comparisons were performed using independent t-tests and Pearson correlation coefficients assessed relationships between fibrinogen and other parameters. Significance was set at p<0.05 [15].

Result

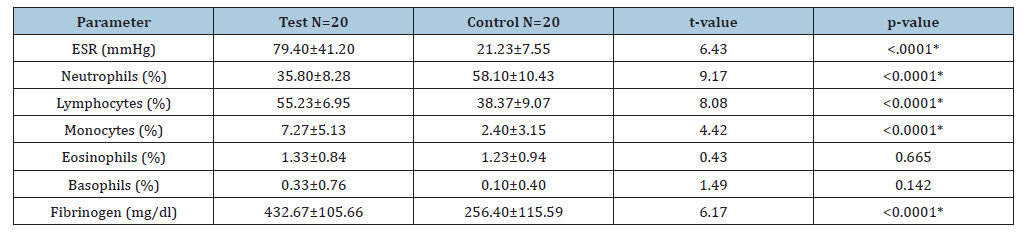

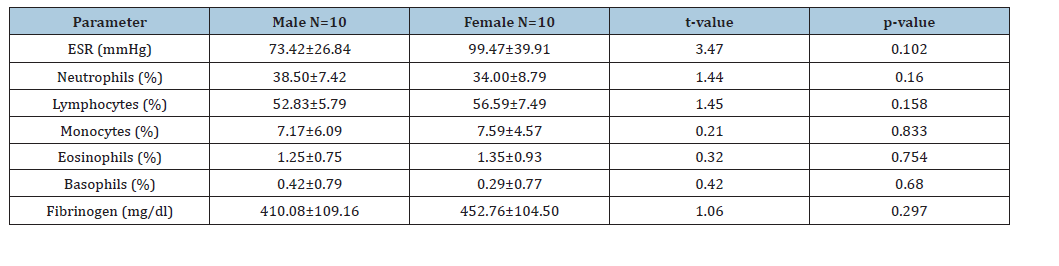

The mean values of ESR (79.40±41.20)mmHg, lymphocyte (55.23±6.95)%, monocyte (7.27±5.13)% and fibrinogen (432.67±105.66)mg/dl were significantly raised in Myasthenia gravis patients when compared to controls (21.23±7.55)mmHg, (38.37±9.07)%, (2.40±3.15)%, (256.40±115.59)mg/dl(t=6.43, p<0.0001; t=8.08, p<0.0001; t=4.42, p<0.0001 and t=6.17, p<0.0001). The mean value of neutrophils (35.80±8.28)% was significantly reduced in Myasthenia gravis patients when compared to controls (58.10±10.43)% (t=9.17, p<0.0001) (Table 1). There was no significant increase in the mean values of eosinophils (1.33±0.84)% and basophils (0.33±0.76)% in Myasthenia gravis patients when compared to controls (1.23±0.94)% and (0.10±0.40)% (t=0.43, p<0.0001 and t=1.49, p<0.0001) (Table 2). There was no significant reduction in the mean values of ESR (73.42±26.84) mmHg, lymphocytes (52.83±5.79)%, monocytes (7.17±6.09)%, eosinophils (1.25±0.75)% and fibrinogen (410.08±109.16)mg/dl in male patients with Myasthenia gravis patients when compared to females (99.47±39.91)mmHg, (34.00±8.79)%, (56.59±7.49)%, (7.59±4.57)%, (1.35±0.93)%, (0.29±0.77)% and (452.76±104.50) mg/dl (t=3.47, p=0.102; t=1.45, p=0.160; t=0.21, p=0.833; t=0.32, p=0.754 and t=1.06 and p=0.297).

Table 1:Mean value of ESR, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils and fibrinogen in myasthenia gravis versus control (Mean±SD). KEY: *: Significant, SD: Standard Deviation, ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate.

Table 2:Mean value of ESR, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils and fibrinogen in male myasthenia gravis and female myasthenia gravis (Mean±S.D). KEY: *: Significant, SD: Standard Deviation, ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate.

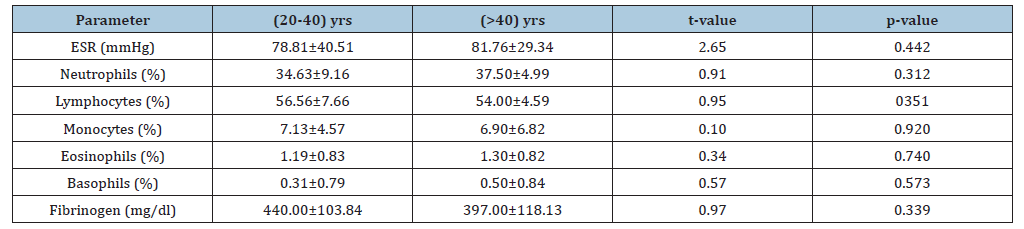

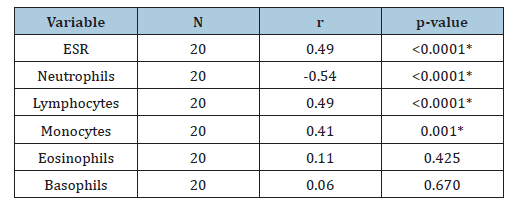

On the hand, there was no significant difference in the mean values of neutrophils (38.50±7.42)% and basophils (0.42±0.79)% in male patients with Myasthenia gravis when compared to the females (34.00±8.79) % and (0.29±0.77) % respectively (t=1.44, p=0.160 and t=0.42, p=0.680) (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the mean values of ESR (78.81±40.51)mmHg, neutrophils (34.63±9.16)%, eosinophils (1.19±0.83)% and basophils (0.31±0.79)% in Myasthenia gravis patients of ages (20-40)yrs when compared to Myasthenia gravis patients of ages (>40)yrs (81.76±29.34)mmHg, (37.50±4.99)%, (54.00±4.59)%, (6.90±6.82)%, (1.30±0.82)%, (t=2.65, p=0.442; t=0.91, p=0.312; t=0.34, p=0.351 and t=0.57 p=0.573). Similarly, there was no significant difference in the mean values of lymphocytes (56.56±7.66)%, monocytes (7.13±4.57)%, fibrinogen (440.00±103.84)mg/dl in patients with Myasthenia gravis of ages (20-40)years, when compared to those of ages (>40)years, (54.00±4.59)%, (6.90±6.82)% and (397.00±118.13)mg/dl (t=0.95, p=0.351; t=0.10, p=0.920 and t=0.97, p=0.339) (Table 4). There was a significant positive correlation of fibrinogen with ESR, lymphocyte and monocyte in Myasthenia gravis patients (r=0.49, p<0.0001; r=0.49, p<0.0001 and r=0.41, p=0.001). There was a significant negative correlation of fibrinogen with neutrophils in Myasthenia gravis patients (r=-0.54, p<0.0001) and a non- significant positive correlation of fibrinogen with eosinophils and basophils in Myasthenia gravis patients (r=0.11, p=0.425 and r=0.06, p=0.670).

Table 3:Mean Values of ESR, neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, eosinophils, basophils and fibrinogen in myasthenia gravis of age (20-40) yrs versus myasthenia gravis of age (>40) yrs (Mean±SD). KEY: *: Significant, SD: Standard Deviation, ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate.

Table 4:Correlation of fibrinogen with ESR and differential count in patients with myasthenia gravis patients. KEY: *: Significant, SD: Standard Deviation, ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate.

Discussion

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disorder predominantly affecting neuromuscular transmission, leading to fluctuating muscle weakness and fatigue. The present study evaluated hematological and inflammatory markers, including ESR, leukocyte differentials and fibrinogen levels, in MG patients compared to healthy controls. Our findings demonstrate significant alterations in these parameters, indicating systemic inflammation and immune dysregulation in MG. ESR is a nonspecific marker of inflammation and has been widely used to assess systemic inflammatory activity in autoimmune diseases [16]. In this study, ESR was markedly elevated in MG patients compared to controls, suggesting active inflammatory processes. This finding aligns with previous reports indicating increased ESR in autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis [17]. Fibrinogen, an acute-phase reactant synthesized in the liver, is elevated during inflammatory states and contributes to hypercoagulability [18]. MG patients showed significantly higher fibrinogen levels than controls. Elevated fibrinogen may reflect immune-mediated endothelial activation, which is common in autoimmune conditions [19]. Notably, fibrinogen correlated positively with ESR, lymphocytes and monocytes and negatively with neutrophils, highlighting its central role as a marker of systemic inflammation in MG.

Leukocyte profiling revealed significant increases in lymphocytes and monocytes while neutrophils were significantly reduced in MG patients. These findings suggest a shift toward adaptive immunity dominance, consistent with the autoimmune nature of MG [20]. Lymphocytes, particularly CD4+ T-helper cells and autoreactive B cells, mediate antibody production against acetylcholine receptors or MuSK proteins [3]. Elevated monocytes may reflect enhanced antigen presentation and cytokine production, further promoting autoimmunity [21]. Conversely, reduced neutrophil counts might result from immune suppression or redistribution due to chronic inflammation [22]. Eosinophil and basophil counts were not significantly altered, indicating that MGassociated inflammation predominantly involves lymphoid and monocytic pathways. The observed positive correlation between fibrinogen and lymphocytes/monocytes reinforces the interplay between systemic inflammation and immune cell activation in MG. Fibrinogen can modulate immune cell behavior, including promoting lymphocyte adhesion and monocyte differentiation [23]. The negative correlation with neutrophils may indicate compensatory redistribution or consumption during inflammation. These findings are consistent with other autoimmune studies, which demonstrate that acute-phase proteins and immune cells act synergistically to sustain chronic inflammation [18].

No statistically significant differences were observed in hematological parameters and fibrinogen levels based on sex or age. This suggests that, within this cohort, systemic inflammation and leukocyte alterations in MG are independent of these demographic variables. Previous studies have reported similar findings, although some indicate that disease severity may vary slightly between sexes due to hormonal influences [24]. The study highlights that routine hematological parameters, such as ESR, lymphocyte and monocyte count and fibrinogen levels, may serve as accessible biomarkers for MG disease activity. These markers can complement clinical evaluation and antibody testing, providing additional insight into systemic inflammation. Moreover, monitoring fibrinogen levels may help identify patients at risk of thrombotic complications, as hyperfibrinogenaemia has been linked to increased cardiovascular risk [25]. This study provides valuable insight into the inflammatory and hematological profiles of MG patients in a Nigerian cohort, which is currently underrepresented in the literature. However, limitations include the relatively small sample size, potential variability in disease duration and treatment, and lack of longitudinal follow-up to assess changes over time. Future studies should include larger, multi-center cohorts and explore the impact of specific therapies on these parameters.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that MG is associated with systemic inflammation, evidenced by elevated ESR and fibrinogen levels, and altered leukocyte profiles, specifically increased lymphocytes and monocytes and reduced neutrophils. These parameters correlate with one another, underscoring the interconnected nature of inflammation and immune dysregulation in MG. Age and sex do not appear to influence these hematological alterations. Routine assessment of ESR, lymphocyte and monocyte count and fibrinogen may provide cost-effective biomarkers for disease monitoring and risk stratification in MG patients.

References

- Gilhus NE (2016) Myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med 375: 2570-2581.

- Meriggioli MN, Sanders DB (2009) Autoimmune myasthenia gravis: Emerging clinical and biological heterogeneity. Lancet Neurol 8(5): 475-490.

- Vincent A, Palace J, Hilton JD (2001) Myasthenia gravis. Lancet 357: 2122-2128.

- Tüzün E, Christadoss P (2013) Autoantibodies in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmune Rev 12: 918-923.

- Skeie GO, Apostolski S, Evoli A, Gilhus NE, Illa I, et al. (2010) Guidelines for the treatment of autoimmune neuromuscular junction transmission disorders. Eur J Neurol 17(7): 893-902.

- Herrlinger U, Weiler M, Falk W (2022) Inflammatory markers in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev 21: 103053.

- Favalaro G, Lippi G (2020) Hematological biomarkers of inflammation. Clin Chem Lab Med 58: 1-12.

- Bolliger D, Seeberger MD, Koller MT (2017) White blood cell subtypes in autoimmune diseases. Thromb Res 154: 63-70.

- Mohamed MA (2015) Leukocyte profiles in chronic inflammation. J Immunol Res p. 123456.

- Nwosu MC (2021) Autoimmune neuromuscular disorders in sub-Saharan Africa. Pan Afr Med J 39: 22.

- World Medical Association (2013) Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 310(20): 2191-2194.

- Cheesbrough M (2006) District laboratory practice in tropical countries. (2nd edn), Cambridge University Press, USA, pp.1-434

- Dacie JV, Lewis SM (2017) Practical haematology. (12th edn), Churchill Livingstone, London.

- Clauss A (1957) Rapid physiological coagulation method in plasma. Thromb Haemost 1: 829-835.

- Field A (2013) Discovering statistics using SPSS. (4th edn), Los Angeles, US.

- Brigden ML (1999) Clinical utility of ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate). Am Fam Physician 60(5): 1443-1450.

- Wolfe F (1992) ESR in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 35: 126-136.

- Gabay C, Kushner I (1999) Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med 340(6): 448-454.

- Ridker PM (2001) Fibrinogen and cardiovascular risk. Circulation 103: 1813-1818.

- Dalakas MC (2004) Pathogenesis of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol 55: 12-21.

- Liu Y (2017) Monocytes in autoimmune disorders. Autoimmun Rev 16: 1220-1227.

- Pillay J (2012) Neutrophil dynamics in inflammation. Blood 120: 1137-1146.

- Flick MJ (2004) Fibrinogen Modulation of leukocyte function. J Immunol 172: 4457-4463.

- Heckmann JM (2011) Sex Differences in autoimmune neuromuscular diseases. Muscle Nerve 44: 387-394.

- Ernst E, Resch KL (1993) Fibrinogen as a cardiovascular risk factor. A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Lancet 341: 1085-1086.

© 2026 Onu Mercy O. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)