- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Telemedicine & E-health

Can Formula-Assisted Venous Sampling Reliably Estimate Arterial Blood Gases?

Erturk Zamir Kemal1*, Evrin Togay2, Ekinci Berkay3, Candar Tugba4 and Erturk Bahadir5

1The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK), Türkiye

2Department of Emergency Medicine, Ufuk University Faculty of Medicine, Türkiye

3Department of Cardiology, Ufuk University Faculty of Medicine, Türkiye

4Department of Biochemistry, Ufuk University Faculty of Medicine, Türkiye

5Kaman District Health Department, Türkiye

*Corresponding author:Erturk Zamir Kemal, The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK), Ankara, Türkiye

Submission: September 17, 2025;Published: December 19, 2025

ISSN: 2689-2707 Volume 6 Issue 2

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate agreement between simultaneously obtained peripheral venous and Arterial

Blood Gas (ABG) values (pH, pCO2, pO2, HCO3-) in emergency department patients and to quantify the

incremental value of applying published and newly derived conversion (“arterialization”) formulas with

respect to Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) acceptability.

Methods: This prospective study enrolled 105 adult patients requiring ABG analysis (May-September

2016). Simultaneous arterial and peripheral venous samples were analyzed on a single blood gas

analyzer. Paired comparisons used paired t tests, Pearson correlation, and Bland-Altman analysis. Linear

regression (multivariable for pO2) generated new formulas; performance was compared with previously

published models. The proportions of raw venous and arterialized (formula-adjusted) venous results

outside CLIA limits were calculated.

Result: Venous and arterial values differed systematically but showed strong linear relationships for

pH, pCO2, and HCO3-, while the association for pO2 was only moderate before adjustment. Applying

conversion formulas materially improved clinical acceptability: For example, the proportion of venous

pCO2 values outside CLIA limits was cut from nearly one half of paired samples to roughly one eighth,

and venous pH discordance similarly fell by more than half. Bicarbonate exhibited minimal bias and

high concordance even before adjustment, with only modest incremental gain. Although a multivariable

equation noticeably increased correlation for pO2, the limits of agreement remained too wide to justify

substituting venous-based estimates for direct arterial oxygen assessment.

Conclusion: Simple conversion formulas substantially improve venous estimation of arterial pH, pCO2,

and HCO3- and may reduce the need for some arterial punctures in emergency practice. Venous-based

estimation of pO2 remains unreliable and should not replace direct arterial measurement for assessing

oxygenation.

Keywords:Arterial blood gas; Venous blood gas; Conversion formula; Agreement; Emergency department; Bicarbonate

Introduction

Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) analysis is accepted as the gold standard method for demonstrating acid-base balance in the evaluation of metabolic and respiratory diseases [1]. However, the procedure requires experience, is painful and carries risks of various complications, making its routine application challenging. In clinical practice, the radial, brachial and femoral arteries are most frequently selected; arterial injury, thrombosis that may cause distal ischemia, hemorrhage and aneurysm formation are among the most common complications [2]. The likelihood of these complications increases further with repeated sampling attempts [3]. In diseases such as COPD, pulmonary embolism, and congestive heart failure that present with hypoxemia and dyspnea, arterial blood gas analysis is frequently performed for differential diagnosis and treatment monitoring, exposing patients to similar risks each time. In recent years, Venous Blood Gas (VBG) analysis has been increasingly investigated in clinical practice because of its potential to predict arterial parameters. It is being considered as an alternative or complementary method to invasive arterial sampling, particularly in emergency departments, intensive care units, and home healthcare settings. Moreover, the storage of these data in cloud-based systems via telemedicine applications and their processing with artificial intelligence algorithms now enables prediction of arterial values from venous parameters through learning from large datasets; this contributes substantially to clinical decision support systems.

Numerous studies have been published on this topic. In their emergency department study comparing arterial and venous blood gas parameters, Bakoğlu et al. [1] reported a strong correlation between arterial and venous pH, pCO2 and HCO3⁻ values, while the correlation between pO2 and sO2 was weak. In a multicenter prospective study, Boulain et al. [4] examined the effectiveness of samples obtained from the central venous system in estimating arterial blood gas and lactate levels; they stated that venous pH, pCO2, sO2 and lactate values could be used-via various formulasto estimate arterial blood gas in cardiac patients, although the results were not perfectly concordant. Ak et al. [5] demonstrated that pH, pCO2, and HCO3⁻ values obtained from venous blood gas analysis reliably predicted arterial results in patients presenting with COPD exacerbation. Lemoel et al. [6] developed an approach to predict arterial values from venous blood gas using the SpvO2 parameter and reported a marked improvement in detecting arterial blood gas abnormalities when SpvO2 adjustment was added to raw data. In light of these findings, the aim of our study was to collect simultaneous arterial and venous blood gas samples from patients presenting to the emergency department with an indication for arterial blood gas analysis and to compare the pCO2, pO2, bicarbonate, and pH parameters; additionally, we sought to investigate the predictability of arterial values from venous parameters using mathematical formulas previously described in the literature.

Materials and Methods

Study design and ethical approval

This prospective clinical study was conducted in the Emergency Department of Ufuk University School of Medicine between 01 May 2016 and 30 September 2016. Patients for whom arterial blood gas analysis was clinically indicated and who agreed to participate were informed about the study and provided written informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ufuk university non‑interventional scientific research evaluation commission. The principles of the world medical association declaration of Helsinki were observed throughout the study.

Sample and sampling method

A total of 105 patients who met the inclusion criterion of having a clinical indication for arterial blood gas analysis and who consented to participate were enrolled. For each patient, arterial and venous blood gas samples were drawn simultaneously. Venous blood gas samples were obtained through the intravenous line placed in the antecubital region and collected into heparinized negative‑pressure vacuum tubes. For arterial blood gas sampling, the radial artery was the first choice; in cases where this was not suitable, the femoral artery was punctured. Prefilled blood gas syringes (Plasti-med Blood Gas Syringe, 2mL, Turkey) containing 72 IU lithium heparin and fitted with a 22-gauge needle were used for arterial sampling.

Analytical method

All blood gas samples were analyzed on the blood gas analyzer located in the resuscitation room of the emergency department (Radiometer ABL800 BASIC, Denmark). The arterial and venous parameters obtained were compared with the acceptable error limits reported by the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) [7].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics for windows, Version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of distribution of variables was assessed using visual methods (histograms and probability plots) and analytical tests (Kolmogorov-Smirnov, Shapiro-Wilk). Descriptive statistics for normally distributed variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation. Paired t‑tests were used to compare simultaneous arterial and venous measurements. Agreement between the two methods was examined with Bland-Altman plots. Additionally, regression analysis was conducted to investigate the ability of venous parameters to predict arterial values. A p value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Result

pH

The mean arterial pH was 7.42±0.04 (range: 7.31-7.55), while the

mean venous pH was 7.40±0.05 (range: 7.25-7.51). The difference

between the two values was statistically significant (paired t test,

p<0.001). A strong correlation was observed (Pearson’s r=0.820,

p<0.001). Linear regression analysis was performed with arterial

pH as the dependent variable, resulting in the following predictive

model:

aV1pH = 1.73 + 0.77 × VpH (this study)

Other models reported in the literature were as follows:

aV2pH = 0.138 + 0.9851 × VpH [8]

aV3pH = 1.004 × VpH [5]

aV4pH = 0.763 × VpH + 1.786 [9]

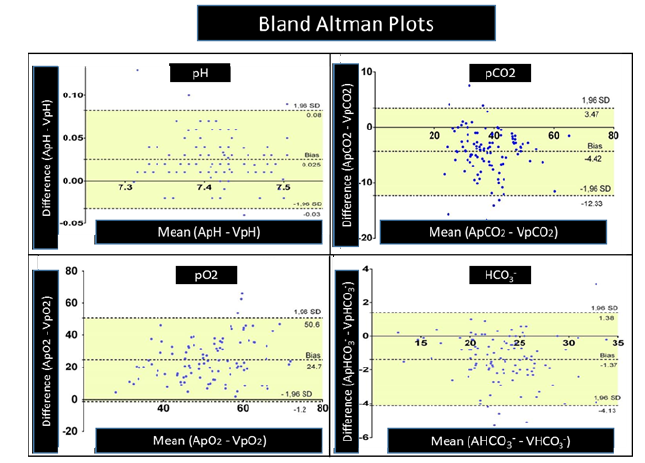

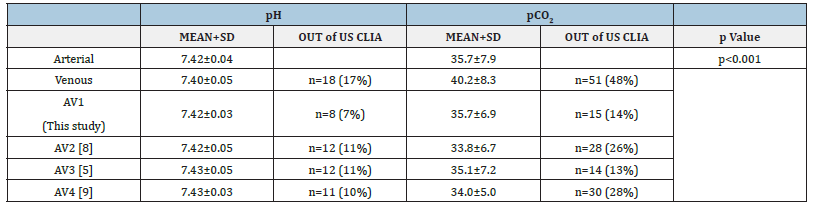

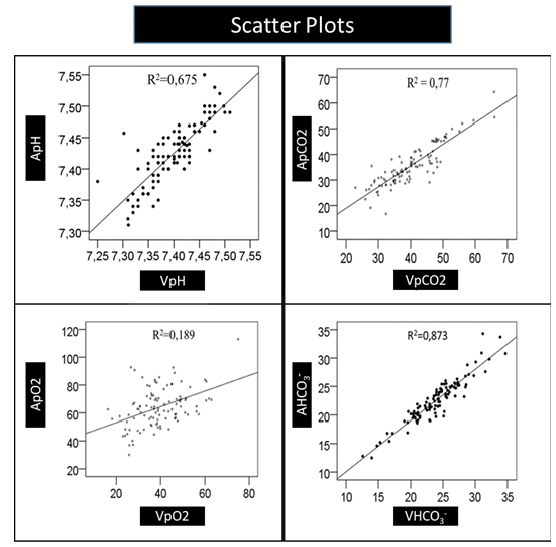

Scatter plot analysis showed a linear relationship (R²=0.675), and Bland-Altman plots indicated minimal bias (Figure 1 & Table 1). The study formula (aV1pH) yielded an absolute reduction of approximately 10 percentage points (from 17% to 7%) in out-oflimit venous pH results versus unadjusted values. All previously published formulas (aV2pH-aV4pH) likewise produced clinically meaningful decreases compared with raw venous values (Table 1).

Figure 1:Bland-Altman plots of venous and arterial pH.

Table 1:Comparison of arterial and venous blood gas parameters between groups.

pCO₂

The mean arterial pCO₂ was 35.7±7.9mmHg (range: 16.7-64.3),

whereas the mean venous pCO₂ was 40.2±8.3mmHg (range: 22.9-

66.0). The difference between arterial and venous pCO₂ values was

statistically significant (paired t test, p<0.001). A strong correlation

was observed (Pearson’s r=0.878, p<0.001). Linear regression

analysis generated the following predictive model:

aV1pCO₂ = 0.834 × VpCO₂ + 2.253 (this study)

Comparison with previously published models yielded:

aV2pCO₂ = 0.806 × VpCO₂ + 1.457 [8]

aV3pCO₂ = 0.873 × VpCO₂ [5]

aV4pCO₂ = 0.611 × VpCO₂ + 9.521 [9]

Scatter plot analysis demonstrated a high linear fit (R²=0.77). Bland-Altman plots showed that most values were within the limits of agreement (Figure 1 & Table 1). Unadjusted venous pCO2 exceeded CLIA limits in 51/106 (48%) pairs. Arterialization markedly reduced discordant results. The best-performing model for pCO2 (aV3pCO2) achieved an absolute reduction of 34.8 percentage points (48.0%→13.2%), corresponding to a relative reduction of about 72.5% in out-of-limit results compared with raw venous values. The study model (aV1pCO2) performed similarly (14.2%). These findings indicate a clinically meaningful improvement in meeting CLIA acceptability through formula-based arterialization (Table 1).

Correlation between arterialized venous pO₂ and arterial pO₂ was higher (r=0.791, p<0.001). Scatter plot analysis showed a weak linear fit (R²=0.189). Bland-Altman plots indicated wide limits of agreement (Figure 1).

HCO₃⁻

The mean arterial HCO₃⁻ value was 22.5±3.7mmol/L, while the

venous value was 23.9±3.9mmol/L. The difference between arterial

and venous HCO₃⁻ values was statistically significant (p<0.001).

A very strong correlation was observed (Pearson’s r=0.935,

p<0.001). Regression analysis showed that venous bicarbonate was

a significant predictor of arterial bicarbonate, while venous pCO₂

was not. The following model was obtained:

aVHCO₃⁻ = 0.9 × VHCO₃⁻ + 1 (this study)

Scatter plot analysis demonstrated a strong linear fit (R²=0.873). Bland-Altman plots showed minimal bias between measurements (Figure 1).

Discussion

In this study we examined how closely peripheral venous blood gas results (pH, pCO2, pO2, HCO3-) reflect arterial values and what clinical value “Arterialized” (aV) prediction formulas derived from venous measurements add compared with raw venous results. The findings show that the degree of similarity differs by parameter and a single, uniform substitution strategy is not appropriate. Venous and arterial values are quite similar for pH and HCO3-, raw venous values for pCO2 are not consistently reliable on their own, and for pO2 deriving a dependable arterial estimate from venous data does not appear practical. We found an average arterial-venous pH difference of about 0.03 with a strong relationship; our formula reduced the mean difference below 0.01 and lowered the out-oflimit rate from 17%to7%. Published formulas (Ak, Khan, Kim) produced similar improvements, though the formula developed on our own dataset understandably performed slightly better [1,5,8,9]. Remaining within commonly cited acceptable difference limits (0.04-0.05) supports the use of venous pH aided by an adjustment [10-13]. For HCO3- the arterial-venous difference was small and clinically negligible, in line with prior reports [1,9,14], making venous measurement a practical option for initial metabolic assessment (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Scatter plots of venous versus arterial pH.

The situation is more problematic for pCO2. Although the mean arterial-venous difference fell within ranges reported in earlier studies [11-13], nearly half (≈48%) of raw venous pCO2 values lay outside acceptable error limits, weakening stand‑alone substitution. Our conversion formula reduced this proportion to 14%; other formulas also improved but to a lesser extent [5,8,9]. Variation in patient profiles and hypercapnia prevalence (e.g. 19-33% across series) can affect specificity, so broad external validation is needed before routine “replacement” claims are justified [11-13]. For pO2 the venous-arterial relationship was only moderate; modelling improved correlation, yet not to a clinically dependable level. Other studies likewise conclude venous pO2 and saturation do not reliably mirror arterial oxygenation [1,3,5,15]. Consequently, in scenarios where assessing hypoxemia is critical, arterial sampling remains necessary.

Overall, our results outline a three-tier picture: (1) pH and HCO3- : Venous values are generally suitable for most clinical contexts and become even more dependable with modest adjustments. (2) pCO2: Raw venous measurement is variable; conversion formulas reduce error but broad multicenter confirmation is required. (3) pO2: Current evidence does not support deriving clinically reliable arterial oxygen status from venous measurements. Superior performance of models built on our own dataset (notably for pH and pCO2) is expected and does not imply superiority until externally tested. Multicenter studies encompassing diverse patient groups (COPD exacerbation, sepsis, heart failure, ICU, emergency presentations) and different device types with adequate sample sizes are needed to determine generalizability of arterialization formulas. This study has several limitations. First, its single-center design and relatively small sample size limit the generalizability of the findings, particularly in patients with severe hypoxemia or hemodynamic instability. Second, as only one blood gas analyzer was employed, potential device-specific variability could not be assessed. Third, the conversion formulas were developed and validated using the same dataset, highlighting the need for external validation in broader and more diverse populations [16,17].

From telemedicine and AI Perspective, in the future, systematically accumulating both venous and arterial blood gas results-together with timestamp, primary diagnosis, oxygen/ ventilation support, key laboratory values, and clinical follow-up data-within secure digital platforms will be highly valuable. Large, well-structured data repositories can underpin development of AI-assisted, more accurate, patient-tailored prediction models. Practical tools could then estimate arterial values from venous measurements while transparently displaying error and uncertainty; this may reduce unnecessary arterial sampling, accelerate decision-making and strengthen remote monitoring for chronic conditions. Patient privacy, ethical approval, data security, continuous performance surveillance and timely model updates (e.g. when devices change) are critical safeguards. A stepwise buildout of such an ecosystem could enable broader, safer clinical use of venous blood gas analysis.

Conclusion

This prospective study indicates that simultaneously obtained venous blood gas samples can reflect arterial pH, pCO2 and HCO3⁻ with clinically acceptable agreement, whereas venous pO2 remains unreliable for estimating arterial oxygenation; thus, venous blood gas analysis may serve as a practical approach to reduce the need for invasive arterial puncture in serial monitoring of acid-base status and ventilation but cannot fully replace arterial sampling when precise assessment of hypoxemia or oxygenation is required. Mathematical conversion formulas from the literature provided only partial improvement in predicting arterial values and did not overcome the limitations related to oxygen parameters. The single-center design, limited sample size and underrepresentation of patients with severe hemodynamic instability constrain generalizability. Larger, multicenter studies integrating advanced predictive (including AI-based) models are warranted to refine venous-to-arterial estimation strategies.

AI Disclosure

AI-assisted tools were used only for language polishing/ translation and minor table formatting. No AI tool was used for data generation, statistical analysis, interpretation or drawing conclusions. The authors take full responsibility for the content.

References

- Bakoğlu E (2013) Investigation of the usability of peripheral venous blood gas as a replacement for arterial blood gas in the emergency department. Eur J Basic Med Sci 3(2): 29-33.

- Acican T (2003) Arterial blood gases. Intensive Care Journal 3: 160-175.

- Yildizdaş D, Yapicioğlu H, Yilmaz HL, Sertdemir Y (2004) Correlation of simultaneously obtained capillary, venous and arterial blood gases of patients in a paediatric intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child 89(2): 176-180.

- Boulain T, Garot D, Vignon P, Lascarrou JB, Dequinet PF, et al. (2016) Predicting arterial blood gas and lactate from central venous blood analysis in critically ill patients: A multicentre, prospective, diagnostic accuracy study. Br J Anaesth 117(3): 341-349.

- Ahmet Ak, Oztin CO, Aysegul B, Kayis SA, Ramazan K (2006) Prediction of arterial blood gas values from venous blood gas values in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Tohoku J Exp Med 210(4): 285-290.

- Lemoël F, Sandra G, Omri ME, Marquette CH, Jacques L (2013) Improving the validity of peripheral venous blood gas analysis as an estimate of arterial blood gas by correcting the venous values with SvO2. J Emerg Med 44(3): 709-716.

- United States Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA).

- Khan ZH, Mostafa S, Gholam AM, Poya ZA, Shahin AH, et al. (2010) Prospective study to determine possible correlation between arterial and venous blood gas values. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan 48(3): 136-139.

- Kim BR, Sae JP, Shin SH, Soon JY, Hark R, et al. (2013) Correlation between peripheral venous and arterial blood gas measurements in patients admitted to the intensive care unit: A single-center study. Kidney Res Clin Pract 32(1): 32-38.

- Rang LCF, Murray EH, George AW, Cameron KM (2002) Can peripheral venous blood gases replace arterial blood gases in emergency department patients? CJEM 4(1): 7-15.

- Peter MC, Kath B, Paul S, Geraldine MM (2012) Venous vs arterial blood gases in the assessment of patients presenting with an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Emerg Med 30(6): 896-900.

- Kelly AM, Klim S, Rees SE (2014) Agreement between mathematically arterialised venous versus arterial blood gas values in patients undergoing non-invasive ventilation: A cohort study. Emerg Med J 31(e1): e46-e49.

- Kelly AM, Kyle E, Ross MA (2002) Venous pCO2 and pH can be used to screen for significant hypercarbia in emergency patients with acute respiratory disease. J Emerg Med 22(1): 15-19.

- Middleton P, Kelly AM, Brown J, Robertson M (2006) Agreement between arterial and central venous values for pH, bicarbonate, base excess and lactate. Emerg Med J 23(8): 622-624.

- Gazları AK, Derleme AK (2007) Turkish Medical Journal 1: 44-50.

- Kelly AM, Ross MA, Kyle E (2004) Agreement between bicarbonate measured on arterial and venous blood gases. Emerg Med Australas 16(5-6): 407-409.

- Koul PA, Umar HK, Abdul AW, Rafiqa E, Rafi AJ, et al. (2011) Comparison and agreement between venous and arterial gas analysis in cardiopulmonary patients in Kashmir valley of the Indian subcontinent. Ann Thorac Med 6(1): 33-37.

© 2025 Erturk Zamir Kemal. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)