- Submissions

Full Text

Trends in Textile Engineering & Fashion Technology

Progress in Biopolymers in Textile Sciences: A Review

Mohammad Raza Miah1,2,3*, Ayub Nabi Khan1, Md. Abdul Jalil1 and Jin Zhu2

1Department of Textile Engineering, BGMEA University of Fashion and Technology (BUFT), Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Key Laboratory of Bio-based Polymeric Materials Technology and Application of Zhejiang Province, Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, People’s Republic of China

3University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, People’s Republic of China

*Corresponding author:Mohammad Raza Miah, Department of Textile Engineering, BGMEA University of Fashion and Technology (BUFT), Dhaka, 1230, Bangladesh

Submission: October 28, 2025;Published: December 10, 2025

ISSN 2578-0271 Volume11 Issue 3

Abstract

Biopolymers derived from renewable biomaterials have attracted widespread attention as sustainable alternatives to traditional synthetic polymers in textile applications. Their versatility spans fiber production, textile finishing, and functional coatings, in line with the growing demand for environmentally friendly materials and circular economy strategies. This summary explores the main classes of biopolymers including polysaccharides (e.g., cellulose, chitosan), proteins (e.g., silk, keratin), and polyesters (e.g., polylactic acid) and highlights their unique properties, such as biodegradability, biocompatibility, antimicrobial properties, and effective moisture control. Integrating biopolymers into textile production can reduce environmental impact and enable the creation of advanced, multifunctional textiles for medical, protective, and smart applications. The discussion also touches on current challenges, such as limited processability, mechanical properties, and scalability, as well as recent advances in material modification and composite material development. Finally, this review emphasizes the important role of biopolymers in driving sustainability and innovation in the textile industry.

Introduction

The growing demand for sustainable and environmentally friendly materials has had a significant impact on the textile industry, leading to a growing interest in the development and application of biopolymers [1,2]. Derived from renewable biological resources such as plants, animals, and microorganisms, biopolymers are environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional petroleum-based polymers [3,4]. Their inherent biodegradability, biocompatibility, and low toxicity make them ideal for a variety of textile applications, including fibers, coatings, composites, and functional finishes [5,6]. Moreover, recent advances have expanded the role of biopolymers from specialized uses to mainstream industrial applications [7]. Innovations in processing and chemical modification have improved their mechanical strength, thermal stability, and functional properties such as antimicrobial activity, UV resistance, and moisture management [8,9]. Key biopolymers such as polylactic acid (PLA), chitosan, alginates, starch, and cellulose derivatives are being actively explored to meet modern performance and sustainability needs [10,11]. Further, in textile production, biopolymers are used in a variety of forms, including fibers, films, coatings, and composites [12,13]. Regenerated cellulose fibers such as lyocell and viscose are valued in clothing for their softness, breathability, and moisture absorption [14]. Derived from renewable resources such as corn starch or sugar cane, PLA is increasingly used in fibers and nonwovens due to its compostability and mechanical strength [15,16]. Chitosan and alginate, known for their antimicrobial properties, are being developed for use in medical textiles and wound dressings, providing functionality beyond structural support [17,18]. Furthermore, beyond apparel, biopolymers are increasingly being used in technical textiles for biomedical, environmental, and agricultural applications [19,20]. Their tunable physicochemical properties and functional engineering capabilities (e.g., drug delivery, UV shielding, and pollutant absorption) make them promising materials for smart, sustainable textile systems [21,22].

Despite these advances, several challenges remain, including high production costs, limited thermal resistance, and inconsistent performance [23,24]. However, continued research into hybrid systems, nanocomposites, and environmentally friendly processing technologies is gradually addressing these limitations, paving the way for the next generation of high-performance, sustainable textiles [25,26]. The purpose of this review is to highlight the current status of biopolymer applications in textiles, examining the latest advances, processing technologies, implementation methods, and future directions for the circular and environmentally friendly textile industry [27].

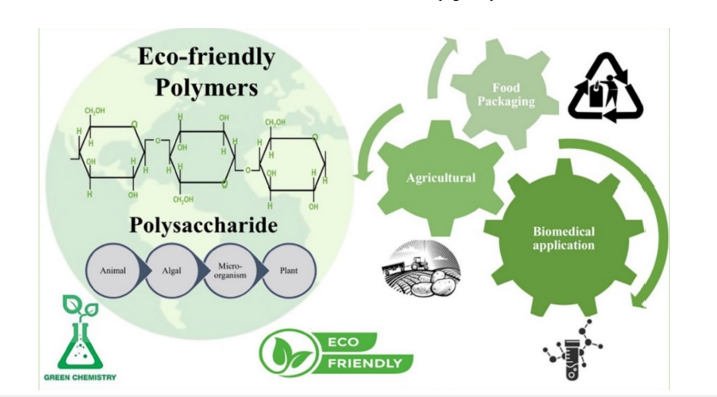

Polysaccharide-based biopolymers

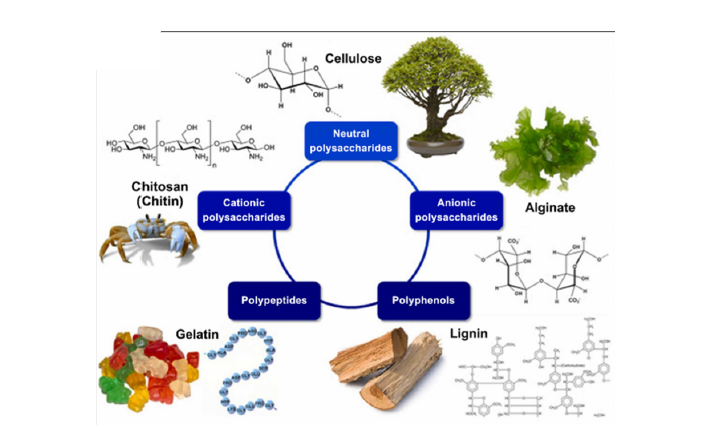

Polysaccharide-based biopolymers represent a class of naturally derived macromolecules composed of repeating monosaccharide units linked by glycosidic bonds [28]. These biopolymers are abundant, renewable, biodegradable, and exhibit diverse physicochemical properties, making them ideal candidates for a wide range of applications in biomedical, pharmaceutical, packaging, agricultural, and environmental fields [29,30]. Common examples include cellulose, chitosan, starch, alginate, agar, pectin, and dextran (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Polysaccharide-based materials as sustainable alternatives for biomedical, environmental, and food packaging, reproduced with permission from [30] Copyright © 2024 Elsevier B.V.

Cellulose: Cellulose, a natural polymer obtained from both plant and microbial sources, serves as a fundamental material in various textile and advanced material applications [31]. Plantderived cellulose- primarily from cotton and wood pulp- acts as the main raw material for producing regenerated fibers such as viscose, lyocell, and modal, which are extensively used in fashion and home textiles due to their softness, breathability, and sustainability [32]. Beyond traditional textiles, cellulose can be converted into nanocellulose, offering exceptional properties for use in functional coatings that provide water repellency, UV protection, and enhanced mechanical strength [33]. Additionally, bacterial cellulose, synthesized by certain bacterial strains, features a highly pure, nanoscale fibrous network. This unique structure makes it ideal for biomedical textiles, wound dressings, and highperformance composite materials where superior biocompatibility and mechanical integrity are essential [34].

Chitosan: Chitosan, a biopolymer derived from the deacetylation of chitin found in crustacean shells, has emerged as a versatile and sustainable material for textile and biomedical applications [35]. Its intrinsic biocompatibility, biodegradability, and antimicrobial properties make it particularly valuable in developing functional and eco-friendly textile products [36]. In the textile sector, chitosan is widely utilized in antimicrobial coatings for medical and hygiene textiles, providing effective protection against bacterial growth [37]. It also serves as a biodegradable finishing agent with additional wound healing benefits, enhancing the performance and comfort of healthcare fabrics. Moreover, chitosan is incorporated into fiber spinning blends, such as polylactic acid (PLA)/chitosan composites, to produce fibers with improved antimicrobial activity, moisture management, and overall functionality [38].

Starch: Starch, a natural polysaccharide obtained from renewable sources such as corn, potato, and rice, plays a significant role in sustainable textile processing and product development [39]. Owing to its biodegradability, abundance, and film-forming ability, starch is widely utilized across various stages of textile manufacturing. It serves as a sizing agent during yarn preparation, improving yarn strength and weavability while reducing breakage during weaving [40]. Beyond conventional processing, starch is increasingly blended with synthetic polymers to develop biodegradable textile fibers, promoting environmental sustainability in fiber production [41]. Additionally, chemically modified starch derivatives are employed in functional coatings to impart properties such as flame retardancy, breathability, and improved surface performance to textiles [6].

Alginate: Alginate, a natural polysaccharide extracted from seaweed particularly brown algae is highly valued for its biocompatibility, non-toxicity, and exceptional absorbency [42]. These properties make it an ideal material for medical and hygienerelated textile applications. In wound care, alginate is extensively used in the development of advanced dressings and medical textiles, where its ability to absorb exudates and maintain a moist healing environment promotes faster tissue regeneration [43]. Furthermore, alginate can be processed into fibers through wet spinning techniques, enabling its use in biomedical and hygiene textiles that require high absorbency, comfort, and biodegradability [44].

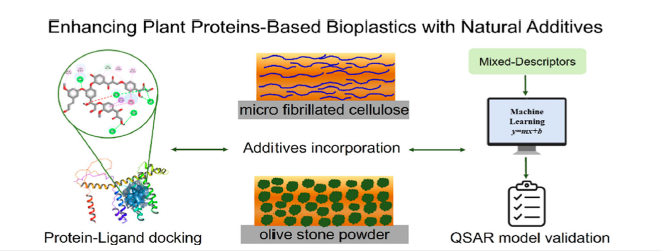

Protein-based biopolymers

Protein-based biopolymers are a class of natural or synthetic macromolecules derived from proteins or polypeptides [45]. These materials have attracted significant interest due to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, non-toxicity, and sustainable origins, making them promising candidates for applications in biomedical engineering, food packaging, agriculture, and environmentally friendly plastics [46,47] (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Enhancing plant protein-based bioplastics with natural additives, reproduced with permission from [47] Copyright © 2024 American Chemical Society.

Silk: Silk, a natural protein fiber produced by silkworms and spiders, is renowned for its exceptional luster, strength, and smooth texture, making it one of the most valued materials in the textile industry [48]. Traditionally, silk fibers have been used in high-end apparel and luxury textiles due to their aesthetic appeal, comfort, and durability. Beyond conventional applications, silk fibrointhe primary structural protein in silk- has gained significant attention in biomedical research [49]. Through techniques such as electrospinning, silk fibroin can be transformed into nanofibrous mats used in bioactive wound dressings and tissue engineering scaffolds, where its excellent biocompatibility, tunable degradation, and ability to support cell growth are highly advantageous [50].

Wool and keratin: Keratin, a fibrous structural protein obtained from natural sources such as sheep wool, feathers, and human or animal hair, is widely recognized for its strength, elasticity, and biocompatibility [51]. Traditionally, keratin-rich fibers like wool have been extensively used in textiles for clothing and insulation due to their excellent thermal properties, resilience, and comfort [52]. In recent years, keratin has gained increasing attention as a renewable biomaterial for advanced applications. Extracted and processed keratin can be incorporated into biocomposites and electrospun nanofibers, enabling the development of functional materials for cosmetic and medical textiles [53]. These keratinbased products offer benefits such as enhanced moisture retention, biocompatibility, and potential for wound healing and tissue regeneration.

Soy protein: Soy protein, derived as a byproduct of soybean processing, represents a sustainable and renewable source for developing eco-friendly textile materials [54]. Through regeneration and fiber-spinning processes, soy protein can be transformed into protein-based fibers that are fully biodegradable, soft, and skin-friendly [1]. These regenerated soy protein fibers are increasingly used in sustainable textiles, offering a silk-like feel and excellent moisture absorption. To enhance their mechanical strength and durability, soy protein fibers are often blended with natural or regenerated fibers such as cotton and viscose [55]. This combination results in fabrics that exhibit improved softness, breathability, and overall comfort, making them suitable for apparel and home textile applications.

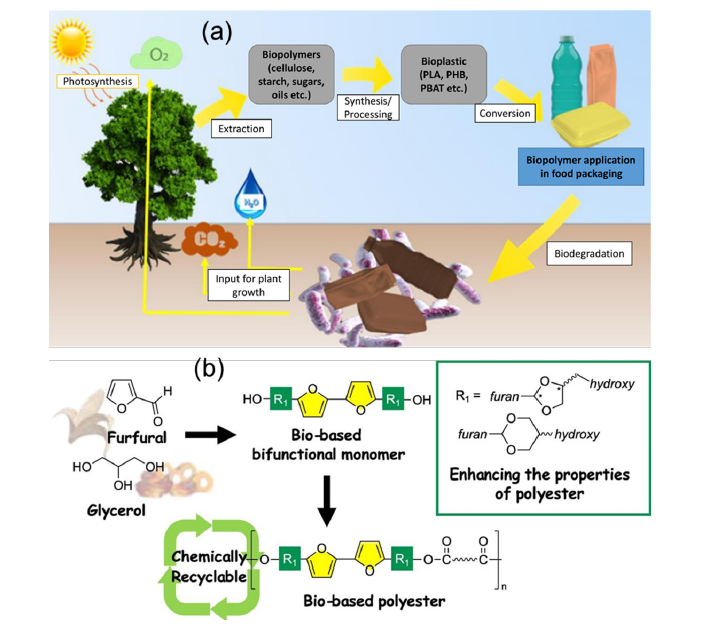

Polyester-based biopolymers

Polyester-based biopolymers are a class of biodegradable and/ or bio-based polymers characterized by ester linkages in their backbone structure [56]. These materials offer an environmentally friendly alternative to conventional petrochemical-derived plastics due to their degradability, renewability, and potential for sustainable production [57-59]. Their utility spans multiple sectors, including packaging, agriculture, biomedical devices, and textiles (Figure 3).

Figure 3:(a) Biopolymer-based sustainable food packaging applications, reproduced with permission from [58] Copyright © 2023 MDPI; (b) chemically recyclable bio-based polyester from bifuran and glycerol acetal, reproduced with permission from [59] Copyright © 2021 Elsevier B.V.

Polylactic acid (PLA): Polylactic acid (PLA) is biodegradable thermoplastic aliphatic polyester derived primarily from renewable resources such as corn starch, sugarcane, or cassava [60]. Its ecofriendly origin, coupled with favorable mechanical and physical properties, has led to growing interest in PLA as a sustainable alternative to petroleum-based synthetic fibers in the textile industry [61,62].

Synthesis and properties: PLA is synthesized through the polymerization of lactic acid via either direct condensation or ring-opening polymerization of lactide [63]. The resulting polymer exhibits a semi-crystalline structure with tunable properties depending on molecular weight and stereochemistry. PLA fibers offer good tensile strength, low flammability, and high UV resistance, making them suitable for a wide range of textile applications [64]. However, its relatively low thermal stability and brittleness can limit its performance in high-stress or high-temperature environments.

Fiber spinning and fabrication: PLA can be processed using conventional melt spinning, solution spinning, or electrospinning techniques [65]. These methods enable the production of fine, continuous filaments that can be woven, knitted, or nonwoven into fabrics. Blending PLA with other natural or synthetic polymers, such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) or polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs), is often employed to enhance flexibility and durability [66].

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA)

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are a class of biopolyesters produced by various microorganisms through the fermentation of carbon-rich substrates such as sugars, vegetable oils, or waste biomass [67]. PHAs are fully biodegradable and biocompatible, making them promising candidates for sustainable textile applications. Unlike polylactic acid (PLA), PHAs are synthesized intracellularly by microbial processes and possess a wide range of material properties depending on their monomer composition, such as polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and polyhydroxyvalerate (PHV) [68,69].

Synthesis and material properties: PHAs are typically biosynthesized under nutrient-limited conditions in the presence of excess carbon sources. The resulting biopolyesters can vary in crystallinity, melting temperature, and mechanical behaviour [70]. For textile applications, PHAs offer the advantages of moderate tensile strength, UV resistance, and resistance to hydrolytic degradation, while being readily compostable [71]. However, PHBthe most common form- tends to be brittle, which can limit its standalone application in textiles unless modified or blended.

Processing for textile applications: PHA can be processed into fibers using melt spinning, solution spinning, and electrospinning. Electrospun PHA nanofibers are particularly attractive for biomedical and filtration textiles due to their high surface-areato- volume ratio and porosity [72]. Blending with other polymers such as PLA, thermoplastic starch, or elastomers, or incorporating plasticizers, can improve flexibility and elongation at break, enhancing their processability and performance in textile forms [73].

Other emerging biopolymers

Emerging biopolymers such as lignin and gelatin have attracted growing interest due to their abundance, renewability, and functional versatility [74]. Unlike conventional biopolymers like cellulose or starch, these materials offer unique chemical compositions and properties that enable novel applications in diverse fields, from biomedicine to sustainable packaging [75,76] (Figure 4).

Figure 4:Natural biopolymers with microbial encapsulation potential, reproduced with permission from [76] copyright © 2019 NotionWave Inc.

Lignin: Lignin, a highly aromatic and complex biopolymer, is the second most abundant natural polymer on Earth after cellulose. It is primarily obtained as a by-product from the pulp and paper industry [77]. Lignin’s polyphenolic structure offers intrinsic antioxidant, antimicrobial, and UV-absorbing properties, making it a promising candidate for functional materials in packaging, adhesives, and composites [78]. Recent advances in lignin valorization focus on chemical modification and nanoparticle formulation to improve its compatibility with polymers and expand its utility in high-value applications, such as carbon fibers, 3D printing resins, and biosensors [79].

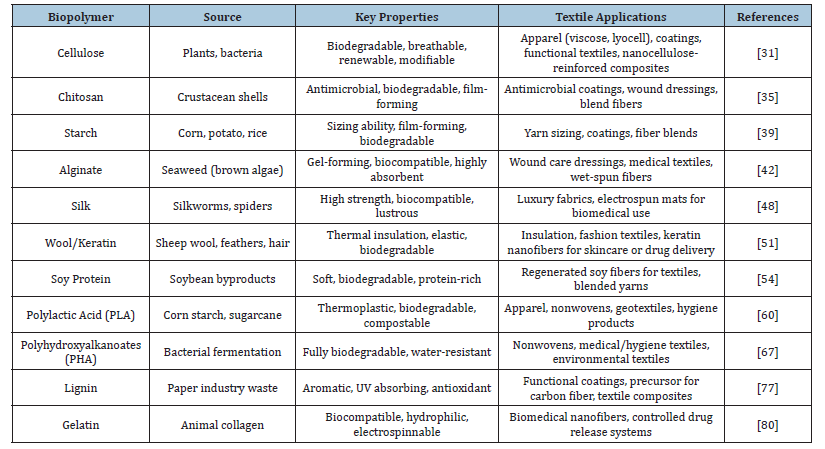

Gelatin: Gelatin, a protein-based biopolymer derived from collagen, is widely utilized for its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and gel-forming ability [80]. It finds applications in pharmaceuticals, food, cosmetics, and biomedical engineering. In tissue engineering, gelatin serves as a scaffold material due to its ability to mimic the extracellular matrix [81]. Its ability to be easily cross-linked and modified chemically allows for the development of hydrogels, drug delivery systems, and wound dressings with tunable properties. Together, these emerging biopolymers offer sustainable alternatives to petroleum-derived polymers and are central to developing the next generation of bio-based functional materials [16]. Challenges remain in processing, performance optimization, and economic scalability, but ongoing research continues to broaden their application landscape through innovative modifications and hybrid composite strategies [82] (Table 1).

Table 1:Summary of biopolymers in textile applications.

Current Research and Innovations

Current research and innovations in biopolymer-based textiles are focused on advancing material performance, functionality, and sustainability through interdisciplinary approaches [83]. Biopolymer blends are being developed to improve processability, mechanical strength, and durability, enabling wider applicability in textile manufacturing. Nanotechnology plays a pivotal role by incorporating functional nanoparticles such as ZnO and TiO₂ into biopolymer matrices, imparting properties like UV protection, antimicrobial activity, and electrical conductivity [83]. The emergence of smart textiles further expands the scope of biopolymer applications, where biocompatible matrices are integrated with sensors, actuators, or stimuli-responsive materials to create interactive and adaptive fabrics. Moreover, waste valorization has become a key research focus, transforming agricultural and food industry byproducts- such as orange peels and milk proteins- into novel biopolymers, thereby promoting circular economy principles and reducing environmental impact within the textile sector [83].

Conclusion

The integration of biopolymers with textile science represents a significant advance in the development of sustainable and environmentally friendly materials. Derived from renewable bioresources, biopolymers such as polylactic acid (PLA), chitosan, alginate, and starch-based polymers offer promising alternatives to conventional petrochemical fibers. Their applications span functional textiles, biodegradable fabrics, medical textiles, and smart clothing, with additional benefits such as biocompatibility, antimicrobial activity, and environmental degradation. Despite current challenges such as mechanical limitations, processing restrictions, and cost considerations, ongoing advances in polymer modification and composite material development continue to improve their performance. As the textile industry strives to achieve global sustainability goals, biopolymers will play a transformative role in the development of next-generation textiles with minimal environmental impact.

References

- Patti A, Acierno D (2022) Towards the sustainability of the plastic industry through biopolymers: Properties and potential applications to the textiles world. Polymers 14(4): 692.

- Miah MR, Dong Y, Wang J, Zhu J (2024) Recent progress on sustainable 2, 5-furandicarboxylate-based polyesters: Properties and applications. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 12(8): 2927-2961.

- Dias JC, Marques S, Branco PC, Rodrigues T, Torres CA, et al. (2025) Biopolymers derived from forest biomass for the sustainable textile industry. Forests 16(1): 163.

- Miah MR, Ding J, Zhao H, Chu Q, Wang H, et al. (2025) Enhancement of mechanical, thermal, and barrier behavior of sustainable PECF copolyester nanocomposite films using polydopamine-functionalized MXene fillers. Langmuir 41(15): 9680-9691.

- Khaleel G, Sharanagat VS, Upadhyay S, Desai S, Kumar K, et al. (2025) Sustainable approach toward biodegradable packaging through naturally derived biopolymers: An overview. Journal of Packaging Technology and Research 9(1): 19-46.

- Ghosh J, Rupanty NS, Noor T, Asif TR, Islam T, et al. (2025) Functional coatings for textiles: advancements in flame resistance, antimicrobial defense, and self-cleaning performance. RSC Advances 15(14): 10984-11022.

- Sharif NU, Habibu S, Wang H, Veera Singham G, Huang HK, et al. (2025) Advancing renewable functional coatings: Sustainable solutions for modern material challenges. Journal of Coatings Technology and Research pp: 1-27.

- Polaki S, Mereddy S, Ramya K, Mohanbabu C, Kumar MA (2026) Recent progress and future perspectives of biopolymer-based composites for energy storage and generation. Biopolymer-based Composites for Energy Generation and Storage pp: 49-79.

- Huang C, Qin Q, Liu Y, Duan G, Xiao P, et al. (2025) Physicochemical, polymeric and microbial modifications of wood toward advanced functional applications: A review. Chemical Society Reviews 54: 9027-9091.

- Periyasamy T, Asrafali SP, Lee J (2025) Recent advances in functional biopolymer films with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties for enhanced food packaging. Polymers 17(9): 1257.

- Maitra J, Bhardwaj N (2025) Development of bio-based polymeric blends–a comprehensive review. Journal of Biomaterials Science Polymer Edition 36(1): 102-136.

- Selvam T, Rahman NMMA, Olivito F, Ilham Z, Ahmad R, et al. (2025) Agricultural waste-derived biopolymers for sustainable food packaging: Challenges and future prospects. Polymers 17(14): 1897.

- Miah MR, Wang J, Zhu J (2025) Introduction: Green materials and sustainability in active food packaging. In: Green Materials for Active Food Packaging, Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, pp: 1-33.

- Alzahrani AS, Alamry KA, Hussein MA (2025) Advanced biopolymer nanocomposites for real-time biosurveillance and defense against antimicrobial resistance and viral threats. RSC Advances 15(39): 32431-32463.

- Miah MR, Ding J, Zhao H, Wang H, Chu Q, et al. (2024) Enhancing the mechanical and barrier properties of biobased polyester incorporated with carboxylated cellulose nanofibers. Materials Today Communications 38: 108538.

- Rajendran S, Al‐Samydai A, Palani G, Trilaksana H, Sathish T, et al. (2025) Replacement of petroleum based products with plant-based materials, green and sustainable energy-A review. Engineering Reports 7(4): e70108.

- Miah MR, Ding J, Zhao H, Chu Q, Wang H, et al. (2024) Boron nitride-based polyester nanocomposite films with enhanced barrier and mechanical performances. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 6(5): 2913-2923.

- Ding J, Wang H, Zhao H, Shi S, Su J, et al. (2024) Large-size ultrathin mica nanosheets: Reinforcements of biobased PEF polyester. Giant 18: 100264.

- Wang H, Ding J, Zhao H, Chu Q, Miah MR, et al. (2024) Preparing strong, tough, and high-barrier biobased polyester composites by regulating interfaces of carbon nanotubes. Materials Today Nano 25: 100463.

- Ding J, Zhao H, Shi S, Su J, Chu Q, et al. (2024) High‐strength, high‐barrier bio‐based polyester nanocomposite films by binary multiscale boron nitride nanosheets. Advanced Functional Materials 34(1): 2308631.

- Taher MA, Wang X, Faridul Hasan KM, Miah MR, Zhu J, et al. (2023) Lignin modification for enhanced performance of polymer composites. ACS Applied Bio Materials 6(12): 5169-5192.

- Miah MR, Wang J, Zhu J (2024) Material advancements in plant/artificial fiber-based woven and non-woven fabrics and their composites. In: Innovations in Woven and Non-woven Fabrics Based Laminated Composites, Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, pp: 17-50

- Miah MR, Mahmud S, Khan AN, Jalil MA, Wang J, et al. (2025) Recent advances in sustainable thermoplastic polyester Elastomers: Synthesis, properties and applications. Polymer 336: 128878.

- Yan Q, Kanatzidis MG (2022) High-performance thermoelectrics and challenges for practical devices. Nature Materials 21(5): 503-513.

- Anik HR, Tushar SI, Mahmud S, Khadem AH, Sen P, et al. (2025) Into the revolution of nanofusion: Merging high performance and aesthetics by nanomaterials in textile finishes. Advanced Materials Interfaces 12(1): 2400368.

- Syduzzaman M, Hassan A, Anik HR, Akter M, Islam MR (2023) Nanotechnology for high‐performance textiles: A promising frontier for innovation. ChemNanoMat 9(9): e202300205.

- Jabeen N, Atif M (2024) Polysaccharides based biopolymers for biomedical applications: A review. Polymers for Advanced Technologies 35(1): e6203.

- George A, Sanjay MR, Srisuk R, Parameswaranpillai J, Siengchin S (2020) A comprehensive review on chemical properties and applications of biopolymers and their composites. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 154: 329-338.

- Behrooznia Z, Nourmohammadi J (2024) Polysaccharide-based materials as an eco-friendly alternative in biomedical, environmental, and food packaging. Giant 19: 100301.

- Shaghaleh H, Xu X, Wang S (2018) Current progress in production of biopolymeric materials based on cellulose, cellulose nanofibers, and cellulose derivatives. RSC Advances 8(2): 825-842.

- Atalie D, Abtew MA, Zhao L (2025) Recent advances in bio-based nonwoven materials: Sustainable production, applications, and circular economy. Journal of Natural Fibers 22(1): 2565661.

- Spagnuolo L, D'Orsi R, Operamolla A (2022) Nanocellulose for paper and textile coating: The importance of surface chemistry. ChemPlusChem 87(8): e202200204.

- Gorgieva S (2020) Bacterial cellulose as a versatile platform for research and development of biomedical materials. Processes 8(5): 624.

- Merzendorfer H, Cohen E (2019) Chitin/chitosan: Versatile ecological, industrial, and biomedical applications. In: Cohen E, Merzendorfer H (Eds.), Extracellular Sugar-Based Biopolymers Matrices, Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp: 541-624.

- Hossain MM, Islam T, Jalil MA, Rakibuzzaman SM, Surid SM, et al. (2024) Advancements of eco‐friendly natural antimicrobial agents and their transformative role in sustainable textiles. SPE Polymers 5(3): 241-276.

- Rahman Bhuiyan MA, Hossain MA, Zakaria M, Islam MN, Zulhash Uddin M (2017) Chitosan coated cotton fiber: Physical and antimicrobial properties for apparel use. Journal of Polymers and the Environment 25(2): 334-342.

- Ilyas RA, Aisyah HA, Nordin AH, Ngadi N, Zuhri MYM, et al. (2022) Natural-fiber-reinforced chitosan, chitosan blends and their nanocomposites for various advanced applications. Polymers 14(5): 874.

- Khoo PS, Ilyas RA, Uda MNA, Hassan SA, Nordin AH, et al. (2023) Starch-based polymer materials as advanced adsorbents for sustainable water treatment: Current status, challenges, and future perspectives. Polymers 15(14): 3114.

- Sahoo SK, Dash BP, Khandual A (2025) Sustainable yarn sizing process. In: Advancements in Textile Finishing: Techniques, Technologies, and Trends, Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore, pp: 47-74.

- Temesgen S, Rennert M, Tesfaye T, Nase M (2021) Review on spinning of biopolymer fibers from starch. Polymers 13(7): 1121.

- Alfinaikh RS, Alamry KA, Hussein MA (2025) Sustainable and biocompatible hybrid materials-based sulfated polysaccharides for biomedical applications: A review. RSC advances 15(6): 4708-4767.

- Sahay SS, Sharma P, Dave V (2024) Nanotechnology and biomaterials for hygiene and healthcare textiles. In: Nanotechnology Based Advanced Medical Textiles and Biotextiles for Healthcare, CRC Press, pp: 43-72.

- Qosim N, Dai Y, Williams GR, Edirisinghe M (2024) Structure, properties, forming, and applications of alginate fibers: A review. International Materials Reviews 69(5-6): 309-333.

- Nagarajan S, Radhakrishnan S, Kalkura SN, Balme S, Miele P, et al. (2019) Overview of protein‐based biopolymers for biomedical application. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 220(14): 1900126.

- Aziz T, Ullah A, Ali A, Shabeer M, Shah MN, et al. (2022) Manufactures of bio‐degradable and bio‐based polymers for bio‐materials in the pharmaceutical field. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 139(29): e52624.

- Shevtsova T, Iduoku K, Patnode Setien K, Olabode I, Casanola-Martin GM, et al. (2024) Enhancing plant protein-based bioplastics with natural additives: A comprehensive study by experimental and computational approaches. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering12(43): 15948-15960.

- Babu KM (2015) Natural textile fibres: Animal and silk fibres. In: Textiles and fashion, Woodhead Publishing, pp: 57-78.

- Lujerdean C, Baci GM, Cucu AA, Dezmirean DS (2022) The contribution of silk fibroin in biomedical engineering. Insects 13(3): 286.

- Aldahish A, Shanmugasundaram N, Vasudevan R, Alqahtani T, Alqahtani S, et al. (2024) Silk fibroin nanofibers: Advancements in bioactive dressings through electrospinning technology for diabetic wound healing. Pharmaceuticals 17(10): 1305.

- Giteru SG, Ramsey DH, Hou Y, Cong L, Mohan A, et al. (2023) Wool keratin as a novel alternative protein: A comprehensive review of extraction, purification, nutrition, safety, and food applications. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 22(1): 643-687.

- Ma YS, Kuo FM, Liu TH, Lin YT, Yu J, et al. (2024) Exploring keratin composition variability for sustainable thermal insulator design. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 275(Pt 2): 133690.

- Wang Z, Xiao N, Guo S, Liu X, Liu C, et al. (2024) Unlocking the potential of keratin: A comprehensive exploration from extraction and structural properties to cross-disciplinary applications. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 73(2): 1014-1037.

- Tahir M, Li A, Moore M, Ford E, Theyson T, et al. (2024) Development of eco-friendly soy protein fiber: A comprehensive critical review and prospects. Fibers 12(4): 31.

- Periyasamy AP, Militky J (2020) Sustainability in regenerated textile fibers. In: Sustainability in the Textile and Apparel Industries: Sourcing Synthetic and Novel Alternative Raw Materials, Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp: 63-95.

- Satti SM, Shah AA (2020) Polyester‐based biodegradable plastics: An approach towards sustainable development. Letters in Applied Microbiology 70(6): 413-430.

- Hayes G, Laurel M, MacKinnon D, Zhao T, Houck HA, et al. (2022) Polymers without petrochemicals: sustainable routes to conventional monomers. Chemical Reviews 123(5): 2609-2734.

- Perera KY, Jaiswal AK, Jaiswal S (2023) Biopolymer-based sustainable food packaging materials: Challenges, solutions, and applications. Foods 12(12): 2422.

- Hayashi S, Tachibana Y, Tabata N, Kasuya KI (2021) Chemically recyclable bio-based polyester composed of bifuran and glycerol acetal. European Polymer Journal 145: 110242.

- Fatchurrohman N, Muhida R, Maidawati (2023) From corn to cassava: Unveiling PLA origins for sustainable 3D printing. Journal Teknologi 13(2): 87-93.

- Taib NAAB, Rahman MR, Huda D, Kuok KK, Hamdan S, et al. (2023) A review on poly lactic acid (PLA) as a biodegradable polymer. Polymer Bulletin 80(2): 1179-1213.

- Mayilswamy N, Kandasubramanian B (2022) Green composites prepared from soy protein, polylactic acid (PLA), starch, cellulose, chitin: A review. Emergent Materials 5(3): 727-753.

- Montané X, Montornes JM, Nogalska A, Olkiewicz M, Giamberini M, et al. (2020) Synthesis and synthetic mechanism of Polylactic acid. Physical Sciences Reviews 5(12): 20190102.

- Yang Y, Zhang M, Ju Z, Tam PY, Hua T, et al. (2021) Poly (lactic acid) fibers, yarns and fabrics: Manufacturing, properties and applications. Textile Research Journal 91(13-14): 1641-1669.

- Zhang LH, Duan XP, Yan X, Yu M, Ning X, et al. (2016) Recent advances in melt electrospinning. RSC Advances 6(58): 53400-53414.

- Naser AZ, Deiab I, Defersha F, Yang S (2021) Expanding poly (lactic acid) (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) applications: A review on modifications and effects. Polymers 13(23): 4271.

- Koller M (2018) A review on established and emerging fermentation schemes for microbial production of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biopolyesters. Fermentation 4(2): 30.

- Meereboer KW, Misra M, Mohanty AK (2020) Review of recent advances in the biodegradability of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) bioplastics and their composites. Green Chemistry 22(17): 5519-5558.

- Anitha NNN, Srivastava RK (2021) Microbial synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and their applications. Environmental and Agricultural Microbiology: Applications for Sustainability pp: 151-181.

- Koller M, Mukherjee A (2022) Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs)-production, properties, and biodegradation. Biodegradable Polymers in the Circular Plastics Economy pp: 145-204.

- Andrzejewski J, Das S, Lipik V, Mohanty AK, Misra M, et al. (2024) The development of poly (lactic acid) (PLA)-based blends and modification strategies: Methods of improving key properties towards technical applications. Materials 17(18): 4556.

- Vasile C, Baican M (2023) Lignins as promising renewable biopolymers and bioactive compounds for high-performance materials. Polymers 15(15): 3177.

- Baranwal J, Barse B, Fais A, Delogu GL, Kumar A (2022) Biopolymer: A sustainable material for food and medical applications. Polymers 14(5): 983.

- Dutta D, Sit N (2024) A comprehensive review on types and properties of biopolymers as sustainable bio‐based alternatives for packaging. Food Biomacromolecules 1(2): 58-87.

- Hassan MES, Bai J, Dou DQ (2019) Biopolymers; definition, classification and applications. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry 62(9): 1725-1737.

- Bajwa DS, Pourhashem G, Ullah AH, Bajwa SG (2019) A concise review of current lignin production, applications, products and their environmental impact. Industrial Crops and Products 139: 111526.

- Zhang Y, Naebe M (2021) Lignin: A review on structure, properties, and applications as a light-colored UV absorber. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 9(4): 1427-1442.

- Shorey R, Salaghi A, Fatehi P, Mekonnen TH (2024) Valorization of lignin for advanced material applications: A review. RSC Sustainability 2(4): 804-831.

- Salleh KM, Armir NAZ, Mazlan NSN, Wang C, Zakaria S (2021) 2.1 Overview of cellulose fibres.

- He Y, Wang C, Wang C, Xiao Y, Lin W (2021) An overview on collagen and gelatin-based cryogels: Fabrication, classification, properties and biomedical applications. Polymers 13(14): 2299.

- Echave MC, del Burgo LS, Pedraz JL, Orive G (2017) Gelatin as biomaterial for tissue engineering. Current Pharmaceutical Design 23(24): 3567-3584.

- Li C, Wu J, Shi H, Xia Z, Sahoo JK, et al. (2022) Fiber‐based biopolymer processing as a route toward sustainability. Advanced Materials 34(1): e2105196.

- Baishya H, Dutta J, Kumar S (2025) Nanofillers reinforcing biopolymer composites for sustainable food packaging applications: A state‐of‐the‐art review. Advanced Functional Materials 35(47): 2503819.

- Socas-Rodríguez B, Álvarez-Rivera G, Valdés A, Ibáñez E, Cifuentes A (2021) Food by-products and food wastes: Are they safe enough for their valorization? Trends in Food Science & Technology 114: 133-147.

© 2025 Mohammad Raza Miah. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)