- Submissions

Full Text

Significances of Bioengineering & Biosciences

Nutritional Status and Feeding Habits of Players in a Professional Soccer Team

José Antonio Pareja Esteban, Mónica Sánchez Santiuste*, Marta García López, Ana Collantes Casanova and Víctor Vaquerizo García

Prince of Asturias University Hospital, Spain

*Corresponding author:Mónica Sánchez Santiuste, Prince of Asturias University Hospital, Madrid, Spain

Submission: December 1, 2025; Published: December 22, 2025

ISSN 2637-8078Volume7 Issue 5

Abstract

Despite soccer being the most popular sport on the planet, player nutrition is certainly a neglected aspect of their preparation. Physical activity requires a mix of the different physiological mechanisms of energy production, both aerobic and anaerobic and therefore a balanced intake of nutrients. The role of carbohydrates is widely known to be a key aspect of athletic performance.

Objective: To determine the nutritional habits and intake of macronutrients of soccer players in a single professional team.

Materials and Methods: We carried out an epidemiological, descriptive, prospective study including the 22 male players on a single Spanish second-division B soccer team. The average age was 26.19 years old (19.5-31.6). We ellaborated a protocol for data collection regarding nutritional intake for 7 consecutive days, measuring macronutrient intake and quantifying total energy expenditure, which varied depending on training sessions and player position.

Results: On average, carbohydrate consumption was 305.0756gr (48.78% of calories consumed). There were statistically significant differences between carbohydrate consumption on moderate-intensity activity days (on average 213.637gr; 39.93% of total intake) and high-intensity activity days (on average 361.8428gr; 49.21% of total intake). In addition, we found significant differences in player height, base metabollic rate and total energy expenditure between the positions of goalkeeper and advanced band player (p<0.05).

Discussion: Both the average carbohydrate intake and the overall caloric intake of our athletes fell short of the recommended standard for professional soccer players (3,600Kcal/day).

Introduction

Soccer has become a cultural and media phenomenon practiced by over 265 million people worldwide, according to FIFA statistics from 2006. In 2022, over 3.4 million spectators watched the FIFA World Cup live in Qatar, with 5 billion spectators in total media engagement [1]. Due to increasing demand and competition, ways of improving player performance are continuously under investigation. The last few decades have seen great advances in the study of player anthropometry, physiological development and energetic requirements during training and matches [2-4]. Soccer is a seasonal team sport, hence physical requirements are highly variable both in the long and short term. During training and match season there is an almost daily combination of moderate (jogging, pacing…) and high-intensity activity (sprinting, direction changes, jumping, charging…) [5]. Due to rapid shifts between aerobic and anaerobic energy production, a sufficient and balanced intake of both macro and micronutrients is essential. Nutrition is key in an athelete’s professional and personal life and official guidelines have been released regarding the ideal nutritional and feeding habits for professional soccer players [6,7]. Inadequate nutrition has been amply linked to:

A. A decrease in player performance and an increase in injuries [8,9].

B. Metabolic, reproductive, hormonal and immunological imbalances [10,11].

C. An increase in body fat and lower muscle mass [4].

A soccer player’s diet must be meticulously planned in advance in order to rebuild an adequate nutritional stock in the 4-7 days between matches and to ensure optimal performance during training sessions [4]. This study will focus on the analysis of macronutrients in soccer players’ diets: Carbohydrates (CH), Lypids (LP) and Proteins (PT). Studies have repeatedly shown glycogen muscle-concentration before, during and after physical activity is a key factor in athletic performance. High CH intake lessens muscle fatigue and improves execution (greater intensity during disputes, more ground covered during matches, even better technique) [12- 16]. The recommended daily CH intake is 5-7gr/Kg on moderateintensity activity days and 7-10gr/Kg on high-intensity activity days where muscle-glycogen depletion is achieved [4]. In fact, the rebuilding of glycogen muscle-reserves has been shown to be more efficient after early CH intake (1-1.2gr/Kg) in the first hour following physical activity [17,18] particularly with foods with a high glycemic index [14]. Protein requirements, however, have not been as throughly studied. Lemond [19] suggests an optimal daily intake of 1.4-1.7gr/Kg based on strength and resistance studies. It appears PT intake shortly before physical activity provides a positive nitrogen balance in the active muscle, allowing it to better meet the physical requirements of training or competing [9]. With respect to lypids, it is recommended they not exceed 30% of total nutrient intake. In soccer, most of the energetic supply comes from aerobic respiration, which means fats undergo oxidation in between bouts of intense physical activity but are not the main source of energy during active competition [2].

Hence, the need for strict regulation of athletes’ nutritional habits becomes apparent. However, most studies conclude the overall caloric intake of professional soccer players, particularly in the way of carbohydrates, falls short of the recommended standards [1,2,4,7,12,16,20-22].

Objectives

The objective of this study is to determine the nutritional habits of soccer players in a single professional team. We hypothesise we will find a deficient macronutrient intake in our sample as whole with respect to average energy expenditure and to the standards recommended in other studies and guidelines.

Materials and Methods

Sample selection

An epidemiological, descriptive, prospective study was carried out in a sample comprised of 22 male players, on average 26.19 years old (19.5-31.6), on a single Spanish second-division B soccer team. We ensured said players did not perform any other physical activity outside of their professional schedule in order to mimise bias during data collection. All players and their technical team were informed of the characteristics and aims of the study and guaranted anonyminity and data protection whereby findings would not influence their participation or position on the team. Informed consent was given by each subject and all them adhered to and completed protocol and follow-up./p>

Methodology

We ellaborated a protocol for data collection regarding each player’s complete nutritional intake for 7 consecutive days (Friday to Friday) in the month of February, around the fourth matchday of the second round, where our team was the visiting team, so all meals on Sunday were approved by the home team’s medical staff. Each player was highly encouraged not to alter their regular feeding habits during the study and each of them was given a questionnaire to fill out after every meal. Macronutrient intake was calculated either through direct measurement by weighing the ingredient or indirectly using product information on pre-cooked cans and containers. Cooking technique was also specified (raw, boiled, roasted, raw, fried…).

Supplements and micronutrients were not quantified during this study

After each meal, data was then digitalised and anylysed using the application “Mi dietario V.5.0”, which easily allows you to divide food into the different food groups (dairy, plant-based, meats…), select the precise ingredient, its weight and calculates macronutrient intake per player per day (CH, LP and PT). A basic anthropometric analysis was carried out for each participant at the beginning of the study. Height and weight were recorded using the same approved Seca® model 713 scale; Body Mass Index (BMI), percentage of lean mass and body fat were calculated. Body fat was calculated non-invasively through the Durnin and Womersley formula [23] using bicipital, tricipital, subscapular and suprailiac skinfold thickness. Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR) was calculated using the original Harris-Benedict formula [24] which was then modified by Mifflin MD, et al. [25]. Quantifying total energy expenditure took into account BMR, 10% thermogenesis rate and estimated expenditure in relation to physical activity (dietary reference in takes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids, 2002). The evolution of soccer training methods implies physical activity throughout the week does not follow a repetitive pattern, but rather a dynamic one with frequent variations in physical demand and excercises.

The week was subdivided into moderate, high and very highintensity activity days. Days 1 and 2 were high-activity days involving tactical training and goal scoring; days 4 and 5 were moderate-activity days of rest and recovery; days 3, 6 and 7 were very-high-activity days involving match day, simulation matches and double training sessions.

Nutritional demand therefore varies throughout the week

Player position was also taken into consideration, as physical requirements vary greatly between standard-mobility (goalkeeper, centre-back or striker) and high-mobility players (central midfielder, wing-back, winger). Data was collected and analysed using IBM®-SPSS Statistics 20 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago Ill., USA). Statistical significance was established at p≤0.05. Since sample size was <50, Shapiro Wilk’s test was used to determine whether our population and each subgroup were normally distributed. For parametric distribution we used student’s t-distribution and ANOVA; for non-parametric distribution we used Mann-Whitney’s U and Kruskall-Wallis tests. A post hoc test was performed after a significant overall result was obtained to determine which specific groups had a significant difference between their means.

Results

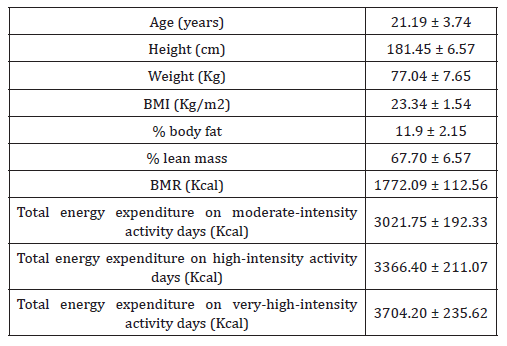

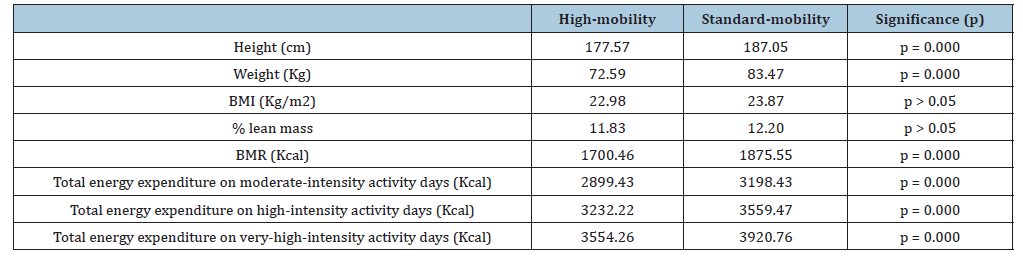

Table 1 shows the average results of our anthropometric analysis at the beginning of the study (from top to bottom: Age, height (cm), weight (Kg), BMI (Kg/m), body fat %, lean mass %) and calculated energy expenditure for the week based on (from top to bottom) BMR (1772.09112.56Kcal), total energy expenditure on moderate-intensity activity days (3021.75192.33Kcal), total energy expenditure on high-intensity activity days (3366.40211.07Kcal) and total energy expenditure on veryhigh- intensity activity days (3704.20235.62Kcal). In Table 2 we compared results between the two different mobility groups: Standard (goalkeeper, centre-back or striker) and high-mobility players (central midfielder, wing-back, winger). From top to bottom we compared weight, heigh, BMI, body fat %, lean mass %, energy expenditure on moderate-intensity activity days, energy expenditure on high-intensity activity days, energy expenditure on very-high-intensity activity days. Interestingly, standard-mobility players were significantly taller and heavier (187.05 vs 177.57cm; 83.47 vs 72.59Kg) and high-mobility players (p=0.000). Average BMI and body fat percentage were also higher among standardmobility players, but no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups (p>0.05). BMR and total energy expenditure was also significantly greater on any given day for standard-mobility players (p=0.000).

Table 1: Average demographic data.

Table 2: Comparing data for high-mobility vs standard-mobility players.

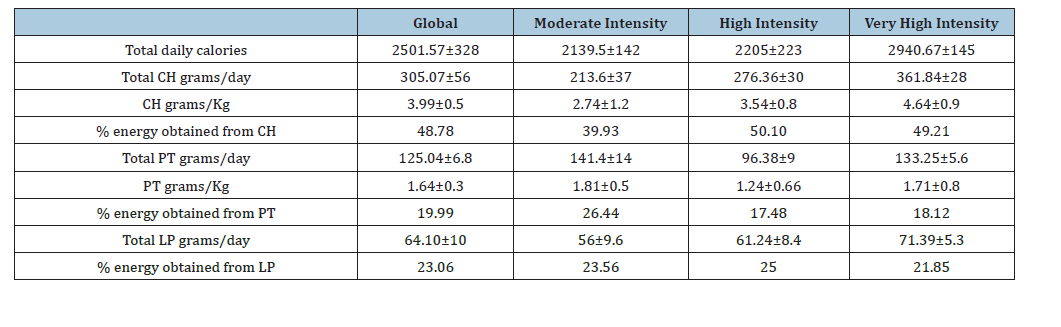

It is likely the greater energetic and nutritional requirements of standard-mobility players (central midfielder, wing-back, winger) than their high-mobility counterparts stem from the basal anthropometric differences between them in weight, height and BMR (1875.55 vs 1700.46Kcal). When analyzing each player position individually, we only found statistically significant differences (p<0.05) in height (189 vs 175cm), BMR (1899 vs 1678Kcal) and total energy expenditure on days of moderate, high and very-high-intensity activity (3238 vs 2861Kcal/day; 3603 vs 3184Kcal/day, 3969 vs 3507Kcal/day, respectively) between goalkeepers and wingers. On average, strikers presented greater BMIs (25.6Kg/m2) and weight (87.5Kg) than other players, with no statistically significant difference (p=0.05). Table 3 quantifies our findings with respect to the players’ nutritional habits (columns from left to right) globally throughout the week, on moderateintensity activity days, on high-intensity activity days and on veryhigh- intensity activity days.

Table 3: Results of daily caloric intake according to level of physical activity level.

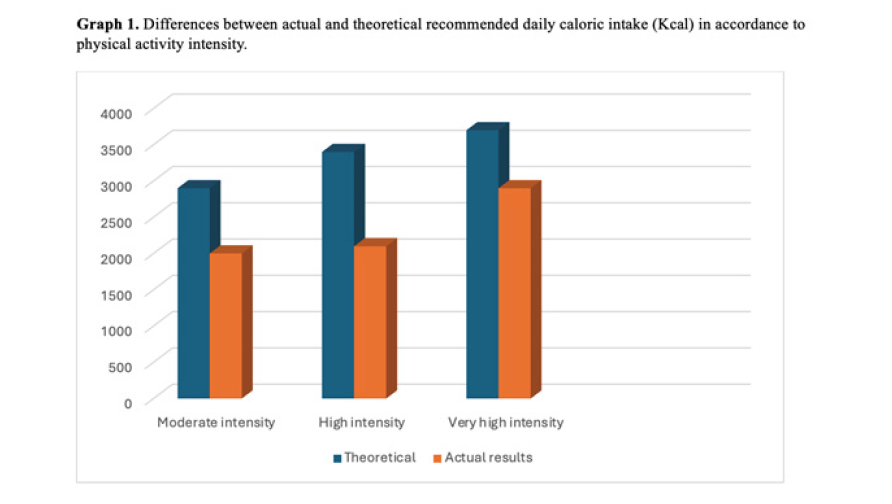

Figure 1:Differences between actual and theoretical recommended daily caloric intake (Kcal) in accordance to physical activity intensity.

Daily caloric intake varied significantly (p=0.000) according to physical demands on each given day (2940145Kcal on veryhigh- intensity days vs 2205223Kcal on high-intensity days vs 2139142Kcal on moderate-intensity activity days). The same trend can be found in CH consumption (36128gr/day vs 27630gr/day vs 21337gr/day). No significant differences were found in other macronutrient intake (PT or LP). However, as shown in Figure 1, real average caloric intake on moderate, high and very-high-intensity activity days still falls short of the theoretical energetic requirements recommended for professional soccer players.

Discussion

Athletic performance depends not only on ability, skill or time and quality of training, but on a balanced and sufficient diet engineered to adequately meet their physical needs. Optimal nutrition focuses on improved performance, faster recovery times, maintain player fitness and decreasing the risk or injury and disease [26]. It has been shown 25% of soccer-related injuries happen during the final quarter of the match, when players are physically and psychologically drained. There is no one food group that can fulfill players’ needs across the board; nutrition needs to be balanced and meals tailored to each day’s requirements. Soccer is a seasonal team sport, hence physical requirements are highly variable both in the long and short term. During training and match season there is an almost daily combination of moderate (jogging, pacing…) and high-intensity activity (sprinting, direction changes, jumping, charging…) [5]. Furthermore, not all players on the team have equal requirements. As our results show, there are significant physiological and anthropometric differences between the different player positions which translate into specific dietary requirements. For instance, we found goalkeepers are on average taller and have higher BMRs than other players (although this difference was only statistically significant between goalkeepers and wingers) and therefore globally have a higher energy expenditure rate.

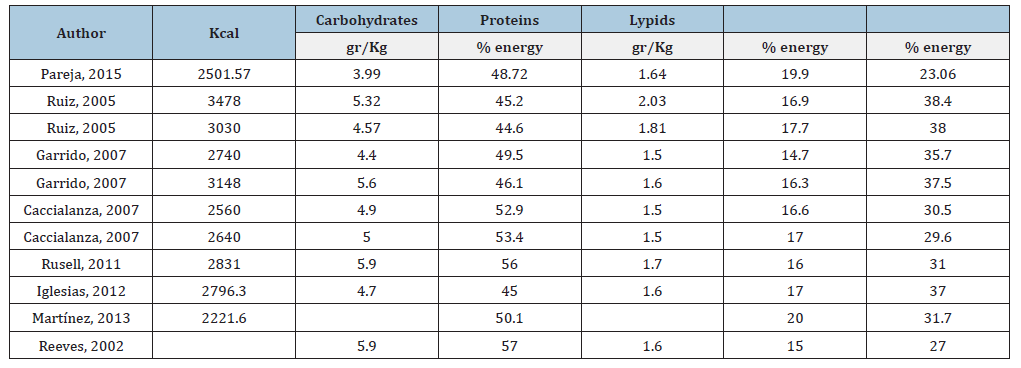

Our results are similar to others described in literature (Table 4) [5]. Although our average BMR and daily energy expenditure results are lower than those described by Martínez et al. [5] (1772.09 vs 1860.50 Kcal/ day), this can be explained by the anthropometric and age differences between their sample and ours. As previously mentioned, studies analysing energy expenditure in semi-professional athletes may introduce bias, as these players’ physical activity is not exclusively limited to training and playing with their team and is thus more difficult to accurately quantify. There is ample literature on the dietary requirements on soccer players [27,28]. This study focuses on the nutritional habits of one particular professional team with respect to macronutrient intake and its variation according to daily physical demand. Micronutrients were excluded from our analysis because there are no approved guidelines for micronutrient intake in athletes. General consensus amongst health experts in that an adequate supply of fruits, vegetables, nuts, blue fish, vegetable oils, etc., excludes the need for iron or vitamin supplementation, even amongst athletes with no known nutritional deficiencies [29]. According to the most recent guidelines, the recommended daily caloric consumption for young, highly-physically-active males in the Spanish population is 3600Kcal.

Table 4:Showing results obtained by different authors in similar studies as compared to our own.

Our findings fall short of this standard (2501328Kcal/day on average), as do other studies’, which have generally found soccer players to have a negative energetic balance [5]. This is true for both moderate and high-intensity activity days, yet we can see players tend to self-regulate and increase caloric and especially CH intake in accordance to projected physical demand of the day. We acknowledge our findings may be also be influenced by the aforementioned fact that all data was collected during a week where our players were part of the visiting team and therefore had to adapt to pre- and post-match meals being designed by the home team’s medical staff, which may or may not be a source of bias when interpreting results. Some studies recommend CH intake in athletes should be 500-600gr or 60-70% of total daily intake, as measured in gr/Kg. 5-7gr/Kg is the recommended CH intake on a moderateintensity activity day and 7-10gr/Kg on a very-high-intensity activity day [1,4,30]. Again, our findings fall short of this standard (2.741.2 and 4.640.9gr/Kg, respectively). This negative balance intake of CH amongst soccer players is supported the literature detailed in Table 4. On average, our findings pertaining to daily caloric and CH intake is lower than other studies’, but our population is on average older (all of them except Martínez et al. analyse data in juvenile teams) and only our study breaks down nutritional intake according to higher or lower physical demand. Other nutritional recommendations amongst the athletic population include a daily PT consumption of 98-119gr or 1.4-1.7gr/Kg and for LP be under 30% of daily calories. Most studies show players generally fall short of both standards, as do our own findings.

Conclusion

Athletic performance depends heavily on diet, which must be engineered to adequately meet players’ physical needs. Optimal nutrition focuses on improved performance, faster recovery times, mainting player fitness and decreasing the risk or injury and disease. There is no one food group that can fulfill players’ needs across the board; nutrition needs to be balanced and meals tailored to each day and player’s requirements. As predicted, our study found a deficient macronutrient intake in our sample as whole with respect to average energy expenditure and to the standards recommended in other studies and guidelines. However, care must be taken when interpreting these results due to a short follow-up time (one week) and small sample size of 22.

References

- García RM, García ZP, Patterson AM, Iglesias GE (2014) Nutrient intake and food habits of soccer players: Analyzing the correlates of eating practice. Nutrients 6(7): 2697-2717.

- Bangsbo J, Mohr M, Krustrup P (2006) Physical and metabolic demands of training and match-play in the elite football player. J Sports Sci 24(7): 665-674.

- Haugen TA, Tonnessen E, Seiler S (2013) Anaerobic performance testing of professional soccer players 1995-2010. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 8(2): 148-156.

- Burke LM, Loucks AB, Broad N (2006) Energy and carbohydrate for training and recovery. J Sports Sci 24(7): 675-685.

- Martínez RC, Sánchez CP (2013) Nutritional study of a third division football team. Hospital Nutrition 28(2): 319-324.

- Phillips SM, Van LJ (2011) Dietary protein for athletes: From requirements to optimum adaptation. J Sports Sci 29(Suppl 1): S29-S38.

- González J, Sánchez P, Mataix J (2006) Nutrition in sports. Ergogenic aids and doping. Díaz de Santos, Madrid, Spain.

- Chena M, Perez LA, Bores CA, Ramos CD (2014) Associations between body composition and neuromuscular performance in young soccer players. IV NSCA International Conference, Murcia, Spain, p. 128.

- Hawley JA, Tipton KD, Millard SL (2006) Promoting training adaptations through nutritional interventions. J Sports Sci 24(7): 709-721.

- Friedl KE, Moore RJ, Hoyt RW, Marchitelli LJ, Martínez LE, et al. (2000) Endocrine markers of semistarvation in healthy lean men in a multistressor environment. Journal of Applied Phisiology 88(5): 1820-1830.

- Loucks AB (2004) Energy balance and body composition in sports and exercise. J Sports Sci 22(1): 1-14.

- Anderson L, Orme P, Naughton RJ, Close GL, Milsom J, et al. (2017) Energy intake and expenditure of professional soccer players of the english premier league: Evidence of carbohydrate periodization. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 27(3): 228-238.

- Williams C, Serratosa L (2006) Nutrition on match day. J Sports Sci 24(7): 687-697.

- Burke LM, Hawley JA, Wong SH, Jeukendrup AE (2011) Carbohydrates for training and competition. J Sports Sci 29(Suppl 1): S17-S27.

- Kingsley M, Penas RC, Terry C, Russell M (2014) Effects of carbohydrate-hydration strategies on glucose metabolism, sprint performance and hydration during a soccer match simulation in recreational players. J Sci Med Sport 17(2): 239-243.

- Rusell M, Kingsley M (2014) The efficacy of acute nutritional interventions on soccer skill performance. Sports Medicine 44(7): 957-970.

- Roberts PA, Fox J, Peirce N, Jones SW, Casey A, et al. (2016) Creatine ingestion augments dietary carbohydrate mediated muscle glycogen supercompensation during the initial 24h of recovery following prolonged exhaustive exercise in humans. Amino Acids 48(8): 1831-1842.

- Jenjens R, Jeukendrup AE (2003) Determinants of post-exercise glycogen synthesis during short term recovery. Sports Medicine 33(2): 117-144.

- Lemond PR (1994) Protein requirements of soccer. J Sports Sci 12: S17-S22.

- Garrido G, Webster AL, Chamorro M (2007) Nutritional adequacy of different menu settings in elite Spanish adolescent soccer players. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 17(5): 421-432.

- Iglesias GE, García A, García ZP, Pérez LJ, Patterson AM, et al. (2012) Is there a relationship between the playing position of soccer players and their food and macronutrient intake? Appl Physiol Nutr Meta 37(2): 225-232.

- Russell M, Pennock A (2011) Dietary analysis of young professional soccer players for 1 week during the competitive season. J Strength Cond Res 25(7): 1816-1823.

- Durnin JV, Womersley J (1974) Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: Measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. British Journal of Nutrition 32(1): 77-97.

- Harris JA, Beendict FG (1918) A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 4(12):370-373.

- Mifflin MD, Jeor ST, Hill LA, Scott BJ, Daugherty SA, et al. (1990) A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am J Clin Nutr 51(2): 241-247.

- Iglesias E, García P, Patterson AM (2010) Assessment of the eating habits of elite athletes: The case of football. In: Varela G, Silvestre D (Eds.), Nutrition, active lifestyle and sport, España: IM &C, Madrid, Spain, pp. 161-183.

- Oliveira CC, Ferreira D, Caetano C, Granja D, Pinto R, et al. (2017) Nutrition and supplementation in soccer. Sports 5(2):28.

- Sousa M, Teixeira VH, Soares J (2014) Dietary strategies to recover from exercise-induced muscle damage. Int J Food Sci Nutr 65(2): 151-163.

- Bytomski JR (2018) Fueling for performance. Sports Health 10(1): 47-53.

- Hills S, Russell M (2017) Carbohydrates for soccer: A focus on skilled actions and half-time practices. Nutrients 10(1): 22.

© 2025 Mónica Sánchez Santiuste, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)