- Submissions

Full Text

Significances of Bioengineering & Biosciences

Biocatalysis in the Spotlight: Enzyme-Driven Asymmetric Synthesis for Precision Chemistry

Benson Ameh Agi1, Micheal Abimbola Oladosu2*, Moses Adondua Abah3, Dominic Agida Ochuele3, Abimbola Mary Oluwajembola2 and Olaide Ayokunmi Oladosu4

1Department of Chemistry, College of Science, University of Siegen, Germany

2Department of Chemical Sciences, Faculty of Science, Anchor University, Nigeria

3Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences, Federal University of Wukari, Nigeria

4Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Science and Technology, Babcock University, Nigeria

*Corresponding author:Micheal Abimbola Oladosu, Department of Chemical Sciences, Faculty of Science, Anchor University, Ayobo, Ipaja, Lagos, Nigeria

Submission: November 19, 2025; Published: December 15, 2025

ISSN 2637-8078Volume7 Issue 5

Abstract

With the increasing requirement for sustainable and accurate chemical synthesis, biocatalysis has become a prominent approach in contemporary organic synthesis. Enzymes provide unparalleled stereoselectivity in ecologically friendly circumstances, facilitating the efficient synthesis of chiral compounds. Biocatalysis presents numerous advantages: Initially, reactions are generally conducted within a moderate temperature range (4-60 °C), resulting in a reduced energy requirement for the reactions. Enzymes exhibit stability under industrial circumstances and can be utilised for extended periods without necessitating replacement or supplementation. These parameters are critically significant for bulk chemicals, as energy consumption and catalyst dependability substantially affect the final product pricing. Biocatalytic processes can be conducted in an aqueous environment, minimising solvent usage and the associated disposal or recycling expenses. Majority of enzymes frequently lack optimal suitability for industrial applications due to constraints related to temperature, pH, solvent stability, substrate specificity and activity restrictions. To address these restrictions, researchers have been devising strategies to emulate evolutionary processes to enhance the features of enzymes as needed. This review analyses the essential function of biocatalysis in asymmetric synthesis, investigating enzyme classifications, catalytic mechanisms, industrial applications and new advancements in enzyme engineering. It emphasises present obstacles and prospective potential, encompassing co-factor regeneration, enzyme immobilisation and AI-driven design. As industrial use increases, biocatalysis is transforming green chemistry and facilitating the scalable, environmentally sustainable manufacture of high-value compounds.

Keywords:Asymmetric synthesis; Enzymes; Biocatalysis; Industrial synthesis; Enzyme engineering

Introduction

The production of chiral molecules, crucial in medicines, agrochemicals and fine chemicals, requires meticulous precision. Conventional asymmetric synthesis techniques, although efficient, frequently encounter constraints like severe conditions, inadequate stereoselectivity and substantial waste production. Biocatalytic techniques generally produce fewer harmful by-products and trash compared to conventional chemical approaches [1]. Enzymatic applications in chemistry have a longstanding history, particularly in the food, textile and detergent sectors [2-4], however, biocatalysis began to significantly influence the fine chemical and pharmaceutical industries only in the early 21st century. In addition to the robust impetus for creating more ecologically sustainable chemical processes, the expedited access to proteins and the capacity to change them significantly influenced a paradigm shift in the industry [5,6]. Enzymes can rival conventional chemical (catalytic) processes for a wide array of chemical changes, including many previously deemed unnatural. The finding of the catalytic activity of aldoxime dehydratases in the Kemp elimination reaction is exemplary [2,7], as it involves the base-catalysed deprotonation of a benzisoxazole ring, for which only de novo designed proteins and chemical bases were previously recognised as active catalysts [2,8]. Enzymes are biodegradable, hence diminishing the environmental impact of the catalyst. Moreover, biocatalysis frequently transpires in aqueous environments, hence reducing the need on organic solvents [1]. Enzymes generally catalyse a singular type of chemical reaction, hence minimising the production of undesirable byproducts.

Enzymes can differentiate between several places within a molecule, catalysing processes at designated sites [1]. Enzymes can distinguish between various stereoisomers, yielding compounds with elevated enantiomeric or diastereomeric purity. This specificity originates from the exact three-dimensional configuration of the enzyme’s active site, where substrate binding and catalysis take place. The active site is designed to engage with certain substrates via a variety of noncovalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces and hydrophobic interactions [1,9,10]. Enzymes have been utilised in several chemical processes for numerous years [11,12]. Currently, thousands of tonnes of acrylamide are generated utilizing nitrile hydratases and enzymes have been incorporated into detergents for more than thirty years [11,13]. Recently, there has been an increasing trend in utilising proteins as catalysts in the chemical synthesis of more complex molecules, including pharmaceuticals. Enzymes are particularly effective as they integrate the advantages of a catalyst and a directing group to regulate the selectivity of a single reagent, which may also be employed alongside other enzymes in a one-pot reaction [13]. Once restricted to laboratory settings, biocatalysis is now used on an industrial scale, enabling the efficient synthesis of complex compounds. The enzymatic synthesis of esters utilising lipases was established in 1916 [11,14]. Biocatalysis offers insights for research and addresses chemo-selectivity and efficiency challenges that conventional chemistry cannot resolve [11,15].

Biocatalysis is presently acknowledged as a developed technology for asymmetric synthesis, attributed to the remarkable selectivity (enantio-, chemo- and regio-) that enzymes frequently exhibit in numerous chemical processes [16]. The discipline has undergone significant advancement as emerging molecular biology approaches for enzyme production and design have been integrated with process development concepts (from batch to continuous reactors) and medium engineering strategies (such as non-aqueous media and immobilisation). Consequently, biocatalysis may often meet the requirements of contemporary organic synthesis, which necessitates a balance of high selectivity and efficiency with sustainability and stringent economic considerations. Consequently, a growing array of industrial processes has been effectively implemented, including many examples that utilise free enzymes, entire cells, biocatalytic systems and multi-step processes, among others [16-19]. Biocatalysis guarantees uniformity, safety and quality in food production [1]. The fine chemicals and flavour sectors derive advantages from biocatalysis by producing high-value molecules, including vitamins, amino acids and flavour enhancers. Enzymes provide a sustainable and economical pathway to these molecules [1]. Notwithstanding the myriad advantages, biocatalysis encounters problems that must be resolved to completely actualise its potential.

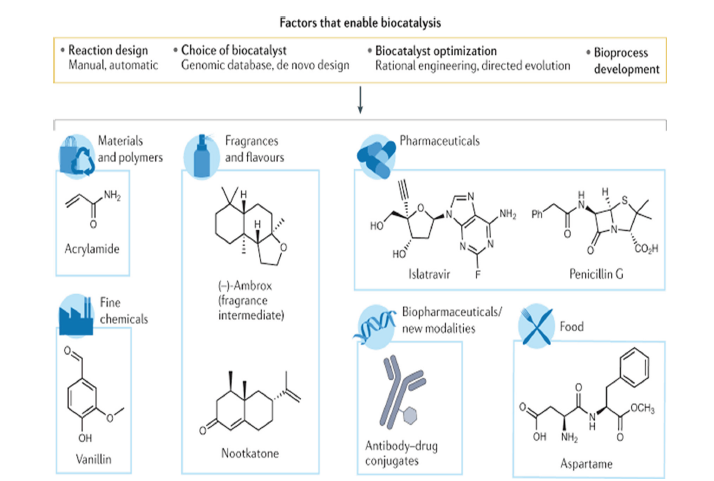

Figure 1:Examples of different products synthesized using biocatalysis [22].

The stability of enzymes under industrial circumstances, the requirement for co-factors and the restricted availability of appropriate enzymes for specific reactions pose considerable challenges [1]. Progress in protein engineering, guided evolution and synthetic biology is essential for addressing these difficulties. These approaches facilitate the alteration of enzymes to improve their stability, activity and selectivity [20,21]. This paper examines the disparity between enzyme discovery and industrial application, with an emphasis on asymmetric conversions. This review seeks to assess principal enzyme classes utilised in enantioselective synthesis, processes facilitating stereocontrol, successful industrial applications, strategies for enzyme enhancement and prospective approaches [12] (Figure 1).

Enzyme Classes and Catalytic Mechanisms

Different kinds of enzymes, each with distinct catalytic characteristics, are used in biocatalytic asymmetric synthesis. Oxidoreductases (EC 1), Transferases (EC 2), Hydrolases (EC 3), Lyases (EC 4), Isomerases (EC 5) and Ligases (EC 6) are important classes of enzymes.

Oxidoreductases (EC 1)

One-third of the enzymatic activities reported in BRENDA are catalysed by oxidoreductases, also known as oxireductases, which catalyse the oxidation-reduction reaction in the form of A*+B=A+B* [22]. The presence of cofactors like flavin, heme and other metal ions is another essential feature of oxidoreductases. Fungal oxidoreductases are made up of heme-containing peroxidases, which are a subset of the classical Lignin-Modifying Peroxidases (LMPs), Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenases (LPMOs), flavincontaining oxidases and dehydrogenases, heme-containing peroxygenases and Dye-Decolorizing Peroxidases (DyPs). Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) is broken down by peroxidases (EC 1.11.1.x), which also oxidise phenolic and nonphenolic substrates. They can be found in bacteria, fungus, algae, plants and animals, making them ubiquitous throughout nature. They are linked to a number of plant growth processes, such as the metabolism of cell walls, lignification, suberization, reactive oxygen species, auxins, fruit ripening and growth and pathogen defence. They can be effectively used in immunological and biotechnological applications in medicine as well as a variety of industrial industries [23]. Aryl-alcohol oxidase (EC 1.1.3.7), methanol oxidase (EC 1.1.3.13), pyranose 2-oxidase (EC 1.1.3.10), glucose oxidase (EC 1.1.3.7), vanillyl-alcohol oxidase (EC 1.1.3.38), eugenol oxidase (EC, 1.17.99.1), cellobiose dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.99.18) and glucose dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.99.35) are just a few examples of flavin-containing oxidases and dehydrogenases.

Flavin oxidases and dehydrogenases are peroxidases that produce H2O2 by removing two electrons from alcohol substrates. O2 then reoxidises the reduced flavin to produce H2O2 [24]. Applications for this class of enzymes in biorefineries, including flavour synthesis, furfural oxidation, biobleaching and chiral alcohol deracemization, have been investigated. The Copper (Cu)-containing enzymes known as Polyphenol Oxidases (PPOs) oxidise phenolic substances to o-quinones, which in turn trigger subsequent processes that result in the formation of melanins and cross-linked polymers. Tyrosinases, catechol oxidases and laccases are the three categories into which PPOs fall. Their method of action and substrate specificity serve as the foundation for these classifications. Catechol oxidases catalyse the conversion of o-diphenols to o-quinones, whereas tyrosinases exhibit both cresolase and catecholase activities [25]

Transferases (EC 2)

The movement of a certain group from one substance to another is catalysed by transferases. Methyl, acyl, amino, glycosyl or phosphate are examples of related groups. Enzymes known as Glutathione Transferases (GSTs, EC 2.5.1.18) aid in the detoxification of both endogenous and exogenous electrophile substances [26]. The Enzyme Cis-Prenyltransferase (EC 2.5.1.20), often known as rubber transferase, catalyses the elongation of rubber molecules [27] by sequentially condensing isopentenyl pyrophosphate with prenyl groups [28]. Because GSTs can catalyse conjugation events, they have been investigated in the biosensors technology for herbicide detection. For instance, atrazine was previously identified utilising the immobilised maize GST I isoenzyme. Since GSTs are involved in the detoxification of several chemotherapeutics and are therefore thought to be potentially essential in controlling the susceptibility to cancer, cytosolic GSTs may be helpful in the diagnosis and monitoring of cancer [26].

Hydrolases (EC 3)

The EC number three designates hydrolases, which are enzymes with the capacity to hydrolyse a variety of bonds. A variety of designations are used based on their substrate specificity: Ester bond hydrolases (EC 3.1), including thioester hydrolases (EC 3.1), glycosylases (EC 3.2), ether bond hydrolases (EC 3.3), peptide bond hydrolases (EC 3.4) and other hydrolases. Glycoside hydrolases (GHs), a highly significant subgroup, work on the glycosidic bonds that bind two or more carbs together [29]. The Carbohydrate- Active Enzymes (CAZy) database describes this group, which is also known as glycosidases [30]. Amylases, xylanases, cellulases, lipases and proteases are a few types of significant hydrolases.

Lyases (EC 4)

By breaking nonhydrolytic bonds, lyases catalyse the addition or removal of chemical groups. By cleaving C_C, C_O, C_N, C_S and other bonds, these enzymes can create new rings, double bonds or add groups to existing ones [31,32]. The lyases in class 4 (EC 4) are assigned an EC number. The second number, which represents the eight subclasses of lyases, illustrates the sort of bond that is involved in the reactions: Lyases with the following EC numbers: EC 4.1 carbon carbon, EC 4.2 carbon oxygen, EC 4.3 carbon nitrogen, EC 4.4 carbon sulphur, EC 4.5 carbonhalide, EC 4.6 phosphorus oxygen, EC 4.7 carbonphosphorus and EC 4.99 other lyases. Based on the chemical group removed, these subclasses have subcategories that correspond to the third number [33,34]. Aldolases, decarboxylases, hydratases and some pectinases are members of this category of enzymes that catalyse the removal of aldehyde, carbon dioxide, water and pectin molecules, respectively [31,35]. They are involved in signal transduction, the mechanism of DNA repair and metabolic and anabolic pathways [36]. Lyases, which feature structures called tunnels and gates that control the movement of substances, are catalysed by the keyhole-lock-key model [37].

Isomerases (EC 5)

The fifth group of the EC Classification (EC 5) is made up of the enzyme class known as isomerases. Depending on the kind of reaction they catalyse, they are classified into seven subclasses and can catalyse intramolecular rearrangements or isomerisation reactions: Racemases and epimerases (EC 5.1) that catalyse the racemization or epimerization of a centre of chirality; cistrans isomerases (EC 5.2) that catalyse the rearrangement of geometry at double bonds; intramolecular oxidoreductases (EC 5.3) that catalyse the oxidation of a portion of a molecule with the simultaneous reduction of another portion; intramolecular transferases (EC 5.4) that move a group from one location within a molecule; intramolecular lyases (EC 5.5) that catalyse reactions where a group is removed from one part of a molecule, leaving a double bond but remaining covalently attached to the molecule (e.g., the breaking of a ring structure); isomerases that change the conformation of macromolecules; and other isomerases (EC 5.99) [38].

Ligases (EC 6)

Ligases (EC 6) represent the sixth class of enzymes. At the cellular level, the majority of them participate in biologically necessary activities in the central metabolism. The attachment of two molecules or portions of them is catalysed by them. NAD 1 synthase (EC 6.3.1.5) and pyruvate carboxylase (EC 6.4.1.1) are two examples of ligases that can occasionally be referred to by the label’s synthase or carboxylase [39]. Condensation reactions, or the creation of phosphoricester and nitrogen metal linkages, carbon carbon, carbon sulphide, carbon nitrogen and carbon oxygen, are catalysed by ligases [40,41] (Table 1 & Figure 2).

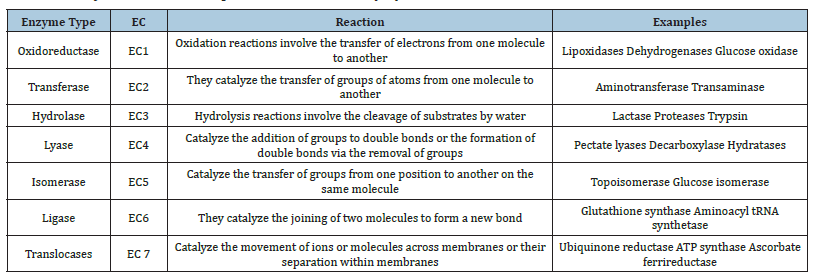

Table 1: Enzyme classes and representative reactions [41].

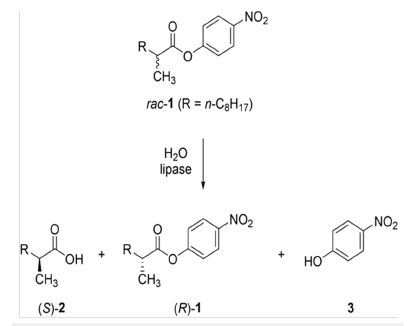

Figure 2:Mechanism of lipase-catalyzed kinetic resolution [42].

Industrial Applications

Industrial asymmetric synthesis can now be solved practically with biocatalysis. It is used in fine chemicals, agrochemicals, flavour and fragrance, medicines and cosmetics. In many fine chemicals, agrochemicals and medicines, chiral alcohols are significant structural and functional motifs [42]. Chiral hydroxylcontaining building blocks are essential intermediates of several APIs of potential drugs in the pharmaceutical industry [43]. The lack of metal-based catalysts, mild conditions, stereocontrol in the synthesis and a smaller environmental impact are the clear reasons why biocatalysis is so popular for obtaining chiral alcohols. In the agricultural and pharmaceutical industries, chiral amines are crucial. Over 90% of the most popular small molecule medications on the market now or those that have just received approval are either amines or derivatives of amines. The majority of them are chiral and chiral amine compounds make up around 30% of crop protection actives. Thus, there is a particular emphasis on optically pure amines in biocatalysis [44]. The chemical, food, material and pharmaceutical industries all make extensive use of carboxylic acids. The industrial synthesis of high-value (chiral) carboxylic acids is the best application for biocatalysis. Biocatalysis has demonstrated promise for the generation of bulk carboxylic acids at the laboratory scale, thanks to recent developments in directed evolution and enzyme cascades [45].

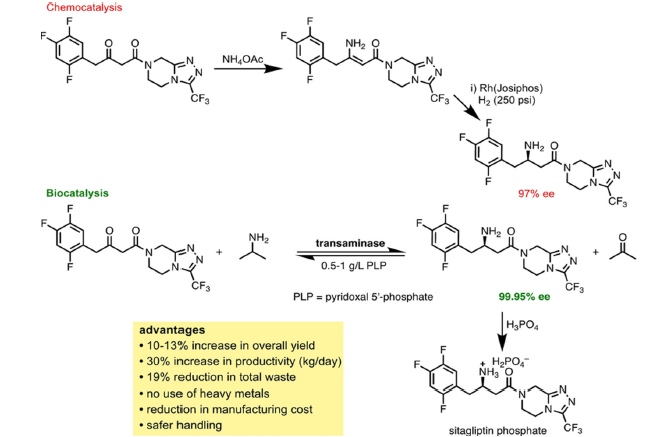

Common organic compounds that are typically created by chemical reactions are aldehydes and ketones. The customer’s demand for “all-natural production” in terms of flavours and perfumes, as well as the high regioselectivity to create ketoses, are some benefits that biocatalytic processes may offer. Generally speaking, the two primary methods for producing aldehydes and ketones efficiently are alcohol oxidation by dehydrogenases or oxidases [46] and C-C bond formation by aldolases or lyases [47]. Due to their greater yields, improved crystallisation, salt breaking and ease of reusing the chiral auxiliary, enzymes are already used in the manufacture of around two thirds of chiral compounds on an industrial scale [48,49]. A variety of chiral medications, such as atorvastatin (Lipitor), rosuvastatin (Crestor), sitagliptin (Januvia) and montelukast (Singulair) are made by biocatalyzed processes. Although the use of enzymes has been receiving more attention for the organic synthesis of high-value products, including pharmaceuticals, flavours and fragrances, vitamins, fine chemicals and some commodities, industrial biocatalysis is still an exception rather than the rule [48,50]. Enzymes or cells are used by companies like Avecia, Basf, Evonik, DSM, Dow Pharma and Lonza to chirally synthesise their compounds [48,51]. Additionally, Evonik uses immobilised lipases to produce cosmetic agents, speciality esters and fragrance compounds [48,52-54] (Table 2 & Figure 3).

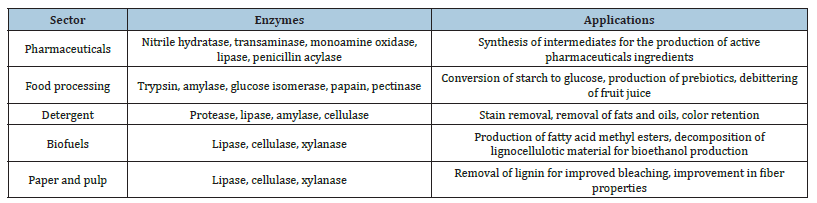

Table 2:Industrial applications of enzyme catalysis [54].

Figure 3:Enzymatic (biocatalytic) synthesis of sitagliptin [55].

Enzyme Engineering and Directed Evolution

Directed evolution and protein engineering are becoming crucial tools for overcoming the limits of natural enzymes. If used as therapeutic agents, enzymes must be both safe and effective in order to produce the anticipated clinical benefit [55]. Making a library of target enzyme mutants is the first stage in any enzyme evolution campaign [56]. It is hoped that a good solution will be found in the sequence space sampled by these mutants, which will be revealed by the screening procedure [56]. A new age in the therapeutic sector began with the development of protein engineering and recombinant technology, which can address all of these issues to some degree [55]. For maximum efficacy, protein therapy enzymes with high specificity and potency need to be delivered precisely at the nanoscale. As a result, the drug delivery medium, including drug carriers and moieties for targeted distribution, rapidly changed in less than ten years [55,57]. Through amino acid sequence modifications, Sudhir et al. [58] produced glutaminase free L-asparaginase from Bacillus licheniformis to enhance its half-life and thermal characteristics. Based on hydrophobicity, electrostatic potential and sequence matching with previously modified asparaginases, four amino acid residues were chosen for mutagenesis [55,58]. In comparison to the natural type protein, the mutant D103V exhibited a three-fold longer half-life and greater resistance to heat. With a Vmax of 2778.9mol min-1 and a Km value of 0.42mM, the mutant also demonstrated enhanced substrate affinity. Patel et al. [59] used molecular dynamics and genetic algorithms to create an E. coli enzyme that is resistant to lysosomal proteases.

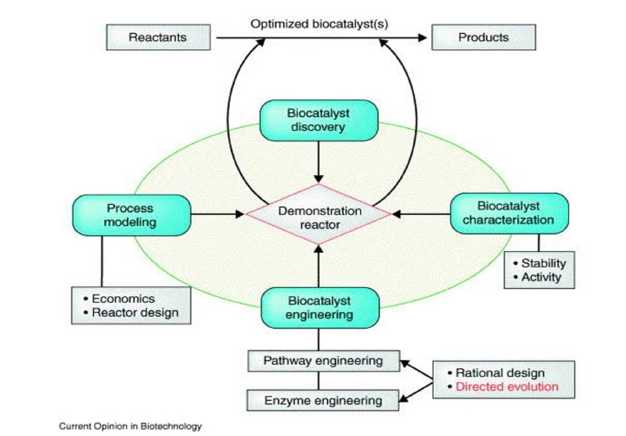

A protein engineering technique called “directed evolution” imitates the course of natural evolution to modify proteins in ways that the user specifies [55]. This lab procedure focusses on particular molecular characteristics and operates at the molecular level [55]. Kotzia and Labrou developed a library of variations by applying a staggered extension technique to the L-asparaginase genes from E. carotovora and E. chrysanthemi [60]. A thermostable variant with a single point mutation at position 133, where the negatively charged amino acid aspartate was swapped out for alanine, was chosen and discovered from the screened members. The mutant exhibited superior thermal characteristics, such as Tm and half-life, in comparison to the wild enzyme [55]. A cluster of variations for screening can be created by randomly introducing mutations in a gene sequence, taking advantage of the limitations of DNA repair systems and polymerases [55]. A variety of techniques were used to generate random mutant libraries, such as chemical mutagens, utilising the altered strains (E. coli XL1red) and errorprone PCR. The random mutation of B. subtilis’s L-asparaginase II resulted in variants with better characteristics, according to Feng et al. [61]. Enhancing substrate scope, thermostability, tolerance to organic solvents and enantioselectivity are the objectives of all of these [62] (Figure 4).

Figure 4:Flowchart illustrating the development of industrial biocatalytic processes [63].

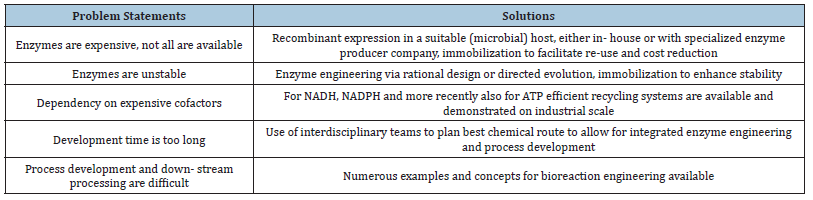

Challenges and Future Directions

The adaptation of pre-existing enzymes for industrial, research and medical applications has greatly benefited society [63,64]. Even though biocatalysis is already relevant in industry, there are still issues. Due to restrictions on substrate specificity, activity, pH, temperature and solvent stability, pre-existing enzymes are frequently not the best for industrial applications [65,66]. Since enzymes may function at low pressures and temperatures, they are frequently denatured when exposed to environments that are outside of their typical range [67]. Even tiny concentrations of organic solvents can denature a variety of enzymes [67]. One of the difficulties is predicting how the scale-up from laboratory-scale fermentations to industrial-scale ones would affect the production of recombinant proteins and another is the inability to cultivate a large number of microorganisms in the lab [68]. Although examples of biocatalysis-based bulk chemical and polymer manufacturing are relatively uncommon, they present a wealth of opportunities for green chemistry [12]. The production of biomacromolecules and antibody-drug conjugates are two examples of the new modalities that biocatalysis can help the biopharmaceutical industries create more effectively and selectively [12]. Looking ahead, a number of important developments and scientific trends are expected to significantly accelerate the discovery, development and use of biocatalysts [12]. First, de novo design [68,69] and/or directed evolution [70] are being used to rapidly increase the range of chemical, novel biocatalytic reactions.

Better selection techniques for finding appropriate biocatalysts from the wealth of protein primary sequence information presently available in databanks will be made possible by increasingly potent computational tools, which will also enable better de novo design. Advances in computational methods to predict the protein structure from sequences through artificial intelligence [71] and subsequent prediction of function and physicochemical properties will provide access to biocatalysts that are finely tuned to the requirements of a desired target reaction and/or product [72]. These tools must be combined with the development of novel biocatalytic cascade processes in order to optimise synthetic utility. Desktop DNA printing, cell-free protein expression, enzyme immobilisation and analysis are just a few of the individual steps in the development of biocatalysts that can already be automated at the implementation stage. This suggests that within the next ten years, individual laboratories may be able to purchase “fully automated biocatalytic synthesisers” [12,73] (Table 3).

Table 3:Challenges in biocatalysis and solutions [73].

Conclusion

Asymmetric synthesis is being revolutionised by biocatalysis, which makes precise, environmentally benign and scalable reactions possible. The sector is quickly overcoming past constraints thanks to advancements in enzyme discovery, engineering and process integration. Biocatalysis will be essential to the next generation of environmentally friendly chemical production as the nexus of biotechnology, automation and artificial intelligence continues to develop.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledged all the authors of this work for their valuable contribution..

Conflict of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest, according to the authors.

References

- Marie A (2024) Biocatalysis in organic synthesis: Enzymatic pathways to green chemistry. Chemical Sciences Journal 15: 02.

- Hall M (2021) Enzymatic strategies for asymmetric synthesis. RSC Chem Biol 2(4): 958-989.

- Bornscheuer UT, Buchholz K (2005) Highlights in biocatalysis-historical landmarks and current trends. Eng Life Sci 5(4): 309-323.

- Heckmann CM, Paradisi F (2020) Looking back: A short history of the discovery of enzymes and how they became powerful chemical tools. ChemCatChem 12(24): 6082-6102.

- Truppo MD (2017) Biocatalysis in the pharmaceutical industry: The need for speed. ACS Med Chem Lett 8(5): 476-480.

- Adams JP, Brown MB, Diaz RA, Lloyd RC, Roiban GD (2019) Biocatalysis: A pharma perspective. Adv Synth Catal 361(11): 2421-2432.

- Miao YF, Metzner R, Asano Y (2017) Kemp elimination catalyzed by naturally occurring aldoxime dehydratases. ChemBioChem 18(5): 451-454.

- Röthlisberger D, Khersonsky O, Wollacott AM, Jiang L, Chancie DJ, et al. (2008) Kemp elimination catalysts by computational enzyme design. Nature 453(7192): 190-195.

- Anastas P, Nicolas E (2010) Green chemistry: Principles and practice. Chem Soc Rev 39: 301-312.

- Trost BM (1991) The atom economy-a search for synthetic efficiency. Sci 254(5037): 1471-1477.

- Jagtap NP, Somwanshi PP, Nalegaonkar SS, Palkar HN, Mungale SD, et al. (2024) Biocatalysis for green synthesis: Exploring the use of enzymes and micro-organisms as catalysts for organic synthesis, highlighting their advantages over traditional chemical catalysts in terms of selectivity, efficiency and environmental impact. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research (IJFMR) 6(2): 2582-2160.

- Bell EL, Finnigan W, France SP, Green AP, Hayes MA, et al. (2021) Biocatalysis. Nat Rev Methods Primers 1: 46.

- Yamada H, Kobayashi M (1996) Nitrile hydratase and its application to industrial production of acrylamide. Biosci Biotechnology Biochem 60(9): 1391-1400.

- Koivisto AJ, Aromaa M, Mäkelä JM, Pasanen P, Hussein T, et al. (2012) Concept to estimate regional inhalation dose of industrially synthesized nanoparticles. ACS Nano 6(2): 1195-1203.

- Varma SR (2016) Greener and sustainable trends in synthesis of organics and nanomaterials. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 4(11): 5866-5878.

- Dominguez PD, Gonzalo DG, Alcántara RA (2019) Biocatalysis as useful tool in asymmetric synthesis: An assessment of recently granted patents. Catalysts 9(10): 802.

- Turner NJ, Kumar R (2018) Editorial overview: Biocatalysis and biotransformation: The golden age of biocatalysis. Curr Opin Chem Biol 43: A1-A3.

- Sheldon RA, Brady D (2018) The limits to biocatalysis: Pushing the envelope. Chem Commun 54(48): 6088-6104.

- Rosenthal K, Lutz S (2018) Recent developments and challenges of biocatalytic processes in the pharmaceutical industry. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem 11: 58-64.

- Tulus V, Javier PR, Gonzalo GG (2021) Planetary metrics for the absolute environmental sustainability assessment of chemicals. Green Chem 23(24): 9881-9893.

- Galán MÁ, Tulus V, Ismael D, Carlos P, Javier PR, et al. (2021) Sustainability footprints of a renewable carbon transition for the petrochemical sector within planetary boundaries. One Earth 4(4): 565-583.

- Vidal LS, Kelly CL, Mordaka PM, Heap JT (2018) Review of NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases: Properties, engineering and application. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom 1866(2): 327-347.

- Lundell TK, Makela MR, Hilden K (2010) Lignin-modifying enzymes in filamentous basidiomycetes ecological, functional and phylogenetic review. J Basic Microbiol 50(1): 5-20.

- Martínez AT, Francisco JD, Camarero S, Serrano A, Linde D, et al. (2017) Oxidoreductases on their way to industrial biotransformations. Biotechnol Adv 35(6): 815-831.

- Taranto F, Pasqualone A, Mangini G, Tripodi P, Miazzi MM, et al. (2017) Polyphenol oxidases in crops: Biochemical, physiological and genetic aspects. Int J Mol Sci 18(2): 377.

- Chronopoulou EG, Labrou NE (2009) Glutathione transferases: Emerging multidisciplinary tools in red and green biotechnology. Recent Pat Biotechnol 3(3): 211-223.

- Cornish K, Xie W (2012) Natural rubber biosynthesis in plants: Rubber transferase. Methods Enzymiol 515: 63-82.

- Spanò D, Pintus F, Esposito F, Loche D, Floris G, et al. (2015) Euphorbia characias latex: Micromorphology of rubber particles and rubber transferase activity. Plant Physiol Biochem 87: 26-34.

- IUBMB-International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of London.

- Glycoside hydrolase family classification. CAZy-Carbohydrate-Active Enzymes.

- Pandey A, Ramachandran S (2010) Enzyme technology. In: Pandey A, Webb C, Soccol CR, Larroche C (Eds.), Asiatech Publishers INC, New Delhi, India, pp. 1-10.

- Palmer T, Bonner PL (2011) Enzymes: Biochemistry, biotechnology, clinical chemistry, Woodhead Publishing, Sawston, UK.

- Brovetto M, Gamenara D, Mendez PS, Seoane GA (2011) C-C bond-forming lyases in organic synthesis. Chem Rev 111(7): 4346-4403.

- Donald AG, Boyce S, Tipton KF (2015) Enzyme classification and nomenclature. ELS, John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, UK, p. 111.

- Singh RS, Singh T, Pandey A (2019) Microbial enzymes-an overview. In: Singh RS, Singhania RR, Pandey A, Larroche C (Eds.), Biomass, Biofuels, Biochemicals: Advances in Enzyme Technology, Elsevier, Netherlands, p. 140.

- Buchholz K, Kasche V, Bornscheuer UT (2012) Biocatalysts and enzyme technology. Wiley-Blackwell, Weinheim, Germany.

- Li Q, Mavrodi DV, Thomashow LS, Roessle M, Blankenfeldt W (2011) Ligand binding induces an ammonia channel in 2-Amino-2-Desoxyisochorismate (ADIC) synthase PhzE. J Biol Chem 286(20): 18213-18221.

- (2019) Brenda. The Comprehensive Enzyme Information System 5: 265.

- Kashyap DR, Vohra PK, Chopra S, Tewari R (2001) Applications of pectinases in the commercial sector: A review. Bioresour Technol 77(3): 215-227.

- Barrett AJ (1994) Enzyme nomenclature. Recommendations 1992. Supplement: Corrections and additions Eur J Biochem 223: 1-5.

- Reetz MT, Zonta A, Schimossek K, Liebeton K, Jaeger KE (1997) Creation of enantioselective biocatalysts for organic chemistry by in vitro Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 36(24): 2830-2832.

- Chen BS, Souza FR (2019) Enzymatic synthesis of enantiopure alcohols: Current state and perspectives. RSC Adv 9(4): 2102-2115.

- Hollmann F, Arends IE, Holtmann D (2011) Enzymatic reductions for the chemist. Green Chem 13(9): 2285-2314.

- Ferrandi EE, Monti D (2017) Amine transaminases in chiral amines synthesis: Recent advances and challenges. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 34(1): 13.

- France SP, Hepworth LJ, Turner NJ, Flitsch SL (2017) Constructing biocatalytic cascades: In vitro and in vivo approaches to de novo multi-enzyme pathways. ACS Catal 7(1): 710-724.

- Kroutil W, Mang H, Edegger K, Faber K (2004) Biocatalytic oxidation of primary and secondary alcohols. Adv Synth Catal 346(2): 125-142.

- Clapes P, Fessner WD, Sprenger GA, Samland AK (2010) Recent progress in stereoselective synthesis with aldolases. Curr Opin Chem Biol 14(2): 154-167.

- Leitão VS, Cammarota MC, Aguieiras EG, Vasconcelos LR, Lafuente RF, et al. (2017) The protagonism of biocatalysis in green chemistry and its environmental benefits. Catalysts 7(1): 9.

- Downey W (2013) Trends in biopharmaceutical contract manufacturing. Chim Oggi-Chem 31: 19-24.

- Ciriminna R, Pagliaro M (2013) Green chemistry in the fine chemicals and pharmaceutical industries. Org Process Res Dev 17(12): 1479-1484.

- Wenda S, Illner S, Mell A, Kragl U (2011) Industrial biotechnology-the future of green chemistry? Green Chem 13(11): 3007-3047.

- Ansorge SB, Thum O (2013) Immobilised lipases in the cosmetics industry. Chem Soc Rev 42(5): 6475-6490.

- Dwevedi A, Yogesh KS (20121) Modulation of polymer-based immobilized enzymes for industrial scale applications. In: Alka D (Eds.), Polymeric Supports for Enzyme Immobilization, Academic Press, USA, pp. 69-103.

- Sharma S, Das J, Braje W, Dash AK, Handa S (2020) A glimpse into green chemistry practices in the pharmaceutical industry. ChemSusChem 13(11): 2859-2875.

- Vidya J, Sajitha S, Ushasree MV, Sindhu R, Binod P, et al. (2017) Genetic and metabolic engineering approaches for the production and delivery of L-asparaginases: An overview. Bioresource Technology 245(B): 1775-1781.

- Nirantar SR (2021) Directed evolution methods for enzyme engineering. Molecules 26(18): 5599.

- Muzykantov VR (2011) Targeted therapeutics and nanodevices for vascular drug delivery: Quo vadis? IUBMB Life 63(8): 583-585.

- Sudhir AP, Agarwaal VV, Dave BR, Patel DH, Subramanian RB (2016) Enhanced catalysis of l-asparaginase from Bacillus licheniformis by a rational redesign. Enzyme Microb Technol 86: 1-6.

- Patel N, Krishnan S, Offman MN, Krol M, Moss CX, et al. (2009) A dyad of lymphoblastic lysosomal cysteine proteases degrades the antileukemic drug L-asparaginase. The J Clini Investig 119(7): 1964-1973.

- Kotzia GA, Labrou NE (2009) Engineering thermal stability of L-asparaginase by in vitro directed evolution. The FEBS J 276(6): 1750-1761.

- Feng Y, Liu S, Jiao Y, Gao H, Wang M, et al. (2017) Enhanced extracellular production of L-asparaginase from Bacillus subtilis 168 by B. subtilis WB600 through a combined strategy. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101(4): 1509-1520.

- Zhao H, Chockalingam K, Chen Z (2002) Directed evolution of enzymes and pathways for industrial biocatalysis. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 13(2): 104-110.

- Chen CY (2014) DNA polymerases drive DNA sequencing-by-synthesis technologies: Both past and present. Front Microbiol 5: 305.

- Zhu H, Zhang H, Xu Y, Laššáková S, Korabečná M, et al. (2020) PCR past, present and future. Biotechniques 69(4): 317-325.

- Minteer SD (2017) Micellar enzymology for thermal, pH and solvent stability. Methods Mol Biol 1504: 19-23.

- Alfaro CL, Liu JW, Porter JL, Goldman A, Ollis DL (2019) Improving on nature’s shortcomings: Evolving a lipase for increased lipolytic activity, expression and thermostability. Protein Eng Des Sel 32(1): 13-24.

- Timson JD (2019) Four challenges for better biocatalysts. Fermentation 5(2): 39.

- Schmidt FR (2005) Optimization and scale up of industrial fermentation processes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 68(4): 425-435.

- Basler S, Sabine S, Yike Z, Takahiro M, Yusuke O, et al. (2021) Efficient lewis acid catalysis of an abiological reaction in a de novo protein scaffold. Nat Chem 13(3): 231-235.

- Liu Z, Arnold FH (2021) New-to-nature chemistry from old protein machinery: Carbene and nitrene transferases. Curr Opin Biotechnol 69: 43-51.

- Callaway E (2020) ‘It will change everything’: DeepMind’s AI makes gigantic leap in solving protein structures. Nature 588(7837): 203-204.

- Dou J, Anastassia AV, William S, Lindsey AD, Hahnbeom P, et al. (2018) De novo design of a fluorescnce activating β-barrel. Nature 561(7724): 485-491.

- Wu S, Snajdrova R, Moore JC, Baldenius K, Bornscheuer UT (2021) Biocatalysis: Enzymatic synthesis for industrial applications. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 60(1): 88-119.

© 2025 Micheal Abimbola Oladosu, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)