- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Development in Material Science

Acoustic Waves in Crystals and Discontinuity of Time

Kirk C Valanis*

Fellow ASME, USA

*Corresponding author:Kirk C Valanis, Fellow ASME, Endochronics Co, 839 Carriage Hill Rd, Melbourne FL 32940, USA

Submission: December 05, 2025;Published: January 19, 2026

ISSN: 2576-8840 Volume 22 Issue 4

Abstract

The problem of propagation of acoustic waves in a linear infinite crystal is solved. When time is continuous, the solution of the equation of motion leads to strange results, in regard to the wave speed and the capacity of waveforms to propagate. The conundrum needs resolution. Discontinuous time is posited and Newton’s Law of Motion becomes inoperable. A nanomechanical equation of motion, based on temporal discontinuity, is proposed and solved with the following natural physical outcomes. The wave speed depends only on the bond strength, atomic mass and interatomic distance. All initial atomic configurations propagate, at the same speed.

Keywords:Crystal acoustic waves; Acoustic wave speed; Newton’s law challenge; Discontinuous time

HighlightsThe problem of propagation of acoustic waves in a linear infinite crystal is solved. When time is continuous, the solution of the equation of motion leads to strange results, in regard to the wave speed and the capacity of wave forms to propagate. Discontinuous time is posited and Newton’s Law of Motion becomes inoperable. A nanomechanical equation of motion, based on temporal discontinuity, is proposed and solved with the following natural physical outcomes. The wave speed depends only on bond strength, atomic mass and interatomic distance. All initial atomic configurations propagate, at the same speed.

Introduction

Wave propagation in crystals is a complex problem that needs to be addressed in its full extent. X-ray diffraction experiments show that a crystal is an ordered assemblage of atoms, known as a lattice. The Bragg angle of diffraction, relating to the lattice spacing, is a case in point. We shall refer to the lattice spacing, i.e., the distance between atoms, by the letter ‘a’. In numerous articles on this subject, a crystal is idealized into a continuum with a corresponding anisotropy [1-9]. Following this idealization, linear elasticity in conjunction with Newton’s 2nd Law of motion, leads to the outcome that all acoustic waves, irrespective of their shape, propagate in a ‘continuum crystal’ at a fixed speed, that depends on the crystal’s continuum elastic constants and its mass density. This idealization has been used extensively in the past in the study of acoustic waves in crystals [1-9] which are invariably anisotropic. It is evident that it was important to the authors to concentrate on the effects of anisotropy on the nature of acoustic waves, their form, velocity and motion, in the course of their propagation in a crystal. The total problem, however, i.e., the anisotropy and the discrete atomic structure combined, presents a difficult challenge and it was reasonable to assume [1-9], that the atomic structure could be homogenized as is usually done in continuum mechanics, thus reducing the study to the analysis of the effects of anisotropy.

In this paper we study the outcome of this assumption. We examine the effects of atomic structure of a crystal, by analyzing the phenomenon of acoustic wave propagation in one dimension, thus eliminating the effects of anisotropy. We find that the atomic structure of a crystal plays an essential part in the propagation of acoustic waves, as we pointed out in the Abstract, and its effects cannot be ignored. As a point of reference, we point out the work of Yafei Zeng & Da Chen [8] where they treat a crystal as a continuum, and use the Christoffel equation in conjunction with Newton’s 2nd Law of Motion to solve problem of acoustic waves in a continuum. They call this, the solution to the problem of acoustic waves in a crystal. In fact, they solve the problem of acoustic waves in a continuum. As it transpires, the two are not the same.

In our analysis, when a crystal is represented, as it’s physically correct, by an ordered assembly of point masses (atoms), held together by mutual internal forces, we find that when the atomic motion is assumed to be a continuous function of time and Newton’s 2nd Law is applied, acoustic waves will propagate through the crystal at a speed that depends on the geometry of the initial configuration and, for certain configurations, the wave speed may exceed the speed of light. We also find that there are initial atomic configurations that do not propagate at all.

These findings are physically strange; also, they do not seem to have been observed experimentally. Clearly, the two models, the continuum and the atomic, give rise to different physical outcomes. In a crystal, matter is a digital function of space while, in the continuum, matter is continuous. Thus, the continuum is not a realistic physical model of a crystal. In fact, a material is defined as a crystal when its spatial form is structured, i.e., it is an ordered assembly of point masses. The continuum idealization is reasonable in the static case but gives erroneous results in the dynamic case.

In regard to time, initially we shall proceed with the topic of wave propagation, on the basis of our present understanding of time, i.e., the one-to-one and on-to correspondence between the history of events and the evolving position of the hands of a clock.

Wave Propagation in Crystals

The continuum idealization

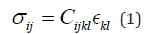

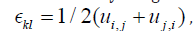

In the context of small strain, we begin the discussion with the continuum idealization [1-9] and give a short derivation. In the literature, the linear elastic law (constitutive equation) is the following, in standard notation:

The stiffness tensor Cijkl has the symmetries:

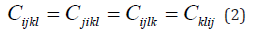

and is positive definite in the sense that:

for all tensors Aij such that Aij > 0 , double bars denoting the Euclidean norm.

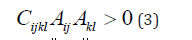

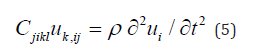

Newton’s law of motion is given by Equation (4).

where the variable t is the standard (clock) time and ρ the reference

density. In light of the strain-displacement gradient relation:

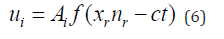

We examine the propagation of plane waves of the form:

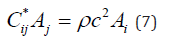

where Ai is the amplitude and nr the direction of propagation and c the wave speed. Substitution in Equation (6) in Equation (5) gives the eigen-equation:

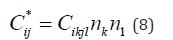

where Cij* is the acoustic tensor given in equation (8):

and is positive definite since  , in light of Equation

(3). Thus C*ij has three positive eigenvalues Cr which are generally

distinct, unless restricted by material symmetries. Thus, in general,

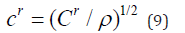

for any direction nr three wave speeds exist given by equation

(9):

, in light of Equation

(3). Thus C*ij has three positive eigenvalues Cr which are generally

distinct, unless restricted by material symmetries. Thus, in general,

for any direction nr three wave speeds exist given by equation

(9):

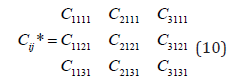

This result is given in the literature on standard continuum mechanics. In a transversely isotropic crystal let x1 be an axis of symmetry and let a wave propagate in the direction x1. Then nr=(1,0,0). In this case:

In transversely isotropic crystals there is no coupling between axial and shear stresses and hence the off-diagonal terms in equation, (10) are zero. The three eigenvalues of C*ij are its diagonal elements. Its eigenvectors, i.e., its eigen-amplitudes Ai are (1,0,0), (0,1,0) and (0,0,1).

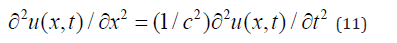

Thus, there is a longitudinal wave with speed (C1111/ρ)1/2, since Ai=(A1,0,0) is in the direction of propagation ni, a transverse (shear) wave with speed (C2121/ρ)1/2 since Ai=(0,A2,0) is normal to ni and second transverse (shear) wave with speed (C3131/ρ)1/2 since Ai=(0,0,A3) and is also normal to ni. In one (axial) dimension, when only the axial stress is present, the elastic wave will propagate at speed c through a thin rod, where c=(E/ρ)1/2, E is Young’s modulus of elasticity and ρ the mass density of the rod. The resulting wave equation is given by Equation (11), where u(x,t) is the axial displacement of the rod.

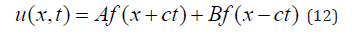

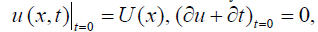

In the case of a continuum representation of an infinite crystal the solution of Equation (11) is given in Equation (12) where the function f(x,t) is bounded in x as well as t:

and A and B are arbitrary constants, otherwise the form

of the function f is arbitrary. When the initial conditions are

, then A=B and Equation

(12) is reduced to Equation (13):

, then A=B and Equation

(12) is reduced to Equation (13):

The initial configuration U(x) splits into two equal parts, one of which travels in the direction of -x and the other in the direction +x at speed c. The above are standard results, found in textbooks on continuum mechanics.

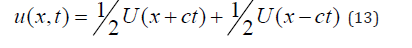

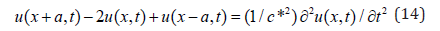

The unidirectional crystal

The equation of motion of an atom in a unidirectional crystal, consisting of equidistant, linearly aligned, like atoms separated by a distance ‘a’, is given by Equation (14), where u(x,t) is a continuous and twice differentiable function of t, which is assumed to be continuous,

and c*2 is equal to K/m, where K is the elastic constant of the atomic bonds and m is the atomic mass.

The values of x are integral multiples of ‘a’, i.e., x=na, n being a positive integer and ‘a’ a positive scalar.

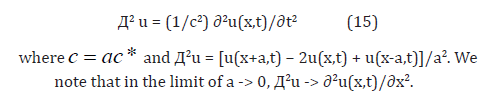

We divide both sides of Equation (14) by a2 to obtain Equation (15):

In solutions of Equation (14), that appear in the literature, the motion of the atoms is periodic, of the generic form of Equation (16), where k is the wave number and ꞷ the frequency:

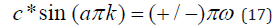

It is found after a short analysis, that the form of u in Equation (16) is a solution of Equation (14) provided that:

Thus, in the case of an atomic crystal ꞷ and k are nonlinearly related, as opposed to the continuum when Д2u = ∂2u(x,t)/∂x2. In this case, they are linearly related, i.e., kc=ꞷ, as a substitution of Equation (16) in Equation (15) will show. This also follows from Equation (17) in the limit of a -> 0, where ac*=c. In crystals, periodic solutions of the type given in Equation (16) exist only when k and ꞷ are related by Equation (17). We are not aware of experiments that confirm or deny Equation (17). This is important because it will be shown that Equation (14) is not the proper equation for the motion of the atoms in a crystal.

Periodic wave solutions of Equation (14)

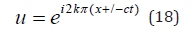

As pointed out, Equation (14) in conjunction with Equation (16) is used broadly in the literature to study oscillatory motions of a crystal. Here we analyze the propagation of periodic acoustic waves in crystals, by means of the function shown in Equation (18)

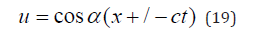

obtained from Equation (16), where c = _ω / k .

A. Speed and wavelength

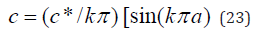

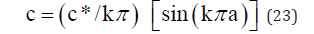

We set á = 2kπ in Equation (17) and thus U = 2Acos(2kπ x) , and following equation (18) we find that the relation for the wave speed c is given by Equation (23).

Since c*2=K/m, where K is the elastic constant of the interatomic bond and m the atomic mass, we note that c depends on these constants as well as the wave number k, i.e., the shape of the wave. An experimental study of this finding would be most useful.

To address the physical issues associated with Equation (18) we choose the real part thereof, shown in Equation (19).

Because the difference/differential equation

(14) is a linear operator O{u(x,t), in the sense that

, a n d

O(Au)=AO(u), and in light of Equation (18), the function in Equation

(20) is also a solution of Equation (14), where A and B are arbitrary

constants. Thus:

, a n d

O(Au)=AO(u), and in light of Equation (18), the function in Equation

(20) is also a solution of Equation (14), where A and B are arbitrary

constants. Thus:

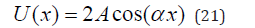

In view of Equation (20), when the initial velocity of the atoms,

i.e., V (x) = ∂u / ∂t at t = 0 is zero, while the initial displacement

of the atoms is  , it then follows that A = B and U(x)

is given by Equation (21), found by setting t=0 in Equation (20), i.e.,

, it then follows that A = B and U(x)

is given by Equation (21), found by setting t=0 in Equation (20), i.e.,

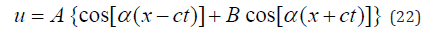

The solution is then given in Equation (22):

We note that the initial stationary wave U =2Acos(αx) splits into two equal parts, one of which, Acos α(x+ct), travels to the left, in the direction -x, while the second, Acos α(x–ct), travels to the right, in the direction +x.

B. Speed and wavelength

If we set á = 2kπ in Equation (17), then ðUx= 2Acos(2k ) and following equation (18) we find that the relation for the wave speed c is given by Equation (23).

Since c*2=K/m, where K is the elastic constant of the interatomic bond and m the atomic mass, we note that c depends on these constants as well as the wave number k, i.e., the shape of the wave. An experimental study of this finding would be most useful.

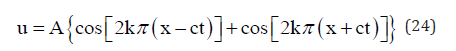

The ‘periodic’ solution is given in Equation (24):

We have not found any experimental data to confirm or deny Equation (23).

Non periodic solutions of Equation (14)

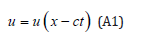

At this point we probe the salient question whether non-periodic functions can be wave-solutions of Equation (14). To this end, we seek the condition that a (non-periodic) wave function u(x–ct) can be a solution of Equation (14).

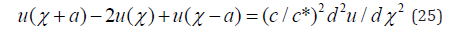

We set x-ct=ꭓ, and substitute u(ꭓ) in Equation (14) to find that the answer is in the affirmative, subject to the condition that u(ꭓ) satisfies Equation (25).

We note that ꭓ is a digital function of x but is continuous and twice differentiable in t. We also note that Equation (25) applies as well to the case where ꭓ=x+ct.

We also note that not all waves can propagate through the crystal, since not all functions u(ꭓ) satisfy Equation (25). For example, the function χ2e−α|χ| ,which is the mathematical form of a pulse, is not a solution of Equation (25), as may be readily verified by substitution. This is in variance with the continuum model of a crystal, in which case all wave functions u(ꭓ) (bounded and twice differentiable in x and t) pass through a crystal unconditionally. It follows that the continuum model of a crystal is not compatible with the atomic model when the equation of motion of an atom is given in terms of Newton’s 2nd Law of Motion in Equation (14).

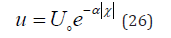

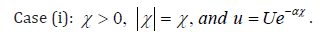

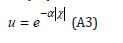

To examine this issue with greater specificity, we solve Equation (14) when u(ꭓ) has the exponential form of Equation (26), where α is a positive scalar and χ = x − ct .

This form ensures that u(x,t) is bounded in the entire domain of x and t.

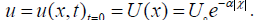

It follows that in the initial configuration

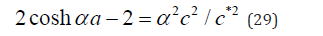

A short analysis, see Appendix A, shows that since c and α are both positive, the algebraic form of u in Equation (26) is a solution of Equation (14) provided that:

Hence, u(x,t) as given in Equation (26), is a non-periodic solution of Equation (14), subject to the constraint of Equation (27).

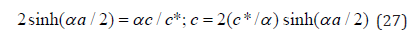

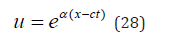

Then u is given by Equation (28):

Substitution of u, given in Equation (28), in Equation (15) yields the condition:

which reduces to Equation (27). We note that c is a positive, increasing function of α. Thus, the form u=U e−α|χ| is a solution of Equation (25) subject to the constraint on the wave speed c posed by Equation (27).

To repeat the salient points of the preceding analysis, there are initial atomic configurations that cannot propagate through the crystal when the displacement function u(x,t) is a continuous and twice differentiable in t. For those that can propagate, the speed c of propagation of the wave, generated by the initial configuration: u=U e−α|χ| is not a purely physical property of the crystal but in addition, it depends on ‘α’, i.e. the rate of spatial decay of the initial configuration 2e−α|x| . Moreover, in view of Equation (27), c increases indefinitely with α to the point where it can exceed the speed of light and beyond, a result that is physically strange. If this were true, we would have discovered asymptotically infinitely fast signals, i.e., asymptotically instant communication at asymptotically infinitely large distances.

To summarize, in an infinite linear crystal, when time is continuous and the atomic motion obeys Newton’s 2nd Law, there exist initial atomic configurations that do not propagate and those that do, propagate at a speed which may exceed the speed of light and beyond. In mathematical terms, given a positive number M, however large, there exist initial configurations such that c >M. We conclude that since Newton’s 2nd Law has withstood the test of time the only remaining option for the resolution of this conundrum is to question the continuity of time.

Discontinuity of Time

Before we proceed, we note that the subject of continuity, or discontinuity, of time has been the topic of discussion through the ages. However, the discussion has been purely speculative, without scientific evidence to support either point of view. Here, using rigorous analysis, we show that in the case of acoustic waves through a crystal, time in discontinuous, in the sense that it changes value in finite increments. To proceed, we note that if we persist in assuming that time is continuous, then since Equation (14) remains the equation of motion of the atoms in a crystal, we will have to posit that the equation of motion is not Newton’s 2nd Law, but some other law, at present unknown.

Since Newton’s 2nd Law has withstood the test of the ages, we are forced to posit that, in the case of this phenomenon at least, time is ‘discontinuous’. We do not find this outcome disturbing, since time is measured (by means of a clock) discontinuously and therefore continuity cannot be proved by experiment using clocks. In fact, a clock is an instrument that generates finite periods of time in perpetuity. Clock time, in effect, is the cumulative sum of small but finite periods. The following is the leading excerpt from a paper by Secada in the Philosophical Review [10] on the continuity of time.

“Historians of philosophy commonly believe that Descartes took time to be made up of temporal atoms. He is thought to have believed in the discontinuity of time and his conception has been characterized as cinematographic. The standard view it that Cartesian atoms have no duration and hence are indivisible.” So, this is not the first time that the continuity of time has been challenged. However, as pointed out previously, discussions on the topic have been purely speculative and without scientific evidence. Here, we prove by rigorous argument that time does, in fact, change discontinuously, albeit in specific physical situations.

To this end, we point out that a device that executes ‘simple

harmonic motion’, is a clock. A reference clock is one such that one

period of its motion is one unit of time. These clocks read time discontinuously

and thus reference time is discrete. It can be used to

read the times of physical events. When we say, colloquially, that an

entity is a function of time, we must observe that this entity, measured

by a clock, is a discrete function (of time), since it is measured

in discrete amounts. On the basis of the above observations, we propose

the following axiom:

a) AXIOM

An evolving physical entity may well be a discrete function of

time unless otherwise inferred. This inference may be the solution

of a differential equation, based on temporal continuity, that depicts

correctly a physical event. The Maxwell equations of electromagnetism

are a case in point. In these equations time is continuous.

Also, Valanis introduced a continuous time, as the fourth dimension

in a 4-dimensional formulation of the elasticity of space-time. He

found that Newton’s 2nd law of motion is the fourth dynamic equilibrium

equation in the 4-dimemsional elastic continuum, when

time remains invariant during deformation.

New Digital Law of Motion

We showed in Section 2.3 that, in a crystal, when the atomic displacements are assumed to be continuous functions of time, the resulting equation of motion, given by Equation (14), gives rise to a wave speed that is physically strange. First, there are initial atomic configurations for which Equation (14) has no solution and second, for those for which there is a solution, the wave speed depends on the geometry of the initial configuration and may exceed the speed of light in vacuo. This is a physically dubious result. It follows therefore from the above discussion, that the atomic displacements in a crystal must be digital functions of time, in the same manner as they are digital functions of space.

Nanomechanical equation of motion

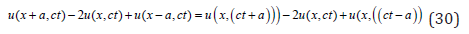

In view of the above discussion, Equation (14) is not mathematically tenable. The time t in Equation (14) must be digital and hence, the second derivative of u(x,t) with respect to t, on the righthand side of Equation (14), does not exist. As a consequence, we replaced it by the second difference. Hence, Equation (14) is replaced by Equation (30), in the manner shown below.

where c2= a2K / m. We observe that Equation (30) is a functional equation since it contains no derivatives.

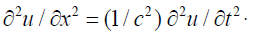

Note that if we divide both sides of Equation (30) by a2 and take

the limit of both sides as a -> 0 we recover the standard wave equation:

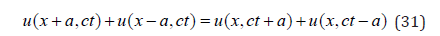

To show that Equation (30) is, in fact, a wave equation for the propagation of acoustic waves in the crystal, it is first simplified into Equation (31):

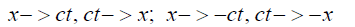

This form, and thus the solution of equation (30), remains invariant with the transformations:

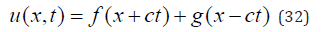

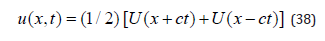

Thus, the variables x and ct must have the same digital properties for the invariance to pertain, i.e., if x is digital then ct must be as well and since x changes by the same finite amounts. Thus, both x and ct change values by finite amounts that are integral multiples of ‘a’. In the case of an infinite crystal, −∞ < x < ∞ , the general wave solution to equation (27) is given by the sum of two functions g and f as in equation (32):

as verified by substitution of Equation (32) in equation (31). We note that Equation (32) is also the solution to partial differential Equation (11)

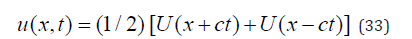

This dual property of the solution given by Equation (32) is a new finding. However, it must be noted that in Equation (11) time is continuous, whereas in Equation (30) time is discontinuous. These are findings that may as yet have repercussions in mechanics and physics. The form of the functions f and g is determined from the initial conditions. When the crystal is initially at rest, in the manner discussed below, then f=g=U, where U(x) is the initial atomic configuration. Then:

Half of the initial configuration, i.e., (1/2) U(x) will propagate to the right of the crystal and the other half to the left. This is a remarkable outcome.

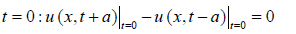

A. Initial Conditions

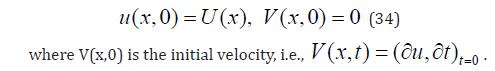

When u(x,t) is assumed to be a continuous function of t, inappropriate for a crystal, then the initial conditions for a crystal initially at rest are:

In the present case where u(x,t) is not continuous in t, the expression

for initial rest is modified. The initial velocity condition is replaced

by the condition that at  . Thus, the ‘condition of rest’ at t = 0 becomes: u(x, a) = (x,−a) . In

light of these statements, the initial conditions become:

. Thus, the ‘condition of rest’ at t = 0 becomes: u(x, a) = (x,−a) . In

light of these statements, the initial conditions become:

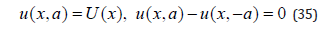

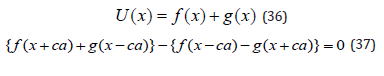

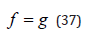

In view of Equations (28) and (35) the constraints on f and g are the following:

Equation (37) is an identity in that it must be true for all x. The solution is:

The solution of Equation (30) is then given in Equation (33), i.e.,

Uniqueness of solution

The solution of Equation (30) is unique. Let u1 and u2 be two different solutions of Equation (30). And let Δu = u2–u1. Since the difference Equation (30) is a linear operator on u(x,t) then Δu is also a solution but with null initial conditions, since both u1 and u2 have the same initial conditions. Thus, if the solution were not unique, and thus Δu was different from zero, and because the initial conditions are null, this would mean that a solution can spontaneously spring into existence and the crystal would spontaneously acquire energy without cause. This, among other things, would violate the principle of conservation of energy. Thus, Δu must be identically zero and the solution of Equation (30) must be unique.

Discussion

We note the previous finding that in a one-dimensional atomic crystal, when the atomic displacement is a continuous function of t and Equation (14) applies, then the speed ‘c’ of the wave generated by the initial configuration, u=2Ue−α|x|, is not a purely physical property of the crystal but, in addition, it depends on ‘α’, i.e. the rate of spatial decay of the initial configuration 2Ue−α|x|. Moreover, ‘c’ increases indefinitely with α, to a point where it may exceed the speed of light in vacuo and beyond, something that is physically dubious.

This finding forces us to abandon the assumption that time is continuous, for this particular phenomenon at least, and to accept the alternative view that time is digital and the atomic motion is also digital in time. It is then found that, when the new digital ‘nanomechanical’ equation of motion, Equation (30), is used, the wave speed depends solely on the physical properties of the crystal, i.e. the elastic constant K of the atomic bonds, the mass m of the constituent atoms and the interatomic distance ‘a’. This is a new and fundamental outcome.

Potential experimental study of the findings

The problem posed above and its solution do not lend themselves easily to an experimental study, because the initial conditions are difficult, though possible, to replicate experimentally. None-theless a lateral tap on a finite thin rod-like crystal will generate a mechanical disturbance, a signal, along the rod. So long as the signal has not reached an end of the rod, its speed may be measured, and a study may be made of the effect of the shape of the signal on its speed of propagation. Because the form of the signal, so generated, is mathematically complex, it may be studied empirically.

However, a great deal may be learned from this experiment. If signals of different forms propagate along the rod at the same speed, irrespective of their shape, this observation, alone, will shed much light on the problem. It would mean that the wave speed does not depend on the shape of the signal and this observation would lend support the nanomechanical formulation of the equation of motion, i.e., Equation (30).

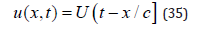

Specifically, if a strain detector (strain gauge) were attached to the end of the rod, the arrival of a signal at the end of the rod would be detected and its time measured and the speed of propagation of the wave would be measured. We note that another experiment presents itself when only one single term of the solution in Equation (32) is used, i.e.,

in the domain 0 < x < ∞ . This solution is a good choice for experimentation since U(t)=u|x=0. The signal U(t) can be generated at x=0 and thus it can be controlled. It will then be seen clearly whether the wave speed c depends on the form of the signal U(t), or not, and whether c is determined solely on the physical constants of the crystal.

Conclusion

In line with our present understanding of physics, the internal atomic motion of a uniaxial crystal, due to external (or internal) disturbances, is given by Equation (14), where time on the righthand side of this equation is continuous. We have shown that the assumption of continuity of time comes into question because the results, following the use of Equation (14), are physically strange. (i) Some initial configurations will not propagate; (ii) for those that do propagate, the resulting speed of the wave depends on the configuration of the wave itself; (iii) in some configurations the wave speed exceeds the speed of light. These findings are physically strange. Also, thus far, they have not been observed. We have done two things to resolve the central issue of wave speed: (1) The assumption of continuity of time was abandoned. Thus, time has been posited as discrete, i.e., it changes in finite intervals; (2) The second derivative in the right-hand side of Equation (14) was replaced by the second difference since, when time is discontinuous, the second time-derivative of atomic displacement does not exist. The initial conditions were adjusted to reflect the discontinuity of time. As a result of these changes, all waves propagate through the crystal at a speed that is determined solely by the physical properties of the crystal, i.e., the elastic constant of the atomic bonds, the mass of the constituent atoms and the interatomic distance.

However, precise experimental work needs to do to answer the questions posed by this article. Specifically, the speed of acoustic waves in crystals needs to be investigated experimentally. Exceedingly high wave speeds in crystals are very unlikely, since they will imply almost instant communication at very large distances. Before we close, we note the issue of representation of crystals by a continuum. This is something that is done routinely, by some authors, in the study of acoustic waves in crystals. See for instance Zhang & Chen and others [1-9], where crystals are treated as continua and are referred to as ‘crystals’ thereafter. This topic was discussed at length earlier in the paper where it was shown that the continuum representation of crystals in the analysis of acoustic waves is inappropriate.

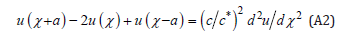

Appendix A

Let:

and let (x – ct) be denoted by the new variable ꭓ, so that u = u(ꭓ). Then, in view of Equation (14):

Let u be given by Equation (A3):

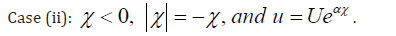

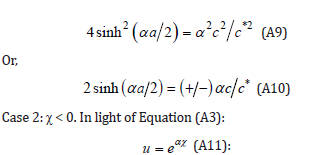

Case 1: ꭓ>0. The in light of Equation (A3):

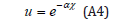

Substitution of u in Equation (13), shown below as Equation (A5):

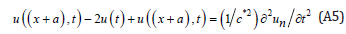

shows that the form of u in Equation (A4), is a solution of Equation (A5), if:

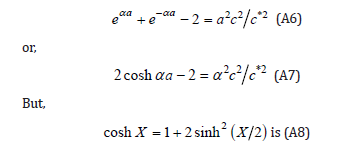

Thus, in light of Equations (A6), (A7) and (A8):

This is as in Case 1 with a change in the sign of α. We note that Equation (A10) remains invariant with a change in the sign of α.

References

- Fedorov FI (1968) Theory of elastic waves in crystals. Plenum Press 1st (edn), New York, USA.

- Musgrave MJP (1970) Crystal acoustics. Introduction to the study of elastic waves and vibrations in crystals. San Francisco, Holden-Day, USA, pp. 1-312.

- Duquesne JY, Perrin B (2001) Interaction of collinear transverse acoustic waves in cubic crystals. Physical Review B 63(6):

- Brugger K (1965) Pure modes for elastic waves in crystals. Journal of Applied Physics 36(3): 759-768.

- Chang ZP (1968) Pure transverse modes for elastic waves in crystals. Journal of Applied Physics 39(12): 5669-5681.

- Farnell GW (1961) Elastic waves in trigonal crystals. Canadian Journal of Physics 39:

- Kochaev AI, Brazhe R A (2011) Pure modes for elastic waves in crystals: Mathematical modeling and search. Acta Mechanica 220: 199-207.

- Zang Y, Chen D (2013) Propagation of acoustic waves in crystals. Multilayer Integrated Film Bulk Acoustic Resonators, pp. 15-19.

- Rosenbaum JF (1988) Bulk acoustic wave theory and devices. Artech House, USA, p. 400.

- Secada JEK (1990) Descartes on time and causality. The Philosophical Review 99(1): 45-72.

© 2026 © Kirk C Valanis. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)