- Submissions

Full Text

Research & Development in Material Science

Impact of TiO2 Nanoparticles on Physicochemical Properties and Breakdown Voltage of African Canarium and African Plum Oils

Jonathan T Ikyumbur1*, Frederick Gbaorun1, John U Ahile2, Nanbol N Gambo3 and Moses V Utile1

1Department of Physics, Benue State University, Nigeria

2Department of Chemistry, Benue State University, Nigeria

3Department of Chemistry, Federal University of Education, Nigeria

*Corresponding author:Jonathan T Ikyumbur, Department of Physics, Benue State University, Makurdi, Benue State, Nigeria

Submission: June 27, 2025;Published: August 06, 2025

ISSN: 2576-8840 Volume 22 Issue 1

Abstract

The Breakdown Voltage (BDV) and the physicochemical properties of nanofluids based on African Canarium (Canarium schweinfurthii) and African plum (Dacryodes edulis) were evaluated to ascertain their suitability as transformer oils. The fruits were purchased from the local markets and extracted using the Soxhlet apparatus. The oils were then purified to remove any impurities that would make them unsuitable for electrical insulation in the high-voltage power equipment. The oil samples were then divided into five 100 ml samples each, and four of them were treated with TiO2 nanoparticles at 0.01wt% to 0.04wt% TiO2 nanoparticles, respectively. The BDV of the pure ester were determined to serve as the baseline, and the BDV of the samples treated with nanoparticles were measured. The samples treated with 0.03wt% TiO2NPs recorded the highest BDV of 59.40kV at 60 ℃. The significant enhancement in the BDV of the Canarium and Dacryodes-based nanofluids recorded in this study is influenced by multiple mechanisms (such as trapping free electrons by nanoparticles, Maxwell-Wagner-Sillars polarization, and suppression of streamer initiation). The key physicochemical properties, such as density, viscosity, sludge formation, moisture content, acidity, flash point, and pour point of this mixture (i.e., 0.03wt% TiO2NPs) were also determined. These key physicochemical properties were within the acceptable standard of IEC and IEEE, suggesting that the properties are technically viable to replace conventional mineral oil. The results of the physicochemical properties also demonstrate that the Canarium and Dacryodes-based nanofluids are safe, thermally stable, electrically reliable, and suitable for long-term use in high-power systems.

Keywords:Breakdown voltage; Physicochemical properties; Canarium-based nanofluids; Dacryodes-based nanofluids

Introduction

Transformer oils are highly refined mineral oils used as an insulating and cooling medium in transformers, tap changers, circuit breakers, and other electrical equipment. The oil prevents electrical discharges between internal components, dissipates heat generated during operation, helps extinguish electric arcs, coats internal parts, and prevents corrosion and oxidation. While vital for cooling and insulation, transformer oil can degrade over time due to electrical, thermal, and environmental stresses, reducing dielectric strength, overheating, and even transformer failures. This degradation is often caused by contamination with moisture, particles, and impurities, as well as the effects of high temperatures and oxidation [1]. There is a shift towards alternative transformer oils driven by a mix of factors (i.e., technical, environmental, and safety) related to traditional mineral-based transformer oil.

Growing concerns over fire safety, environmental impact, and the non-renewability of traditional mineral oil in transformers have necessitated the search for alternative oils used in transformers. Alternative transformer oils, such as synthetic and natural esters (vegetable-based oils), offer improved fire resistance, biodegradability, and sustainability [2-5]. Mineral oil is petroleumbased and non-biodegradable; therefore, the oil contaminates soil and water in the case of leakage or spillage. The cleanup is usually expensive and highly regulated in many countries [6]. Mineral oil is also characterized by a moderate flash point of 140 ℃ and can ignite when exposed to flame or spark at this high temperature or higher. During transformer faults, arcing or overheating can cause mineral oil to reach its flash point, leading to ignition and potentially a fire [7,8].

Vegetable-based (natural ester) oils are increasingly used in transformers as an alternative to traditional mineral oils, but they come with both benefits and challenges [9-11]. The problems associated with vegetable-based oils are high viscosity, oxidation stability, higher cost, limited proven track record, moisture sensitivity, and compatibility with materials [12,13]. Natural ester oils are generally more viscous than mineral oils, especially at low temperatures. They are prone to oxidation, which can lead to acid formation and sludge. This can degrade the insulating properties of the oil unless proper oxygen barriers or sealed designs are used. Despite these disadvantages, the natural ester oils are highly biodegradable and are characterized by their environmental friendliness, high fire point, excellent dielectric strength, and moisture tolerance. Research has shown that using nanoparticles such as SnO2, Fe2O3, ZnO, TiO2, CuO, or their hybrid [14] can help mitigate most of these challenges.

It has been reported that titanium dioxide TiO2 enhances the performance of natural ester oils [15]. The TiO2 improves the dielectric strength of the natural ester oils by trapping and slowing down free electrons, which helps prevent premature electrical breakdown [16,17]. This behaviour exhibited by the TiO2 enhances the AC and impulse breakdown voltage, making the fluid more robust under electrical stress [18]. Induranga et al. [19] reported improvement in heat transfer when transformer oil and coconut oils were treated with TiO2 nanoparticles. This treatment with nanoparticles can help mitigate the issues of high viscosity and poor cooling, as the consequences of the TiO2 nanoparticles additive to natural oil. Other properties of TiO2 nanoparticles include their ability to inhibit oxidation reactions in natural ester oils. This factor helps improve oxidation stability and extend the oil’s lifespan. The TiO2 can also absorb water or alter the moisture equilibrium between the oil and the paper, resulting in a reduction in the rate of hydrolysis and potentially slowing down insulation ageing [20].

Transformer oil-based nanofluids are advanced insulating and cooling fluid used in electrical power equipment, primarily transformers [21]. These fluids are conventional transformer oils, either mineral oil or synthetic ester-based, that have been enhanced by dispersing nanoparticles to improve their thermal and electrical properties [22]. This work examines the impact of TiO2 nanoparticles on the physicochemical properties and breakdown voltage of African Canarium (Canarium schweinfurthii) and African Plum (Dacryodes edulis) Oils for their suitability as transformer oil.

Theoretical Framework

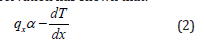

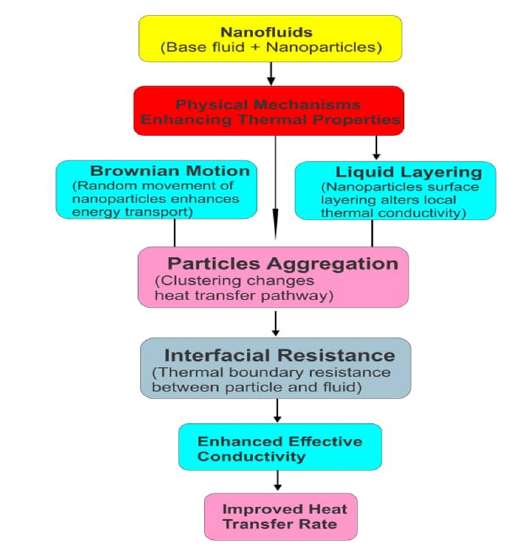

Nanofluids are engineered by colloidal suspensions of nanoparticles, often less than 100nm, in a base fluid like water, ethylene glycol, or oil [23,24]. The physical mechanisms, such as thermal conductivity, Brownian motion, thermophoresis, diffusiophoresis, and viscosity changes, enhance heat transfer in nanofluids [25-28]. These physical mechanisms are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 portrays the synergy between multiple physical mechanisms that make nanofluids so interesting and effective, especially in heat transfer applications. Figure 1 illustrates how thermal conductivity can improve the ability of the fluid to conduct heat. The physical mechanisms involved are that nanoparticles have higher thermal conductivity than the base fluid [29,30]. In this case, the thermal conductivity acts as a “thermal bridge” for heat transfer between the fluid molecules [31]. As shown in Figure 1, the thermal conductivity enhancement is indirectly influenced by Brownian motion, thermophoresis, and clustering of particles. The Brownian motion can be referred to as the random motion of nanoparticles due to collisions with base fluid molecules. This motion causes the micro-convection within the fluid and disrupts thermal boundary layers, which increases local heat transfer. Research has shown that Brownian motion is more significant at smaller particle sizes and higher temperatures [32]. It also enhances thermal conductivity and affects viscosity due to increases in particle-fluid interactions.

The heat conduction, as shown in Figure 1, refers to energy transfer due to temperature gradients without any bulk motion of the fluid. In fluids, molecules transport thermal energy by collisions and interactions. This microscopic activity is modelled macroscopically by Fourier’s law. The law states that the heat flux qx is the rate at which heat transfer per unit area:

where ΔQ is the amount of heat conducted in the time Δt , A is the cross-sectional area, and Δt is the small-time interval. Again, experimental observation has shown that:

The negative sign indicates that heat flows from regions of high temperature to lower temperature. If we introduced the constant of proportionality in equation (2), we have

Equation (3) is Fourier’s law in one dimension. The general form of equation (3) in three dimensions is:

Applying the principle of conservation of energy in the control volume, the internal energy change rate will be equal to the net heat flow into the volume. For a homogeneous, isotropic material with constant thermal properties, conservation of energy in differential form is:

where ρ is the fluid density (kg/m3), p c It is the specific heat

capacity at constant pressure (Jkg−1k−1) and  It is the rate of change of temperature with time.

It is the rate of change of temperature with time.

Substituting equation (5) into equation (4) gives

where  is the thermal diffusivity (m2/s) equation (7) is

the heat conduction equation known as the Fourier heat equation.

The equation (7) still holds in nanofluids, i.e.,

is the thermal diffusivity (m2/s) equation (7) is

the heat conduction equation known as the Fourier heat equation.

The equation (7) still holds in nanofluids, i.e.,

The key difference is that the effective thermal conductivity

keff It is enhanced due to nanoparticles. Therefore,

. increases.

increases.

Figure 1:The physical mechanisms in nanofluids.

Methods

Procedure for the extraction of oil using the soxhlet apparatus

The ripe fruits from African Canarium (Canarium schweinfurthii) and African plum (Dacryodes edulis) were purchased in Agbo market in Vandrikya local area of Benue State and Mangu market in Plateau State, Nigeria (Figure 2 & 3).

The fruits were thoroughly cleaned of any forms of dirt and foreign material. The fruits were allowed to decay so that the fruit’s outer pulp and the inner seed-kernel of the African Canarium could be separated. Similarly, the outer skin, pulpy flesh and the inner seeds of the African plum were separated. The outer pulp from the African Canarium and the skin pulp from the African plum were sun-dried. The outer pulp from the African Canarium and the skin pulp from the African plum were crushed and separated into powder using the mortar and pestle to increase the surface area. The powdered pulps were securely and loosely packed into the improvised thimble for easy passage of the solvent. The packed thimble was then introduced into the extraction chamber.

Figure 2:The ripe fruits of the African canarium (Canarium schweinfurthii).

Figure 3:The ripe fruits of the African plum (Dacryodes edulis).

The Soxhlet apparatus was set up by connecting the extraction chamber containing the powdered pulps to the round-bottom flask containing 500cm3 of n-hexane. The condenser was attached to the top of the extraction chamber and was then connected to a coldwater supply for efficient condensation of the vaporized solvent. The round-bottom flask was placed on the heating mantle, and the solvent was heated to its boiling point (i.e. 68 to 70° ℃). As the solvent vaporized, it ascended the apparatus. Then it condensed in the condenser before dripping back down into the extraction chamber, where it dissolved the oil as it made contact with the powdered pulps. This cycle of solvent evaporation, condensation, and dripping continued repeatedly, with the solvent dissolving the oil from the pulps. The solvent was collected in the extraction chamber until it reached the point where the oil-solvent mixture flowed back into the round-bottom flask. This process was allowed to continue for several cycles (usually 4-6 hours). The extraction was taken to be complete when the solvent passing through the thimble returned clear, indicating no more oil was being extracted.

The round-bottom flask was disconnected from the Soxhlet apparatus, and the solvent-oil mixture was poured into a beaker. Finally, the oil was recovered from the mixture with the aid of a rotary evaporator. The extracted oil was collected and stored in a clean airtight container, away from light and heat, to prevent oxidation and degradation. The percentage recovery was used instead of percentage yield because no chemical reaction took place during the extraction. It was calculated using equation (9):

For the 18.5g recovery weight from African canarium (Canarium schweinfurthii) and 55g weight of the pulps, the percentage recovered was 33.64%. Meanwhile, 28g of the recovery weight from African plum (Dacryodes edulis) and the 60g of pulp weight gives a recovery of 46.67%.

Purification of based oils

The extracted oil from ripe African Canarium (Canarium schweinfurthii) and African plum (Dacryodes edulis) was then purified to remove any impurities that would make them unsuitable for electrical insulation in high-voltage power equipment. The purification processes, like degumming, bleaching and deodorization of the African canarium oil (ACO) and African plum oil (APO), were done separately. 200ml of the base oil was heated in a 500ml conical flask to a temperature of 70 ℃. The aqueous citric acid of 1.5ml was then added gently. The mixture was thoroughly mixed with a magnetic stirrer for 15 minutes at 800rpm, and the oil was then decanted gently. Thereafter, 4ml of NaOH solution was gently added, and the mixture was magnetically stirred at 400rpm for 15 minutes. The samples were washed with warm distilled water and then dried in a vacuum ovum at 85 ℃ for 50mins to reduce the water content in the oil. Silica gel of 2g was added to the mixture at 70 ℃ and it was vigorously agitated for 30 minutes at 300rpm to prevent it from settling out. Fuller’s earth or Bleaching clay of 5g was added to the oil for bleaching and magnetically stirred for 40 minutes at 95 °C. The sample was then filtered using Whatman No. 5 and No. 1 and washed with distilled water 3 times. The sample was dried in a vacuum oven at 85 °C for 50 minutes to reduce the water content in the oil.

Esterification of purified oil samples

A 100g for each oil sample was poured into a 250ml conical flask and placed on a hot plate. A thermometer was attached to a retort stand and introduced into the oil. The temperature was kept constant at 60 °C and stirred mechanically at 800rpm. To reduce the % FFA of the oil, the weight of methanol to be added was determined according to Al-Sakkari et al. [33]. A mole ratio of 1:6 of oil to methanol was required for esterification. For example, 100g of African Canarium oil requires 23.5g of methanol. Therefore, the mixture of 23.5g of methanol and 2g (2%) of concentrated tetraoxosulphate (IV) acid was then transferred slowly into the oil in the conical flask. The mixture was then stirred for about 1 hour at 60 °C to esterify. The mixture was allowed to stand for 1 hour, and the methanol-water, which rose to the top, was decanted. The bottom fraction was then pre-treated or esterified with oil, and the FFA was determined again to ensure that its FFA is less than 5% before transesterification. A similar procedure was repeated for African plum oil.

Oil transesterification process

A 400g of the oil was introduced into the flat-bottom flask with a magnetic stirrer, and the sample was allowed to heat up to 60 °C while magnetic stirring was continuous. The potassium hydroxide (KOH) was used as a catalyst in the oil transesterification process because of its effectiveness and efficiency [34,35]. 6.8g of KOH was dissolved completely in 83.9g of pure methanol to form potassium methoxide solutions, and the mixture was stirred. The solution was then added to the oil and stirred for 1 hour, and the mixture was transferred to a separating funnel. The methyl ester formed was separated from the glycerol, and the ester was washed with warm water to remove any remaining KOH. The oven dried with the remaining moisture for 2-3 hours.

Functionalization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles

The titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles were prepared using a two-step method. The Peppas et al. [36] preparation method was adopted. 5g of the nanoparticles were functionalized by dispersing in 100mL of ethanol at 60o °C and stirred for 1 hour with a magnetic stirrer. For proper dispersion, 0.250ml of oleic acid was added to the ethanol-nanoparticles mixture for surface coating and stirred for 2 hours. The mixture was therefore centrifuged to separate ethanol and oleic acid from the nanoparticles. The treated nanoparticles were collected, washed with ethanol, and oven dried for 2 hours at 80 °C to remove excess ethanol.

Synthesis of nanofluids from esters

The nanofluids were prepared by dispersing treated, surfacemodified or oleic-coated nanoparticles in 0.01wt% to 0.04wt% with 0.01 steps in the oil samples and stirred using a magnetic stirrer for 15-30 minutes (Table 1).

Table 1:Description of the samples.

Measurement of physicochemical properties

The key physicochemical properties of Canarium schweinfurthii and Dacryodes edulis Oils’ nanofluids are evaluated to determine their suitability, performance, and longevity. The following key properties were measured:

Density measurement: The cylinders were thoroughly washed and properly dried. They were then filled to 1000ml with esterified Canarium and Dacryodes nanofluid oils. According to Gen et al. [37], the temperature was kept constant at 40 ℃ throughout the experiment to determine the densities of oils because density is temperature-dependent for most liquids (including oil). Therefore, the temperature was controlled to obtain accurate and reproducible density measurements. The densities of Canarium and Dacryodes nanofluids are recorded in Table 2.

Table 2:Physicochemical properties.

Viscosity measurement: The DV-E Brookfield viscometer machine, shown in Figure 4, was used to measure the oil’s viscosity. The cylinder was filled to 500ml with oil, and the temperature of the oil in the cylinder was maintained at 40 ℃. Maintaining a constant temperature of the natural ester during the measurement ensured accuracy and comparability. Natural esters, especially those used as insulating fluids, have a small temperature variation that can lead to large changes in the viscosity [38,39]. The viscometer machine was powered ON, and four spindles were clamped on the rotational axis of the viscometer. The spindle type was set to spindle four (4), and the speed of the spindle at 60 RPM (revolutions per minute). The spindle was deep down into the oil sample under measurement up to the graduated point of the spindle before pressing the menu button to set the spindle rotating. The viscosity of Canarium and Dacryodes-nanofluids was determined according to the ISO standard [40]. Equation 10 was used to obtain the viscosity values in centistokes

Figure 4:The DV-E Brookfield viscometer used for experimental measurement of oils viscosities.

Measurement of the oil flash point: The PM-4 Petrotest flash point machine was powered ON to measure the flash point, and oil was poured into the flashing cup to the graduated mark and closed with the cover. The cup was clamped into the heating compartment of the machine, and a mercury thermometer was inserted into its compartment in the flash cup before pressing the run button for both the heating and spinning. The experimental setup is as shown in Figure 5, and the centrifuge cup is depicted in Figure 6. The gas was switched ON and the flashlight was ignited. As the temperature was rising, the flashlight was deepened to the volatile outlet of the flash cup at an interval of 2 to 3 minutes until the light went out (flashed). The temperature at which the oil sample flashed was recorded immediately on the thermometer and recorded in Table 2.

Figure 5:Experimental setup for flash point measurement using the PM-4 Petrotest flash point machine.

Figure 6:The flash point cup inside the PM-4 Petrotest flash point machine used for housing the spinning fluid.

Measurement of pour point: The ASTM D97 method was used to measure the cold-temperature performance of the insulating oils. 10ml of the oil samples were kept in a glass tube and fitted with a cork and thermometer. These samples were kept in the cabinet until they became solid, and the temperature at which each sample became solid was taken. The temperature readings were then corrected by a factor of +3 according to Egbuna et al. [41].

Determination of the oil moisture content: To determine the moisture content, an empty crucible/cup was weighed on a weighing balance and the value was recorded as W2. 0.5ml of the oil sample was filled into the crucible and recorded as W1. The weighed oil sample was placed into a vacuum oven as shown in Figure 5, operating at a temperature of 120 ℃ for one hour. The sample was removed and inserted into a desiccator for about 5-10 minutes to cool. The cooled sample was then weighed, and the recorded value was again taken to be W3. The percentage moisture content of the oil was calculated using equation 11:

The crucible was then filled with 2ml of the oil, and the above procedures were repeated and recorded in Table 2, Figure 7.

Figure 7:The F-STREEM Vacuum Oven for demoisturizing water from the oil samples during the determination of moisture content.

Determination of the oil sludge: The FUNKE-GERBER Centrifuge Machine, shown in Figure 8, was used to measure the amount of sludge in the oil. This was carried out by weighing an empty, clean test tube as W2. and also weighed 20g of the oil sample into a test tube, and then centrifuged the oil sample in the centrifuge machine and powered the centrifuge to set the sample spinning for 15 minutes. The spinning centrifuge machine with the sample on it was stopped, the sample and decanted the sample off the test tube completely and again weighed as W3. The percentage of sludge was mathematically calculated using the formula:

Figure 8:The FUNKE-GERBER Centrifuge Machine used in the determination of sludge.

Free fatty acid (acidity) measurement: To measure the free fatty acid content in the selected oil sample, 0.1N of caustic soda (NaOH) was prepared based on the IEC standard [42]. More than 50mL of methylated spirit was measured, and two to three drops of phenolphthalein indicator were added to give a light pink colouration. A 50g sample of the oil was again weighed into a beaker, and the sample was heated on a heating panel. 50ml of the mixture of methylated spirit and indicator was added and titrated against 0.1N of caustic soda (NaOH) until a light pink colouration, which is the endpoint and represents the titrated value, was reached. The FFA was calculated using the relationship below:

Where T is the titer value reached, N is the normality of NaOH, W1. is the weight of the oil sample, and 28.2 is known as the Oleic constant. The results for the free fatty acid content of the oil are reported in Table 2.

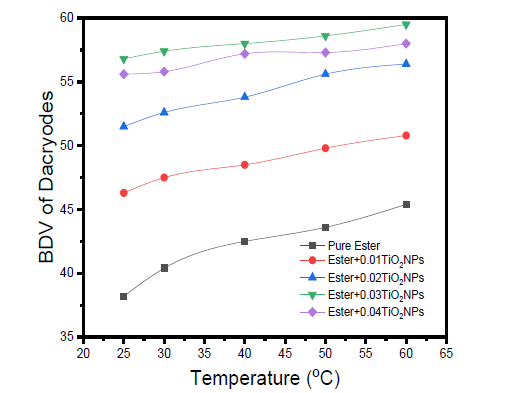

Measurement of the breakdown voltage: The breakdown voltage of the oils was determined by measuring 100ml of the oil in a measuring cup containing an electrode gap of 2.5mm according to (IEC 60247, 1978) [43]. The oil filled in the vessel of the MEGGER 60KV oil tester machine, shown in Figure 9. The machine was switched ON and allowed to steam for about 1-2 minutes, and five breakdown voltages of pure Canarium and Dacryodes were taken at different temperatures. A similar procedure was repeated for ester+%wt TiO2 NPs, and the average breakdown voltage (BDV) of the Canarium was recorded in Table 3 and the Dacryodes in Table 4.

Figure 9:The MEGGER 60 KV Oil Tester Machine used for measuring transformer oil dielectric constant.

Table 3:The breakdown voltage of Canarium schweinfurthii-based nanofluids (kV).

Table 4:The breakdown voltage of Dacryodes edulis based nanofluids (kV).

Results and Discussion

Breakdown voltage of canarium and dacryodes-based nanofluids

The breakdown voltage (BDV) of pure Canarium and Dacryodes and their respective base-nanofluids at different weights of TiO2 nanoparticles are presented in Table 3 & 4, respectively. The results of the BVD of natural esters increase as the temperature rises from 25 °C to 60 °C. This could be as a result of the decrease in viscosity, a few space-charges accumulation and faster bubble dissipation in the oils at higher temperatures. It has been reported that bubbles cause localized field intensification and dissipate faster at higher temperatures [44-46]. The results also increased significantly with the addition of TiO2 nanoparticles and rising temperature. The increment in BDV as a result of the presence of nanoparticles may be due to electron scavenging and creation of Maxwell-Wagner-Sillar (MWS) polarization at the interface between the high-permittivity nanoparticles and the low-permittivity of the oil.

The BDV of ester+0.01wt% TiO2 was higher than their corresponding pure esters and again increased with an increase in temperature. This can be attributed to combinations of electrical, thermal, and nanoscale interfacial mechanisms. Research has shown that TiO2 nanoparticles can trap charge, and when an electric field is applied, free electrons, which usually initiate streamer formation, are captured by the presence of the nanoparticles [47]. This behaviour potential slows down or suppresses the streamer propagation and delays breakdown. It has also been reported that the interface between TiO2 nanoparticles and the ester oil creates Maxwell-Wagner-Sillars (MWS) polarization. This MWS polarization, especially when TiO2 nanoparticles are introduced into the oil, can increase the dielectric strength of the ester oil [48,49]. The thermal energy experienced by the oil helps maintain or even improve the dispersion of the nanoparticles, particularly at low concentrations of 0.01wt%.

Physicochemical properties of canarium and dacryodesbased nanofluids

The key physicochemical properties were measured at the mixture of ester + 0.03wt% TiO2NPs because this mixture gave the best breakdown voltage (Figure 10 & 11). These key properties were evaluated for their suitability as base fluids for nano fluids in transformer insulation and the results obtained are presented in Table 2.

Figure 10:The BDV of pure canarium and canarium+TiO2 NPs at different temperatures.

Figure 11:The BDV of pure dacryodes and dacryodes+TiO2 NPs at different temperatures.

In Table 2, the density of Canarium-based oil + 0.03wt% TiO2NPs and that of Dacryodes-based oil+ 0.03 wt% TiO2NPs were 840kg/m3 and 860kg/m3 respectively. These densities fall within the range for light vegetable oils [51], suggesting that the base oils (Canarium schweinfurthirthii and Dacryodes edulis) are light and less viscous. The enhancement in the density of the oils may be due to the addition of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. In the separate reports by Baruah et al. [52] and Rafiqi et al. [53], nanoparticles are denser than the oil, and their presence in the base oil increases the overall mass per unit volume. Hence, the interaction between the nanoparticles and the oil molecules can significantly contribute to the slight increase in the effective density of the nanofluids.

The viscosities at the base oils +0.03wt% TiO2NPs were 25cSt and 30cSt, respectively, and are significant because they indicate a balanced flow of the oils and good dielectric cooling properties. The viscosities of these nanofluids are consistent with the work of Marino et al. [54]. They opined that these viscosities are high enough to reduce the sedimentation and indicate that the NPs are well-dispersed in the base oils. Research has shown that welldispersed nanofluids often exhibit consistent viscosity, density, and acidity, and can maintain more uniform properties throughout the fluid [55,56].

The sludge formation at the base oils +0.03wt% TiO2NPs was zero. This signifies that the oxidative is stable, clean, and has long-term usability. Sludge forms whenever the oils are oxidized, especially under heat and in the presence of moisture. The zero sludge means the oil resists oxidative degradation. This may be because nanoparticles and probably antioxidants help inhibit oxidation. The moisture content of the same mixture was 0.01% and 0.02%, respectively, suggesting minimal risk of agglomeration due to water-mediated clustering. This showed a stable zeta potential (i.e., the electrostatic repulsion between NPs) and can also mean a longer shelf life of the nanofluids. The acidity value of 0.001 and 0.002mgNaOH/kg was recorded for Canarium and Dacryodes, respectively may be due to the addition of nanoparticles to the base oils. The acidity value is significant because it provides excellent chemical stability and suitability for high-voltage insulation systems.

The flash of Canarium-based nanofluid was 255 °C, and that of Dacryodes-based nanofluid was 248 °C, respectively. This shows that Canarium-based nanofluid possesses excellent thermal and fire resistance. The flash point of 255 °C is within the IEC and IEEE standard of above 250 °C flash point in urban or other sensitive installations. However, the flash point of 248 °C is below the IEC and IEEE standards [57]. This may be likely because Dacryodesbased nanofluids contain more low-molecular-weight compounds, shorter-chain fatty acids, and are slightly thermally unstable than Canarium-based nanofluid. The pour point of -8 ℃ was recorded for Canarium-based nanofluid and -4 °C for Dacryodes-based nanofluids. Again, Dacryodes-based nanofluid was characterized with a moderate pour point. This could be because Dacryodesbased nanofluid contains significant levels of saturated fatty acids, which tend to crystallize at low temperatures.

Conclusion

This work explored the possibility of using Canarium and Dacryodes-based nanofluids by evaluating their breakdown voltage (BDV) and physicochemical properties. The BDV and physicochemical properties of the respective nanofluids showed that the BDV of Canarium and Dacryodes-based nanofluids were significantly enhanced by adding TiO2 nanoparticles (Figure 10 & 11). The much-improved BDVs can be attributed to multiple mechanisms. For instance, adding the TiO2 nanoparticles to the Canarium and Dacryodes-based oils helps trap the free electrons, slows down the streamer propagations, causes local field smoothing, reduces field intensity spikes, and hinders electron avalanche formation.

The low moisture content recorded in this work, as shown in Table 4, was due to the absorption and dispersion of TiO2 nanoparticles. Research has shown that nanoparticles absorb and immobilize water molecules [58,59]. A well-dispersed nanofluids also prevent water from forming conductive micro-paths. The work also recorded a low acidity (Table 4), which can be attributed to the antioxidant and catalytic effects of the TiO2 nanoparticles. The NPs act as radical scavengers, which slow down oxidation in the base oils. The zero-sludge formation obtained in this work is also due to the introduction of nanoparticles that help the oil to resist thermal degradation and sludge-producing polymerization reactions.

The high flash point, which determines the low volatility of the ester oils and additives present in the Canarium and Dacryodesbased nanofluids, is presented in Table 2. This high flash point is due to the natural esters and TiO2 nanoparticles, because natural esters and TiO2 nanoparticles have inherently high boiling points that can result in high flash points. The low pour point observed in this work is largely influenced by molecular structure. Esters have branched chains that lower crystallization temperatures. Research has shown that nanoparticles disrupt the wax crystals in the natural esters and the nanoparticles interface with the formation of the paraffinic crystals, thereby lowering the pour point [60]. They explained that this can be achieved through different mechanisms, like heterogeneous nucleation, where nanoparticles act as nucleation sites, modifying the morphology and size of wax crystals, and inhibiting crystal growth and aggregation. The viscosity of the oil is also tuned by nano-oil interaction. The interaction laid a foundation for nanoparticles to form a thin, ordered layer of oil molecules at their surface, affecting the nanofluids’ overall flow behaviour.

Acknowledgment

We wish to acknowledge the support of the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND) for sponsoring this research.

References

- Tiwari R, Agrawal PS, Belkhode PN, Ruatpuia JVL, Rokhum SL (2024) Hazardous effects of waste transformer oil and its prevention: A review. Next Sustainability 3: 100026.

- Ghislain MM, Gerard OB, Emeric TN, Adolphe MI (2022) Improvement of environmental characteristics of natural monoesters for use as insulating liquid in power transformers. Environ Techn Inno 27: 102784.

- Das AK, ChShill D, Chatterjee S (2022) Coconut oil for utility transformers-environmental safety and sustainability perspective. Renew Sustain Energy Reviews 164: 112572.

- Shen Z, Wang F, Wang Z, Li J (2021) A critical review of plant-based insulating fluids for transformer: 30-year development. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 141: 110783.

- Kumar A (2022) Natural ester oil is a sustainable insulation oil to mineral oil for power transformer industries and electric power system. Inter’l Conf Sustain Eng Techn 1E:120.

- Chuberre B, Aravilskaia E, Bieber T, Barbaud A (2019) Mineral oils and waxes in cosmetics: An overview mainly based on the current European regulations and the safety profile of these compounds. J Europ Acad Derm Vener 33(7): 5-14.

- Siddique A, Adnan M, Aslam W, Qamar HGM, Aslam MN, et al. (2024) Up-gradation of the dielectric, physical and chemical properties of cottonseed-based, non-edible green nanofluids as sustainable alternative for high-voltage equipment’s insulation fluids. Heliyon 10(7): e28352.

- El-Harbawi M, Al-Mubaddel F (2020) Risk of fire and explosion in electrical substations due to the formation of flammable mixtures. Scientific Reports 10: 6295.

- Rafiq M, Lv YZ, Zhou Y, Ma KB, Wang W, et al. (2015) Use of vegetable oils as transformer oils- A review. Renew Sustain Energy Reviews 52: 308-324.

- Meira M, Ruschetti C, Alvarez R, Catalano L, Verucchi C (2018) Dissolved gas analysis differences between natural esters and mineral oils used in power transformers: A review. IET Journals 13(24): 5441- 5448.

- Oparanti SO, Rao UM, Fafana I (2023) Natural esters for green transformers: Challenges and keys for improved serviceability. Energies 16(1): 61.

- Uppar R, Dinesha P, Kumar SA (2023) critical review on vegetable oil-based bio-lubricants: preparation, characterization and challenges. Environ Dev Sustain 25: 9011-9046.

- Murru C, Badia-Laino R, Diaz-Garcia ME (2021) Oxidation stability of vegetable oil-based lubricant. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 9(4): 1454-1476.

- Rafiq M, Shafique M, Azam A, Ateeq M (2021) Transformer oil-based nanofluid: The application of nanomaterials on thermal, electrical and physicochemical properties of liquid insulation: A review. Ain Shams Eng J 12(1): 555-576.

- Saenkhumwong W, Suksri A (2017) The improve dielectric properties of natural ester oil by ZnO and TiO2 Eng Appl. Research 44(3): 148-153.

- Chen B, Yang J, Li H, Su Z, Chen, R, et al. (2023) Electrical properties enhancement of natural ester insulating oil by interfacial interaction between KH550-TiO2 and oil molecules. Surface & Interfaces 42: 103441.

- Das AK (2024) Exploring SiO2, TiO2, and ZnO nanoparticles in coconut oil and mineral oil under changing environmental conditions. J Mole Liquids 397: 124168.

- Chakraborty B, Raj KY, Pradhan AK, Chatterjee B, Chakravorti S (2021) Investigation of dielectric properties of TiO2 and Al2O3 nanofluids by frequency domain spectroscopy at different temperatures. J Mole Liquids 330: 115642.

- Induranga A, Galpaya C, Vithanage V, Koswattage KR (2023) Thermal properties of TiO2 nanoparticles-treated transformer oil and coconut oil. Energies: 17(1): 49.

- Wang Y, Zeng Z, Gao M, Huang Z (2021) Hydrothermal ageing characteristics of silicon-modified aging -resistant epoxy resin insulating material. Polymer 13(13): 2145.

- Sorte S, Salgado A, Monteiro AF, Ventura D, Martins N, et al. (2025) Advancing power transformer cooling: The role of fluids & nanofluids- A comprehensive review. Material 18(5): 923.

- Hussain M, Mir FA, Ansari MA (2022) Nanofluids transformer oil for cooling and insulating applications: A brief review. Appl Surf Sc Advan 8: 100223.

- Pinto RV, Fiorelli FAS (2016) Review of the mechanisms responsible for heat transfer enhancement using nanofluids. Appl Therm Eng 108: 720-739.

- Khattak MA, Mukhtar A, Kamran AS (2020) Application of nanofluids as coolant in heat exchanger: A review. J Advan Research in Maters Sc 66(1): 8-12.

- Awais M, Bhuiyan AA, Salehin S, Ehsan MM, Khan B (2021) Synthesis, heat transport mechanisms and thermophysical properties of nanofluids: Critical overview. Int J Thermofluids 10: 100086.

- Shen M, Liu Y, Yin Q, Zhang H, Chen H (2024) Enhanced thermal and mass diffusion in maxwell nanofluid: A fractional brownian motion model. Fractal & Fractional 8: 491.

- Gupta A, Kumar R (2007) Role of Brownian motion on the thermal conductivity enhancement of nanofluids. Appl Phys Letts 91: 223102.

- Lattini G (2017) Thermophysical properties of fluids: Dynamic viscosity and thermal conductivity. Journal of Physics: Conf Series 923: 012001.

- Guan H, Su Q, Wang R, Huang L, Shao O, et al. (2023) Why can hybrid nanofluid improve thermal conductivity more? A molecular dynamics simulation. J Mole Liquids 372: 121178.

- Kalsi S, Kumar S, Kumar A, Alam T, Dobrota D (2023) Thermophysical properties of nanofluids and their potential applications in heat transfer enhancement: A review. Arabian J Chem 16(11): 105272.

- Kiruba R, Jeevaraj AKS (2023) Rheological characteristics and thermal studies of EG- based CU: ZnO hybrid nanofluid for enhanced heat transfer efficiency. Chem Phys Impact 7: 100278.

- Banerjee R, Kumar SPJ, Mehendale N, Sevda S, Garlapati VK (2019) Intervention of microfluids in biofuel and bioenergy sectors: Technological considerations and future prospects. Renew & Sustain Energy Reviews 101: 548-558.

- Al-Sakkari EG, Abdeldayem OM, El-Sheltawy ST, Abadir MF, Soliman A, et al. (2020) Esterification of high FFA content waste cooking oil through different techniques including the utilization of cement Kiln dust as a heterogeneous catalyst: A Comprehensive Study. Fuel 279(2020): 118519.

- Fereidooni L, Tahvildari K, Mehrpooya M (2018) Trans-esterification of waste cooking oil with methanol by electrolysis process using KOH. Renewable Energy 116: 183-193.

- Nwakwuribe VC, Nwadinobi CP, Igri UO, Ochiabuto NC, Ibegbu NC (2024) Effects of transesterification process parameters on production of biodiesel from oil extracted from catfish using raw, acid, alkaline and thermal modified potassium hydroxide as catalyst. J Appl Sci Environ Manage 28(8): 2515- 2524.

- Peppas GO, Charalampakos VP, Pyridi EC, Danikas MG, Bakandritos A, et al. (2016) Statistical investigation of AC breakdown voltage of nanofluids compared with mineral and natural ester oil. IET Journal 10(6): 644-652.

- Gen Z, Yao T, Zhang M, Hu J, Liao X, et al. (2020) Effect of temperature on the composition of a synthetic hydrocarbon aviation lubricating oil. Materials 13(7): 1606.

- Ortiz A, Delgado F, Ortiz F, Fernandez I, Santisteban A (2018) The ageing impact on the cooling capacity of natural ester used in power transformers. Appl Therm Eng 144(5): 797-803.

- Kittikhuntharado Y, Pattanadech N, Maneerot S, Jongvilaikasem K, Jariyanurat K, et al. (2023) Physical and chemical properties comparison of natural ester and palm oil used in a distribution transformer. Energy Reports 9(1): 549-556.

- ISO 3104 (1994) Petroleum product-transparent and opaque liquids-determination of kinematic viscosity and calculation of dynamic viscosity.

- Egbuna SO, Ude OC, Ude CN (2016) Suitability of soyabean seed oil as transformer oil. Int J Eng Sc & Research Techn 5(10): 1-8.

- IEC 60814 (1985) Determination of water in insulating liquids by Automatic Coulometric Karl Fisher Titration.

- IEC 60247 (1978) Measurement of relative permittivity, dielectric dissipation factor and d.c. resistivity of insulating liquids.

- Mohammadi H, Moradpoor H, Beddu S, Mazaffari HR, Sharifi R, et al. (2025) Current trends and research advances on the application of TiO2 nanoparticles in dentistry: How far are we from clinical translation? Heliyon 11(3): e42169.

- Beg M, Kumar P, Choudhary P, Sharma S (2020) Effect of high temperature ageing on TiO2 nanoparticles enhanced drilling fluids: A rheological and filtration study. Upstream oil and Gas Technology 5: 100019.

- Jenima J, Dharshini MP, Ajin ML, Moses JJ, Retnam KP, et al. (2024) Comprehensive review of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in cementitious composites. Heliyon 10(20): e39238.

- Kurimsky J, Rajnak M, Paulovicova K, Sarpataky M (2024) Electrical partial discharges in biodegradable oil-based ferrofluids: A Study on Effects of Magnetic field and nanoparticles concentration. Heliyon 10(7): e29259.

- Somet M, Kallel A, Serghei A (2022) Maxell-Wagner-Sillars interfacial polarization in dielectric spectra of composite materials: Scaling laws and applications. Hal Open Sc 56(20): 3197-3217.

- Chen B, Yang J, Li H, Su Z, Chen R, Tang C (2023) Electrical properties enhancement of natural ester insulating oil by interfacial interaction between KH550-TiO2 and oil molecules. Surfaces and Interfaces 42 Part B: 103441.

- Paternina C, Quintero H, Mercado R (2023) Improving the interfacial performance and the absorption inhibition of an extended-surfactant mixture for enhanced oil recovery using different hydrophobicity nanoparticles. Fuel 350: 128760.

- Gupta J, Agarwai M, Dalai AK (2020) An overview on the recent advancement of sustainable heterogeneous catalysts and prominent continuous reactors for biodiesel production. J Indust Eng Chem 88: 58-77.

- Baruah N, Maharana M, Nayak SK (2019) Performance analysis of vegetable oil-based nano-fluids used in transformers. IET Sc Measur & Techn 13(71): 995-1002.

- Rafiq M, Shafique M, Azam A, Ateeq M, Khan IA, et al. (2020) Sustainable, renewable & environmental-friendly insulation systems for high voltage applications. Molecules 25(17): 3901.

- Marino F, Lineira, de Rio JM, Lopez ER, Fernandez J (2023) Chemically modified nanomaterials as lubricant additive: time stability, friction, and wear. J Mole Liquids 382: 121913.

- Liu Z, Wang X, Gao H, Yan Y (2022) Experimental study of viscosity and thermal conductivity of water based Fe3O4 nanofluid with highly disaggregated particles. Case Stud Therm Eng 35: 102160.

- Ajeena AM, Vig P, Farkas JA (2022) Comprehensive analysis of nanofluids and their practical applications for flat plate solar collectors: fundamentals, thermophysical properties, stability, and difficulties. Energy Reports 8: 4461-4490.

- (1995) IEEE guide for diagnostic field testing of electric power apparatus- part I: Oil filled power transformers, regulators, and reactors. IEEE Power Engineering Society.

- Hairom NHH, Soon CF, Radin Mohamed RMS, Morsin M, Zainal N, et al. (2021) A review of nanotechnological applications to detect and control surface water pollution. Environ Techn & Inno 24: 102032.

- Naseem T, Durrani T (2021) The role of some important metal oxide nanoparticles for wastewater and antibacterial applications: A review. Environ Chem & Ecotox 3: 59-75.

- Subramanie PAP, Padhi A, Ridzuan N, Adam F (2019) Experimental study on the effect of wax inhibitor and nanoparticles on rheology of Malaysian crude oil. JKSU-Eng Sc 32(8): 479-483.

© 2025 © Jonathan T Ikyumbur. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)