- Submissions

Full Text

Researches in Arthritis & Bone Study

Complex Patellar Tendon Repair: A Case Report of Traumatic Patellar Tendon Rupture After Total Knee Arthroplasty with Use of Patellofemoral Unloader Brace

Jonathan Willard1*, Edward Austin1,4,5,6, Matthew Powers1,4, Morgan Farrell1,4, Joseph Laurent1, Graylin Jacobs1 and Deryk Jones1,2,3

1Ochsner Andrews Sports Medicine Institute, Jefferson, USA

2Ochsner Therapy and Wellness, Jefferson, USA

3South College Doctorate of Physical Therapy Program, Knoxville and Nashville, USA

4Michigan Technological University of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Houghton, USA

5The University of Queensland School of Medicine, Ochsner Clinical School, New Orleans, USA

6Sutter Health Orthopedics and Sports Medicine Service Line, Emeryville, USA

*Corresponding author:Jonathan Willard, Ochsner Andrews Sports Medicine Institute, Jefferson, Los Angles, USA

Submission: December 12, 2025;Published: January 26, 2026

Volume2 Issue3January 26, 2026

Abstract

Introduction: Patellar tendon rupture following Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) is a rare but devastating

complication that compromises the extensor mechanism and poses substantial challenges for both

surgical reconstruction and postoperative rehabilitation. Optimal postoperative management remains

controversial, particularly in balancing graft protection with early functional recovery.

Case summary: We report the case of a 57-year-old male with obesity who sustained a traumatic patellar

tendon rupture six weeks after primary TKA. Surgical management consisted of a complex repair using

V-Y quadricepsplasty, suture and suture-anchor fixation, and augmentation with posterior tibial tendon

allograft and BioBrace®. Postoperatively, the patient deviated from the standard immobilization protocol

and transitioned early to a customized dynamic patellofemoral extension-assist brace. Despite early

full weight bearing and return to work against medical advice, the patient demonstrated progressive

improvements in range of motion, functional performance and patient-reported outcome measures

without repair failure or rerupture.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates that, in select patients, a customized dynamic extension-assist

brace may facilitate functional recovery after complex patellar tendon repair following TKA without

compromising repair integrity. Dynamic bracing may provide a viable adjunct to traditional postoperative

protocols by permitting controlled loading, improving gait confidence and supporting earlier return to

activities of daily living and work. Further study is warranted to define patient selection criteria and

optimal rehabilitation strategies.

Keywords:Patellar tendon rupture; Total knee arthroplasty; Extensor mechanism reconstruction; V-Y quadricepsplasty; Patellofemoral unloader brace; BioBrace®

Introduction

Ruptures of the patellar and quadriceps tendons can be debilitating injuries with longterm implications. Patellar tendon ruptures are rare injuries with a reported incidence of 0.68 per 100,000 people each year [1]. Patellar tendon rupture after Total Knee Arthroplasty or Total Knee Replacement (TKA or TKR) can pose even more significant long-term issues and has a reported incidence rate of 0.17% in the literature [2]. Patellar and quadriceps tendon (often termed extensor mechanism) injuries present with an inability to actively extend the knee and an associated patella alta. Surgical options include primary repair with suture and transosseuous tunnels versus suture anchors [3,4]. Extensor mechanism rupture requiring re-operation following TKA presents a difficult problem for the treating surgeon. This may require additional fixation and graft augmentation for a satisfactory result. Postoperative management is critical because extensor mechanism injury after total knee replacement typically occurs in middle-aged men with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, chronic renal failure, and hypercholesterolemia [5]. In a traditional patellar tendon rupture without TKA, it is generally thought that the repair must be protected to prevent suture failure and elongation of collagen tendon fibers. Poor outcomes are typically associated with extension lag of ≥ 30° (inability of the individual to actively extend their knee fully), re-rupture, inability to return to pre-surgical ambulatory status and/or requirement for revision surgery [6- 8]. Theoretically, a lack of stiffness and elasticity in the tendon results in poor transmission of force from the quadriceps to the tibia. Literature has revealed that over 50% of those who undergo quadriceps tendon repair experience a long-term unresolved strength deficit > 20% compared to the contralateral limb [9]. Therefore, postoperative tension and strain on the graft must be monitored and controlled. Previous research has revealed surgical repair performed at full extension is effective with various allograft techniques in prevention of extension lag [7,10-12]. However, there is conflicting literature on the best practice of protecting the patellar tendon repair in postoperative rehabilitative care. Less evidence exists for protection of the repairs performed with graft augmentation in the setting of prior TKA.

Full weight bearing is encouraged immediately after TKA. Weight bearing as tolerated after extensor mechanism repair is encouraged immediately as well in most protocols but requires the use of a hinged knee brace. Variations exist in protocols, but typically the knee brace is locked at full extension during the first six weeks. Some protocols allow ROM of 0-60° at 4 weeks and full ROM unlocking the knee brace at 6 weeks [22]. Others require the knee brace fully locked in extension during weight bearing for 6-8 weeks [21]. The goal in the initial 12 weeks postoperatively is to control the forces imparted on the quadriceps tendon repair. However, previous research has shown the importance of muscle contraction as a stimulus for growth of collagenous tissue within the repair [17,21,25]. After total knee replacement, in absence of extensor mechanism injury, patients are encouraged to walk weight bearing as tolerated with proper assistive equipment (rolling walker versus crutches) immediately on the day of surgery. The patient may use a straight leg brace (no hinge or locked immobilizer) for the initial 48- 72 hours postoperatively for pain relief. However, immobilization is not recommended and is usually discouraged after 48-72 hours [23,24]. Clearly, there is a significant disparity in postoperative care between knee replacement and extensor mechanism repair protocols. In these circumstances, the more conservative protocol (extensor mechanism repair) must be followed. However, it is still particularly important to consider the strength of the quadriceps muscle with weight bearing for prevention of falls when walking, descending steps and activities of daily living such as getting in/out of the bathtub, on and off the commode, etc.

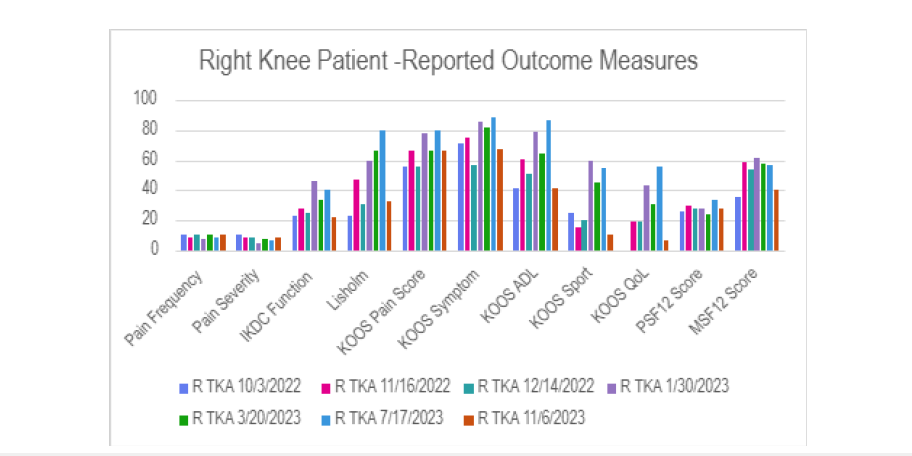

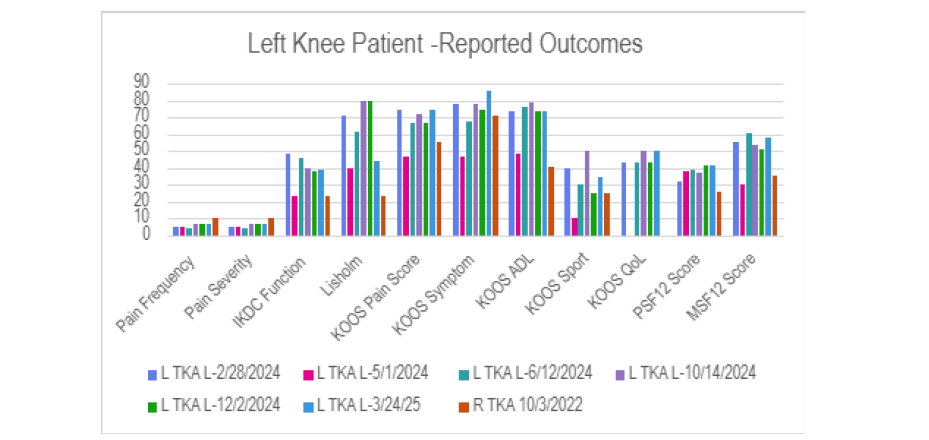

Besides the components of healing, ROM and strength, a patient’s return to function and daily life must be considered. Unfortunately, adults undergoing total knee replacement and extensor mechanism repair must consider the need for assistance to complete activities of daily living, inability to return to driving (especially if the right lower extremity is affected), and time off work for recovery. One study revealed that 98% of those who worked before undergoing TKA returned to work at an average of 8.9 weeks postoperatively [26]. According to studies of extensor mechanism repair, approximately 96% of those undergoing repair were able to return to work [27]. However, existing studies predominantly focus on return to sport or full activity rather than occupational reintegration, leaving the timing of return to work largely unreported. A lack of literature also exists for return to work and average time of return to work for those that have undergone TKA and concomitant extensor mechanism repair. Subjective questionnaires including the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Lysholm and Short Form 12 (SF-12) have been utilized to better understand functional limitations and pain following extensor mechanism repair in the patient with a prior TKA. These questionnaires, referred to as Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs), use the concept of Minimally Clinically Important Difference (MCID) to determine whether a patient perceives a surgery or intervention as beneficial in comparison to the expense, side effects and time required for rehabilitation [28,29]. The IKDC is a 10-item questionnaire with a high score of 100 points (highest function without problems) to 0 points (lowest function and pain). There are a variety of questions in relation to daily functional activities to sport related activities [30].

The KOOS is a robust 42-item questionnaire that involves five

separate tests:

i. Pain,

ii. ADL Function,

iii. Sport and Recreation Function,

iv. Quality of Life, and

v. Symptom. Similar to the IKDC, each of the KOOS subscales

has a range of scoring from 0-100 with 0 representing significant

knee pain and functional deficits and 100 representing highest

function and lowest pain [31].

The Lysholm knee scoring scale is an 8-question questionnaire with categories of limp, type of support/assistive device, locking of the knee, instability, pain, swelling, stair-climbing, and squatting. Scores of 95-100 indicate an excellent outcome, 84 to 94, a good result, 65 to 83, a fair result, and < 65 indicates a poor result [32]. Finally, the SF-12 is a 12-question questionnaire utilized with the intention to measure the general health-related quality of life. It has been used for a variety of conditions as diverse as psoriasis [33] and lung cancer [34]. Scores range from 0-100 with 100 representing the highest physical and mental functioning [34]. PROMs are displayed in Chart 1 & Chart 2. A thorough literature review revealed a void in research of MCID values related to extensor mechanism repair. MCID research was substantial in relation to the topics of ACL repair, articular cartilage techniques, hip and total knee arthroplasties. MCID values were found for the 3 through 24-month period following postoperative TKA for the KOOS subscales. MCID two years following TKA using KOOS subscales were 10-15.3 for pain, 6-15.3 for symptoms, 6-16.0 for ADL, 8-11.8for sport/recreation, and 10-14.4 for quality of life [35,36]. MCID values of 1.8 and 1.5 have been reported 1-year postoperatively for TKA with the PSF- 12 and MSF-12, respectively [37]. MCID values for the Lysholm and IKDC tests have not been established as these PROMs are used to evaluate a more athletic population.

Chart 1:R. Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs).Date of Surgery: 11/01/2022

Chart 2:L. Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs).Date of Surgery: 01/23/2024

Objective measurements are also utilized to track progress and stir patient engagement during the postoperative period. Functional assessments such as the five-times sit-to-stand and 6-meter walk tests are often utilized after total knee arthroplasty. The five-times sit-to-stand test is a timed test in which the patient moves from a sitting to a standing position five times. There are time-related norms that the postoperative patient is encouraged to reach throughout the rehabilitation period. Age-related normative values for community dwelling individuals in decade increments (40-49, 50-59, etc.) have been recorded [38] as well as a 12.5-second cutoff time for increased risk of fall [39]. Normative ranges (67.1 ± 27.8 kilograms) for quadriceps isometric strength have also been recorded for individuals between 50-85 years [38]. This data provides solid criteria for health care practitioners as well as those recovering from a postoperative knee procedure. In this case study, the operative and postoperative care of an individual that underwent TKA is reviewed. Unfortunately, this individual suffered an extensor mechanism injury six weeks after knee arthroplasty and required surgical repair. This patient followed an unconventional path and returned to work earlier than typically recommended by health care providers. The patient utilized a novel extension-assist ICARUS® Ascender brace (Icarus Co., Charlottesville, VA) rather than the traditional hinged knee immobilizer at 2 weeks following repair to assist in the early return to work.

History and Physical Exam

A 57-year-old male with obesity (Body-Mass Index [BMI], >35), varus lower extremity alignment, and bilateral knee arthroplasty history presented following a traumatic injury to the left knee. The patient was initially referred for a painful medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in the setting of varus deformity and elevated BMI, which was felt to be the primary etiology of failure. He subsequently underwent a right revision Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) performed by the senior author. During recovery from the right revision TKA, the patient developed progressive left knee pain with patellofemoral and medial compartment degenerative disease, which was managed conservatively with injection therapies and use of an ICARUS® Ascender (ICARUS Inc., Charlottesville, VA) patellofemoral unloader brace by the senior author. After complete functional recovery of the right knee, the patient proceeded with a primary left TKA. At 5 weeks postoperatively, Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and radiographs demonstrated satisfactory early recovery. However, one week later, the patient sustained a ground-level fall with hyperflexion of the left knee, resulting in acute pain and inability to actively extend the knee. Imaging demonstrated patella alta compared with prior postoperative films and based on the mechanism of injury and physical examination the patient was diagnosed with a patellar tendon rupture.

The patient underwent operative repair as described and was placed postoperatively in a standard T-scope brace locked in full extension. Due to his elevated BMI and conical lower extremity morphology, the brace repeatedly migrated distally and failed to maintain proper positioning. Without consulting the treating surgeon, the patient discontinued use of the T-scope brace and resumed use of his previously fitted ICARUS® Ascender patellofemoral unloader brace. At his 2-week postoperative follow-up, he reported minimal pain and demonstrated good early functional recovery. By 6 weeks post-repair, he was able to perform an active straight leg raise and active full knee extension from a seated position at 90 degrees of flexion with no lag noted. This demonstrates with appropriate surgical technique the ICARUS® Ascender provides benefits over standard hinged knee immobilizers in a complex condition. The customized nature of the brace created from the 3-dimensional image created by the software in the ICARUS® application appropriately protected the repair expediting patient mobility post-operatively. The early excellent functional returns demonstrated at 6 weeks post-operatively highlight these benefits.

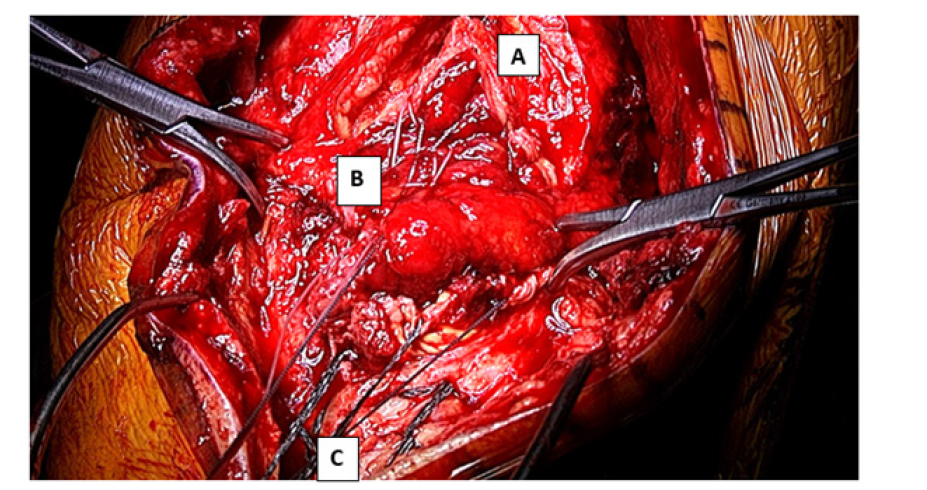

Operative Technique

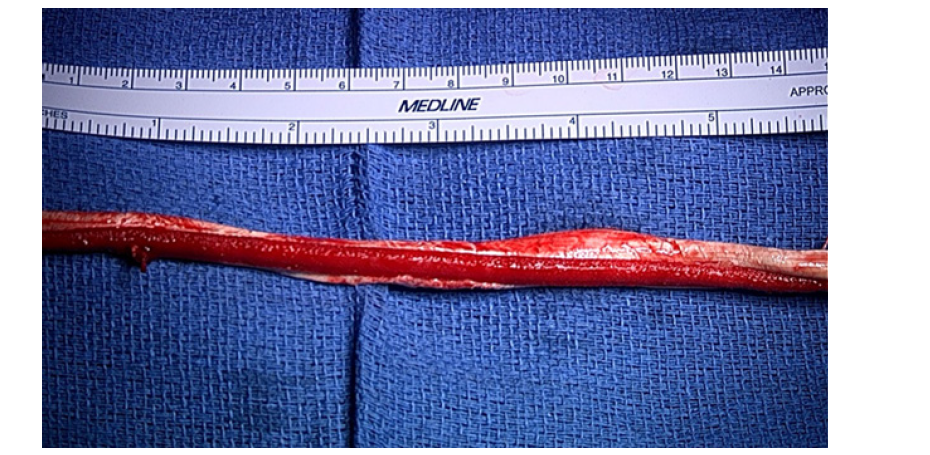

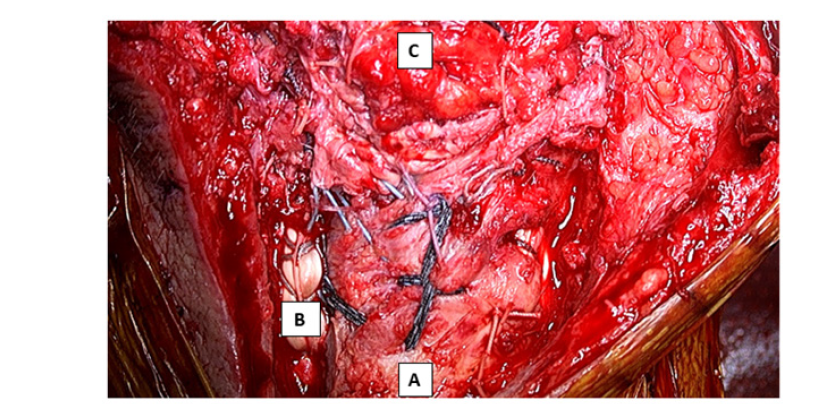

The patient was placed in prone position, and the previous medial-based knee incision was used exposing the quadriceps and patellar tendons. There was a complete tear of the patellar tendon with resultant patella alta. A V-Y quadricepsplasty was performed allowing 2cm lengthening reducing load to the patellar tendon repair. (Figure 1) The medial and lateral aspects of the mobilized patellar tendon were sewn with Krackow technique leaving 4 exiting suture limbs distally. A suture anchor was placed in the inferior pole of the patella to augment fixation of the distal aspect of the patella. The distal portion of the patellar tendon tear was then sewn Krackow fashion as well with the suture limbs exiting the proximal portion of the patellar tendon tear. Sutures from the anchor were sewn into the distal portion of the patellar tendon using the modified Kessler technique and tensioned; this re-approximated the distal portion of the patellar tendon to the inferior border of the patella. The proximal and distal suture limbs from the Krackow sutures were tied into the opposite side of the tear in modified Kessler fashion as well and tied. To augment repair, a posterior tibial tendon freshfrozen allograft (MTF Biologics, Inc., Edison, NJ) was sewn in whipstitch fashion proximally and distally was then combined with a 0.5 x 250 mm BioBrace augmentation graft (CONMED Inc., Naples, FL.). The two grafts were sewn together in a tubular fashion using #1 Vicryl sutures. The combined graft was passed through the medial, proximal and then lateral portions of the patella repair and secured to the proximal tibia with knotless 5.5mm anchors placed first medially and then laterally along the proximal tibia with the knee at 30° flexion to further augment and protect the patellar tendon tear. (Figure 2) The medial and lateral retinacular structures were closed as well with a series of interrupted #1 Vicryl sutures. The paratenon had been preserved during exposure of the tear and was closed over the patellar tendon tear. The skin and subcutaneous tissues were closed in typical layered fashion.

Figure 1:Intra-operative photograph showing V-Y quadricepslasty and reapproximation of torn patellar tendon.

A = Quadriceps tendon,

B = Patella,

C = Patellar tendon.

Figure 2:Prepared posterior tibial tendon allograft with BioBrace® augmentation prior to placement.

Postoperatively, the patient was instructed to keep the knee locked in extension with a T-scope brace (BREG, Inc., San Diego, CA.) and maintain a Toe-Touch Weight-Bearing (TTWB) to 25% Partial Weight-Bearing (PWB) status. As stated previously, the patient had undergone a prior right revision TKA. During the rehabilitation process following this procedure, the patient was fitted with an ICARUS® ascender brace for the left knee due to increasing patellofemoral symptoms. As a result, he was aware of the extension-assist benefits but also was aware of the customized fit of the brace. He had used this brace to unload the patellofemoral compartment of his left knee prior to reconstruction. He was also aware of the functional extension assistance provided by the dynamic nature of the brace. As a result, he had this brace available post-operatively following left TKA but was not using it. When he tore the patellar tendon 6 weeks post-operatively, he was comfortable switching to the brace 2 weeks following repair of the patellar tendon tear. Due to his high BMI and the conical nature of his thigh, the patient had difficulty maintaining the T-scope brace in the correct position following patellar tendon repair and discontinued use of the T-scope® at approximately 2 weeks and began using the ICARUS® Ascender instead. The patient presented to clinic walking in the dynamic brace with no assistive device at his 2-week postoperative appointment, which was unexpected. The brace fit well due to the customized design, which was based on three-dimensional scanning used through the application to capture the patient’s true anatomy and produce a precise, comfortable fit. This enabled the patient to walk with a form-fit brace shortly after a complex patellar tendon repair with a BMI of 37.3. The brace can be locked out in full extension with gait if fully tensioned preventing passive or active flexion. It can be released while sitting to allow for flexion preventing difficulties with activity of daily living. Further, the tension on the Ascender brace can be modulated to provide full assistance with extension or varying degrees of tension to provide partial assistance. As a result, as the patient improves muscle control and strength the tension can be lessened with time. The standard postoperative rehabilitation protocol is listed in Table 1. The patient did not follow this protocol and began full weightbearing after one week using the ICARUS® Ascender brace rather than the traditional T-scope® and crutch assistance with TTWB to 25% PWB. Postoperative rehabilitation metrics and objective measurements are summarized in Table 2. Clinical photographs demonstrating functional recovery and bracing are seen in Figure 4-6.

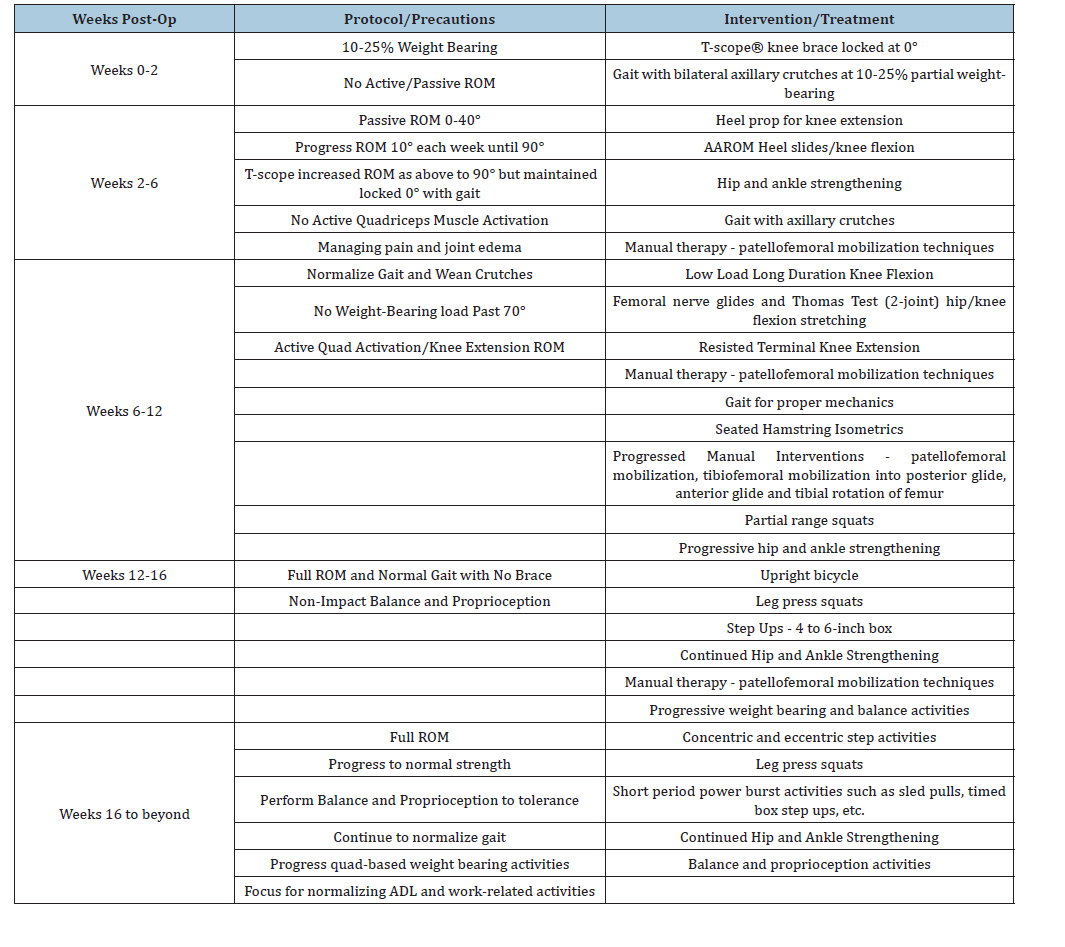

Table 1:V-Y quadricepsplasty protocol and exercise during the various postoperative time periods.

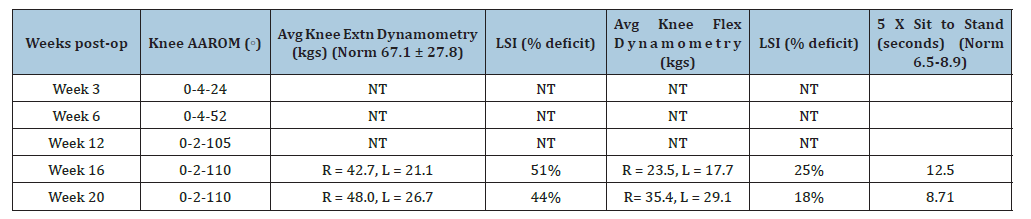

Table 2:Postoperative rehabilitation metrics; Postoperative objective measurements.

Figure 3:Patellar tendon repair using suture and suture anchor technique with posterior tibial tendon (PTT) allograft and BioBrace® augmentation. A = Patellar Tendon, B = PTT Allograft and BioBrace®, C = Patella inferior pole

Figure 4:Seated active knee extension performed in clinic, illustrating restoration of the extensor mechanism at 6 weeks post-operatively.

Figure 5:Supine position demonstrating the 3-dimensional, patient-specific ICARUS® Ascender brace with a customized fit; the top side dial allows variable tensioning of the patellofemoral unloading mechanism present in the hinges at the knee level.

Figure 6:Weight-bearing (WB) stance in the ICARUS® Ascender brace, highlighting maintained alignment and functional stability during standing. This was fully tensioned to prevent active or passive flexion at this point in the recovery. Full WB was allowed with no assistance.

Discussion

This case study highlights an individual who underwent TKA and sustained a traumatic rupture of the patellar tendon six weeks postoperatively. The complex surgical repair of the patellar tendon consisted of V-Y quadricepsplasty, suture and suture anchor fixation with Posterior Tibial Tendon (PTT) allograft/BioBrace® augmentation. Postoperative care followed a protocol designed to restrict premature range of motion to minimize the risk of tendon strain or elongation, while allowing hip flexor use and dynamic assist loading of the patellofemoral joint. Immediately postoperatively, the individual wore a T-scope knee brace with the knee locked in 0° knee extension. He was initially told to perform TTWB to 25% PWB with use of crutches for assistance. As stated previously, this patient with a BMI of 37.3 had difficulty maintaining the T-scope® in the correct position. Without medical recommendation, the patient made an appropriate decision, recognizing the difficulties using the traditional hinged knee immobilizer. These types of immobilizers tend to drift distally, have no dynamic component preventing subtle adjustments to the level of immobilization or extension assistance. Further, the ICARUS® Ascender brace was customized to the patient’s knee allowing for a more direct fit to the patient’s soft tissue anatomy. The brace can be tensioned to full extension and is strong enough to resist any passive or active flexion. Further, the lateral dial has a central button that can be pushed once the patient is in a sitting position at rest allowing flexion as tolerated. By placing the customized dynamic unloader, greater extensor mechanism and hip flexors muscle activation was elicited while providing better protection of the patellar tendon repair site. By allowing easy flexion at rest the patient can avoid migration of the brace as well.

Considering the complex repair in the setting of a patient with obesity and recent ipsilateral TKA, the goal was to cautiously wean this patient from hinged immobilizer into the dynamic customized brace over six weeks. At the two weeks postoperative visit, the patient had completely stopped using the T-scope® brace and was utilizing the ICARUS® brace exclusively. This raised concern among the rehabilitation staff as the patient had also returned to work in a position where prolonged walking, ascending and descending ladders and consistent movement was required. In retrospect, this was a positive development for the reasons described above. Despite the concern of the rehabilitation staff, the patient did not experience repair failure or any significant complications. Objective measurements were utilized to monitor the patient’s progress and promote engagement. ROM values progressed appropriately, although the patient did not reach 120° of knee flexion at final follow-up. Isometric knee extension and flexion strength values were captured with dynamometry at weeks 12,16 and 20. Surgical side limb symmetry index for knee extension strength revealed significant knee weakness on the left (operative) side compared to the right (non-operative) side.

Compared to the normative range with one standard deviation (67.1 ± 27.8), the right (non-operative) leg would be considered normal within one standard deviation. However, the left (operative) leg had not yet achieved normal range. Despite that weakness, this individual achieved an age-related normal test time for the functional five-times sit-to-stand test. At 16 weeks post-op, this individual became inconsistent with physical therapy. However, he did report the ability to perform job duties and normal daily activities without distress [37]. At week 12, pain severity and frequency scores decreased. Interestingly, those scores increased at weeks 30 and 37. The increase in pain severity and frequency could be a result of increased daily life activities. At weeks 12 and 30, improvements were noted in IKDC, Lysholm, KOOS subscales and MSF-12 scores. According to the established 3 and 6-month MCID values for total knee replacement mentioned above, MCID was met for all KOOS scores compared to 6 weeks postoperative quadriceps repair. There were a plateau and slight regression noted between the 30-week and 37-week scores on all assessments.

Conclusion

Overall, this case demonstrates a successful functional recovery following a complex set of surgeries. This also details how technological advancements in brace wear, such as a knee extensionassist device, can aid in gait and functional activities when a knee extension strength deficit is suspected. A typical scenario seen by the senior author in the past is poor compliance with standard immobilization leading to the development of an extension lag in many cases. Between weeks 6-12 postoperatively, significant functional improvements occurred despite significant changes from the traditional bracing and rehabilitation protocol; despite this variation the repair remained intact and increased activities continued. The patient returned to full work duties during that time which was at an early stage following repair. During weeks 12-30, the patient continued to functionally progress according to PROMs and demonstrated improvements in quadriceps and hamstring strength as well as five-times sit-to-stand testing. The weakness at the left quadriceps compared to the right was evident at the latest evaluation in therapy but improving. This emphasizes the role of an extension-assist brace in building patient confidence during loading and functional use of a surgically repaired lower extremity. We have seen continued improvement in the patients function with time.

Financial Support and Disclosures

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient Consent/Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained for experimentation with human subjects.

References

- Fredericks DR, Sean ES, Conor FC, Marvin ED, Theodore JS, et al. (2021) Incidence and risk factors of acute patellar tendon rupture, repair failure, and return to activity in the active-duty military Population. Am J Sports Med 49(11): 2916-2923.

- Rand JA, Morrey BF, Bryan RS (1989) Patellar tendon rupture after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 244: 233-238.

- Bushnell BD, Tennant JN, Rubright JH, Creighton RA (2008) Repair of patellar tendon rupture using suture anchors. J Knee Surg 21(2): 122-129.

- Tarazi N, Loughlin PO, Amin A, Keogh P (2016) A rare case of bilateral patellar tendon ruptures: A case report and literature review. Case Rep Orthop 2016: 6912968.

- Jacob DP, Bitar YE, Mabrouk A, Plexousakis MP (2025) StatPearls Publishing.

- Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN (1989) Rationale of the knee society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 248: 13-14.

- Brown NM, Della Valle CJ, Sporer SM, Wetters N, Berger RA, et al. (2015) Extensor mechanism allograft reconstruction for extensor mechanism failure following total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 97(4): 279-283.

- Balato G, Franco C, Lenzi M, Baldini A, Robert SJB, et al. (2023) Extensor mechanism reconstruction with allograft following total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis of achilles tendon versus extensor mechanism allografts for isolated chronic patellar tendon ruptures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 143(7): 4411-4424.

- Konrath GA, Chen D, Lock T, Goitz HT, Watson JT, et al. (1998) Outcomes following repair of quadriceps tendon ruptures. J Orthop Trauma 12(4): 273-279.

- Rosenberg AG (2012) Management of extensor mechanism rupture after TKA. J Bone Joint Surg Br 94(11 Suppl A): 116-119.

- Gencarelli P, Jonathan PY, Alex T, Salandra J, Luke GM, et al. (2023) Extensor mechanism reconstruction after total knee arthroplasty with allograft versus synthetic mesh: A multicenter retrospective cohort. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 31(1): e23-e34.

- Bonnin M, Lustig S, Huten D (2016) Extensor tendon ruptures after total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 102(1 Suppl): S21-S31.

- West JL, Keene JS, Kaplan LD (2008) Early motion after quadriceps and patellar tendon repairs: Outcomes with single-suture augmentation. Am J Sports Med 36(2): 316-323.

- Woo SL, Matthews JV, Akeson WH, Amiel D, Convery FR (1975) Connective tissue response to immobility. Correlative study of biomechanical and biochemical measurements of normal and immobilized rabbit knees. Arthritis Rheum 18(3): 257-264.

- Jortikka MO, Inkinen RI, Haapala J, Kiviranta I, Helminen HJ, et al. (1997) Immobilisation causes long-lasting matrix changes both in the immobilised and contralateral joint cartilage. Ann Rheum Dis 56(4): 255-261.

- Nagai M, Akira I, Junichi T, Shoki Y, Tomoki A, et al. (2016) Remobilization causes site-specific cyst formation in immobilization-induced knee cartilage degeneration in an immobilized rat model. J Anat 228(6): 929-939.

- Kjaer (2004) Role of extracellular matrix in adaptation of tendon and skeletal muscle to mechanical loading. Physiol Rev 84(2): 649-698.

- Carlson SCR, Laprade MD, Keyt LK, Wilbur RR, Krych AJ, et al. (2021) A strategy for repair, augmentation and reconstruction of knee extensor mechanism disruption: A retrospective review. Orthop J Sports Med 9(10): 23259671211046625.

- Franco C, Matteo V, Ernesto M, Alessio B, Francesco S, et al. (2022) The active knee extension after extensor mechanism reconstruction using allograft is not influenced by early mobilization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 17(1): 153.

- Montalto M, Otto V (2025) Quadriceps tendon/patellar tendon repair clinical practice guideline. The Ohio State University.

- Garrett C, Davis MD, Kevin W Rehabilitation protocol for patella/quad tendon repairs, pp. 1-5.

- Quad / patellar tendon repair rehabilitation protocol. North Fork Orthopaedic and Sports Medicine, pp. 1-2.

- Ghazinouri R, Rubin A, Congdon W (2012) Total Knee Arthroplasty Protocol. Brigham and Women's Hospital, pp. 1-7.

- Schmitt LC, Tiemeier L, Walker J, Wayman K (2019) Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) POST-OP clinical practice guideline. The Ohio State University, USA, pp. 1-11.

- Wisdom KM, Delp SL, Kuhl E (2015) Use it or lose it: Multiscale skeletal muscle adaptation to mechanical stimuli. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 14(2): 195-215.

- Lombardi AV, Ryan MN, John CC, William GH, Robert LB, et al. (2014) Do patients return to work after total knee arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(1): 138-146.

- Haskel JD, Edward SM, Michael JA, Kirk AC, Fried WJ, et al. (2021) High rates of return to play and work follow knee extensor tendon ruptures but low rate of return to pre-injury level of play. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 29(8): 2695-2700.

- Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH (1989) Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials 10(4): 407-415.

- Goldberg B, David G, Zachary KC, Mark JS, Henry DC, et al. (2023) Changes over a decade in patient-reported outcome measures and minimal clinically important difference reporting in total joint arthroplasty. Arthroplast Today 20: 101096.

- Collins NJ, Misra D, Felson DT, Crossley KM, Roos EM (2011) Measures of knee function: International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee evaluation form, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score Physical Function Short Form (KOOS-PS), Knee Outcome Survey Activities of Daily Living Scale (KOS-ADL), lysholm knee scoring scale, Oxford Knee Score (OKS), Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), Activity Rating Scale (ARS), and Tegner Activity Score (TAS). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 63(Suppl 11(Supply 11)): S208-28.

- Roos EM, Toksvig LS (2003) Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) - validation and comparison to the WOMAC in total knee replacement. Health Qual Life Outcomes 1: 17.

- Kocher MS, Steadman JR, Briggs KK, Sterett WI, Hawkins RJ (2004) Reliability, validity and responsiveness of the lysholm knee scale for various chondral disorders of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86(6): 1139-1145.

- Sampogna F (2019) Use of the SF-12 questionnaire to assess physical and mental health status in patients with psoriasis. J Dermatol 46(12): 1153-1159.

- Soh SE, Renata M, Darshini A, Susannah A, Scarborough R, et al. (2021) Measurement properties of the 12-item short form health survey version 2 in Australians with lung cancer: A Rasch analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 19(1): 157.

- Watabe T, Sengoku T, Kubota M, Sakurai G, Yoshida S, et al. (2025) Knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score and knee society score for the minimal clinically important differences after cruciate-retaining total knee arthroplasty: Two-year follow up. Knee 53: 176-182.

- Nishimoto J, Tanaka S, Inoue Y, Tanaka R (2023) Minimal clinically important differences in short-term postoperative Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Orthopaedics, Trauma and Rehabilitation 31(1): 15-20.

- Clement ND, Weir D, Holland J, Gerrand C, Deehan DJ (2019) Meaningful changes in the short form 12 physical and mental summary scores after total knee arthroplasty. Knee 26(4): 861-868.

- Bohannon RW, Bubela DJ, Magasi SR, Wang YC, Gershon RC (2010) Sit-to-stand test: Performance and determinants across the age-span. Isokinet Exerc Sci 18(4): 235-240.

- Tiedemann A, Shimada H, Sherrington C, Murray S, Lord S (2008) The comparative ability of eight functional mobility tests for predicting falls in community-dwelling older people. Age Ageing 37(4): 430-435.

© 2026 Jonathan Willard. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)