- Submissions

Full Text

Researches in Arthritis & Bone Study

Evaluating Viscosupplementation Efficacy in Obese Knee Osteoarthritis Patients Using Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Deryk Jones1,2,3*, Jonathan Willard1, Eden Schoofs1, Graylin Jacobs1, David Otohinoyi1 and Savit Dhawan2

1Ochsner Andrews Sports Medicine Institute, Jefferson, LA, USA

2The University of Queensland School of Medicine, Ochsner Clinical School, New Orleans, LA, USA

3Sutter Health Orthopedic and Sports Medicine Service Line, CA, USA

*Corresponding author:Deryk Jones, Ochsner Andrews Sports Medicine Institute, Jefferson, LA, USA

Submission: October 09, 2025;Published: November 17, 2025

Volume2 Issue2November 17, 2025

Abstract

Background

Viscosupplementation refers to the use of hyaluronic acid injections into diarthrodial joints, typically the knee, to provide lubrication and shock absorption. It is commonly used for the treatment of knee Osteoarthritis (OA). One product, Synvisc® (Sanofi, Inc., Bridgewater, NJ), has been used in our clinic for over 20 years. Given the increasing prevalence of obesity and its known negative impact on OA outcomes, this study aimed to evaluate the influence of Body Mass Index (BMI) on patient outcomes following Synvisc® injection.

Methods

A single-center retrospective medical record review was conducted on 46 patients who received Synvisc® injections for symptomatic knee OA. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) included the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Knee Evaluation Form, Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, 12-Item Short Form Survey (SF-12), and the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS), recorded before and after injection. Patients were categorized as non-obese or obese using NIH BMI guidelines. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Significant improvements in PROMs were observed from baseline following Synvisc® injections in most patients. These improvements were more pronounced in non-obese patients (p<0.05). Obese patients showed greater activity and functional limitations, indicating a BMI-related effect on treatment response.

Conclusion

Synvisc® injections improved patient-reported- outcomes/quality of life and pain relief across all patient cohorts. However, pre-obese patients experienced more substantial improvements in pain sensation and quality of life metrics compared to their obese counterparts.

Keywords:Viscosupplementation; Osteoarthritis; Hyaluronic acid; Body mass index; Patient reported outcome measures

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) greatly impacts quality of life of the adult population worldwide, and the increasing prevalence has led to greater research efforts to investigate the cause and development [1]. It has been well documented that a known modifiable risk factor for both incidence and progression of OA is obesity [2,3]. The prevalence of obesity is rising, and severe obesity is expected to double from 10% to 20% from 2020 to 2035 [4,5]. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers the increase in prevalence of obesity a global epidemic as it affects hundreds of millions of individuals [6]. With the rising prevalence and association of obesity and OA, there is a need to advance our knowledge of OA and obesity to improve treatment and management of patients.

Osteoarthritis of the Knee (KOA) is one of the most common joints affected and there is a known association between obesity and knee osteoarthritis [7,8]. The development of new treatment modalities for KOA is of continued interest in the literature. Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA) surgically treats the symptoms of severe KOA. In the case of less severe KOA, various societies recommend conservative treatment modalities, such as exercise, oral and topical medications, and intra-articular injections with corticosteroids, platelet-rich plasma, or viscosupplementation [9].

Viscosupplementation treats symptoms of KOA through hyaluronic acid and its derivatives, restoring the natural viscoelasticity of the joint, thus minimizing friction between articular cartilage with movement [10]. This differs from other injections with anti-inflammatory properties. Studies analyzing hyaluronan and Hylan derivatives such as Synvisc-One® (Sanofi Inc., Bridgewater, NJ) suggest that viscosupplementation has similar efficacy to corticosteroids with fewer systemic adverse events and prolonged effects [11]. The adverse effects of viscosupplementation injections are usually minor. Pain, local swelling, and skin reactions are among the more common, while more serious side effects such as pseudoseptic reactions and infection are considered uncommon [12].

Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) and other tests are often used to evaluate outcomes of patients with KOA. The selection of appropriate PROMs is used to guide research and provide clinical context [13]. In this study, four different PROMs were collected to assess each knee of KOA patients treated with Synvisc-One® injections. The Lysholm Knee Scoring scale was initially developed to evaluate functional impairment of knees due to instability following meniscus ruptures [14]. The 12-item shortform health survey (SF-12) was developed as a shortened survey to better assess large-scale health measurements and monitoring effects [15]. The International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee form is a knee-specific PROM used to measure symptoms, function, and sports activity for patients with various knee problems [16]. And lastly, the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) was developed to evaluate short-term and long-term symptoms and function in individuals with KOA and knee injuries [17]. Therefore, this study is designed to investigate the response to Synvisc-One® injection using PROMS in patients stratified by their BMI.

Materials and methods

Study design and population

This was a retrospective study conducted at a single site from 2012 to 2024. Participants in the study were patients who have been diagnosed with Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) and have received at least one viscosupplementation injection in the affected knee. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD10) codes were used to verify KOA diagnosis. The total cohort was collected from a single physician’s repertoire of patients who agreed to participate in the study. Patients with knee injections prior to KOA diagnosis or less than 18 years of age were excluded from the study. Patients that received other types of therapeutic modalities for symptomatic KOA were also excluded from the study. Observations with at least one month of follow-up were used for the study.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional review board committee at Ochsner Clinic Foundation (IRB number: 2012.205). Each patient that participated in this study was provided with comprehensive informed consent. Patient data was handled to ensure confidentiality and privacy.

Viscosupplementation injection

For this study, the form of viscosupplementation used was Synvisc-One® only. All patients received one injection of 6 mL suspension of Synvisc-One®. Injections were administered by the same experienced physician with Ultrasound (US) guidance using a superolateral approach and 21-gauge needle. Ethyl chloride spray was applied prior to arthrocentesis, and all synovial fluid was aspirated using US verification prior to injection of Synvisc-One®. No regular analgesics or therapy were permitted during the study. When appropriate, NSAIDs were used for pain relief and reported to the study physician. No rescue medication was used 24 hours prior to follow-up clinic visit.

Data collection and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs)

Data collection was centered as joint-based per clinic visit and not patient-based, such that patients with KOA in both knees were assessed separately, and PROMs were collected for each knee per visit. Demographic data and clinical variables for each patient were collected from the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) system. To determine Body Mass Index (BMI) for each patient, patient weight and height at each clinic visit were collected to calculate BMI. In line with our study objectives, we recorded encounter date, BMI, and PROMs for each affected knee per visit to determine BMI and PROM correlation. To determine reference, PROMs collected prior to Synvisc-One® injection served as baseline for reference. Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was also used to capture pain frequency and pain severity on a 0-10 scale with lower number meaning less discomfort.

To capture the efficacy of Synvisc-One® in obese KOA patients, we used standardized and validated PROMs such as Lysholm Knee Scoring scale, which measures knee chondral damage and the impact of Synvisc-One® in minimizing KOA symptoms [14]. The 12- item short-form health survey (SF-12) was used to assess overall health in KOA patients [15]. The International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) function was used to measure knee function and activity limitation [16]. Finally, we used Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) with KOA specific measure to comprehensively determine the effect of Synvisc-One® on obese KOA patients [17]. Our approach to use multiple standardized PROMs was to ensure multidimensional assessment of Knee health and overall health after Synvisc-One® injections in KOA patients. We collated the various aspects assessed by these PROMs to investigate various domains such as knee joint symptoms and pain, knee joint function, and general health. This approach ensured a comprehensive assessment of patient outcomes.

BMI Classification

To investigate how BMI impacts the efficacy of Synvisc-One® using PROMs, we further categorized BMI collected for each patient based on the National Institute of Health (NIH) classification into Obese (BMI≥30) and none-obese (BMI<30) [18]. This option was necessary to ensure sufficient size in capturing the impact of BMI.

Power and statistical analysis

In line with the objectives for this study, clinic visits resulting in PROMs and BMI collection were defined as an independent observation. Power analysis using Cohen’s effect size assumption for multiple regression of 0.02, power at 80% and alpha at 0.05 was used to determine the observation datapoint were sufficient to investigate our study hypothesis [19].

To evaluate how obese and non-obese KOA patients respond to Synvisc-One® injections, we maintained the PROMs as the primary outcome and analyzed in relation to BMI classification, that is, obese versus non-obese. PROMs collected prior to Synvisc-One® injection, defined as baseline, were compared within and across observations to PROMs at follow-up clinic visits to determine improvement or deterioration. Descriptive analysis was done to explore the patient population used for the analysis. For each PROM stratified by BMI classification, scatterplots with linear regression were used to assess relationships. Pearson correlation was also used to quantify the strength and direction of these associations. Where applicable, linear modeling was used to determine if PROMs varied over time within obese and non-obese groups. An independent sample t-test was used to assess differences in PROMs between obese and nonobese groups. For all analysis, p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analysis in this study was done using R (version 4.2.2) in RStudio (version 2023.03.0 Build 386).

Result

Patient demographics

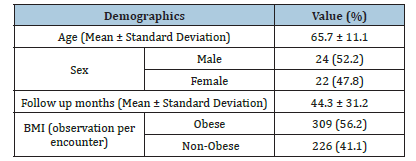

A total of 550 datapoint samples were collected from 46 patients. Descriptive analysis of the patients used for this study is shown in Table 1. Each observation encounter was matched with the corresponding PROMs and BMI value per encounter. BMI distribution for the study had a mean and standard deviation of 30.7±4.1. BMI values were used to create BMI classification of obese or non-obese for each observation. This served as the groundwork to investigate the impact of obesity on PROMS in KOA patients injected with Synvisc-One® (Table 1).

Table 1:Descriptive analysis of patients used in the study.

Trend in pain frequency and pain severity between obese and non-obese

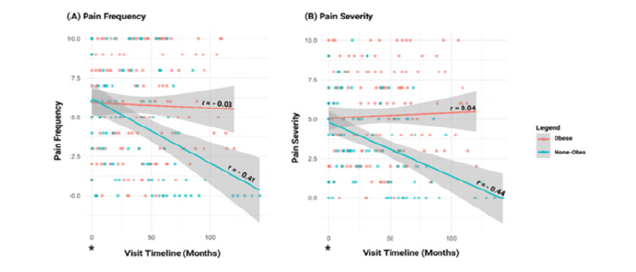

Figure 1:Linear model plots and correlation analysis of Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores for pain frequency (A) and pain severity (B) in patients with knee Osteoarthritis (OA) over time, stratified by obesity status. VAS scores range from 0 to 10, with lower values indicating less symptomatic knee OA. Baseline measurements (*) were used as reference points to assess longitudinal trends. Red indicates the obese group, and mint green indicates the non-obese group.

We considered data collected by VAS on a 0-10 scale at each encounter to determine the association between Synvisc-One® injection and BMI classification. Pain frequency and pain severity for obese and non-obese at each encounter post Synvisc-One® injection was used to determine the trend on the VAS scale over time (Figure 1A&1B). The linear curve showed a downward trend in pain frequency and severity in non-obese patients, which was less pronounced in the obese group (Figure 1A&1B). Linear model analysis showed that pain frequency and severity at baseline did not improve after Synvisc-One® injection in obese patients, p>0.05, however, improvement from baseline was observed in non-obese patients, p<0.001. When comparing obese to non-obese patients, there was a significant difference in pain frequency (p<0.001, 95% CI: 0.28 to 2.04), and pain severity (p<0.001, 95% CI: 0.98 to 2.4).

Impact of obesity on PROMs after synvisc-one® injection

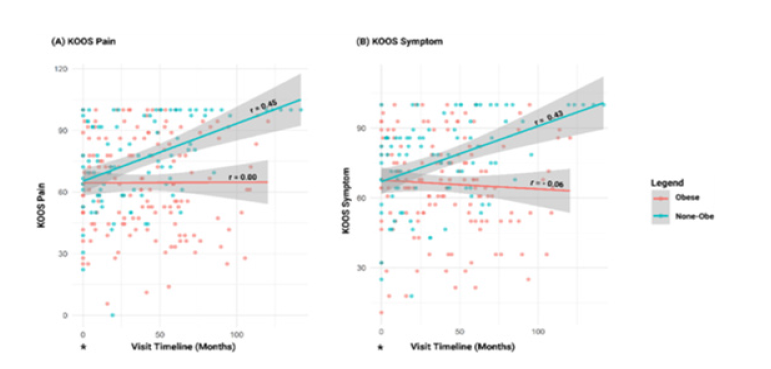

We used 4 standardized PROMs to ensure a comprehensive

psychometric assessment of KOA patients post Synvisc-One®

injection. The standardized PROMs were categorized into knee

joint symptoms and pain, knee joint function, and general health.

Knee joint symptoms and Pain: To determine if obesity affects

the effectiveness of Synvisc-One® on KOA patients regarding knee

joint symptoms such as swelling, stiffness, and pain, we collected

KOOS pain and KOOS symptoms between obese and non-obese

patients for analysis. Pearson correlation showed an improvement

in symptomatic knee OA in non-obese KOA patients over time post

injection (Figure 2A). A similar trend was observed with KOOS pain

PROMs (Figure 2B). Comparing obese to none-obese showed a

significant difference, p<0.05 (Table 2).

Figure 2:Linear model plots and correlation analysis of standardized PROMs for KOOS Pain (A) and KOOS symptom (B) in patients with knee Osteoarthritis (OA) over time, stratified by obesity status. A higher score for these PROMs indicates less symptomatic knee OA as reported by the patient. Baseline measurements (*) were used as reference points to assess longitudinal trends. KOOS=Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score. Red indicates the obese group, and mint green indicates the non-obese group.

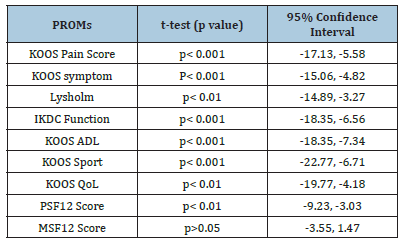

Table 2:Comparison of PROMs between Obese and None-Obese patients with KOA.

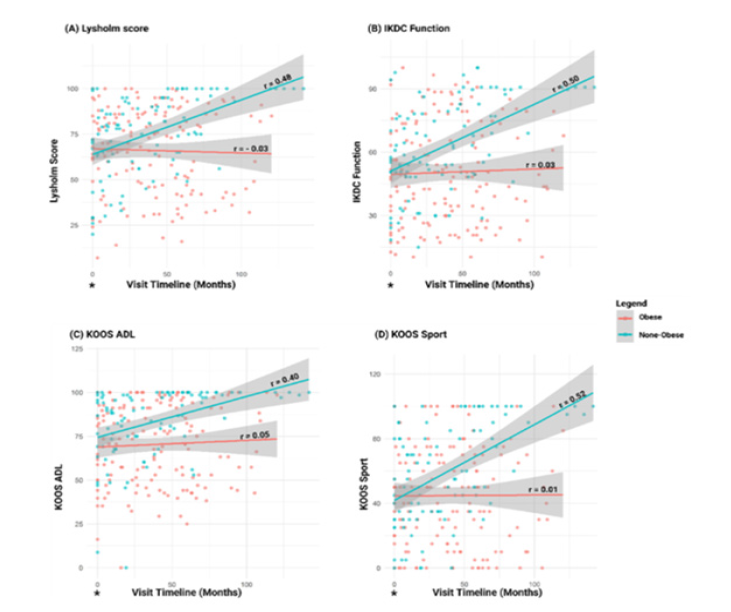

Knee joint function: In assessing the knee joint function, stability and activity limitation we evaluated Lysholm score, IKDC, KOOS Activities of Daily Living (ADL), and KOOS Sport assessment to determine the difference between obese and non-obese KOA patients. Among these PROMs, we noticed a consistent improvement in knee joint function among non-obese patients when compared to obese patients (Figure 3A-D). Table 2 also shows the IKDC t-test comparison between obese and non-obese group.

Figure 3:Linear model plots and correlation analysis of standardized PROMs for Lysholm Score (A), IKDC function (B), KOOS ADL (C), and KOOS Sport (D) in patients with knee Osteoarthritis (OA) over time, stratified by obesity status. A higher score for these PROMs indicates less symptomatic knee OA as reported by the patient. Baseline measurements (*) were used as reference points to assess longitudinal trends. IKDC=International Knee Documentation Committee, KOOS=Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, ADL=Activities of daily living. Red indicates obese group, and mint green indicates non-obese group.

General health: To determine how BMI correlates with overall health in KOA patients injected with Synvisc-One®, we used KOOS Quality of Life (QoL), physical component summary (PSF-12), and mental component summary (MSF-12). Linear model with person correlation showed an improvement for non-obese KOA patients post Synvisc-One® for KOOS QoL and PSF-12 (Figure 4A-C, Table 2). MSF-12 did not show any improvement prior to Synvisc-One® injection (Figure 4C). Correlation between obese and pre-obese patients did not show any significance, p>0.05 (Table 2).

Discussion

We demonstrated significant improvements in pain frequency and severity in non-obese patients, but these improvements were not demonstrated in the obese patients. Similarly, we demonstrated improvements in quality of life as measured by KOOS subscale. In fact, there were no instances where obese patients did better than non-obese patients in our study. KOA in obese patients is an ongoing topic in research. Although osteoarthritis was considered a result of trauma or aging, it is accepted that the pathophysiology is complex, and several factors can lead to the development and progression of OA [20]. One theory is that a strong inflammatory immune response from the patient plays a role in the development and regulation of OA. One study suggest that neutrophils are the primary cells involved in the development of OA while another highlights that adipose tissue is a major source of adipokines suggesting that these factors play a role in the regulation of inflammatory immune responses impacting articular cartilage [21,22]. The connection between these cellular inflammatory responses and the clinical symptoms of patients is crucial in the therapeutic target for pharmacologic modalities. Another factor to consider in the link between obesity and OA is heredity. OA progression and more severe joint damage may be a result of heredity, obesity, and injury combined due to similar pathogenetic phenotypes of patients with OA and adiposity [23].

Clinically, obesity is very important to consider when weighing treatment options for KOA, especially surgical treatment. Although, an exact BMI cutoff in obese patients tends to vary based on several factors, a recent study suggests that a significant increase in failure of TKA patients at one year occurs in patients with a BMI>50kg/ m2 [24]. Pre-operatively, clinicians should consider additional safeguards for obese patients, such as nutrition optimization and bariatric surgery. Intraoperative considerations include inadequate exposure, difficulty with implant alignment, and durable implant fixation [25]. Obesity is also linked to post-operative complications such as wound complications, medical complications, malalignment, dislocation, and early revision [8]. Class II obesity specifically, along with other factors such as Type II Diabetes Mellitus, hypertension, steroid therapy, and tobacco use, are related to an increased risk for periprosthetic joint infection post-operatively [26]. Despite additional risks, considerations, and complications, TKA in obese patients leads to improved function and quality of life. Therefore, individual circumstances should be prioritized for KOA patients considering surgical management [8].

For obese patients with less severe KOA or who may not be surgical candidates, non-operative treatment may provide relief for symptoms. Exercise and weight loss are strongly recommended along with topical and oral Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) [27]. However, obese patients with metabolic syndrome should avoid NSAIDs as well as corticosteroids and should consider antioxidant drugs such as ginger and copper to address both OA and metabolic syndrome [28]. Additionally, musculoskeletal corticosteroid injections have resulted in systemic side effects, including adrenal suppression or insufficiency, hyperglycemia, and osteoporosis [29]. Other injections, such as Intra-Articular (IA) Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) injections, are considered safe and most effective in young, active patients with low-grade OA [30].

Viscosupplementation offers a reliable non-operative treatment option for patients with KOA. Evidence supports the safety and benefit of multiple injections, with further research being conducted on this matter [10]. This treatment option in obese patients has previously been investigated, and one study reports there is no difference in pain score and pain decrease related to the weight status and radiological score [31]. Viscosupplementation has also been effective in treating OA symptoms in the hip but further research is required for a consensus in other joints [32,33]. In KOA patients, it has been associated with favorable healthcare cost-effectiveness as well as delays to TKA [34-36]. Synvisc GF- 20® (Sanofi Inc., Bridgewater, NJ) is a Hylan derivative used for the treatment of KOA and is considered an effective treatment for the management of OA [37,38]. Synvisc GF-20 is composed of Hylan A and B; Hylan A is composed of two to four hyaluronan molecules covalently coupled together remaining completely water soluble while more extensive, continuous cross-linking of the hyaluronan molecules produces a polymer gel known as hylan B. Hylan A and hylan B are combined in a 80:20 volume ratio to produce hylan G-F 20 or Synvisc® [39].

This cross-linked gel creates a high molecular weight (MW-6 million kDa) molecule with a much longer intra-articular halflife than other commercially available products. This product has demonstrated superiority in efficacy over lower MW hyaluronic acid molecules in KOA, with no increase in adverse effects [40]. The 7-day half-life demonstrated by Synvisc® is much longer than other products on the market with demonstrated hyaluronic acid on the articular cartilage surfaces and synovial tissues as well as in the synovial fluid at 7 days following injection [41]. The higher MW of Synvisc® than other products allow more molecule to attach along more CD-44 receptor sites on the synovial fibroblast [42]. This directly stimulates the fibroblast to produce more hyaluronic acid. Hyaluronic acid synthesis by the fibroblast creates the longterm 6+ months improvement in patient symptoms demonstrated by Synvisc®. Local adverse effects of hyaluronan products, such as pain and swelling, are considered minor and self-limiting but when they occur can look like a joint infection and are termed a pseudoseptic reaction [43,44]. In rare cases true infections from skin flora requiring medical treatment can occur but this is the case with all arthrocentesis procedures [12]. A published report describes a case of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by hyaluronic acid knee injection managed and followed by emergency department personnel [45]. Despite these reported adverse effects, Synvisc® is among the safest methods to treat KOA and reduces the need for NSAIDs and steroid injections [46].

The use of PROMs is common in patients with KOA; however, no previous literature links the use of PROMs in obese patients treated with viscosupplementation. Various PROMs are often used to assess patient function in those with KOA and other knee injuries and disorders. The Lysholm Knee Score has demonstrated acceptable psychometric parameters to assess function for patients with ligamentous injuries and chondral disorders [47,48]. The IKDC outcome score has been used in literature to quantify patient outcomes and conversion to TKA following meniscal procedures [49]. KOOS, SF-12, and other PROMs such as the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) have been useful in identifying patients predicted to require a TKA due to KOA [50]. This literature highlights the benefit of using PROMs in evaluating the clinical treatment of patients with KOA and other orthopedic disorders.

The current study explores viscosupplementation in a small sample size limiting the overall conclusions that can be drawn. Co-morbidities, Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grade, activity level and socioeconomic factors will also impact the effectiveness of viscosupplementation. This invites a larger evaluation of this treatment modality in the future.

Conclusion

Viscosupplementation remains a viable conservative option in the treatment of patients with KOA. However, BMI clearly plays a role in patient response to this modality. In addition to KL status and other factors, BMI should be considered in selecting patients most appropriate for the use of viscosupplementation. This study represents a comprehensive evaluation of a small subset of patients; considering the numbers of patients treated yearly with viscosupplementation a larger population-based assessment will help to further delineate the most ideal patient for viscosupplementation.

Author Contributions

Eden Schoofs, MD1: (1) The conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) Final approval of the version to be submitted; Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article, Provision of study materials or patients, Statistical expertise, Obtaining of funding, Administrative, technical, or logistic support, Collection and assembly of data

Jonathan Willard, MD1: (1) The conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) Final approval of the version to be submitted; Conception and design, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article, Collection and assembly of data

Savit Dhawan, BS2: (1) The conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) Final approval of the version to be submitted; Conception and design, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article, Collection and assembly of data

Graylin Jacobs, BS1: (1) The conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) Final approval of the version to be submitted; Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article, Provision of study materials or patients, Administrative, technical, or logistic support, Collection and assembly of data

David Otohinoyi, MD, PhD1: (1) The conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) Final approval of the version to be submitted; Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article, Provision of study materials or patients, Statistical expertise, Collection and assembly of data

Deryk Jones, MD1,2: (1) The conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) Final approval of the version to be submitted; Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of the data, Drafting of the article, Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content, Final approval of the article, Provision of study materials or patients, Statistical expertise, Administrative, technical, or logistic support, Collection and assembly of data

Financial Support and Disclosures

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Patient Consent/Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained for experimentation with human subjects. This investigation was approved by the Ochsner Health Human Research Protection Program, IRB No. 2012.205.

Competing Interest Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this work.

References

- Allen KD, Thoma LM, Golightly YM (2022) Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 30(2): 184-195.

- Bliddal H, Leeds AR, Christensen R (2014) Osteoarthritis, obesity and weight loss: Evidence, hypotheses and horizonsa scoping review. Obes 15(7): 578-586.

- Reyes C, Leyland KM, Peat G, Cyrus C, Nigel KA, et al (2016) Association between overweight and obesity and risk of clinically diagnosed knee, hip, and hand osteoarthritis: A population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol 68(8): 1869-1875.

- Koliaki C, Dalamaga M, Liatis S (2023) Update on the obesity epidemic: After the sudden rise, is the upward trajectory beginning to flatten? Curr Obes Rep 12(4): 528.

- Emmerich SD, Fryar CD, Stierman B, Cynthia LO (2024) Obesity and severe obesity prevalence in adults: United states, August 2021-August 2023. NCHS Data Brief (508): 10.

- Sørensen TIA, Martinez AR, Jørgensen TSH (2022) Epidemiology of obesity. Handb Exp Pharmacol 274: 3-27.

- Michael JW, Schlüter BKU, Eysel P (2010) The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Dtsch Arztebl Int 107(9): 152-162.

- Kulkarni K, Karssiens T, Kumar V, Hemant P (2016) Obesity and osteoarthritis. Maturitas 89: 22-28.

- Mora JC, Przkora R, Cruz AY (2014) Knee osteoarthritis: Pathophysiology and current treatment modalities. J Pain Res 11: 2189-2196.

- Peck J, Slovek A, Miro P, Neeraj V, Blake T, et al. (2021) A comprehensive review of viscosupplementation in osteoarthritis of the knee. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 13(2): 25549.

- Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, et al. (2006) Viscosupplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006(2): CD005321.

- Eisenberg Center at Oregon Health & Science University (2009) Three treatments for osteoarthritis of the knee: Evidence shows lack of benefit. In: Comparative Effectiveness Review Summary Guides for Clinicians [Internet]. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Maryland, USA.

- Davis AM, King LK, Stanaitis I, Hawker GA (2022) Fundamentals of osteoarthritis: Outcome evaluation with patient-reported measures and functional tests. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 30(6):775-785.

- Lysholm J, Gillquist J (1982) Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med 1982 10(3): 150-154.

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD (1996) A 12-Item Short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care 34(3): 220-233.

- Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, Harner CD, Kurosaka M, et al. (2001) Development and validation of the international knee documentation committee subjective knee form. Am J Sports Med 29(5): 600-613.

- Roos EM, Roos HP, Lohmander LS, Ekdahl C, Beynnon BD (1998) Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)-Development of a self-administered outcome measure. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 28(2): 88-96.

- Weir CB, Jan A (2023) BMI Classification Percentile and Cut Off Points. StatPearls Publishing, Florida, USA.

- Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd Edition), L Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, Michigan, USA, pp. 1-567.

- Martel PJ (2004) Pathophysiology of osteoarthritis, Osteoarthritis Cartilage 12 Suppl A: S31-3.

- Nedunchezhiyan U, Varughese I, Sun AR, Xiaoxin W, Ross C, et al. (2022) Obesity, inflammation, and immune system in osteoarthritis. Front Immunol 13: 907750.

- Wang T, He C (2018) Pro-inflammatory cytokines: The link between obesity and osteoarthritis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 44: 38-50.

- Bliddal H (2020) Definition, pathology and pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Ugeskr Laeger 182(42): V06200477.

- Righolt CH, Armstrong ML, Turgeon TR, Eric RB, Jhase S (2025) Primary total knee arthroplasty in patients with BMI of ≥50 kg/m2: A cohort study with long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 107(13): 1472-1479.

- Martin JR, Jennings JM, Dennis DA (2017) Morbid obesity and total knee arthroplasty: A growing problem. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 25(3): 188-194.

- Rodriguez MEC, Delgado MAD (2022) Risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Med 11(20): 6128.

- Huffman KF, Ambrose KR, Nelson AE, Kelli DA, Yvonne MG, et al. (2024) The critical role of physical activity and weight management in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A narrative review. J Rheumatol 51(3): 224-233.

- Conrozier T (2020) How to treat osteoarthritis in obese patients? Curr Rheumatol Rev 16(2): 99-104.

- Kamel SI, Rosas HG, Gorbachova T (2024) Local and systemic side effects of corticosteroid injections for musculoskeletal indications. AJR Am J Roentgenol 222(3): e2330458.

- Jang S, Lee K, Ju JH (2021) Recent updates of diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment on osteoarthritis of the knee. Int J Mol Sci 22(5): 2619.

- Conrozier T, Eymard F, Chouk M, Xavier C (2019) Impact of obesity, structural severity and their combination on the efficacy of viscosupplementation in patients with knee osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 20(1): 376.

- Migliore A, Gigliucci G, Alekseeva L, Raveendhara R, Tomasz B, et al. (2021) Systematic literature review and expert opinion for the use of viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid in different localizations of osteoarthritis. Orthop Res Rev 13: 255-273.

- Patel R, Orfanos G, Gibson W, Banks T, McConaghie G, et al. (2024) Viscosupplementation with high molecular weight hyaluronic acid for hip osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised control trials of the efficacy on pain, functional disability, and the occurrence of adverse events. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 91(2):109-119.

- De Rezende MU, De Campos GC (2015) Viscosupplementation. Rev Bras Ortop 47(2): 160-164.

- Concoff A, Niazi F, Farrokhyar F, Akram A, Jeffrey R, et al. (2021) Delay to TKA and costs associated with knee osteoarthritis care using intra-articular hyaluronic acid: Analysis of an administrative database. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 14: 1179544121994092.

- Ong KL, Runa M, Lau E, Altman R (2019) Is Intra-articular injection of synvisc associated with a delay to knee arthroplasty in patients with knee osteoarthritis? Cartilage 10(4):423-431.

- Migliore A, Giovannangeli F, Granata M, Laganà B (2010) Hylan g-f 20: Review of its safety and efficacy in the management of joint pain in osteoarthritis. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord 3: 55-68.

- Wobig M, Dickhut A, Maier R, Vetter G (1998) Viscosupplementation with hylan G-F 20: A 26-week controlled trial of efficacy and safety in the osteoarthritic knee. Clin Ther 20(3): 410-423.

- Balazs EA, Leshchiner EA (1989) Hyaluronan, its crosslinked derivative-Hylan-and their medical applications. Inagaki H, Phillips GO. Cellulosics Utilization: Research and Rewards in Cellulosics. Proceedings of Nisshinbo International Conference on Cellulosics Utilization in the Near Future, Elsevier Applied Science, New York, USA, pp. 233-241.

- Zhao H, Liu H, Liang X, Yi L, Junhu W, et al. (2016) Hylan G-F 20 versus low molecular weight hyaluronic acids for knee osteoarthritis: A meta-analysis. BioDrugs 30(5): 387-396.

- Brown TJ, Laurent UB, Fraser JR (1991) Turnover of hyaluronan in synovial joints: elimination of labelled hyaluronan from the knee joint of the rabbit. Exp Physiol 76(1): 125-134.

- Smith MM, Ghosh P (1987) The synthesis of hyaluronic acid by human synovial fibroblasts is influenced by the nature of the hyaluronate in the extracellular environment. Rheumatol Int 7(3): 113-122.

- Aydın M, Arıkan M, Toğral G, Varış O, Aydın G (2017) Viscosupplementation of the knee: Three cases of acute pseudoseptic arthritis with painful and irritating complications and a literature review. Eur J Rheumatol 4(1): 59-62.

- Goldberg VM, Coutts RD (2004) Pseudoseptic reactions to hylan viscosupplementation: Diagnosis and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res (419): 130-137.

- Ntavari N, Mavrovounis G, Gravani A, Vasiliki S, Angeliki VR, et al. (2025) Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by hyaluronic acid knee injection: A case report. J Emerg Nurs 51(1): 20-26.

- Andrzejewski T, Gołda W, Gruszka J, Piotr J, Jeske P, et al (2003) Assessment of synvisc treatment in osteoarthritis. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 5(3): 379-90.

- Kocher MS, Steadman JR, Briggs KK, William IS, Richard JH, et al (2004) Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm knee scale for various chondral disorders of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 86(6): 1139-45.

- Briggs KK, Lysholm J, Tegner Y, William G, Mininder S, et al. (2009) The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the lysholm score and tegner activity scale for anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee: 25 years later. Am J Sports Med 37(5):890-897.

- Shephard L, Abed V, Nichols M, Andrew K, Camille K, et al. (2023) International knee documentation committee (ikdc) is the most responsive patient reported outcome measure after meniscal surgery. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 5(3): e859-e865.

- Faschingbauer M, Kasparek M, Schadler P, Trubrich A, Urlaub S, et al. (2017) Predictive values of WOMAC, KOOS, and SF-12 score for knee arthroplasty: Data from the OAI. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 25(11): 3333-3339.

© 2025 Deryk Jones. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)