- Submissions

Full Text

Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research Studys

Illinois K-12 Public School Personnel Readiness for Supporting Student Mental Health

Jessica Reichert1*, Ryan Maranville2, Jing Wang3 and Ebonie Epinger4

11Senior Research Scientist and Manager of the Center for Justice Research and Evaluation, Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, USA

22Research Scientist, Center for Justice Research and Evaluation, Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, USA

33Senior Research Scientist, Center for Justice Research and Evaluation, Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, USA

4Assistant Research Scientist for the Center for Prevention Research and Development, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, USA

*Corresponding author: Jessica Reichert, Senior Research Scientist and Manager of the Center for Justice Research and Evaluation, Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority 60 E. Van Buren St., Suite 650 Chicago, IL 60605, Chicago, USA

Submission: August 30, 2025;Published: September 16, 2025

ISSN 2639-0612Volume9 Issue 3

Abstract

With rising rates of mental health disorders among youth, schools have become essential settings for early identification and intervention, despite often facing resource limitations. This study surveyed 160 Illinois K-12 public school personnel to assess their knowledge of mental health, preparedness, and use of mental health skills. Regression analyses examined how individual-level demographic and professional characteristics influenced these outcomes. University-level training, prior completion of professional workshops, and roles in administration or healthcare were positively associated with higher pre-training mental health knowledge. These factors, along with roles in physical or mental/behavioural health, were also linked to greater self-reported preparedness and responsiveness. However, no significant associations were found between personnel characteristics and their reported use or application of mental health skills. These findings underscore the importance of targeted, role-specific training to strengthen school personnel’s capacity to support student mental health and promote more inclusive and responsive school environments.

Keywords:Youth; Mental health; Public schools; Teachers; Administrators; Training

Introduction

Mental health disorders, a clinically significant disturbance in an individual’s cognition, emotional regulation, or behaviour, affect a significant portion of American children. ADHD, anxiety, behaviour problems, and depression are the most prevalent [1,2]. Suicide continues to remain a critical concern and ranks as the second leading cause of death among youth over 10 [3]. Despite the prevalence of these issues, approximately half of the children requiring mental health treatments do not receive them [2,4].

Due in part to a lack of sufficient mental health support in the community, schools are positioned to play a vital role in the early identification of, and support for, emotional and mental health problems, especially the early signs or symptoms of mental disorders that are not frequent or severe enough to meet the criteria for a diagnosis [4-7]. This is important, as early and appropriate intervention yields more positive outcomes and can prevent unnecessary or over-medicalization and institutionalization of children and youth [8]. Mental, emotional, and behavioural disorders typically begin to present symptoms in adolescence. At the same time, individuals are young, and early interventions provide an opportunity for prevention and assistance prior to the full onset of mental health disorders [4].

Roles of school personnel in student mental health

Students spend significant amounts of time in the school setting, making educators and other staff uniquely positioned to recognize early warning signs or changes in a student’s behaviour or emotional well-being. Duong and colleagues [9] found that while school mental health resources can help youth, only a slight majority of public schools (55%) assess students for mental health disorders, with just 42% providing mental health treatment. They also explained that despite limited school resources, schools remain one of the most common providers of mental health services for all youth, including those with known mental health disorders.

However, the capacity of school personnel to effectively support student mental health varies widely. Differences in occupational roles, the nature of relationships with students, and access to mental health training all influence staff readiness and responsiveness. Moreover, the existing literature highlights a persistent researchto- practice gap in implementing mental health practices in school settings [10]. This includes a limited understanding of how individual-level characteristics, such as previous mental health training and job role, affect practice outcomes and a need for clearer strategies to optimize training implementation [11].

Mental health training for school personnel

Teachers and other school staff have reported a lack of experience, knowledge, and training in supporting the mental health needs of youth [12,13]. This can include a deficit in knowledge of symptoms, how to intervene appropriately, and familiarity with the availability and accessibility of local mental health services to make necessary referrals. Further, a lack of mental health literacy among school employees can contribute to stigma and misinformed beliefs toward children with mental health disorders, thereby contributing to adverse outcomes (e.g., poor academic achievement, isolation, and lack of identification or treatment) [14].

The lack of knowledge and skills among educators regarding youth mental health disorders is partially attributable to insufficient pre-service (i.e., pre-teacher) training and education. For instance, a 2024 literature review of school-based mental health promotion and professional development found vague teacher certification standards, including variations in pre-service teacher curricula or standards regarding mental health training across the United States. They described training at the intersection of mental health and classroom management as primarily occurring in a workshop or professional development setting, and therefore, varying by school district or geography. In other words, all school staff (i.e., teachers, administrators, and support staff) vary in their training, certification, knowledge, and experience managing youth mental health in their classrooms or professional duties [15].

Given the need to support youth mental health, the opportunities for positive contact and outreach within schools, and variability in staff skills and knowledge, many have examined the impact of school-based training, such as workshops and professional development programs. As one might expect, research and evaluation literature indicate that training programs can enhance participants’ knowledge, confidence, and attitudes toward mental health [11,16-18]. Moreover, even relatively short (one hour or less) and singular online training has been shown to improve confidence and attitudes toward mental health preparedness among preservice teacher training participants [19].

Current study

Despite the important role school personnel play in supporting youth mental health, the specific dimensions of their roles and the factors that may influence them, such as demographics, education, prior training, and job position, have not been systematically studied. Therefore, we used survey data from 160 public school personnel from Illinois, encompassing grades K-12. This survey was conducted before participants took part in YMHFA training and spanned from December 2020 to September 2023. We gathered and analysed the data on school personnel’s mental health knowledge, preparedness, responsiveness, and experiences assisting with student mental health issues. The main research questions for our study were:

A. How knowledgeable are school personnel about mental health

assistance?

B. How prepared are school personnel in applying mental health

skills?

C. To what extent are school personnel responsive to student

mental health needs?

D. Are factors such as demographics, education, previous

training, and job positions associated with school personnel’s

knowledge, confidence, and experience in mental health skills?

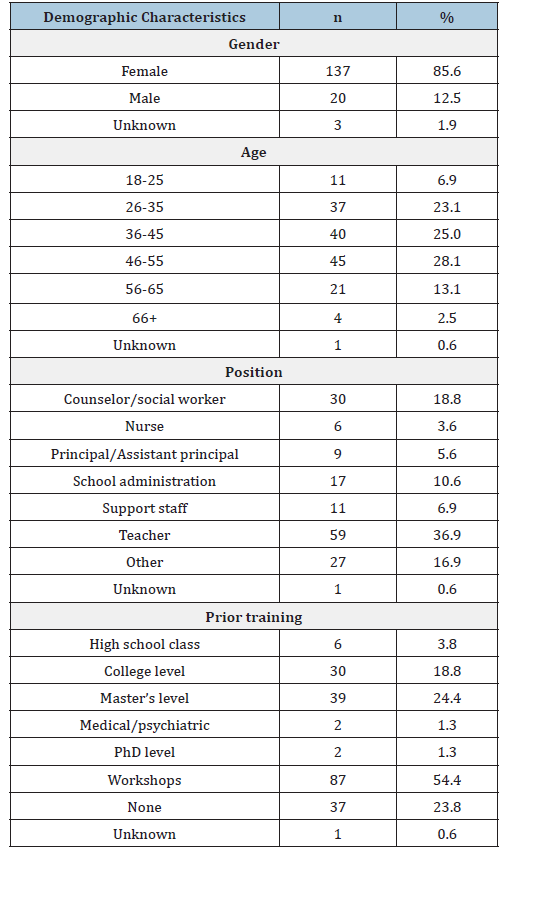

Table 1: Demographics of sample.

Note: The sample was 160 school personnel. Respondents could have more than one type of prior training.

Measures

Our survey items and answers were sourced from the training curriculum in the YMHFA manual [21,22] and based on items in prior YMHFA studies [20,23–26]. YMHFA is an 8-hour training program designed to teach adults, including school staff, how to support youth experiencing mental health issues. The survey items were designed to assess the respondents’ pre-training status. The survey items align with Jorm and colleagues’ [27,28] mental health literacy model and Bandura’s [29] self-efficacy theory, which underpins the training’s design. As referenced above, prior studies validate these as standard evaluation metrics in YMHFA research. The survey consisted of 28 items: 4 items on respondents’ demographic characteristics (gender, age), job title, and previous mental health training; 10 items gauging mental health knowledge; 4 items examining their youth mental health preparedness and responsiveness; and 4 items on their experience applying mental health skills.

Mental health knowledge

Mental health knowledge is an established concept in the field of public health. Mental health knowledge encompasses the ability to identify specific types of disorders or psychological distress, as well as knowledge or beliefs surrounding their causes, risk factors, and interventions (e.g., self-help or professional) [27,28,30]. In our survey, we provided ten items related to mental health knowledge. Two items used vignettes, instructing participants to select the correct response from among multiple options, with only one correct answer. Seven knowledge items provided three response options: agree, disagree, or do not know, and had three correct responses. Lastly, one item asked individuals to self-evaluate their knowledge using a 5-point Likert scale.

Mental health preparedness and responsiveness

Self-efficacy, a belief in one’s ability to organize and execute actions, is a key concept in behavioural theory [29,31]. Using four survey items, our survey examined school personnel’s preparedness and responsiveness to youth mental health needs. These items asked respondents to self-evaluate their comfort levels, confidence, and likelihood of reporting or intervening when witnessing behaviour that signalled youth mental health concerns, using a 5-point Likert scale.

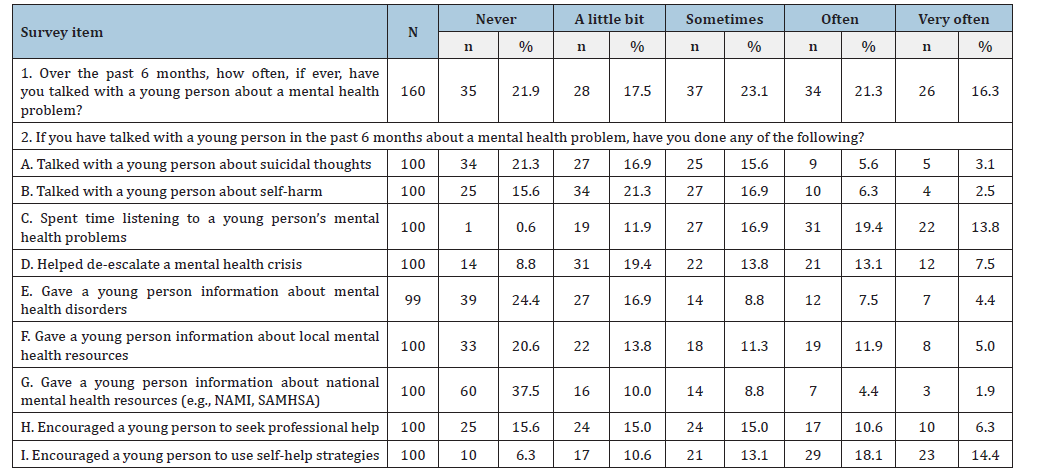

Use of mental health skills

Survey respondents were asked to respond to their actions in the previous six months in situations necessitating their intervention. We provided ten items about their recent experience using mental health skills. Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

Analyses

We conducted descriptive statistics and regression analyses, including multiple linear regression, Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, ordinal logistic regression, and binary logistic regression. Each test was tailored to best fit the nature of the respective set of dependent variables.

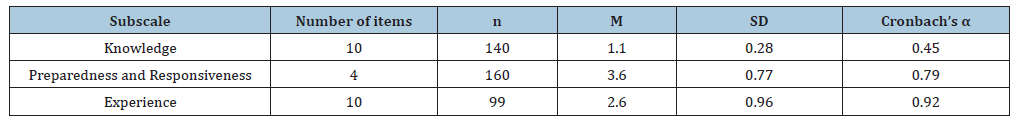

In our regression analyses, we used subscales as the dependent variables. The subscales comprise groupings of survey items focusing on mental health, including Knowledge, Confidence, and Skills (Table 2). Cronbach’s α was used to assess each subscale’s reliability, or internal consistency, with a minimum threshold of 0.7 considered acceptable for internal consistency. We found that the Knowledge subscale had low internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.45). The other two subscales of Confidence and Skills had acceptable internal reliability scores, with Cronbach’s α values of 0.79 and 0.92, respectively. Therefore, the multiple linear regressions used the mean composite scores of both subscales as continuous dependent variables.

Table 2: Subscales of school personnel’s knowledge, perception, and experience of mental health skills.

Note: Subscales from a survey of public school personnel. The response rate was 87.5% for the knowledge subscale, 100% for the perception subscale, and 61.9% for the experience subscale.

Since a composite score is not feasible for the Knowledge subscale, we used two different models for the analyses: ordinal regression and binary logistic regression. Among the ten Knowledge items on the survey, we used an ordinal regression model for the self-rated knowledge item measured on a 5-point Likert scale and binary logistic regression for the items with binary responses.

The independent variables in our analyses included gender (1 = male, 0 = female), age (continuous), prior training (workshop and university-level, coded 1 = yes, 0 = no, with the third category “other training” omitted), and job position 1 = yes, 0 = no for each job category, with the third category omitted). We categorized the sample into three job position groups: 1) Administrators, 2) Teachers, and 3) Physical, Mental, or Behavioural Health. We referenced the ISBE’s Employment Information System for guidance on designating respondents’ positions as administrative or teaching [32]. Administrators included principals, assistant principals, superintendents, supervisors, and directors of programs or services. Teachers included general educators, substitute teachers, and special education teachers. Physical, mental, or behavioural health professionals included school psychologists, counsellors, social workers, therapists, nurses, student interventionists, and mental health coordinators.

Results

Mental health knowledge

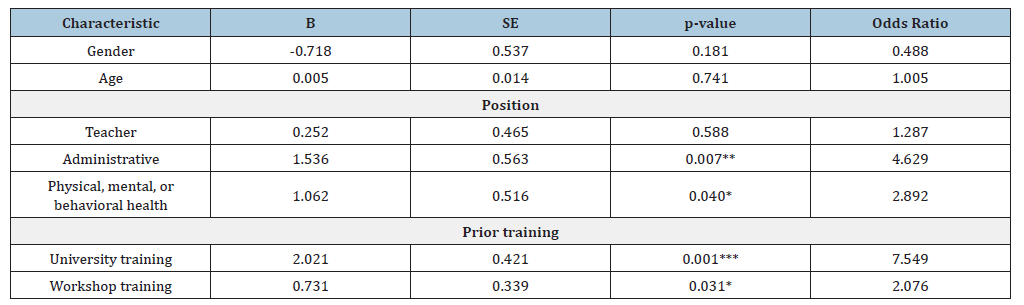

One survey item allowed respondents to self-evaluate their mental health knowledge. When asked, “How much do you know about mental health disorders in young persons,” nine (5.6%) selected “A great deal,” 17 (10.6%) selected “A lot,” 66 (41.3%) selected “A moderate amount,” 64 (40%) selected “A little,” and four (2.5%) selected “Nothing at all.” We used ordinal regression and odds ratios for each predictor variable to show the odds of being in a higher category of the outcome variable for a one-unit increase in the predictor. We found the odds for school administrators to report a higher level of mental health knowledge were 4.6 times greater than those of non-administrators; behavioural, physical, or mental health staff had 2.9 times greater odds of feeling they knew more (have a higher level of knowledge) about mental health disorders in young people than other personnel. Regarding the prior training, school personnel who completed university-level training had 7.6 times greater odds of reporting a higher level of youth mental health knowledge than those who did not; those who completed workshop-level training had two times greater odds of reporting a higher level of youth mental health knowledge than those who had not (Table 3).

Table 3: Ordinal regression on self-evaluation of knowledge.

Note: The sample size was 160 school personnel. B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error. *p < .05. **p < .01.***p < .001.

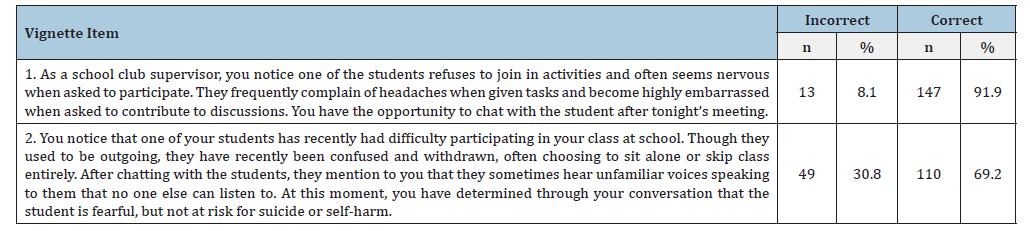

We also used two vignettes to test mental health knowledge (Table 4). While a large majority provided the correct response to item 1, 31% provided an incorrect response to item 2. As determined by logistic regression models, we found no significant relationship between the demographics of school personnel and their responses to the vignette items.

Table 4: Responses to mental health knowledge vignettes.

Note: The sample size was 160 school personnel for survey item 1 and 159 for survey item 2. The correct response to item 1 was, “Ask the student what you can do to help them feel more comfortable at meetings.” The correct response to item 2 was, “Provide them reassurance and listen to their concerns.”

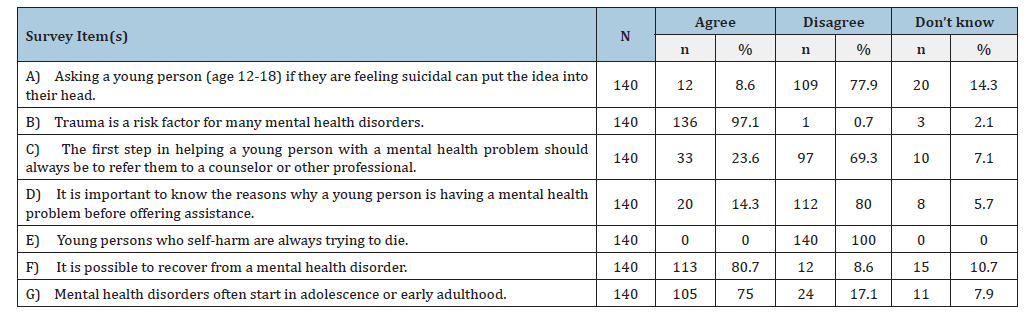

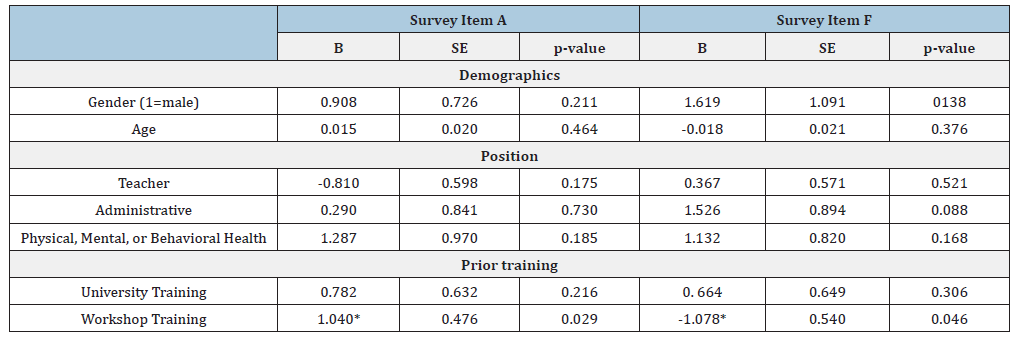

Most respondents were correct on the seven items measuring mental health knowledge (Table 5). However, about one-fourth responded incorrectly to the item about referrals for mental health problems (item 3), and either were incorrect or did not know the answer to the item about young people and suicide (item 1). We examined the demographics of school personnel and their responses to each survey item. Using logistic regression, we found workshop-level training increased knowledge on two items- Item A about youth feeling suicidal (p = 0.029) and Item F on recovery from a mental health disorder (p = 0.046) (Table 6). Due to the low Cronbach’s α (0.45), these survey items on Knowledge are not analysed aggregately with a composite score.

Table 5: Responses to statements on mental health.

Note: Sample size was 140. “Disagree” is the correct answer for items A, C, D, & E. “Agree” is the correct answer for items B, F, & G.

Table 6: Binary logistic regressions on statements on mental health.

Note: Sample size was 140 for survey items A and F. B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < 0.001.

Mental health confidence

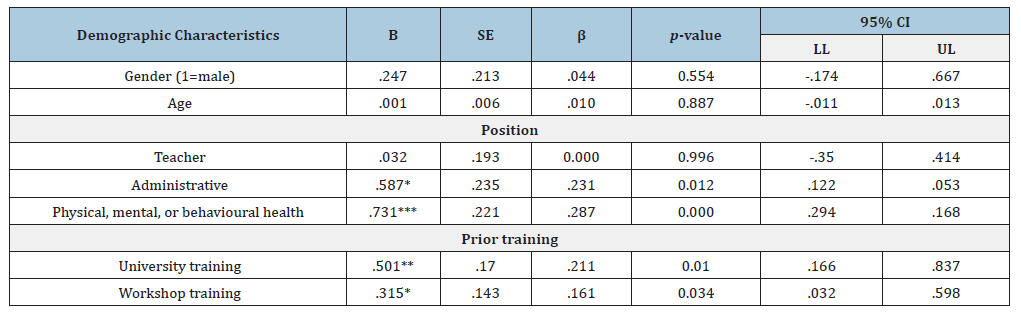

Four survey items inquired about respondents’ preparedness and responsiveness in assisting with mental health issues among youth (Table 7). These included asking about their confidence, comfort levels, and the likelihood of intervening in crises or reporting concerns involving the youth they work with.

Table 7: Responses to mental health preparedness and responsiveness items.

Note: The sample size was 160 school personnel.

The four survey items worked together well (Cronbach’s α = 0.79) to provide a stable and consistent measure of confidence (Table 9). Therefore, the mean composite score of these four items is used as the dependent variable in our multiple regression. We found significant associations between staff positions, prior training, and the confidence of school personnel in assisting with student mental health issues (Table 8). Those in administrative (p = 0.014) or physical, mental, or behavioural health staff (p = 0.001) positions, as well as those with prior workshop (p = 0.029) or university-level (p = 0.004) training, reported greater levels of confidence regarding mental health.

Table 8: Multiple regression on preparedness and responsiveness of mental health skills.

Note: The sample size was 160 school personnel. B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error; β = standardized coefficient; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < 0.001.

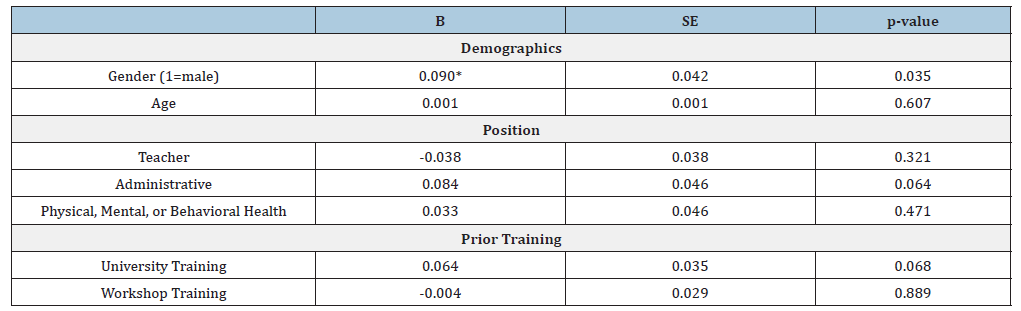

Table 9: Ordinary least squares regression on statements on mental health.

Note: Sample size was 140. B = unstandardized coefficient; SE = standard error. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < 0.001.

Use of mental health skills

Finally, respondents completed ten items about their experience using skills associated with youth mental health (Table 10). Similarly, we conducted a multiple linear regression analysis with the mean composite score of these items (Cronbach’s α = 0.92) as the dependent variable. However, we found no significant association between the school personnel’s demographic characteristics, position, and prior training and their use of mental health skills or experience in assisting students.

Table 10: Responses to use of mental health skills items.

Note: The sample size ranges from 99 to 160 school personnel who responded to the items.

Discussion

Mental health literacy of school personnel

We found that overall, school personnel had foundational knowledge of mental health related to youth. Most of the school personnel answered the mental health knowledge items correctly, and just over half shared that they knew ‘a lot’ or ‘a moderate amount’ about mental health disorders in young persons. However, about one-fourth were incorrect in answering that the first step to helping young people with a mental health problem is to refer them to a professional. Our data revealed that school personnel needs to be informed about referral procedures and courses of action that yield the best results.

For instance, professionals are not the first or only resource, and they themselves can serve an important supportive role for youth with current or future mental health problems. This is a recommended practice for a few reasons. First, referring youth to professional help can be intimidating, whereas school personnel could offer a safe space for open communication [33]. Second, intervention through supportive conversations may be enough to manage mild youth mental health concerns, such as everyday student anxieties [34]. Ultimately, school personnel are wellpositioned to establish trust and rapport, providing valuable emotional support and guidance independently or in conjunction with professional assistance [35]. Overall, schools can help their staff promote mental health literacy, serve as supportive roles to youth, and refer them to professionals as needed [36].

Mental health training for school personnel

In terms of intervening to help youth, our results were mixed. Respondents were confident they could help and were likely to report youth behavioural health concerns. However, half or more did not have a strong comfort level talking to youth who are having a mental health problem, nor did they report a strong likelihood to intervene in mental health crises. Just over half of our sample of school personnel reported completing a prior workshop training. We found that completing workshop-level training was associated with correctly answering more mental health knowledge items than those who did not receive training. While we do not know which specific workshop training(s) were taken, this suggests that workshops may increase mental health knowledge. Furthermore, school personnel who had received prior workshop training reported increased preparedness and enhanced responsiveness regarding mental health compared to those without training. This aligns with previous research, which shows that workshops enhance the competency of school personnel, supporting efforts to improve student mental health outcomes [15,37].

When mental health training resources are limited, training should be prioritized for individuals most likely to benefit [11,38]. In addition, districts could consider offering evidence-based training within the school setting, developed in collaboration with educators and explicitly tailored to their needs. One example of this is the free Classroom WISE (Well-being Information and Strategies for Educators) self-paced online course designed to increase the mental health literacy of K-12 educators [39]. However, further research is needed to determine the optimal training dosage and better understand how characteristics influence mental health training, ultimately improving youth mental health outcomes.

Job position and mental health awareness

School job positions have different educational requirements to fulfil varying roles and responsibilities in the school environment. Our survey revealed that the role of public-school personnel has a significant impact on the mental health, knowledge and confidence of the youth they serve. Administrators and those in physical, mental, or behavioural health positions had more knowledge than those with other school job positions; administrators and staff in physical, mental, or behavioural health roles were associated with higher mental health preparedness and responsiveness. This is consistent with previous findings that school-based mental health professionals and administrators are more concerned about students’ mental health needs as compared to teachers [40]. These job roles, particularly those in health-related fields, may have benefited from additional mental health training that increased mental health literacy. Therefore, focused training on non-administrative or health-related school personnel may lead to greater knowledge gain and overall benefits for students [38], and school-wide initiatives can help foster a shared commitment across staff roles [40].

More trained medical personnel, such as psychiatrists and nurses, can work alongside teachers and administrators to create a multidisciplinary team [41]. Nurses, who may be underutilized in this arena, can provide direct care (e.g., counselling, medication management), manage referrals and coordination with other mental health providers, and assist with identification (e.g., conducting screenings to identify needs) [42]. Ultimately, school nurses and other medical staff are an important component in supporting positive mental health outcomes for students and are assets to teachers as they become better trained [43]. This shared commitment across personnel within schools can lead to collaboration and partnerships among staff in addressing mental health issues and providing better care for students.

Study limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, using a convenience sample may limit the generalizability of our findings to the broader population of school personnel in Illinois or other states, as the volunteer participants may have been more invested in youth mental health. Second, the selfreported nature of the survey data may introduce potential biases, such as social desirability or recall bias, particularly in items related to past experiences and the self-evaluation of knowledge and skills. Third, the study’s cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences about the relationships between variables. Finally, although we examined several demographic and professional characteristics, we lacked data on specific demographic characteristics (e.g., race and ethnicity) and other potentially influential factors (e.g., personal mental health experiences and school policies). Future research should address these limitations to provide a more comprehensive understanding of school personnel’s mental health literacy and its impact on student support.

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the mental health knowledge, preparedness, responsiveness and experience of Illinois K-12 public school personnel. Our findings suggest schools should educate their personnel about the importance of their supportive role in addressing youth mental health challenges because school staff, including teachers and administrators, can promote mental health literacy by creating a safe space for open communication, addressing mild concerns, fostering trust with students, offering valuable emotional support, and referring students to professionals when necessary. Our findings underscore the importance of targeted mental health training programs for school staff, particularly those in non-administrative or non-healthrelated roles. The results indicate that prior workshop training and university-level education are associated with higher levels of mental health knowledge and self-reported preparedness to assist students with mental health issues.

Additionally, job positions, particularly those in administrative and health-related roles, influenced mental health literacy and confidence in responding to student mental health concerns. These findings have important implications for school mental health policies and practices. They suggest that investments in comprehensive mental health training could significantly enhance the school’s capacity to support student mental health. The study underscores the need for ongoing research to bridge the gap between mental health knowledge and its practical application in schools. Evidence-based training in school settings should be developed in collaboration with educators and tailored to their specific needs. Further research is needed to better understand how individual and contextual factors influence mental health training, to identify the most effective training approaches, and ultimately to improve youth mental health outcomes.

Ethical Consideration/Information

The original study for which the data were collected was conducted as part of an evaluation of a government-funded training program and was not primarily intended to contribute to generalizable research. As such, the Institutional Review Board secretary of the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority determined that the project did not require formal IRB review.

Data Availability Statement

Data may be available upon request.

Declaration of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All authors must share responsibility for the final version of the work submitted and published.

References

- Bitsko RH, Claussen AH, Lichstein J, Black LI, Jones SE, et al. (2022) Mental health surveillance among children-United States, 2013-2019. MMWR Supplements 71(2): 1-42.

- Whitney DG, Peterson MD (2019) US national and state-level prevalence of mental health disorders and disparities of mental health care use in children. JAMA Pediatr 173(4): 389-391.

- Stone DM, Jones CM, Mack KA (2021) Changes in suicide rates-United States, 2018-2019. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 70(8): 261-268.

- National Research Council & Institute of Medicine (2009) Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioural disorders among young people: Progress and possibilities, p. 592.

- Kern L, Mathur SR, Albrecht SF, Poland S, Rozalski M, et al. (2017) The need for school-based mental health services and recommendations for implementation. School Mental Health 9(3): 205-217.

- Rossen E, Cowan KC (2014) Improving mental health in schools. Phi Delta Kappan 96(4): 8-13.

- Stephan SH, Sugai G, Lever N, Connors E (2015) Strategies for integrating mental health into schools via a multitiered system of support. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 24(2): 211-231.

- World Health Organization (2009) Mental health of adolescents.

- Duong MT, Bruns EJ, Lee K, Cox S, Coifman J, et al. (2021) Rates of mental health service utilization by children and adolescents in schools and other common service settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 48(3): 420-439.

- Reinke WM, Stormont M, Herman KC, Puri R, Goel N (2011) Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher perceptions of needs, roles, and barriers. School Psychology Quarterly 26(1): 1-13.

- Elligson RL, Childs KK, Gryglewicz K (2021) Youth Mental Health First Aid: Examining the influence of pre-existing attitudes and knowledge on training effectiveness. The Journal of Primary Prevention 42(6): 549-565.

- Deaton JD, Ohrt JH, Linich K, Wymer B, Toomey M, et al. (2022) Teachers’ experiences with K-12 students’ mental health. Psychology in the Schools 59(5): 932-949.

- Frauenholtz S, Williford A, Mendenhall AN (2015) Assessing school employees’ abilities to respond to children’s mental health needs: Implications for school social work. School Social Work Journal 39(2): 46-62.

- Frauenholtz S, Mendenhall AN, Moon J (2017) Role of school employees’ mental health knowledge in interdisciplinary collaborations to support the academic success of students experiencing mental health distress. Children and Schools 39(2): 71-79.

- Dinnen HL, Litvitskiy NS, Flaspohler PD (2024) Effective teacher professional development for school-based mental health promotion: A review of the literature. Behavioral Sciences 14(9): 780.

- Anderson M, Werner-Seidler A, King C, Gayed A, Harvey SB, et al. (2019) Mental health training programs for secondary school teachers: A systematic review. School Mental Health 11(3): 489-508.

- Jorm AF, Kitchener BA, Sawyer MG, Scales H, Cvetkovski S (2010) Mental health first aid training for high school teachers: A cluster randomized trial. BMC Psychiatry 10: 51.

- Noltemeyer A, Huang H, Meehan C, Jordan E, Morio K, et al. (2020) Youth Mental Health First Aid: Initial outcomes of a statewide rollout in Ohio. Journal of Applied School Psychology 36(1): 1-19.

- Green JG, Levine RS, Oblath R, Corriveau KH, Holt MK, et al. (2020) Pilot evaluation of preservice teacher training to improve preparedness and confidence to address student mental health. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health 5(1): 42–52.

- Reichert J, Adams S, Green E (2024) Evaluation of youth mental health first aid trainings for Illinois schools, 2022-2023. Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority.

- Kelly CM, Kitchener BA, Jorm AF (2017) Youth mental health first aid manual. In: (4th edn), Mental Health First Aid International.

- National Council for Mental Wellbeing (2025) Youth Mental Health First Aid.

- Banh MK, Chaikind J, Robertson HA, Troxel M, Achille J, et al. (2019) Evaluation of mental health first aid USA using the mental health beliefs and literacy scale. American Journal of Health Promotion 33(2): 237-247.

- Haggerty D, Carlson JS, McNall M, Lee K, Williams S (2019) Exploring youth mental health first aider training outcomes by workforce affiliation: A survey of Project AWARE participants. School Mental Health 11(2): 345-356.

- Marsico KF, Wang C, Liu JL (2022) Effectiveness of youth mental health first aid training for parents at school. Psychology in the Schools 59(8): 1701-1716.

- Rose T, Leitch J, Collins KS, Frey JJ, Osteen PJ (2019) Effectiveness of youth mental health first aid USA for social work students. Research on Social Work Practice 29(3): 291-302.

- Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, et al. (1997) ‘Mental health literacy’: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust 166(4): 182-186.

- Jorm AF (2000) Mental health literacy. Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 177(5): 396-401.

- Bandura A (1977) Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 84(2): 191-215.

- Sampaio F, Gonçalves P, Sequeira C (2022) Mental health literacy: It is now time to put knowledge into practice. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(12): 7030.

- Artino AR (2012) Academic self-efficacy: From educational theory to instructional practice. Perspectives on Medical Education 1(2): 76-85.

- Illinois State Board of Education (2023) Illinois State Board of Education employee information systems data elements, approved codes, and indicators.

- Radez J, Reardon T, Creswell C, Lawrence PJ, Evdoka-Burton G, et al. (2021) Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 30(2): 183-211.

- Hellström L, Beckman L (2021) Life challenges and barriers to help seeking: Adolescents’ and young adults’ voices of mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(24): 13101.

- Rickwood DJ, Deane FP, Wilson CJ (2007) When and how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems? The Medical Journal of Australia 187(S7): S35-S39.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2025) Promoting mental health and well-being in schools: An action guide for school and district leaders.

- Powers JD, Wegmann K, Blackman K, Swick DC (2014) Increasing awareness of child mental health issues among elementary school staff. Families in Society 95(1): 43-50.

- Geierstanger S, Yu J, Saphir M, Soleimanpour S (2024) Youth Mental Health First Aid training: Impact on the ability to recognize and support youth needs. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 51(4): 588-598.

- Semchuk JC, McCullough SL, Lever NA, Gotham HJ, Gonzalez JE, et al. (2023) Educator-informed development of a mental health literacy course for school staff: Classroom well-being information and strategies for educators (Classroom WISE). Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(1): 35.

- Moon J, Williford A, Mendenhall A (2017) Educators’ perceptions of youth mental health: Implications for training and the promotion of mental health services in schools. Children and Youth Services Review 73: 384-391.

- Olson PM, Pacheco MR (2005) Bipolar disorder in school-age children. The Journal of School Nursing 21(3): 152-157.

- Minnesota Department of Health (2025) Nursing role in managing mental health needs of students. Minnesota Department of Public Health.

- Bohnenkamp JH, Stephan SH, Bobo N (2015) Supporting student mental health: The role of the school nurse in coordinated school mental health care. Psychology in the Schools 52(7): 714-727.

© 2025 Jessica Reichert, This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)