- Submissions

Full Text

Open Journal of Cardiology & Heart Diseases

Pre-Procedural Anxiety in TEER Patients with the Impact of Virtual Reality and the Role of Timing

Abby E Geerlings, Krystien V Lieve, Marja Holierook, Elena V Chekanova, Linda Veenis, Berto J Bouma* and Jan Baan*

Department of Cardiology, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam Cardiovascular Sciences, Netherlands

*Corresponding author: Berto J Bouma, Heart Center, Amsterdam UMC, Netherlands

Submission: November 13, 2025;Published: January 21, 2026

ISSN 2578-0204Volume5 Issue 2

Abstract

Aims: Pre-procedural anxiety can negatively impact outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous

cardiac interventions, but its role in Transcatheter Edge-To-Edge Repair (TEER) is unclear. This study

evaluates whether Virtual Reality (VR)-based patient education reduces anxiety in adults scheduled for

TEER.

Methods: In this single-center randomized controlled trial, 76 patients referred for mitral or tricuspid

TEER at Amsterdam UMC were randomized 1:1 to receive either standard verbal education (control) or

standard education plus a 7.5-minute immersive VR experience. Anxiety was measured using the State-

Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) immediately after

education and within one week prior to the procedure.

Results: Baseline analyses included 70 patients (mean age 77.9±7.3 years, 60% male); 50 completed

follow-up. Immediately after education, mean state anxiety scores were significantly lower in the VR

group compared to controls (37.7 vs. 41.9; p=0.04). However, state anxiety increased over time in the VR

group (+3.7 points; p=0.023), while the control group showed no significant change. At follow-up, anxiety

scores were similar between groups. Trait anxiety and HADS-A scores remained stable.

Conclusion: VR-based education acutely reduces state anxiety before TEER, but the effect is transient.

Optimal timing of VR interventions is essential to maximize benefit.

Keywords: Virtual reality; MitraClip; Triclip; Mitral valve regurgitation; Tricuspid valve regurgitation; Patient education

Abbreviations: EFS: Edmonton Frail Scale; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; M-TEER: Mitral Transcatheter Edge-To-Edge Repair; NYHA: New York Heart Association; S-STAI: State Anxiety; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety; T-TEER: Tricuspid Transcatheter Edge-To-Edge Repair; T-STAI: Trait Anxiety; TEER: Transcatheter Edge-To-Edge Repair; VR: Virtual Reality

Introduction

Pre-procedural anxiety is a significant concern for patients undergoing percutaneous cardiac interventions [1,2]. Anxiety is categorized into State Anxiety (S-STAI), which reflects situational emotional responses, and Trait Anxiety (T-STAI), a stable personality feature [3]. Preoperative anxiety has been linked to adverse outcomes such as increased anesthetic requirements, hemodynamic instability, elevated increased stress response, postprocedural nausea, vomiting, pain, insomnia, delayed recovery, extended hospital stays and long-term mortality [4,5]. However, its prevalence and impact in Transcatheter Edge-To-Edge Repair (TEER) remain unclear. Pharmacological interventions, such as benzodiazepines, have shown limited benefits in improving patient experience and are associated with delayed recovery [6]. Consequently, non-pharmacological approaches, particularly patient education, have gained attention. Virtual Reality (VR) has emerged as a promising tool for immersive patient education, with evidence suggesting its efficacy in reducing preoperative anxiety in elective surgeries [7,8], although in cardiology with mixed results [2,9]. This study aims to evaluate whether VR-based patient education can reduce pre-procedural anxiety in adults undergoing TEER procedures.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This single-center, prospective, randomized controlled pilot trial was conducted at Amsterdam UMC from October 2021 till December 2024. The primary aim was to assess the feasibility and preliminary effectiveness of immersive Virtual Reality (VR) education on pre-procedural anxiety in patients scheduled for Transcatheter Edge-To-Edge Repair (TEER). No formal sample size calculation was performed; a pragmatic target of at least 50 participants was set, consistent with previous feasibility studies [2]. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee, and all patients gave informed consent. The study was retrospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT07263659). Eligible participants were adults scheduled for elective mitral (M-TEER) or tricuspid (T-TEER) procedures. Exclusion criteria included insufficient Dutch proficiency, severe visual or auditory impairment, or any condition interfering with participation (e.g., cognitive decline, psychological distress, or inability to tolerate VR). Reasons for declining participation were systematically recorded.

Randomization and intervention

Participants were randomized 1:1 to either the VR intervention or control group, using a computer-generated sequence with block randomization stratified by procedure type. Outcome assessors and data analysts were blinded. The control group received standard verbal education from a nurse practitioner. The intervention group received the same education plus a 7.5-minute immersive VR experience (Oculus GO headset), including a virtual tour, 3D procedural visualization and messages from physicians. The VR video was filmed in the clinical environment with 360° techniques and spatial audio. Sessions took place after the outpatient consultation, with technical support provided. Patients could pause or stop the VR if needed, and adverse effects were documented. Afterward, patients received a secure YouTube link to rewatch the VR content at home; family members could also view the VR content. 360 degrees VR video M-TEER |360 degrees VR video T-TEER.

Control condition: Standard care education

The control group received standard procedural information per Amsterdam UMC protocol, delivered verbally by a nurse practitioner. No visual or immersive materials were used. Family members could attend, reflecting routine practice.

Outcome measures

Anxiety was measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The STAI Assesses State (S-STAI) and Trait (T-STAI) anxiety, with a cutoff of 40 for clinical anxiety [3]. The HADS-A subscale (range 0-21, cutoff ≥8) screens for clinical anxiety symptoms [10]. Questionnaires were completed after education (or VR exposure) and again within one week before the procedure.

Data management and handling of missing data

Data were collected in Castor EDC, pseudonymized, and securely stored. Only authorized personnel had access to identifiable data. Missing questionnaire data were not imputed; analyses were performed on complete cases. Reasons for missing data were recorded, and outliers were identified using a predefined IQR rule.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for baseline characteristics. Between-group comparisons used t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests; categorical variables used Chi-square tests. Within-group changes were assessed with paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Analyses were exploratory, with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. Analyses were performed in RStudio; p<0.05 was considered potentially meaningful for future research.

Results and Discussion

Patient characteristics

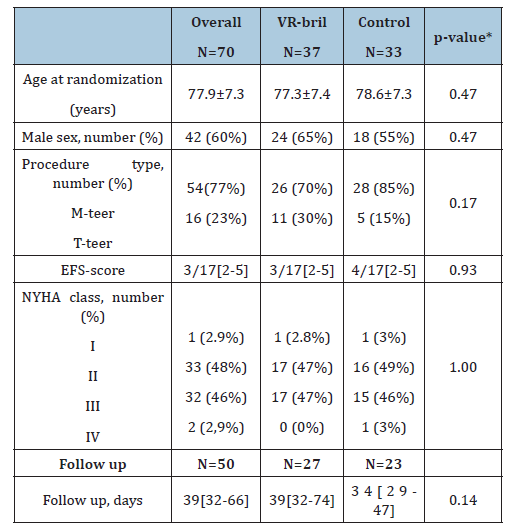

A total of 76 patients were randomized to either standard verbal education (control group) or verbal education supplemented by VR exposure (VR group). Of these, 70 participants completed the baseline assessment. For the follow-up analysis, 50 participants were included; 14 were excluded due to incomplete follow-up data and 6 were excluded based on predefined outlier criteria using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method (Figure 1). The mean age at randomization was 77.9±7.3 years, and 42 patients (60%) were male. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were well balanced between groups, suggesting successful randomization (Table 1).

Table 1:Baseline characteristics.

Data are mean ± standard deviation, median with Interquartile Range (IQR), n(%). EFS=Edmonton Frail Scale, FU=Follow-up (clinic visit–procedure), M-TEER=Mitral Transcatheter Edge-To-Edge Repair, NYHA=New York Heart Association, T-TEER=Tricuspid Transcatheter Edge- To-Edge Repair. *Group differences were tested with the t-test or with the Chi-square test.

Figure 1:CONSORT flow-chart.

Declined patients

A total of 79 patients (51%) declined participation in the study. 30 patients (38.5%) declined participation due to lack of interest in research, 22 patients (28.2%) due to no interest in additional information, 9 patients (11.5%) because of anxiety or psychological barriers, 10 patients (12.8%) because of discomfort with VR glasses, 5 patients (6.4%) because of health-related limitations, and 2 patients (2.6%) because of language barriers.

Anxiety Scores

Patients in the control group reported significantly higher S-STAI compared to those in the VR group (41.9±8.5 vs 37.7±7,7; p=0.04). There was no difference in T-STAI levels between control and VR group (35.4±8.0; =32.3±7.7; p=0.10). At follow-up, S-STAI scores were similar between control and VR group (mean 41.2±8.7 vs 40.9±8.9; p=0.88), S-STAI within the VR group was increased significantly when comparing the baseline score to the follow-up score (+3.70±7.9; p=0.023) while S-STAI remained unchanged in the control group (-1.04±6.54; p=0.45) (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Anxiety measures. Blue indicates control group, orange indicates VR group. Dot is the mean score, the error bars represent Standard Errors of the Mean (SEM). Asterisks (*) refer to statistically significant between-group differences or within-group changes (p<0.05), dotted line indicates clinical cutoff value of 40. Panel A shows the after clinic visit measures of the S-STAI, Panel B shows the measures over time of the S-STAI, Panel c shows the after clinic visit measures of the T-STAI, and Panel shows the measures over time of the T-STAI.

Next, anxiety symptoms using the HADS-A subscale were assessed. There was no difference in anxiety scores between the control group and the VR group measured by the HADS-A questionnaire at baseline (5.91±4.38 vs 3.81±2.65; p=0.053) or at follow up (3.91±3.99 vs 3.93±3.25; p=0.99).Satisfaction was high in both groups at baseline (Control: 8.9±0.9; VR: 9.2±0.6; p=0.30) and remained high at follow-up (Control: 8.1±1.3; VR: 8.5±0.9; p=0.23). Between-group differences in satisfaction were small and not statistically significant.

Discussion

This is the first study to assess VR-based patient education for reducing pre-procedural anxiety in TEER patients, representing an important advance in non-pharmacological anxiety management for this group. Our results show that VR education Significantly Lowers State Anxiety (S-STAI) immediately after exposure, bringing scores below the clinical cutoff of 40, while the control group’s anxiety remained unchanged and above 40. However, this reduction was temporary, anxiety in the VR group rose again by follow-up, exceeding the threshold, while the control group showed no significant change. This indicates that the timing of VR education is crucial, delivering it too early may reduce its benefit, as anxiety increases again before the procedure.

There were no differences in Trait Anxiety (T-STAI) or HADS-A scores, consistent with the idea that brief interventions do not affect stable personality traits. To maximize benefit, VR education should be given close to the procedure or repeated to maintain lower anxiety. Further research is needed to determine the best timing and frequency for VR interventions.

Limitations

This pilot study’s small sample size (70 patients) limits statistical power, so findings are mainly hypothesis-generating. Larger, multicenter studies are needed to evaluate long-term effects. Also, the absence of a true pre-intervention baseline limits conclusions about natural anxiety trends, and lack of long-term follow-up means the impact on recovery, satisfaction, and quality of life is unknown.

Conclusion

VR-based patient education is effective in acutely reducing state anxiety in patients undergoing TEER procedures. However, its anxiolytic effect is transient and therefore VR education should be delivered close to procedure. Further research is needed to refine the timing and integration of VR education into pre-procedural care.

Acknowledgements

M.H&B.B shaped the methodology of this study. M.H., E.C and L.V included patients, performed the randomizations, interventions, and outcome assessments. A.G and K.L performed the formal analysis of the data. A.G wrote the first draft of the paper. And, consequently, all authors reviewed the manuscript, after which final editing by A.G followed. B.B and J.B supervised the study and manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Delewi R, Vlastra W, Rohling WJ, Wagenaar TC, Zwemstra M, et al. (2017) Anxiety levels of patients undergoing coronary procedures in the catheterization laboratory. Int J Cardiol 228: 926-930.

- Pool MDO, Hooglugt JQ, Kraaijeveld AJ, Mulder BJM, de Winter RJ, et al. (2022) Pre-procedural virtual reality education reduces anxiety in patients undergoing atrial septal closure-results from a randomized trial. Int J Cardiol Congenit Heart Dis 7:100332.

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA (1983) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory, Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, USA.

- Ni K, Zhu J, Ma Z (2023) Preoperative anxiety and postoperative adverse events: A narrative overview. Anesthesiology and Perioperative Science 1(23).

- Ahmetovic-Djug J, Hasukic S, Djug H, Hasukic B, Jahic A (2017) Impact of preoperative anxiety in patients on hemodynamic changes and a dose of anesthetic during induction of anesthesia. Med Arch 71(5): 330-333.

- Euteneuer F, Kampmann S, Rienmuller S, Salzmann S, Rusch D (2022) Patients' desires for anxiolytic premedication-an observational study in adults undergoing elective surgery. BMC Psychiatry 22(1): 193.

- Guo P, East L, Arthur A (2012) A preoperative education intervention to reduce anxiety and improve recovery among Chinese cardiac patients: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 49(2): 129-137.

- Ramesh C, Nayak BS, Pai VB, Patil NT, George A, et al. (2017) Effect of preoperative education on postoperative outcomes among patients undergoing cardiac surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Perianesth Nurs 32(6): 518-529.e2.

- El Mathari S, Hoekman A, Kharbanda RK, Sadeghi AH, de Lind van Wijngaarden R, et al. (2024) Virtual reality for pain and anxiety management in cardiac surgery and interventional cardiology. JACC Adv 3(2): 100814.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6): 361-370.

© 2025 Berto J Bouma and Jan Baan. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)