- Submissions

Full Text

Open Journal of Cardiology & Heart Diseases

PCSK9 Inhibitors in Acute Coronary Syndrome: Mechanisms, Evidence and Clinical Application

Ashish Jha*, Sandeepan Saha and Bhuwan C Tiwari

Department of Cardiology, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Institute of Medical Sciences, India

*Corresponding author: Ashish Jha, Department of Cardiology, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Submission: October 06, 2025;Published: December 03, 2025

ISSN 2578-0204Volume5 Issue 2

Abstract

Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS) is associated with a high risk of recurrent cardiovascular events, particularly in the early post-event period, making aggressive lipid-lowering therapy a cornerstone of secondary prevention. Despite the established role of high-intensity statins, many patients fail to achieve recommended Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) targets, leaving significant residual risk. The aim of this review is to evaluate the mechanistic rationale, clinical evidence, and therapeutic role of PCSK9 inhibitors in Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS), with a focus on early initiation, plaquestabilizing effects, and their integration into contemporary secondary prevention strategies. Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, notably Alirocumab and Evolocumab, represent a transformative advance in lipid management. By preventing LDL receptor degradation, they lower LDL-C by 50-60% and lipoprotein(a) by 20-30%, while also exerting anti-inflammatory, antithrombotic, and plaque-stabilizing effects. Clinical trials such as FOURIER and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES have demonstrated significant reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events, with benefits most pronounced in patients with elevated baseline LDL-C. Emerging studies, including EVOPACS, EPIC-STEMI, and PACMAN-AMI, suggest that early or in-hospital initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors accelerates LDL-C reduction, enhances plaque stability, and may improve short-and long-term outcomes. International guidelines now recommend PCSK9 inhibitors for very-high-risk ACS patients, with European societies endorsing rapid escalation and stringent LDL-C targets, while American guidelines adopt a more stepwise approach.

Barriers to wider adoption include cost, access, and physician familiarity. Novel therapies such as Inclisiran, oral PCSK9 inhibitors, vaccines, and gene-editing technologies promise to improve adherence, accessibility, and long-term efficacy. In conclusion, PCSK9 inhibitors provide robust and multifaceted benefits in ACS, offering an effective strategy to reduce residual ischemic risk and reshape the landscape of secondary prevention.

Introduction to TTR Amyloidosis

Dyslipidemia, particularly elevated Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C), remains a cornerstone risk factor for the development and progression of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD). The relationship between LDL-C and cardiovascular risk is both causal and continuous, with landmark meta-analyses showing that each 1mmol/L reduction in LDL-C is associated with a 22% reduction in major vascular events, irrespective of baseline LDL-C levels or patient characteristics [1,2]. In the setting of Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS), aggressive lipid-lowering therapy is vital because patients are at high risk of recurrent cardiovascular events, especially in the first year following the index episode. Statins have long been the standard of care, providing both lipid-lowering and pleiotropic effects, yet a significant proportion of patients fail to achieve guideline-recommended LDL-C targets despite maximally tolerated statin therapy [3].

The advent of Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors represents a paradigm shift in lipid management. By preventing LDL receptor degradation, PCSK9 inhibitors-namely alirocumab and evolocumab-potently lower LDL-C by 50-60% on top of statins and ezetimibe, and also reduce lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] by 20-30% [4,5]. Clinical trials have demonstrated their efficacy not only in reducing LDL-C but also in improving plaque morphology, stabilizing vulnerable lesions, and reducing Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) [6-8]. Guidelines now advocate for the use of PCSK9 inhibitors in very-high- risk patients, particularly those with ACS who do not achieve target LDL-C levels with statins and ezetimibe. The 2025 ESC guidelines recommend an LDL-C reduction of ≥50% from baseline and a goal of <55mg/dL (<1.4mmol/L) for patients with ACS, with even more stringent targets (<40mg/dL or <1.0mmol/L) in those experiencing recurrent events within two years [9]. The ACC/AHA guidelines similarly endorse PCSK9 inhibitors for patients with LDL-C ≥70mg/ dL despite maximal statin and ezetimibe therapy [10].

Emerging data suggest that the timing of initiation-particularly during hospitalization for ACS-may be critical. Early introduction of PCSK9 inhibitors may provide faster plaque stabilization, optimize LDL-C reduction when residual risk is highest, and improve longterm outcomes. This chapter will explore the mechanistic rationale, trial evidence, clinical applications, and emerging therapies in the context of PCSK9 inhibition during ACS.

Pathophysiological Basis of PCSK9 Inhibition in ACS

PCSK9 biology and LDL receptor regulation

PCSK9 is a serine protease primarily synthesized in hepatocytes that plays a pivotal role in cholesterol homeostasis. It binds to LDL Receptors (LDLR) on hepatocyte surfaces, targeting them for lysosomal degradation rather than recycling to the cell surface [11]. Elevated PCSK9 levels reduce LDLR availability, impair LDL-C clearance, and increase circulating LDL-C concentrations.

PCSK9 expression is upregulated by Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Proteins (SREBPs), especially during states of increased cholesterol demand or inflammation [12]. Importantly, patients with gain-of-function mutations in PCSK9 exhibit familial hypercholesterolemia and accelerated ASCVD, whereas loss-offunction mutations confer lifelong reductions in LDL-C and up to 88% lower risk of coronary heart disease [13].

PCSK9 in acute coronary syndromes

The role of PCSK9 extends beyond lipid metabolism. ACS is characterized by heightened systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction, all of which influence PCSK9 levels. Studies show that plasma PCSK9 levels are acutely elevated in ACS patients and correlate with poor outcomes, suggesting that PCSK9 itself may be a biomarker of risk [14].

PCSK9 may promote atherogenesis and plaque instability by

mechanisms independent of LDL-C:

A. Inflammatory modulation: PCSK9 upregulates proinflammatory

cytokines via toll-like receptor pathways [15].

B. Platelet activation: It enhances platelet aggregation by

binding to CD36, linking PCSK9 to thrombotic risk [16].

C. Endothelial dysfunction: PCSK9 impairs nitric oxide

bioavailability and promotes oxidative stress [17].

D. Lipoprotein(a) regulation: PCSK9 inhibition reduces

Lp(a), which is highly pro-atherogenic and thrombogenic [18].

Thus, PCSK9 inhibitors provide multifaceted benefits in ACS patients by reducing LDL-C and Lp(a) while potentially attenuating inflammation, thrombosis, and plaque vulnerability.

Effects on plaque biology

Intravascular imaging studies have consistently shown that

greater LDL-C lowering is associated with more pronounced plaque

regression and stabilization. By achieving ultra-low LDL-C levels

(<30mg/dL), PCSK9 inhibitors facilitate:

a. Increase in fibrous cap thickness, enhancing stability

against rupture.

b. Reduction in lipid core burden, decreasing vulnerability

to thrombosis.

c. Decreased macrophage infiltration, reflecting reduced

inflammation within the plaque [6,7].

Collectively, these mechanisms form the pathophysiological rationale for initiating PCSK9 inhibitors early in ACS to mitigate residual ischemic risk.

Guideline Recommendations for PCSK9 Inhibitors in ACS

International guidelines uniformly emphasize aggressive lipid lowering as a fundamental strategy in secondary prevention following ACS, yet there are important regional differences in how and when PCSK9 inhibitors are recommended.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in its most recent guidelines on acute coronary syndromes and dyslipidemia management, advocates for intensive LDL-C lowering in all patients following ACS. The targets are ambitious: a reduction of at least 50% from baseline levels and an absolute goal of <55mg/ dL (1.4mmol/L). For patients considered at ultra-high risk, such as those experiencing a recurrent coronary event within two years, the LDL-C target is set even lower, at <40mg/dL (1.0mmol/L). The guidelines recommend initiating high-intensity statins immediately and then rapidly intensifying therapy with ezetimibe and a PCSK9 inhibitor if LDL-C remains above goal. Importantly, they acknowledge the potential role of early or even in-hospital initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors in ACS patients at highest risk, reflecting the recognition that residual risk is greatest in the immediate postevent period [9,19]. In contrast, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) have taken a more stepwise approach. Their cholesterol guidelines recommend PCSK9 inhibitors for very-high-risk patients-including those with recent ACS-only if LDL-C remains ≥70mg/dL despite maximally tolerated statin and ezetimibe therapy. While this threshold is higher than that advocated by the ESC, there is growing recognition in North America that earlier initiation may be advantageous, especially as real-world data confirm both safety and clinical efficacy [20].

Other societies, such as the Canadian Cardiovascular Society and the National Lipid Association, have broadly aligned with the ESC recommendations. These groups support earlier consideration of PCSK9 inhibitors in patients with ACS and emphasize their use in patients with markedly elevated LDL-C, familial hypercholesterolemia, or elevated lipoprotein(a). Taken together, there is a clear movement across guidelines toward acknowledging the value of PCSK9 inhibition in ACS, though practical considerations such as drug availability and healthcare system economics continue to shape adoption.

Indian patients tend to develop ASCVD at younger ages and at lower LDL-C levels compared to Western populations. The Lipid Association of India (LAI) recommends intensive LDL-C reduction, with targets of <50mg/dL for very high-risk patients and as low as ≤30mg/dL for those in the extreme-risk category, such as individuals with established ASCVD plus diabetes with organ damage or recurrent cardiovascular events. The overarching aim is to minimize major adverse cardiovascular events by pursuing aggressive lipid-lowering strategies, supported by a thorough discussion of risks and benefits before initiating therapy [21].

Clinical Trial Evidence for PCSK9 Inhibitors in ACS

The evidence base supporting PCSK9 inhibitors in ACS comes from both large outcome trials and smaller mechanistic or imaging studies. Together, they provide a compelling case for the efficacy and safety of these agents across the continuum of ACS management.

The FOURIER trial was the first large-scale outcomes study of evolocumab in patients with established atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, many of whom had a history of ACS. Over a median follow-up of 2.2 years, evolocumab reduced LDL-C by 59% to a median of 30mg/dL and produced a 15% relative risk reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events. Importantly, the benefit was proportional to the degree of LDL-C reduction, reinforcing the “lower is better” paradigm. Subgroup analyses suggested consistent efficacy in patients with recent myocardial infarction, supporting the relevance of PCSK9 inhibition in the ACS population [5].

The ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial specifically evaluated alirocumab in patients 1 to 12 months after an ACS event. Over 18,000 patients were randomized, and after a median follow-up of 2.8 years, alirocumab reduced the risk of recurrent ischemic events by 15%. Interestingly, the absolute benefit was greatest in patients with baseline LDL-C ≥100mg/dL, highlighting the particular value of PCSK9 inhibition in those with more severe dyslipidemia or residual risk. Beyond reducing recurrent events, alirocumab also demonstrated a mortality benefit in patients with elevated baseline LDL-C, an observation not seen in many prior lipid-lowering trials [8]. Beyond these landmark studies, a series of smaller but informative trials have explored the role of early initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors during the index hospitalization for ACS. The EVOPACS trial demonstrated that starting evolocumab within the first days of hospitalization led to an additional 40% reduction in LDL-C on top of statin therapy, with more than 95% of patients achieving guideline-recommended LDL-C targets within eight weeks [22]. Similarly, the EPIC-STEMI study tested alirocumab administration at the time of primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Results showed rapid LDL-C reduction within 24-48 hours, suggesting that ultra-early therapy may influence the vulnerable thrombotic milieu of ACS [23].

Perhaps most compelling are the insights from intracoronary imaging studies. The PACMAN-AMI trial evaluated evolocumab in ACS patients using multimodality imaging, including intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography, and near-infrared spectroscopy. Over 52 weeks, patients treated with evolocumab showed significant regression in plaque burden, thickening of the fibrous cap, and a reduction in lipid content-hallmarks of improved plaque stability. These findings provide biological plausibility for the clinical benefits observed in large outcome trials and highlight the unique potential of PCSK9 inhibitors to favorably modify plaque characteristics beyond LDL-C lowering alone [7]. Another important dimension of PCSK9 inhibitors in ACS is their ability to reduce lipoprotein(a) levels by approximately 20-30% [4,5]. Elevated Lp(a) is increasingly recognized as an important driver of residual risk in ACS, and no other currently available lipid-lowering agent has demonstrated such consistent Lp(a)-lowering effects. This makes PCSK9 inhibition particularly attractive in patients with elevated Lp(a), a subgroup for whom therapeutic options remains limited..

Safety has been a recurring concern with the pursuit of ultra-low LDL-C levels. However, across FOURIER, ODYSSEY, and subsequent extension studies, PCSK9 inhibitors have proven remarkably safe and well tolerated. No excess neurocognitive adverse events, no signal for new-onset diabetes, and only minimal rates of injectionsite reactions have been observed. Long-term follow-up extending to nearly five years confirms both efficacy and safety, providing reassurance about the chronic use of these therapies in secondary prevention.

In sum, the collective trial evidence demonstrates that PCSK9 inhibitors, when added to standard therapy in ACS patients, deliver profound LDL-C reduction, lower the risk of recurrent ischemic events, favorably influence plaque biology, and offer additional benefit in lowering lipoprotein(a). The challenge moving forward is not whether they work, but rather how best to integrate them into practice in a way that maximizes patient benefit while navigating cost and access barriers.

Clinical Applications of PCSK9 Inhibitors in ACS

The translation of mechanistic and trial evidence into realworld practice requires careful consideration of who to treat, when to start therapy, and how to incorporate PCSK9 inhibitors into existing lipid-lowering regimens. In patients presenting with ACS, the principle of “the lower, the earlier, the better” has gained wide acceptance, reflecting the vulnerability of this period when the risk of recurrent ischemic events is greatest.

Patient selection

Not every patient admitted with an acute coronary syndrome requires PCSK9 inhibition, but specific subgroups derive substantial benefit. Patients at very high risk-such as those with recurrent ACS within a short span of time, those with extensive multivessel coronary artery disease, or those with coexisting conditions such as diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, or peripheral artery disease-represent ideal candidates. Furthermore, patients with familial hypercholesterolemia who experience ACS constitute a group where early and aggressive lipid lowering is essential, since achieving LDL-C targets with conventional agents is often unrealistic. Another important category includes patients with elevated lipoprotein(a), a powerful and independent determinant of residual cardiovascular risk, where PCSK9 inhibitors offer the added advantage of lowering Lp(a) levels in addition to LDL-C [24].

Timing of initiation

The question of when to initiate PCSK9 inhibition in ACS has evolved considerably. Traditional practice has been to adopt a sequential “stepwise” approach: initiating high-intensity statin therapy first, reassessing LDL-C levels after 4-6 weeks, and adding ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors only if targets were not achieved [10]. While pragmatic, this strategy exposes patients to several weeks or months of suboptimal LDL-C lowering during the period of highest vulnerability to recurrent events. More recent evidence supports an alternative approach-early, even in-hospital initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors. The EVOPACS and EPIC-STEMI trials demonstrated that adding evolocumab or alirocumab within the first days of ACS hospitalization leads to rapid and profound LDL-C reductions, with most patients achieving guideline targets within weeks rather than months [22,23]. The PACMAN-AMI study further highlighted the biological benefits of early therapy by demonstrating favorable changes in plaque characteristics, including reductions in lipid content and increases in fibrous cap thickness [7]. These findings collectively argue in favour of early initiation of PCSK9 inhibitors during or immediately after hospitalization for ACS, particularly in patients with very high-risk features.

Integration with other lipid-lowering therapies

PCSK9 inhibitors are best viewed not as replacements, but as complementary agents to statins and ezetimibe. In fact, the greatest efficacy in achieving LDL-C goals is seen with triple therapy comprising a high-intensity statin, ezetimibe, and a PCSK9 inhibitor. Such a combination routinely enables more than 80% of ACS patients to meet the stringent ESC-recommended LDL-C target of <55mg/dL [19]. In patient’s intolerant to statins, PCSK9 inhibitors can be combined with ezetimibe as an alternative regimen, though evidence in statin-intolerant ACS populations remains more limited [25].

Special considerations in distinct patient populations

Elderly patients, who often present with ACS and multiple comorbidities, have shown comparable benefit from PCSK9 inhibitors as younger populations, with no increase in adverse effects. Similarly, diabetic patients-who constitute a substantial proportion of ACS cases-experience significant reductions in cardiovascular events with PCSK9 therapy, with some exploratory data even hinting at microvascular benefit [26]. Patients with moderate chronic kidney disease also respond well to PCSK9 inhibition, though data remain sparse in advanced kidney disease and dialysis. Another subgroup where these agents appear particularly valuable are post-CABG patients presenting with ACS, where aggressive lipid lowering is critical to maintaining graft patency and reducing subsequent ischemic events [27].

Practical challenges and real-world use

Despite compelling trial evidence, several practical barriers limit the widespread uptake of PCSK9 inhibitors in ACS. Cost remains the most significant challenge, although recent price reductions and increasing recognition of their cost-effectiveness in veryhigh- risk populations are gradually improving access. Real-world registries suggest that utilization rates are still low compared with guideline recommendations, reflecting not only financial hurdles but also issues of physician familiarity, administrative complexity, and patient reluctance toward injectable therapies. Education and training on self-administration can mitigate adherence challenges, and real-world studies indicate high persistence once therapy is initiated. Importantly, long-term safety data from extension trials extending up to five years provide reassurance about their tolerability, with no unexpected adverse events observed.

Emerging therapies and future directions

Although monoclonal antibody-based PCSK9 inhibitors have transformed lipid management, their requirement for frequent subcutaneous injections and high-cost limit widespread adoption, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where the burden of ACS is disproportionately high. As a result, considerable effort has been devoted to developing novel approaches that target PCSK9 with greater convenience, durability, and potentially improved cost-effectiveness.

RNA-targeted therapies

Inclisiran, a Small Interfering RNA (siRNA) therapy, represents the most advanced alternative to monoclonal antibodies. Unlike alirocumab or evolocumab, which neutralize circulating PCSK9 protein, inclisiran acts intracellularly by silencing PCSK9 messenger RNA within hepatocytes, thereby reducing PCSK9 synthesis at its source. Administered as a subcutaneous injection on day 0, at three months, and then every six months, inclisiran offers the advantage of twice-yearly dosing. This simplified regimen addresses a key limitation of monoclonal antibodies-treatment adherence.

Clinical trials, including the ORION program, have shown that inclisiran lowers LDL-C by approximately 50% on top of statin therapy, with durable effects lasting between dosing intervals. Importantly, inclisiran has been well tolerated, with injectionsite reactions being the most common adverse event [28]. While cardiovascular outcome data are still pending, pooled analyses suggest fewer cardiovascular events among inclisiran-treated patients, raising optimism that its benefits will parallel those seen with antibody-based therapies. Large ongoing outcome trials, such as VICTORION-2 PREVENT, are expected to clarify its role in ACS management [29].

Oral PCSK9 inhibitors

Another promising frontier is the development of oral smallmolecule inhibitors of PCSK9. Early-phase studies with a tricyclic macrocyclic compound have shown bioavailability sufficient to reduce circulating PCSK9 by 90% and LDL-C by up to 65% [30]. If confirmed in larger trials, an oral formulation would represent a paradigm shift, offering patients the familiarity and convenience of daily tablets while maintaining the profound LDL-C reductions observed with injectable therapies. Such an advance would be particularly valuable in resource-constrained settings, where injectable biologics pose logistical and financial barriers.

Vaccine-based approaches

An innovative strategy currently in preclinical development is the use of PCSK9-targeted vaccines [31]. These vaccines aim to induce a sustained immune response against PCSK9, generating long-lasting antibody production that reduces circulating PCSK9 activity. Preclinical animal studies have demonstrated reductions in LDL-C of more than 40% with durable effects lasting months to years after a single administration. If successfully translated to humans, PCSK9 vaccination could provide long-term lipid control with dosing intervals as infrequent as once a year-or even once in a lifetime. However, major questions remain regarding the durability of immune responses, potential for autoimmunity, and reversibility in the event of adverse effects.

Gene editing and CRISPR technologies

The most futuristic and potentially transformative approach to PCSK9 inhibition is gene editing. Using CRISPR-based techniques, researchers have demonstrated in non-human primates that permanent disruption of the PCSK9 gene results in sustained LDL-C reduction of more than 50% [32]. This “one-and-done” strategy holds the promise of lifelong LDL-C lowering from a single treatment. If proven safe and effective in humans, gene editing could fundamentally alter the management of dyslipidemia, especially in patients with familial hypercholesterolemia or recurrent ACS who require aggressive lipid-lowering throughout life. Still, ethical, safety, and long-term monitoring challenges must be carefully addressed before gene-editing strategies can enter clinical practice.

Ongoing and Upcoming Clinical Trials

Several ongoing randomized trials are expected to further

define the role of PCSK9 inhibition in ACS, particularly in the early

post-event period, where residual risk is highest.

A. EVOLVE-MI (NCT05284747): A large-scale trial enrolling

4,000 patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction,

testing whether evolocumab added to standard care reduces

cardiovascular events compared with placebo.

B. VICTORION-INCEPTION (NCT04873934): Evaluating

inclisiran in post-ACS patients with persistently high LDL-C

levels despite statin therapy, with a focus on long-term

outcomes and adherence advantages.

C. AMUNDSEN (NCT04951856): Testing evolocumab

administered before PCI in ACS patients, aiming to assess

not only lipid lowering but also whether ultra-early therapy

influences ischemic outcomes and vascular healing.

D. SPECIAL trial: Currently assessing evolocumab in patients

with non-ST elevation ACS and non-culprit critical lesions, with

an emphasis on safety and progression of atherosclerosis.

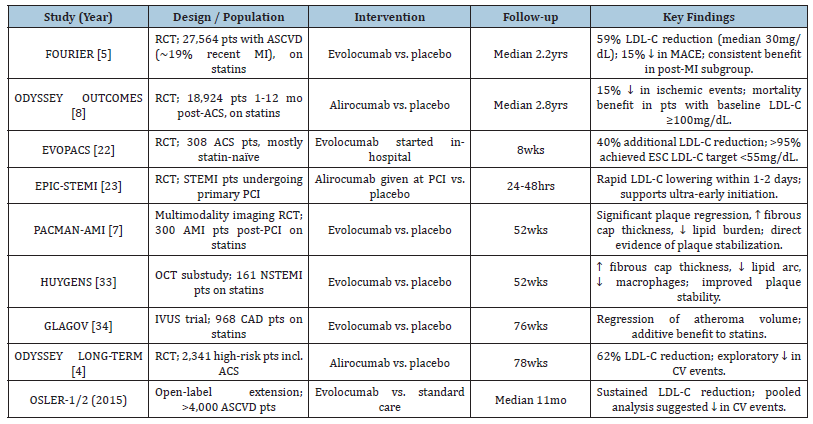

The results of these trials are eagerly awaited, as they will refine not only the timing of PCSK9 initiation but also provide clarity on their impact in the acute phase of ACS, a setting where rapid risk reduction is critically needed. A Summary of Key Clinical Studies of PCSK9 Inhibitors in ACS is illustrated in table [4,33,34] (Table 1).

Table 1:Summary of key clinical studies of PCSK9 inhibitors in ACS.

Conclusion

PCSK9 inhibitors have transformed lipid management in acute coronary syndromes, achieving rapid and substantial LDL-C reduction beyond that attainable with statins and ezetimibe. Landmark trials such as FOURIER and ODYSSEY OUTCOMES demonstrated significant reductions in recurrent ischemic events, supporting their role in secondary prevention, particularly for very-high-risk patients. Beyond lipid lowering, PCSK9 inhibitors reduce lipoprotein(a), enhance plaque stability, and may exert anti-inflammatory effects, addressing key components of residual cardiovascular risk. Despite robust evidence, their widespread adoption is limited by high cost, access constraints, and limited familiarity among clinicians. Emerging agents-including inclisiran, oral PCSK9 inhibitors, vaccines, and gene-editing therapies-offer promise for improved adherence, affordability, and durability of lipid control.

In summary, PCSK9 inhibitors represent a major advance in ACS management and, with evolving innovations, are poised to become an integral component of precision secondary prevention in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

References

- Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Holland LE, Reith C, et al. (2010) Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: A meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 376(9753): 1670-1681.

- Fulcher J, O’Connell R, Voysey M, Emberson J, Blackwell L, et al. (2015) Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: Meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet 385(9976): 1397-1405.

- Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, et al. (2015) Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 372(25): 2387-2397.

- Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, Bergeron J, Luc G, et al. (2015) Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 372(16): 1489-1499.

- Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, et al. (2017) Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 376(18): 1713-1722.

- Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson T, Ballantyne CM, Cho L, et al. (2016) Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: The GLAGOV randomized clinical trial JAMA 316(22): 2373-2384.

- Räber L, Ueki Y, Otsuka T, Losdat S, Häner JD, et al. (2022) Effect of alirocumab added to high-intensity statin therapy on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction: The PACMAN-AMI randomized clinical trial. JAMA 327(18): 1771-1781.

- Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, Bhatt DL, Bittner VA, et al. (2018) Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 379(22): 2097-2107.

- Mach F, Koskinas KC, Roeters van Lennep JE, Tokgözoğlu L, Badimon L, et al. (2025) 2025 Focused Update of the 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Developed by the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). European Heart Journal 46(42): 4359-4378.

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, et al. (2019) 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: Executive summary: A report of the american college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 73(24): 3168-3209.

- Seidah NG, Awan Z, Chrétien M, Mbikay M (2014) PCSK9: A key modulator of cardiovascular health. Circ Res 114(6): 1022-1036.

- Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH (2007) Molecular biology of PCSK9: Its role in LDL metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci 32(2): 71-77.

- Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabès JP, Allard D, Ouguerram K, et al. (2003) Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet 34(2): 154-156.

- Cui CJ, Li S, Zhu CG (2017) Plasma PCSK9 levels and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circ Res 120(10): 1661-1669.

- Tang Z, Jiang L, Peng J, Ren Z, Wei D, et al. (2012) PCSK9 siRNA suppresses the inflammatory response induced by ox-LDL through inhibition of NF-κB activation in THP-1-derived macrophages. Int J Mol Med 30(4): 931-938.

- Qi Z, Hu L, Zhang J, Yang W, Liu X, et al. (2021) PCSK9 (Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin 9) enhances platelet activation, thrombosis, and myocardial infarct expansion by binding to platelet CD36. Circulation 143(1): 45-61.

- Ding Z, Liu S, Wang X, Theus S, Deng X, et al. (2018) PCSK9 regulates expression of scavenger receptors and ox-LDL uptake in macrophages. Cardiovasc Res 114(8): 1145-1153.

- Tavori H, Giunzioni I, Linton MF, Fazio S (2016) Loss of plasma Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/Kexin 9 (PCSK9) increases lipoprotein(a) levels in experimental models and in humans. Circulation 133(10): 1030-1039.

- Mach F, Baigent C, Catapano AL, Koskinas KC, Casula M, et al. (2020) 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: Lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 41(1): 111-188.

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, Birtcher KK, Covington AM, et al. (2022) 2022 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of nonstatin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: A report of the American college of cardiology solution set oversight committee. J Am Coll Cardiol 80(14): 1366-1418.

- Puri R, Bansal M, Mehta V, Duell PB, Wong ND, et al. (2024) Lipid association of India 2023 update on cardiovascular risk assessment and lipid management in Indian patients: Consensus statement IV. Journal of clinical lipidology 18(3): e351-e373.

- Koskinas KC, Räber L, Zanchin T (2020) Effect of early, intensive lipid-lowering therapy with evolocumab on coronary plaque phenotype in patients with acute coronary syndromes (EVOPACS). Eur Heart J 41(40): 3892-3901.

- Mehta SR, Pare G, Lonn EM, Jolly SS, Natarajan MK, et al. (2022) Effects of routine early treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: A randomised, double-blind, sham-controlled trial. EuroIntervention 18(11): e888-e896.

- Tavori H, Giunzioni I, Linton MF, Fazio S (2016) PCSK9 inhibition reduces Lp(a) levels: Mechanisms and implications. Circulation 133(10): 1030-1039.

- Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M (2015) Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in statin-intolerant patients. Lancet 385(9985): 2200-2211.

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA, et al. (2019) Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med 380(1): 11-22.

- Nasso G (2021) Early PCSK9 inhibition post-CABG in ACS: Safety and efficacy. J Cardiovasc Surg 62(4): 344-352.

- Ray KK, Wright RS, Kallend D (2020) Two-year efficacy and safety of inclisiran in high cardiovascular risk patients. N Engl J Med 382: 1507-1519.

- (2020) A study of inclisiran to prevent Cardiovascular (CV) events in participants with established cardiovascular disease (VICTORION-2P). National Institutes of Health, Maryland, USA.

- Ridker PM (2021) Early-phase trials of oral PCSK9 inhibitors: Efficacy and safety. J Am Coll Cardiol 78: 123-134.

- Kaczmarek JC (2020) Preclinical development of PCSK9 vaccines using nanoliposome delivery. Circulation 141: 1234-1246.

- Musunuru K, Chadwick AC, Mizoguchi T, Garcia SP, DeNizio JE, et al. (2021) In vivo CRISPR base editing of PCSK9 durably lowers cholesterol in primates. Nature 593(7859): 429-434.

- Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson T, Ballantyne CM, Cho L, et al. (2022) Effect of evolocumab on coronary plaque phenotype and burden in statin-treated patients following myocardial infarction: The HUYGENS study. Circulation 146(16): 1173-1184.

- Nicholls SJ, Puri R, Anderson T, Ballantyne CM, Cho L, et al (2016) Effect of evolocumab on progression of coronary disease in statin-treated patients: The GLAGOV randomized clinical trial. JAMA 316(22): 2373-2384.

© 2025 Ashish Jha. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)