- Submissions

Full Text

Open Journal of Cardiology & Heart Diseases

The Evolving Role of Sodium-Glucose Linked Transporter-2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors in Heart Failure Management: A Paradigm Shift

Moses Adondua Abah1*, Micheal Abimbola Oladosu2, Odusanya Kikunlore Elijah3, Ezeudu Paschal Chikelum4, Ayoade Babatunde Olanrewaju5, Aishat Temitope Alonge6, Ekpenyong Utomobong Sunday7, Ochuele Dominic Agida1, Okwah Micah Nnabuko8 and Omolere Femi9

1Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biosciences, Federal University Wukari, Nigeria

2Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, University of Lagos, Nigeria

3Department of Hematology and Blood Transfusion, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

4Medicine and Surgery Department, Faculty of Clinical Sciences, University of Lagos, Nigeria

5Biology and Environmental Science Department, College of Arts and Sciences, University of New Haven, USA

6Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria

7College of Medicine, University of Uyo Teaching Hospital, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria

8Department of Chronic Disease Epidemiology, Yale University, Connecticut, USA

9Department of Pharmacy, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital, Calabar, Cross River State, Nigeria

*Corresponding author: Moses Adondua Abah, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biosciences, Federal University Wukari, Nigeria

Submission: September 12, 2025;Published: November 21, 2025

ISSN 2578-0204Volume5 Issue 1

Abstract

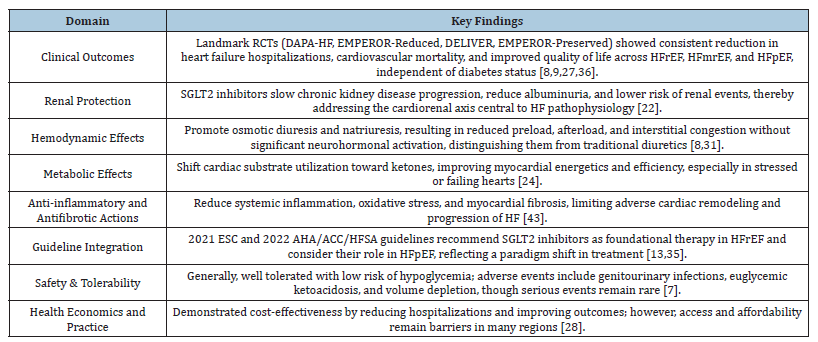

Despite advancements in conventional therapies like β-blockers, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, Heart Failure (HF) continues to be a global health concern that contributes significantly to morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs. There is a pressing need for innovative therapeutic approaches since, despite their effectiveness in many situations, these medications frequently fall short of adequately addressing the intricate pathophysiology of HF. Originally created to help control blood sugar levels in people with type 2 diabetes, Sodium-Glucose Linked Transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have lately shown impressive cardiovascular and renal advantages that go beyond its ability to lower blood sugar levels. Regardless of diabetes status, landmark clinical trials including DAPA-HF, EMPEROR-Reduced, EMPEROR-Preserved, and DELIVER have continuously demonstrated improvements in symptoms, a decrease in hospitalization rates, and a reduction in mortality across a wide range of HF phenotypes. Due to these results, SGLT2 inhibitors have been quickly included in international HF management recommendations, establishing them as a cornerstone treatment in addition to well-known medications. However, there are also issues, such as worries about side effects, cost-effectiveness, practical adherence, and evidence gaps in underrepresented and advanced heart failure patients. With an emphasis on their pharmacological characteristics, molecular insights, clinical evidence, and recommended guidelines, this review explored the changing role of SGLT2 inhibitors in the treatment of heart failure. It also looked at current studies, potential treatment paths, and the wider effects of this paradigm change on clinical practice and cardiovascular health. Findings from this study revealed that SGLT2 inhibitors have shown significant cardiovascular benefits in heart failure management, reducing hospitalizations and mortality. These agents improve cardiac function, reduce inflammation and oxidative stress, and enhance diuresis. Clinical trials demonstrate their efficacy in patients with and without diabetes, shifting the paradigm in heart failure treatment. In conclusion, SGLT2 inhibitors represent a groundbreaking therapeutic approach in heart failure management, offering new hope for improved patient outcomes and reduced healthcare burden.

Keywords:SGLT2 inhibitors; Heart failure; Therapies; Inflammation; Oxidative stress

Introduction to TTR Amyloidosis

Globally, Heart Failure (HF) continues to be a major cause of morbidity and mortality, putting a significant strain on healthcare systems. Over 55 million people worldwide currently have Heart Failure (HF), and prevalence rates are rising as a result of aging populations and better survival after acute cardiac events such myocardial infarction [1]. About 6.7 million individuals in the US alone are impacted, and estimates indicate that almost 15 million more are at increased risk over the course of the next ten years [2]. The mortality rate is still very high; according to recent data from Sweden, one in four newly diagnosed heart failure patients passed away within the first year, underscoring the need for care regimens to be optimized [3]. HF is one of the most urgent global health issues because, in addition to death, it significantly lowers quality of life through repeated hospitalizations, exercise intolerance, and progressive multi-organ failure.

In order to address maladaptive activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS), traditional HF treatment has mostly focused on neurohormonal regulation. According to Butler et al. [4], the cornerstone of treatment has traditionally consisted of medications like ACE Inhibitors (ACEi), Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs), β-blockers, and Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs), which have been shown to dramatically improve outcomes for patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF). With their dual RAAS inhibition and natriuretic peptide augmentation, Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitors (ARNIs) have lately broadened the treatment arsenal and shown additional benefits [5]. There are still significant therapeutic gaps in spite of these advancements. Crucially, patients with Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF), who currently account for about half of all HF cases, have seen little to no mortality benefit from this traditional therapy. Hospitalizations and death rates are still high [4]. The need for new drugs with mechanisms other than neurohormonal inhibition is highlighted by this therapeutic gap.

In light of this, Sodium-Glucose Linked Transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors first appeared as antidiabetic medications but quickly showed impressive cardiovascular advantages that went beyond glycemic control. These medications cause osmotic diuresis and natriuresis by blocking the reabsorption of glucose and sodium, mainly in the proximal renal tubule. Regardless of participants’ preexisting heart failure status, early cardiovascular outcome trials in diabetes, like EMPA-REG OUTCOME and CANVAS, unexpectedly showed significant decreases in heart failure hospitalization [6,7]. In both diabetic and non-diabetic groups, this led to specific HF trials. Dapagliflozin, regardless of diabetes status, decreased the composite endpoint of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death by 26% in patients with HFrEF, according to the DAPA-HF study [5]. Similarly, empagliflozin was found to reduce relative risk by 25% in HFrEF, according to the EMPEROR-Reduced study [8]. The findings in HFpEF, where the DELIVER and EMPEROR-Preserved trials showed clinically significant decreases in HF hospitalization, were even more revolutionary. This was the first time that pharmacological therapy provided significant benefits across the whole spectrum of EF [9]. Together, these results established SGLT2 inhibitors as a ground-breaking class of medications in the field of cardiology.

These findings have significant ramifications. Due to several treatment failures, HFpEF was considered “the graveyard of clinical trials” and cardiologists had few alternatives for decades [10]. In addition to challenging established paradigms, the consistent effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitors across HFrEF, HFmrEF, and HFpEF points to a fundamental change in the way HF is understood and treated. Their advantages go beyond hemodynamic unloading; they also target several pathways linked to the pathophysiology of HF by improving myocardial energetics, protecting the kidneys, reducing systemic inflammation, and having antifibrotic effects [4,11]. Their function as disease-modifying drugs rather than symptomatic remedies is reinforced by these pleiotropic effects. Accordingly, SGLT2 inhibitors are currently advised as the first line of treatment for all HF patients with symptoms, regardless of whether they have diabetes, according to recent international guidelines, such as the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA and 2023 ESC updates [12].

This review aimed at thoroughly investigating the changing function of SGLT2 inhibitors in the treatment of heart failure. Specifically, it examined the pharmacology and mechanisms by which SGLT2 inhibitors exert cardiovascular and renal benefits, critically evaluate the evidence from landmark clinical trials across the spectrum of heart failure, contextualize the global burden of heart failure and the limitations of conventional therapies, and discuss integration into clinical practice, guidelines, challenges, and future research directions. With ramifications for patients, physicians, and healthcare systems around the world, the review demonstrates how SGLT2 inhibitors constitute a paradigm shift in the treatment of HF rather than only a little improvement.

Pathophysiology of heart failure and the therapeutic gap

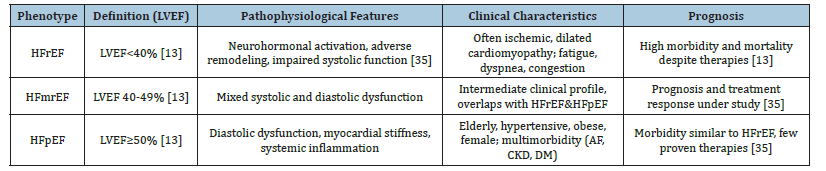

The anatomical and functional deterioration of ventricular filling or blood ejection causes Heart Failure (HF), a diverse clinical condition. According to the Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF), it is classified clinically into three phenotypes: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF, LVEF≥50%), heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF, LVEF<40%), and heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction (HFmrEF, LVEF 40-49%) [13]. Every phenotype represents different but overlapping pathophysiological processes. Whereas HFpEF frequently entails diastolic failure, systemic inflammation, and vascular stiffness, HFrEF is usually linked to systolic dysfunction and ventricular remodeling after ischemia or non-ischemic injury [14]. An intermediate entity known as HFmrEF has surfaced; it may be a transitory condition and shares traits with both HFrEF and HFpEF. Since they direct treatment plans and provide prognostic information, these classifications are therapeutically significant [15].

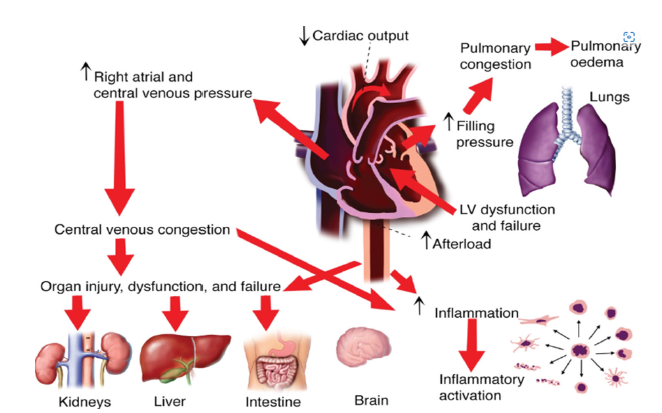

Neurohormonal activation, specifically the elevation of the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) and Renin-Angiotensin- Aldosterone System (RAAS), is a major factor in the progression of heart failure regardless of phenotype. Vasoconstriction, water and sodium retention, and a rise in afterload are the results of persistent activation, which at first makes up for decreased cardiac output but eventually speeds up maladaptive ventricular remodeling [16]. Myocardial hypertrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and chamber dilatation are characteristics of this remodeling that prolong diastolic and systolic dysfunction. Moreover, endothelial dysfunction and multi-organ involvement, including the kidneys and skeletal muscle, are caused by inappropriate activation of the natriuretic peptide system, increased oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation. These interrelated processes highlight the fact that HF is a complicated systemic illness rather than just a cardiac condition [17] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 above shows how the systolic and diastolic dysfunction trigger neurohormonal activation, including the sympathetic nervous system and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, promoting vasoconstriction and fluid retention. Ventricular remodeling occurs through hypertrophy and dilation, further impairing cardiac function. Inflammation and oxidative stress exacerbate damage, while peripheral changes like vascular dysfunction and fluid overload worsen symptoms. Organ dysfunction, including kidney and pulmonary congestion, can develop.

Figure 1:Pathophysiology of heart failure. Source: Ranek et al. [17].

ACE inhibitors (ACEi), Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs), β-blockers, and Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRAs) are examples of conventional pharmacotherapies that have significantly improved outcomes in HFrEF over the past three decades by addressing maladaptive neurohormonal activation [5]. In the PARADIGM-HF study, the use of Angiotensin Receptor- Neprilysin Inhibitors (ARNIs), such as sacubitril/valsartan, further decreased hospitalization and mortality as compared to ACEi [5]. Despite these developments, a number of restrictions still exist. In real-world populations, the one-year mortality rate following HF diagnosis surpasses 20%, many patients continue to have symptoms, and hospitalization rates are still high [18]. It is noteworthy that treatments that exhibit strong benefits in HFrEF have continuously failed to reduce mortality in populations with HFpEF [9]. According to Solomon et al. [19], even ARNI therapy in HFpEF, as demonstrated in PARAGON-HF, produced only slight improvements in secondary outcomes without reaching the primary endpoint. These drawbacks emphasize the necessity of treatment approaches that work via different pathways than neurohormonal blocking.

A therapeutic gap in the management of heart failure is demonstrated by the continued high rates of morbidity and mortality in spite of the best available medical treatment. This disparity is particularly significant in HFpEF, which currently makes up almost half of all HF cases globally and is expected to grow as the population ages and metabolic comorbidities including obesity, diabetes, and hypertension rise [20]. The unsatisfactory performance of conventional medicines in HFpEF indicates the need for targets other than neurohormonal pathways. The intricate interactions among myocardial energetics, systemic inflammation, renal failure, and vascular stiffness must be addressed by novel therapeutics. Because of their many benefits that go beyond lowering blood sugar, such as osmotic diuresis, natriuresis, metabolic modulation, anti-inflammatory qualities, and renal protection, sodium-glucose linked 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have become promising drugs in this regard [4]. They are a paradigm-shifting treatment that can close this long-standing therapeutic gap because of their consistent efficacy across the range of HF phenotypes [21] (Figure 2 & Table 1).

Figure 2:Main current gaps in heart failure pharmacological treatment. Source: Severino et al. [21].

Table 1:Classification and clinical characteristics of heart failure phenotypes.

Pharmacology of SGLT2 inhibitors

The innovative pharmacological family known as Sodium- Glucose Linked 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors was first created to Treat Type 2 Diabetic Mellitus (T2DM), but their applications in cardiovascular and renal medicine have quickly grown. By preventing glucose reabsorption in the proximal renal tubules, these medicationswhich include dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, canagliflozin, and ertugliflozin-cause glucosuria and mild drops in blood glucose levels [7]. Their therapeutic effects, however, go well beyond glycemic control, especially when it comes to the management of Heart Failure (HF), according to later seminal research [19]. A paradigm shifts in addressing the intricate pathophysiology of heart failure across its manifestations is provided by their pleiotropic effects, which include hemodynamic, metabolic, renal, and antiinflammatory actions [22].

Since 90% of filtered glucose is normally reabsorbed in the proximal convoluted tubule, this is where SGLT2 inhibitors mostly work. Independent of insulin secretion, these drugs reduce plasma glucose levels by increasing urine glucose excretion through selective inhibition of the SGLT2 protein [23]. In addition to enhancing glycemic control, this method lowers glucotoxicity and related oxidative stress, two major causes of vascular and cardiac damage in diabetic and heart failure patients. Crucially, patients with severe β-cell dysfunction and chronic diabetes can still benefit from SGLT2 inhibitors due to their insulin-independent activity [24].

The benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors for the heart and kidneys seem to be mostly unaffected by blood sugar levels, even though their ability to reduce blood sugar is well known. According to clinical research, these substances lower body weight, blood pressure, and intravascular volume without triggering the sympathetic nervous system [6]. According to Heerspink et al. [22], they also improve natriuresis and osmotic diuresis, which lower preload and afterload, two processes that are essential for managing heart failure. By lowering intraglomerular pressure, delaying the fall of eGFR, and reducing the likelihood of progression to endstage kidney disease, SGLT2 inhibitors improve renal outcomes in addition to their hemodynamic effects [25]. These benefits to the kidneys are especially important because of the reciprocal relationship between CKD and heart failure, sometimes known as the cardiorenal syndrome.

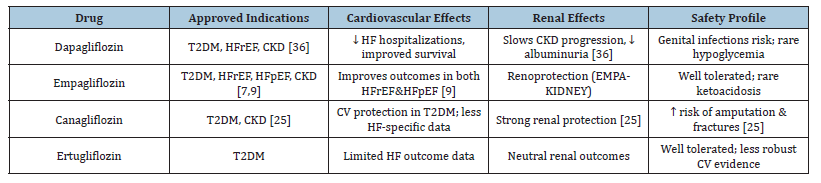

Numerous SGLT2 inhibitors have been assessed in extensive randomized controlled trials, and each one has shown notable improvements in renal and cardiovascular outcomes. Regardless of diabetes status, patients with HFrEF who took dapagliflozin in the DAPA-HF study had a significantly lower risk of cardiovascular death or worsening HF [19]. Empagliflozin was initially shown to lower cardiovascular mortality in patients with existing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME study. It also demonstrated advantages in HF patients with both preserved and lowered ejection fraction [7,9]. Though initial use was moderated by concerns about amputation risk, canagliflozin, as studied in the CANVAS program, showed decreases in HF hospitalization and provided kidney protection [6]. Even though it has been examined less, ertugliflozin has demonstrated similar effects on metabolism and the kidneys, and research into its potential involvement in heart failure is still ongoing [26]. When combined, these drugs have completely changed the way that diabetes and heart failure are treated.

Although there are some concerns to be aware of, the safety profile of SGLT2 inhibitors is generally good. Genitourinary infections, which are caused by glucosuria and are usually minor and treatable with current therapy, are among the most frequent adverse events [7]. Particularly in elderly persons or those using concurrent diuretics, volume depletion might result from osmotic diuresis, requiring close monitoring of blood pressure and renal function [25]. Euglycemic Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA), particularly in patients with insulin-treated diabetes or during acute illness, is an uncommon but dangerous complication [8]. Although watchfulness is still necessary, later research has not reliably confirmed early worries of an elevated incidence of lower limb amputation with canagliflozin [6]. Given their substantial protective effects on the heart and kidneys, the overall benefit to risk ratio clearly favors their use (Table 2).

Table 2:Pharmacological profile of SGLT2 inhibitors.

Clinical evidence supporting SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure

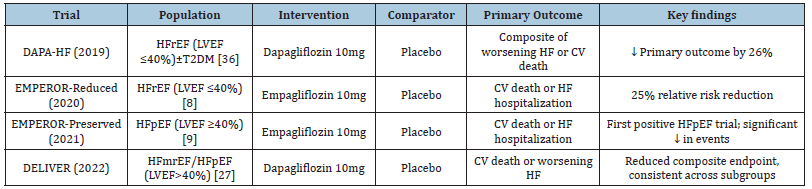

A strong collection of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses that consistently show cardiovascular and renal benefits throughout the spectrum of ejection fraction have fueled the clinical adoption of SGLT2 inhibitors in the management of Heart Failure (HF). These medications were first created as antidiabetic medicines, but regardless of glycemic status, they have demonstrated significant decreases in heart failure hospitalization, cardiovascular mortality, and enhancements in quality of life [7,19]. This section summarizes the key findings from seminal studies in Heart Failure with Maintained Ejection Fraction (HFpEF), Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF), and pooled analyses that support their widespread safety and effectiveness in clinical settings.

Landmark trials in HFrEF (DAPA-HF, EMPEROR-Reduced, CANVAS sub-analyses)

The first HF study specifically designed to assess an SGLT2 inhibitor in patients with HFrEF, irrespective of diabetes status, was the DAPA-HF trial. When compared to a placebo, dapagliflozin significantly decreased the composite endpoint of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death by 26%, with benefits being consistent across subgroups [19]. These results were supported by the EMPEROR-Reduced study, which used empagliflozin to halt the decline in renal function and reduce the primary endpoint by 25% [8]. Crucially, even in individuals without diabetes, these advantages were noticeable, proving that SGLT2 inhibition has cardioprotective benefits separate from glycemic management. A class effect across SGLT2 inhibitors may be implied by previous results from the CANVAS study with canagliflozin, which also showed decreases in HF hospitalization [6]. Collectively, these studies made SGLT2 inhibitors a new cornerstone of HFrEF treatment based on guidelines.

Trials in HFpEF (EMPEROR-Preserved, DELIVER)

Historically, treatments for Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) have not proven successful. SGLT2 inhibitors, however, have shown the first reliable improvements in this difficult trait. Empagliflozin decreased the risk of cardiovascular death or HF hospitalization by 21% in individuals with LVEF>40%, according to the EMPEROR-Preserved study [9]. This experiment represented a paradigm shift in treatment as it was the first to show a significant benefit in HFpEF. In a similar vein, dapagliflozin decreased the same composite endpoint by 18% across a broad range of ejection fractions, including patients with slightly reduced EF (HFmrEF), according to the DELIVER study [27]. The effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitors as treatments for all HF phenotypes, including those where traditional neurohormonal therapy had previously failed, was solidly proven by these trials.

Meta-analyses and pooled outcomes

Numerous meta-analyses have synthesized data from extensive RCTs, demonstrating the SGLT2 inhibitors’ steady benefits in HF. Combining data from the EMPEROR and DAPA-HF/DELIVER studies, Vaduganathan M et al. [28] showed that both reduced and preserved EF populations experienced improved renal outcomes, a significant decrease in HF hospitalization, and a decrease in cardiovascular death. In a similar vein, Zelniker TA et al. [29] found that, independent of preexisting diabetes, SGLT2 inhibitor trials resulted in a 23% decrease in HF hospitalization. These results demonstrate the consistency and strength of SGLT2 inhibitors’ cardioprotective benefits, hence bolstering their incorporation into modern HF treatment plans.

Effects on hospitalization, mortality and quality of life

SGLT2 inhibitors enhance patient-centered outcomes in addition to conventional endpoints. According to the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), both DAPA-HF and EMPEROR-Reduced showed notable reductions in symptoms and health-related quality of life [30]. Particularly noteworthy were decreases in recurring heart failure hospitalizations, which lessened the medical strain brought on by repeated admissions. Despite being less significant than hospitalization reductions, mortality benefits are nevertheless clinically significant, particularly when combined with other guideline-directed therapy and the synergistic effects of SGLT2 inhibitors [8]. When taken as a whole, these results highlight the wide-ranging effects of SGLT2 inhibitors, both in terms of prolonging life and enhancing the quality of life for HF patients (Table 3).

Table 3:Landmark clinical trials of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure.

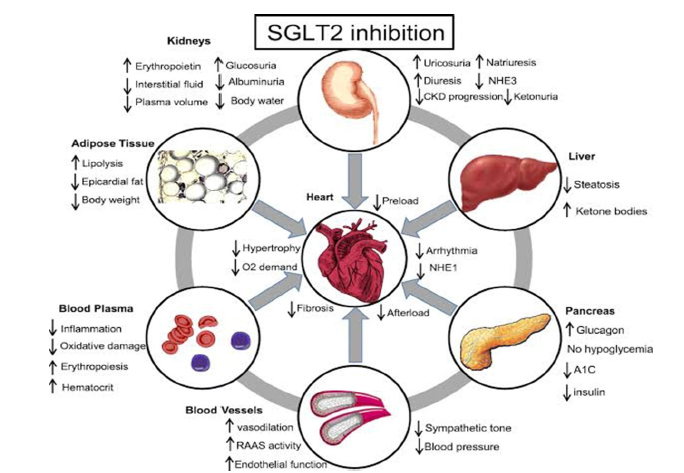

Mechanistic insights: Why SGLT2 inhibitors work in HF

Important issues concerning the underlying mechanisms of action of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have been highlighted by their consistent advantages across a variety of heart failure (HF) patients. In contrast to traditional treatments that mostly focus on neurohormonal activation, SGLT2 inhibitors work via a variety of mechanisms that include metabolic, hemodynamic, renal, and anti-inflammatory activities. Both diabetic and nondiabetic individuals with HF benefit from these processes, which are mainly independent of glycemic management [4,8]. Comprehending these pleiotropic effects offers vital information about how SGLT2 inhibitors close long-standing therapeutic gaps and support a paradigm change in the treatment of heart failure.

Hemodynamic effects: Natriuresis, osmotic diuresis, and preload/afterload reduction

The effect of SGLT2 inhibitors on hemodynamics was one of the first mechanisms of HF to be identified. These medications cause osmotic diuresis and natriuresis by inhibiting the proximal tubules’ ability to reabsorb glucose and salt, which lowers plasma volume and causes interstitial congestion [21]. This lowers preload, which relieves systemic and pulmonary congestion, and reduces afterload by reducing blood pressure slightly without triggering reflex sympathetic activation [31]. By preferentially mobilizing interstitial fluid rather than intravascular fluid, SGLT2 inhibitors produce a more balanced volume reduction than loop diuretics, which primarily reduce intravascular volume and may stimulate neurohormonal systems [4]. This special characteristic assists HF patients with their dyspnea and exercise intolerance symptoms while reducing neurohormonal activation.

Metabolic effects: Shift to ketone utilization and improved myocardial energetics

SGLT2 inhibitors improve myocardial energetics by having positive metabolic effects in addition to hemodynamics. These substances cause a mild fasting-like metabolic state that is marked by elevated ketogenesis and lipolysis [24]. Compared to free fatty acids or glucose, ketones provide a higher ATP yield per oxygen molecule, making them more energy-efficient substrates for the failing heart [32]. Myocardial efficiency is increased and energy mismatch, a defining feature of HF, is decreased by this metabolic change. Furthermore, improvements in insulin sensitivity and decreases in epicardial adipose tissue may lessen cardiac stress and systemic metabolic dysfunction. Together, these metabolic effects which are not dependent on reducing blood sugar-help to restore heart function and alleviate symptoms.

Renal protection and modulation of the cardiorenal axis

The course of heart failure is largely dependent on the cardiorenal axis because kidney dysfunction makes inflammation, fluid overload, and neurohormonal activation worse. SGLT2 inhibitors offer strong renal protection via different mechanisms than conventional treatments. Afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction and drops in intraglomerular pressure result from their restoration of tubuloglomerular feedback by decreasing salt reabsorption [25]. According to Heerspink HJL et al. [22], this results in decreased albuminuria, a slower drop in estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR), and a lower chance of developing end-stage renal disease. Crucially, as better kidney function lessens congestion, decreases maladaptive neurohormonal activation, and improves overall heart failure outcomes, renal benefits seem to work in concert with cardiovascular protection [8].

Anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic effects

New research shows that SGLT2 inhibitors have antiinflammatory and antifibrotic properties, which help to explain why they are good for the heart. According to Paulus et al. [14], myocardial fibrosis and chronic low-grade inflammation are the main causes of unfavorable remodeling in HF, especially in HFpEF. SGLT2 inhibitors attenuate oxidative stress and decrease circulating indicators of inflammation, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α). According to preclinical research, these medications reduce heart fibrosis and enhance diastolic function by blocking the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Reductions in inflammation of the epicardial fat may also improve coronary microvascular function and reduce local cytokine release. All of these actions work together to reduce the progression of HF, reverse maladaptive remodeling, and enhance long-term results [33] (Figure 3).

Figure 3:Mechanisms of action of SGLT2 inhibitors in HF. Source: Wojcik & Warden [33].

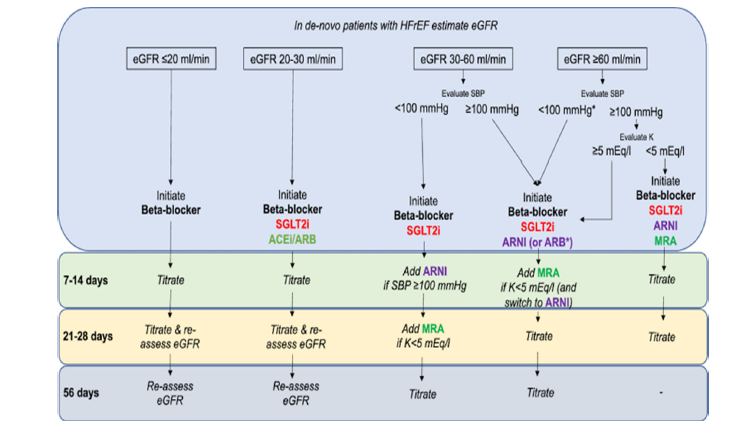

Integration into heart failure guidelines and clinical practice

The swift development of high-quality evidence supporting Sodium-Glucose Linked Transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors in Heart Failure (HF) led to their almost instantaneous inclusion in global clinical guidelines. SGLT2 inhibitors’ compatibility with current disease-modifying medications, their application in patients with comorbid conditions like diabetes or Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), and the reliability of randomized controlled trials across HF phenotypes are all reflected in this integration. We provide a summary of the following: dosing/initiation techniques, phenotypeand comorbidity-specific guidelines, placement with other HF treatments, and practical considerations for practical application.

The main HF treatment now recommended by major guideline bodies is SGLT2 inhibitors. When clinically appropriate, early introduction of dapagliflozin and empagliflozin is advised by the 2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Heart Failure Guideline (with a targeted update that followed) [34] as foundational medicines for HFrEF [12]. Additionally, SGLT2 inhibitors were promoted to a Class I recommendation for HFrEF (with level of evidence A) in the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline. Based on DELIVER and EMPEROR-Preserved evidence, Class IIa recommendations were made for HF with modestly reduced EF (HFmrEF) and HFpEF [35]. There has been a paradigm shift with these unified updates: ARNI/ACEi, β-blockers, and MRAs are now the recommended disease-modifying treatments for heart failure, coupled with SGLT2 inhibitors [8,12].

HF pharmacotherapy is increasingly being presented by guidelines and expert consensus as a multi-pillar strategy, where SGLT2 inhibitors are included in the core regimen rather than as an optional add-on [12]. According to the current method, four drug classes should be started right away for HFrEF: ARNI (or ACEi/ ARB), β-blocker, MRA, and SGLT2 inhibitor. Target doses should then be titrated as tolerated [35]. This paradigm acknowledges that SGLT2 inhibitors do not require up-titration (fixed daily dose), which makes implementation easier, and places more emphasis on early combination therapy to achieve quick risk reduction than rigorous sequential sequencing.

The fact that SGLT2 benefits are unaffected by diabetes status is a significant practical advancement; DAPA-HF and EMPERORReduced have both shown effectiveness in patients without diabetes, and EMPEROR-Preserved/DELIVER has extended benefits to HFpEF/HFmrEF [8,9,27,36]. SGLT2 inhibitors are therefore advised for qualified patients in all EF groups. Importantly, HF analyses and trials (DAPA-CKD, CREDENCE) demonstrated renal protection and acceptable safety for patients with CKD, a common comorbidity. In mild-to-moderate CKD, guidelines recommend that SGLT2 inhibitors be started down to eGFR thresholds (typically ~20-30mL/min/1.73m², depending on the agent) and continued with monitoring rather than being stopped [22,25,37]. However, clinicians should evaluate renal function after beginning and adhere to local product labeling.

Concurrent therapies, blood pressure, eGFR, and volume status should all be taken into account when choosing a patient. Prior to starting, doctors usually check blood pressure and renal function, discuss the diuretic dosage (to lower the danger of volume depletion), and give patients genital hygiene advice to lower the risk of mycotic infections. In patients at increased risk, routine monitoring involves evaluating renal function and electrolytes within 1-2 weeks of beginning; nevertheless, the initial mild drop in eGFR is hemodynamic and stabilizes in the majority of patients [22]. Because SGLT2 inhibitors have few pharmacologic interactions with ARNI, β-blockers, or MRAs, they can be used in combination. However, doctors should be cautious when treating patients who are hypotensive or have low volume and modify diuretics accordingly.

Uptake is still subpar despite the endorsement of guidelines because of physician familiarity, prescribing inertia, and expense. In many areas, cost and payer coverage are common barriers that could prevent early implementation (ACC tools; clinical practice surveys). Effective tactics to promote appropriate use include multidisciplinary HF clinics, hospital-based initiation approaches, and educational initiatives. To guide best practices, registries and implementation studies monitor uptake and results [38] (Figure 4).

Figure 4:SGLT2 inhibitors guidelines. Source: Cavallari et al. [38].

Challenges and considerations

Despite the fact that SGLT2 inhibitors are usually well tolerated, some side effects need to be closely watched. The most prevalent are osmotic diuresis-related events that cause volume depletion and vaginal mycotic infections, which are more common in women [7,36]. In rare cases, euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis can happen, particularly in individuals receiving insulin or after extended fasting [8]. Therefore, prevention counseling and awareness are crucial.

Widespread adoption is nevertheless hampered by cost, especially in low- and middle-income nations where healthcare systems face challenges with drug affordability [39]. Inequities in access continue to be a major global concern, even though costeffectiveness studies in high-income environments show the longterm utility of SGLT2 inhibitors due to decreased hospitalizations and increased survival.

SGLT2 inhibitors are not as widely used in HF as recommended by guidelines, despite compelling trial data. According to registry data, underprescription is prevalent, especially among women, those without diabetes, and older patients [40]. Obstacles include patient adherence issues, physician unfamiliarity, and treatment inertia. These gaps might be filled with the aid of interdisciplinary HF programs and better education.

The long-term safety of SGLT2 inhibitors in advanced heart failure, their use in patients with severe chronic kidney disease or dialysis, and their impact on underrepresented groups like the elderly or people with numerous comorbidities are among the unresolved issues [4]. It is anticipated that ongoing trials will shed light on these ambiguities and broaden the scope of treatment.

Future directions

To better understand the function of SGLT2 inhibitors in Heart Failure (HF), numerous extensive clinical trials are now in progress. For example, empagliflozin’s potential to reduce heart failure or cardiovascular death after an acute myocardial infarction is being assessed by the EMPACT-MI study [30]. Post-MI applications are also being investigated by registries like DAPA-MI. The best time and patient groups to start therapy will be determined in part by these investigations. SGLT2 inhibitors will probably be used in combination with other innovative medication classes in future strategies. According to preclinical and early clinical research, ARNI+SGLT2i or SGLT2i+GLP-1RA may have synergistic effects by addressing complementary pathways such inflammation, neurohormonal activation, and metabolic dysfunction. In HF patients, these combinations may further lower residual risk.

According to new research, SGLT2 inhibitors may be useful for both acute decompensated heart failure and chronic heart failure [41,42]. According to the EMPULSE experiment, short-term results were enhanced when empagliflozin was started in the hospital. In order to move treatment toward prevention, trials are also looking into the possible use of SGLT2 inhibitors in stage B HF, which is pre- HF with structural heart disease but no symptoms. Future practice may shift toward precision prescription as our knowledge grows, identifying individuals who are most likely to benefit from SGLT2 inhibitors based on genetic profiles, biomarkers, or phenotyping [4]. This customized strategy may maximize results while reducing unfavorable incidents and expenses [43] (Table 4).

Table 4:Summary of key findings on SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure.

Conclusion

The development of SGLT2 inhibitors has changed the therapeutic environment for the treatment of heart failure. SGLT2 inhibitors provide advantages across the range of HF symptoms by acting through complementary mechanisms involving hemodynamic, metabolic, renal, and anti-inflammatory effects, in contrast to standard treatments that predominantly target neurohormonal pathways. Their position as a cornerstone therapy has been reinforced by strong data from seminal randomized controlled trials that routinely show improvements in quality of life, cardiovascular mortality, and HF hospitalizations. The paradigm shift in HF management is highlighted by updated worldwide guidelines that now place SGLT2 inhibitors alongside well-known medications like ARNIs, β-blockers, and MRAs. Cost, long-term safety data, and the underrepresentation of specific patient categories are still issues, though. All things considered, including SGLT2 inhibitors into standard treatment is an important step toward more thorough, patient-centered HF management and emphasizes the necessity of ongoing research to maximize their application in a variety of therapeutic contexts.

References

- Chen QF, Chen L, Katsouras CS, Liu C, Shi J, et al. (2025) Global burden of heart failure and its underlying causes in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2021. European heart journal-Quality of Care and Clinical Outcomes 11(4): 493-509.

- Sussman JB, Wilson LM, Burke JF, Ziaeian B, Anderson TS (2024) Clinical characteristics and current management of U.S. adults at elevated risk for heart failure using the PREVENT equations: A cross-sectional analysis. Ann Intern Med 178(1): 144-147.

- Lindberg F, Benson L, Dahlström U, Lund LH, Savarese G (2025) Trends in heart failure mortality in Sweden between 1997 and 2022. European Journal of Heart Failure 27(2): 366-376.

- Butler J, Zannad F, Filippatos G, Anker SD, Packer M (2020) Totality of evidence in trials of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors in the patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Implications for clinical practice. European Heart Journal 41(36): 3398-3401.

- McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, et al. (2014) Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. The New England Journal of Medicine 371(11): 993-1004.

- Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, De Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, et al. (2017) Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine 377(7): 644-657.

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, Bluhmki E, et al. (2015) Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine 373(22): 2117-2128.

- Packer M, Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Pocock SJ, et al. (2020) Cardiovascular and renal outcomes with empagliflozin in heart failure. The New England Journal of Medicine 383(15): 1413-1424.

- Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G, Ferreira JP, Bocchi E, et al. (2021) Empagliflozin in heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction. The New England Journal of Medicine 385(16): 1451-1461.

- Lam CS, Solomon SD (2014) The middle child in heart failure: Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (40-50%). European Journal of Heart Failure 16(10): 1049-1055.

- Rabizadeh S, Nakhjavani M, Esteghamati A (2019) Cardiovascular and renal benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors: A narrative review. International Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism 17(2): e84353.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, et al. (2023) 2023 Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. European Heart Journal 44(37): 3627-3639.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, et al. (2021) ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Developed by the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European Journal of Heart Failure 42(36): 3599-3726.

- Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C (2013) A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 62(4): 263-271.

- Lam CSP, Voors AA, de Boer RA, Solomon SD, van Veldhuisen DJ (2018) Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: From mechanisms to therapies. European Heart Journal 39(30): 2780-2792.

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, et al. (2016) 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. European Heart Journal 37(27): 2129-2200.

- Ranek J, Berthiaume JM, Kirk JA, Lyon RC, Sheikh F, et al. (2022) Pathophysiology of heart failure and an overview of therapies. Cardiovascular Pathology, (5th edn), Academic Press, USA, pp. 149-221.

- Savarese G, Vasko P, Jonsson Å, Edner M, Dahlström U, et al. (2019) The swedish heart failure registry: A living, ongoing quality assurance and research in heart failure. Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences 124(1): 65-69.

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, Ge J, Lam CSP, et al. (2019) Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The New England Journal of Medicine 381(17): 1609-1620.

- Borlaug BA (2020) Evaluation and management of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature Review Cardiology 17(9): 559-573.

- Severino P, D’Amato A, Prosperi S, Myftari V, Canuti ES, et al. (2023) Heart failure pharmacological management: Gaps and current perspectives. Journal of Clinical Medicine (JCM) 12(3):1020.

- Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, et al. (2020) Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. The New England Journal of Medicine 383(15): 1436-1446.

- Vallon V, Thomson SC (2017) Targeting renal glucose reabsorption to treat hyperglycaemia: The pleiotropic effects of SGLT2 inhibition. Diabetologia 60(2): 215-225.

- Ferrannini E, Muscelli E, Frascerra S, Baldi S, Mari A, et al. (2014) Metabolic response to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition in type 2 diabetic patients. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 124(2): 499-508.

- Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, et al. (2019) Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. The New England Journal of Medicine 380(24): 2295-2306.

- Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo-Jack S, Mancuso J, Huyck S, et al. (2020) Cardiovascular outcomes with ertugliflozin in type 2 diabetes. The New England Journal of Medicine 383(15): 1425-1435.

- Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Claggett B, de Boer RA, DeMets D, et al. (2022) Dapagliflozin in heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. The New England Journal of Medicine 387(12): 1089-1098.

- Vaduganathan M, Docherty KF, Claggett BL, Jhund PS, de Boer RA, et al. (2022) SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure: A comprehensive meta-analysis of five randomised controlled trials. Lancet 400(10354): 757-767.

- Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, Im K, Goodrich EL, et al. (2019) SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet 393(10166): 31-39.

- Kosiborod MN, Jhund PS, Docherty KF, Diez M, Petrie MC, et al. (2020) Effects of dapagliflozin on symptoms, function and quality of life in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: Results from the DAPA-HF trial. Circulation 141(2): 90-99.

- Verma S, McMurray JJV (2018) SGLT2 inhibitors and mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit: A state-of-the-art review. Diabetologia 61(10): 2108-2117.

- Bedi KC, Snyder NW, Brandimarto J, Aziz M, Mesaros C, et al. (2016) Evidence for intramyocardial disruption of lipid metabolism and increased myocardial ketone utilization in advanced human heart failure. Circulation 133(8): 706-716.

- Wojcik C, Warden BA (2019) Mechanisms and evidence for heart failure benefits from SGLT2 inhibitors. Curr Cardiol Rep 21(10): 130.

- European Society of Cardiology (2023) 2023 Focused update of the 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 44(37): 3627-3639.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, et al. (2022) 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 145(18): e895-e1032.

- McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, Køber L, Kosiborod MN, et al. (2019) Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. The New England Journal of Medicine 381(21): 1995-2008.

- Armillotta M, Angeli F, Paolisso P, Belmonte M, Raschi E, et al. (2025) Cardiovascular therapeutic targets of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors beyond heart failure. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 270: 108861.

- Cavallari I, Crispino SP, Segreti A, Ussia GP, Grigioni F (2023) Practical guidance for the use of SGLT2 inhibitors in heart failure. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 23(6): 609-621.

- Li X, Hoogenveen R, El Alili M, Knies S, Wang J, et al. (2023) Cost-effectiveness of SGLT2 inhibitors in a real-world population: A MICADO model-based analysis using routine data from a GP registry. Pharmacoeconomics 41(10): 1249-1262.

- Greene SJ, Butler J, Albert NM, DeVore AD, Sharma PP, et al. (2018) Medical therapy for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The CHAMP-HF registry. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 72(4): 351-366.

- Talha KM, Anker SD, Butler J (2023) SGLT-2 Inhibitors in heart failure: A review of current evidence. Int J Heart Fail 5(2): 82-90.

- Greene Stephen J, Butler J, Kosiborod MN (2024) Chapter 3: Clinical trials of sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors for treatment of heart failure. The American Journal of Medicine 137(2): S25-S34.

- Zhou H, Wang S, Zhu P, Hu S, Chen Y, et al. (2018) Empagliflozin rescues diabetic myocardial microvascular injury via AMPK-mediated inhibition of mitochondrial fission. Redox biology 15: 335-346.

© 2025 Moses Adondua Abah. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)