- Submissions

Full Text

Open Access Research in Anatomy

From 2D Imaging to Precision Surgery: Individualized 3D Reconstruction of Hepatic Structures

Sergio EF¹*, Manuel NS1 and Enrique C³

1Department of Surgery, University Hospital of Vigo Álvaro Cunqueiro, Spain

2Department of Electronics and Computation, University of Santiago de Compostela, Spain

*Corresponding author: Sergio Estévez-Fernández, Surgery Department, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo Álvaro Cunqueiro. Galician Sur Health Research Institute, University of Santiago de Compostela, Avda, Clara Campoamor S/N, Vigo, Pontevedra. Spain

Submission: December 12, 2025;Published: December 19, 2025

ISSN: 2577-1922

Volume3 Issue 2

Abstract

Modern hepatobiliary surgery relies on an increasingly precise understanding of hepatic anatomy. Three- Dimensional (3D) anatomical reconstruction from medical imaging has enabled the transition from static, 2D anatomy to dynamic computational anatomy. This article reviews how advanced processing of CT and MRI images, enhanced by Deep Learning, is improving morphological studies, making them more individualized. It analyzes how 3D hepatic image reconstruction can reveal vascular and biliary variants, as well as complex venous drainage maps that are difficult to assess in 2D images. The results of recent studies addressing anatomical variants, the classification of portal branching, venous congestion in oncological resections, the accuracy of liver volume calculation, and improved surgical outcomes are discussed. “Virtual 3D anatomy” should currently be the standard for obtaining the most precise hepatic anatomy in the living patient.

Keywords:3D reconstruction; Computational anatomy; Anatomical variants; Hepatic segmentation; Volumetry; Venous maps; CT

Keywords: 3D/2D: Three-Dimensional/Two-Dimensional; CT: Computed Tomography (Spanish: TC); RLV: Remnant Liver Volume (Spanish: VHR); CNN: Convolutional Neural Networks; LDLT: Living Donor Liver Transplantation; HCC: Hepatocellular Carcinoma; AR: Augmented Reality (Spanish: RA)

Introduction

Historically, knowledge of hepatic anatomy was based on cadaveric dissections and classical anatomical classifications such as the one proposed by Couinaud. Currently, morphological characterization is based on imaging tests, primarily Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). These techniques, utilizing multiphasic acquisition protocols (arterial, portal, and venous) and sub-millimeter slices, offer hundreds of detailed images to visualize the complex biliary and vascular network within the hepatic parenchyma. However, the interpretation of 2D images often fails when attempting to convert oblique or tortuous structures into 3D, leading to errors in identifying vascular variants, positioning space-occupying lesions within the liver, and calculating the volumes of different hepatic segments. 3D reconstruction from 2D radiological images is not merely a visual tool; it aims to be a method of research and non-invasive anatomical simulation that allows for “virtual dissections” of the various vascular, biliary, and parenchymal structures of the liver. This technology has enabled the identification of vascular and bilio-portal anatomical variants [1], improving the understanding of hepatic structures beyond 2D images and the static images found in classical texts.

Discussion

Contemporary liver surgery has evolved thanks, in part, to an increasingly precise knowledge of hepatic anatomy. This is fundamentally due to image processing, moving from static 2D radiological interpretation toward dynamic computational anatomy. This paradigm shift begins with segmentation methodology; while historically dependent on laborious manual tracing, the recent integration of Artificial Intelligence algorithms and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) has allowed for the automation of structure detection with unprecedented precision. Authors such as Li [2] & Zheng [3] have demonstrated that these deep learning models not only streamline workflow but also achieve the definition of third- and fourth-order vascular pedicles with similarity coefficients exceeding 95%, revealing a micro-anatomy that remained hidden in the grayscale of the twodimensional image. This ability to build a “virtual hepatic twin” has improved liver volumetry calculation, providing a highly precise functional liver prediction tool. In the context of major resections, the literature validates that 3D volumetry offers an almost exact correlation with the actual volume of the treated liver, overcoming the limitations of traditional volumetric calculation formulas [4].

Wang [5] highlight the value of this preoperative assessment for surgical planning, a fact corroborated by Fang [6], who showed in patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) that the use of 3D reconstruction significantly reduces operative time and blood loss by facilitating the anticipation of potential problems regarding vascular dissection during liver resection. Studies, such as the one conducted by Oshita [7], have evidenced that classical classifications of portal vein anatomy are insufficient to address individual variability (Figure 1). Through 3D simulation, it is possible to identify and classify complex variants-such as trident branching or independent access to posterior segmentsthat are frequently undetectable in 2D axial slices. Thanks to 3D reconstruction, resect ability criteria for liver lesions are better evaluated through the incorporation of “venous drainage maps.” As established by Mise [8], parenchyma preservation depends not only on arterial and portal venous inflow but also on venous drainage. Their findings demonstrate that ignoring areas of venous congestion following the transaction of major hepatic veins leads to an overestimation of the remnant liver’s functional capacity, which can lead to serious complications for the patient. This philosophy of anatomical precision in liver evaluation extends to Living Donor Liver Transplantation (LDLT), where Yoshioka [9] confirmed that virtual planning is the standard for defining transection lines that ensure biliary and vascular integrity for both the donor and the recipient. Finally, this digital data can be made haptic through 3D printing of the liver, aiding in planning, training, teaching, and surgical rehearsal [10]. However, the final challenge for intraoperative navigation using Augmented Reality (AR) remains soft tissue deformation, requiring elastic registration algorithms to maintain model fidelity during surgical manipulation [11].

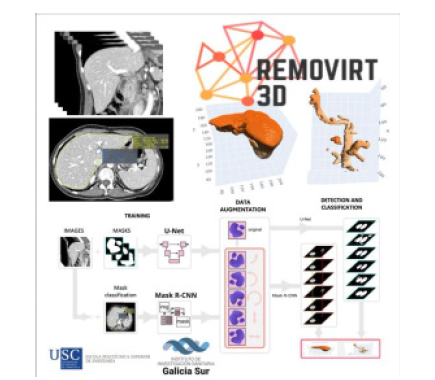

The future of this technology lies in total automation, clinical interoperability, and the evolution toward dynamic “digital twins,” which will allow for the simulation of the liver’s physiological and hemodynamic response before surgery. An example is the growing emergence of research projects, such as REMOVIRT H3D (3D Hepatic Virtual Reconstruction and Modeling), which seek to reflect these advances in anatomical study into clinical practice. Furthermore, addressing soft-tissue deformation is clinically vital because the liver is a pliable organ that changes shape significantly during respiration and surgical manipulation. If these deformations are not corrected via elastic registration algorithms, the preoperative 3D model will fail to overlay accurately onto the real organ during surgery, potentially leading to navigation errors and compromising patient safety.

Figure 1:Workflow of REMOVIRT 3D: AI-based segmentation and classification of medical images for 3D reconstruction. The process integrates U-Net and Mask R-CNN architectures for mask generation and classification, followed by augmentation and detection steps to enable accurate visualization of anatomical structures.

Conclusion

Current scientific evidence positions 3D reconstruction as indispensable for advanced anatomical research of the liver. Studies confirm that three-dimensional analysis overcomes the spatial limitations of conventional 2D imaging, allowing for precise characterization of variability in Glissonian pedicles and venous drainage territories. This deep understanding of the vascular architecture and the complex relationships of intra-parenchymal hepatic structures creates the necessary anatomical basis to precisely predict functional volumes as well as vascular and biliary relationships, thereby improving clinical safety regarding potential diagnostic and therapeutic decisions concerning the liver.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no personal conflicts of interest. However, regarding institutional funding, the REMOVIRT H3D project is funded by the Spanish State Research Agency (PID2022-142709OAC22/ PID2022-142709OB-C21).

References

- Mori K, Deguchi S (2011) Computer-assisted planning of liver surgery: Principles and applications. HPB (Oxford) 13(6): 381-389.

- Gul S, Khan MS, Bibi A, Khandakar A, Ayari MA, et al. (2022) Deep learning techniques for liver and liver tumor segmentation: A review. Comput Biol Med 147: 105620.

- Zeng YZ, Liao SH, Tang P, Zhao YQ, Liao M, et al. (2018) Automatic liver vessel segmentation using 3D region growing and hybrid active contour model. Comput Biol Med 97: 63-73.

- Cremese R, Godard C, Be Nichou A, Blanc T, Quemada I, et al. (2025) Virtual reality-augmented differentiable simulations for digital twin applications in surgical planning. Sci Rep 15(1): 24377.

- Banchini F, Capelli P, Hasnaoui A, Palmieri G, Romboli A, et al. (2024) 3-D reconstruction in liver surgery: A systematic review. HPB (Oxford) 26(10): 1205-1215.

- Zeng X, Tao H, Dong Y, Zhang Y, Yang J, et al. (2024) Impact of three-dimensional reconstruction visualization technology on short-term and long-term outcomes after hepatectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A propensity-score-matched and inverse probability of treatment-weighted multicenter study. Int J Surg 110(3): 1663-1676.

- Senne M, Sgourakis G, Molmenti EP, Schroeder T, Beckebaum S, et al. (2022) Portal and hepatic venous territorial mapping in healthy human livers: Virtual three-dimensional computed tomography size-shape-topography study. Exp Clin Transplant 20(9): 826-834.

- Mise Y, Aloia TA, Brudvik KW, Schwarz L, Vauthey JN, et al. (2014) Parenchymal-sparing hepatectomy in colorectal liver metastasis: The importance of the venous drainage map. Annals of Surgery 260(5): 883-891.

- Kuroda S, Kihara T, Akita Y, Kobayashi T, Nikawa H, et al. (2020) Simulation and navigation of living donor hepatectomy using a unique three-dimensional printed liver model with soft and transparent parenchyma. Surg Today 50(3): 307-313.

- Witowski JS, Pędziwiatr M, Major P (2017) Cost-effective, personalized, 3D-printed liver model for preoperative planning before laparoscopic liver hemihepatectomy. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 12(12): 2047-2054.

- Gholizadeh M, Bakhshali MA, Mazlooman SR, Aliakbarian M, Gholizadeh F, et al. (2023) Minimally invasive and invasive liver surgery based on augmented reality training: A review of the literature. J Robot Surg 17(3): 753-763.

© 2025 Sergio EF. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)