- Submissions

Full Text

Open Access Biostatistics & Bioinformatics

Analysis and Control of a Cholera Disease Model

Lakshmi N Sridhar*

Chemical Engineering Department, University of Puerto Rico, USA

*Corresponding author: Lakshmi N Sridhar, Chemical Engineering Department, University of Puerto Rico, Mayaguez, PR 00681, Puerto Rico, USA

Submitted: November 03, 2025; Published: December 01, 2025

ISSN: 2578-0247 Volume4 Issue 2

Abstract

In this study, bifurcation analysis and multi-objective nonlinear model predictive control is performed on a cholera disease model. Bifurcation analysis is a powerful mathematical tool used to deal with the nonlinear dynamics of any process. Several factors must be considered, and multiple objectives must be met simultaneously. The MATLAB program MATCONT was used to perform the bifurcation analysis. The MNLMPC calculations were performed using the optimization language PYOMO in conjunction with the state-of-the-art global optimization solvers IPOPT and BARON. The bifurcation analysis revealed the existence of a limit point. The MNLMC converged to the utopia solution. The limit point (which causes multiple steady-state solutions from a singular point) is very beneficial because it enables the multiobjective nonlinear model predictive control calculations to converge to the Utopia point (the best possible solution) in the model.

Keywords:Bifurcation; Optimization; Control; Cholera

Background

Cholera is one of the oldest and most devastating infectious diseases in human history, caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. This acute diarrheal illness continues to afflict millions of people worldwide, particularly in regions with inadequate sanitation, unsafe drinking water, and poor hygiene infrastructure. The disease has shaped public health systems, driven advances in epidemiology, and remains a major global health challenge despite being preventable and treatable. Understanding cholera involves examining its microbiological origins, transmission dynamics, clinical presentation, and the social and environmental conditions that facilitate its persistence. Cholera is caused primarily by Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139, which produce a potent enterotoxin known as cholera toxin. This toxin is responsible for the profuse watery diarrhea characteristic of the disease. The bacterium is a curved, gram-negative rod with a single polar flagellum that enables motility, a feature that aids its colonization of the small intestine. Once ingested, typically through contaminated water or food, Vibrio cholerae passes through the stomach and reaches the small intestine, where it adheres to the epithelial cells of the intestinal mucosa. There it releases cholera toxin, which activates adenylate cyclase in host cells, leading to the accumulation of cyclic AMP and the secretion of massive amounts of water and electrolytes into the intestinal lumen. The result is the rapid onset of severe diarrhea that can lead to dehydration and death if not promptly treated. Clinically, cholera manifests after an incubation period of a few hours to five days. The disease ranges in severity from mild, self-limiting diarrhea to a life-threatening illness characterized by profuse, watery stools often described as “rice-water” because of their pale appearance and small flecks of mucus. Patients can lose up to a litter of fluid per hour, leading to rapid dehydration, sunken eyes, wrinkled skin, low blood pressure, and shock. Without treatment, death can occur within hours. However, with appropriate rehydration therapy, mortality can be kept below 1 percent. Most infected individuals remain asymptomatic or develop only mild symptoms, but they can still excrete the bacteria in their feces for several days, contributing to the spread of infection in their communities. The transmission of cholera is predominantly waterborne. Outbreaks often occur in settings where drinking water is contaminated with fecal matter, particularly in areas affected by poverty, conflict, or natural disasters. Contaminated food, especially raw or undercooked seafood from contaminated waters, can also serve as a source of infection. The bacterium thrives in aquatic environments, particularly in brackish water and estuaries, where it can associate with plankton and shellfish. Seasonal variations in temperature and rainfall can influence cholera transmission, with epidemics often coinciding with monsoon seasons or periods of flooding that disrupt sanitation systems.

Historically, cholera has caused seven major pandemics since the early nineteenth century, beginning with the first pandemic in 1817, which spread from the Ganges delta in India to much of Asia and the middle east. Subsequent pandemics reached Europe, Africa, and the Americas, facilitated by global trade and colonization. The disease profoundly influenced the development of modern public health measures. During the 1854 outbreak in London, British physician john snow famously traced the source of infection to a contaminated water pump on broad street, laying the foundation for the field of epidemiology and demonstrating the importance of clean water in preventing disease. Despite significant progress in water sanitation and hygiene in many parts of the world, cholera remains endemic in several regions, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and parts of Latin America. The persistence of cholera in the modern era underscores the link between disease and inequality. Populations living in slums, refugee camps, and areas affected by conflict are especially vulnerable because of inadequate access to clean water and healthcare. In many developing countries, outbreaks are also exacerbated by political instability and poor infrastructure. Natural disasters such as earthquakes and cyclones can destroy sanitation systems and contaminate water supplies, as was evident in the major cholera outbreak in Haiti following the 2010 earthquake.

Climate change further complicates the picture by influencing rainfall patterns, sea temperatures, and the ecology of Vibrio cholerae in coastal waters, potentially expanding the regions at risk for outbreaks. Treatment of cholera is straightforward but requires prompt action. The cornerstone of therapy is rehydration, either through Oral Rehydration Salts (ORS) for mild to moderate cases or intravenous fluids for severe dehydration. The goal is to replace the lost fluids and electrolytes and prevent shock. Antibiotics such as doxycycline or azithromycin can reduce the duration and severity of illness and lower bacterial shedding, though they are secondary to rehydration. Zinc supplementation is particularly beneficial in children, as it reduces the duration and volume of diarrhea. Prevention, however, is the most effective long-term strategy. Ensuring access to safe water, improving sanitation facilities, and promoting hygiene practices such as handwashing are essential public health measures. In recent years, Oral Cholera Vaccines (OCVs) have become a valuable tool in controlling outbreaks and preventing endemic transmission. The World Health Organization (WHO) has prequalified several OCVs, including Dukoral, Shanchol, and Euvichol, which provide protection for up to three years. Mass vaccination campaigns have proven effective in high-risk populations and emergency settings, such as refugee camps or areas recovering from natural disasters. However, vaccination alone cannot eliminate cholera without addressing the underlying determinants of the disease, such as poverty and inadequate infrastructure.

Global efforts to eradicate cholera have intensified in the past decade. The WHO launched the Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC), which set an ambitious target to reduce cholera deaths by 90 percent and eliminate transmission in twenty countries by 2030. Achieving this goal requires coordinated actions across sectors, including investments in water and sanitation infrastructure, strengthened disease surveillance, community engagement, and rapid response teams to contain outbreaks. Technological innovations, such as mobile health platforms for real-time reporting and predictive modeling of outbreaks, are helping authorities detect and respond to cholera more effectively. Despite these advances, challenges remain. Weak healthcare systems, limited laboratory capacity, and lack of political commitment in some regions hinder effective cholera control. Stigma and misinformation can also delay treatment-seeking behavior. Moreover, as urbanization continues at a rapid pace, the growth of informal settlements without adequate sanitation creates new breeding grounds for the disease. Addressing these structural issues requires sustained international collaboration, financial investment, and a commitment to social equity. Cholera is far more than a bacterial infection; It reflects the social, environmental, and economic vulnerabilities that persist across the world. The bacterium Vibrio cholerae may be the immediate cause, but the deeper roots lie in poverty, poor sanitation, and neglect of basic public health infrastructure. The fact that a disease known for centuries and easily prevented still causes outbreaks today highlights the global disparities in access to clean water and healthcare. While advances in treatment and vaccines have saved countless lives, the ultimate victory against cholera will depend on ensuring that every person, regardless of where they live, can drink clean water, practice good hygiene, and access prompt medical care. Cholera’s story is one of human resilience and scientific progress, but it is also a call to action to build a world where no one dies from a preventable disease..

Miller [1], modelled optimal intervention strategies for cholera,” Javidi [2] studied a fractional-order cholera model. Isere [3] developed an optimal control model for the outbreak of cholera in Nigeria. Edward and Nyerere [4] developed a mathematical model for the dynamics of cholera with control measures. Llanes et al. [5] demonstrated the low detection of vibrio cholerae carriage in healthcare workers returning to 12 Latin American countries from Haiti. Ochoche [6], developed a mathematical model on the control of cholera using hygiene consciousness as a strategy. Namawejje [7], modelled optimal control of cholera disease under the interventions of vaccination, treatment and education awareness. Idoga [8] analyzed the factors contributing to the spread of cholera in developing countries. Panja [9] performed an optimal control analysis of a cholera epidemic model. Ganesan [10] investigated the cholera surveillance and estimation of burden of cholera. Lemos-Paiao [11] used a case study of Yemen’s cholera outbreak to perform optimal control calculations of aquatic diseases. Abubakar [12] researched the optimal control analysis of treatment strategies of the dynamics of cholera. In this work, bifurcation analysis and multi-objective nonlinear model predictive control is performed on a cholera disease model described in Abubakar [12]. The paper is organized as follows. First, the model equations are presented, followed by a discussion of the numerical techniques involving bifurcation analysis and Multi-Objective Non-Linear Model Predictive Control (MNLMPC). The results and discussion are then presented, followed by the conclusions.

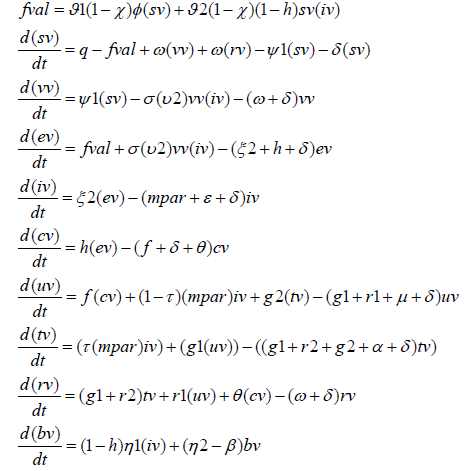

Model Equations (Abubakar [12])

In this model, sv, vv, ev, iv, cv, uv, tv, rv, bv, represent susceptible individuals, vaccinated individuals, exposed individuals, infected individuals, hygiene conscious individuals, untreated vibrio cholerae carries, infected individuals under treatment, recovered individuals, and concentration of Vibrio cholerae bacteria in food and water consumed by the human population.

The model Equations are

The parameters q;δ ;ϑ1;ϑ 2;θ ;h;η 2;η1;β ; f ;k; g1; g2;r1;r2;ε ;μ;α ;mpar;ψ1;ω;χ ;ξ 2;φ ;τ represent, human recruitment rate, non-cholera human death rate, rate of ingesting Vibrio cholerae bacteria from contaminated food and water consumed by the human population, rate of getting Vibrio cholerae bacteria through human-to-human interactions, rate of recovery of hygiene-conscious individuals, hygiene consciousness of individuals, rate of Vibrio cholerae decrease, rate at which infected individuals increase, Vibrio cholerae bacteria in the environment, rate of generating Vibrio cholerae bacteria in the environment, rate of freedom from Vibrio cholerae by the hygiene-conscious individuals, concentration of cholera pathogen that yields 50% chance of individual developing cholera disease, progression of recovery of treated individuals to untreated Vibrio cholerae carriers, rate of interruption of treatment, recovery rate of untreated Vibrio cholerae carriers, recovery of treated cholera patients, disease induced death rate for individuals in iv class, disease induced death rate for individuals in uv class, disease induced death rate for individuals in tv class, rate of movement of the infected class, rate of vaccine, rate of waning out of the vaccine induced immunity, rate at which the vaccine reduces infection, cholera awareness program, rate of exposure to infection, the fraction( bv/(k+bv)), fraction of early infected individuals.

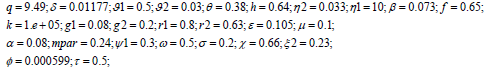

The base parameters are

Bifurcation Analysis

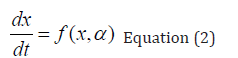

The MATLAB software MATCONT is used to perform the bifurcation calculations. Bifurcation analysis deals with multiple steady-states and limit cycles. Multiple steady states occur because of the existence of branch and limit points. Hopf bifurcation points cause limit cycles. A commonly used MATLAB program that locates limit points, branch points, and Hopf bifurcation points is MATCONT (Dhooge et al. [13]; Dhooge et al. [14]). This program detects Limit points (LP), Branch Points (BP), and Hopf bifurcation points(H) for an ODE system

Let the bifurcation parameter be. Since the gradient is orthogonal to the tangent vector,

The tangent plane at any point w=[w1,w2,w3,w4,......wn+1]must satisfy

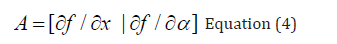

Aw = 0 Equation (3) Where A is

where is the Jacobian matrix. For both limit and branch points, the Jacobian matrix must be singular.

For a limit point, there is only one tangent at the point of

singularity. At this singular point, there is a single non-zero vector,

y, where Jy=0. This vector is of dimension n. Since there is only one

tangent the vector

must align with . Since

Jwˆ = Aw = 0 Equation (5)

the n+1th component of the tangent vector wn+1 at a Limit

Point (LP).

For a branch point, there must exist two tangents at the

singularity. Let the two tangents be z and w. This implies that

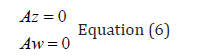

Equation (6)

Consider a vector v that is orthogonal to one of the tangents

(say w). v can be expressed as a linear combination of z and

w(v =α z +β w) . Since Az = Aw = 0 ; Av = 0 and since

w and v are orthogonal, wTv = 0 . Hence

Equation (6)

Consider a vector v that is orthogonal to one of the tangents

(say w). v can be expressed as a linear combination of z and

w(v =α z +β w) . Since Az = Aw = 0 ; Av = 0 and since

w and v are orthogonal, wTv = 0 . Hence  which implies that B is singular.

which implies that B is singular.

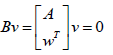

Hence, for a Branch Point (BP) the matrix  must be singular.

must be singular.

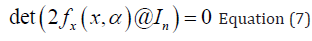

At a Hopf bifurcation point,

@ indicates the bialternate product while In is the n-square identity matrix. Hopf bifurcations cause limit cycles and should be eliminated because limit cycles make optimization and control tasks very difficult. More details can be found in Kuznetsov ([15,16]) and Govaerts [17].

Multi-Objective Non-Linear Model Predictive Control (MNLMPC)

The rigorous Multi-Objective Non-Linear Model Predictive Control (MNLMPC) method developed by Flores Tlacuahuaz [18] was used.

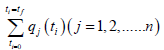

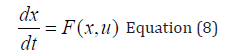

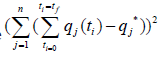

Consider a problem where the variables  must be optimized simultaneously for a dynamic problem

must be optimized simultaneously for a dynamic problem

tf being the final time value, and n the total number of

objective variables and u the control parameter. The single objective

optimal control problem is solved individually optimizing each of

the variables  The optimization of

The optimization of

will lead to

the values q*j. Then, the Multi-Objective Optimal Control (MOOC)

problem that will be solved is

will lead to

the values q*j. Then, the Multi-Objective Optimal Control (MOOC)

problem that will be solved is

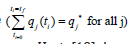

This will provide the values of u at various times. The first

obtained control value of u is implemented and the rest are

discarded. This procedure is repeated until the implemented and

the first obtained control values are the same or if the Utopia point

where  is obtained.

is obtained.

Pyomo, Hart [19] is used for these calculations. Here, the differential equations are converted to a Nonlinear Program (NLP) using the orthogonal collocation method The NLP is solved using IPOPT [20] and confirmed as a global solution with BARON [21].

The steps of the algorithm are as follows

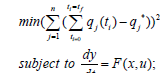

1. Optimize  and obtain q*j.

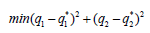

2. Minimize

and obtain q*j.

2. Minimize and get the control values

at various times.

3. Implement the first obtained control values

4. Repeat steps 1 to 3 until there is an insignificant

difference between the implemented and the first obtained value of

the control variables or if the Utopia point is achieved. The Utopia

point is when

and get the control values

at various times.

3. Implement the first obtained control values

4. Repeat steps 1 to 3 until there is an insignificant

difference between the implemented and the first obtained value of

the control variables or if the Utopia point is achieved. The Utopia

point is when  . Sridhar LN [22] demonstrated

that when the bifurcation analysis revealed the presence of limit

and branch points the MNLMPC calculations to converge to the

utopia solution. For this, the singularity condition, caused by the

presence of the limit or branch points was imposed on the costate

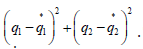

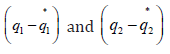

equation [23]. If the minimization of q1 lead to the value

q*1 and the minimization of q2 lead to the value q*2. The MNLPMC

calculations will minimize the function

. Sridhar LN [22] demonstrated

that when the bifurcation analysis revealed the presence of limit

and branch points the MNLMPC calculations to converge to the

utopia solution. For this, the singularity condition, caused by the

presence of the limit or branch points was imposed on the costate

equation [23]. If the minimization of q1 lead to the value

q*1 and the minimization of q2 lead to the value q*2. The MNLPMC

calculations will minimize the function  . The

multi-objective optimal control problem is

. The

multi-objective optimal control problem is  subject

to

subject

to  Equation (10)

Equation (10)

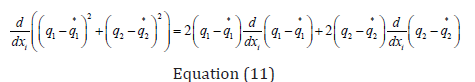

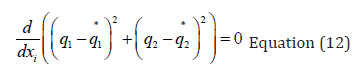

Differentiating the objective function results in

The utopia point requires that both  are

zero. Hence

are

zero. Hence

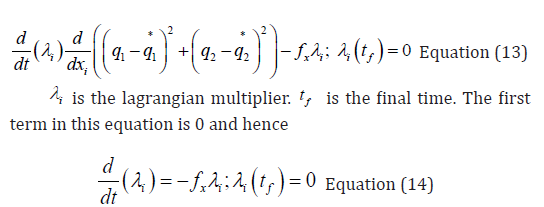

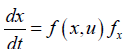

The optimal control co-state equation (Upreti; 2013) is

At a limit or a branch point, for the set of ODE  is singular. Hence there are two different vectors-values for [λi]

where

is singular. Hence there are two different vectors-values for [λi]

where  . In between there is a vector

[λi]

where

. In between there is a vector

[λi]

where  . This coupled with the boundary condition

λi (tf ) = 0 will lead to [λi]=0

= This makes the problem an unconstrained optimization problem, and the optimal solution is

the Utopia solution.

. This coupled with the boundary condition

λi (tf ) = 0 will lead to [λi]=0

= This makes the problem an unconstrained optimization problem, and the optimal solution is

the Utopia solution.

Result and Discussion

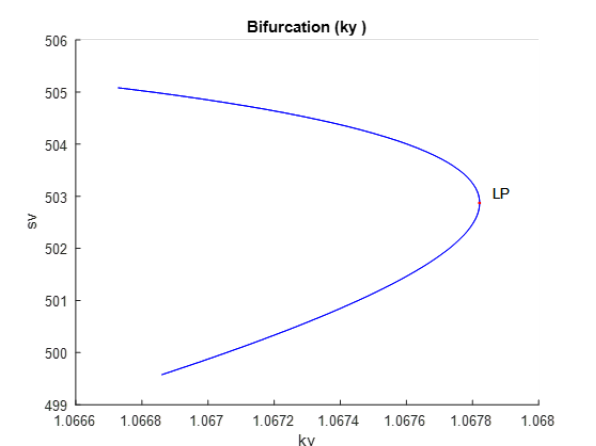

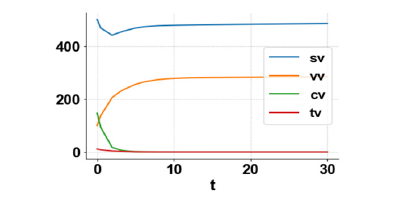

With χ as the bifurcation parameter, a limit point was found at, (sv, vv, ev, iv, cv, uv, tv, rv, bv, χ ) values of (502.871851, 293.301333, 0.668780, 0.431145, 0.410858, 0.337287, 0.078581, 0.941338, 38.803019, 1.067821) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:χ is bifurcation parameter.

For the MNLMPC χ is the control parameter, and

were minimized individually, and led to values

of 0 and 0. The overall optimal control problem will involve the

minimization of

were minimized individually, and led to values

of 0 and 0. The overall optimal control problem will involve the

minimization of  was minimized

subject to the equations governing the model. This led to a value of

zero (the Utopia point). The MNLMPC value of the control variable

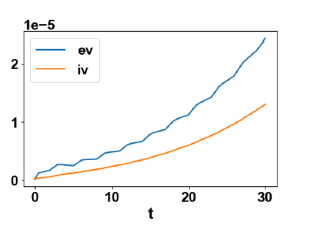

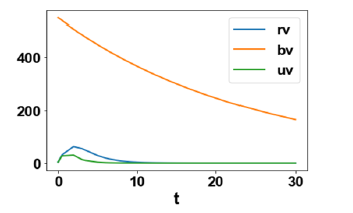

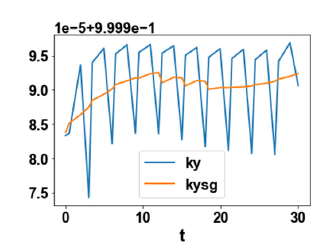

χ is 0.999983. The MNLMPC profiles are shown in (Figure 2). The

control profiles of χ exhibited noise and this was remedied using

the savitzky-golay filter to produce the smooth profiles χ sg . The

presence of the limit point and is beneficial because it allows the

MNLMPC calculations to attain the Utopia solution, validating the

analysis of Sridhar [22].

was minimized

subject to the equations governing the model. This led to a value of

zero (the Utopia point). The MNLMPC value of the control variable

χ is 0.999983. The MNLMPC profiles are shown in (Figure 2). The

control profiles of χ exhibited noise and this was remedied using

the savitzky-golay filter to produce the smooth profiles χ sg . The

presence of the limit point and is beneficial because it allows the

MNLMPC calculations to attain the Utopia solution, validating the

analysis of Sridhar [22].

Figure 2a:MNLMPC sv, vv, cv, tv profiles.

Figure 2b:MNLMPC ev, iv profiles.

Figure 2c:MNLMPC rv, bv, uv profiles.

Figure 2d:MNLMPC χ χ sg profiles.

Conclusion

Bifurcation analysis and Multi-Objective Non-Linear Model Predictive Control (MNLMPC) studies on a cholera disease model. The bifurcation analysis revealed the existence of a limit point. The limit point (which cause multiple steady-state solutions from a singular point) are very beneficial because they enable the multi-objective nonlinear model predictive control calculations to converge to the Utopia point (the best possible solution) in the models. A combination of bifurcation analysis and Multi-objective Non-Linear Model Predictive Control (MNLMPC) for a cholera disease model is the main contribution of this paper.

Data Availability Statement

All data used is presented in the paper

Conflict of Interest

The author, Dr. Lakshmi N Sridhar has no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Sridhar thanks Dr. Carlos Ramirez and Dr. Suleiman for encouraging him to write single-author papers.

References

- Neilan RLM, Elsa S, Gaff H, Fister KR, Lenhart S (2010) Modeling optimal intervention strategies for cholera. Bull Math Biol 72(8): 2004-2018.

- Javidi M, Ahmad B (2014) A study of a fractional-order cholera model. Applied Mathematics & Information Sciences 8(5): 2195-2206.

- Isere AO, Joseph EO, Daniel O (2014) Optimal control model for the outbreak of cholera in Nigeria. African Journal of Mathematics and Computer Science Research 7(2): 24-30.

- Edward S, Nyerere N (2015) A mathematical model for the dynamics of cholera with control measures. Applied and Computational Mathematics 4(2): 53-63.

- Llanes R, Somarriba L, Hernández G, Bardaji Y, Aguila A, et, al. (2015) Low detection of vibrio cholerae carriage in healthcare workers returning to 12 Latin American countries from Haiti. Epidemiol Infect 143(5): 1016-1019.

- Jeffrey OM, Chinwendu ME, Benjamin AT (2015) A mathematical model on the control of cholera: Hygiene consciousness as a strategy. Journal of Mathematics and Computer Science 5(2): 172-187.

- Namawejje H, Obuya E, Luboobi LS (2018) Modeling optimal control of cholera disease under the interventions of vaccination, treatment and education awareness. Journal of Mathematics Research 10(5): 137-152.

- Idoga PE, Toycan M, Zayyad MA (2019) Analysis of factors contributing to the spread of cholera in developing countries. Eurasian J Med 51(2): 121-127.

- Prabir P (2019) Optimal control analysis of a cholera epidemic model. Biophysical Reviews and Letters 14(1): 27-48.

- Ganesan D, Gupta SS, Legros D (2020) Cholera surveillance and estimation of burden of cholera. Vaccine 38(1): A13-A17.

- Paião APL, Silva CJ, Torres DFM, Ezio V (2020) Optimal control of aquatic diseases: A case study of Yemen’s cholera outbreak. Journal of Optimization Theory and Applications 185(3): 1008-1030.

- Fakai AS, Ibrahim MO (2022) Optimal control analysis of treatment strategies of the dynamics of cholera. Journal of Optimization 2022(1): 1-26.

- Dhooge A, Govaerts W, Kuznetsov AY (2003) MATCONT: A matlab package for numerical bifurcation analysis of ODEs. ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software 29(2): 141-164.

- Dhooge A, Govaerts W, Kuznetsov YA, Mestrom W, Riet AM (2003) CL_MATCONT: A continuation toolbox in Matlab. SAC ’03 pp.161-166.

- Kuznetsov YA (1998) Elements of applied bifurcation theory. Springer Nature Link.

- Kuznetsov YA (2009) Five lectures on numerical bifurcation analysis. Utrecht University, Netherlands.

- Govaerts WJF (2000) Numerical methods for bifurcations of dynamical equilibria. SIAM.

- Flores TA, Pilar M, Martin RT (2012) Multi-objective nonlinear model predictive control of a class of chemical reactors. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 51(17): 5891-5899.

- William EH, Jean PW, David LW, Gabriel AH, John DS, et al. (2017) Pyomo-optimization modeling in python. Springer Optimization and Its Applications.

- Wächter A, Biegler LT (2005) On the implementation of an interior-point filter line-search algorithm for large-scale nonlinear programming. Mathematical Programming 106: 25-57.

- Mohit T, Sahinidis NV (2005) A polyhedral branch-and-cut approach to global optimization. Mathematical Programming 103(2): 225-249.

- Sridhar LN (2024) Coupling bifurcation analysis and mulsti-objective nonlinear model predictive control. Austin Chem Eng 11(1): 01-07.

- Ranjan US (2013) Optimal control for chemical engineers. Taylor and Francis Group, pp. 1-309.

© 2025 Lakshmi N Sridhar. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)