- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Techniques in Nutrition and Food Science

Dietary Intake Assessment of Sugar in Several Pack Sizes of Carbonated Soft Drinks in Nigeria

Fregene Christopher*, Mahmood Sugra T, Ojji Dike and Adegboye Abimbola

Department of Medical Biochemistry and National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control, University of Abuja, Nigeria

*Corresponding author:Fregene Christopher, Department of Medical Biochemistry and National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control, University of Abuja, Nigeria

Submission: July 15, 2025;Published: August 19, 2025

ISSN:2640-9208Volume8 Issue 4

Abstract

Introduction: Obesity is estimated to affect over 22% of the adult population in Nigeria, which is ‘off

course’ to preventing this number from increasing. There is increasing concern that intake of added

sugars-particularly in the form of sugar-sweetened beverages-increases overall energy intake, leading to

an unhealthy weight gain (obesity) and increased risk of NCDs. The National Policy on Food Safety and

Quality and its Implementation Plan 2023 seeks to address this concern through its key activity to develop

and implement a national strategic plan/guideline for the reduction/reformulation of sugar in packaged

and processed foods as well as spices [1]. Pack sizes of sugar-sweetened beverages, particularly carbonated

soft drinks have increased substantially over the years with the current trend of 600ml bottles being

popularized in the Nigeria market. This “supersizing” phenomenon might be an important contributor

to the rise in obesity rates in Nigeria. Although there is national nutrition policy to reduce sugar intake

and content of packaged and processed foods, there is gap in implementation due to lack of policies that

regulate pack sizes of sugar-sweetened beverages. The World Health Organization recommends reducing

the intake of added sugars to less than 10% of total energy intake. Controlling pack sizes of carbonated

soft drinks may be a highly effective public health regulatory measure that could contribute to placing

Nigeria ‘on course’ towards achieving global target of reducing obesity. This study estimates the risk of

excessive sugar intake from several pack sizes of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria.

Methodology: The level of sugar in carbonated soft drinks was estimated by this study from on-pack

nutrition labels of brands most commonly available in the open markets and supermarkets in Nigeria

and daily soft drink consumption data from research studies. The assessment was done to evaluate

dietary sugar intake and calculate its associated risk to health from soft drink consumption using the

recommended methods in the Codex Food Safety Risk Analysis Manual and FAO Dietary Risk-Pesticide

Registration Toolkit. Comparison of the estimated dietary intake was made with the recommended

maximum level of sugar intake from the WHO Population Nutrient Intake Goals and the WHO Sugar

Guidelines.

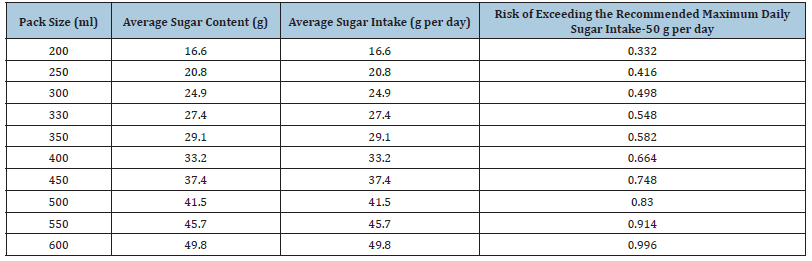

Result: The result shows that the average sugar content of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria is 8.3 g

per 100ml. It also shows that the estimated intake of sugar increases with pack size, from 16.6g per day

(200ml pack) to 49.8g per day (600ml pack). It is estimated that the risk of excessive sugar intake from

200ml to 250ml pack is low, from 300ml to 330ml pack is medium and from 35ml to 600ml pack is high.

A high-risk score warns of the possibility to exceed the WHO recommended maximum daily sugar intake

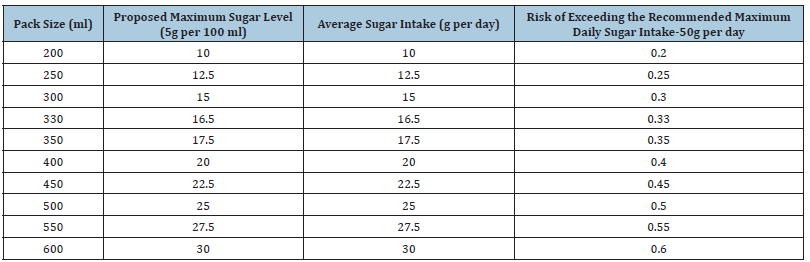

and indicates the need for risk management strategies. If the proposed maximum sugar level of 5g per

100ml of carbonated soft drinks is implemented, it is estimated that the risk of excessive sugar intake

from 200ml to 450ml pack is low, from 500ml to 550ml pack is medium and from 600ml pack is high.

The relative risk reduction is estimated to be 40%. This suggests that the likelihood of exceeding the

WHO recommended maximum daily sugar intake is 40% less if maximum sugar level for carbonated soft

drinks is set at 5g per 100ml. The implementation of the proposed maximum sugar level and pack size

cap is estimated to reduce significantly the intake of sugar from carbonated soft drinks and subsequently,

the risk of obesity associated with excessive intake of sugar. Finally, the result shows that carbonated soft

drinks are classified as excessive in free sugars. This further supports the suggestion that the consumption

of the drinks makes it more likely for the diet to exceed the WHO recommended sugar goal.

Conclusion and recommendation: This study concludes that consumption of carbonated soft drinks increases the risk of excessive sugar intake and unhealthy weight gain and is likely to be a major reason behind obesity rise in Nigeria. It recommends the establishment of pack size cap of 500ml with maximum sugar level of 5g per 100ml of the product.

Keywords:Dietary intake assessment; Added sugars; Soft drinks; WHO sugar guidelines; WHO African region nutrient profile model; National policy on food safety and quality

Introduction

Obesity is estimated to affect over 22% of the adult population in Nigeria, which is ‘off course’ to preventing this number from increasing and has showed limited progress towards achieving the target of reducing obesity among this population group. It is estimated that if the current trend continues, almost half of the Nigeria’s adult population could be obese by 2030. Worldwide, statistics are similar. This issue causes not only a burden on individuals, their health and families, but also affect society and the economy as a whole. Overcoming Obesity: An Initial Economic Assessment-a comprehensive review published by the McKinsey Global Institute-reports that the global economic impact from obesity is roughly US $2.0 trillion a year [2]. There is increasing concern that intake of added sugars- particularly in the form of sugar-sweetened beverages-increases overall energy intake and may reduce the intake of foods containing more nutritionally adequate calories, leading to an unhealthy diet, weight gain (obesity) and increased risk of NCDs (Figure 1). The National Policy on Food Safety and Quality and its Implementation Plan 2023 seeks to address this concern through its key activity to develop and implement a national strategic plan/guideline for the reduction/ reformulation of sugar in packaged and processed foods as well as spices [1]. Pack sizes (describe the portions in single packs offered/ sold to consumers) of sugar-sweetened beverages, particularly carbonated soft drinks have increased substantially over the years with the current trend of 600ml bottles being popularized in the Nigeria market. This “supersizing” phenomenon, now widespread, might be an important contributor to the rise in obesity rates in Nigeria. The reason why is that when presented with larger pack sizes, people tend to consume more. This is, among others, caused by “unit bias”, meaning that the pack size or quantity provided is automatically perceived to be the appropriate amount to consume [3]. It could also be that these larger pack sizes are associated with a corresponding increase in average sugar intake. Although there is national nutrition policy to reduce sugar intake and content of packaged and processed foods, there is gap in implementation due to lack of policies that regulate pack sizes of sugar-sweetened beverages [2]. The World Health Organization recommends reducing the intake of added sugars to less than 10% of total energy intake, which translates to less than 50g added sugar on a 2,000kcal diet per day [4]. Studies have shown that pack size control has impact to reduce obesity and promote behavior change [2]. A comprehensive analysis by the OECD confirmed this and favored smaller portion (pack) sizes as a public health tool to reduce consumption of energy-dense foods [3]. The German government already adopted this strategy in its approach to tackle diabetes and obesity among children and adolescents [5]. Controlling pack sizes of carbonated soft drinks, which are high in added sugars, may be a highly effective public health regulatory measure that could contribute to placing Nigeria ‘on course’ towards achieving global target of reducing obesity. This study estimates the risk of excessive sugar intake from several pack sizes of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria.

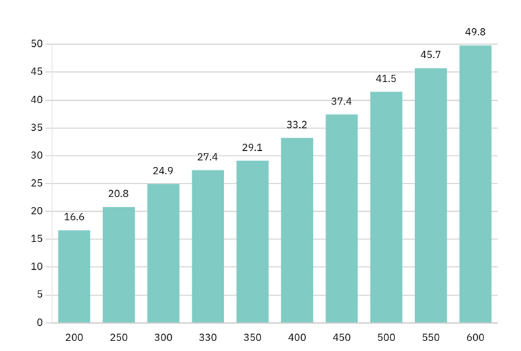

Figure 1:Average sugar intake from various pack sizes of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria. This chart shows that the average sugar intake from 600ml bottle is almost the same value as the WHO recommended maximum daily sugar intake of 50g per day on a 2000kcal diet. It suggests benchmarking pack size at 330ml to avoid the risk of excessive sugar intake from carbonated soft drinks.

Methodology

Sugar content of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria

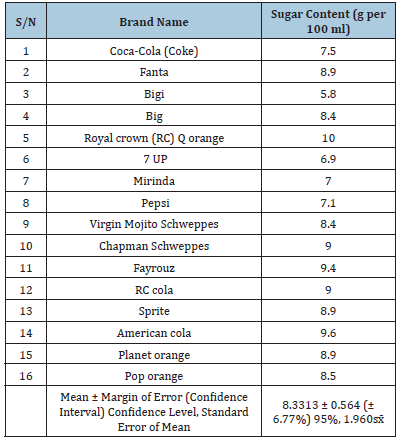

Data on sugar content was estimated from on-pack nutrition labels of several brands of soft drinks most commonly available in open markets and supermarkets in Nigeria (Table 1).

Table 1:Sugar content of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria.

Consumption of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria

Data on consumption was estimated to be 350ml from the study of VO Ansa.

Estimation of mean dietary sugar intake for the general population

Using the information on sugar content and consumption level, dietary sugar intake from soft drinks was estimated according to a methodology developed by Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) as stated below.

Calculation:

(Mean sugar content in g per 100ml of the soft drinks x consumption of the soft drinks in ml per day)/100).

Conversion factor

1 kcal=4.18 kj

Risk characterization

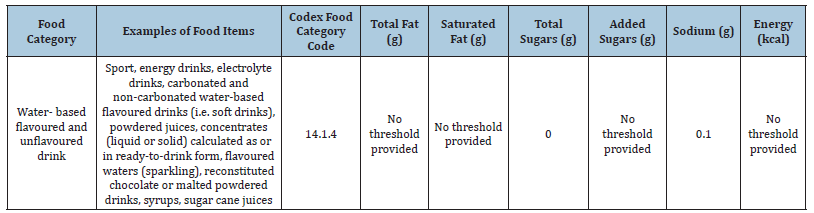

The risk was characterized by comparing the estimated dietary sugar intake with and expressed as a percentage of, the WHO Population Sugar Intake Goal (Table 2).

Table 2:The Nutrient Profile Model for the WHO African Region [10].

NB: Marketing is prohibited if thresholds exceed values per 100ml.

Relative intake (risk)

Dietary intake (risk) when soft drinks without proposed benchmark is consumed/Dietary intake (risk) when the soft drinks with proposed benchmark is consumed.

Relative intake (risk) reduction

(Dietary intake [risk] when soft drinks without proposed benchmark is consumed-Dietary intake [risk] when the soft drinks with proposed benchmark is consumed/Dietary intake [risk] when the soft drinks without proposed benchmark is consumed) x 100.

Dietary risk

Dietary risk is the estimated dietary intake expressed as a percentage of the WHO Population Sugar Intake Goal.

Result and Interpretation

The result shows that the average sugar content of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria is 8.3 g per 100 ml. This is not significantly difference from the value estimated in the study by Fregene Christopher et al., 2025. However, it is significantly higher than the value estimated in the study by [6]. This suggests a significant increase in sugar content over the years. The rise in sugar content is predicted to continue if regulatory actions are not taken and the sugar limit range of 7g/10ml -14g/100 ml for soft drinks recommended by the Standard Organization of Nigeria, as cited by the report of Abass Ohilebo, is not revised [6]. A study by [7] supports this predicted trend. The carbonated soft drink is considered to be excessive in added sugars according to the principles and rationale of Nutrient Profile Model for the WHO African Region.

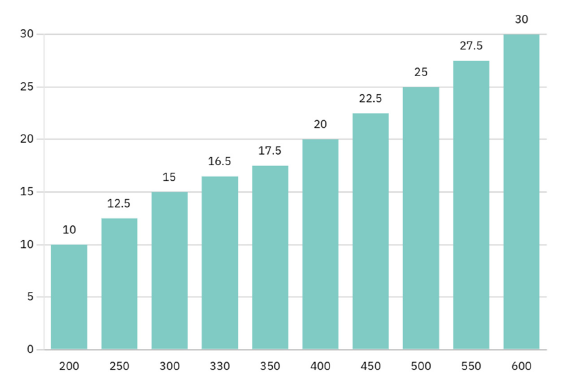

The contribution of added sugars to the product’s total energy is higher than 5%. The amount of energy (kcal) from added sugars in 100ml of the carbonated soft drink is estimated by this study to be 33.2 kcal, which is higher than 5% of total energy. If the proposed maximum sugar level is implemented, the amount of energy (kcal) from added sugars in 100ml of the product is estimated to be 20kcal, which appears to be lower than 5% of total energy. This means that the proposed measure could lead to significant reduction in sugar content. The results of this study further show that the estimated intake of sugar increases with pack size, from 16.6g per day (200ml pack) to 49.8g per day (600ml pack) (Figure 2). This suggests that the consumption of 600ml pack makes it most likely for the diet to be excessive not only in added sugars but also in energy (Calories). The amount of energy (kcal) from added sugars in 600ml pack is estimated by this study to be approximately 200kcal, which is equal to 10% of the average total daily energy intake. Hence, the need to set maximum sugar level in accordance with the principles of the Preamble of the General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Foods and Feed (GSCTFF), as the product contributes significantly to total dietary intake of sugar. This study estimated that the risk of excessive sugar intake from 200ml to 250ml pack is low, from 300ml to 330ml pack is medium and from 350ml to 600ml pack is high. A high-risk score warns of the possibility to exceed the WHO recommended maximum daily sugar intake and indicates the need for risk management strategies. If the proposed maximum sugar level of 5g per 100ml of carbonated soft drinks is implemented, it is estimated that the risk of excessive sugar intake from 200ml to 450ml pack is low, from 500ml to 550ml pack is medium and from 600ml pack is high. This suggests that the present trend of 600ml pack in the market poses serious risk to health, thus its elimination of 600ml pack from the market could possibility have a significant, positive health impact on the population. The relative risk reduction is estimated to be 40%. This suggests that the likelihood of exceeding the WHO recommended maximum daily sugar intake is 40% less if maximum sugar level for carbonated soft drinks is set at 5g per 100ml. The implementation of the proposed maximum sugar level and pack size cap is estimated to reduce significantly the intake of sugar from carbonated soft drinks and subsequently, the risk of obesity associated with excessive intake of sugar. A recently published modelling study measured the impact of reducing the serving size of all single serve Sugar Sweetened Beverages (SSB) to a maximum size of 250ml. It was shown that such a 250ml cap on single serve SSB could be an effective contribution to obesity prevention [8] (Table 3 & 4).

Figure 2:Maximum sugar intake from various pack sizes of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria when the recommended maximum sugar level is implemented. This chart shows that there is a significant reduction in sugar intake when a maximum sugar level of 5g per 100ml is implemented as a strategy for managing the risk of excess sugar intake from carbonated soft drinks. It shows that the maximum sugar intake from a 600ml bottle falls below the WHO recommended maximum daily sugar intake on a 2000kcal diet. It suggests benchmarking at 550ml with maximum sugar content of 5g per 100ml mitigates the risk of excessive sugar intake.

Table 3:Average sugar content from various pack sizes of carbonated soft drinks in Nigeria.

NB for risk category (proposed based on the probability line concept):

0=No risk

≤0.45=Low risk

>0.45-≤ 0.55=medium risk

> 0.55=high risk

≥1=certain

(200ml to 250ml pack daily consumption falls under low risk, 300ml to 330ml falls under medium risk. However, 350ml

to 600ml pack daily consumption falls under high risk, which warns of the possibility of exceeding the recommended

maximum and calls for risk management strategies. The risk of excessive sugar intake (hence, the risk of obesity) is

(maybe) increased with 600ml pack consumption).

Table 4:Maximum sugar content from various pack sizes of energy drinks in Nigeria NB for risk category (proposed based on the probability line concept):

0=No risk

≤0.45=Low risk

>0.45-≤ 0.55=medium risk

>0.55=high risk

≥1=certain

(350ml to 450ml pack daily consumption falls under low risk, which indicates “unlikely” to exceed the recommended

maximum. 500ml to 550ml pack daily consumption falls under medium risk, whereas 600 ml pack daily consumption

falls under high risk. This indicates predicted reduction in risk through proposed sugar content regulation).

Conclusion and Recommendation

This study concludes that consumption of carbonated soft drinks increases the risk of excessive sugar intake and obesity and is likely to be one of the major factors contributing to the obesity rise in Nigeria. The government and beverage industry play important roles in improving the nutrition and health of the population. The government needs to act by introducing the 500ml with 5g sugar per 100ml caps. The beverage industry needs to act by complying with these policies of government. This will contribute significantly to national efforts in reducing population burden of obesity and related non-communicable diseases such as Type 2 diabetes, achieving WHO global diet-related non-communicable disease targets and Nigeria’s vision of developing healthy, educated and productive Nigerians for a globally competitive Nation by 2030 [9- 19].

Assumption

A. The on-pack sugar content data reflect correct analytical

data.

B. Estimation of added sugars is based on the amount of

total sugars (carbohydrate) declared on product packaging.

The product is a food with no or a minimal amount of naturally

occurring sugars.

Acknowledgement

Prof. Dan Ramdath for paper review.

References

- Federal Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (2023) National policy on food safety and quality and its implementation plan. Abuja: Federal ministry of health and social welfare.

- Dobbs R, Sawers C, Thompson F (2014) Overcoming obesity: An initial economic analysis. McKinsey Global Institute, USA.

- OECD (2019) The heavy burden of obesity: The economics of prevention, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, France.

- FAO and WHO (2015) General Standard for Contaminants and Toxins in Foods and Feed (GSCTFF). Codex Alimentarius Commission, Rome.

- Deutscher Bundestag (2020) Launch of a national diabetes strategy: Targeted development of health promotion and prevention in Germany and care of diabetes mellitus.

- Ohilebo Abass (2024) Evaluation of sugar content of some soft drinks in Nigeria. Clin Med Bio Chem 10: 222.

- Sodamade A (2012) Assessment of sugar levels in different soft drinks: A measure to check national food security. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) 3(12): 567-569.

- Raghoebar S, Haynes A, Robinson E, Kleef EV, Vet E, (2019) Served portion sizes affect later food intake through social consumption norms. Nutrients 11(12): 2845.

- FAO and WHO (2006) Codex alimentarius commission-food safety risk analysis manual: Dietary risks: Pesticide registration toolkit. Rome.

- FAO and WHO (2019) Codex alimentarius commission-procedural manual twenty-seventh edition. Rome.

- Fregene Christopher, Mahmood Sugra T, Ojji Dike, Adegboye Abimbola (2025) Dietary intake assessment of sugar in carbonated soft drinks in Lagos, Nigeria. Nov Tech Nutri Food Sci 8(3): 853-858.

- Global Health Risks (2009) Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization, Switzerland.

- Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases (2014) Geneva: World Health Organization, Switzerland.

- Hauner H, Bechthold A, Boeing H, Bronstrup A, Buyken A, et al. (2015) Evidence-based guideline of the German Nutrition Society: Carbohydrate intake and prevention of nutrition-related diseases. Ann Nutr Metab 60(Suppl 1): 1-58.

- Malik VS, Pan A, Willett WC, Hu FB (2013) Sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain in children and adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 98(4): 1084–1102.

- Victor O Ansa, Maxwell U Anah, Wilfred O Ndifor (2008) Soft drink consumption and overweight/obesity among Nigerian adolescents. Elsevier 3(4): 191-196.

- World Health Organization (2018) Nutrient profile model for the WHO African Region: A tool for implementing WHO recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children. Brazzaville: WHO Regional Office for Africa.

- World Health Organization (2022) Global Nutrition Report. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- World Health Organization (2015) Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

© 2025 Fregene Christopher. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)