- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Approaches in Cancer Study

Integrating Mental Health Screening During Infusion Visits in a Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Clinic: Partnering with Nursing to Improve Access

Kelsey Largen1* and Katerina Levy2

1Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, NYU Langone Health, USA

22Department of Clinical Psychology, Long Island University CW Post, USA

*Corresponding author:Kelsey Largen, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, 2200 North Druid Hills Rd NE, Atlanta, GA, 30329, USA

Submission: November 07, 2025;Published: December 01, 2025

ISSN:2637-773XVolume8 Issue 4

Abstract

Background: Evidence-based screening helps to identify psychosocial factors important to treatment and facilitates referrals to psychosocial services. Screening is effective in a pediatric oncology setting, however, there are several barriers to implementation, including lack of time and resources.

Methods: Nurses administered mental health screenings to hematology/oncology patients ages 11-25 during routine infusion visits every three months. Data was collected from patients and nurses in addition to screening results.

Results: Out of 480 screenings conducted, 68 were positive on the PHQ-4, identifying 37 unique patients. These 37 patients then completed follow-up measures, yielding 18 patients with elevated scores on either the PHQ-9 (n= 12) or the GAD-7 (n=14); 8 patients had elevated scores on both measures. Results indicated that both patients and nurses felt that asking about mental health during medical visits was important, but nurses wanted more education on administering these measures.

Discussion: Partnering with nurses to administer mental health screenings can help to overcome barriers to implementation and identify children and adolescents at risk for anxiety and depression in a pediatric hematology/oncology clinic.

Keywords:Adolescents; Anxiety; Depression; Oncology; Hematology

Statement Summary

This quality improvement initiative found that partnering with nurses to administer mental health questionnaires helps to overcome barriers to implementation and identifies hematology/oncology patients that are exhibiting symptoms of anxiety and depression. This partnership allows for mental health screening to be conducted with a trusted healthcare professional that can seamlessly integrate the screening into their routine care.

Standards of care in pediatric hematology/oncology recommend regular screening of psychosocial risk in patients due to the adverse psychological effects that childhood cancer has on patients and families [1]. Evidence-based psychosocial screening helps to identify psychosocial factors important to treatment and facilitates referrals to psychosocial services [2-4] to prevent treatment gaps for patients [5]. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of screening in a pediatric oncology setting [6-8]. Research has contributed to the development of fifteen standards of psychosocial care for children diagnosed with cancer and their families such as receiving early, routine, and systematic assessment of psychosocial healthcare needs, creating access for patients to reach psychosocial providers (i.e., psychology and psychiatry) and providing developmentally appropriate information to patients prior to invasive medical procedures or treatment [1].

Progress on implementation of these psychosocial care standards in oncology clinics has been slow despite the wellestablished need for psychosocial care in this clinical setting, as a survey in 2016 indicated that only 25% of pediatric oncology programs in the United States utilize ongoing psychosocial assessment of youth with cancer [9]. A previous survey conducted in 2012 revealed less than 10% of oncology clinics were utilizing evidence-based mental health screenings with youth in their clinics [10]. Documented barriers to screening implementation include lack of time and resources [6,11], determining appropriate times to screen, and providing training in psychosocial risk [12].

In order to address these barriers, psychosocial screening programs should consider methods of seamlessly incorporating screening into a medical visit. Targeting patients at infusion visits allows for more time to complete the screening, as patients are often in clinic for several hours. Infusion nurses are uniquely qualified to administer screening measures, based on the relationship that they develop with patients and families. Due to the nature of their work, oncology nurses often are attuned to patients’ emotions and develop ways to determine whether their patient is distressed, such as looking for verbal or behavioral cues [13]. Using interdisciplinary models of care in which an overlap between skills exists between nurses and psychosocial providers enhances patient care and improves health-related quality of life [14].

In the current project, we aimed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of screening during infusion visits as part of patients’ routine care. We used an interdisciplinary model of care to guide our intervention which delineates the discipline-specific competencies and scopes of practice while highlighting comprehensive patientcentered interdisciplinary team activities [14] and has been shown to increase resource identification for adolescent and young adult oncology patients [15]. Patients attending infusion visits with a diagnosis of cancer or a blood disorder were screened every three months by their infusion nurse to assess their mental health. We aimed to identify patients with mental health concerns not currently in therapy who might benefit from referral to the psychology service.

Materials and Methods

Screening was conducted as part of standard clinical care. The screening process was reviewed via a program development/quality improvement framework and thus did not require IRB review or oversight. Quality improvement procedures were evaluated using an ethical framework and were deemed to be suitable. The Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQuIRE) guidelines were followed in reporting the results of this paper.

Design and sample

The project was conducted at a pediatric hematology/oncology clinic within a large children’s hospital in an urban location in the northeastern part of the country. Nursing staff administered the Patient Health Questionnaire- 4 (PHQ-4) during routine infusion visits for children with cancer and blood disorders ages 11 and up every three months. The PHQ-4 is a four-item questionnaire composed of the first two questions of the Patient Health Questionairre-9 (PHQ-9), assessing symptoms of depression, and the first two questions of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), assessing symptoms of anxiety [16]. The PHQ-4 was chosen because it is brief and easy to administer. It has been used to screen for mental health symptoms in adolescents with cancer [17], has good validity and reliability [18] and good sensitivity and specificity for detecting major depression (Richardson et al., 2010) and generalized anxiety disorder [19]. Electronic medical recordbased alerts notified staff when a patient was due for screening.

Patients completed paper forms manually, which were then scored by nursing staff and manually entered into the patient’s electronic medical record. Patients with a score >3 on either the first two questions assessing depressive symptoms or the last two questions assessing symptoms of anxiety were considered positive. Patients with a positive PHQ-4 screen were administered the PHQ-9 or GAD-7, depending on the area of concern. The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were scored by nursing staff. A patient was considered to have a positive screen on follow up measures if the total score was >10 on either measure or question nine was endorsed on the PHQ-9 indicating symptoms of suicidal ideation or self-harm. This workflow was seamlessly integrated into Epic’s medical record system by utilizing the “Best Practice Advisories (BPAs)” feature, which provided automated alerts to guide nurses through the screening process, ensuring timely follow-up actions and consistent application of evidence-based care protocols.

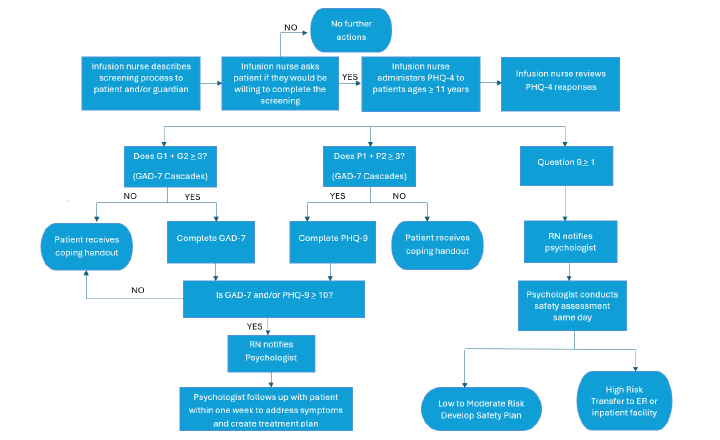

All patients screening positive on either of these measures received evaluation from the clinic-embedded pediatric psychologist within one week of the screen. All patients endorsing suicidal ideation or self-harm received an evaluation and safety assessment on the same day of the screen. All patients that had a positive screen on the PHQ-4 received handouts on coping with anxiety and depression. Non-verbal patients or those with developmental disabilities severely limiting cognition were excluded from the screening. Please see Figure 1 for a flow of the mental health screening workflow.

Figure 1:Mental health screening protocol.

Quality improvement initiative

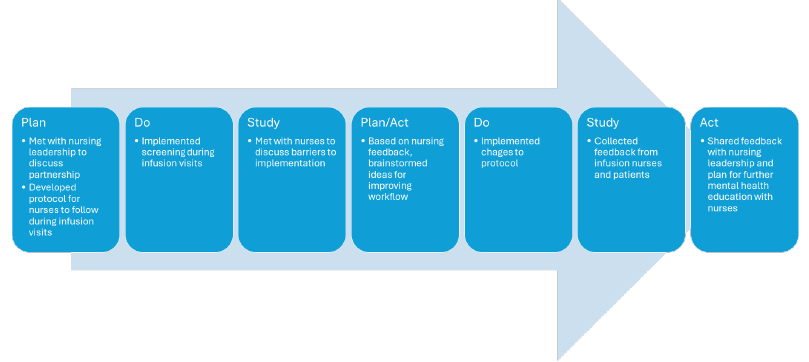

The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) method for process improvement was used to inform the planning and improvement strategies for this project. Prior to implementing the protocol, the clinic psychologist met with nursing leadership to discuss a partnership and develop a protocol for the screening. The protocol was then reviewed with nursing staff and implemented during infusion visits. Three months into the screening, the clinic psychologist met with nursing staff to discuss any barriers to implementation. Based on feedback, quality improvement investigators brainstormed ideas to improve workflow, including assisting with printing out measures during busy clinic times and administering the questionnaire during psychology visits for established patients. After these changes were implemented, quality improvement investigators gathered data from patients and nurses and shared feedback with nursing leadership to discuss a plan for further mental health education. See Figure 2 for a description of information regarding the steps of this quality improvement process.

Figure 2:Mental health screening quality improvement map.

Program Evaluation Questionnaires

Nursing feedback questionnaire

A six-item questionnaire was developed to assess nurses’ attitudes towards administering the PHQ-4 screening measure during infusion visits. The questionnaire was administered to nurses during a nursing meeting for feedback and consideration of any programmatic changes that might be necessary.

Patient feedback questionnaire

A ten-item questionnaire was developed to assess patient attitudes towards completing the PHQ-4 screening measure during infusion visits. The questionnaire was administered to patients who had completed a PHQ-4 screening during an infusion appointment.

Results

Out of the 480 screenings conducted over a three-year period, 37 adolescents with cancer and blood disorders ages 11-25 screened positive on the PHQ-4 (68 total positive screens; 14%). 18 patients screened positive on either the PHQ-9 (n= 12) or the GAD-7 (n=14); 8 patients had elevated scores on both measures. Of the 12 patients that completed the PHQ-9, two patients endorsed suicidal ideation. Twenty-five patients (68%) that screened positive had at least one visit with psychology, with twenty-one of those patients (57%) seen by psychology three or more times. Regarding race/ethnicity, 39% of all patients screened identified as Hispanic or Latino, with 43% of patients identifying as White, 19% identifying as Black, 16% identifying as Asian, 6% identifying as Multiracial, and 16% identifying as Other. The mean age of patients screened was 17.64 (range 12-24, SD=3.65). 50% of patients identified as female, 48% identified as male, and 2% identified as nonbinary. See Table 1 for demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1:Patient Demographics

Nursing Feedback

Data was obtained by six out of nine registered nurses who regularly administer infusions to patients within an oncology clinic. The nurses that did not complete the screen were asked to complete several times and did not for unknown reasons. The majority (67%) felt that nurses should ask patients about their mental health. However, most (67%) nurses surveyed reported that integrating the screener into their visit was somewhat difficult. There was a mix of responses regarding nurse’s comfort with asking questions about mental health, ranging from somewhat uncomfortable (67%) to mostly comfortable (33%). Half of the respondents had never given out the educational materials provided, while half reported that they disseminate this information sometimes. Most did not find the educational materials helpful. All but one nurse indicated they would be open to continuing education around mental health issues in pediatric patients. See Table 2 for a full list of results.

Table 2:Nurses Feedback.

Patient Feedback

A total of 19 patients with cancer or blood disorders completed a feedback questionnaire. During most of the PHQ-4 screenings, parents/caregivers were present (73%), but overall, patients reported that it did not affect their responses. However, one respondent indicated that having a caregiver present caused them to not endorse any problems even though they were experiencing symptoms. The survey inquired about mode of administration, with one respondent indicating that having an option to complete the questionnaire on their own led to a more honest report of symptoms, while another respondent indicated the opposite.

Table 3:Patient Feedback.

Most patients reported that questions about mental health should be asked during medical appointments (95%). They provided open-ended feedback that reflected this response, including themes that indicated recognition that mental health is part of one’s overall health and the importance of obtaining help when emotional concerns arise. Of the 19 patients surveyed, 12 were currently in therapy, six attended therapies in the past, and one had never attended therapy. Most patients reported that therapy was helpful to them (11). See Table 3 for patient feedback.

Discussion

A quality improvement effort that utilized collaboration between psychology and nursing was implemented to pilot mental health screening in a pediatric hematology/oncology clinic using the PHQ-4 to identify patients at high risk of distress. 14% of the screenings were positive on the PHQ-4, with 4% positive on the PHQ-9 or GAD-7. Only 26% of participants that screened positive on the short version also had a positive screening on the PHQ-9 or GAD-7, which is lower than other studies of children with chronic health conditions using similar measures [20]. Further, only 37 unique patients were identified during the screening out of 480 screenings conducted. Patient feedback questionnaires did not indicate that having a parent present or asking a nurse to read the questions aloud influenced most patients to answer questions differently. It is possible that the psychosocial support that patients were already receiving as part of their medical care contributed to lower symptoms of distress. However, research demonstrates that the level of behavioral health integration in medical clinics does not necessarily correlate with decreased distress [21]. Another possible explanation for the lower number of positive screenings is the timing of the administration. Completing the screening during infusion visits might have led to underreporting of symptoms as patients might not have been feeling well and thus were less aware of or less willing to disclose mental health symptoms.

Nursing Feedback

Feedback from nurses indicated overall support for asking questions regarding mental health during medical visits. Some nurses raised concerns regarding the feasibility of integrating the screening during the infusion visit, the ability to distribute educational materials, and comfort in asking questions about mental health. Importantly, partnering with nursing increased the volume of patients that would have otherwise not been screened by a mental health provider, ensuring that mental health screening was a part of the medical visit and not solely the role of psychosocial clinicians to identify concerns.

Patient Feedback

Patients endorsed that it is important to ask about mental health during medical visits, further highlighting the benefit of screening during routine medical care for hematology/oncology patients. According to Mental Health America Youth Data 2022, 15% of youth ages 12-17 report suffering from at least one major depressive episode in the past year and 11% suffer from severe major depression [22]. Notably, most of the sample surveyed was either currently enrolled in therapy or had attended therapy in the past, and most patients that had attended therapy described it as helpful, possibly skewing the results. This is in contrast with 2022 Mental Health America Youth Data report which found that 60% of youth with major depressive disorder do not receive any mental health treatment [22]. The contrast is likely due to the setting where the screening was administered, where patients can easily access psychotherapy services. In addition, patients could elect to decline the screening, so participants who completed the screen were more likely to have positive views about mental health.

Limitations and Future Directions

When considering future screening protocols for youth in pediatric hematology/oncology clinics, addressing implementation barriers is essential. Key priorities include enhancing provider training, securing institutional support and developing feasible screening processes. One limitation of this project was that parents and caregivers did not complete proxy reports of their child’s mental health. Parent/ caregiver proxy reports should be incorporated, as caregivers often identify mental health concerns that youth may not disclose [23]. Additionally, translating screening measures into multiple languages will improve accessibility across diverse populations.

Nursing staff are uniquely positioned to administer mental health screenings due to their close relationships with patients and families [13]. In this quality improvement initiative, while nurses received instructions for completing measures, they did not participate in any mental health education prior to administration of measures. Comprehensive education and support programs can increase nurses’ comfort with mental health screening tools and improve collaboration with mental health providers. Research shows that targeted educational programs effectively enhance mental health screening knowledge [24] and are crucial for preparing nurses to address the growing prevalence of mental health needs among patients with physical illness [25].

Conclusion

Assessing youth with evidence-based psychosocial screening methods assists in providing a comprehensive patient-first approach to treatment. Screening youth allows for the identification of psychosocial risk factors, increased access to mental health care providers by facilitating referrals to psychosocial services and improves overall treatment adherence and quality of life [2-4]. Research highlights that a key benefit of obtaining and accessing mental health support in a medical setting is that it reduces stigma for youth [26]. Implementing mental health care as a component of routine medical treatment helps overcome stigma and other barriers to seeking mental health care [27-35].

In this quality improvement initiative, hematology and oncology patients received mental health screening during infusion visits. Infusion nurses, in particular, develop strong bonds with patients and families through their consistent care during challenging treatments. Their established trust and frequent patient contact make them ideal candidates for administering screening measures.

These existing relationships create natural opportunities for mental health assessment while minimizing additional burden on patients and healthcare systems.

Author Note

Note

The corresponding author has moved to a new institution since the research was completed.

Acknowledgement

I would like to acknowledge Dr. Becky Lois who provided valuable contributions to the development of this quality improvement initiative as well as edits and revisions to the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Dr. Largen conceived of and designed the project, collected and analyzed data, and made significant contributions to the writing of the manuscript. Dr. Levy analyzed data and made significant contributions to the writing of the manuscript.

Statements and Declarations

Declaration of conflicts of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional review board approval

The screening was conducted as part of clinical care and the process was viewed via a program developmental/quality improvement framework. The Institutional Review Board at NYU Langone Health was consulted on this study and deemed that this study did not require formal IRB review or oversight.

Consent to participate

Authorization of informed consent was waived by New York University Langone Health Institutional Review Board as this research was conducted as part of routine clinical care and participants could choose to decline to participate at any time.

Data availability statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current quality improvement project are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Wiener L, Kazak AE, Noll RB, Patenaude AF, Kupst MJ (2015) Standards for the psychosocial care of children with cancer and their families: An introduction to the special issue. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62(Suppl 5): S419-S424.

- Barrera M, Alexander S, Shama W, Mills D, Desjardins L, et al. (2018) Perceived benefits of and barriers to psychosocial risk screening in pediatric oncology by health care providers. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 65(12): e27429.

- Kazak AE, Barakat LP, Askins MA, McCafferty M, Lattomus A, et al. (2017) Provider perspectives on the implementation of psychosocial risk screening in pediatric cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 42(6): 700-710.

- Kazak AE, Barakat LP, Ditaranto S, Biros D, Hwang WT, et al. (2011) Screening for psychosocial risk at pediatric cancer diagnosis: the psychosocial assessment tool. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology 33(4): 289-294.

- Kaul S, Avila JC, Mutambudzi M, Russell H, Kirchhoff AC, et al. (2017) Mental distress and health care use among survivors of adolescent and young adult cancer: A cross-sectional analysis of the national health interview survey. Cancer 123(5): 869-878.

- Henderson JR, Kiernan E, McNeer JL, Rodday AM, Spencer K, et al. (2018) Patient-Reported health-related quality-of-life assessment at the point-of-care with adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 7(1): 97-102.

- Kazak AE, Barakat LP, Hwang WT, Ditaranto S, Biros D, et al. (2011) Association of psychosocial risk screening in pediatric cancer with psychosocial services provided. Psycho-oncology 20(7): 715-723.

- Kazak AE, Deatrick JA, Scialla MA, Sandler E, Madden RE, et al. (2020) Implementation of family psychosocial risk assessment in pediatric cancer with the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT): Study protocol for a cluster-randomized comparative effectiveness trial. Implementation Science 15(1): 60.

- Scialla MA, Canter KS, Chen FF, Kolb EA, Sandler E, et al. (2018) Delivery of care consistent with the psychosocial standards in pediatric cancer: Current practices in the United States. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 65(3): e26869.

- Fagerlind H, Kettis Å, Glimelius B, Ring L (2013) Barriers against psychosocial communication: Oncologists’ Perceptions. J Clin Oncol 31(30): 3815-3822.

- Eilander M, De Wit M, Rotteveel J, Maas-van Schaaijk N, Roeleveld-Versteegh A, et al. (2016) Implementation of quality of life monitoring in Dutch routine care of adolescents with type 1 diabetes: Appreciated but difficult. Pediatric Diabetes 17(2): 112-119.

- Barrera M, Alexander S, Atenafu EG, Chung J, Hancock K, et al. (2020) Psychosocial screening and mental health in pediatric cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Health Psychology 39(5): 381-390.

- Granek L, Nakash O, Ariad S, Shapira S, Ben-David M (2019) Mental health distress: Oncology nurses' strategies and barriers in identifying distress in patients with cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 23(1): 43-51.

- Goltz HH, Major JE, Goffney J, Dunn MW, Latini D (2021) Collaboration between oncology social workers and nurses: A patient-centered interdisciplinary model of bladder cancer care. In Seminars in Oncology Nursing 37(1): 151114.

- Gruen LJ, Lee-Miller CA, Osman F, Parkes A (2023) Benefit of interdisciplinary care in resource identification in an adolescent and young adult oncology care model. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 12(5): 752-757.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B (2009) An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: The PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50(6): 613-621.

- Sebastian T, Close A, DeVeau C, Fessenden C, Braunreiter C (2024) Implementing mental health screening for adolescent hematology and oncology patients: A quality improvement initiative. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology 13(5): 768-775.

- Caro Fuentes S, Sanabria-Mazo JP (2024) A systematic review of the psychometric properties of the patient health questionnaire-4 in clinical and nonclinical populations. Journal of the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry 65(2): 178-194.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Löwe B (2007) Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine 146(5): 317-325.

- Watson SE, Spurling SE, Fieldhouse AM, Montgomery VL, Wintergerst KA (2020) Depression and anxiety screening in adolescents with diabetes. Clinical Pediatrics 59(4-5): 445-449.

- Urban TH, Stein CR, Mournet AM, Largen K, Wuckovich M, et al. (2022) Level of behavioral health integration and suicide risk screening results in pediatric ambulatory subspecialty care. General Hospital Psychiatry 75: 23-29.

- Reinert M, Fritze D, Nguyen T (2021) The state of mental health in America 2022. Mental Health America, Alexandria VA, USA.

- Barry-Menkhaus SA, Stoner AM, MacGregor KL, Soyka LA (2020) Special considerations in the systematic psychosocial screening of youth with type 1 diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(3): 299-310.

- Carrasco NM (2021) Educating nurses about postpartum depression. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing 50(5): S3-S4.

- Wynaden D (2010) There is no health without mental health: Are we educating Australian nurses to care for the health consumer of the 21st century? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 19(3): 203-209.

- Austin LJ, Browne RK, Carreiro M, Larson AG, Khreizat I, et al. (2024) It makes them want to suffer in silence rather than risk facing ridicule: Youth perspectives on mental health stigma. Youth & Society 57(1): 30-55.

- Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, et al. (2015) What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine 45(1): 11-27.

- Anderson LM, Papadakis JL, Vesco AT, Shapiro JB, Feldman MA, et al. (2020) Patient-Reported and parent proxy-reported outcomes in pediatric medical specialty clinical settings: A systematic review of implementation. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 45(3): 247-265.

- Kersun LS, Rourke MT, Mickley M, Kazak AE (2009) Screening for depression and anxiety in adolescent cancer patients. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology 31(11): 835-839.

- Klagholz SD, Ross A, Wehrlen L, Bedoya SZ, Wiener L, et al. (2018) Assessing the feasibility of an electronic patient-reported outcome (ePRO) collection system in caregivers of cancer patients. Psycho-oncology 27(4): 1350-1352.

- Polidoro Lima M, Osório FL (2014) Indicators of psychiatric disorders in different oncology specialties: A prevalence study. Journal of Oncology 2014: 350262.

- Marker AM, Patton SR, McDonough RJ, Feingold H, Simon L, et al. (2019) Implementing clinic-wide depression screening for pediatric diabetes: An initiative to improve healthcare processes. Pediatric Diabetes 20(7): 964-973.

- McCarthy MC, Wakefield CE, DeGraves S, Bowden M, Eyles D, et al. (2016) Feasibility of clinical psychosocial screening in pediatric oncology: Implementing the PAT2.0. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 34(5): 363-375.

- Mertens AC, Gilleland Marchak J (2015) Mental health status of adolescent cancer survivors. Clinical Oncology in Adolescents and Young Adults 5: 87-95.

- Steele AC, Mullins LL, Mullins AJ, Muriel AC (2015) Psychosocial interventions and therapeutic support as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 62 (Suppl 5): S585-S618.

© 2025. Kelsey Largen. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)