- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Research in Dentistry

Assessment of Taste Changes in Covid-19 Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study

Rucha Pandharipande1*, Mukta Motwani2, Smriti Golhar3, Apeksha Dhole4, Tapasya Karemore3, Sampada Kulkarni5 and Yash Sharma6

1Assistant Professor, Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, Ranjeet Deshmukh Dental College and Research Center, India

2Vice Dean (Clinical), Prof. & Head, Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, Ranjeet Deshmukh Dental College and Research Center, India

3Reader, Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, Ranjeet Deshmukh Dental College and Research Center, India

4Professor, Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, Ranjeet Deshmukh Dental College and Research Center, India

5Department of public health dentistry, Manipal college of Dental Sciences, India

6Intern, Ranjeet Deshmukh Dental College and Research Center, India

*Corresponding author: Rucha Pandharipande, Assistant Professor, Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, Ranjeet Deshmukh Dental College and Research Center, Nagpur, India

Submission: November 18, 2025;Published: December 01, 2025

ISSN:2637-7764Volume8 Issue5

Abstract

Background: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe

acute respiratory syndrome corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was reported by the World Health

Organization in 2019. Loss of taste and smell has been identified as the key COVID-19 predictors. The aim

of the present study is to evaluate prevalence of taste changes among Covid-19 patients and compare its

association with immunosuppressive therapy, hospitalization and presence of co-morbidities.

Material methods: In this cross-sectional study (questionnaire based) a total of 202 patients from

the Vidarbha region who were infected with COVID-19 were given a pre-validated questionnaire. The

questionnaire included brief history about various symptoms, taste changes during COVID-19 infection,

immunosuppressive therapy, hospitalization, presence of co-morbidities etc.

Result: It was found that 69.3% of patients experienced taste changes during Covid-19 infection and in

33.5% of patients’ loss of taste was the first symptom. There was a weak positive co-relation between

taste changes, immunosuppressive therapy, hospitalization and presence of co-morbidities in COVID-19

patients.

Conclusion: Taste changes were common among COVID-19 affected patients. Immunosuppressive

therapy, hospitalization and presence of co-morbidities do not seem to be linked with the taste changes

of Covid-19 infection.

Keywords:Altered taste; Ageusia; COVID-19

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) characterized by a variety of clinical manifestations such as fever, dry cough, shortness of breath (dyspnea), confusion, headache, sore throat, chest pain, diarrhea, nausea/vomiting, fatigue etc. [1,2]. Since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, reports from across the globe suggest that chemosensory loss is among the cardinal symptoms of active infection [3]. The occurrence of smell dysfunction in viral infections is not new in otolaryngology. Many viruses may lead to olfactory dysfunction through an inflammatory reaction of the nasal mucosa and the development of rhinorrhea; The most familiar agents being rhinovirus, parainfluenza Epstein-Barr virus [4]. The exact mechanism of taste change in COVID-19 is unknown. Some studies suggest that taste-related disturbances may be due to drugs prescribed for this viral illness, rather than from the actual infection while some say that taste disturbances reported by COVID patients may be the result of an actual impairment of gustatory abilities [5,6]. The aim of the present study is to evaluate prevalence of taste changes among Covid-19 patients in Vidarbha region and compare its association with immunosuppressive therapy, hospitalization and presence of co-morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes etc.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in Vidarbha region between May 2022 and September 2022. A sample sized 202 patients were selected to participate in the study. Our study employed a convenience sampling method, where patients were selected from the Outpatient Department (OPD) of Oral Medicine and Radiology. Convenience sampling was chosen due to practical considerations, such as accessibility and feasibility within the constraints of the study environment. Patients above 18 years of age with proven PCR or antigen tests minimum of two months before their inclusion in this study were considered. Patients with pregnancy, history of head and neck radiotherapy and/or active oncologic treatment, or xerostomia were excluded from the study. Ethical approval was obtained from institutional ethical committee of the institute (Approval no: IEC/VSPMDCRC/61/2022). A questionnaire was fabricated which included questions based on the symptoms of Covid-19 infection, taste loss, loss of smell, history of hospitalization, immunosuppressive therapy and presence of co-morbidities such as hypertension, diabetes etc. A pilot study was conducted to validate and standardize the self-reporting questionnaire used in our research. This pilot study involved a sample of 15 patients who were selected based on criteria like those used in the main study. To ensure the internal consistency of the questionnaire, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated based on the responses obtained from the pilot study participants. The calculated Cronbach’s alpha value for the questionnaire in our pilot study was [0.92]. The value suggested the extent to which the items in the questionnaire consistently measure the underlying construct of interest. The participants involved in the pilot study were not included in the final sample to avoid any overlap or influence on the results of the main study. The summaries of every participant were collected and statistically analyzed using SPSS2020 software. The association between two categorical variables was tested using the chi-square test and correlation was tested using spearman rank co-efficient.

Result

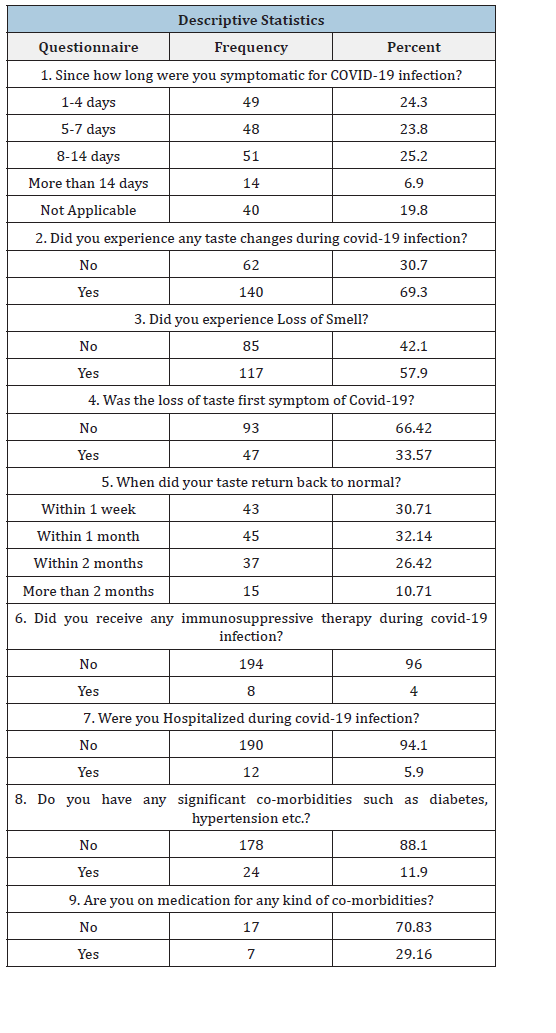

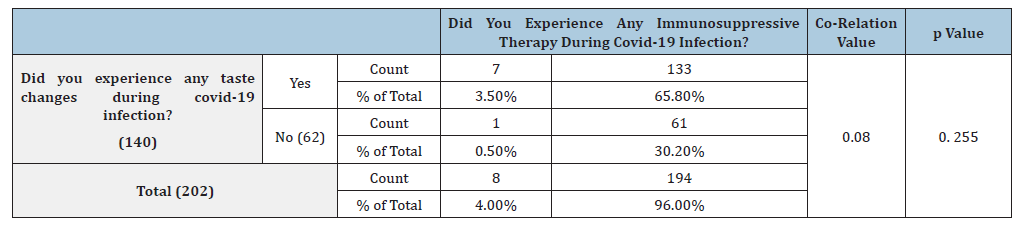

A total of 202 patients completed the study. The average age of the patients in the study ranged from 19 to 77 years. In the present study, 89 (44.1%) were females and 113(55.9%) were males. The descriptive statistics of the study depict that 24.3% patients were symptomatic for 1-4 days, 23.8% patients were symptomatic for 5-7 days, 25.2% patients were symptomatic for 8-14 days and rest of them were symptomatic for more than 14 days. About 69.3% of patients experience taste changes during the infection rest of them didn’t experience any taste changes. Out of 202 patients, 117 patients experienced loss of smell. In 33.57% of patients’ loss of taste was the first symptom of COVID-19 infection. 30.71% of patients reported that taste came back to normal within 1 week, for 32.14% of patients came back to normal within 1 month and for rest of them it took little, longer to recover (Table 1). Out of 140 patients who experienced taste changes, 7 patients had received immunosuppressive therapy while 133 patients didn’t receive any immunosuppressive therapy during Covid-19 infection. Similarly, the patients who did not experience any taste changes were asked the same, 1 patient confirmed undergoing immunosuppressant therapy while 61 patients didn’t receive any immunosuppressive therapy. This difference in the responses was found to be statistically non- significant (p=0.255). Spearman coefficient was found out to be 0.080 stating weak positive correlation between experience of taste changes and history of immunosuppressive therapy during covid infection (Table 2).

Table 1:Responses to the questionnaire.

Table 2:

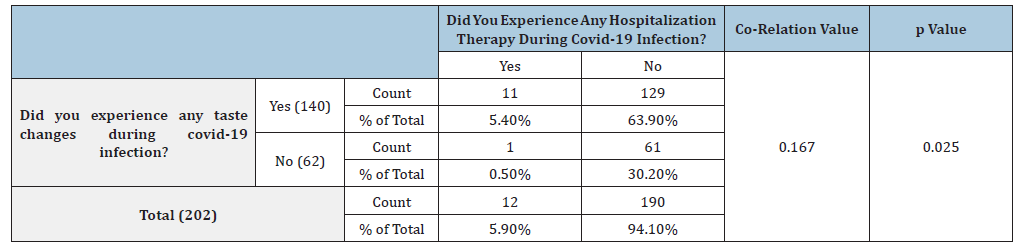

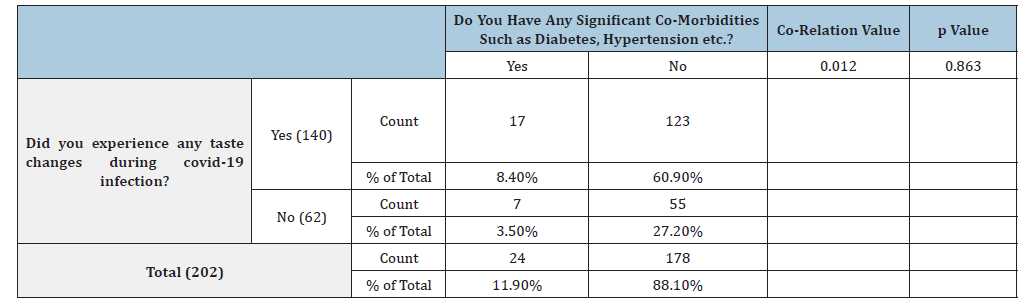

Out of the 140 patients with taste changes, 11 patients were hospitalized during covid infection and 129 did not undergo hospitalization. Out of the 62 patients with no taste changes only 12 were hospitalized for the treatment. This difference in hospital experiences of patients was statistically significant with the p Value of 0.025 (Table 3) The Spearman correlation test was used to check if the correlation can be established between taste changes and hospitalization, which was found out to be 0.167 showing a weak positive correlation. In the present study, 87.1% of patients didn’t have any significant co-morbidities such as diabetes, hypertension etc. and 96.5% of patients did not take any medications for such co-morbidities. Among patients who had taste changes during covid infection, 17 patients had significant co-morbidities such as diabetes and hypertension while 123 patients didn’t have any comorbidities. Among the patients who did not experience any taste changes, 7 patients had significant co-morbidities such as diabetes and hypertension, and 55 patients didn’t have any co-morbidities. This difference was not found out to be statistically significant (p=0.863) (Table 4). Spearman co-efficient value obtained was 0.012, showing a weak positive correlation between the symptom of taste change and medical history of other co-morbidities.

Table 3:Co-relation of taste changes and hospitalization therapy in COVID-19 patients.

Table 4:Co-relation of taste changes and co-morbidities in COVID-19 patients.

Discussion

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), which was reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 31 December 2019. The exact route of transmission is not yet fully solved. It is thought to be via respiratory droplets, like the spread of influenza virus. The spectrum of the illness of COVID-19 ranges from asymptomatic to critical respiratory failure and/ or multiorgan dysfunction; fortunately, most infections are not severe [7]. Taste and olfactory impairments, collectively known as chemosensory disorders, are alterations of the normal gustatory and olfactory functioning. There are various factors responsible for changes of taste which include a genetic factor, number of drugs (including some antimycotics, antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, immunosuppressants, neurologic medications and psychiatric drugs), trauma, surgeries (Partial or complete nerve transection, traction, or stretching), smoking, alcohol consumption, radiation therapies (e.g., in patients with head and neck cancers), nutritional deficiencies and viral infections. Viral infections which are responsible for taste changes include common cold (Rhinoviruses), influenza (Orthomyxoviridae), or hepatitis (Hepatoviruses). These cause nasal blockage, obstruction, and swelling of the mucosa generated by increased mucus production and changes in mucus composition. In most cases, taste and smell losses are temporary and they resolve once the symptoms disappear while some patients develop taste dysfunctions characterized by a complete loss or a reduced ability to detect and recognize taste stimuli [8,9].

Taste changes in covid-19 infection

It is assumed that severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus gains entry to cells via angiotensinconverting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptors. High expression of ACE2 is found in type II alveolar cells, macrophages, bronchial and tracheal epithelial cells and in the oral cavity, particularly on the tongue. The interaction between the viral spike protein (protein S) and the ACE2 receptor facilitates viral entry into cells. Given the presence of ACE2 in taste cells, it’s plausible that SARS-CoV-2 may directly affect these cells, leading to taste disturbances. Additionally, inflammatory responses triggered by viral infection, direct cell and/or neuronal injuries, dysregulation of ACE2 could contribute to alterations in taste perception [5]. In the present study 69.3% of patients experienced loss of taste and 59.7% of patients reported loss of smell. Cattaneo C et al. [10] conducted a case control study to evaluate changes in smell and taste perception related to COVID 19 infection. They tested 61 hospitalized patients positive for SARSCoV- 2 infection and 54 healthy individuals as controls. It was found that about 45% of patients self-reported complaints about or loss of either olfactory or gustatory functions [10]. In our study it was noted that in 33 % patients’ loss of taste was the first symptom of COVID-19 infection. Daniel H conducted a national survey in which a total of 220 people completed the survey, representing a wide geographic distribution across the United States. Of the 220 respondents, 93 (42%) were diagnosed with COVID-19, and 127 (58%) were not. A total of 37.7% of respondents reported changes in smell/taste as the initial presentation of their condition. Most but not all patients had other symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 at the time of chemosensory loss [11].

In contrast to a study conducted by Klein et al. [12], they found that smell and taste changes appeared on average around the fourth day after disease onset and were rarely the first symptoms to appear and were among the longest lasting. Taste durations had wide-ranging recovery times: 30% were resolved within 10 days, 20% were recovered within 60 days and 15% were unresolved even after 208 days [12]. PC Soares et al. [13] studied the characteristics of the sample of 31 participants with COVID19-related long-term taste impairment, and their capacity to quantify taste and rate their smell perception. They found that COVID-19 infection could trigger taste and smell disturbances that lasted as long as 24 months. COVID-19-related long-term taste impairment does not affect the four main taste perceptions (hyper-concentrated) equally. Previous diseases, medication use, and behavioral aspects are not linked to long term taste impairment [13,14].

Taste changes and Immunosuppressive therapy

The present study showed a weak positive co-relation between taste changes and immunosuppressive therapy. Literature review reveals no studies on effect of taste changes due to immunosuppressive therapy in Covid-19 infection.

Taste changes and hospitalization

The present study showed a weak positive co-relation between taste changes and hospitalization. This was found in accordance with a study conducted by PA Gusmao et al. [15] where they found taste disorders were associated with a lower risk of ICU admission and need for Mechanical ventilation, in addition to shorter hospital and ICU stay [15]. While a study conducted by Hussein RR studied oral changes in 210 Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients and found that 94.3% of the 210 patients who participated in the study had developed oral symptoms. Altered taste sensation was found among 56.2% of patients [16].

Taste changes and Co-morbidities

The present study showed a weak positive correlation between the symptoms of taste change and medical history of other co-morbidities. Similarly, a study was conducted Johnson BJ et al. [17] where they studied the patient factors such as age, gender and co-morbidities with taste changes. It was reported that patients with loss of smell had fewer high‐risk comorbidities [17]. However, a study was conducted in China in which total of 61,067 participants completed the questionnaire and 16,016 participants had preexisting diseases. The study showed that COVID-19 patients with high blood pressure, lung disease, or sinus problems, or neurological diseases exhibited worse self-reported smell loss, but no differences in the smell or taste recovery [18].

Limitations and future prospects

Self-reported taste and smell disturbances are not always reliable therefore further studies with sensory tests for olfaction and gustation are required. The sample size used in the present study couldn’t show any significant association between taste changes, immunosuppressive therapy, hospitalization and presence of co-morbidities therefore studies with large sample should be evaluated. Furthermore, the present study was based on past events, thus presenting them with a possibility of bias.

Conclusion

Loss of taste can be recognized as important symptoms of the COVID-19 infection. Patients may present with smell or taste loss before other symptoms and experience complete subjective loss of smell or taste. In most cases taste changes are reported back to normal within one month. Loss of taste can be used as a potential marker for viral infections. The findings of our study imply that taste changes could be due to Covid-19 infection by itself and not due to factors such as immunosuppressive therapy, hospitalization and presence of co-morbidities.

References

- Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC (2020) Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): A review. JAMA 324(8): 782-793.

- Sudre CH, Keshet A, Graham MS, Joshi AD, Shilo S, et al. (2021) Anosmia, ageusia and other COVID-19-like symptoms in association with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, across six national digital surveillance platforms: An observational study. Lancet Digit Health 3(9): 577-586.

- Dawson P, Rabold EM, Laws RL, Conners EE, Gharpure R, et al. (2021) Loss of taste and smell as distinguishing symptoms of coronavirus disease 2019. Clinical Infectious Diseases 72(4): 682-685.

- Dudine L, Canaletti C, Giudici F, Baroni V, Paris M (2021) Investigation on the loss of taste and smell and consequent psychological effects: A cross-sectional study on healthcare workers who contracted the COVID-19 infection. Frontiers in public health 9: 666442.

- Guan G, Rich AM, Polonowita A, Mei L (2022) Review of taste and taste disturbance in COVID-19 patients. The New Zealand Medical Journal 135(1549): 90-96.

- Lozada Nur F, Chainani Wu N, Fortuna G, Sroussi H (2020) Dysgeusia in COVID-19: Possible mechanisms and implications. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology 130(3): 344-346.

- Gonçalves LF, Gonzáles AI, Paiva KM, Patatt FS, Stolz JV, et al. (2020) Smell and taste alterations in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira 66(11): 1602-1608.

- Risso D, Drayna D, Morini G (2020) Alteration, reduction and taste loss: Main causes and potential implications on dietary habits. Nutrients 12(11): 3284.

- Su N, Ching V, Grushka M (2013) Taste disorders: A review. J Can Dent Assoc 79: d86.

- Cattaneo C, Pagliarini E, Mambrini SP, Tortorici E, Mené R, et al. (2022) Changes in smell and taste perception related to COVID-19 infection: A case-control study. Scientific Reports 12: 8192.

- Coelho DH, Kons ZA, Costanzo RM, Reiter ER (2020) Subjective changes in smell and taste during the covid-19 pandemic: A national survey-preliminary results. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 163(2): 302-306.

- Klein H, Asseo K, Karni N, Benjamini Y, Nir-Paz R, et al. (2021) Onset, duration and unresolved symptoms, including smell and taste changes, in mild COVID-19 infection: A cohort study in Israeli patients. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 27(5): 769-774.

- Soares PC, De Freitas PM, De Paula Eduardo C, Azevedo LH, De Freitas Sr PM, et al. (2023) COVID-19-related long-term taste impairment: Symptom length, related taste, smell disturbances, and sample characteristics. Cureus 15(4): e38055.

- Callejón-Leblic MA, Martín-Jiménez DI, Moreno-Luna R, Palacios-Garcia JM, Alvarez-Cendrero M, et al. (2022) Analysis of prevalence and predictive factors of long-lasting olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. Life 12(8): 1256.

- Gusmão PA, Roveda JR, Leite AS, Leite AS, Marinho CC (2023) Changes in olfaction and taste in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 and their relationship to patient evolution during hospitalization. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology 88(5): 75-82.

- Hussein RR, Ahmed E, Abou-Bakr A, El-Gawish AA, Ras ABE, et al. (2023) Oral changes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A cross-sectional multicentric study. Int J Dent 2023: 3002034.

- Johnson BJ, Salonen B, O Byrne TJ, Choby G, Ganesh R, et al. (2022) Patient factors associated with COVID‐19 loss of taste or smell patient factors in smell/taste loss COVID‐ Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 7(6): 1688-1694.

- Chen J, Mi B, Yan M, Wang Y, Zhu K, et al. (2023) The effects of comorbidities on the change of taste and smell in COVID‐19 patients. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 8(1): 25-33.

© 2025 Rucha Pandharipande. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)