- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy

Substrate Management Effects on Biomass Yield and Cannabinoid Profile in Cannabis Sativa L. under Controlled Cultivation in Argentina

Voisín Axel1, Ajamil Tomas1, Urbisaglia Franco1, Colmann Lerner Esteban2,3, Aranda M Oswaldo2, Weber Christian1,4*

1Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias y Forestales, UNLP, Argentina

2Facultad de Ciencias Exactas, UNLP, Argentina

3Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas (CONICET), Argentina

4Comisión de Investigaciones Científicas (CICPBA), Argentina

*Corresponding author:Weber Christian, Comisión de Investigaciones Científicas (CICPBA), Argentina

Submission: December 12, 2025;Published: January 07, 2026

ISSN 2637-7659Volume15 Issue 4

abstract

Cannabis sativa L. has recently been legalized for industrial and medicinal production in Argentina; however, agronomic information relevant to horticultural systems in general and to the La Plata Horticultural Belt (CHP) in particular, remains limited. Substrate selection is a key factor influencing vegetative growth, biomass accumulation and cannabinoid synthesis. We conducted a factorial randomized experiment using three C. sativa varieties grown in three substrates: (i) conventional horticultural soil, (ii) organic horticultural soil, and (iii) a commercial peat-based substrate. Plants were cultivated under controlled greenhouse conditions with standardized irrigation and fertigation. Biomass yield, Harvest Index (HI), nitrogen status (SPAD), and cannabinoid composition (THC, THCA, CBD, CBDA, CBN) were assessed. Cannabinoid quantification was performed via HPLC-UV. Variety had a significant effect on biomass production and cannabinoid profiles, whereas substrate type did not significantly influence these variables. Variety B exhibited the highest total dry biomass (75.1g plant⁻¹), flower biomass (27.8g plant⁻¹), and HI (0.38). Substrate did affect nitrogen status, with the peat-based substrate showing the lowest SPAD values. Cannabinoid profiles were strongly genotype-dependent: Variety A accumulated higher CBD/CBDA, Variety B was THC/THCA-dominant and Variety C displayed an intermediate chemotype characterized by elevated CBN. Overall, genetic background was the primary determinant of yield and cannabinoid composition, outweighing substrate effects. These findings underscore the critical role of variety selection in optimizing cannabinoid production under controlled environments and indicate that conventional and organic horticultural soils may serve as viable alternatives to commercial peat-based substrates.

Keywords:Cannabis sativa; Substrate management; Biomass yield; Cannabinoids; Horticultural systems; Argentina

Introduction

Cannabis sativa L. is an annual, dioecious, short-day herbaceous species belonging to the family Cannabaceae. Archaeobotanical evidence indicates that the species has been cultivated for more than 6000 years [1], with origins generally traced to the northeastern Tibetan Plateau, where early domestication likely occurred for the extraction of bast fiber, seed oil and resin produced in epidermal glandular trichomes [2,3]. Today, hemp and medicinal cannabis represent an emerging sector in global agricultural markets. France and China constitute major producers, whereas the Czech Republic is a primary importer [4]. In Argentina, reliable estimates of cultivated area, crop yields and economic indicators remain unavailable due to the recent legalization of industrial cannabis production under Law No. 27.669, enacted on 20 January 2023 [5]. Advances in plant breeding have enabled the development and differentiation of cultivars suited to various production systems-including medicinal, fiber, grain and dual-purpose types-and have facilitated the selection of chemotypes with distinct cannabinoid biosynthetic profiles and psychoactive properties [4,6]. The pharmacological activity of cannabis is attributed to a complex mixture of secondary metabolites, including cannabinoids, terpenes, and flavonoids, predominantly accumulated in female inflorescences [7,8]. Δ⁹- Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD) are the most abundant cannabinoids; while THC is psychoactive, CBD exhibits negligible psychoactivity and demonstrates therapeutic potential for modulating pain and inflammation [9].

Soil fertility and mineral nutrition strongly influence cannabis growth and metabolite production. Nitrogen (N) supplementation typically enhances vegetative development, as demonstrated by [10], who reported increases in plant height and biomass under N fertilization. However, the relationship between N availability, biomass production and cannabinoid concentration is inconsistent. Some studies report positive biomass responses without corresponding changes in cannabinoid content [11], whereas others indicate that N deficiency can increase cannabinoid and terpenoid concentrations despite reducing overall biomass [12]. Additional evidence shows that high N regimes can decrease THC content in leaves [13] and that excessive fertilization during vegetative growth may reduce floral yield and THC concentration [12].

Medicinal cannabis is commonly cultivated in environmentally controlled greenhouses or growth rooms, which may permit up to four harvests per year, compared to a single annual harvest in openfield systems [14]. Although controlled environments improve quality standardization, they impose high production costs and substantial ecological impacts due to intensive energy use associated with lighting, climate control, and other technological inputs. Outdoor cultivation substantially reduces energy requirements. Cannabis sativa generally requires a photoperiod of 12-14 hours [15] and annual water inputs of approximately 250-350mm [16]. Optimal climatic conditions include temperate environments (19- 25 °C), high relative humidity, and diurnal temperatures near 20- 25 °C with nocturnal minima of 13-17 °C. Loam or silt-loam soils rich in organic matter, well-drained, and with a pH of 5.5-7.0 are considered ideal; the species is sensitive to salinity and exhibits poor performance in clay-rich soils [17,18].

The selection of an appropriate substrate is therefore fundamental for providing adequate physical and chemical conditions to support root development and optimize plant performance. Substrates are defined as synthetic, mineral, ecological, or organic solid materials used to fill containers and provide a rooting environment with physicochemical and biological functions [19]. Porous substrates have been associated with increases in inflorescence biomass and THC content [20], while lightweight, aerated substrates promote lateral root proliferation and enhance water and nutrient uptake [21]. Peat-based mixtures are widely used due to their high waterholding capacity, though amendments are often required to correct their naturally acidic pH. In the floricultural-horticultural region of La Plata, known as La Plata Horticultural Belt (CHP) (Buenos Aires Province, Argentina), one of the main horticultural areas in South America [22], soil management practices have traditionally been shaped by local customs. In the absence of technical guidance, soils managed by smallholder producers often exhibit degradation due to inappropriate fertilization regimes, imbalanced nutrient availability (e.g., excessive P and Na), and recurrent application of corrective amendments at unsuitable doses. Irrigation with bicarbonate-rich sodium waters has caused salinization and sodification, especially under protected cultivation. Excessive tillage with equipment detrimental to soil structure has further degraded physical properties, impairing root growth and restricting water and air movement [23].

The renewed interest in cannabis production is partly driven by its favorable ecological and agronomic characteristics [24]. Beyond its multifunctional applications, cannabis exhibits low allelopathic activity [25], and certain root-exuded compounds may suppress competing weeds, thereby reducing herbicide requirements under intensive systems. Several authors argue that cannabis can be grown with minimal pesticide use and with comparatively low external inputs [26]. These attributes raise the possibility of integrating cannabis into long-established horticultural systems in the peri-urban horticultural belt of La Plata (CHP) either as a transitional crop toward full cannabiculture or as a diversification strategy capable of generating both environmental co-benefits and additional income for producers. To that end, the present study evaluates how substrates derived from conventional and organic horticultural systems influence yield and quality in Cannabis sativa L., thereby elucidating how soil-use history affects key agronomic and phytochemical variables. Taken together, these agronomic, environmental, and socio-productive considerations underscore the need to understand how substrate properties shaped by different horticultural management histories influence cannabis performance. In particular, there is limited evidence on how substrates originating from conventional and organic systems affect growth, biomass allocation, floral yield, and cannabinoid profiles, and how these responses compare with those observed in widely used commercial peat-based substrates. The relative importance of substrate effects versus cultivar-specific traits also remains insufficiently characterized, especially in regions where cannabis production is emerging and growers rely on locally available materials. In this context, the present study investigates how substrates derived from conventional and organic horticultural systems influence key agronomic and phytochemical variables in Cannabis sativa L. Specifically, we assess growth parameters, yield components, and cannabinoid composition in three cultivars grown under controlled conditions and compare their performance against that obtained using a commercial peat-based substrate. This approach provides an empirical basis for evaluating the potential integration of cannabis into peri-urban horticultural systems and for guiding substrate selection in newly developing production regions.

Materials and Methods

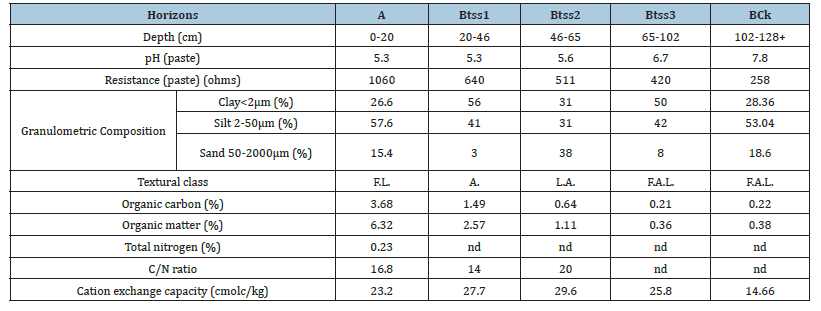

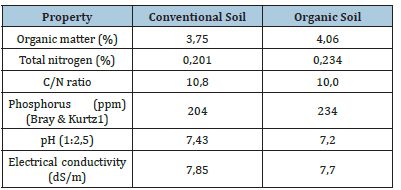

The experiment was conducted at the Faculty of Agricultural and Forest Sciences of the National University of La Plata, in La Plata County, Buenos Aires Province. The trial was established using Cannabis sativa L. clones from three different varieties (A, B, and C). At the beginning of the experiment, plants were approximately 15cm tall, free of pests and diseases, and transplanted into 20-L pots. Three different substrates were used: the first was extracted from a greenhouse soil under conventional horticultural production (1) -high inputs uses; and the second from an organic horticultural greenhouse; (2) both located at the CHP. As a control, a commercial peat-based substrate (Sphagnum sp.) Terrafertil® Light Mix; (3) was included. After transplanting, an apical pruning was performed to homogenize plant height. A completely randomized factorial design was used, with three Cannabis sativa L. varieties, three substrates, and three replicates (Figure 1). Substrates 1 and 2 correspond to soils classified as Vertic Argiudolls, belonging to the Arturo Seguí Series [27]. These soils are well supplied with organic matter, exhibit acidic pH that becomes alkaline at depth due to dissolved salts in groundwater, are moderately supplied with N, and are rich in silt and clay, resulting in internal drainage limitations caused by the slow permeability of the B horizon [27] (Table 1).

Figure 1:Pots with 3 C. sativa clones and their repetitions.

Table 1:Typical soil profile of the series.

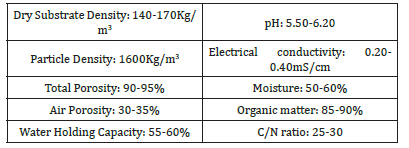

Substrate 3, used as a control, consists of a mixture of sphagnum peat, pine bark compost, perlite, vermiculite, pH adjusters, fertilizers, and wetting agents, which confer the physicochemical properties described in Table 2 & 3. The cultivation room had walls made of solid material combined with transparent glass covered with 100-μm agro-plastic film to allow complete darkening and thus control the photoperiod. The cultivation area was 15m². During the vegetative phase, plants were exposed to 18h of light for approximately two months. During the reproductive phase (9 weeks), they were exposed to 12h of light. Illumination was provided by 420-W LED panels with a CRI >95% and a PPF of 2.5μmol/J. Temperature and humidity were controlled using an air-conditioning system, maintaining relative humidity around 50% (±5%) and air temperature at 24 °C (±2 °C). Ambient CO₂ concentration (always within atmospheric, non-limiting values), temperature, and relative humidity were monitored using a CO₂ sensor. Irrigation was applied manually every other day with dechlorinated water to maintain field capacity. Fertigation was applied uniformly to all treatments every three days using an acidreaction (pH 4.5 at 15% solution) water-soluble fertilizer containing N, Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K), Sulfur (S), and Magnesium (Mg) in a 15-10-15 ratio, as well as EDTA-chelated micronutrients, dosed at 1g·L⁻¹ according to label instructions. To compare plant nitrogen status across treatments, chlorophyll content was measured with a chlorophyll meter at three developmental stages: vegetative growth, flowering, and harvest maturity.

Table 2:Physicochemical properties of the soils used as substrate 1 and 2..

Table 3:Physicochemical properties of the substrate 3.

To determine harvest maturity, glandular trichomes on inflorescences were observed using a handheld 3.5× magnifying lens. At maturity, trichomes acquire an opaque-white appearance [28] (Figure 2). Once plants reached this stage, they were harvested manually by cutting at the base with pruning shears and placing the plant material into pre-labeled paper bags. Samples underwent two drying phases: the first in a dark chamber at 24 °C and 40% relative humidity for 15 days; the second in a laboratory oven at 60 °C until constant weight. Dried samples were processed to separate the target material-dried flowers-from branches. Dried flowers were stored in pre-labeled transparent nylon bags and weighed using a precision scale (0.1-200g capacity) to determine variables such as Total Biomass (TB), inflorescence biomass, Harvest Index (HI), and Phyto cannabinoid profile. Cannabinoid Extraction (THC, CBD, cannabinol [CBN], tetra hydro cannabinolic acid [THC-A], and cannabidiolic acid [CBD-A]) were performed at the Faculty of Exact Sciences, National University of La Plata. For each sample, 500mg of homogenized material was extracted in 10mL of methanol. Extraction was assisted with an ultrasonic bath for 30min, followed by centrifugation at 10,000rpm for 5min. Samples were then filtered through a 0.22-μm nylon syringe filter (13mm diameter). The resulting extract was diluted 1:10 prior to analysis by High- Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection at 228nm. Data for all variables were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANVA) using Info stat software (Di Rienzo et al. 2020).

Figure 2:Clear capitate-stalked glandular trichomes present in the floral tissue of mature Cannabis sativa L.

Result

Total biomass

No significant interaction was found between Variety × Substrate for total biomass (p=0.068). Significant differences were detected among varieties (p=0.056). Variety B exhibited the highest total biomass (75.07 g·plant⁻¹), differing statistically from Variety A. Variety A produced 30% less biomass than varieties B and C (Figure 3). No significant differences were observed among substrates (p=0.308), with an overall mean of 66.52g·plant⁻¹ (Figure 4).

Figure 3:Total dry biomass for the A, B and C varieties. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p≤0.05).

Figure 4:Total dry biomass as affected by substrate type. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p≤0.05).

Flower biomass

Figure 5:Dry flower biomass obtained for each variety (A, B and C). Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p≤0.05).

No significant Variety × Substrate interaction was detected for flower biomass (p=0.220). As with total biomass, significant differences were found among varieties (p=0.0002). Variety B produced the highest flower biomass (27.80g·plant⁻¹), differing statistically from varieties A and C. Under the same conditions, Variety B produced 122% and 70% more flowers than varieties A and C, respectively (Figure 5). No significant differences were detected among substrates (p=0.390), with an average flower biomass of 18.9 g·plant⁻¹ (Figure 6).

Figure 6:Dry flower biomass as affected by different substrates. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p≤0.05).

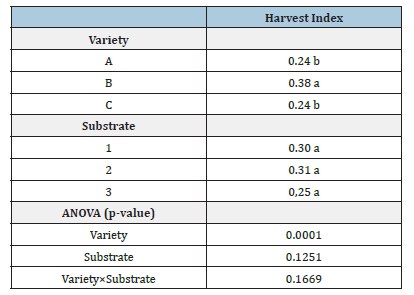

Harvest index

No significant interactions were detected for Variety × Substrate or for substrate alone. However, significant differences were found among varieties. Variety B had the highest HI, differing statistically from varieties A and C (Table 4).

Table 4:Harvest index of three Cannabis sativa L. varieties grown in three different substrates (1: conventional soil, 2: organic soil and 3: peat). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences according to Fisher’s LSD test (p≤0.05).

Nitrogen status

No significant Variety × Substrate interaction was observed at any evaluation stage. No differences were found among varieties (Figure 7). However, significant differences were detected among substrates (Figure 8). At all stages, the peat-based control substrate showed the lowest SPAD values.

Figure 7:SPAD units across growth stages-vegetative-flowering-harvest- for varieties A, B and C. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p≤0.05).

Figure 8:SPAD units for the varieties used across growth stages as affected by substrate types. Different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences (p≤0.05).

Cannabinoid concentration

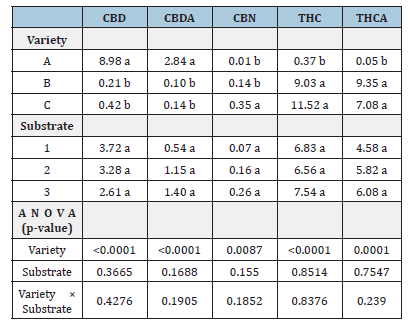

No significant Variety × Substrate interactions were detected for any cannabinoid (Table 5). Likewise, no significant substrate effects were detected. Variety had a significant effect on cannabinoid composition (Table 5).

Table 5:Cannabinoid concentrations, expressed as % w/w, for three Cannabis sativa L. varieties (A, B, and C) grown in three different substrates (1: conventional soil, 2: organic soil and 3: peat). Within each column, different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences according to Fisher’s LSD test (p≤0.05).

Cannabinoid extraction results showed that Variety A had predominately CBD and CBDA, with minimal THC and THCA. Variety B exhibited high THC and THCA concentrations and low CBD and CBDA. Variety C displayed an intermediate profile, with high THC and THCA and elevated CBN.

Discussion

Regarding total biomass, Variety B produced 75.07g·plant⁻¹, significantly outperforming varieties A and C (30% difference). For flower biomass, Variety B again exceeded the other varieties, producing 27.80g·plant⁻¹-121.68% more than Variety A and 69.6% more than Variety C. Variety A showed the lowest yields in both total and flower biomass, while Variety C displayed intermediate values. Variety B also exhibited the highest HI, whereas varieties A and C showed lower values, with Variety A being the lowest (0.18). These results contrast with previous studies, particularly regarding N effects on biomass and cannabinoids [11]. Reported increased biomass with rising N levels but no correlation between N availability and cannabinoid concentrations. In contrast, in our study, Variety B exhibited high total and flower biomass did not yet show the highest SPAD values, suggesting that cannabinoid production may have been more influenced by genetic factors than N status [12]. Noted that higher cannabinoid concentrations occurred under N deficiency, while biomass increased under sufficient N.

However, in our experiment, despite substrate showing no significant effect on cannabinoids, Variety B accumulated high THC and THCA levels without exhibiting N deficiency-implying genetics played a greater role in cannabinoid accumulation than substrate N availability. Our findings align with [13], who reported reduced THC in leaves under high N regimes. Although Variety B had the highest biomass yields, it did not show the highest cannabinoid concentrations, reinforcing the idea that the nitrogen–cannabinoid relationship may not be as direct as previously proposed. Moreover, our results differ from [10], who reported that N status influenced both biomass and cannabinoids. In this study, variety–substrate combinations produced significant variation in biomass and flower production, but without a clear correlation with N status. Overall, our results indicate that while N status influenced some aspects of crop performance, genetic factors played a central role in determining biomass production and cannabinoid profiles.

Conclusion

Genetic differences among the evaluated varieties had a significantly greater influence on biomass production and HI than substrate type. Similarly, cannabinoid concentrations were not determined by substrate characteristics but were instead governed by genetic attributes of the varieties.

Final Considerations

Although substrates did not significantly affect the evaluated variables, environmental conditions within the controlledenvironment facility (temperature, humidity, photoperiod, etc.) may have influenced the observed results. Additionally, substrate interactions with other factors may vary with production scale, particularly since plants were grown in confined containers. This highlights the need for further studies encompassing a broader range of environmental and soil conditions. More robust conclusions could be obtained by increasing the number of evaluated varieties and substrates, as well as examining additional nutritional factors, such as nitrogen, which may influence plant performance and chemical quality under real production conditions.

References

- Li HL (1974) An archeological and historical account of Cannabis in China. Economic Botany 28(4): 437-448.

- Small E (1975) Morphological variation of achenes of Cannabis. Can J Bot 53(10): 978-987.

- Clarke RC, Merlin MD (2013) Cannabis: Evolution and ethnobotany. University of California Press, Berkeley, California, USA.

- (2022) Secretariat of agriculture, livestock and fisheries (SAGyP). Report on the production and market of industrial and medicinal cannabis, Argentina.

- (2023) Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina, 27: 669.

- Small E (2015) Evolution and classification of Cannabis sativa in relation to human utilization. Annu Rev Plant Biol 66: 89-112.

- Hanuš LO, Meyer SM, Muñoz E, Taglialatela-Scafati O, Appendino G (2016) Phytocannabinoids: A unified critical inventory. Nat Prod Rep 33(12): 1357-1392.

- Russo EB (2011) Taming THC: Potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects. Br J Pharmacol 163(7): 1344-1364.

- Zuardi AW (2008) Cannabidiol: From an inactive cannabinoid to a drug with broad therapeutic potential. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 30(3): 271-280.

- Papastylianou P, Kakabouki I, Travlos I (2018) Effect of nitrogen fertilization on growth and yield of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Not Bot Horti Agrobo 46(1): 197-201.

- Bevan L, Jones M, Zheng Y (2021) Optimization of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium for soilless production of Cannabis sativa in the flowering stage using response surface analysis. Front Plant Sci 12: 2587.

- Saloner A, Bernstein N (2021) Nitrogen supply affects cannabinoid and terpene production in medical cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.). Ind Crops Prod 167: 113516.

- Bócsa I, Máthé P, Hangyel L (1997) Effect of nitrogen on Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content in hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) J Int Hemp Assoc 4(2): 67-69.

- Potter DJ (2014) A review of the cultivation and processing of cannabis (Cannabis sativa L.) for production of prescription medicines in the UK. Drug Test Anal 6(1-2): 31-38.

- Zhang M, Anderson SL, Brym ZT, Pearson BJ (2021) Photoperiodic flowering response of essential oil, grain and fiber hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Front Plant Sci 12: 694153.

- Herppich WB, Gusovius HJ, Flemming I, Drastig K (2020) Effects of drought and heat on photosynthetic performance, water use and yield of two selected fiber hemp cultivars. Agronomy 10: 1361.

- Lata H, Chandra S, ElSohly MA (2017) Cannabis sativa L.: Botany and horticulture. In: Janick J (Ed.), Horticultural Reviews, Wiley, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, pp. 1-49.

- McPartland JM (2014) Cannabis agronomy: Soil, field performance, and nutrition. In: Pertwee RG (Ed.), Handbook of Cannabis. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 339-66.

- Bunt AC (1988) Media and mixes for container-grown plants. 2nd (edn), Unwin Hyman, London, UK.

- McPartland JM (2018) Cannabis systematics at the levels of family, genus and species. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res 3(1): 203-212.

- Mechoulam R (2016) Cannabis-the Israeli perspective. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol 27(3): 181-187.

- Baldini C, Marasas ME, Tittonell P, Drozd AA (2022) Urban, periurban and horticultural landscapes: Conflict and sustainable planning in La Plata district, Argentina. Land Use Policy 117: 106120.

- García M, Vázquez S (2008) Manual para el manejo sustentable de suelos hortícolas del periurbano de La Plata.

- Cosentino SL, Testa G, Scordia D, Copani V (2012) Sowing time and prediction of flowering in Cannabis sativa L. Ind Crops Prod 37(1): 20-28.

- Pudełko K, Majchrzak L, Narożna D (2014) Allelopathic effect of fiber hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) on monocot and dicot plant species. Ind Crops Prod 56: 191-199.

- Struik PC, Amaducci S, Bullard MJ, Stutterheim NC, Venturi G, et al. (2000) Agronomy of fiber hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) in Europe. Ind Crops Prod 11(2-3): 107-118.

- Hurtado MA, Giménez JE, Cabral MG (2006) Análisis ambiental del partido de La Plata. Aportes al ordenamiento territorial. UNLP, La Plata, Argentina.

- Potter DJ (2009) The propagation, characterization and optimization of Cannabis sativa L. as a Phytopharmaceutical. King’s College, London, UK.

© 2026 Weber Christian. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)