- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy

Transition from the Agricultural Extension Model to Local Devices for Transdisciplinary Co-Innovation

Luis L Vázquez*

Associate Research in Cuba, Latín American Center for Agroecological Research (CELIA), Cuba

*Corresponding author:Luis L Vázquez, Associate Research in Cuba, Latín American Center for Agroecological Research (CELIA), Cuba

Submission: November 24, 2025;Published: December 17, 2025

ISSN 2637-7659Volume15 Issue 4

Summary

Conventional agricultural extension is in decline due to the demand for contextualizing training and technological innovation during the transition to sustainable local food systems. This short article was prepared with the aim of raising awareness about institutional innovation to adopt adaptive transdisciplinary co-innovation at the scale of local food systems. It was developed as a critical reflection based on personal experiences, supported by selected references. The first part analyzes the decline of the conventional agricultural extension model, before addressing the transition to decentralized co-innovation. The second part of the article delves into territorial co-innovation for the transition to sustainable local food systems and emphasizes the value of local knowledge.

Keywords:Technological innovation; Institutional innovation; Local food systems; Sustainable food; Local knowledge

Introduction

Conventional agricultural extension, as a vertical model of technology transfer from scientific centers, is in decline due to the demand to contextualize training and technological innovation during the transition towards sustainable local food systems, under the perspective of Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Agroecological Knowledge Management (AKM), among other methodological proposals that represent a challenge for institutional innovation in scientific centers and local technical service entities. In this field, territorial socio-technical innovations become relevant in changes that involve not only technical aspects but also organizational dynamics and collective action in the territory [1,2]; the territory is seen as a socially constructed space where diverse actors interact, including farmers, institutions and communities [3,4]. Technological innovation takes on greater significance when considering the “One Health” approach, because vertical specialization, which fragments scientific interdisciplinarity, leads to agricultural, environmental, food, health, education and social sciences being disconnected, causing unsustainability in the application of their scientific products within the food system. It is recognized that there are many ways to access knowledge to achieve the sustainable transformation of food systems, all of them equally valuable and necessary. These forms of knowledge are inherently intercultural, exchangeable, dynamic and fluid. They include scientific knowledge, indigenous knowledge, peasant and traditional knowledge, knowledge from civil society and community organizations, lived experiences and other forms of knowledge that form the foundation of the core understanding of agroecology, regenerative agricultural practices and indigenous food customs [5].

New social practices generate, but at the same time require, new knowledges and understandings, which have specific demands: their own complex and dynamic nature requires continuous learning, so that individuals as well as communities, companies, governmental institutions, cultural organizations, etc., develop skills to face the new challenges of the knowledge society and prepare for a more positive integration into the new global scenario [6]. It is acknowledged that approaches to enable transitions should be based on the principles of participation, using a bottom-up rather than a top-down approach. The voices and priorities of food producers, especially young people, women, indigenous peoples, and other local communities, should guide transitions and the actions taken to drive them [7]. To prepare this short article, it was assumed that agricultural and livestock production needs to move towards sustainable food systems, through the integration of training and technological innovation based on processes adapted to the characteristics of different contexts. Specifically, this short article aims to raise awareness about institutional innovation to adopt adaptive transdisciplinary co-innovation.

Material and Methods

This short article was developed as a critical reflection based on personal experiences, supported by selected references, with the purpose of raising awareness about the need to move toward contextualized innovation systems as a socio-technical scientific process to achieve sustainable food. The article begins by briefly analyzing the legacy of the vertical model of agricultural extension that characterizes conventional technological innovation, in contrast with developments in agroecological transition as contextual transdisciplinary processes. Subsequently, the need to advance toward a prospect of decentralized co-innovation is justified. For the purposes of drafting this article, the analysis of knowledge management and innovation was based on the experience of having participated, since the 1970s, first in agricultural extension processes; later, in facilitating the agroecological transition in territories of Cuba.

Descendants of the vertical agrarian extension model

Most of the research centers that contribute to food production are specialized institutions, whose scientific results constitute technological innovations on specific processes and products, which are introduced into agricultural and livestock production in a vertical manner, through extension mechanisms, technical services, input markets, among others. Although this system works relatively well for conventional agriculture, the transition toward sustainable food requires adapted technologies, because production systems are being transformed into integrated agroecosystems of agriculture, livestock and forestry, whose outputs are offered in the same context. It is very evident that the closed innovation model, consolidated during the conventional agriculture and livestock approach, led to hyper specialization in food-related sciences, to the point that comprehensive research centers are subdivided into specialties; furthermore, new specialized centers are even created, also structured by specialties. This fragmentation, which contributed to research with an analytical approach to obtain new technological products, led to the establishment of vertical agricultural extension systems to implement technologies with a certain degree of difficulty in their practical application, a characteristic that eroded comprehensiveness, compatibility and potential synergies in the applicability of the technologies for products and processes generated.

In fact, at the international level, there is a consensus that the processes of “modernizing agriculture” and implementing the techniques of the “Green Revolution” were carried out with strong institutional support, embodied in agricultural research and extension services well-endowed with economic and human resources, forming a model of vertical and one-way research and technology transfer, which has been heavily criticized since the 1970s [8,9]. The classic form of intervention in many countries has materialized in the creation of public research and extension institutions. Due to their operation under a centralized and linear model, this type of institution has been subject to multiple criticisms, questioning their effectiveness and efficiency in the generation, but especially in the dissemination of knowledge. The main criticism revolves around their linear vision of the technology transfer process, in which basic research progresses to applied research, then to technological development, from there to production, and subsequently to commercialization, with a defined and limited role for each of the different actors: universities and research centers, extension institutes, advisors and consultants, companies, and organizations, among others [10].

The compartmentalization of human knowledge and hyper specialization are nothing more than a product of industrial society; however, since the second half of the 20th century, we have been witnessing the emergence of a multitude of theoretical approaches and methods of a multidisciplinary and cross-cutting nature, in light of the universal assumption that to address the challenges we face, a holistic and systemic vision is necessary to understand these phenomena in all their complexity [11]. In the current situation, it is necessary for the generation of knowledge to start from more critical, more human, more contextual concepts, recognizing that when transmitting knowledge generated in a certain place, one must, on the one hand, consider the social reality where this knowledge will be used [10]. In other words, the central concern today is the sustainability of agriculture, conceived as a system that is economic, social, and ecological [12].

Agroecology is a complex socio-technical, organizational, and contextual/territorial phenomenon, which in particular suggests a broad approach that allows understanding (considering) agricultural action in holistic terms, proposing that the contemporary problem of production has evolved from a purely technical dimension to a more sociotechnical dimension, where social, economic, political and ecosystem aspects are present and are part of the situation [13].

The practices associated with agroecology have a transformative nature that involves the redesign of the entire agrifood system [14], in which the complex relationships established between ecological functioning, human well-being, innovation, governance models and bottom-up policies are integrated. In this way, agroecology imparts a socio-ecological perspective to the context of agroecosystems [15,16]. The offspring of the vertical and specialized model of technology transfer from scientific centers and national programs to agroecosystems that contribute to local food is evident in the dysfunction at the level of action within the food system, the lack of alignment with the socio-cultural, ecologicalenvironmental and economic-financial characteristics of different territories, and in failing to recognize local experiences in adapted traditional practices.

Transition towards decentralized co-innovation

Co-innovation in primary food production is moving from systems with a vertical approach to more horizontal ones (Figure 1). Although this does not happen in the same way in all programs, institutions and projects, there is a tendency to maintain the former when the focus on conventional intensive production aligns with input substitution; whereas the latter emerges from agroecological movements, where these converge with peasant farming systems, projects and organizations that facilitate co-innovation. In the latter, there is a strong influence from projects facilitated by international agencies that have experience in participatory innovation with equity. Conventional technological innovation has an initial stage in which the new technologies developed by research centers are turned into technical standards and published in manuals and technical instructions, considered as ‘national recipes’ (Figure 1A); although in many cases, they later establish vertical innovation systems known as ‘Technology Transfer,’ where groups of extension agents intervene in representative environments to implement the newly developed technologies (Figure 1B). The technology transfer approach, which was widely disseminated in association with the concept of science, emerges from the ‘green revolution’ model. It is a way of ‘doing science’ in a centralized manner in agriculture and assumes that professional researchers know the priorities of farmers and that they adapt the technologies designed in public or private research institutions.

Figure 1:Transition in agricultural technological innovation processes.

Caption: From the vertical model to the horizontal one. From disciplinary to multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary.

The very division of disciplines and specialization of knowledge excludes the possibility that farmers or innovative clients could lead the design, implementation, and dissemination of a new variety, crop, or technology [17]. Research centers, universities and agricultural extension systems have generally regarded farmers as the recipients of their technologies or the users of their services; that is, the goal of their research. However, farmers have much to contribute to the processes of technology generation and transfer, since as the main actors in agricultural production, they have developed a holistic understanding of agriculture and extensive experience with technological processes under their own conditions, which has been little utilized by these centers [18]. A disruptive change occurs when projects in scientific centers adopt decentralized participatory innovation (Figure 1C); however, being a new methodology, there have been various interpretations of what is considered participation: from merely using farmers to test technological proposals, to involving them from the research process itself. This trend towards horizontality in technological innovation generates impressive impacts on the benefiting territories and research teams; the latter begin to adjust in their experimental designs and in new variables for the participatory evaluation of their results. Two examples that represent progress in this regard in Cuba: the local agricultural innovation system of the National Institute of Agricultural Sciences-INCA [19] and the innovation system of the Indio Hatuey Pasture and Forage Experimental Station-EEPFIH [20].

A significant contribution to understanding these aspects has been the rise of Participatory Action Research (PAR), which emerged from the social sciences and was enriched by questioning the extension and training systems used for agricultural modernization. It is based on the idea that any development process undertaken will be biased if it does not consider the realities, needs, aspirations and beliefs of the beneficiaries and even more so if it does not integrate the beneficiaries of this process as protagonists, who explain their reality comprehensively (systemic approach), in order to initiate or consolidate a strategy of change (transition processes), alongside an increase in political power, both aimed at achieving positive transformations for the community at the local level and at higher levels to the extent that it can connect with similar experiences [21]. There are (or we can rely on) theoretical and conceptual frameworks to work in cooperation among (and with) different actors, for the co-design of innovations, such as action research, intervention research, or more generally collaborative research [13]. It is about the emergence of action research, being able to align the desire for change (of farmers and other actors) with the research intent [22]. A disruptive change occurs in territories where cooperative self-management is facilitated (Figure 1D), to carry out transdisciplinary co-innovations with the active participation of farmers and technicians, through networks or local agroecological movements, who advance in co-innovation capacities to solve their technical problems, share experiences and adopt appropriate practices from formal research.

Two facilitation devices that have advanced towards transdisciplinary horizontal co-innovation are: the Agroecological Farmer-to-Farmer Movement [23] and Participatory Plant Breeding [17,19].

The Farmer-to-Farmer (F to F) Methodology, which in Cuba has been structured as a decentralized system, functions as a coordinated movement facilitated by the National Association of Small Farmers (ANAP). It encourages farmers themselves to take a leading role in learning and innovation through the exchange of experiences according to local characteristics. Participatory Plant Breeding also constitutes a powerful example of a decentralized facilitation mechanism for local areas, linking scientific centers that manage germplasm with primary food production systems run by experimental farmers, who play a leading role in achieving high-impact results in the regionalization of varieties, the rescue and conservation of traditional varieties and the adaptation of germplasm to climate change, among other things. The co-creation of knowledge is gaining recognition and use within science, practice and the agroecology movement. It offers a compelling and adaptable approach and outcome to the increasingly complex challenges faced by farmers and the agri-food system [24].

There are different sources of knowledge: scientific knowledge, indigenous knowledge, peasant and traditional knowledge, knowledge from civil society and community organizations, lived experiences and other forms of knowledge that form the basis of the fundamental knowledge of agroecology, regenerative agricultural practices, and indigenous food customs [5]. Knowledge can be tacit or explicit. Tacit knowledge is characterized by being personal and difficult to formalize to be transmitted; it depends on the context and its trajectory, individual capabilities (talent and cognitive abilities), skills (know-how), as well as experience, decisionmaking models of individuals, perceptions, and beliefs [25]. Explicit knowledge is documented in various media, which can be accessed. The “virtuous” dimension of innovation processes is not only about obtaining new products, new ways of managing or organizing, but also about generating learning among the actors. This learning will not only allow the actors to work together, innovate, adapt, or adopt new technology, but it will also be useful in the ordinary (everyday) work of the actors in companies, organizations, and territories to “exploit” or “explore” new situations [13].

Precisely, Agroecological Knowledge Management (AKM) is a contextual, inclusive and multiplier process, carried out in two phases, which can be sequential or simultaneous: the transdisciplinary articulation of local actors and the agroecological transformation of systems. The purpose is to contribute to the coherent integration of people from different disciplines and entities, to achieve complementarity in training, systematization of experiences, co-innovation and communication, so that the process of adopting practices (designs and management) effectively contributes to the transformation of food systems into sustainable ones [26]. In this sense, it is important to understand that Transformative Learning is the process through which we transform our given frames of reference, so that they become more inclusive, open, capable of change and reflective, to generate beliefs and opinions that prove to be true or justified to guide action [27].

When knowledge management and technological innovation converge from vertical agricultural extension systems with local projects or movements that facilitate transdisciplinary coinnovation, a scenario is created that can be conflictive when there are no synergistic integration and coherence in the sustainability approach, slowing down the transformation towards sustainable food due to technological uncertainties among farmers and technicians. On the other hand, scientific centers and national programs that are proactive towards innovation in institutional management, which move towards decentralized action as hybrid devices, become drivers of transformation.

Territorial co-innovation for the transition towards sustainable local food systems

With the recent trend of new public policies aimed at transitioning towards sustainable local food systems, the territory is being reconfigured as a new stage for co-innovation, where it is necessary to understand that the field is not only about agricultural innovations, but also relates to industrial processes, marketing, healthy eating and others that are represented in different sectors and scientific institutions, created under the multisectoral model of doing science. Its local articulation in transforming the food system towards sustainability requires coherence around sustainability attributes, serving as a reference framework for food governance. Of course, for these diverse sources of scientific results to be applicable to territories, viewed as food systems, there needs to be organized and coordinated local mechanisms that act as hybrid actors facilitating the proper integration of new technological and management proposals, because their isolated vertical implementation does not lead to sustainability. This requires that local entities facilitate processes of agroecological transformation to move towards sustainable food systems. They also need to carry out institutional innovations to promote changes in their actions, shifting from separate training and innovation towards a culture of agroecological co-innovation with equity. In this way, they also contribute to making their management sustainable for these entities and the territory [26].

Therefore, entities operating at the territorial level must understand that institutional innovation precedes technological innovation, since the former transforms the ways people interpret and intervene in changing things, while the latter transforms material reality by changing “things” under the influence of the premises of the people leading the innovation process [28]. There is a need to have competent teams in agroecology, who possess multidimensional skills: scientific, practical, political, communicative, financial, market knowledge, and socio-economic transformation [5]. In this effort, it is important to develop systems thinking, understand organizational dynamics and promote the hybridization of knowledge as key elements to advance these ongoing processes [29], described as a “whirlwind” or “virtuous spiral” of innovation [30], which reinforces the role of the territory as a key space for dialogue and experimentation, where common languages are built and niche innovations emerge [31,32].

The most radical importance of co-evolutionary interactions among agents in a complex system is that they allow the development of certain properties that are truly fundamental in fostering diversity, innovation, learning, and sustainability in any complex organization. These characteristics (though there may be more) have summarized as: reciprocity, learning, strategic development, spatiotemporal dynamics, multiscale nature, propagative and expansive qualities, and emergence [33]. In fact, territories are undergoing a constant process of transitions, which includes broader changes related to ecological, political, economic, and other factors that operate at multiple scales. Agroecological transitions are strategic processes of collective action aimed at achieving more ecological and social just food systems [7]. The transition to a more sustainable way of life requires a significant change in the way problems are perceived, defined and solved, based on an open systems perspective, in which both problems and solutions are managed holistically [34].

An innovation systems approach that fits perfectly with the idea of the horizontal creation of knowledge inherent in agroecology is what is known as co-innovation [35], which combines the complex systems approach with social learning and the dynamic monitoring of innovation projects. Co-innovation platforms include diverse actors, from producers to scientific technicians, extension agents, representatives of governments, technology and input suppliers, the market, etc. [36]. The ability of local processes to build hybrid forums, as an area in which innovation niches and the dominant socio-technical regime are intertwined, has been identified as a key element in constructing transitions towards sustainability in local agri-food systems [37,38]. Such hybrid forums have been characterized in relation to stable innovation networks, which connect actors involved in innovation niches (which we will call alternative actors) with actors more aligned with the reproduction of the dominant socio-technical regime (which we will call conventional actors) [38]. This diversification of the subjects of the transition, with an emphasis on hybrid actors who facilitate the establishment of bridges of communication and cooperation between alternative and conventional actors, has been noted in relation to a context of crisis in local development models, but also with the inability of alternative food networks to generate models that are both pure and viable, outside the conventional and globalized agri-food system [37,39].

The social and ecological coevolution developed in agroecosystems is the result of a coevolution, in the sense of integrated evolution, between culture and environment [40,41]. Cognitive contributions need to interact with attitudes, feelings, values, and ideas to have meaning; this allows for the incorporation of new practices in personal and social spheres; thereby demonstrating that the informational approach alone is not sufficient to generate personal and social change [42,27]. In agroecosystems, when we consider both the components of a natural nature and those of a social and cultural nature, we encounter the term coevolution [43]. Each ecosystem has evolved and modified over time through the interactions and influences that its different components have exerted on one another. In this interaction, natural components have been defined and modified, as well as the social and cultural components of the human groups immersed in them [44]. It is a coevolutionary process that defines the current state of ecosystems, as well as the sociocultural identities that coexist with them [45].

Social innovation has various definitions and theoretical approaches. The approach that highlights the potential of innovation strongly linked to the existence of social networks and the social capital available at the local level is very important, as is the idea that the development of social innovation goes far beyond technological advances and focuses on changing the attitudes and behaviors of a group of people organized in a network with similar interests, which leads to new and better forms of collective action than outside of it [46]. To facilitate the agroecological transition, it is necessary for society to take ownership of several elements of the systemic approach of this science: a) agroecology for sustainability, b) the characteristics of the context, c) people’s perceptions, d) the scope of the agroecological transition in the territory, e) the disciplines and trans disciplines involved, f) open access to the various sources of knowledge, and g) participatory methods for transformative action [47].

From this approach, recent studies point to a scientific paradigm shift to address the agri-food system from sectoral theoretical approaches to systemic approaches supported by decision-making processes linked to territorial governance. From a holistic perspective, agroecology considers that the problems of the agricultural system cannot be studied independently of the human communities and social contexts in which they are situated [48]. Because most local entities that provide technical services have generally been created under the conventional food approach, their management system remains vertical and disconnected from the rest of the entities, even though their services serve the same beneficiaries. For this reason, they must transform their system toward participatory management and create local networks as cofacilitation devices, so that their actions are also sustainable.

Valuing local knowledge management

For knowledge management to be sustainable, it must consider the various existing sources of local knowledge and access to appropriate external sources, through local mechanisms that link them to integrate the co-creation of cognitive capacities (technical training) and co-innovation (adoption of technologies) in a way that is consistent with the characteristics of the territory. The great challenge of local knowledge and innovation management is to break down the structural and operational barriers that hinder articulation at the territorial scale, to achieve convergence among the different existing sources of knowledge and facilitate the local flow of tacit and explicit knowledge from various sources, such as the following:

Multilateral: It is expressed in the cooperative actions of entities that belong to national organizations, through commissions or other mechanisms that are often formal because they are managed by one-way methods; therefore, it is sensitive to the fact that transformations may not occur, as it is based on “integrating” explicit knowledge (sometimes established by these organizations), which is enriched with the tacit knowledge of the members of these mechanisms. Proposals or decisions are generated that are not always compatible or appropriate for the context [26]; however, it is considered a source of knowledge updated from the perspective of recent scientific results and documented explicit knowledge.

Local entities: In municipalities, a variety of local entities and civil society organizations work together, each with specific functions of their respective governing centers. In the case of agricultural production, they carry out undergraduate training (polytechnics, universities) and skills training (technicians, workers, farmers, others), which in some municipalities achieve synergies in their management with mutual benefit [26]. This source of tacit knowledge has great contextual value because they know the territory and have mastery of the practices used and their adaptation.

Farmers: There are four dimensions [49]: (a) knowledge about local biological taxonomies; (b) about the ecological environment, which includes the geographical, physical, vegetational, and biological realms [50]; (c) about agricultural practices, and (d) experimental peasant knowledge. This is without diminishing the more general cultural knowledge of the social fabric such as health, food, construction, myths, art, festivals, which helps them to sustain themselves. This knowledge about nature can be classified into three areas: (a) structural, referring to natural elements or their dynamic components, when it concerns processes or phenomena, such as lunar cycles, erosion, ecological succession, life cycles; (b) relational, when it is linked to the relationship or within elements or events; and (c) utilitarian, to indicate knowledge about the use of resources [50]. It is a very important source of knowledge because it is based on the rationality of farmers and on peasant experimentation.

Knowledge management refers to the process of creating, disseminating, and incorporating knowledge into new products, organizations, etc. It involves identifying, grouping, organizing and continuously sharing/mobilizing knowledge of all kinds to meet current needs and explore possible futures, to identify and exploit knowledge resources, both existing and acquired, and to develop new opportunities [10]. Innovation is defined as the introduction of recent knowledge or novel combinations of existing knowledge to transform them into products and processes with economic impact [51], where only scientific knowledge is considered. Agroecology is a complex socio-technical, organizational and contextual/ territorial phenomenon [13], which in particular suggests a broad approach that allows understanding (considering) agricultural action in holistic terms, proposing that contemporary production issues have evolved from a purely technical dimension to a more sociotechnical dimension, where social, economic, political, and ecosystem aspects are present and are part of the situation. In other words, the central concern today is the sustainability of agriculture, conceived as a system that is economic, social, and ecological [12].

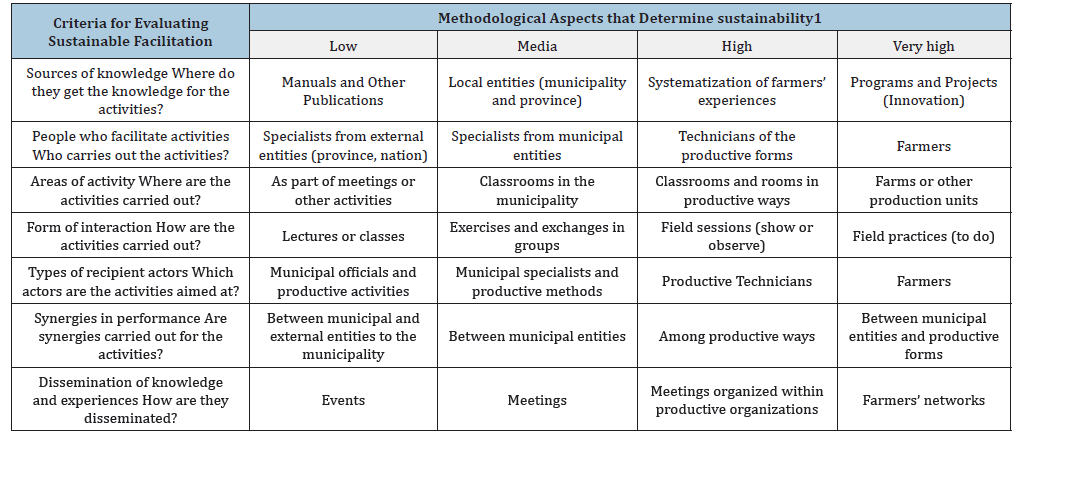

The local management of agroecological knowledge is based on the interaction among actors, which is why it must be inclusive, because in addition to being transdisciplinary, it values the experience of older adults and the perceptions of young people, whether women or men and does not exclude contributions from people with different occupations; precisely because the holistic approach of agroecology requires multiple perspectives that come together in practices appropriate to each context [26], among other criteria and methodological aspects that are decisive for its sustainability (Table 1). For example, regarding the transition in the management of agroecological knowledge in Cuban territories, during the 1980s, training and technology transfer were established as a vertical model in the agricultural sector, managed nationally by various scientific and development institutions, with the collaboration of local entities and specialists.

Table 1:Criteria used to design, facilitate, and assess sustainability in local management of agroecological knowledge (26).

(1) Sustainability is a relative assessment, carried out through a percentage distribution (low, medium, high, very high) based on 100% of the aspects that determine the sustainability of each criterion.

The existence of more than 20 independent research centers in the agricultural sector, far from being an advantage, constitutes an obstacle to the development of integrated innovation processes, since technologies are generated and disseminated by the research centers themselves, and it is up to the farmer to integrate them on the farms, which results in the underutilization of human talents and resources in the research centers, as well as certain losses in expenses and technological incompatibilities [52]. With the rise of Agroecology in Cuba since the mid-1990s, this model gradually adjusted to allow greater participation and recognition of the experiences of local technicians and farmers. For this reason, researchers from these national institutions began to interact with them, fostering what was considered agroecological training, with the Peasant-to-Peasant Agroecological Movement standing out [53]. At the same time, various research centers were moving towards participatory research, such as the Participatory Plant Breeding project [17].

Figure 2:Summary of the transition towards local management of agroecological knowledge in Cuba.

The management of agroecological knowledge in Cuba is moving towards greater sustainability, characterized by: local sources of knowledge, facilitators of activities (specialists from municipal entities), meeting spaces (classrooms and halls in municipal entities), forms of interaction between actors (lectures or classes), receiving actors (farmers), local synergies in action (municipal entities and productive forms), dissemination of knowledge and experiences (events), are predominant [26]. In fact, although training and innovation are planned and carried out as different activities to be implemented through vertical methods, they have been coevolving toward their integration in the territories where projects and programs operate, as transdisciplinary systems for the local management of agroecological knowledge (Figure 2). However, in the face of the challenge of building sustainable food systems, local management of agroecological knowledge requires strengthening several components, such as: fostering institutional innovation (popular education, transformative learning, design thinking, participatory governance, proactive communication); decentralizing and contextualizing technical innovation (on-farm research, farmer experimentation, networks of innovative farmers); transdisciplinary local innovation (co-innovation); disseminating explicit knowledge (meetings, workshops, brochures, videos); turning tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge (systematizing experiences) and exchanging tacit knowledge (participatory exercises in meetings and workshops), among other components such as foresight to move towards sustainable agriculture.

In fact, in these territories, different narratives coexist that contrast conventional production and marketing with sustainable practices. These are expressed in the actions of individuals, entities and organizations involved in the governance of the population’s food supply, most of whom play a significant role in the establishment of public policies, strategies and actions. This situation, which is characteristic of various territories, highlights the existence of theoretical and methodological inconsistencies in the adoption of agroecology. This is evident in meetings, courses, events and other types of collective activities, where diverse interpretations and proposals on the subject can be observed. These differences are not only seen in the realm of production and marketing but also in other sectors such as technical services, research, education, health and communication [47].

The challenges of the agroecological transition are often discussed. Such challenges can be social, biological, economic, cultural, institutional, political, etc., and addressing each of them requires strategies and technological, organizational, and institutional innovations. In other words, the transition toward sustainable food production through the principles of agroecology requires not just one transition, but several simultaneous transitions, at different scales, levels, and dimensions [36]. Several factors can act alone or together to promote and sustain the territorial scaling of agroecology [54-56]: (a) crises that drive the search for alternatives; (b) social organizations; (c) constructivist teaching-learning processes; (d) effective agroecological practices; (e) mobilizing discourse; (f) external alliances; (g) favorable markets; (h) favorable political opportunities. Regardless of these or other determining factors in the transition towards sustainable food systems, progress or slowdown is determined by the creation of local devices for transdisciplinary articulation, composed of people trained in facilitating participatory processes; because existing devices are usually based on conventional food systems, which generally operate under the technology transfer model, whose methods of action are basically top-down and pseudoparticipatory.

Recommendations and Conclusion

Territories that are transitioning towards sustainable food systems should design and create knowledge management systems that bring together actors who determine critical local knowledge and external entities that generate appropriate technologies, through synergies and mechanisms that operate via programs, projects and interest networks. During the early years of the transition to sustainable agriculture, specialized research centers contribute with product technologies (bioproducts, varieties, breeds, energy sources, others) that serve as substitutes for conventional ones; meanwhile, comprehensive centers also provide process technologies (farming and livestock systems, soil management, others). Although these contributions are necessary, the transformation of agroecosystems into sustainable ones is achieved when innovative processes take traditional practices and farmers’ experiences into account, as a robust criterion for adapting technologies to the characteristics of landscapes and agroecosystems.

References

- Bui S, Cardona A, Lamine C, Cerf M (2016) Sustainability transitions: Insights on processes of niche-regime interaction and regime reconfiguration in agri-food systems. Journal of Rural Studies 48: 92-103.

- Meynard JM (2017) L’agroécologie, un nouveau rapport aux savoirs et à l’ OCL 24(3): 303.

- Deverre C and Lamine C (2010) Alternative agri-food systems: A review of English-language works in the social sciences. Économie Rurale, pp. 57-73.

- Lepratte L, Blanc R, Pietroboni R, Hegglin D (2010) Socio-technical production systems and innovation. Analysis of the dynamics of the poultry meat production sector in Argentina. Ibero-American Magazine of Science, Technology and Society 10(28): 57-83.

- Global Alliance for the Future of Food (2021) The politics of knowledge: Understanding the evidence for agroecology, regenerative agricultural practices, and Indigenous foodways, pp: 1-114.

- Lastres HM, Cassiolato JE, Arroio A (2004) Knowledge, innovation systems and development. Rio de Janeiro, Editora da UFRJ y Contraponto.

- Anderson CR, McCune N, Bucini G, Mendez VE, Carasco A, et al. (2022) Working together for agroecological transitions. Perspectives on Agroecological Transitions-No. 3, Agroecology and Livelihoods Collaborative (ALC), University of Vermont, Burlington, USA.

- Chambers R, Ghildyal BP (1985) Agricultural research for resource-poor farmers: The farmer first and last. Agricultural Administration 20(1): 1-30.

- Tripp R (1991) Planned change in farming systems: Progress in on-farm research, In: R Tripp (Ed.), John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, England, pp. 3-16.

- Muñoz M, Rendón R, Aguilar J, García JG, Reyes J (2004) Innovation networks. An approach to their identification, analysis, and management for rural development. Research and technology transfer program, Michoacán, Produce Michoacán Foundation, Chapingo Autonomous University, Mexico.

- Bas E, Guilló M (2011) Foresight and culture of innovation. Ekonomiaz 76: 18-37.

- Altieri MA (2010) The state of the art of agroecology: Reviewing progress and challenges. In: T León, MA Altieri (Eds.), Aspects of Agroecological Thought: Foundations and Applications. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Bogotá, Colombia. pp. 77-104.

- Chia E (2018) Agroecology: A new paradigm for family farming and territorial development. The Contribution of the Virtuous Trifold of Innovation, Learning and Governance, Cangue 40: 10-14.

- Tittonell P (2014) Ecological intensification-sustainable by nature. Current Opinion Environmental Sustainability 8: 53-61.

- García-Llorente M, Pérez-Ramírez I, Sabán de la Portilla C, Haro C, Benito A (2019) Agroecological strategies for reactivating the agrarian sector: The case of Agrolab in Madrid. Sustainability 11(4): 1181.

- Oteros-Rozas E, Ravera F, García-Llorente M (2019) How does agroecology contribute to the transitions towards social-ecological sustainability? Sustainability 11: 4372.

- Ríos-Labrada H (2016) Participatory plant breeding and local innovation. In: Funes F, y Vázquez LL (Eds.), Advances in Agroecology in Cuba. Estación Experimental de Pastos y Forrajes Indio Hatuey, Matanzas, Cuba, pp. 183-198.

- Vázquez LL (2010) Farmers experimenting with agroecology and agricultural transition in Cuba. In: T León y MA Altieri (Ed.), Aspects of Agroecological Thought. Foundations and Applications. Sociedad Científica Latinoamericana de Agroecología (Socla), Medellín, Colombia, pp. 229-248.

- Ortiz R, Acosta R, Ruz R, la O M, Rivas A, et al. (2021) Innovation systems with a participatory approach to local development management. Anales de la Academia de Ciencias de Cuba 11(3): 1-7.

- Miranda T, Machado H, Suarez J, Sánchez T, Lamela L, et al. (2011) Innovation and technology transfer at the Indio Hatuey experimental station. 50 Years Fostering the Development of Cuba's Rural Sector (Part I). Pastos y Forrajes 34(4):

- Guzmán GI, Alonso AM (2007) Participatory research in agroecology: A tool for sustainable development. Ecosystems (1):

- Liu M (1997) Fondements et pratiques de la Recherche-Action. L’Harmattan, Paris, France, p. 250.

- Machín B, Roque A, Rocío D, Rosset P (2010) Agroecological revolution: ANAP's farmer-to-farmer movement in Cuba, La Habana, Cuba.

- Utter A, White A, Mendez E, Morris K (2021) Co-creation of knowledge in agroecology. Elem Sci Anth 9(1): 26.

- Nonaka I, Takeuchi H (2015) Creative Knowledge: The Dynamics of the Learning Organization. De Boeck University Press, Belgium, p. 303.

- Vázquez LL, Chia E (2023) Sustainability of agroecological knowledge management in Cuban territories. Études caribéennes 54:

- Mezirow J (2000) Learning to think like an adult. Core concepts of transformation theory. In: Meziro Jack (Ed.), Learning as Transformation. Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp. 3-33.

- De Souza J, Cheaz J, Santamaría J, Mato M., Lima S, et al. (2005) The innovation of institutional innovation: From the universal, mechanical and neutral to the contextual, interactive and ethical, Quito, Artes Gráficas Silva, Ecuador, p. 370.

- Vitry C, Chia E (2016) Contextualisation d’un instrument et apprentissages pour l’action collective. Revue management et avenir (83): 141-21.

- Chia E, Torre A (2020) Territorial governance through the prism of instruments, lessons learned, and conflicts. Investigaciones Geográficas 60: 18-34.

- Geels FW, Schot J (2007) Typology of sociotechnical transition pathways. Research Policy 36(3): 399-417.

- González-Fernández L, Carámbula M, Rossi V, Viera I, Chia E (2023) A look from the sociology of translation at a territorial innovation in Canelones, Uruguay. Mundos Plurales-Revista Latinoamericana De Políticas y Acción Pública 10(2): 111-132.

- Calvente AM (2007) Coevolution: A central process for sustainability. Universidad Abierta Interanmericana, UAIS, p. 6.

- Gutiérrez JM (2008) How we know a good teacher? Revista Mexicana de investigación Educativa 13(39): 1299-1303.

- Dogliotti S, García MC, Peluffo S, Dieste J, Pedemonte A, et al. (2014) Co-innovation of family farm systems: A systems approach to sustainable agricultiure. Agric Syst 126: 76-86.

- Tittonell P (2019) Agroecological transitions: Multiple scales, levels and challenges. Rev FCA UNCUYO 51(1): 231-246.

- Ilbery B, Maye D (2005) Making reconnections in agro-food geography: Alternative systems of food provision. Progress in Human Geography 29(1): 331-344.

- Elzen B, Barbier M, Cerf M, Grin J (2012) Farming systems research into the 21st century: The New Dynamic, pp. 431-455.

- Darnhofer I (2014) Resilience and why it matters for farm management. European Review of Agriculture Economics 41(3): 461-484.

- Norgaad RB (1987) The epistemological basis of agroecology: En Agroecology. The Scientific Basis of Alternative Agriculture, Boulder-IT Publications, West-View Press, London, England.

- Norgaad RB, Sikor T (1999) Methodology and practice of agroecology. In: Altieri MA (Ed.), Agroecology: Scientific Basis for Sustainable Agriculture, Nordan-Comunidad, p. 31-46.

- Kegan R (2000) What "form" transforms? A constructive developmental approach to transformative learning. In: J Mezirow (Ed.), 1st (edn), Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, USA, pp. 3-34.

- Norgaad RB (1994) Development Betrayed: The end of progress and a coevolutionary revisioning of the future. Reutledge, New York, USA.

- Kallis G, Norgaard RB (2010) Coevolutionary ecological economics. Ecological Economics 69(4): 690-699.

- Pugliese P (2001) Organic farming and sustainable rural development: A multifaced and promising convergence. Sociologia Ruralis 41(1): 112-130.

- Neumeier S (2012) Why do social innovations in rural development matter and should they be considered more seriously in rural developing research? Proposal for a stronger focus on social innovations in rural development research. Sociologia Ruralis 52(1): 48-69.

- Vázquez LL (2024) Social appropriation of agroecology: Key to the sustainable transformation of local food systems. Foro 8(4): 29-39.

- Wibbelmann M, Schmutz U, Wright J, Udall D, Rayns F, et al. (2013) Mainstreaming agroecology: Implications for global food and farming systems. Centre for Agroecology and Food Security.

- Altieri MA (1999) Scientific foundations for sustainable agriculture. Nordan Comunidad, Montevideo, Uruguay, p. 338.

- Toledo VM (1992) The rationality of peasant production. In: Sevilla G, M González de Molina (Eds.), Ecología, Campesinado e Historia, Ediciones La Piqueta, Madrid, España, pp. 197-218.

- Edquist C, Björn J (1997) Institutions and organizations in systems of innovation. In: Edquist C (Ed.), Systems of Innovation: Technologies, Institutions and Organizations. Series Editor: John de la Mothe and Pinter, Ottawa, Canada.

- Caballero R, Vázquez LL (2016) Agroecological innovation. In: Funes F, y Vázquez LL (Eds.), Avances de la Agroecología En Cuba. Estación Experimental de Pastos y Forrajes Indio Hatuey, Matanzas, pp. 471-482.

- Funes F, Freyre E, Blanco F (2016) Agroecological training. In: Funes F, y Vázquez LL (Eds.) Avances de la Agroecología en Cuba. Estación Experimental de Pastos y Forrajes Indio Hatuey, Matanzas, pp. 449-468.

- Rosset PM (2015) Social organization and process in bringing agroecology to scale. In Agroecology for food security and nutrition. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, Rome, Italy.

- Khadse APM, Rosset PM, Ferguson BG (2017) Taking agroecology to scale: The zero budget natural farming peasant movement in Karnataka, India. The Journal of Peasant Studies 45: 1-28.

- Rosset PM, Altieri MA (2017) Agroecology: Science and politics. Fernwood Publishing, Manitoba, Canada.

© 2025 Luis L Vázquez. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)