- Submissions

Full Text

Modern Concepts & Developments in Agronomy

Significance of Moisture in Poplar Production and Wood Handling

RC Dhiman*

Greenlam Industries Ltd., India

*Corresponding author:RC Dhiman, Greenlam Industries Ltd., New Delhi, India

Submission: September 13, 2024;Published: November 18, 2024

ISSN 2637-7659Volume14 Issue 5

Abstract

Paper presents data on Moisture Content (MC) in poplar (Populus deltoides) leaf samples collected from emerging bud sprouts, fully grown and those undergoing senescence. The available published and unpublished data sets on MC have been reviewed in reference to water management to maintain adequate moisture levels in poplar production and its wood during trade and peeling. Moisture content was studied in bud sprouts from three poplar species viz., P. deltoides, P. cilata and P. alba; bud sprouts from saplings soaked in water pit, field planted saplings, and polythene bag planted saplings; leaves from 4 different aged trees; green leaves from the top position of nursery saplings, yellow leaves from the middle position of nursery saplings, and overnight dropped yellow leaves from nursery saplings. P. deltoides recorded a significantly higher MC of 327.44% on a dry weight basis (MCDW) compared to that of P. alba (286.46%) and statistically at par with that of P. ciliata (317.90%). Bud sprouts from water-soaked saplings recorded significantly higher MCDW (363.41%) compared to 315.03% in field planted and 304.01% in polythene bags planted saplings. MC decreased in leaves with increase in age of trees from 7 months to 31 months. Green leaf samples from top position of saplings collected during senescence had significantly higher 159.54% MCDW compared to overnight shed yellow leaves (69.34%). The study also included some wood samples of different aged poplars which along with other data sets were used to develop regression equations to predict MCDW from MC on a fresh weight basis (MCFW) in composite samples that include leaves, bud sprouts, and wood samples together. Separate regression equations were also developed to predict MCDW in each of leaves, bud sprouts, and wood samples separately. MCDW varied widely from over 350% in fresh bud sprouts to less than 70% in overnight dropped leaves. Conversion factor between MCDW and MCFW for samples >300% MCDW was >4, for 250-300% as 3-4, for 150-200% as 2-2.5, for 100- 150% as 1-2, and for <100% as <1. The review on water management and standard operating practices on irrigation in-vogue suggests providing balanced supplies to avoid moisture deficit and excess for producing good quality poplar whereas wood needs to be maintained in saturated conditions just before peeling for good quality veneer production.

Keywords:

Moisture content; Leaves; Bud sprouts; Wood trade and peeling; Water managementIntroduction

Poplar (Populus deltoides) is commercially grown tree for production of peeling logs, the demand of which is fast increasing forever expanding wood-based industry. Its initial commercial plantations were undertaken near the foothills of the Himalayas 4 decades back which gradually expanded both in acreage and geographical locations. The tree is now well integrated with agricultural crop production in agroforestry and is extensively and intensively grown in one of the most productive farmlands of North India. Agronomical inputs applied to agriculture crops are also shared by the tree as a result its productivity in plantations is very high [1]. Besides fertilizers, water is critical input required for production of quality nurseries and field plantations. Tree growers pay adequate attention to water management in its nurseries and plantations for harnessing their biological potential in achieving high productivity.

Water is vital for survival, growth and productivity of plants. Plant living cells need to be more or less saturated with water to function normally [2]. Water, when available at optimum levels, helps in sap flow, translocation of nutrients and photosynthetic elements from one part to others and controls a very large number of plant physiological functions, mechanical properties and physical structure. The water deficit on the other hand has a serious impact on plant growth, health and survival. A study on plant water content in 24 wild plant species was found closely associated with their growth and productivity [3]. For cultivated plants, water in addition to that from natural sources is supplemented through irrigation systems which move near to plant root system through seepage. Water from soil is absorbed by moisture sensitive root system which thereafter is trans-located to stem, branches and leaves through a low resistance pathway of plant vascular system.

Leaf is an extremely important organ of plants and is virtually the food factory for sustaining their life cycle. Leaves are easy to assess, handle and abundantly available for different purposes that may include research in large sized trees. Leaf water content also reflects the water status of other organs & whole trees, and is inherently related to other leaf traits viz., leaf water mass, leaf area, leaf dry matter content, leaf photosynthesis, and leaf carbon assimilation [4]. It also regulates plant food synthesis, maintains water balance through evapo-transpiration in the soil-plantenvironment interface [5]; and could be used to predict wildfire behavior [6,7], and water stress & drought assessment [8]. It also affects nutrient flow, gaseous exchange (carbon dioxide and oxygen) [9], and growth & productivity in plants [10]. Keeping in view the significance of MC in popular, studies were planned through a series of 4 small experiments which include inter-species variation in MC of bud sprouts of 3 poplar species; leaves from 4 different aged trees; bud sprouts from saplings maintained under different moisture conditions; and leaves from different developmental stages during senescence stage to understand the dynamics of MC in the tree. It also reviews existing information on water management for effective poplar production and wood processing.

Material and Methods

Poplars, except a few developed cultivars being almost evergreen, are deciduous trees which undergo complete leaf fall during winter months of January and February. The bud break starts in March and is completed in a short period of around 2 weeks. Its nursery is established by using mini cuttings collected from juvenile shoots of last year grown saplings and are planted first in small cavities during January and February. These cuttings sprout in March and are ready for establishing open nurseries during April and May. A parallel system of nursery production using juvenile stem cuttings of standard 20-25cm length and 1.5-2cm thickness is also used in many nurseries in which stem cuttings are directly planted in open nursery beds during January-February which grow to suitable sapling size for planting during next winters.

Moisture content in fresh bud sprouts and fully grown leaves was studied in a series of 4 small experiments to understand its dynamics in poplar foliage. Samples of bud sprouts used in the study were emerging leaves from buds which were less than half the size of normal leaves. The detail of each experiment is given below:

Experiment No. 1: Moisture content in bud sprouts of 3 poplar species.

This experiment used fresh bud sprouts of 3 different species viz., P. deltoides, P. ciliata and P. alba maintained as grafted shoots. Bud sprouts were collected during the month of March from 2 years old grafted shoots developed on the root stock of P. deltoides evergreen clone (65/27). Five samples were collected at random from each plant type and they were treated independent replications for statistical analysis and to compare the mean values of MC (%) among three species.

Experiment No. 2: Effect of age on leaf & wood MC and other traits.

Leaves of poplar trees/saplings (WSL 39 clone) were collected from nursery and plantations aged up to 31 months during first week of September and were studied for MC. Four different aged poplars were: A-7 months old saplings, B- 7 months old field planted, C-19 months old field planted, and D- 31 months old field planted. Three randomly selected trees/saplings were selected from each age group for which growth traits were recorded. Crown height of trees was divided in 3 equal parts, 5% of the branches emerging from the main stem in each divided part were selected for estimating total number of 1st order branches in each group. Total numbers of fully developed leaves from the top 5th-10th position on 5% of the selected branches in each group were recorded. The leave area of sampled leaves was plotted on graph paper, and surface area per leaf & per tree/sapling was accordingly estimated. For the study of MC in wood, 5 cm wide wood discs were taken from the middle height of trees/saplings of 4 different aged poplars. Seven months old saplings used in this study were first grown from mini cuttings in containers and thereafter planted in open nurseries during May as such the physical age of field planted poplar including nursery age were: 14 (7+7) months for B, 26 (19+7) months for C, and 38 (31+7) months for D planted poplar.

Experiment No. 3: Moisture content in bud sprouts of poplar maintained under 3 conditions.

Fresh bud sprouts were collected from WSL 39 clone soon after bud break during March. The main treatments were: fresh bud sprouts from A-partially soaked saplings in water, B- saplings field planted, and C-saplings planted in 30cm long polythene bags (C). Field planted saplings (B) were provided 2 flood irrigations during the month of field planting (B), and polythene bag planted saplings were given irrigation daily with rose cane.

Experiment No. 4: Moisture content in leaves collected during senescence phase.

This experiment was conducted to know the status of leaf MC (clone WSL 39) while preparing and undergoing senescence during leaf fall stage. Fully grown leaves were collected from 7 months old nursery saplings during the active leaf fall stage in December. The main treatments were A- fully grown leaves from the top 1/3rd portion of saplings, B-yellow leaves from middle portion of saplings, and C-overnight shed yellow leaves from the ground. There were 10 samples for each treatment, and these were also considered as separate replicates for making one way analysis of variance to compare the mean values of MC in each treatment.

Samples of leaves, bud sprouts and wood discs were collected as per details given in each experiment, immediately weighed on collection to record fre sh weight, and thereafter placed in oven for drying till there was no loss in their weight. The dried samples were weighed and accordingly MC was estimated. Moisture content in the manuscript is referred to on dry weight basis (MCDW) though it was also estimated on fresh weight basis (MCFW) for developing regression equations and conversion factors (CF) between the two.

The MC of the samples was estimated using the following formulae:

MCDW (%) =((MCFW-MCDW)/(MCDW)) *100

MCFW (%) =(MCFW-MCDW)/(MCDW)) *100

Where, MCFW = Moisture content on fresh weight basis, and

MCDW = Moisture content on dry weight basis.

The data on MC and other traits studied were statistically analyzed using MINITAB software and inferences drawn for comparing the mean values of treatments under each experiment. An effort was also made to develop the regression equations to estimate MCDW from MCFW for different tree components and composite samples containing leaves and wood from different aged poplars. Data sets of MC of 98 wood samples from earlier study [11] were also used with the data sets of present study to develop regression equations and CF.

The review includes present studied data sets and published information related to popular and similar other plant and tree species. It also includes some unpublished data sets and information for drawing inferences. The emphasis is given on water management in handling its stem cuttings as reproductive material, sapling production in nurseries & trees in plantations, and wood trade & wood processing. Some data sets of large quantity of fresh poplar wood procured by a safety match mill are also interpreted for connecting the significance of MC to wood trade.

Result and Discussion

Experiment No. 1: Moisture content in bud sprouts of 3 poplar species

The data on MCDW of 3 poplar species (Table 1) indicate significantly higher mean value of 327.44% in P. deltoides P. ciliata and minimum of 286.46% in case of P. alba. Men values of MCDW in P. alba was significantly lower compared to the remaining 2 species which had non-significant marginal differences between each other. The range between maximum and minimum values in MCDW was higher by 7.57% in P. deltoides compared to a minimum of 2.68% in P. alba and intermediate of 7.5% in P. ciliata. Both P. deltoides and P. ciliata are adapted to moist locations having adequate moisture availability. P. alba also occurs in cold arid region of Himachal Pradesh and Ladakh region of the Indian Himalayas where this species has a little higher root suckering. Low MC in P. alba among the 3 species studied may be an indication of its higher adaptability to semi-arid conditions compared to 2 other species. The results are in line with the findings of variation in leaf water content in fruit tree species [12] and in leaf metabolic traits in different genotypes of Eucalyptus camaldulensis [13].

Table 1:Moisture content (MCDW%) of bud sprouts in 3 Populus species.

Experiment No. 2: Effect of age on leaf & wood MC and other traits.

All the parameters studied given in Table 2 indicate significant differences among 4 age groups. Mean values of MCDW, in both leave (204%) and wood (122%), were maximum in nursery grown saplings which gradually decreased with increase in age. Leaf & wood MC in 7 months old nursery saplings and 7 months old field planted poplar had non-significant differences between each other at both 0.05 and 0.01 level of significance whereas these values were significantly higher from 19 months old and 31 months old poplar. Leaf & wood MC were statistically at par between 19 months and 31 months old, planted poplar. Some other leaf traits viz., individual leaf area, fresh weight/leaf and dry weight/leaf also decreased with increasing age. Surface area/leaf recorded significantly high values of 252cm2, fresh leaf weight of 6.35g/leaf and dry weight of 2.1g/leaf in nursery saplings compared to those in field planted poplar of all ages at 0.05 of significance. Average values of 2.45g fresh weight/leaf and 1.03g dry weight/leaf were statistically lower than those in 7 months nursery saplings at both 0.05 and 0.01 level of significance. Individual leaf area was statistically at par between 7 months (174cm2) and 19 months (154cm2) field planted poplar at both 0.05 and 0.01 level of significance. Individual leaf area was minimum (88cm2) in 31 months old poplar and it was significantly lower than that in all other aged poplars at 0.05 level of significance. Mean values of leaf No./tree were statistically at par between 7 months old nursery and 7 months old field planted poplar at 0.01 level of significance. Small sized Leaves in older poplar are associated with their lower fresh and dry weight with corresponding increase in age.

Table 2:Effect of age on leaf & wood MCDW% and some other traits.

All others studied traits viz., tree height, DBH, crown diameter, branch No./tree, leaf No./tree, leaf fresh weight/tree, and leaf dry weight/tree recorded significantly higher values in 31 months old poplar compared to nursery grown saplings at both 0.05 and 0.01 level of significance. All these traits recorded gradual increase with an increase in age from 7 months nursery saplings to 7 months, 19 months, and 31 months field planted poplar. With age, the tree along with its organs grew in size/number. Mean values for tree height, DBH, crown diameter, branch No./tree, leaf No./tree, leaf fresh weight/tree and leaf dry weight/tree were significantly higher in 31 months old compared to other 3 aged poplars. Thirtyone months old poplar had 50.1kg fresh leaf weight/tree and 20.9kg oven dry weight/tree which were significantly higher from both of 7 months nursery and 7 months field planted poplar at 0.01 level of significance but significantly at par with 19 months old field planted poplar at 0.05 level of significance. Similarly, tree height, DBH, crown diameter, No. of branches/tree and No. of leaves/ tree had significantly higher mean values compared to 7 months nursery and 7 months planted poplar. Moisture content and some other tree traits in P. deltoides were reported to change with tree height [14]. Some other studies also reported change with age in leaf and other tree traits [15-17].

Experiment No. 3: Moisture content in bud sprouts of poplar maintained in 3 different conditions.

The data given in Table 3 indicate that the average values for MCDW in fresh bud sprouts emerged during March were maximum of 363.41% in those saplings which were kept soaked in water (A) followed by 315.03% in field planted poplar which were provided flood irrigations during field planting (B) and 304.01% in those kept in restricted volume of 10cm wide and 30cm long polythene bags irrigated with rose cane (C). The mean values of MCDW in water pit stored saplings (A) were significantly higher compared to B and C samples. Water-soaked saplings were constantly in contact with water as such they could maintain high MC. Similarly, field planted saplings could maintain adequate MC by absorbing it from applied surface irrigations. Polythene bag planted saplings were planted in long polythene tubes which had limited soil media and water availability and thus could have some degree of water stress that was exhibited in the form of low MC in their bud sprouts. Higher MC in P. deltoides was reported in irrigated plots compared to non-irrigated plots [14]. Fast grown trees were characterized by high moisture content [18] and poplar falls in this category. This is more so in case of bud sprouts which had high water demand for expanding leaves. MCDW in buds was reported progressively increasing until buds opened and this increase was correlated with rapid translocation of moisture from tree wood into the buds [7]. High MCDW of over 300% is also well reported in foliage of broadleaved and conifer species [7] and mulberry [19,20].

Table 3:Variation in leaf MCDW in bud sprouts from different sources.

Experiment No. 4: Moisture content in leaves collected during senescence phase.

Table 4:Variation in leaf MCDW% during different stages of leaf senescence.

The results of this experiment (Table 4) indicate top green leaves have significantly higher 159.54% MCDW compared to overnight shed yellow leaves (69.34%). The difference in MC between the top green leaves on sapling and lower yellow leaves had nonsignificant differences with yellow leaves registering lower MC. Bud set in saplings starts around the middle of November after which poplar height growth ceases. This stage also sets in the process of leaf senescence which progresses gradually by yellowing of leaves and subsequent shedding. Senescence is a highly regulated process in trees and this phonological change is correlated with leaf moisture content, age, season, environment and light. Moisture loss is also reported responsible for heavy damage to leaves due to their drying before senescence [21]. It has been reported that under stress conditions lower leaves are more prone to reduction in their water content [22,23].

The current study indicates seasonal variation in poplar leaf MC. Such seasonal variation is well reported in leaf MC in fruit trees [12], mulberry tree [19], Mediterranean woody trees [24], conifer and broadleaved trees [7], and Sitka spruce [25]. These studies had reported a very high MC (around 300% in most cases) in the new flush that decreased in older leaves. In mulberries this declining trend was reported from tender to mature leaves in all seasons [19] while in another study rapid decline was reported in the early part of growing season after flushing [26]. Though the present study did not have enough data sets to capture complete season-wise or month-wise profile of leaf MC, broadly it could be inferred that MC was extremely high above 350% in emerging leaves in spring which was significantly reduced to less than 70% during leaf fall. September drawn leaf samples had MC values in-between.

Regression Equations

Best fit regression equations were developed for predicting MCDW from MCFW for three different components and are given in Table 5. The samples used for developing these equations include leaves, wood of different ages and clones. MCDW in samples varied from around 61% to over 370%. The range of values in all the five models presented here had wide variation in MCDW viz., 61-185% for leaves, 255-370% for bud sprouts, 61-185% for composite leaves and wood, 76-175% for wood, and 61-185% for Conversion Factor (CF). Regression equations were also developed for a conversion factor (CF) between MCDW/MCFW from MCDW. These models were selected based on the maximum value of coefficient of determination (R2). The sample size, range of MCDW, and R2 indicate that their reliability may be effective to the range of samples mentioned in each case as such the developed regression equations could effectively be applied for MC range given for each model. In earlier study the regression equations were developed to predict the weight loss and economical loss in drying poplar logs [27].

Table 5:Regression equations for predicting MCDW from MCFW for different tree components.

Coefficients of correlation between MCDW and MCFW for leaves were 0.98(p<0.000), 0.995 (P<0.000) for bud sprouts, and 0.987 (P<0.000) for wood. Extremely high MCDW, had high CF of >4 in bud sprouts and low of <1 for overnight dropped leaves. A general trend in CF for samples having different MCDW in studied samples is given in Table 6. Conversion factor for poplar logs was developed for samples with varying from 83.15% to 128.34% MCDW. Conversion factor of 1.83-2.91 was reported between MCDW/MCFW in Diptercarpus indicus [28] and P. deltoides logs [11].

Table 6:Conversion factors between MCDW and MCFW for broad categories of MCDW.

Moisture Managementi Nurseries and Plantations

Poplar is adapted to riverian landscape in its natural habitat [29] which inherently has adequate moisture for its growth and development. Poplar maintains adequate water balance within its different organs in consonance with soil and other environmental conditions existing in its ecosystem. Many of its tree traits like fast growth, light and colorless wood, straight stem, low taper, and straight grain makes the tree favorable in plantation forestry. As a result, poplar has been introduced in many region and countries [30] those may or may not have exacting growing conditions to its native habitat. Irrigation is one of the important inputs in its plantations in most regions and countries. In India, the tree is largely grown on farmland with assured irrigation that is applied to agriculture crops and /or trees depending upon their respective water requirement [1]. This section addresses the significance of moisture/water management in handling poplar stem cuttings such as reproductive material, sapling production in nurseries, trees production in plantations and wood handling during its trade and processing for product manufacturing. It is reviewed based on the existing published information and personal experience.

Poplar could be vegetative propagated using stem, root & leaf cuttings, layering, and grafting [31]. The most common method of propagation is the use of mini stem cuttings of 8-10 cm length and standard stem cuttings of 20-25cm length. The former are first grown in cavities and thereafter planted in open nurseries while the later are directly planted in open bed nurseries. Cuttings on collection need careful handling to maintain adequate MC for good rooting, sprouting and growth after planting. At times, there is unavoidable delay in their planting after collection from mother material due to inadequate logistic arrangements and also due to transportation over long distances from collection site to nursery site. Any delay in planting the cuttings after collection results in MC loss which may lead to their dehydration with increased exposure. In plants, the early stage of plant dehydration starts with decline in the relative water content from full turgor to approximately 55% during which leaf color changes from green to yellow [32]. Further dehydration leads to shutdown of photosynthetic mechanisms with gradual loosing vigor which is often exhibited with the reduced ability to sprout, root, compete with other organisms, and survive [33].

The dehydration behavior was studied in poplar cuttings made from 10 days dehydrated mother saplings by keeping them in open conditions on lifting from nurseries [34]. It was observed that cuttings started losing significant moisture after the 2nd day of exposure which reached 18.7% by 6th day exposure. Sprouting, rooting, and survival of cuttings decreased with increase in exposure. It was also observed that thin cuttings lost more moisture and much faster than that in thick cuttings. Thin cuttings made from the upper 1.3rd portion of saplings had higher initial MC compared to thick cuttings prepared from bottom 1/3rd portion of saplings. The simple coefficient of correlation (r) between MC of cuttings and their survival was -0.729 (P<0.001) indicating decrease in MC results in corresponding decreased survival in saplings and cuttings.

The dehydration effect of the above-mentioned 10 days exposed saplings was also studied on their field performance. After exposing saplings for 0-10 days, they were soaked in water for 24 hours before field planting [34]. Exposed saplings up to 3+1 days (3 days of exposure+1 day of water soaking) resulted in 100% sprouting which gradually reduced to 75% in saplings having 5 days (4+1) exposure and 50% thereafter till 11 days (10+1). Other sprouting parameters viz., No. of sprouts, length of leading sprout, No. of leaves/sprout, length and width of leaf blade also had similar trends of decrease with additional exposure up to 11 days.

The recovery of vigor after dehydration was studied in 7 days exposed saplings by soaking them in water from 0 to 240 hours 10 treatments (at 24 hours interval) including 2 control treatments viz., 1- planting saplings immediately after uprooting, and 2-soaking freshly uprooted saplings for 24 hours before field planting [34]. Results indicate sprouting between 12 to 37% in all the recovery treatments compared to 100% sprouting in 2 control treatments. Others studied parameters viz., No. of sprouts, length of leading sprout, No. of leaves/sprout; length, and width of leaf blade recorded decreasing values with increase in exposure in recovery treatments whereas both the control treatments had maximum values for these traits. The sprouting in dehydrated saplings was considerably delayed compared to control saplings. It was inferred from these results that poplar saplings once getting dehydrated could not restore their original vigor as exhibited in adverse values of all the studied traits in exposed mother saplings. Plants with high vigor grow and establish quickly compared to those with low vigor [33].

There have been some attempts to preserve the MC of cuttings by using different methods. In an effort, cuttings were dipped in slurries made by using cow-dung, clay & combination of both, and stored up to 28 days under shade in February before planting [35]. Clay slurry dipped cuttings gave significantly higher survival above 90 % till the 10th day of storage before planting compared to untreated cuttings which started dehydrating much earlier and there was no sprouting in such cuttings after 3 weeks. Days taken for sprouting were less in clay slurry dipped cuttings followed by that in cow-dung+ clay slurry and maximum in shade stored cuttings without slurry dips. Slurries formed a thin layer of covering on cuttings that sealed their surface to reduce moisture loss and delayed their dehydration.

Water Management in Nurseries and Plantations

Effective moisture management is critical for poplar at every stage of its nursery and plantation production. Standard operating procedures have been developed to address irrigation schedules during the critical stages in poplar production phase which include applying irrigation to agriculture crops which is also shared by the trees while growing together [1]. Currently, the standard operating activity employed is to keep the cuttings submerged in fresh water till they are planted in the nurseries (Figure 1A). There are numerous nurseries growing a few million poplar saplings where this activity of cutting making and planting continues for 2-3 weeks. Cuttings made from last year’s grown saplings are divided into 3 groups depending upon their thickness and each group is kept in different water pound or container filled with water. Thin cuttings lose moisture more quickly compared to thicker ones and therefore they are separately planted. Nursery beds and planted containers provide good irrigation just after planting to maintain adequate moisture required for early rooting and sprouting of cuttings.

Figure 1:Improving and maintaining MC by soaking stem cuttings in water before nursery planting (A), soaking basal portion of saplings in water before field planting (B), and constant spraying water on matchwood logs during storage for peeling (C).

The same standard operating practice is followed by saplings lifted from nurseries (Figure 1B). Most poplar nurseries make water pits/channels for soaking basal portions of uprooted saplings before being handed over to the farmers. In case soaking is not done in nurseries, farmers themselves soak saplings in water pounds/channels for 24 to 48 hours at the plantation sites before planting. At times, planting of saplings procured from nurseries get delayed due to numerous unavoidable factors and in such cases, these are kept soaked in fresh water for 3-4 weeks without much adverse effect on their survival and growth.

Surface irrigation is the common method applied for irrigating its nurseries. Nurseries need two irrigations during the week of planting and one/week thereafter till plants start producing new shoots. Additional irrigation may be required during hot summers when soil dries much faster and demand for water intake by plants increases significantly. The demand for irrigation in nurseries raised on ridges using mini cuttings is 20% less than traditional nurseries as the former are planted late in April and May and also water does not reach the upper parts of ridges during flooding the channels. Once the growing plants make leaf canopy over land, soil drying is less, and accordingly overall water demand reduces with reduction in evaporation of soil moisture under shade. The demand for irrigation significantly reduces during July August and September months due to rains. Nurseries are given extra 1-2 irrigations during senescence stage to maintain good turgidity in saplings before their lifting and field planting. 12-15 irrigations are suggested per acre during the nursery production phase which involve around Rs. 5500/acre (8% of total production cost except material cost) expenses. Water management in nurseries also includes draining stagnated water during rains to avoid lodging of saplings and also to avoid infection of insect pests and diseases.

Poplar (P. deltoides) is commercially grown tree in Indogangetic plains where none of the native or exotic Populus spp was ever grown/ existed in the past. These locations are characterized by high temperature and low humidity during dry summer months viz., May and June. On such exotic environments the success of its plantations is largely dependent on availability of good quality water for irrigation which is considered crucial for poplar plantations in many water-limited regions [36]. As a result, almost all its plantations are grown with assured irrigation facilities. In non-irrigated plantations the tree develops water stress in the form of yellowing and wilting of leaves with additional susceptibility to heart rot and termites during hot summers. The productivity of such plantations and quality of wood is very low, and as such, farmers do not find their growing economical on non-irrigated fields.

Like nurseries, plantations are also supplied with water through surface irrigation though other methods like sprinklers and drip irrigations have also been tried in isolated cases which could not become popular due to higher costs and multiple cropping under poplar-based agroforestry. The complete schedule of irrigating poplar plantations is summarized in its standard operating activities [1]. Surface irrigation provides water near to ground surface which is readily accessed by its spreading root system. Its saplings hardly carry original roots while being planted and good surface irrigation during the first month of planting helps the planted saplings to generate multiple roots from their stem below the ground surface to access moisture from the upper layers of soil. Once the saplings are established, they are largely irrigated along with agriculture crops. Water demand is little higher in the first-year plantations, especially just after planting. A couple of irrigations may be applied during the hot summers when there may be no seasonal intercrops in its fields. Based on long experience of growing poplars, an average of 5 irrigations are provided to its fresh year plantations, 4 to 2nd and 3rd year, 3 to 4th and 5th year and 2 thereafter. The current cost of irrigation is around Rs. 500 to 600/acre which is paid labor for channelizing the surface water along three rows.

Heavy rains during monsoon season seldom create swampy conditions in low lying areas where some percentage of trees get bending and some are blown away with winds. Stagnated rainwater in its plantations for long periods also invites number of pathogens besides checking growth that sometimes may lead to increased mortality. Improvement of drainage in such low-lying areas by pumping or channelizing water to natural drains is routinely attempted. There is also a great deal of effort to strengthen bended trees during this period.

Moisture Management in Wood Trade and Processing

Wood is the main product of poplar for which it is commercially grown in the country. Poplar wood harvest and trade spread throughout the year. Normally poplar is harvested and converted to tradable selling grade sizes during the day, transported to marketing centers and mill gates during the following night, sold next morning, and peeled during the next few days. Most peeling mills use fresh wood logs with adequate moisture for defect-free peeling. Small sized mills in India procure peeling logs on short term basis to avoid blocking their money in making wood inventory. Peeling mills in many countries are well integrated where large log inventories are maintained and handled by preserving the procured logs in water till, they are processed. Log peeling by large sized mills generally get delayed as the volume of wood handled by them is considerable large. Many peeling mills also make some wood inventory to ensure continuity of peeling operations. There are many other issues related to transportation, logistics, labor and operations which enforce making some wood inventory which delay the processing poplar wood for peeling. Such mills use water spraying on stored logs till they are peeled (Figure 1C). Growers prefer to sell their wood quickly on harvesting to avoid loss in wood moisture and weight which increases with corresponding increase in wood storage period.

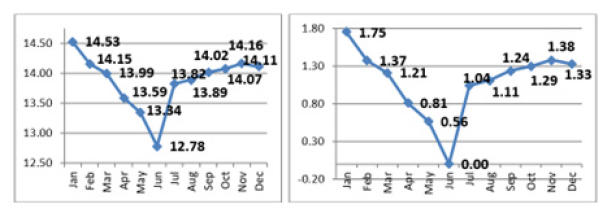

Wood MC varies in different seasons, and it has significant impact on wood trade. It is illustrated with a case study of monthwise matchwood procured throughout year in a Wimco safety match mill. A complete spectrum of poplar matchwood (>45cm mid-girth logs) procured month-wise throughout the year had wide variation in CF between its weight and volume. There was a procurement of 4603.74cmh (cubic meter hoppus) matchwood logs weighing 63875.66qtl (quintal which is one tenth of a ton) during different months of the year. All this wood was procured fresh from agroforestry plantations. The average gap between tree harvest & log documentation including measurement and weighing was generally 2-3 days. Month-wise log data had maximum weight of 14.53qtl/cmh during January and minimum of12.78qtl/cmh during June. In general, the weight of logs was low during summers and high during winter and rainy season. Weight of logs decreased from February onward and increased from August onward. This variation in weight was due to the water content in logs which was as high as 1.75qtl/cmh in January in comparison to that in June (Figure 2).

Figure 2:Monthly variation in matchwood weight (qtl/cmh) (left) and additional water weight in logs during different months with reference to June weight/cmh (right). Logs traded during June were 1.75qtl lighter in weight and less in sale value compared to January sale of same volume.

Moisture content found in green timber can vary between 30% and 250% [37]. The weight of wood depends on its MC besides wood density and some other traits. The main reason for low MC in poplar wood could be associated with high temperature and low humidity in hot weather. The standard reference of MC for wood elements is corresponding to an environment that has a temperature of 20 ℃ and 65% relative humidity [37]. Poplar growing region seldom witness >40 ℃ temperature and between 30-40% relative humidity in summers which brings down the MC in trees as well. According to Borchert [38] stored stem water is also channelized during summers for emergence of leaves and this could be another reason for less moisture content in logs harvested during summers.

There are some studies on MC of logs with different thickness, clones and positions on the main stem. Moisture loss was studied in poplar tradable grade/components for 35 days of harvesting. According to this study the loss in weight of individual components varied from 7.15% in logs over 75cm in mid girth to 11.89% in logs between 60-75cm mid girth, 13.37% in 50-60cm logs, 18.43% in 30.50cm mid girth, 30.5% in roots and 41.65% in firewood. Individual tree components like leaves, foliage, branches etc. on their separation from trees lose MC and weight faster than thick wood logs [34]. Significant clonal variation in wood of 14 commercially grown clones and also in logs made from 1st basal position to 7th sequential log from the main stem was also recorded [11]. Moisture Content on Dry Weight Basis (MCDW) varied from a maximum of 128.34% in WIMCO 81 to a minimum of 83.15% in S7C4 whereas on fresh weight basis (MCFW) it varied from 55.21 in WSL 39 to 45.17% in S7C4.

Conclusion

Poplar is highly sensitive to dehydration, as such, it loves adequate moisture for growing good nurseries and plantations. Its evolution is largely in water surplus river basin ecosystems. Growing its plantations in native and exotic environments is largely dependent on good water availability. However, both excess and deficient water availability slows down its physiological processes, health, growth, productivity, and very survival under extreme conditions. Studies are now focusing on understanding moisture dynamics and its management in poplar production systems. This paper explained MC dynamics in bud sprouts, leaves, and some other components of standing trees and tried to connect it with phonological changes. Leaves exhibit early response to varying moisture levels and regulate it to adjust internal moisture with surrounding environment. The current study provides preliminary findings on MC with some fragmented experiments. A holistic and systematic study may be needed to connect the monthly or seasonal variation in poplar MC along with the surrounding environment conditions to further substantiate these findings. Poplar wood MC is now well appreciated by tree growers for economical returns and by mill engineers for quality peeling. Numerous farmers now prefer harvesting poplar trees during select months when moisture levels are high to realize better wood sale proceeds. Mill engineers try to procure fresh wood on day-to-day basis for peeling moisture saturated logs to produce quality veneers.

References

- Dhiman RC, Gandhi JN, Chander Sekhar (2024) Standard operating activities for poplar based agroforestry. Mod Concep Dev Agrono 14(3): MCDA. 000839.

- Turner NC (1981) Techniques and experimental approaches for the measurement of plant water status. Plant Soil 58: 339-366.

- Poorter H, Bergkotte M (1992) Chemical composition of 24 wild species differing in relative growth rate. Plant Cell Environ 15(2): 221-229.

- Goss JA (2013) Physiology of plants and their cells. Pergamon Press, New York, NY, USA.

- Bowman WD (1989) The relationship between leaf water status, gas exchange, and spectral reflectance in cotton leaves. Remote Sens Environ 30(3): 249-255.

- Agee JK, Wright CS, Williamson N, Huff MH (2002) Foliar moisture content of Pacific Northwest vegetation and its relation to wildland fire behavior. Forest Ecology and Management 167(1-3): 57-66.

- Van Wagner CE (1967) Seasonal variation in moisture content of eastern Canadian tree foliage and the possible effect on crown fires, Canada Department of Forestry and Rural Development, Forestry Branch Departmental Publication 1204, Ottawa, Canada.

- Cao A, Wang Q, Zheng C (2015) Best hyperspectral indices for tracing leaf water status as determined from leaf dehydration experiments. Ecol India. 54: 96-107.

- Zhang C, Liu J, Shang J, Cai H (2018) Capability of crop water content for revealing variability of winter wheat grain yield and soil moisture under limited irrigation. Sci Total Environ 631-632: 677-687.

- Fang M, Ju W, Zhan W, Cheng T, Qiu F, et al. (2017) A new spectral similarity water index for the estimation of leaf water content from hyperspectral data of leaves. Remote Sens Environ 196: 13-27.

- Dhiman RC, Gandhi JN (2024) Clonal variation in moisture content in Populus Deltoides peeling logs. Mod Concep Dev Agrono 14(2): MCDA. 000833.

- Ogbonna CE, Otuu FC, Iwueke NT, Egbu AU, Ugbogu AE (2014) Biochemical properties of trees along Umuahia-Aba Expreessway, Nigeria. International Journal of Environmental Biology 5(4): 99-103.

- Asao S, Hayes L, Aspinwall MJ, Rymer PD, Blackman C, et al. (2020) Leaf trait variation is similar among genotypes of Eucalyptus camaldulensis from differing climates and arises in plastic responses to the seasons rather than water availability. New Phytol 227(3): 780-793.

- Patterson DW, Hartley JI, Stuhlinger HC (2014) Moisture content, specific gravity, and percent foliage weight of cottonwood biomass. Forest Product journal 64(5-6): 206-209.

- Joshi RK, Mishra A, Gupta R, Garkoti SC (2024) Leaf and tree age-related changes in leaf ecophysiological traits, nutrient, and adaptive strategies of Alnus nepalensis in the central Himalaya. J Biosci 49: 24.

- Abdul-Hamid H, Mencuccini M (2009) Age-and size-related changes in physiological characteristics and chemical composition of Acer pseudoplatanus and Fraxinus excelsior Tree Physiol 29(1): 27-38.

- Kenzo T, Inoue Y, Yoshimura M, Yamashita M, Tanaka OA, et al. (2015) Height-related changes in leaf photosynthetic traits in diverse Bornean tropical rain forest trees. Oecologia 177(1): 191-202.

- Poorter H, Bergkotte M (1992) Chemical composition of 24 wild species differing in relative growth rate. Plant Cell Environ 15(2): 221-229.

- Sinha USP, Neog K, Rajkhowa G, Chakravorty R (2003) Variations in biochemical constituents in relation to maturity of leaves among seven mulberry varieties. Sericologia 43(2): 251-257.

- Chaluvachari C, Bongale UD (1995) Evaluation of leaf quality of some genotypes of mulberry through chemical analysis and bioassay with silkworm Bombyx mori L. Indian J Sericult 34: 127-132.

- Poudyal K (2014) Plant water relations and phonological shifts in response to drought in Castanopsis indica at Phulchowki hills, Kathmandu, Nepal. Journal of Biological & Scientific Opinion 2(1):

- Sun Y, Wang H, Sheng H, Liu X, Yao Y, et al. (2015) Variations in internal water distribution and leaf anatomical structure in maize under persistently reduced soil water content and growth recovery after re-watering. Acta Physiol Plant 37(12): 1-10.

- Song X, Zhou G, He Q, Zhou H (2020) Stomatal limitations to photosynthesis and their critical water conditions in different growth stages of maize under water stress. Agric. Water Manage 241: 106330.

- Saura-Mas S, Lloret F (2007) Leaf and shoot water content and leaf dry matter content of Mediterranean woody species with different post-fire regenerative strategies. Ann Bot 99(3): 545-554.

- Brian T, Maarten Nieuweahuis (2007) Biomass expansion factors for Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.) in Ireland. Eur J Forest Res 126:189-196.

- Kozlowski TT, Clausen JJ (1966) Shoot growth characteristics of heterophyllous woody plants. Canadian Journal of Botany 44(6): 827-843.

- Dhiman RC (2010) Weight loss in poplar wood under open conditions and its economical impact. Timber Development Association of India 56: 1-6.

- Al-Sagheer A, Devi Prasad AG (2010) Variation in wood specific gravity, density and moisture content of Dipterocarpus indicus (Bedd) among different populations in Western ghats of Karnataka, India. International Journal of Applied Agricultural Research 5(5): 583-599.

- Isebrands JG, Richardson J (2014) Poplars and Willows. Trees for Society and the Environment. CAB International and FAO, Rome.

- Stanturf JA, Van Oosten C, Netzer DA, Coleman MD, Portwood CJ (2001) Ecology and silviculture of poplar plantations. Poplar Culture in North America, Part A: 153-206.

- Dhiman RC (2012) Unorthodox asexual means for mass multiplication of poplars. Newsletter of the International Poplar Commission 1: 6-8.

- Farrant JM, Cooper K, Hilgart A, Abdalla KO, Bentley J, et al. (2015) A molecular physiological review for vegetative desiccation tolerance in the resurrection plant Xerophyta viscose (Baker). Plaatna 242(2): 407-426.

- USDA (1960) Plant Vigor Criteria. Technical Note. Natural Resources Conservation Service, Department of Agriculture, Range Note No. 18- Arizona, USA.

- Dhiman RC, Gandhi JN (2017) Over storage of poplar (Populus deltoides) saplings affects their field performance. Indian Forester 143(11): 1112-1119.

- Dhiman RC and Singh J (1995) Slurry dips for Populus deloides G3 stem cuttings for improving their storage life in collection-nursery planting phase. In: Khurana DK (Ed.), Poplars in India Recent Research Trends, IDRC-UHF, pp. 57-64.

- Benye Xi, Brent Clothier, Mark Coleman, Jie Duan, Wei Hu, et al. (2021) Irrigation management in poplar (Populus spp.) plantations: A review. Forest Ecology and Management 494: 119330.

- Teodorescu I, Erbașu RJ, Branco M, Tăpuși D (2021) IOP Conf Ser. Earth Environ Sci 664: 012017.

- Borchert R (1994) Soil and stem water storage determines phenology and distribution of tropical dry forest trees. Ecology 75(5): 1437-1449.

© 2024 RC Dhiman. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)