- Submissions

Full Text

Investigations in Gynecology Research & Womens Health

Cervical Cerclage as a Preventive Strategy for Preterm Birth due to Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI). A Narrative Review

Alfredo Ovalle S1,2*

1 Service of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Neonatology, San Borja Arriarán Clinical Hospital, Chile

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Chile, Chile

*Corresponding author:Alfredo Ovalle, Service of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Neonatology, San Borja Arriarán Clinical Hospital, Chile and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Chile, Santiago, Chile

Submission:November 04, 2025;Published: December 16, 2025

ISSN: 2577-2015 Volume5 Issue5

Abstract

Spontaneous Preterm Birth (SPB) is the most common form of Preterm Birth (PB). Although historically linked to cervical insufficiency, Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI) is now the most frequent cause of SPB before 34 weeks, driven by vaginal dysbiosis and cervical inflammation. Vaginal dysbiosis, characterized by the loss of protective Lactobacillus and the predominance of bacteria such as Gardnerella or Prevotella, triggers a local inflammatory response with the release of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and metalloproteinases (MMP-8, MMP-9). These factors degrade the extracellular matrix of the cervix and promote pathological cervical ripening. Pathogens like Streptococcus agalactiae and Escherichia coli also release enzymes that degrade the cervical matrix and trigger SPB. Cervical cerclage, traditionally for mechanical issues, offers a dual benefit: An anatomical barrier against microbial ascent and a modulator of local inflammation. Experimental studies show it prevents intrauterine infection and reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines. Clinical research demonstrates a lower incidence of SPB and histological chorioamnionitis in women with a history of SPB due to ABI who receive preventive cerclage in the first trimester. Using monofilament suture is recommended to better preserve the vaginal microbiome. Cerclage is emerging as a comprehensive, personalized strategy to prevent PB linked to ascending cervicovaginal infection and inflammation.

Keywords:Ascending bacterial infection; Spontaneous preterm labor; Cerclage and ascending infection

Introduction

Preterm Birth (PB), defined as delivery before 37 weeks of gestation, is the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality and the primary contributor to infant mortality worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights the magnitude of this public health problem, estimating that more than 13 million preterm infants are born each year globally, making it the greatest challenge to child survival after the first month of life [1]. SPB the focus of this review, is a syndrome resulting from multiple pathological processes and represents the main cause of PB [2]. Historically, research on SPB has focused on cervical insufficiency and shortening as the primary triggers. However, in settings with a high prevalence of infections and limited economic resources, as documented in Chile and several regions worldwide [2-4], Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI) has been identified as the most frequent etiologic factor of SPB, particularly in cases occurring before 34 weeks of gestation [3,5]. ABI, which includes Bacterial Vaginosis (BV), Aerobic Vaginitis (AV), and Urinary Tract Infections (UTI), establishes a direct link between local inflammation and the onset of preterm labor [3-6].

This concept has been supported by recent experimental studies in animal models, in which ascending vaginal infection induced PB and neonatal morbidity [7]. In addition to inflammation, pathogens such as Group B Streptococcus (GBS) secrete enzymes that degrade essential components of the cervical Extracellular Matrix (ECM), promoting shortening and dilation [8]. This etiological understanding has prompted the development of preventive strategies for SPB that address infection and subclinical inflammation [9]. In this context, cervical cerclage -a surgical procedure traditionally used to improve the mechanical support of the cervix in cases of cervical insufficiency (history of recurrent PB and cervical shortening) [10]- emerges as an intervention with potential benefits beyond mechanical reinforcement. Despite being a commonly used therapy for PB prevention, its exact mechanism of efficacy remains under debate.

Recent research provides strong support for the hypothesis that cerclage may prevent preterm birth associated with ABI. Experimental studies in animal models with induced ABI suggest that cerclage may act as an effective barrier against bacterial ascent, reducing the risk of intrauterine infection, the subsequent inflammatory cascade, and adverse outcomes [11]. Similarly, in pregnant women with cervical insufficiency, cerclage has been shown to decrease inflammation in cervicovaginal secretions [12]. The objective of this narrative review is to synthesize current evidence on the efficacy of cervical cerclage as a preventive strategy specifically targeting preterm birth associated with ABI, by analyzing the pathophysiology of ABI, the mechanisms of action of cerclage (mechanical, anti-inflammatory, and effects on bacterial virulence factors), and discussing the clinical implications of the choice of technique and timing of intervention.

Methods

For this review, a comprehensive bibliographic search was conducted for articles including the following key terms: “Ascending bacterial infection,” “Spontaneous preterm birth,” and “Cerclage and ascending infection.” The search was performed in the following databases: PubMed, Elsevier, Science Direct, Wiley, Scopus, Ovid, and Scielo. Only articles published from 1995 onward were considered.

Review: Kinetics of Ascending Bacterial Infection

The study by Spencer et al. [13] is crucial for understanding the kinetics of microbial invasion and intra-amniotic inflammation, using a murine model of active ascending infection with live E. coli bacteria. The study demonstrated that vaginal administration of E. coli in pregnant mice induces Early Preterm Birth (EPB) in a dose-dependent manner -higher doses resulted in shorter latency to delivery. Using imaging and culture techniques, the authors confirmed that infection is an ascending and gradual process, spreading from the cervix to proximal and then distal gestational tissues, invading the amniotic fluid within 24 hours. This invasion triggered a localized inflammatory response, with increased expression of key markers such as TLR-4 and P-NF-κB in fetomaternal tissues. Notably, the model successfully replicated the ascending route of infection without causing maternal bacteremia. Furthermore, a sub-study validated that early antibiotic intervention with gentamicin could prolong gestation [13].

Pathophysiology of Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI)

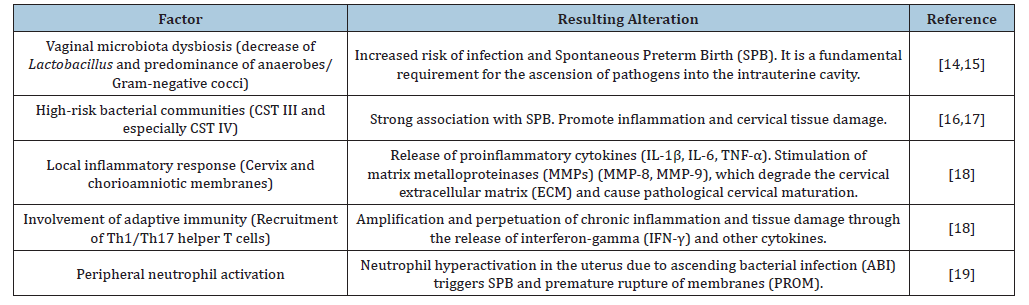

ABI represents a key etiologic pathway in Spontaneous Preterm Birth (SPB), acting through cervical degradation, membrane rupture, and induction of uterine contractility. The pathogenesis of ABI is a complex process involving a bidirectional interaction between the maternal host response (host-dependent factors) and the virulence characteristics of the causal microorganisms (pathogen-dependent factors) (Table 1).

Table 1:Host-dependent factors in the pathophysiology of ascending bacterial infection.

Host-dependent factors: In the pathogenesis of ABI, the main host-dependent factors that mediate the vaginal microbiota and inflammatory response include:

A. Vaginal microbiota dysbiosis: The presence of a nonoptimal vaginal microbiota (dysbiosis), characterized by a decrease in protective Lactobacillus species and a predominance of anaerobic bacteria and/or Gram-negative cocci (as in Bacterial Vaginosis [BV] or Aerobic Vaginitis [AV]), increases the risk of infection and preterm birth. Dysbiosis is a fundamental prerequisite for the ascent of pathogens into the intrauterine cavity [14,15]. Earlier culture-based studies observed that pregnant women with BV have a higher risk of EPB compared to healthy women, with intrauterine infection being a major cause of preterm labor. Although culture remains the gold standard for infection diagnosis, its technical and environmental limitations often hinder the detection of pathogens with special or novel growth requirements [14,15].

B. Specific and persistent vaginal microbiota composition and SPB: Specific vaginal bacterial community types (CST III and especially CST IV), identified through high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, are associated with EPB [16]. The large-scale cohort study by Fettweis et al. [17] established that preterm birth is strongly associated not only with the absence of dominant Lactobacillus species but also with the presence and persistence of specific bacterial communities. CST IV, characterized by a polymicrobial composition with low or absent Lactobacillus dominance, is the group most strongly associated with preterm birth. Its key microbial markers include BV-associated anaerobes such as Gardnerella, Sneathia, Prevotella, and Megasphaera. CST III, dominated by Lactobacillus iners, showed a lower risk than CST IV, suggesting that dominance by L. iners is less protective than that of other species such as L. crispatus and L. gasseri. The study demonstrated that persistence of the high-risk CST (CST IV) throughout pregnancy is the strongest predictor of SPB [17].

C. Microbiome, inflammation, and cervical tissue damage: High-risk communities (CST III and CST IV) are associated with metabolic pathways that promote inflammation, cervical tissue damage, and EPB. In the presence of ascending pathogens, the cervix and chorioamniotic membranes release proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α). Sustained inflammation stimulates the secretion of Matrix Metalloproteinases (MMPs), particularly MMP-8 and MMP-9, by invading microorganisms, which degrade the protective mucosal layer and key components of the cervical Extracellular Matrix (ECM), such as collagen and elastin. This degradation facilitates ascending infection and pathologic cervical maturation [18].

A crucial cross-talk between innate and adaptive immune responses in the cervix has been demonstrated:

a. Involvement of adaptive immunity (T Cells): Recruitment of Th1/Th17 Cells: The danger signals from IL- 1β and other innate cytokines trigger the recruitment of specific types of white blood cells-helper T cells (Th1 and Th17). These lymphocytes are recruited from the systemic immune system to the cervix [18].

b. Amplification of chronic inflammation: Once in the cervix, Th1/Th17 cells release interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and other proinflammatory cytokines. This adaptive immune signaling amplifies and perpetuates the innate inflammatory response, creating a cycle of chronic inflammation and tissue injury that ensures progression toward PB, even if the initial bacterial load decreases. This finding underscores that microbially driven SPB is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease of the cervix. The presence of these dysbiotic communities is associated with a chronic inflammatory profile in the genital tract, consistent with activation of the host’s innate immune response [18].

c. Peripheral neutrophil activation in Preterm Birth (PB): Neutrophils, the most abundant polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the blood, are key effectors of innate immunity and combat infection through cell-death mechanisms. Upon activation, these cells secrete several proinflammatory molecules (such as proteases and cytokines) and labor-promoting mediators (COX- 2 and PGE2), which are necessary to complete the physiological changes of normal labor (uterine contractions, cervical dilation, and rupture of membranes). Despite their protective role, in cases of microbially induced PB, evidence suggests that premature infiltration and hyperactivation of neutrophils in the uterus, cervix, and fetal membranes are key factors likely triggering both PB and premature rupture of membranes (PROM) [19].

d. Altered immune response: Some susceptible pregnant women may exhibit an immune profile prone to excessive inflammation or, conversely, a deficiency in localized antimicrobial response, facilitating persistent colonization and bacterial ascent.

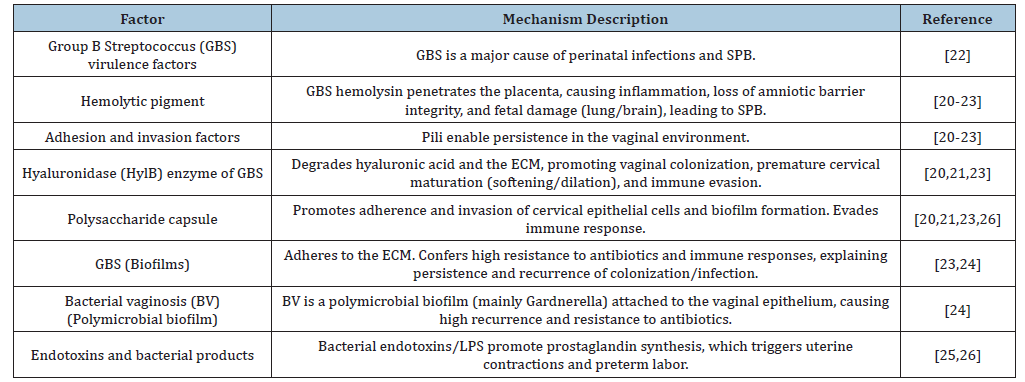

Pathogen-dependent factors: The pathogens associated with Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI) not only trigger an inflammatory response but also possess active virulence mechanisms that damage maternal-fetal structures (Table 2).

Table 2:Pathogen-dependent factors in the pathophysiology of ascending bacterial infection.

Abbreviations: SPB: Spontaneous Preterm Birth; CST: Community State Type; MMP: Matrix Metalloproteinase; ECM: Extracellular Matrix; PROM: Premature Rupture of Membranes.

A. Virulence factors of Group B Streptococcus (GBS): Group B Streptococcus Streptococcus agalactiae) is a leading cause of perinatal infections and preterm birth. Its virulence factors enable colonization of the genital tract and ascending infection. These include:

a) Hemolytic pigment: Hemolysin facilitates GBS penetration of the placenta and loss of barrier function in amniotic cells. It triggers inflammatory responses leading to preterm labor and confers resistance to elimination by Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs). This contributes to GBS dissemination in uterine, placental, and fetal tissues and forms pores in the cytoplasmic membrane of fetal organs such as the lungs and brain, resulting in adverse outcomes [20-22]. Granadaene is a pigment that invades the placenta and fetus with severe consequences [23].

b) Adhesion and invasion factors: These factors promote persistence in the vaginal environment, such as pili structures that mediate adhesion and colonization [20-23].

c) Hyaluronidase (HylB): This enzyme promotes vaginal colonization by degrading host hyaluronic acid and evading the immune response through inhibition of TLR2/TLR4 signaling. It contributes to cervical maturation by degrading the Extracellular Matrix (ECM), particularly proteoglycans and hyaluronic acid [20,21,23], leading to softening, shortening, and premature cervical dilation (cervical remodeling).

d) Polysaccharide capsule: This capsule promotes adhesion and invasion of cervical epithelial cells [20] and biofilm formation [23] while enabling immune evasion [21]. Moreover, hypervirulent ST-17 strains (serotype III) show a greater tendency to cause neonatal meningitis and are associated with increasing antibiotic resistance [21].

e) Understanding these virulence factors is fundamental for developing new therapies and vaccines against GBS.

B. Biofilm formation: Many microorganisms in the lower genital tract form biofilms, bacterial communities embedded within a protective matrix. This structure provides pathogens with high resistance to antibiotics and host immune defenses, facilitating their persistence and gradual ascent.

a) GBS and biofilm formation: GBS can form biofilms, communities of bacteria adhering to the extracellular matrix, enhanced by the polysaccharide capsule and pili. Biofilm formation is a major virulence factor explaining GBS persistence, recurrent colonization, and difficulty eradicating infection with antibiotics Liu [23]. GBS biofilms are a key mechanism of persistent colonization in the genital and gastrointestinal tracts. Within this extracellular matrix, GBS is shielded from host defenses and antibiotic therapy, complicating eradication even with intrapartum prophylaxis. Factors such as the polysaccharide capsule and adhesins (e.g., pili) facilitate the formation of this structure, increasing the risk of neonatal transmission.

b) Polymicrobial biofilm in Bacterial Vaginosis (BV): The study by Swidsinski [24] redefined BV from a simple dysbiosis (microbiota imbalance) to a polymicrobial biofilm infection. This biofilm is structurally dominated by Gardnerella spp. and adheres directly to the vaginal epithelium. Formation of this community structure is key to the high recurrence rate of BV (over 50%), as the extracellular matrix protects bacteria from standard antibiotics such as metronidazole. Additionally, epithelial cells covered by the biofilm, known as clue cells, act as ideal vectors for sexual transmission of the infection, underscoring its contagious nature [24].

C. Induction of Uterine Contractility: Endotoxins and other bacterial products (such as lipopolysaccharides, LPS) that reach the uterine cavity promote prostaglandin synthesis (PGE2 and PGF2α) in the amnion and decidua [25]. Moreover, GBS strains expressing HylB induce invasion of the amniotic cavity, prostaglandin synthesis, and PB, in contrast to mutant strains lacking the enzyme [26]. Prostaglandins are the final mediators that trigger uterine contractions and labor.

Dysbiosis in Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

Recurrent Urinary Tract Infection (UTI), like vaginal infections, is associated with dysbiosis of the urinary microbiome (uromicrobiome). This supports the inclusion of UTI within the ABI framework, suggesting that urinary infection also originates from microbial imbalance rather than solely from exogenous infection. The immunological microenvironment of the urothelium (bladder lining) shows that dysbiosis induces chronic local inflammation characterized by activation of immune cells such as T cells and mast cells. This connection between UTI and the inflammatory cascade suggests a common pathophysiological mechanism: dysbiosismediated inflammation. Furthermore, dysbiosis compromises the epithelial barrier integrity and the innate immune response of the urothelium. Therefore, the risk of preterm birth associated with UTI is not only due to the bacterial presence but also to the local or systemic inflammation caused by microbial imbalance during pregnancy. This study reinforces the concept that dysbiosis-whether vaginal (BV/AV) or urinary (UTI)-underlies the inflammatory pathology capable of triggering preterm birth [27].

Intrauterine inflammation and infection as a risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes

Research using animal models has provided a solid foundation for understanding the pathogenesis of Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI) and its perinatal consequences. These models have demonstrated that intrauterine inflammation, regardless of the causal pathogen, is a key determinant of Preterm Birth (PB) and fetal organ injury.

Escherichia coli and Induction of the Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome (FIRS): The study by Boyle et al. [7] used a murine model of ascending vaginal infection with Escherichia coli to demonstrate that ABI induces PB and significantly increases neonatal morbidity and mortality. The main mechanism identified was the Fetal Inflammatory Response Syndrome (FIRS). Maternal infection triggers a systemic inflammatory response in the fetus, evidenced by elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines primarily TNF-α and IL-6-in the amniotic fluid and fetal serum. This systemic inflammation not only induces labor but also causes severe and irreversible organ damage in premature offspring. This animal model is crucial, as it shows that infection, induced neonatal injury is not solely due to fetal immaturity but results from the direct action of intrauterine inflammation on fetal organs. Therefore, these findings highlight the need to develop therapies aimed not only at controlling the pathogen but also at modulating the fetal inflammatory cascade, through strategies such as TNF-α or IL-6 blockade, to reduce organ injury and protect the fetus.

Intrauterine inflammation as a risk factor for neonatal brain injury: Another experimental murine study reinforced the association between intrauterine inflammation and neonatal neurological damage. Using bioluminescent E. coli strains, ascending infection was tracked in real time in pregnant mice. Two strains were compared: K12 (nonpathogenic) and K1 (highly pathogenic). Both ascended from the vagina to the uterus; however, only E. coli K1 induced PB and reduced neonatal survival. Importantly, both strains-even the nonpathogenic one-increased expression of inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6) in the uterus, fetal membranes, and placenta, demonstrating a strong intrauterine inflammatory response. The most striking finding was that viable offspring of mothers infected with either strain exhibited significant cerebral inflammation on postnatal day six, evidenced by increased IL-1β in the brain, microglial activation, and cortical cell death. These results indicate that intrauterine exposure to bacteria, even those of low virulence, can induce an inflammatory response responsible for neonatal brain injury, independent of gestational age at delivery [28].

Intrauterine infection, preterm birth, and adverse neonatal outcome: A non-human primate model (Macaca nemestrina) enabled the study of the role of the hyaluronidase enzyme (HylB) from Group B Streptococcus agalactiae (GBS) in the pathogenesis of PB and adverse neonatal outcomes. It was shown that GBS strains expressing HylB induce invasion of the amniotic cavity, fetal bacteremia, and PB, in contrast to mutant strains lacking the enzyme. The results revealed that HylB interferes with maternal immune defenses by impairing neutrophil function and attenuating TLR-2 and TLR-4 receptor signaling in the inflammatory response. Despite mild placental inflammation, infected animals exhibited elevated levels of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-1 and MMP- 3) and prostaglandins, suggesting an alternative mechanism for cervical maturation and labor initiation. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that bacterial hyaluronidase acts by evading the immune response, facilitating intra-amniotic colonization without triggering intense inflammation, yet still leading to PB and fetal injury. This study provides critical evidence on how a single virulence factor can disrupt the immunological balance of pregnancy and compromise perinatal outcomes [26].

Cervical incompetence and ascending bacterial infection

Early mechanical failure of the cervix -known as cervical maturation- characterized by softening, shortening, and premature dilation, represents the final common pathway in all causes leading to Spontaneous Preterm Birth (SPB). This failure involves a complex remodeling process of the Extracellular Matrix (ECM), in which the cervical tissue transitions from a rigid, load-bearing structure to a soft, compliant one.

Altered cervical microbiome in the pathogenesis of Cervical Incompetence (CI): The role of the cervical microbiome in the pathogenesis of Cervical Incompetence (CI) was investigated using 16S rRNA metagenomic sequencing of cervical mucus obtained from women with CI before and after cerclage placement. The study revealed that women with pre-cerclage CI (PreOp) exhibited reduced vaginal abundance of Lactobacillus spp. and greater colonization by Gardnerella spp. and Prevotella spp. compared with Post-Cerclage (PostOp) samples, indicating dysbiosis associated with the condition. In vitro experiments demonstrated that supernatants from Group B Streptococcus (GBS) cultures promoted a significant inflammatory response in cervical epithelial cells, increasing the expression of Toll-Like Receptors (TLRs) and the transcription factor NF-κB, activation closely linked to ECM degradation and the onset of cervical ripening. Furthermore, costimulation of cervical epithelial cells with Lactobacillus crispatus and GBS resulted in a reduced inflammatory response, suggesting an immunomodulatory role of L. crispatus [29].

Abnormal vaginal microbiota in patients with cervical incompetence: The impact of Escherichia coli: The retrospective study by Choi et al. [30], involving 138 pregnant Korean women diagnosed with cervical incompetence, highlighted a critical adverse association: The frequent presence of abnormal vaginal flora, particularly colonization by Escherichia coli. The study reported that 61% of patients had abnormal bacterial colonization in the upper vagina, with E. coli being the most prevalent pathogen (33%). Vaginal colonization by E. coli was linked to a higher-risk clinical profile, including a greater rate of previous PB (26.1% vs. 10.9%) and an earlier diagnosis of cervical incompetence (20.7 vs. 22.3 weeks). The E. coli-positive group experienced markedly worse obstetric and neonatal outcomes, with significantly higher rates of clinical chorioamnionitis (21.7% vs. 6.5%). Neonatal consequences were severe, showing increased incidences of Early-Onset Neonatal Sepsis (EONS) (17.4% vs. 6.5%; adjusted OR=3.853), Necrotizing Enterocolitis (NEC) (15.2% vs. 1.1%; adjusted OR=12.410), and neonatal mortality (17.4% vs. 5.4%). Placental pathology revealed a greater frequency of subchorionic microabscesses (26.1% vs. 9.8%) among E. coli-positive cases, indicating an acute and severe inflammatory response. This study underscores the need to consider E. coli as a key vaginal pathogen in patients with symptomatic cervical incompetence, given its strong association with serious neonatal morbidity and mortality [30].

Importance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with cervical insufficiency: The study by Lee et al. [31] focused on determining the frequency and significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with cervical insufficiency. A high proportion (81%) of women with acute cervical insufficiency (≥1.5cm cervical dilation, intact membranes, and no regular uterine contractions) presented intra-amniotic inflammation, even in the absence of overt infection (amniotic fluid infection rate: 8%). This inflammatory process, characterized by elevated matrix metalloproteinase-8 (MMP-8> 23ng/mL), even when sterile, represents an independent risk factor for preterm birth and poor neonatal outcomes. Amniotic fluid analysis -including IL-6 levels, Gram stain, and MMP-8 concentration- is critical for differentiating between infectious and sterile intra-amniotic inflammation. This distinction is fundamental for clinical decision-making, such as whether to perform a cerclage, since severe intra-amniotic inflammation (e.g., IL-6≥3000pg/mL) correlates with a shorter latency to delivery. The authors concluded that, in patients with cervical insufficiency, intra-amniotic inflammation has prognostic value and constitutes a risk factor for PB and adverse neonatal outcomes, independent of intrauterine infection [31].

Altered vaginal microbiota in recurrent spontaneous preterm birth: This prospective cohort study investigated the relationship between the vaginal microbiota and the risk of recurrent Spontaneous Preterm Birth (SPB) in 152 pregnant women with a prior history of preterm delivery, between 16 and 27 weeks of gestation. Vaginal samples were collected before 16 weeks and again between 16-24 weeks for 16S rRNA sequencing. Fiftythree women (34.9%) experienced recurrent SPB. Lactobacillus iners predominated among recurrent cases, whereas L. crispatus was more frequent among non-recurrent ones. Community State Types (CSTs) III and IV were associated with early and late PB, respectively, while CST I predominated in the non-recurrent group. The study concluded that a predominance of L. iners before 16 weeks is linked to an increased risk of recurrent SPB, reflecting an unfavorable vaginal environment deficient in protective Lactobacillus species [32].

Systemic Risk Factors and Ascending Infection

Pregnant women with risk factors such as diabetes [33], obesity [34], chronic stress [35,36], autoimmune diseases [37], chromosomal abnormalities [38], and HIV infection [39], often associated with Bacterial Vaginosis (BV) and immune dysregulation, show an increased presence of cervicovaginal neutrophils, proinflammatory cytokines, and complement cascade activation. These factors make them more prone to Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI), leading to Spontaneous Preterm Birth (SPB) and its consequences. This concept is central in modern obstetrics, emphasizing that maternal systemic comorbidities act as gateways to local dysfunction of the Lower Genital Tract (LGT). Conditions such as diabetes [33] and obesity [34] are not merely metabolic disorders; they behave as chronic proinflammatory states. Obesity induces systemic low-grade inflammation mediated by adipokines such as IL-6 and leptin. Similarly, chronic stress [35,36], together with autoimmune diseases [37] and immunosuppression associated with viral infections such as HIV [39], impair local protective mechanisms. Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, which inhibit the proliferation of Lactobacillus spp. This disturbance in lower genital tract homeostasis often manifests as Bacterial Vaginosis (BV), characterized by a reduced abundance of Lactobacillus spp. and high bacterial diversity [35,36]. Sustained inflammation and subsequent maternal immune dysregulation disrupt the delicate equilibrium of the vaginal microbiome, increasing susceptibility to ascending infection and PB.

Cervical Cerclage

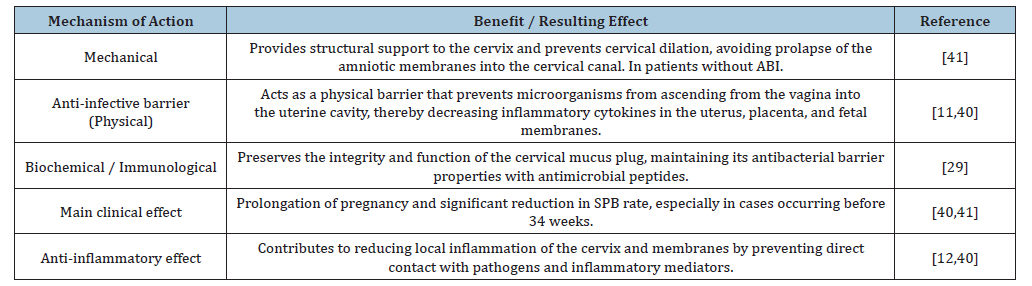

Cervical insufficiency is a major cause of second-trimester pregnancy loss and Preterm Birth (PB). Cervical cerclage, the standard surgical intervention, has traditionally been viewed as a means of mechanical support, a concept that has evolved with recent publications (Table 3).

Table 3:Cervical Cerclage: Benefits and mechanisms of action.

Abbreviations: ABI: Ascending Bacterial Infection; SPB: Spontaneous Preterm Birth.

Cerclage enhances the cervical physical barrier and reduces local inflammation in mice

In murine models, abdominal cerclage not only prevented intrauterine infection but also inhibited the expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes [11]. This finding is crucial because it establishes a dual mechanism of action: cerclage acts as a physical barrier while also modulating the local inflammatory response. Traditionally, the mechanical support provided by cerclage has been considered the mechanism by which it prevents PB. However, Zhang et al. [11] demonstrated in an animal model that cerclage enhances the physical barrier function of the cervix, resulting in decreased ascending intrauterine infection and associated inflammation. A murine model of ascending infection was used. Pregnant mice received abdominal cerclage, and bioluminescent Escherichia coli (E. coli K12-lux) were administered to track bacterial ascension in real time through imaging techniques. In control mice without cerclage, the bioluminescent signal ascended to the uterine horns within 24 hours. In contrast, in mice with abdominal cerclage, no ascending signal was detected in the uterus, placenta, or fetal membranes-demonstrating that cerclage physically prevented bacterial invasion into the uterine cavity through the cervix. Furthermore, using the pathogenic E. coli K1 strain, cerclage placement significantly reduced the expression of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 in the uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes compared with infected controls. These findings strongly support that cerclage prevents PB, at least in part, by reducing intrauterine infection and subsequent inflammation. This study provides experimental evidence that cerclage strengthens the cervical barrier mechanism, suggesting that the anatomical compression exerted by the suture improves the protective function of the cervix [11].

Cervical cerclage decreases local levels of proinflammatory cytokines in patients with cervical insufficiency

Compared with normal pregnancies, patients with cervical insufficiency (diagnosed based on history) show elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, MCP-1, and TNF-α in Cervicovaginal Fluid (CVF), but not in serum, before cerclage placement, suggesting local immune dysregulation [12]. After vaginal cerclage placement, a significant reduction in these proinflammatory cytokines was observed in CVF, indicating that cerclage may help reduce local inflammation in cervical insufficiency, a key mechanism implicated in intra-amniotic infection and PB. This study helps explain how cerclage functions in women with a history of prior PB to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Cervical cerclage reduces preterm birth due to ascending bacterial infection and histological chorioamnionitis

Clinical evidence in humans remains limited because of the difficulty of conducting randomized studies in populations with this specific etiology [40]. However, a chilean prospective cohort study provides valuable preliminary evidence. It included women with singleton pregnancies and a history of SPB <34 weeks due to ABI (defined by urinary or cervicovaginal infection during gestation, histological chorioamnionitis/funisitis, and infectious perinatal morbidity/mortality). Prophylactic cerclage performed in the first trimester-compared with a non-cerclage control group with cervical length >25 mm in the second trimester-reduced the incidence of PB (<37 and <34 weeks) and histological chorioamnionitis. Despite its small sample size (23 and 28 patients with and without cerclage, respectively), which is a limitation of the study, the rigorous identification of a homogeneous population at risk of ABI: Women with a history of SPB due to ABI (mean 1.5 per patient), confirmed by chorioamnionitis or placental funisitis and infectious cause perinatal mortality/morbidity (mean 1.5 and 0.5 per patient, respectively), constitutes a solid strength [6,9]. Furthermore, cerclage surgery, obstetric management, and placental analysis were all performed by a single operator. Although preliminary, these results are highly suggestive and challenge the traditional view that restricts cerclage to cases of cervical insufficiency. By demonstrating a reduction in histological chorioamnionitis, the study suggests that first-trimester cerclage may decrease infection and inflammation in both the cervicovaginal environment and the amniotic cavity, by shortening the duration of exposure to ABI. Consequently, these findings point toward a promising future in improving perinatal outcomes [40].

Based on the evidence presented, the procedure of choice for patients with a history of SPB associated with ABI should be prophylactic vaginal cerclage performed in the first trimester [9,40]. Waiting for cervical shortening (US <25mm) or acute cervical insufficiency to indicate cerclage reduces both its mechanical and immunomodulatory efficacy, favoring vaginal dysbiosis [29,30] and increasing the likelihood of intra-amniotic infection/inflammation [31]. Transabdominal cerclage should not be considered a first-line option unless there is severe cervical damage or previous failure of vaginal cerclage. Vaginal cerclage is less invasive and, according to current evidence, achieves the therapeutic goals of containing infection and modulating the inflammatory response.

Cervical cerclage reduces preterm birth based on ultrasound indication

The meta-analysis by Berghella et al. [41] provides clear evidence supporting the use of cerclage based on ultrasound indication. This analysis, which included five randomized controlled trials, concluded that cerclage is significantly beneficial in singleton pregnancies with a history of spontaneous PB and cervical length <25mm before 24 weeks, without prior ABI. The intervention significantly reduced PB <35 weeks (RR 0.70) and composite perinatal morbidity and mortality (RR 0.64) [41]. This meta-analysis has major clinical implications: It provides a solid evidence base supporting the replacement of history-indicated cerclage (based solely on obstetric history) with ultrasoundindicated cerclage in high-risk populations.

Suture Material for Cerclage

Traditionally, both monofilament and braided multifilament sutures have been used for cerclage, with the latter being more common despite the lack of supporting evidence. A large clinical study by Kindinger et al. [42] evaluated outcomes in 678 women who underwent cerclage using both types of sutures. The findings were striking: braided sutures were associated with a significantly higher risk of PB and intrauterine death compared with monofilament sutures. To elucidate the mechanism, a prospective longitudinal study of the vaginal microbiome in 49 women at risk of PB revealed that braided sutures induced a persistent shift toward vaginal dysbiosis, characterized by reduced Lactobacillus spp. and enrichment of pathobionts. This dysbiosis correlated with increased proinflammatory cytokine excretion and premature cervical remodeling. In contrast, monofilament sutures had minimal impact on the microbiome and host interactions. These data suggest that suture material selection is critical, as the dynamic shift toward dysbiosis induced by braided sutures is associated with a higher risk of PB and adverse fetal outcomes [42].

Discussion

Preterm Birth (PB), a multifactorial condition, remains the most significant challenge in modern obstetrics and is responsible for the majority of global neonatal morbidity and mortality [1]. Over recent decades, accumulating evidence has transformed the understanding of Spontaneous Preterm Birth (SPB) from a purely mechanical phenomenon into a complex infectious and inflammatory process, in which the cervix plays a central role as both an anatomical and immunological barrier. The finding that Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI) represents the principal etiologic pathway of SPB before 34 weeks in several settings (2-4) has redefined preventive strategies. In this context, cervical cerclage, traditionally indicated for mechanical cervical insufficiency [10], acquires a new dimension as a modulator of infection and local inflammation [11,12]. Current knowledge of ABI pathophysiology shows that vaginal dysbiosis, characterized by the loss of protective Lactobacillus species and the predominance of anaerobic bacteria such as Gardnerella, Prevotella, or Sneathia, constitutes a prerequisite for bacterial ascension [14,17]. This disturbance of the vaginal ecosystem triggers a cervical inflammatory response, with elevated proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-8, MMP-9) that degrade the cervical ECM [18]. Simultaneously, pathogens such as Streptococcus agalactiae express virulence factors-including hyaluronidase, hemolysin, and capsular polysaccharides-that facilitate tissue invasion and premature cervical remodeling [20,21,23,26]. This inflammatory milieu, exacerbated by interactions between the innate and adaptive immune systems, culminates in early cervical shortening and dilation, facilitating PB.

During intrauterine infection, fetal and neonatal health are compromised by bacterial virulence mechanisms, mediated through invasion factors, toxins, and immune evasion, resulting not only in direct tissue injury, but also in a severe inflammatory response that critically increases the risk of severe infectious morbidity and long-term neurological sequelae [7,20,26,28]. Vaginal microbial dysfunction, particularly Bacterial Vaginosis (BV), and the associated risk of PB [15] can be exacerbated by maternal stress [36], ethnic differences [35], chronic diseases such as diabetes [33] and obesity [34], as well as genetic polymorphisms [38].

Within this infection-dominant etiologic framework, cervical cerclage acquires a novel therapeutic dimension by interrupting the vicious cycle of infection-inflammation-cervical remodeling. The most compelling experimental evidence comes from the murine model developed by Zhang et al. [11], who demonstrated that abdominal cerclage prevented E. coli ascension into the uterine cavity and significantly reduced the expression of inflammatory cytokines in the uterus, placenta, and fetal membranes. In cerclagetreated animals, bacterial bioluminescence did not cross the cervical canal, confirming its role as an effective physical barrier [11]. This finding, of high biological validity, suggests that the anatomical compression produced by the suture restores the cervical sealing function, limiting infection progression.

Beyond its mechanical effect, clinical studies also support an immunomodulatory role for cerclage. Monsanto et al. [12] demonstrated that in women with cervical insufficiency (diagnosed by history), vaginal cerclage placement reduced local levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, MCP-1, and TNF-α) in cervicovaginal fluid (CVF) without altering systemic cytokine profiles. This finding confirms that the effect of cerclage is concentrated within the cervicovaginal microenvironment, contributing to the restoration of local immune homeostasis. By decreasing inflammation, cerclage may limit activation of signaling pathways that promote cervical maturation and premature uterine contractions.

Clinical experience, supported by a study evaluating prophylactic cerclage in women with singleton pregnancies and a history of SPB associated with ABI, shows promising results (40 Ovalle). In patients whose prior SPB had an infectious/inflammatory cause (presence of urinary or cervicovaginal infection during gestation, histological chorioamnionitis/funisitis, and infectious perinatal morbidity/mortality), cervical cerclage reduced both PB <34 weeks and histological chorioamnionitis. In addition to the mechanical and immunomodulatory effects achieved, these results suggest that the key to cerclage efficacy lies in its early, first-trimester placement preventively, before cervicovaginal dysbiosis allows microbial ascension and intra-amniotic infection/inflammation, which would otherwise trigger an irreversible inflammatory cascade. Waiting for the occurrence of sonographic cervical shortening <25mm or acute cervical insufficiency (cervical dilation ≥1.5cm with intact membranes and no regular uterine contractions (before indicating cerclage reduces both the mechanical and immunomodulatory effectiveness of the procedure. This delay promotes vaginal dysbiosis [29,30] and increases the risk of intra-amniotic infection and inflammation [31]. Furthermore, by reducing the incidence of histologic chorioamnionitis, a promising outlook emerges for improving perinatal outcomes [40]. Although the sample size of this study was limited, the homogeneity of the population and the rigorous histological confirmation strengthen the validity of its conclusions.

In women at risk of SPB due to ABI, the suture material used for cerclage should be monofilament. The commonly used braided multifilament suture should be avoided in these cases, as it significantly increases the risk of SPB and fetal death by inducing vaginal dysbiosis and inflammation. In contrast, monofilament sutures exert minimal impact on the vaginal microbiome [42]. It is also important to bear in mind that the normalization of the vaginal microbiota by treating existing vaginal infections or dysbiosis prior to performing the cerclage is a primordial factor to consider for the success of the procedure, especially in the prevention of histological chorioamnionitis and preterm birth due to ABI [43]. Cervical cerclage, when performed preventively and targeted to women with a history of SPB associated with ABI, represents a well-founded and highly promising strategy. Its efficacy extends beyond its mechanical role, encompassing modulation of the local inflammatory response and protection against microbial and enzymatic invasion. This etiologic and personalized approach to cerclage may be essential to reducing the incidence of PTB and potentially perinatal morbidity and mortality, particularly in settings where genitourinary infections are prevalent. With the strength of these results (reduction of histological chorioamnionitis), there is an urgent need to conduct multicenter randomized clinical trials to confirm this assertion and translate this recommendation into globally applicable clinical guidelines.

Conclusion

Spontaneous preterm birth associated with ascending bacterial infection represents a complex clinical challenge, where vaginal dysbiosis, immune-mediated inflammation, and cervical matrix degradation converge. In this context, cervical cerclage emerges as an intervention with a dual action: serving both as an anatomical barrier and a local immunomodulator. Experimental evidence demonstrates that it prevents bacterial ascent and reduces uterine and placental inflammation, while clinical studies corroborate a significant reduction in proinflammatory cytokines within the cervicovaginal microenvironment following its placement. Prophylactic cerclage performed in the first trimester in women with a history of SPB due to ABI is associated with a lower incidence of PB and histological chorioamnionitis, by preventing cervicovaginal dysbiosis that could otherwise lead to microbial ascent and intrauterine infection/inflammation. Additionally, it may promote the restoration of a protective vaginal microbiota dominated by Lactobacillus spp. Collectively, these findings position cerclage as an integrated preventive strategy against PB secondary to ABI, capable of modifying both the mechanical conditions and the immunobiological environment of the cervix.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this review lies in its integrative approach, combining pathophysiological, experimental, and clinical evidence to analyze the role of cervical cerclage in the prevention of PB due to ABI. Unlike previous reviews focused exclusively on mechanical cervical insufficiency, this work delves into the underlying immunological and microbiological mechanisms, providing an updated and biologically coherent perspective that supports the hypothesis of a dual-mechanical and anti-inflammatory-effect of cerclage. Among the main limitations is the scarcity of multicenter randomized clinical trials specifically evaluating cerclage in populations with documented ascending bacterial infection (ABI), as well as the lack of clinical studies analyzing maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with this infection during pregnancy. This gap justifies the present review, which integrates clinical evidence with pathophysiological and experimental foundations. However, this approach faces limitations arising from methodological heterogeneity among studies, variations in surgical techniques and suture materials used, and the absence of longitudinal microbiome analyses-all of which restrict the extrapolation of results. Nevertheless, the consistency between experimental and clinical findings provides strong support for the conclusions presented.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO) Premature births. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ (2014) Preterm labor: One syndrome, many causes. Science 345(6198): 760-765.

- Ovalle A, Kakarieka E, Rencoret G, Sources A, María José R, et al. (2012) Factors associated with preterm birth between 22 and 34 weeks in a public hospital in Santiago. Rev Med Chile 140: 19-29.

- Tantengco OAG, Menon R (2022) Breaking down the barrier: The role of cervical infection and inflammation in preterm birth. Front Glob Womens Health 2: 777643.

- Ovalle A, Kakarieka E, Díaz M, García Huidobro T, Acuña MJ, et al. (2012) Perinatal mortality in preterm birth between 22 and 34 weeks in a public hospital in Santiago, Chile. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol 77: 263-70.

- Ovalle A, Oyarzún E (2024) Vaginal microbiota and immunological profile of pregnant women prone to preterm birth due to ascending bacterial infection. Narrative review. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol 89(3): 164-181.

- Boyle AK, Tetorou K, Suff N, Beecroft L, Mazzaschi M, et al. (2025) Ascending vaginal infection in mice induces preterm birth and neonatal morbidity. Am J Pathol 195(5): 891-906.

- Vornhagen J, Quach P, Boldenow E, Merillat S, Whidbey C, et al. (2016) Bacterial hyaluronidase promotes ascending GBS infection and preterm birth. mBio 7(3): e00781-16.

- Ovalle A, Martínez MA, Figueroa J (2019) Can preterm birth due to ascending bacterial infection and its adverse outcomes be prevented in public hospitals in Chile? Rev Chil Infect 36(3): 358-368.

- Shennan AH, Story L, Royal College of Obstetricians, Gynaecologists (2022) Cervical Cerclage: Green-top Guideline No. 75. BJOG 129(7): 1178-1210.

- Zhang Y, Edwards SA, House M (2023) Cerclage prevents ascending intrauterine infection in pregnant mice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 230(5): 555.e1-555.e8.

- Monsanto SP, Daher S, Ono E, Pendeloski KPT, Évelyn Trainá, et al. (2017) Cervical cerclage placement decreases local levels of proinflammatory cytokines in patients with cervical insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol 217(4): 455.e1-455.e8.

- Spencer NR, Radnaa E, Baljinnyam T, Kechichian T, Tantengco OAG, et al. (2021) Development of a mouse model of ascending infection and preterm birth. PLoS ONE 16(12): e0260370.

- Meis PJ, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, Moawad A, Das A, et al. (1995) The preterm prediction study: Significance of vaginal infections. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol 173(4): 1231-1235.

- Zhao F, Hu X, Ying C (2023) Advances in research on the relationship between vaginal microbiota and adverse pregnancy outcomes and gynecological diseases. Microorganisms 11(4): 991.

- Elovitz MA, Gajer P, Riis V, Brown AG, Humphrys MS, et al. (2019) Cervicovaginal microbiota and local immune response modulate the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. Nat Commun 10(1): 1305.

- Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Brooks JP, Edwards DJ, Girerd PH, et al. (2019) The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. Nat Med 25(6): 1012-1021.

- Chan D, Bennett PR, Lee YS, Kundu S, Teoh TG, et al. (2022) Microbial-driven preterm labour involves crosstalk between the innate and adaptive immune response. Nat Commun 13(1): 975.

- Gimeno-Molina B, Muller I, Kropf P, Sykes L (2022) The role of neutrophils in pregnancy, term and preterm labour. Life (Basel) 12(10): 1512.

- Vornhagen J, Waldorf KMA, Rajagopal L (2017) Perinatal Group B streptococcal infections: Virulence factors, immunity, and prevention strategies. Trends Microbiol 25(11): 919-931.

- Brokaw A, Furuta A, Dacanay M, Rajagopal L, Adams Waldorf KM (2021) Bacterial and host determinants of group B streptococcal vaginal colonization and ascending infection in pregnancy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 11: 720789.

- Ovalle A, Martinez MA (2007) Infection genital. In: Guzman E (Ed). Selection of topics in gynecology and obstetrics. Volume II, Publimpacto Publishing House, Spain, pp. 875-923.

- Liu Y, Liu J (2022) Group B streptococcus: Virulence factors and pathogenic mechanism. Microorganisms 10(12): 2483.

- Swidsinski S, Moll WM, Swidsinski A (2023) Bacterial vaginosis-Vaginal polymicrobial biofilms and dysbiosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 120(20): 347-354.

- Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Hauth JC (2002) Choriodecidual infection and preterm birth. Nutr Rev 60(5 Pt 2): S19-S25.

- Coleman M, Armistead B, Orvis A, Quach P, Brokaw A, et al. (2021) Hyaluronidase impairs neutrophil function and promotes group B streptococcus invasion and preterm labor in nonhuman primates. mBio 12(1): e03115-20.

- Dominoni M, Scatigno AL, Verde ML, Bogliolo S, Melito C, et al. (2023) Microbiota ecosystem in recurrent cystitis and the immunological microenvironment of urothelium. Healthcare (Basel) 11(4): 525.

- Suff N, Karda R, Diaz JA, Ng J, Baruteau J, et al. (2018) Ascending vaginal infection using bioluminescent bacteria evokes intrauterine inflammation, preterm birth, and neonatal brain injury in pregnant mice. Am J Pathol 188(10): 2164-2176.

- Jingwen J, Jingran F, Liye M, Yu H, Yancen M, et al. (2025) The role of cervical microbiome in cervical incompetence: Insights from 16 S rRNA metagenomic sequencing. BMC Microbiol 25(1): 486.

- Choi YS, Kim Y, Hong SY, Cho HJ, Sung JH, et al. (2023) Abnormal vaginal flora in cervical incompetence patients - The impact of Escherichia coli. Reprod Sci 30(10): 3010-3018.

- Lee SE, Romero R, Park CW, Jun JK, Yoon BH (2008) The frequency and significance of intraamniotic inflammation in patients with cervical insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol 198(6): 633.e1-8.

- Jiang X, Bao Y, Li X, Qu X, Mao X, et al. (2025) Characteristics of the vaginal microbiota associated with recurrent spontaneous preterm birth: A prospective cohort study. J Transl Med 23(1): 541.

- Donders GG (2002) Lower genital tract infections in diabetic women. Curr Infect Dis Rep 4(6): 536-539.

- Faucher MA, Greathouse KL, Hastings-Tolsma M, Padgett RN, Sakovich K, et al. (2020) Exploration of the vaginal and gut microbiomecin African American Women by body mass index, class of obesity, and gestational weight gain: A pilot study. Am J Perinatol 37(11): 1160-1172

- Culhane JF, Rauh V, McCollum KF, Elo IT, Hogan V (2002) Exposure to chronic stress and ethnic differences in rates of bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 187(5): 1272-1276.

- Dole N, Savitz DA, Hertz-Picciotto I, Siega-Riz AM, McMahon MJ, et al. (2003) Maternal stress and preterm birth. Am J Epidemiol 157(1): 14-24.

- Bender IRA, Madison AT, Moshiri A, Weiss NS, Mueller BA (2018) A population-based study of perinatal infection risk in women with and without systemic lupus erythematosus and their infants. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 32(1): 81-89.

- Macones GA, Parry S, Elkousy M, Clothier B, Ural SH, et al. (2004) A polymorphism in the promoter region of TNF and bacterial vaginosis: Preliminary evidence of gene-environment interaction in the etiology of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol 190(6): 1504-1508.

- Foessleitner P, Petricevic L, Boerger I, Steiner I, Kiss H, et al. (2021) HIV infection as a risk factor for vaginal dysbiosis, bacterial vaginosis, and candidosis in pregnancy: A matched case-control study. Birth 48(1): 139-146.

- Ovalle A, Valderrama O, Rencoret G, Fuentes A, Río MJ, et al. (2012) Prophylactic cerclage in women with previous spontaneous preterm births associated with Ascending Bacterial Infection (ABI). Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol 77(2): 98-105.

- Berghella V, Rafael TJ, Szychowski JM, Rust OA, Owen J (2011) Cerclage for short cervix on ultrasonography in women with singleton gestations and previous preterm birth: A meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 117(3): 663-671.

- Kindinger LM, MacIntyre DA, Lee YS, Marchesi JR, Smith A, et al. (2017) Relationship between vaginal microbial dysbiosis, inflammation, and pregnancy outcomes in cervical cerclage. Sci Transl Med 8(350): 350ra102.

- Catic A, Foessleitner P, Horvath L, Heinzl F, Mikula F, et al. (2025) The effect of recurrent vaginal infections on preterm birth in a high-risk cohort of women with cervical cerclage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 313: 114634.

© 2025 Alfredo Ovalle S. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)