- Submissions

Full Text

Investigations in Gynecology Research & Womens Health

A Cross-Sectional Analysis to Develop Diagnostic Criteria for the Geriatric Incontinence Syndrome

Candace PA1*, Rebecca N2, Iris L2, Scott RB3, Stephen K4 and George AK5

1 Department of Urology, Section on Female Pelvic Health, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, USA

2 Department of Biostatistics and Data Science, Wake Forest School of Medicine, USA

3 Department of Medicine and Urology, University of California, San Francisco and Division of General Internal Medicine, San Francisco VA Medical Center, USA

4 Sticht Center for Health Aging and Alzheimer’s Prevention, Wake Forest School of Medicine, USA

5 UConn Center on Aging, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, USA

*Corresponding author:Candace PA, Department of Urology, Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

Submission:November 13, 2025;Published: December 02, 2025

ISSN: 2577-2015 Volume5 Issue5

Abstract

Importance: Urinary Incontinence (UI) in older women is heterogeneous. Distinction between pelvic-floor cantered UI and Geriatric Incontinence Syndrome (GIS) is clinically important because GIS is a risk factor for frailty.

Objectives: To generate clinical criteria for the identification of the GIS in the clinical setting.

Study design: We present a cross-sectional analysis of a cohort of 61 community-dwelling women age ≥70 years with moderate-to-severe UI. UI severity is a key clinical feature of GIS. Severe UI is defined as ≥2 UI episodes/day and moderate UI is defined as <2 UI episodes/day. Nine geriatric impairments in physical performance, cognition, activities of daily living, mobility disability, sarcopenia, and frailty were identified based on feasibility of clinical assessment and prior reports of independent associations of each impairment with UI in older adults. Based on the geriatric premise of deficit accumulation, we hypothesized that the concomitant presence of multiple geriatric impairments associated with UI severity would be important criteria for the GIS. Accordingly, an exploratory model was created to test the association between the count of geriatric impairments and UI severity and to explore a ratio threshold for clinical criteria of the GIS.

Result: The count of geriatric impairments was significantly higher among women with severe UI compared to those with moderate UI (mean±SD= 4.4±1.8 vs. 3.4±2.0, p=0.04). Out of 9 geriatric impairments, 62% of participants had 4 or more present.

Conclusion: The deficit accumulation model applied to a 9-item scale of geriatric impairments is associated with GIS severity and may aid in clinical identification.

Keywords:Urinary incontinence; Geriatric syndrome; Older women

Introduction

Urinary Incontinence (UI) in older women is heterogenous and common, negatively impacting up to 60% of US women [1,2]. Some older women have UI the well characterized pelvic floor condition featuring UI symptoms with stress or urgency provocation that is highly responsive to evidenced-based treatment algorithms. However, among older women there is a subset of women with severe mixed UI stress and urgency symptoms that are refractory to standard UI therapies. This phenotype is often present concomitant with geriatric impairments in cognition, mobility, vision, or hearing, thus defining it as a geriatric syndrome [2]. Geriatric syndromes are pre-frail, heterogeneous clinical conditions, defined by their shared risk factors of older age and impairments in physical function, cognition and mobility [3-5]. When present concomitantly, these geriatric impairments have an accumulated impact that increases frailty risk in older adults [6]. Urinary incontinence is a known geriatric syndrome in older adults but is understudied in comparison to other geriatric syndromes of falls and dementia. We have previously characterized the geriatric incontinence syndrome (geriatric UI) as a condition that develops in some older women who have concomitant onset of UI with geriatric impairments in physical function [7]. Detecting the presence of geriatric UI is clinically important because when older women seek care for bothersome UI symptoms, they have higher risk of morbidity and lower treatment efficacy with standard procedure-based UI treatments [8,9]. Thus far, studies have only investigated chronologic age as a predictor for adverse events after UI treatments.

However, it is more plausible that the undetected presence of this geriatric UI phenotype in older women may explain these observations. Our previous work demonstrates that the presence of geriatric impairments in mobility and physical performance and more severe UI symptoms is associated with less change in UI symptoms after non-surgical UI treatments [10]. Cumulatively, these data suggest that greater precision in identifying geriatric UI among older women seeking care for UI treatment is needed to inform evidenced-based treatment algorithms. To meet this goal, reliable mechanisms in identifying geriatric UI in clinical practice is needed. Geriatric syndromes have been clinically defined using different mechanisms to include the deficit accumulation model previously applied to characterize clinical frailty [11]. From our previous work identified UI severity of greater than or equal to 2 UI episodes/day as a significant predictor of poor physical function, slower gait speed, and chair stand pace [12]. Building upon the deficit accumulation model, we hypothesized that it is not the single presence of one geriatric impairment but the culminative impact of multiple geriatric impairments present concomitantly with UI severity, that will be key clinical features of the geriatric incontinence syndrome. In this analysis, we applied a statistical model to test this hypothesis to establish preliminary diagnostic criteria of the geriatric incontinence syndrome.

Materials and Methods

Study design

We report a cross-sectional analysis of a prospective cohort study of community-dwelling women older than 70 years with moderate-to-severe UI symptoms [10]. The inclusion, exclusion and enrolment criteria have been previously reported [10]. Briefly, we included women with a UI diagnosis confirmed by the Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis (QUID) [13] who desired nonsurgical treatment for their UI symptoms and agreed to undergo a 12-week program of structured behavioural therapy to include pelvic floor muscle training. Participants were not currently taking any medication for overactive bladder symptoms and had not had anti-incontinence surgery within 12 months of enrolment.

Measures of urinary incontinence

At baseline, a 3-day bladder diary established daily voiding frequency, UI episodes and type [14]. The mean total UI episodes were determined by the total number of stress and/or urgency UI episodes over a 24-hour period and averaged from the 3-day bladder diary. Using previously established severity criteria [2]; severe UI was defined by ≥2 UI episodes/day and moderate UI defined as <2 UI episodes/day.

Measures of health and impairment

To assess physical function and disability, a combination of objective physical performance tests and self-reported measures used have been previously described [3,4]. The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) was used to determine lower extremity physical function [15,16]. The Pepper Assessment Tool for Disability (PAT-D) measured self-reported changes in disability in activities of daily living, mobility and instrumental activities of daily living. The Mobility Assessment Tool-short form (MAT-sf) assessed functional performance minimizing bias from factors such as age, gender and body image [17,18]. Frailty syndrome is a consequence of geriatric impairments such as urinary incontinence. It is important to note that the presence of geriatric impairments does not indicate the presence of frailty.

Therefore, frailty risk and sarcopenia were determined using

validated questionnaires and physical function measures:

i. Two-questions from the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies

Depression (CES-D) scale to self-report exhaustion and poor

endurance/energy as components of the frailty phenotype

[19];

ii. The “SARC-F” (A questionnaire-based assessment of strength,

assistance with walking, rising from a chair, climbing stairs

and falls) [20]; and

iii. Grip-strength and gait speed to objectively determine presence

of weakness [21]. Cognitive function was assessed using the

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [22].

Defining clinical deficits

Using a previously defined deficit accumulation model of frailty

[23], we hypothesized that the geriatric UI phenotype would be

characterized by the combined presence of multiple evidencedbased

and targeted geriatric impairments and more severe UI

symptoms in older women. The clinical geriatric deficits integrated

in the model were identified based on the following criteria:

i. The presence of statistical significance in associations with UI

incidence and/or severity in a prior study [13]; and

ii. Clinical assessment is relatively feasible to integrate into the

clinical setting. We identified 9 geriatric impairments (Table

1).

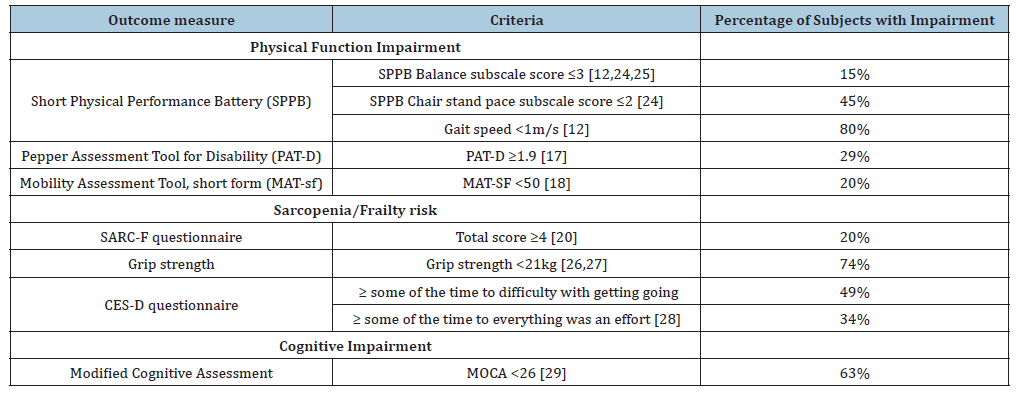

Table 1: Geriatric impairments targeted to characterize the geriatric incontinence syndrome phenotype.

Objective measurements of physical function impairment that have been significantly associated with UI among older women include standing balance, chair stand pace and gait speed [12]. Standing balance is associated with incident UI in previously continent women older than 70 years [7]. A score ≤3 on the SPPB captures persons who cannot do semi-tandem stand and some who cannot do full tandem standing [24]; thus, we used this cut-point [25]. From our original analysis, the mean chair stand pace in this cohort of women was 14.4 seconds which correlates to SPPB subscale cut-point of ≤2 [25]. Older women with severe UI symptoms had a mean gait speed of 0.8 meter/second; thus, we use a gait speed <1.0 meter/second as the deficit marker for gait speed [13].

To assess for disability in mobility and activities of daily living, a MAT-sf score <50 [19] and a PAT-D score ≥1.9 were used as cutoffs [18]. These are standard cut-offs for these validated measures, respectively. We have previously reported on the association of sarcopenia with UI incidence in older women [10]. SARC-F score >4 was used because it is a feasible and reliable clinical tool to screen for sarcopenia [21]. Grip strength is a strong marker of muscle weakness associated with poor physical performance and mobility disability [26]. Weakness is a key element of frailty and sarcopenia [21]. We aimed to identify women with ‘intermediate weakness’ and thus applied a cut-point of <21kg that has been associated with slower gait speed <0.8 meter/second [27]. Answering ‘yes’ to the presence of fatigue or exhaustion was applied as this has been previously associated with UI and frailty [28]. Mild cognitive impairment as defined by the MoCA score of <26 has not been directly associated with UI severity. However, cognitive impairment was included as an important geriatric impairment because it may impact treatment efficacy [29].

Statistical Methods

The deficit accumulation model was developed to define biologic age that accounts for the presence of geriatric impairments separate from chronological age [23]. Using a similar construct, we developed our deficit accumulation model as a simple count of deficits used to create a preliminary diagnostic index defined by the ratio of the total number of deficits present in everyone to the total number of deficits available in the database [30]. For this analysis, we did not use counts of unrelated deficits because of small sample size and exploratory nature of the model. Thus, we included only the 9 geriatric impairments with strong independent associations with UI in older women that were counted and weighted equally because there is not data to suggest otherwise. We then stratified women based on UI severity as this is a clinical feature strongly associated with severity of geriatric physical function impairments. To visually identify any thresholds, a count of geriatric impairments was determined for each individual participant and then summarized by groups based on baseline UI severity.

To describe demographic and clinical characteristics, means and standard deviations represent continuous variables and frequencies and percentages represent categorical variables. Continuous and categorical clinical variables and counts of geriatric deficits of the cohort by UI severity were compared with t-tests and chi-square tests, respectively. The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) area under the curve analysis was examined to determine the cut-point with maximized sensitivity and specificity of agreement with the gold-standard UI severity determined from diary data. The best cut-point was ≥4 deficits compared to <4 deficits. Associations between UI severity and geriatric impairment counts were analysed using categories of ≥4 deficits versus <4. The sensitivity and specificity of a binary cut-point was low; therefore, the frequency of geriatric impairments present was categorized into three groups based on observed breaks in the distribution of the count data: 0-3 deficits, 4-6 deficits, and 7+ deficits. Next, the association between deficit groupings and UI severity was assessed using the chi-square test of general association.

Result

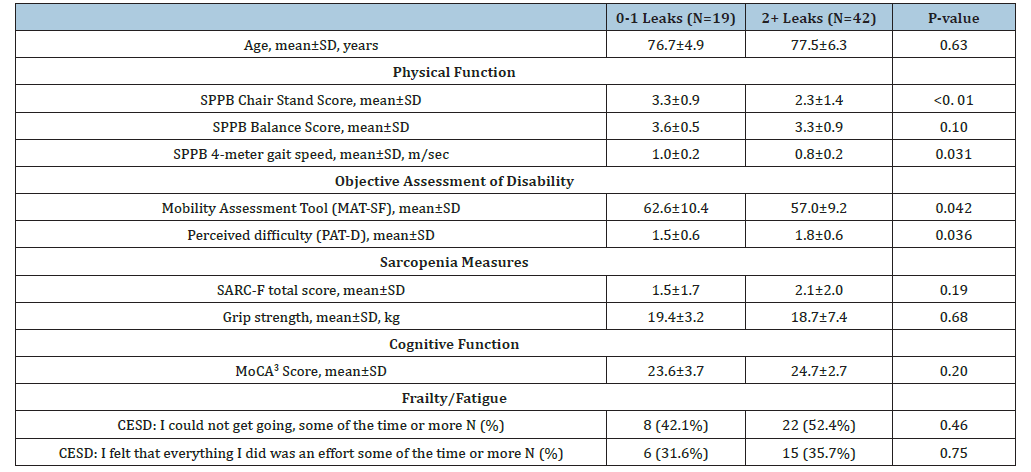

Eighty women completed in-person screening; nine of these were screen fails, yielding 71 enrolled. Ten women did not return their baseline bladder diary and were consequently excluded, leaving 61 women in this analysis. The mean±SD age was 77.3±5.9 years. Women with more severe UI were predominant (69%). Other pertinent demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort have been previously published, but there were no significant differences based on UI severity [12] (Table 2). When we examined the targeted geriatric impairments individually, we observed that chair stand pace and gait speed were significantly slower among women with severe UI compared to women with moderate UI (Table 2). Women with severe UI symptoms also had significantly lower MAT-SF scores indicating greater disability with mobility and significantly higher PAT-D scores that indicated greater disability with activities of daily living (Table 2). There were no significant statistical differences in the presence of mild cognitive impairment, frailty, or sarcopenia risk based on the MoCA, SARC-F, and grip strength respectively between groups based on UI severity (Table 2).

Table 2: Demographic and important clinical characteristics of women with UI based on UI severity.

1 Includes prescription and over the counter medications.

2 Center for epidemiologic studies depression scale -10.

3 Montreal cognitive assessment.

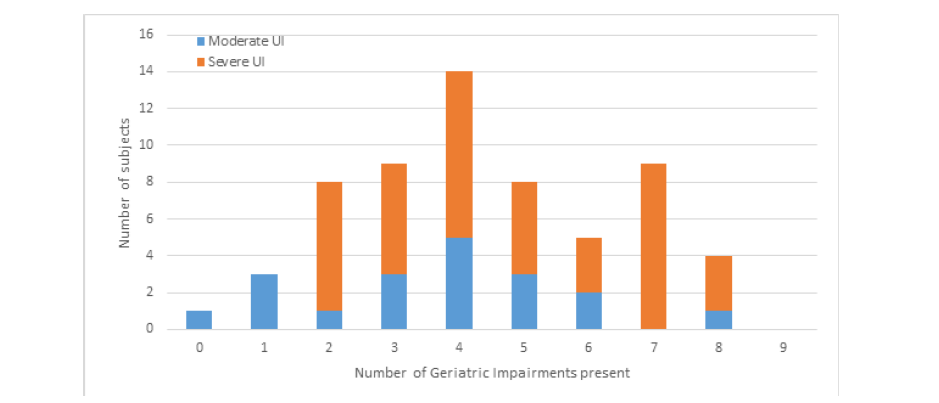

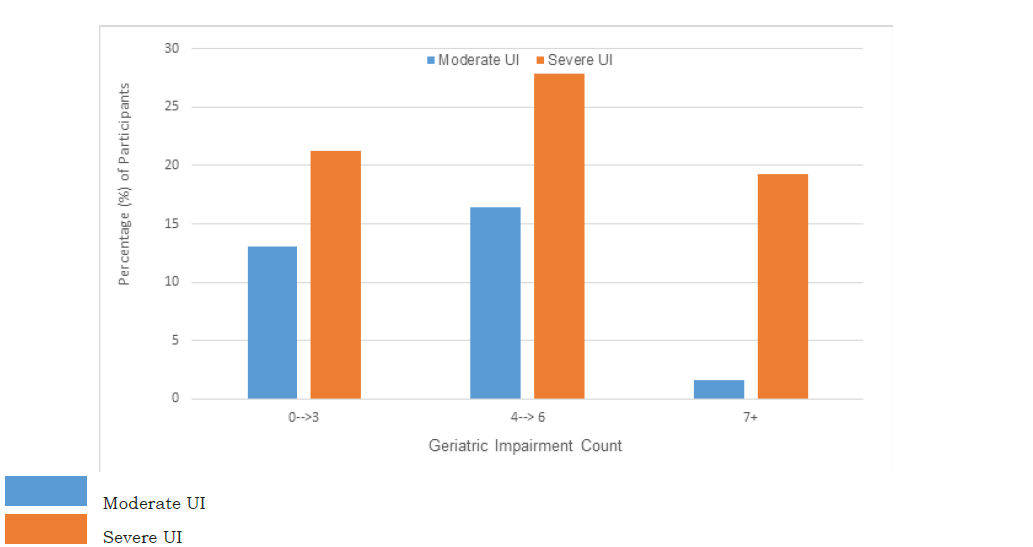

Figure 1A:Distribution of the number of geriatric impairments present among women geriatric UI symptoms based on UI severity:

a. Demonstrates the count of geriatric impairments present based on UI severity as a single category from 0 to 9

b. Demonstrates the categorized counts of the cumulative geriatric impairments based on UI severity.

When examined based on UI severity (moderate UI vs severe UI), the count of cognitive, physical function, and strength related geriatric impairments were significantly higher among women with severe UI symptoms compared to those with moderate UI (p=0.02). The simple count of geriatric impairments present is presented in Figure 1(A); the distribution pattern of geriatric impairment count was similar between groups based on UI severity. However, higher percentages of participants with severe UI had higher counts of geriatric impairments (Figure 1(B)). When categories were made based on the distributions, severe UI symptoms trended towards having greater numbers of geriatric impairments, p=0.11, Figure 1(B). Sixty-two percent of participants were found to have 4 or more geriatric impairments concomitantly. However, the sensitivity of this threshold was regarding predicting UI severity was low, 0.42, 95% CI (0.20, 0.64).

Figure 1B:Represents a test of association between UI severity and count of co-occurring geriatric impairments.

Discussion

In this cohort of women older than 70 years seeking treatment for UI symptoms, incontinence severity of ≥2 UI episodes/day was significantly associated with the co-occurrence of multiple geriatric impairments present in the same individual. This observation confirms our hypothesis that the deficit accumulation model may accurately characterize the nature of the geriatric incontinence syndrome featuring more severe UI symptoms associated with the likely concomitant presence of more than one geriatric impairment. Equipped with this novel observation, geriatric incontinence researchers have a preliminary evidenced based conceptual framework to build upon to further the research into the clinical characteristics and diagnostic criteria for the geriatric incontinence syndrome. Our study is limited in our sample size thus these data require validation in larger population-based studies to establish a clinical definition through testing its ability to discriminate the geriatric incontinence syndrome and its impact on outcomes in clinic practice.

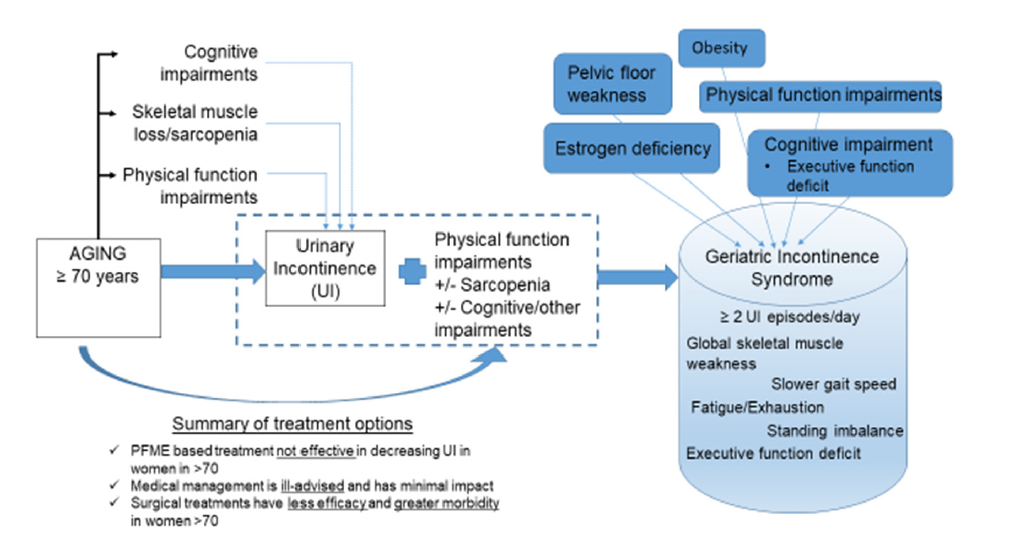

Geriatric syndromes are multi-factorial in aetiology and mechanistically explained by a cumulative effect of shared risk factors for frailty. The presence of a geriatric syndrome is clinically important to detect because when their shared risk factors are present concomitantly worsened clinical outcomes are observed to include increased incidence of frailty, institutionalization, impairments in daily living and death [3,4]. The cumulative deficit model was designed for use in the clinical setting to determine frailty risk. Thus, our hypothesis that this model may be the best mechanism to clinically define the GIS is logical and confirmed by our observation of a close association between UI severity and higher deficit counts in everyone. Further, our proposed conceptual model for the geriatric incontinence syndrome is also supported by our findings (Figure 2). Within this framework, the cumulative impact of multiple geriatric impairments present in an older woman with severe UI symptoms may preliminarily identify the presence of the GIC phenotype (Figure 2). Conceptual framework proposing the mechanism of the geriatric incontinence syndrome phenotype based on cumulative geriatric impairments. Among older women, UI increases in prevalence. Aging is independently associated with impairments in physical function, cognition, and skeletal muscle weakness; these impairments are also associated with UI in older women [12]. The concomitant presence of UI with one or more of these geriatric impairments in older women may characterize GIS [2]. Our current treatment options are not effective and have increased morbidity for older women with UI and concomitant geriatric impairments. GIS is impacted by the concomitant presence of multiple geriatric and gender specific traits. The clinical traits of GIS have been isolated to inform its clinical definition.

Figure 2:Conceptual framework proposing the mechanism of the geriatric incontinence syndrome phenotype based on cumulative geriatric impairments.

It is plausible that the cumulative impact of geriatric impairments in older women with severe UI may impact on safety and success of UI treatments [19]. Prior studies have demonstrated that women older than 65 years are at increased risk for urologic and non-urologic complications after procedure-based UI interventions, suggesting that chronologic age, not biologic age may be a significant risk factor for procedure-related complications [31,32]. The undetected presence of the GIS may account for the refractory nature and poor outcomes that occur in a subset of older women with UI. For example, we examined the effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training and behavioural therapy in this cohort and found that after 12 weeks, there was minimal improvement in their UI symptoms and patient satisfaction with this therapy was low [10]. Additionally, the “anti-aging gene” sirtuin 1, may impact treatment success in older women. Supplementation of sirtuin 1 activators may improve sarcopenia, frailty and kidney function in these women [33,34]. It is plausible that this GIS phenotype will require more precise therapies targeting geriatric impairments as well as pelvic floor dysfunctions for successful treatment. The findings of this study advance our ability to identify women with GIS in clinical practice; a necessary step towards improving the clinical care of all older women with UI.

Our findings are novel and clinically important. Unlike the primary analysis for this cohort, this analysis tests the hypothesis that the deficit accumulation model may be applied to explore diagnostic criteria for the GIS. These data are strengthened by the prospective collection of robust assessments of UI, physical performance, and cognitive geriatric assessments using validated measures and all in each individual participant. Our observations are weakened by the lack of follow-up analyses applying this theory to the cohort to determine its impact on UI symptom reduction with treatment. Further, the cross-sectional analysis limits determination of the causation and consequences of having these cumulative impairments. Results of this first report need to be replicated in other larger cohorts, including some pre- and post-intervention. We also acknowledge that there may be other geriatric deficits that may be important to characterize the phenotype of geriatric urinary incontinence that were not assessed in this study.

Conclusion

The clinical care of older women with urinary incontinence symptoms does not routinely consider the presence of geriatric impairments. Further, the notion of the importance of the geriatric incontinence syndrome is often overlooked. Despite urinary incontinence being an established geriatric syndrome with clear impact on morbidity after urinary incontinence treatments, its value in clinical practice is limited due geriatric UI being poorly characterized and without diagnostic criteria. To date, older women with UI undergo procedure-based treatments with higher risk of refractory UI symptoms and complications. We propose that the presence of a unique UI phenotype, known as the geriatric incontinence syndrome, is distinct from the pelvic floor-based condition of UI in women but is clinically poorly characterized. This study builds upon previously published work to show that GIS may feature more severe UI symptoms present concomitantly with multiple and diverse geriatric impairments. Confirmative data is needed to validate these clinical features and to understand its impact on treatment success for urinary incontinence in older women.

References

- Patel UJ, Amy LG, Heidi WB, Giles DL (2022) Updated prevalence of urinary incontinence in women: 2015-2018 national population-based survey data. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 28(4): 181-187.

- Candace PA, Kuchel GA (2021) Urinary incontinence in older women: A syndrome-based approach to addressing late life heterogeneity. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 48(3): 665-675.

- Sharon KI, Stephanie S, Mary ET, George AC (2007) Geriatric syndromes: Clinical, research and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc 55(5): 780-791.

- Vaughan CP, Markland AD, Phillip PS, Burgio KL, George AK (2018) Report and research agenda of the American geriatric’s society and national institute on aging bedside-to-bench conference on urinary incontinence in older adults: A translational research agenda for a complex geriatric syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc 66(4): 773-782.

- Inouye SK, Mayur DM, Gail V, Williams CS, Scinto JD, et al. (2003) Burden of illness score for elderly persons: Risk adjustment incorporating the cumulative impact of diseases, physiologic abnormalities and functional impairments. Med Care 41(1): 70-83.

- Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, Doucette JT (1995) Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence and functional dependence. Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA 273(17): 1348-1353.

- Candace PA, Julia R, Holly ER, Subak L, Kanaya AM, et al. (2017) Characterizing the functional decline of older women with incident urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 130(5): 1025-1032.

- Richter HE, Patricia SG, Linda B, Anne MS, Peggy AN, et al. (2008) Two-year outcomes after surgery for stress urinary incontinence in older compared with younger women. Obstet Gynecol 112(3): 621-629.

- Cinda LA, Yuko MK, Thomas GW, Emily FH, Dennis W, et al. (2018) Two-Year outcomes of sacral neuromodulation versus onabotulinumtoxin for refractory urgency urinary incontinence: A randomized trial. Eur Urol 74(1): 66-73.

- Candace PA, Leng XI, Matthews CA, Stephen BK, George K, et al. (2022) Examining the role of nonsurgical therapy in the treatment of geriatric urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol 140(2): 243-251.

- Mitnitski A, Rockwood K, Yashin JS (2015) Aging as a process of deficit accumulation, in aging and health-A systems biology perspective.

- Candace PA, Neiberg RH, Leng I, Lisa C, Kuchel GA, et al. (2021) The geriatric incontinence syndrome: Characterizing geriatric incontinence in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc 69(11): 3225-3231.

- Bradley CS, David DR, Ingrid EN, Barber MD, Spino C, et al. (2010) The Questionnaire for Urinary Incontinence Diagnosis (QUID): Validity and responsiveness to change in women undergoing non-surgical therapies for treatment of stress predominant urinary incontinence. Neurourol Urodyn 29(5): 727-734.

- Madill SJ, Stéphanie PD, Tang A, Dumoulin C (2013) Effects of PFM rehabilitation on PFM function and morphology in older women. Neurourol Urodyn 32(8): 1086-1095.

- Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Wallace RB (1995) Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med 332(9): 556-561.

- Pahor M, Blair SN, Mark E, Roger F, Thomas MG, et al. (2006) Effects of a physical activity intervention on measures of physical performance: Results of the lifestyle interventions and independence for elders’ pilot (LIFE-P) study. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci 61(11): 1157-1165.

- Rejeski WJ, Edward HI, Marsh AP, Miller ME, Farmer DF (2008) Measuring disability in older adults: The international classification system of functioning, disability and health (ICF) framework. Geriatr Gerontol Int 8(1): 48-54.

- Rejewski WJ, Edward HI, Anthony PM, Ryan TB (2010) Development and validation of a video-animated tool for assessing mobility. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci 65(6): 664-671.

- Fried LP, Hirsch C, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, et al. (2001) Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci 56(3): M146-M156.

- Malmstrom TK, Miller KD, Eleanor MS, Luigi F, John EM et al. (2016) SARC-F: A symptom score to predict persons with sarcopenia at risk for poor functional outcomes. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 7(1): 28-36.

- Studenski SA, Peters KW, Alley DE, Jack MG, Harris TB, et al. (2014) The FNIH sarcopenia project: Rationale, study description, conference recommendations and final estimates. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci 69(5): 547-558.

- Ziad SN, Valérie B, Isabelle C, Phillips NA, Victor W, et al. (2005) The montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(4): 695-699.

- Mitnitski A, Rockwood K (2015) Aging as a process of deficity accumulation: Its utility and origin, in aging and health-A systems biology perspective. Interdiscip Top Gerontol 40: 85-98.

- Candace PA, Leng I, Matthews CA, Thorne N, Stephen K (2021) Characterizing the physical function decline and disabilities present among older adults with fecal incontinence: A secondary analysis of the health, aging and body composition study. Int Urogynecol J 33(10): 2815-2824.

- Guralnik JM, Scherr PA, Wallace RB, Blazer DG, Glynn RJ, et al. (1994) A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: Association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 49(2): M85-M94.

- Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Corti MC, Fried LP, Kasper J, et al. (1997) Departures from linearity in the relationship between measures of muscular strength and physical performance of the lower extremities: The women's health and aging study. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci 52(5): M275-M285.

- Alley DE, Peters KW, Dam TL, Kiel DP, Jack MG, et al. (2014) Grip strength cut points for the identification of clinically relevant weakness. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci 69(5): 559-566.

- Veronese N, Mirko P, Carlos VB, Maggi S, Jacopo D, et al. (2018) Association between urinary incontinence and frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Geriatr Med 9(5): 571-578.

- Chang PL, Juncos JL, Lisa M, Burgio KL, Alayne DM, et al. (2022) Exploratory evaluation of baseline cognition as a predictor of perceived benefit in a study of behavioural therapy for urinary incontinence in Parkinson disease. Neurourol Urodyn 41(3): 841-846.

- Rockwood K, Mitnitski A (2011) Frailty defined by deficit accumulation and geriatric medicine defined by frailty. Clin Geriatr Med 27(1): 17-26.

- Anger JT, Litwin MS, Wang Q, Pashos CL, Rodríguez LV (2007) The effect of age on outcomes of sling surgery for urinary incontinence. J Am Geriatr Soc 55(12): 1927-1931.

- Komesu YM, Sung VW, Andy U, Holly ER, Albo M, et al. (2018) Refractory urgency urinary incontinence treatment in women: Impact of age on outcomes and complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 218(1): 111.e1-111.e9.

- Martins IJ (2016) Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances in Aging Research 5(1): 09-26.

- Martins IJ (2017) Single gene inactivation with implications to diabetes and multiple organ dysfunction Syndrome. Journal of Clinical Epigenetics 3(3): 24.

© 2025 Candace PA. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)