- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

HIV/AIDS in Old Age: A Silent Challenge for Psychology in Brazil

Maurício Amaro Caxias1*, Aurilene Josefa Cartaxo de Arruda Cavalcanti3, Gerson da Silva Ribeiro3, Lucas Mendes da Silva2, Luís Felipe da Silva Ferreira2, Camila Irani de Albuquerque2, Maria Regivane da Silva Rodrigues2 and Deoclecio Oliveira Lima Barbosa3

1Maurício Caxias de Souza, Nurse, Student of the Public Health Nursing Specialization at the Paulista School of Nursing at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Brazil

2Undergraduate student in Psychology, Maurício de Nassau University Center of João Pessoa (PB), Brazil

2Nurse, Master’s degree in Public Health, Independent Researcher, Brazil

*Corresponding author:Maurício Caxias de Souza, Nurse, Student of the Public Health Nursing Specialization at the Paulista School of Nursing at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Brazil

Submission: November 08, 2025; Published: November 17, 2025

ISSN 2578-0093Volume10 Issue 1

Opinion

Brazil is aging and with it, the challenges to public health are transforming. One issue emerging from invisibility is the growing incidence of HIV/AIDS in the elderly population. Far from the spotlight of prevention campaigns, historically focused on young people and adults, sexuality and, consequently, the vulnerability of older people to the virus, have been neglected. This scenario calls for urgent reflection on the intersection between HIV/AIDS, the elderly, Brazil and the crucial role of psychology [1,2].

The Stigma and Invisibility of Sexuality

Brazilian society, to a large extent, still harbors the stereotype that older people are asexual or that their sex life poses no risk. This mistaken premise is one of the pillars of late diagnosis. Many elderly people, after widowhood or divorce, resume their sex lives, often without proper information about prevention. A lack of concern about pregnancy, for example, leads to the discontinuation of condom use, exposing individuals to Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), including HIV [1-3]. The absence of targeted prevention campaigns and the lack of sensitivity among healthcare professionals in questioning the sexual lives of older adults contribute to diagnoses occurring at advanced stages, with AIDS already manifested, resulting in higher morbidity and mortality in this age group, in contrast to the downward trend in other age groups [3].

The Psychosocial Impact: The Double Burden of Prejudice

A diagnosis of HIV/AIDS in old age imposes a double psychological burden. In addition to dealing with a chronic, potentially stigmatizing illness, the elderly person must face social and often familial prejudice associated with the idea of “deviant behavior” or “inappropriate behavior” for their age [2,3].

A. Isolation and Loneliness: The fear of judgment and rejection leads many to conceal their diagnosis, resulting in social isolation, withdrawal from activities and difficulty seeking support. Loneliness, already a risk in old age, is intensified by forced secrecy [4].

B. Compromised Mental Health: Feelings of shame, guilt, anger, fear, depression and hopelessness are common. The illness affects self-image and identity, especially at a stage of life when tranquility was expected [4].

It is in this context that psychology becomes an indispensable tool. Psychological support should:

a) Promoting Acceptance and Grief: To help the elderly

person process the shock of the diagnosis, cope with losses

(real or symbolic) and rebuild a sense of meaning in life [5].

b) Combating Internal Stigma: Working through internalized

guilt and shame, demystifying the idea that illness is a

punishment or a moral failing [5].

c) Strengthen Adherence to Treatment (ART): The

complexity of the treatment and polypharmacy (use of multiple

medications) require psychological support to ensure strict

adherence, which is fundamental for quality of life and viral

suppression [5,6].

d) Encourage Support Networks: Facilitate communication

with family and close friends (when possible) and encourage

participation in support groups, reducing isolation [6].

e) Reaffirming Sexuality and Desire: To help the elderly

understand their sexuality as a natural and continuous aspect

of life, separating the diagnosis from a moral judgment [7].

A Call to Action: Policies and Vocational Training

Brazil, with its robust Unified Health System (SUS), has the structure to face this challenge. However, urgent measures are needed [8]:

A. Inclusive Prevention Campaigns: Messages that reach and

engage with the elderly population, acknowledging their active

sex lives [8].

B. Training of Healthcare Professionals: Training for doctors,

nurses and crucially, psychologists, to be sensitive, supportive

and proactive in offering HIV testing and managing the

psychosocial issues of HIV in older adults [8].

In Brazil, the issue of aging with HIV/AIDS can no longer be silenced. A humanized biopsychosocial approach is needed that recognizes the elderly person in their entirety, guaranteeing not only the right to physical health, but also to emotional well-being and dignity. Psychology has an ethical and professional role to break the silence, promote dialogue and help this population age with quality of life, even in the face of the virus [9].

Psychology and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Aging

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is the cornerstone of HIV treatment and ensures a near-normal life expectancy for the elderly. However, ensuring adherence is a complex challenge, exacerbated by the aging process [10].

Factors that make adherence difficult

a) Polypharmacy and Forgetfulness: Elderly people often

already use medications for other comorbidities (hypertension,

diabetes, etc.). The addition of antiretroviral therapy (ART)

increases the complexity of their routine, raising the risk of

confusion or forgetting doses [11].

b) Perceived Side Effects: Although current regimens are

more tolerable, the perception of side effects may be more

intense in older bodies or generate anxiety [11].

c) Low Self-Efficacy: A feeling of not being able to manage

the illness, especially after a late diagnosis that may have had a

significant physical or emotional impact [11].

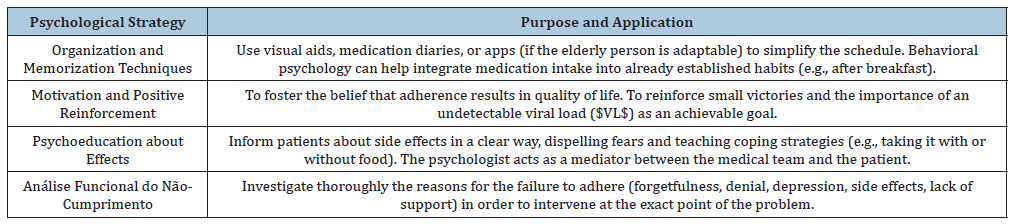

Psychological strategies for adherence [12]:

(Table 1)

Table 1:AM Impeller printing parameters.

Source: The Authors Themselves, 2025.

Support Networks and Breaking Confidentiality: Coping with Isolation

The fear of stigma and serophobia (prejudice against people living with HIV/AIDS) is, in old age, amplified by the fear of disappointing children or being ostracized from the family. The result is self-imposed isolation, which is devastating to mental health [2,3,12].

The role of the psychologist

A. Support for the Disclosure Decision: The psychologist

should not force disclosure, but rather help the elderly person

to weigh the risks and benefits of sharing the diagnosis with

trusted individuals. The focus is on autonomy and well-being

[2,3,12].

B. Social Skills Training: Prepare the elderly person to

deal with negative reactions. This may include simulated

conversations or developing assertive responses to prejudice

[2,3,12].

C. Specific Support Groups: Access to other older adults

living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) is crucial. The group offers

validation, normalizes the experience and reduces the feeling

of being the “only one” in this situation [2,3,12].

D. Family Intervention (if authorized): To help the family

understand that HIV is a chronic and treatable disease,

demystifying contagion and moral stigma. The psychologist can

mediate this difficult communication [2,3,13].

Rebuilding a support network should focus on quality, not quantity. A loyal confidant is more valuable than a large, prejudiced Family [8,12-14].

The Training of Psychology Professionals

To be an agent of change, a psychologist must first deconstruct their own prejudices [2,3,14].

Challenges in training and practice

a) Ageism (Age-based prejudice): The unconscious belief

that sexuality and STIs “are not a problem for older people” can

lead professionals to neglect important questions about risky

behavior or to downplay the emotional impact of the diagnosis

[2,3,14].

b) HIV-phobia and Moralism: Remnants of historical

prejudices linking HIV to “risk groups” or promiscuity can

influence the way people are treated, making it judgmental or

lenient [2,3,14].

c) Lack of Geriatric Knowledge: Lack of familiarity with

the specificities of aging (comorbidities, cognitive decline,

bereavement issues) added to the management of HIV [2,3,14].

Training needs

A. Update on HIV/AIDS: Solid knowledge of the virus’s

biology, advances in ART and the concept of “U=U” (Undetectable

= Untransmutable), to offer accurate information and combat

misinformation [2,3,14].

B. Psych gerontology: A thorough understanding of the

aging process, including life stages, normative crises and issues

of sexuality in old age [5,14].

C. HIV Counseling Techniques: Skills to offer pre- and posttest

counseling, focusing on harm reduction and to manage

acute crises after diagnosis [4,5].

D. Supervision and Self-Care: Spaces for professionals to

reflect on their beliefs, prejudices, and the emotions involved in

working with elderly HIV-positive patients [1,4,5].

Specialized training allows psychologists to work not only in rehabilitation, but also in health promotion and prevention, incorporating the issue of HIV/AIDS into the comprehensive care of the elderly in Brazil [1,4,5].

References

- Caxias MA, Escrig D, Silva LM (2025) Vivences and meanings of psychology students in a spiritist institution for institutionalized elderly in northeast Brazil: An experience report of knowledge in the light of phenomenology. J Psychol Clin Psychiatry 16(5): 231-234.

- Paludo ICP, Olesiak LR, Quintana AM (2021) HIV-positive elderly: The construction of meaning. Psychology Science and Profession 41(e224079): 1-15.

- Altman M (2011) Aging in the light of psychoanalysis. Journal of Psychoanalysis 44(80): 193-206.

- Aragão DRN, Chariglione IPFS (2019) The perception of time through the aging process. Psi UNISC 3(1): 106-120.

- Bacchini AM, Alves LHS, Ceccarelli PR, Moreira ACG (2012) Reflections on the unsettling experience of being HIV/AIDS positive. Psychoanalytic Time 44(2): 271-284.

- Mucida A (2017) The subject does not age: Psychoanalysis and old age. Authentic.

- Queiroz AAFLN, Sousa AFL (2017) PrEP Forum: An online debate on the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in Brazil. Cad Public Health 33(11): e00112516.

- Maurício Caxias de Souza, Aurilene Josefa Cartaxo de Arruda Cavalcanti, Juliana Meira de Vasconcelos Xavier, Daiana Beatriz de Lira e Silva, Pablo Henrique Araujo da Silva, et al. (2023) Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV Among Gay Sex Workers: Nursing in Focus and Elderly Health. Geron & Geriat Stud 8(3): 799-802.

- Souza MC, Lins DR, Saraiva CNR, Almeida SDC (2018) Risk factors related to falls in elderly: A reflective study. MOJ Gerontol Ger 93(4): 131-132.

- Cárdenas CMM (2022) 40 years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic: Reconfigurations of a political-academic agenda. Physis: Collective Health Magazine 32(4): e320400.

- Silva LSR da, Ferreira CH da S, Souza MC de, Cordeiro EL, Pimenta CS, et al. (2019) Care during the pregnancy and postpartum period for women living with HIV/AIDS / Care during the pregnancy and postpartum period for women living with HIV/AIDS. Braz J Hea Rev 2(2): 662-84.

- Pereira DMR, Peçanha LMB, Araújo EC, Sousa AR, Galvão DLS, et al. (2024) Experiences and meanings of trans men about breastfeeding in light of the Theory of Social Representations. Rev Esc Enferm USP 58: e20240006.

- Sousa C, Frazão I, Silva A, Caxias MA (2024) Autonomous management of medication for mental disorders and chronic diseases in primary care: A scoping review protocol. UFPE Nursing Journal online 18: 1-9.

- Caxias MA, Vieira VPA, Silva ARM (2022) Performing kidney transplantation in people living with acquired human immunodeficiency syndrome. International Journal of Development Research 12(5): 56176-56180.

© 2025 Maurício Amaro Caxias. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)