- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

Antipsychotic Risk Mitigation: Informed Consent, Deprescribing and Psychoeducation Talking Points for Lifestyle and Behavior Modification

Cynthia Lewis1, Catherine Jirack Monetti1 and Melissa Scollan-Koliopoulos2*

1Caldwell University, School of Nursing and Health Services, USA

2Dr. Susan L. Davis RN and Richard J. Henley College of Nursing, Sacred Heart University, USA

*Corresponding author:Melissa Scollan-Koliopoulos, Sacred Heart University, USA

Submission: November 13, 2024; Published: November 25, 2024

ISSN 2578-0093Volume9 Issue2

Abstract

Antipsychotics are high risk medications that require informed consent due to their high risk of adverse events, especially in the aging population. Adverse events include ischemic events, falls and a risk of death. A review of interventions to offset antipsychotic risks was conducted searching for major health, medicine and nursing databases. Risks and side effects of antipsychotics were reviewed and ways to mitigate the risks, including education in lifestyle to prevent metabolic derangement. Healthcare providers can contribute to deprescribing efforts when alternatives may be safer by ensuring informed consent during psychoeducation. Once the decision to prescribe an antipsychotic is made, risk mitigation education should begin. Lifestyle interventions and behavior management talking points are evidence-based ways to mitigate risks and promote deprescribing efforts. Talking points can increase self-efficacy to discuss risks and ways to mitigate the risks during psychoeducation. Antipsychotic risk mitigation: Informed consent, deprescribing and psychoeducation talking points for lifestyle and behavior modification.

Keywords:Antipsychotic risks; Deprescribing; Psychoeducation; Ischemia; Metabolic syndrome

Introduction

Antipsychotics are utilized for rapid de-escalation of agitation and aggressive behaviors in older institutionalized adults [1]. Antipsychotic use in the United States is on the rise, with 42.6 million prescription fills as of 2018 by 6.1 million people and an expenditure of $269 a prescription [2]. Patients prescribed antipsychotics require high risk medication monitoring for safety. Healthcare providers play a key role in monitoring for risks and developing psychoeducation interventions to help patients reduce risks. The purpose of this paper is to create an awareness regarding serious risks associated with antipsychotic use and to increase both provider and patient self-efficacy to discuss risks during psychoeducation. Informed consent can be a robust mechanism to facilitate deprescribing efforts, especially when safer alternatives are an option. Healthcare providers may benefit from more information regarding predictors of adverse ischemic events and falls due to metabolic derangement and anticholinergic side effects associated with antipsychotics.

Healthcare provider’s role in psychoeducation in prescribing of antipsychotics

Psychoeducation is an essential healthcare provider care activity and has been reported to improve medication adherence [3] and behavior modification, including increased awareness of how to incorporate healthy lifestyles in older adults [4] and manage behavioral and psychological symptoms in those affected by dementia [5]. When alternatives to antipsychotics are used for rapid de-escalation of agitation or unsafe behaviors, adherence may become a concern. Medication persistence for dementia treatment to manage behavior ranges from 49-75% depending on the environment and circumstances [6]. Alternatives to antipsychotic use require persistence in chronic use for prevention of behavior escalation to prevent resorting to antipsychotics. For example, Citalopram is an effective antidepressant treatment and alternative to antipsychotics for agitation in dementia [7]. Predictors of adherence include positive attitudes toward medication, family involvement and illness insight [8] all impactable by psychoeducation. Generally, sub-optimal adherence to antidepressant therapies can result in reduced effectiveness and this could lead to overuse of antipsychotic prescriptions [9]. Yet, second generation antipsychotics have negligible effect on agitation and typical antipsychotics have only a slight decrease in agitation in older adults [1].

A possible under-recognized essential element of adherence is informed consent and ensuring patients understand the risks versus benefits of antipsychotic use. Informed consent should be re-affirmed during ongoing care interactions and ethical care provisions [10]. Psychoeducation is essential to ensuring informed consent, especially when medications have permanent side effects (i.e. Tardive dyskinesia) or risks of serious adverse events (i.e. Atherosclerotic events leading to heart attack or stroke; or falls). This is especially true when antipsychotics are used without an indication, such as off-label use or in the absence of evidence-based protocols. However, in the United States for example, the Food and Drug Administration does not mandate explicit consent for off-label use because it is often being used for the patient’s best interest [11]. When nurses are unaware of antipsychotic risks, a missed care opportunity to provide psychoeducation exists. Missed care is defined as any aspect of patient care that is omitted or delayed [12]. Nurses play a key role in ensuring that psychoeducation elements of care are not missed to prevent mortality risk [13]. Nurses maintain a critical frontline role in the treatment of patients with behavioral difficulties [14]. Nurses are responsible for providing psychoeducation to patients who are prescribed high risk medications. Some nurses may not feel they have adequate skill to deliver practical education interventions to reduce the risk of injury or complications due to antipsychotic use [15]. Nurses could benefit from interventions they can use to increase their self-efficacy to identify and mitigate risk factors for antipsychotic use injury and morbidity and/or mortality for preventing injury, diabetes, heart disease and stroke. Healthcare providers can also help patients by ensuring they have provided informed consent and are knowledgeable in the risks and can question their prescribers regarding safer alternatives. Providing information needed in a ready to deliver format, talking points can be delivered to patients and families to help consider alternatives overcoming an identified barrier to deprescribing of antipsychotics when appropriate [16]. One study revealed significant knowledge gaps by nurses regarding the risk of appropriate indications for antipsychotic use in elders and the side effects of antipsychotics [17]. Another study revealed beliefs that antipsychotics are beneficial to helping nursing home patient behaviors [18] but do not address risks of ischemic event knowledge. Most research on nursing knowledge of antipsychotics is related to perceptions and beliefs regarding use in managing dementia symptoms [15]. When alternatives to antipsychotic use are not effective or appropriate, psychoeducation of mitigation of the risks is essential.

Psychoeducation to mitigate the risks of appropriate antipsychotic use

Antecedents to the most serious injuries from antipsychotic use include modifiable factors such as metabolic derangement leading to diabetes and dyslipidemia and hypertension that can result in ischemic injury (i.e. cerebrovascular accidents and myocardial infarction) [19]. Other factors leading to serious injury include anticholinergic side effects that can lead to falls from orthostatic hypotension [19]. Other identified risks include less movement when used as a chemical restraint, including pneumonia, kidney injury, thromboembolism, stroke, fracture from falls and myocardial infarction and heart failure [19]. Healthcare providers play a role in educating patients regarding lifestyle behaviors and symptoms self-monitoring when it comes to health prevention education. Yet, few studies reveal healthcare provider, or nurse’s knowledge rates regarding antipsychotic risks. Once antipsychotics have been determined to be medically necessary, many of the risks can be mitigated by ensuring safer lifestyle behaviors. Psychoeducation can include lifestyle behaviors to reduce obesity, prevent diabetes and incorporation of a heart healthy diet, safe physical activity, monitoring of symptoms, falls prevention efforts and sleep hygiene and behavior modification to reduce the need for psychopharmacologic interventions [20]. Patient-centered communication skills training has been shown to improve staff self-efficacy with delivering communication regarding medical care [21]. The philosophical assumptions from Bandura’s theoretical framework include the belief that behavior is influenced by personal factors, environmental factors and cognitive processes and that learning occurs through observation, imitation and rolemodeling [22]. Providing pre-scripted talking points to healthcare providers on what to say to patients is a form of role-modeling. Role-modeling can increase self-efficacy for psychoeducation in clinical practice [3].

Methods

Electronic data bases PubMed, CINAHL, Johanna Briggs Institute, Cochrane Library, OVID Nursing database, Nursing reference Center Plus, PsycINFO, National Library of Medicine and ProQuest were searched to identify the significance of the problem of antipsychotic use risk and the evidence-based interventions to develop psychoeducation to mitigate the risks of antipsychotic use. The scope of the review included appropriate indications, offlabel use and interventions to reduce side effects and/or adverse events that could be translated for psychoeducation at the bedside. Taking points derived from the literature review that can be used in psychoeducation were scripted and presented in tables in this paper.

Results of Literature Review

Antipsychotic prescribing patterns

The number of adults being prescribed an antipsychotic from 2013-2018 increased from 5.0 million to 6.1 million with upwards of 42.6 million prescriptions released [2]. The expenditures of those antipsychotic prescriptions were $11.5 billion dollars in 2018 alone [2]. Within that small percentage is a large amount of unnecessary and inappropriate and/or off label uses without identifiable clinical indications in nursing home residents [23]. On-label clinical indications for the use of antipsychotics include psychosis, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [24], as well as agitation in people with Alzheimer’s dementia using brexpiprazole, a second-generation medication [25]. It is important that the risks do not outweigh the benefits when utilized and that patients provide informed consent. The identified barrier to deprescribing antipsychotics includes low levels of staff education, lack of resources and time, poor medication reviews [15]. Antipsychotics are used off-label to promote sleep and treat agitation in dementia. Oftentimes, antipsychotics are used without clinical indication and may lead to harm [23].

Serious risks associated with antipsychotic use

In the United States Antipsychotics come with a black box warning administered by the food and drug: Administration (FDA) to warn prescribers and patients of the risk of cerebral ischemia and stroke [26]. Both stroke and myocardial infarction have been associated with antipsychotic use [27]. It is unknown how aware prescribers or patients are regarding the risk of adverse cerebral vascular ischemic events. Antipsychotic use is implicated in premature mortality and dangerous adverse events including strokes, motor side effects and anticholinergic side effects that result in falls risk, agitation, confusion, restlessness, cognitive decline and seizures [28]. There is an increased risk of pneumonia, sedation, delirium and urinary retention and weight loss. Additionally, antipsychotics are associated with cardiometabolic risks including hyperglycemia, hypertension, long-QT syndrome, dyslipidemia and increased abdominal girth and weight [28]. The rate of emergency department visits due to life-threatening adverse effects of antipsychotics are as high as 23.7% and 50.8% for non-serious adverse events [29]. One such threatening event attributed to antipsychotic use is ischemic stroke [27]. Exposure (defined as use for 3 days within 30 days of a hospitalization) to an antipsychotic increased the risk of ischemic stroke 1.8 times higher than those not exposed to antipsychotics in a Veteran’s health study [30]. Meta-analyses reveal more than a two-fold increased risk of stroke in those using antipsychotics [27]. The pathophysiologic mechanisms explaining the increased risk of Venous thromboembolism (VTE) among patients receiving antipsychotic medication remains unclear. The factors that may contribute to the occurrence of VTE include the psychotic disorders itself and the exposure to antipsychotic drugs [31]. Immobilization resulting from social withdrawal due to negative symptoms of schizophrenia and major depressive disorders in addition to the sedative side effect of antipsychotic drugs can cause significant venous stasis, a well-known risk factor contributing to VTE [31]. Binding of atypical antipsychotic drugs to a serotonin receptor type 2A with high affinity may increase the platelet aggregation that can play a role in VTE. An increased level of antiphospholipid antibodies found in the patient receiving antipsychotic drugs is an established risk for VTE, however the clinical impact of such high levels is uncertain [31]. Antipsychotics increase cardiometabolic risk and patients need psychoeducation in risk mitigation to prevent diabetes, heart attack and stroke [32]. Meta-analyses show a rapid rise in diabetes, a predictor of stroke and myocardial infarction following the initiation of second-generation antipsychotics [33].

Mitigating risks through evidence-based interventions

The risks of developing diabetes and heart disease are greater in all populations using antipsychotics, but even greater for racial and ethnic minority populations [34]. Identifying risks for diabetes and heart disease by reviewing health history information in the electronic medical record can help identify who to target with tailored psychoeducation on lifestyle factors to mitigate risk once antipsychotics have been determined to be medically necessary to prescribe. Melamed [35], showed that guidelines for metabolic risk screening of individuals taking antipsychotics have been issued, but with little uptake into clinical practice [35]. A moderate effect was seen in risk mitigation when monitoring for body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure, lipids and glucose levels despite barriers to monitoring counselling about Cardiovascular and metabolic health [36]. A systematic review by Ali et al. [36], investigated barriers to monitoring and management of Cardiovascular co-morbidities in patients prescribed antipsychotic medicines which, included barriers to screening, monitoring and management of Cardiovascular and Metabolic side effects [36].

Cezaretto, de barros et al. [37] reported on the comparison of lifestyle psychoeducation and the effects of a traditional lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes prevention and an interdisciplinary approach using psychoeducation [37]. The psychoeducation approach did not have improved outcomes above the traditional approach with improved lipid, glucose indicating that any lifestyle intervention education is helpful for diabetes prevention when educating patients in nutrition and physical activity. Weight gain is associated with antipsychotic nonadherence. Dayabandara et al. [38] conducted a review of the literature and indicated that dietary counseling, exercise programs and cognitive behavioral strategies are equally effective at helping to reduce weight, including adding metformin to the regimen [38]. Weight gain is indicated as being a primary risk factor for increased mortality rates in those using antipsychotics as a predictor of cardiac disease [38]. Weight gain is greatest in the first few weeks of use and patients continue to gain weight for 1-4 years over time [38]. Raza et al. [15] presented a comprehensive literature search and showed implications for practice and education that included barriers to deprescribing antipsychotics due to staff education about dementia and its management, perceived needs of staff for education and training of patients, financial resources and support from other clinical staff [15]. The belief by staff regarding antipsychotics plays an important role in whether to prescribe to patients with dementia [15].

Healthcare providers play an important role in educating patients regarding lifestyle behaviors and symptoms to monitor when it comes to health prevention education. One study revealed significant knowledge gaps in nurses regarding the risk of appropriate indications for antipsychotic use in elders and the side effects of antipsychotics [17]. Most research on nursing knowledge of antipsychotics is related to perceptions and beliefs regarding use in managing dementia symptoms [15]. Staffing ratios can play a role in the use of prescribing antipsychotic medications. If patients are aggressive due to dementia symptoms and nursing homes are short staffed it is easier for prescribers to order an antipsychotic regardless of the risks under the guise of patient safety to keep them calm.

Utilizing talking points derived from evidence-based practice

Evidence-based interventions can help mitigate the risk of antipsychotic-induced cardiometabolic disease risk, including diabetes, heart disease and stroke risk through lifestyle education. The evidence-based psychoeducation interventions are presented in the following (Table 1) patient’s ability to provide informed consent; (2) antipsychotic use risks; (3) monitoring for cardiometabolic risks; (4) lifestyle changes to reduce the cardiometabolic risks; (5) sleep alternatives and (6) coping with problem-behaviors in dementia (Tables 2-7). The evidence-based interventions to mitigate the risk of antipsychotic-induced cardiometabolic disease risk, including diabetes, heart disease, or stroke risk would be to provide lifestyle education as part of mental health visits. There are many programs that have been shown to have effective interventions, such as the National Diabetes Prevention Program [39] and the heart disease and Stroke Prevention Program [40]. A Healthy People 2030 focus is on preventing and treating heart disease and stroke and improving overall cardiovascular health [41]. The existing lifestyle programs could potentially be translated into routine practice for psychoeducation to mitigate the risks associated with antipsychotic use to prevent atherosclerotic and ischemic events. During the informed consent phase of prescribing, weighing the risks and benefits of antipsychotic treatment is particularly important for healthcare providers treating patients with multiple comorbid risk factors for stroke [30]. Psychoeducation can include ensuring informed consent for antipsychotic use and teaching patient’s strategies to self-advocate for cardiometabolic risk screening to prevent cardiovascular disease, stroke and diabetes. Patients should have reinforcement of informed consent principles, including being encouraged to ask their prescriber if safer alternatives are an option especially if the use is for off-label reasons such as sleep [42] or fall prevention [43].

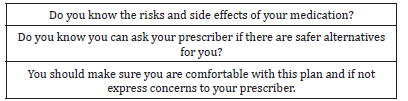

Table 1:Talking points: Patient’s ability to provide informed consent.

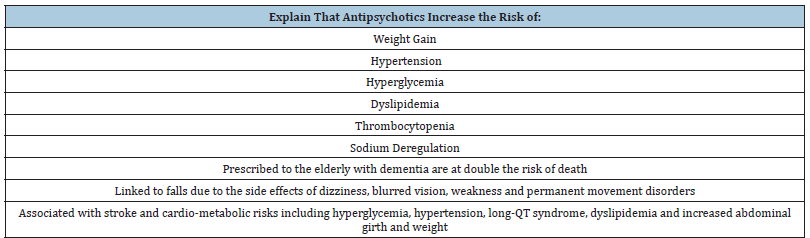

Table 2:Talking points: Antipsychotic use risks.

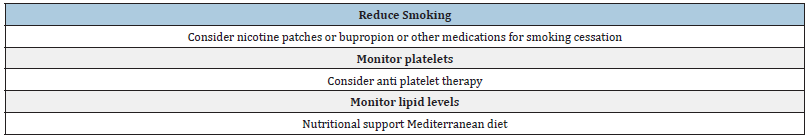

Table 3:Talking points: Monitoring for cardiometabolic risks factors.

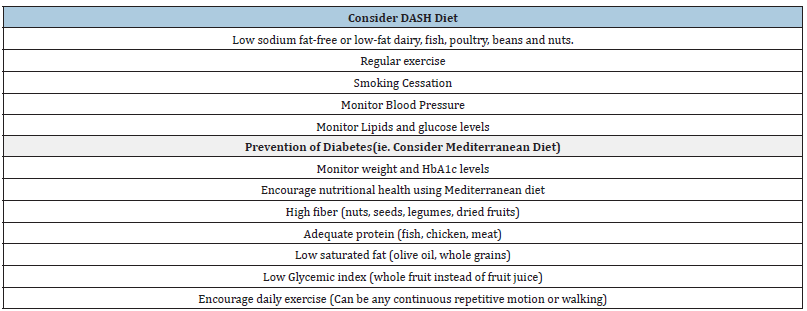

Table 4:Talking points: Lifestyle changes to reduce cardiometabolic risks.

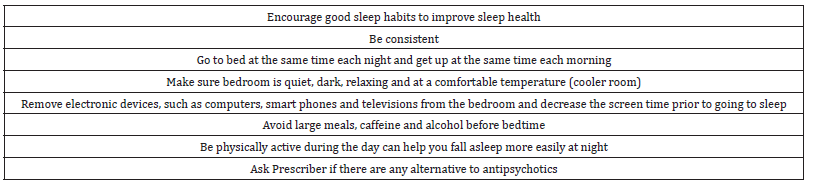

Table 5:Talking points: Sleep alternatives.

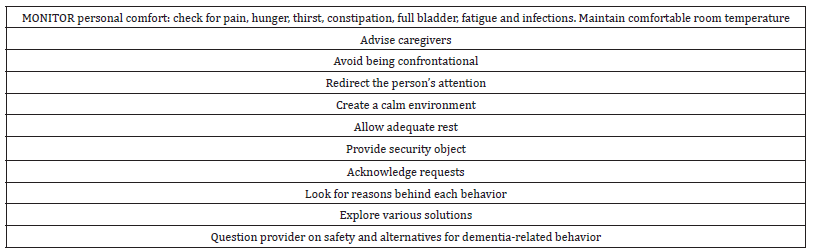

Table 6:Talking Points: Coping with Problem Behaviors in Dementia.

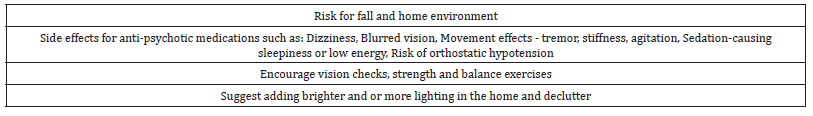

Table 7:Talking points: Falls prevention.

Once prescribed, healthcare providers should assist patients in obtaining cardiometabolic screening and prompt prescribers to order cardiometabolic laboratory tests when indicated. Patients should be educated in the benefits of having their weight, blood pressure, glucose and lipid levels monitored frequently while using antipsychotic medication. Weighing the risks and benefits of antipsychotic treatment is particularly important for providers treating patients with multiple comorbid risk factors for stroke [30]. Evaluating individual risk factors assessment for VTE before commencing antipsychotic drugs should be considered especially, in high-risk situations where adding such agents will increase the risk of VTE. The individuals who are at high risk for VTE and using antipsychotic drugs should be informed and educated about the symptoms of DVT and PE in addition to the importance of seeking immediate medical care [30].

Conclusion

Injury from antipsychotic use can be due to falls or associated with ischemic events and sudden cardiac death or stroke, due in part to metabolic derangement that can be altered with lifestyle changes [19]. In some cases, the best practice maybe to find alternatives, such as when antipsychotics are used off label for sleep or dementia behaviors [44], especially given the paradox that they are sometimes prescribed to improve cognitive function, yet they may cause cognitive decline with long-term use [45]. Providing healthcare providers caring for older adults with scripted talking points to reduce risk from antipsychotic use is a means of ensuring gaps in knowledge do not impede certainty in content deliverables for psychoeducation. It is especially important that all prescribers understand the limitations of evidence and weigh it against the risks when prescribing with off-label use, as is commonly seen with antipsychotic use [46]. Psychoeducation ensuring informed consent is essential in psychoeducation of older individuals and their caregivers [47]. Once the decision has been made to utilize an antipsychotic, mitigation of risks is a priority in psychoeducation provision with lifestyle and self-monitoring education to prevent injury and falls.

References

- Mühlbauer V, Möhler R, Dichter MN, Zuidema SU, Köpke S, et al. (2021) Antipsychotics for agitation and psychosis in people with Alzheimer’s Disease and vascular dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 12(12): CD013304.

- Ahrnsbrak R, Stagnitti MN (2021) Comparison of antidepressant and antipsychotic utilization and expenditures in the US. Civilian Population 2013 and 2016.

- Matsuda M, Kohno A (2021) Development of blended learning system for nurses to learn the basics of psychoeducation for patients with mental disorders. BMC Nursing 20(1): 164.

- Verstaen A, Rau HK, Trittschuh EH (2020) Health aging project-brain: A psychoeducational and motivational group for older veterans. Federal Practitioner 37(7): 309-315.

- Alves GS, Casali ME, Veras AB, Carrilho CG, Costa EB, et al. (2020) A systematic review of home-setting psychoeducation interventions for behavioral changes in dementia: Some lessons for the COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic assistance. Frontiers Psychiatry 11: 577871.

- Muñoz CM, Segarra I, Lopez RFJ, Galera R, Cerda B, et al. (2022). Role of caregivers on medication adherence in polymedicated patients with Alzheimer’s disease or other types of dementia. Frontiers Public Health 10: 987936.

- Chen K, Li H, Yang L, Jiang Y (2023) Comparative effective efficacy and safety of antidepressant therapy for the agitation of dementia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Frontiers Aging Neuroscience 15: 1103039.

- El Abdellati K, De Picker L, Morrens M (2020) Antipsychotic treatment failure: A systematic review of risk factors and interventions for treatment adherence in psychosis. Frontiers in Neuroscience 14: 531763.

- Kim Romano DN, Rascati KL, Richards KM, Ford KC, Wilson JP, et al. (2016) Medication adherence and persistence in patients with severe major depressive disorder with psychotic features: Antidepressant and second-generation antipsychotic therapy versus antidepressant monotherapy. Journal of Managed Care Specialty Pharmacy 22(5): 588-596.

- Barker JM, Faase K (2023) Influence of side effect information on patient willingness to take medication: Consequences for informed consent and medication adherence. Internal Medicine Journal 53(9): 1692-1696.

- Syed SA, Dixson BA, Constantino E, Regan J (2020) The law and practice of off-label prescribing and physician promotion. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry Law Online 49(1): 53-59.

- Gustafsson N, Leino KH, Prga I, Suhonen R, Stolt M, et al. (2020) Missed care from the patient’s perspective-A scoping review. Patient Prefer Adherence 14: 383-400.

- Ball J, Griffiths P (2018) Missed nursing care: A key measure for patient safety. Patient Safety Network Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Ludwin BM, Meeks S (2018) Psychological factors related to nurses’ intentions to initiate an antipsychotic or psychosocial intervention with nursing home residents. Geriatric Nursing 39(5): 584-592.

- Raza A, Piekarz H, Jawad S, Langran T, Donyai P, et al. (2023) A systematic review of quantitative studies exploring staff views on antipsychotic use in residents with dementia in care homes. Int J Clin Pharm 45(5): 1050-1061.

- Jaworska N, Krewulak KD, Schalm E, Niven DJ, Ismail Z, et al. (2023) Facilitators and barriers influencing antipsychotic medication prescribing and deprescribing practices in critically ill adult patients: A qualitative study. Journal General Internal Medicine 38(10): 2262-2271.

- Armstrong EC, Hagen B, Smith C, Snelgrove (2008) An exploratory study of nurses’ knowledge of antipsychotic drug use with older persons. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults 9(4).

- Lemay CA, Mazor KM, Field TS, Donovan J, Kanaan A, et al. (2013) Knowledge of and perceived need for evidence-based education about antipsychotic medications among nursing home leadership and staff. Journal of American Medical Directors Association 14(12): 895-900.

- Mok PLH, Carr MJ, Guthrie B, Morales DR, Sheikh A, et al. (2024) Multiple adverse outcomes associated with antipsychotic use in people with dementia: Population based matched cohort study. British Medical Journal 385: e076268.

- Yao S (2020) Minimizing antipsychotic medication side effects in adults diagnosed with mental illness through psychoeducation: An evidence-based approach. Doctor of Nursing Practice Projects pp: 1-52.

- Axboe M, Christensen KS, Kofoed PE, Ammentorp J (2016) Development and validation of a self-efficacy questionnaire (SE-12) measuring the clinical communication skills of healthcare professionals. BMC Medical Education 16(1): 272.

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thoughts and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Introcaso D (2018) The never-ending misuse of antipsychotics in nursing homes. Health Affairs Forefront.

- Todd CI (2018) 9 Things you should know about taking an antipsychotic. SELF.

- FDA (2023) FDA approves first drug to treat agitation symptoms associated with dementia due to Alzheimer’s Disease. US Food and Drug Administration.

- Meeks TW, Jeste DV, Levi EE (2009) Beyond the black box: What is the role for antipsychotics in dementia? Current Psychiatry 7(6): 50-65.

- Zivkovic S, Koh CH, Kaza N, Jackson CA (2019) Antipsychotic drug use and risk of stroke and myocardial infarction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 19(1):189.

- Chow RTS, Whiting D, Favril L, Ostinelli E, Cipriani A, et al. (2023) An umbrella review of adverse effects associated with antipsychotic medications: The need for complementary study designs. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 5: 105454.

- Jeste DV, Maglionem JE (2013) Atypical antipsychotics for older adults: Are they safe and effective as we once thought? Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research 2(4): 355-358.

- Wang S, Linkletter C, Dore D, Mor V, Buka S, et al. (2012) Age, antipsychotics and the risk of ischemic stroke in the veterans health administration. Stroke 43(1): 28-31.

- Hajjiah A, Maadarani O, Bitar Z, Alfasam K, Hana B, et al. (2023) Antipsychotic drugs may contribute to venous thromboembolism-a case report and review of literature. JRSM Open 14(1): 20542704221132142.

- Kanagasundaram P, Lee J, Prasad F, Costa Dookhan KA, Hamel L, et al. (2021) Pharmacological interventions to treat antipsychotic-induced dyslipidemia in schizophrenia patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12.

- Vancampfort D, Firth J, Schuch FB, Rosenbaum S, Mugisha J, et al. (2017) Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 16(3): 308-315.

- Mangurian C, Keenan W, Newcomer JW, Vittinghoff E, Creasman JM, et al. (2017) Diabetes prevalence among racial-ethnic minority group members with severe mental illness taking antipsychotics: Double Jeopardy? Psychiatry Online 68(8): 843-846.

- Melamed OC, Wong EN, LaChance LR, Kanji S, Taylor VH, et al. (2019) Interventions to improve metabolic risk screening among adult patients taking antipsychotic medication: A systematic review. Psychiatry Online 70(12): 1138-1156.

- Ali RA, Jalal Z, Paudyal V (2020) Barriers to monitoring and a management of cardiovascular and metabolic health of patients prescribed antipsychotic drugs: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry.

- Cezaretto A, de Barros CR, de Almeida PB, Siquiera CA, Monfort PM, et al. (2017) Lifestyle intervention using the psychoeducational approach is associated with greater cardiometabolic benefits and retention of individuals with worse health status. Archives of Endocrinology & Metabolism 61(1): 36-44.

- Dayabandara M, Hanwella R, Ratnatunga S, Seneviratne S, Suraweera C, et al. (2017) Antipsychotic-associated weight gain: Management strategies and impact on treatment adherence. Neuropsychiatric Disease Treatment 13: 2231-2241.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (n.d.). National diabetes Prevention program. Retrieved from

- (2011) National Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention Program. Staff orientation guide. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, pp.1-56.

- Morin AK (2014) Off-label use of atypical antipsychotic agents for treatment of insomnia. Mental Health Clinician 49(2): 65-72.

- (2024) Healthy People 2030. Bringing a Healthier Future for All. Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) US.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (n.d.). Tips for better sleep.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury prevention and Control (2015). Preventing Falls: A guide to implementing effective community-based falls prevention programs.

- Allott K, Chopra S, Rogers J, Dauvermann MR, Clark SR, et al. (2024) Advancing understanding of the mechanism of antipsychotic-associated cognitive impairment to minimize harm: A call to action. Molecular Psychiatry 29(8): 2571-2574.

- Thompson J, Stansfeld JL, Cooper RE, Morant N, Crellin NE, et al. (2020) Experiences of taking neuroleptic medication and impacts on symptoms, sense of self and agency: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative data. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology 55(2): 151-164.

© 2024 Melissa Scollan-Koliopoulos. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)