- Submissions

Full Text

Gerontology & Geriatrics Studies

Risk Factors for Sarcopenia in Older People with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Cohort Study in a Public Outpatient Clinic from the South of Brazil

Lindsey M Nakakogue1*, Marcos AS Cabrera2, Clara S Zanchetta3 and Renan H Obata3

1Professor of Medicine at the Pontifical Catholic University of Parana, master’s in health sciences from the Pontifical Catholic University of Parana, PhD in Public Health from the State University of Londrina, Brazil

2Professor of Medicine at the State University of Londrina, PhD in Medical Sciences from the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil

3Medical students from the Pontifical Catholic University of Parana, Brazil

*Corresponding author:Lindsey M Nakakogue, Professor of Medicine at the Pontifical Catholic University of Parana, master’s in health sciences from the Pontifical Catholic University of Parana, PhD in Public Health from the State University of Londrina, Brazil

Submission: November 11, 2024; Published: November 19 2024

ISSN 2578-0093Volume9 Issue2

Abstract

Objective: Analyze the risk factors for sarcopenia in community patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Methods: Fifty-five patients were followed during the years 2022 and 2023. They were subjected to a sociodemographic questionnaire; nutritional, cognitive and functionality assessment; and the SARC-F+CC at the beginning, at 4 and 8 months.

Result: At the end of 8 months of follow up 15 (27.3%) had probable sarcopenia. The older the age, the greater the risk of sarcopenia, a risk of 1.091 (1.018-1.170, p=0.013). There was an association between the reduction in calf circumference and sarcopenia, a risk of 9.391 (2.973-29.664, p<0.001). Older patients with probable sarcopenia had more falls, a risk of 2.459 (1.190-5.081, p=0.015) and worsened functionality, a risk of 5.136 (2.593-10.175, p=0.015).

Conclusion: Sarcopenia in older people with Alzheimer’s disease should be routinely investigated to prevent negative outcomes such as falls and loss of functionality

Keywords:Sarcopenia; Alzheimer; Cohort study; Risk factors

Introduction

The life expectancy increase has caused a concomitant increase in the incidence of diseases related to aging, including Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and sarcopenia. The World Alzheimer Report estimated that in 2019 more than 55 million people lived with dementia in the world and AD was the main cause [1]. According to the First National Dementia Report, it is believed that there are around 2.7 million older people with AD in Brazil but only 20% of cases are properly diagnosed [2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than 50 million people have sarcopenia and it is expected that this number will increase to more than 200 million in the next 40 years. In Brazil, data from the SABE study found a prevalence of 15.4% in older people in the city of Sao Paulo and the FIBRA study in the city of Rio de Janeiro found a prevalence of 10.8% [3,4]. A study from Japan found a prevalence of sarcopenia in older people with AD of 23%, much higher than the 8% in older people without this pathology [5]. Sarcopenia has been studied as a cause and a consequence of cognitive decline. However, there are few longitudinal studies linking sarcopenia and dementia. A higher prevalence of this pathology has been reported in patients with cognitive decline and AD than in individuals with advanced ages, low Body Mass Index (BMI) and normal cognition [6]. In addition, another study showed that slow walking speed and lower grip strength have been linked to cognitive impairment [7].

A longitudinal carried out in Chicago followed 1175 elderly people since 2005, for an average period of 5.6 years, initially without cognitive impairment. Sarcopenia has been associated with a higher risk of AD and MCI and a faster course of cognitive decline [8]. The basis for the association of sarcopenia and cognitive impairment is unknown. One hypothesis studied is that muscle secretes hormone-like proteins that can reach cognitive regions of the brain through systemic circulation, rather than via the CNS connection, to affect cognition. Myokines, secreted by muscle, contribute to the regulation of hippocampal function. Furthermore, myostatin, a potent myokine that modulates muscle atrophy, when blocked, leads to increased muscle mass and grip strength and improved memory and learning in a transgenic model of AD [9]. Another issue that has been little studied but is frequently observed in practice is that the treatment of AD with cholinesterase inhibitors could cause sarcopenia, because of the gastrointestinal side effects and the loss of appetite. A study carried out in Turkey followed 116 patients during the first 6 months of starting treatment with cholinesterase inhibitors and there was no significant change in nutritional parameters, but patients using rivastigmine patch had a better appetite [10].

Methods

Fifty-five adults over age 60 recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s Disease were followed during the years 2022 and 2023. Older people who started treatment for Alzheimer’s disease with cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine or rivastigmine) in a mild or moderate phase, according to the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) less than 6 months ago, were included. Older people with previous conditions that could predispose themselves to sarcopenia were excluded. They are Diabetes Mellitus with glycated hemoglobin >9%, diagnosis of cancer undergoing treatment (except no melanocytic cancer), Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) using continuous oxygen therapy, diagnosed with HIV, Chronic Renal Failure undergoing dialysis treatment. Furthermore, older people who were unable to perform the tests or respond to the requested questionnaires were excluded, whether due to physical or mental disability. The older adults were subjected to a sociodemographic questionnaire, BMI assessment, cognitive assessment using the MMSE, functionality assessment using the Katz Index and the SARCF+ CC at the beginning, at 4 and 8 months. In addition, they were asked about physical exercise, the occurrences of falls, fractures, hospitalizations and adverse reactions to treatment were noted. Laboratory tests were also collected: Blood count, total cholesterol, fasting blood glucose, glycated hemoglobin, albumin, vitamin B12 and vitamin D levels.

The SARC-F+CC is a questionnaire composed of five questions that assess muscle function and strength, associated with measurement of calf circumference (CC) for indirect assessment of muscle mass. Those older people with suspected sarcopenia according to the SARC-F+CC were subjected to the Manual Grip Strength Test and the Sitting and Rising from a Chair Test [11]. The Manual Grip Strength Test was carried out using a dynamometer (handgrip). According to the protocol, the method was applied with the patient sitting, with feet fully supported on the floor, knees positioned at approximately 90°, elbow flexed forming a 90° angle, with the forearm close to the body. To carry out the measurement, maximum grip strength must be applied for about 3 seconds and rest for at least 15 seconds between one measurement and another. An average of three measurements was used. Notes for reduced Hand Grip Strength <27kg for men or <16kg for women were considered [12]. The Sitting and Rising from a Chair Test was carried out by asking the older person to get up and sit down five times from a 43cm chair without support as quickly as possible, with their arms crossed over their chest. The test is considered altered when performance is more than 15 seconds for five climbs [12].

Individuals who obtained a SARCF+CC score of 11-20 and had the Sitting and Rising from a Chair Test or the Manual Grip Strength Test changed were considered to have probable sarcopenia [12]. The analysis of the association between the independent and dependent variables was carried out using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) models for related repeated measures, with the Poisson test for estimating Relative Risk (RR) and 95% Confidence Interval (95CI). The following parameters were used: independent matrix and robust variance. The analyzes were carried out with the support of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences-SPSS (version 25)

Result

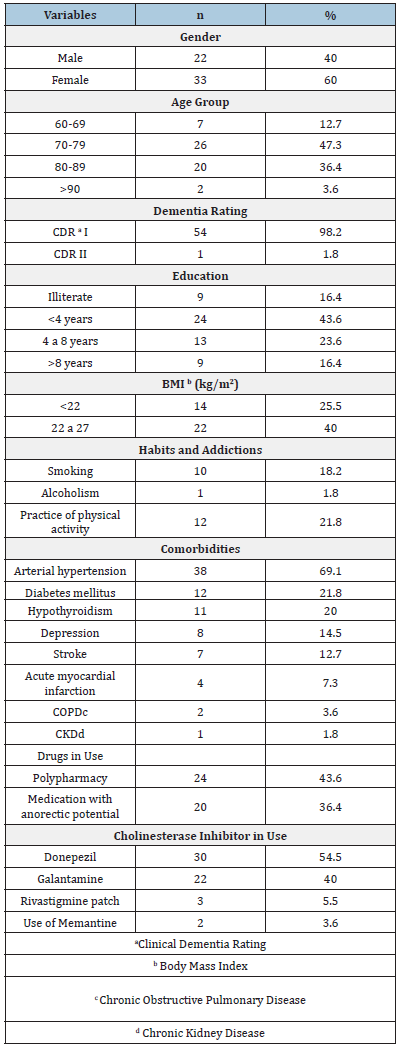

The 55 older patients evaluated, 60% were female, 47.3% were between 70 and 79 years old, 43.6% had less than 4 years of schooling, 98.2% had mild Alzheimer’s (CDR I) and 25.5% had a BMI<22kg/ m2 at the beginning of the assessment. Only 1 older person was institutionalized and 10 lived alone, but with the supervision of their children. Regarding health-related characteristics of the study population, 18.2% were smokers and 21.8% practiced physical activities regularly. The majority had a diagnosis of Arterial Hypertension (69.1%). Almost half used four or more medications regularly (43.6%) and 36.4% used some medication with anorectic potential. Regarding the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease, 54.5% were using donepezil (Table 1). Of the 55 older patients analyzed, 15 (27.3%) had probable sarcopenia according to SARC-F+CC at the end of 8 months of follow-up. The diagnosis of probable sarcopenia was not associated with the type of the cholinesterase inhibitors in use, with the report of side effects related to the treatment, with comorbidities, with polypharmacy, with the use of medications with anorectic potential, with laboratory changes, with the practice of physical activity, nor with a reduction in the MMSE score.

Table 1:Baseline characteristics of the patients.

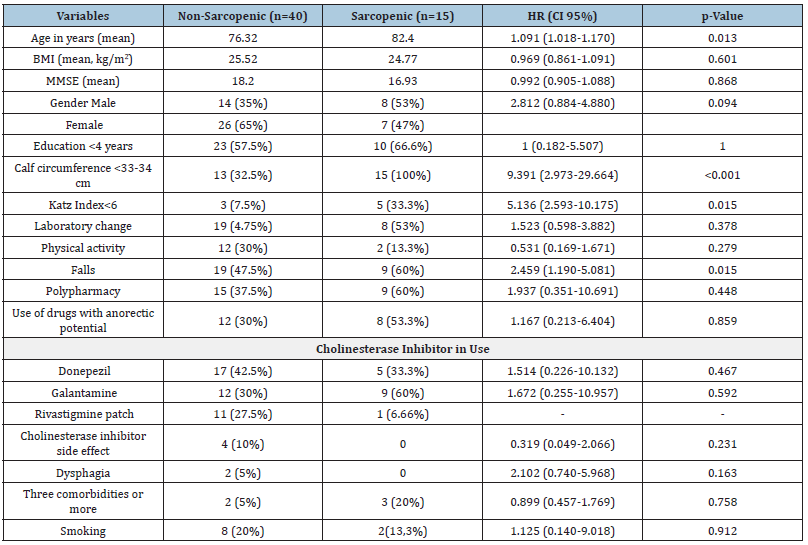

There was no relationship between the diagnosis of sarcopenia and sex, but the older the age, the greater the risk of sarcopenia, a risk of 1.091 (95%CI 1.018-1.170, p=0.013), that is, a 9% increase in risk each year of life. There was an association between the reduction in Calf Circumference and sarcopenia, with a CC< 33- 34cm risk of 9.391 (95%CI 2.973-29.664, p<0.001). Older patients with probable sarcopenia had more falls, a risk of 2.459 (1.190- 5.081) and worsened functionality, a risk of 5.136 (2.593-10.175) compared to older patients without sarcopenia (95% CI, p=0.015) (Table 2).

Table 2:Distribution of the variables in relation to the outcome of sarcopenia in patients with AD after 8 months of follow-up.

Discussion

The type of cholinesterase inhibitor used for the treatment of AD was not associated with sarcopenia. Despite these results, a systematic review revealed that anorexia was the most common psychiatric adverse event reported by patients taking these medicines, with data coming from 27 trials and 720 affected patients out of 10.123 exposed patients [13]. There was a reduction in BMI in the older patients who developed sarcopenia but without statistical significance. Polypharmacy and the use of medications with anorectic potential were also not associated with sarcopenia. A case-control study carried out with 205 older people with mild cognitive impairment and mild AD in Japan demonstrated an association between sarcopenia and BMI and polypharmacy. Perhaps a follow-up period longer than 8 months could also demonstrate this relationship between BMI and sarcopenia in our study [14]. Probable sarcopenia was associated with a greater risk of falls and loss of functionality in this study. A systematic review included four studies, totaling 3263 older people and in three of them there was an association between sarcopenia and falls. In this study it was found that older people with cognitive impairment who suffered falls had a 1.88 times greater risk of having sarcopenia [15].

Calf Circumference (CC) demonstrated a strong association with sarcopenia in this study. This result seems redundant, but it is worth highlighting that the original version of the SARC-F by Malmstrom et al does not require the measurement of calf circumference; it was only in the validation of the SARC-F in Brazil made by Barbosa-Silva et al that CC was associated with the test [16]. In an observational study by Bramato et al [17] the SARC-F was applied to 130 elderly people with Alzheimer’s disease and a sensitivity of 9.7% and a specificity of 82.8% were found, suggesting that the SARC-F is not a good tool to screen for sarcopenia in this population [17]. In 8 months of follow-up, the number of older people with probable sarcopenia increased from 9 to 27%. It was a significant increase in a short period, associated with falls and loss of functionality, without cognitive worsening assessed by the MMSE. This result makes us reflect on whether sarcopenia could be a risk factor for worsening functionality in older patients with dementia, even before cognitive worsening. In a cohort study of 2.288 participants over 65 years of age and initially free of dementia, people with poor physical function had an increased risk of developing dementia and AD and had an increased rate of cognitive decline during the 6 years of follow-up. And handgrip strength has been associated with an increased risk of dementia among people with possible mild cognitive impairment [18].

This study had some limitations. With the intention of minimizing confounding factors, we had many ineligible patients, making the number of people in the study small. Another limitation was the 8-month follow-up period, which may have been insufficient to verify some associations. However, even in this short period of time we were able to see how much sarcopenia affected this population and its negative effects such as loss of functionality and falls.

Conclusion

Sarcopenia in older people with Alzheimer’s disease should be investigated during the follow-up of every older patient, to prevent negative outcomes such as falls and loss of functionality. The measure of the Calf Circumference is easy and must be included as a screening exam of sarcopenia.

References

- Long S, Benoist C, Weidner W (2023) World Alzheimer report 2023: Reducing dementia risk: Never too early, never too late. Alzheimer’s Disease International, pp: 1-96.

- Ferri CP, Bertola L, Ramos AA, Mata FAF (2023) Rena de: National report on dementia in Brazil. Proadi-SUS.

- Alexandre T da S, Duarte YA, Santos JL, Wong R, Lebrão ML, et al. (2014) Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia among elderly in Brazil: Findings from the sabe study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 18(3): 284-290.

- Campos GC, Lourenço RA, Molina MDCB (2021) Mortality, sarcopenic obesity and sarcopenia: Frailty in Brazilian older people study-fibra-rj. Rev Saude Publica 55: 75.

- Sugimoto T, Ono R, Murata S, Saji N, Matsui Y, et al. (2016) Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia in elderly subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease. Current Alzheimer Research 13(6): 718-726.

- Larsson LE, Wang R, Cederholm T, Wiggenraad F, Rydén M, et al. (2023) Association of sarcopenia and its defining components with the degree of cognitive impairment in a memory clinic population. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease: JAD 96(2): 777-788.

- Ogawa Y, Kaneko Y, Sato T, Shimizu S, Kanetaka H, et al. (2018) Sarcopenia and muscle functions at various stages of Alzheimer Disease. Frontiers in Neurology 9: 710.

- Beeri MS, Leugrans SE, Delbono O, Bennett DA, Buchman AS, et al. (2021) Sarcopenia is associated with incident Alzheimer's dementia, mild cognitive impairment and cognitive decline. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 69(7): 1826-1835.

- Jo D, Yoon G, Kim OY, Song J (2022) A new paradigm in sarcopenia: Cognitive impairment caused by imbalanced myokine secretion and vascular dysfunction. Biomed Pharmacother 147: 112636.

- Soysal P, Isik AT (2016) Effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on nutritional status in elderly patients with dementia: A 6-month follow-up study. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging 20(4): 398-403.

- Malmstrom TK, Miller DK, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Morley JE, et al. (2016) SARC-F: A symptom score to predict persons with sarcopenia at risk for poor functional outcomes. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 7(1): 28-36.

- Cruz Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J (2019) Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 48(1): 16-31.

- Bittner N, Funk CSM, Schmidt A, Bermpohl F, Brandl EJ, et al. (2023) Psychiatric adverse events of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Drugs & aging 40(11): 953-964.

- Kimura A, Sugimoto T, Niida S, Toba K, Sakurai T, et al. (2018) Association between appetite and sarcopenia in patients with mild cognitive impairment and early-stage Alzheimer's disease: A case-control study. Front Nutr 5: 128.

- Fhon JRS, Silva ARF, Lima EFC, Santos Neto APD, Henao Castaño ÁM, et al. (2023) Association between sarcopenia, falls and cognitive impairment in older people: A systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20(5): 4156.

- Barbosa Silva TG, Menezes AM, Bielemann RM, Malmstrom TK, Gonzalez MC, et al. (2016) Enhancing SARC-F: Improving sarcopenia screening in the clinical practice. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 17(12): 1136-1141.

- Bramato G, Barone R, Barulli MR, Zecca C, Tortelli R, et al. (2022) Sarcopenia screening in elderly with Alzheimer's disease: Performances of the SARC-F-3 and MSRA-5 questionnaires. BMC Geriatrics 22(1): 761.

- Wang L, Larson EB, Bowen JD, van Belle G (2006) Performance-based physical function and future dementia in older people. Archives of Internal Medicine 166(10): 1115-1120.

© 2024 Lindsey M Nakakogue. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)