- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Effects of a Habitat Restoration Project for Bird Species Associated with Sandy River Beaches in the Pilica Valley

Sławomir Chmielewski* and Karol Sieczak

Institute of Technology and Life Sciences, Falenty, Al. Hrabska 3, 05-090 Raszyn, Poland

*Corresponding author:Sławomir Chmielewski, Institute of Technology and Life Sciences, Falenty, Al. Hrabska 3, 05-090 Raszyn, Poland

Submission: December 12, 2025; Published: January 30, 2026

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume13 Issue 3

Introduction

Riverine sandy beaches and sparsely vegetated sandbars are among the most dynamic and rapidly disappearing habitats in many European lowland rivers. Channel regulation, natural vegetation succession and increasing recreational pressure reduce the availability of open, predator-poor nesting substrate required by beach‑nesting birds, including terns and plovers of high conservation concern [1,2]. In Natura 2000 sites, such habitats are often explicitly linked to the favourable conservation status of qualifying species and therefore become targets of active management [3].

From a practical perspective, local restoration actions are frequently implemented as one‑off interventions focused on exposing bare sand; however, evidence from successful conservation programmes indicates that habitat creation alone is rarely sufficient. Effective outcomes for colonial terns and other beach‑nesting species usually require parallel measures that limit human and vehicle disturbance, reduce access by terrestrial predators, and provide long‑term control of vegetation succession [4-6]. Social attraction techniques (decoys and playback) may additionally accelerate colonisation when nearby source colonies are weak or absent [7,8].

In 2017, at the request of the Mazowiecko‑Świętokrzyskie Ornithological Society (a non‑governmental organisation), the local government of the Mogielnica Commune implemented a project aimed at restoring breeding habitat for birds associated with sandy areas or areas covered by low vegetation. The project received a positive recommendation from the Regional Directorate for Environmental Protection in Warsaw, as it fell within the scope of conservation measures for the Natura 2000 Special Protection Area (SPA) Dolina Pilicy PLB140003.

The aim of this article is to evaluate the effectiveness of this habitat restoration in re‑establishing breeding by the four target/qualifying river‑beach species previously recorded at the sites (Little Tern Sternula albifrons, Common Tern Sterna hirundo, Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula and Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius), and to identify the main factors that limited the persistence of restoration effects over the subsequent five breeding seasons. By combining a before-after breeding inventory with information on management, disturbance and costs, the study provides practical guidance for future Natura 2000 actions on lowland rivers and contributes to the broader discussion on cost‑effectiveness of riverine habitat restoration for beach‑nesting birds.

Study Area

Two sites in the Pilica River valley (Central Poland) were selected for the restoration of breeding habitats for bird species associated with sandy river beaches.

The first site comprised a 5.2ha fragment of land near the village of Tomczyce (51.627604N, 20.699740E). The area was dominated by riparian willow scrub of the association Salicetum triandro-viminalis and by grassland and tall-herb communities. Along the riverbank, patches of the Oenantho aquaticae- Rorippetum amphibiae association occurred locally, together with reed beds Phragmitetum communis and reed canary-grass stands Glycerietum maximae. Among the sandy patches, large areas of sandy grasslands were present.

The second site comprised a 1.9ha fragment of a river bend of the Pilica near the village of Ulaski Gostomskie (51.618178N, 20.667710E). Along the riverbank, a reed bed had developed, and further inland reed canary-grass stands Phalaridetum arundinaceae occurred, together with initial patches of riparian willow scrub Salicetum triandro-viminalis. The remaining part of the area was dominated by hairgrass sandy swards of the association Spergulo- Corynephoretum.

As part of the restoration of habitats for bird species occurring in the Pilica valley, the following works were carried out in autumn 2017, outside the breeding season: removal of shrubs and trees, levelling of the ground, removal of turf, and importing and spreading of sand.

Methods

In 2017, bird censuses were carried out at both sites using a combined territory-mapping approach (Tomiałojć 1980). Given the small size of the plots, particular emphasis was placed on nest searching. Counts were conducted between approximately 05:00 and 08:00 hours. At each site, six survey visits were made on the following dates: 6 May, 12 May, 20 May, 26 May, 16 June and 23 June.

After implementation of the restoration works, bird censuses were continued for five consecutive breeding seasons. In these later years, the study period was extended because an earlier arrival at the breeding grounds was expected for the target species for which the project was designed. In 2018, eight visits were made (24 April, 8 May, 20 May, 26 May, 9 June, 25 June, 7 July, 22 July); in 2019, ten visits (24 March, 4 April, 14 April, 27 April, 12 May, 30 May, 2 June, 22 June, 16 July, 21 July); in 2020, ten visits (20 April, 4 May, 13 May, 17 May, 2 June, 7 June, 23 June, 28 June, 6 July, 23 July); in 2021, nine visits (14 March, 10 April, 2 May, 12 May, 13 May, 1 June, 3 June, 27 June, 13 July); and in 2022, nine visits (6 March, 10 April, 28 April, 12 May, 14 May, 12 June, 27 June, 9 July, 1 August).

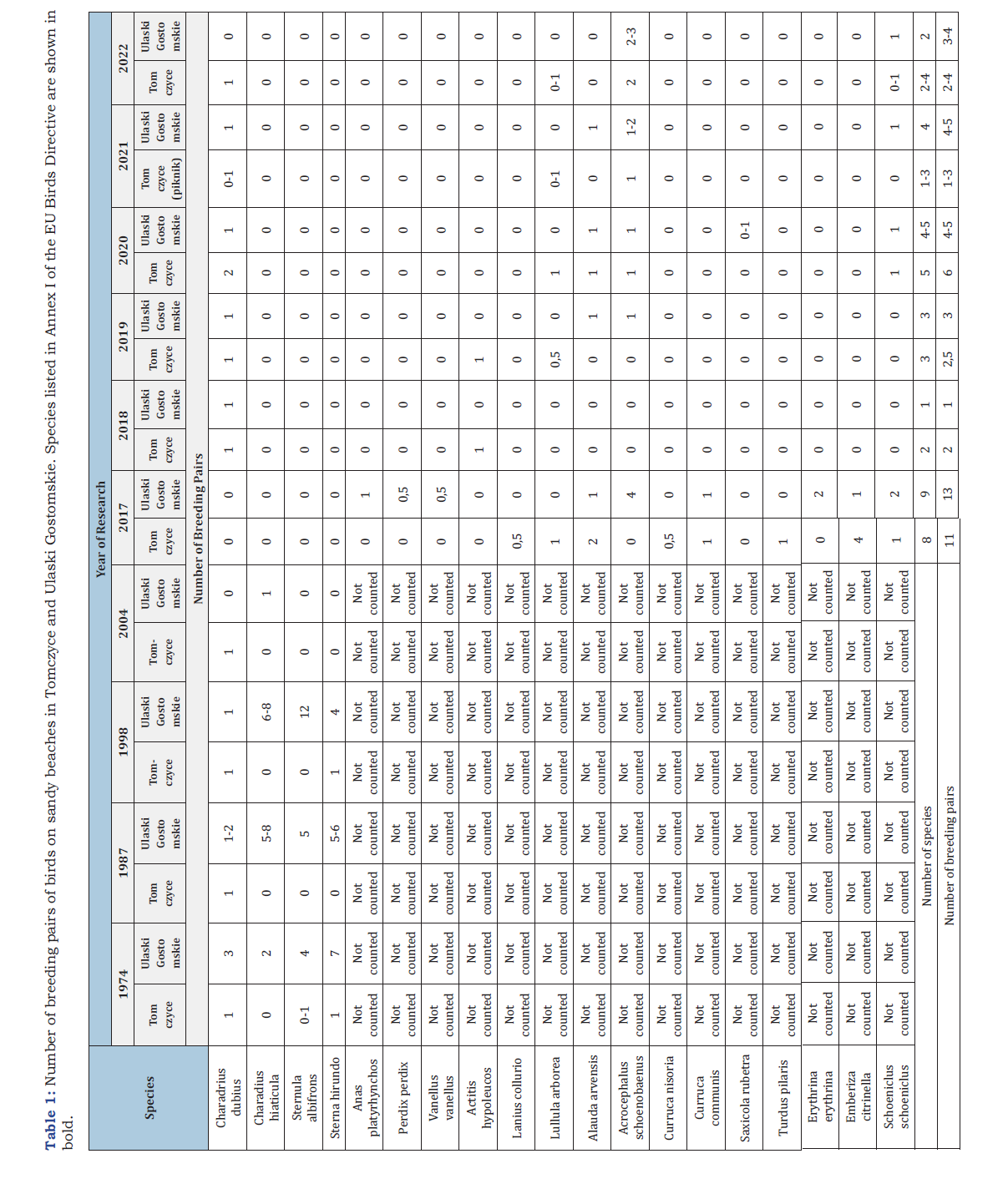

In the years 1974, 1987, 1998 and 2004, the following bird species bred on the described river beaches: Little Tern Sternula albifrons, Common Tern Sterna hirundo (both listed in Annex I of the EU Birds Directive; Directive 2009/147/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the conservation of wild birds), as well as Ringed Plover Charadrius hiaticula and Little Ringed Plover Charadrius dubius (Table 1). All four species were qualifying species for the Natura 2000 SPA Dolina Pilicy PLB140003. In addition, Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos was also a qualifying species in this SPA.

In 1974, 1987, 1998 and 2004, the remaining species listed in the table and recorded in the 2017-2022 inventories were not counted. In 2017-2022, all species breeding on the restored beaches in Tomczyce and Ulaski Gostomskie were censused.

The restoration of sandy beaches in Tomczyce and Ulaski Gostomskie was intended to enable the return of these four target species to their former breeding sites and this was the main objective of the project. The conservation status of the above species and their habitats within the SPA Dolina Pilicy PLB140003 had been assessed as unfavourable. Restoration of their habitats was consistent with the conservation measures specified in the site’s management plan (Dz. Urz. Woj. Mazowieckiego, 9 April 2014, item 3720).

Results

In 1974, 1987, 1998 and 2004, the Tomczyce beach supported up to 6-8 breeding pairs of Ringed Plover, one pair of Little Ringed Plover, one pair of Common Tern and probably one pair of Little Tern (maximum numbers of breeding pairs are given). In the same period, the Ulaski Gostomskie beach supported up to three pairs of Little Ringed Plover, 6-8 pairs of Ringed Plover, up to seven pairs of Common Tern and up to twelve pairs of Little Tern (Table 1).

In 2017, the year of restoration works, none of the four target species nested at either Tomczyce or Ulaski Gostomskie. In 2018- 2022, after habitat restoration, between one and two pairs of Little Ringed Plover bred annually on the Tomczyce beach, and a single pair occurred on the Ulaski Gostomskie beach. In 2022, however, Little Ringed Plover did not breed at Ulaski Gostomskie.

The cost of habitat restoration amounted to 72,951€ for the Tomczyce beach and 26,655€ for the Ulaski Gostomskie beach, i.e. a total of 99,606€. Of this amount, 78,749€ constituted a grant from the Provincial Fund for Environmental Protection in Warsaw.

In the reference year, i.e. prior to restoration, eight species with a total of eleven breeding pairs were recorded on the Tomczyce beach, and nine species with a total of thirteen pairs on the Ulaski Gostomskie beach (Table 1). In the first year after restoration, only one to two species colonised the restored beaches. In the following years, the number of breeding species increased to a maximum of five in 2020, and then began to decline.

Table 1:Number of breeding pairs of birds on sandy beaches in Tomczyce and Ulaski Gostomskie. Species listed in Annex I of the EU Birds Directive are shown in bold.

In 2019 and 2020, the sandy beaches at Tomczyce and Ulaski Gostomskie were maintained as sparsely vegetated sandy fallows. The cost of maintenance amounted to 600€ for the Tomczyce beach and 340€ for the Ulaski Gostomskie beach. In subsequent years (2021 and 2022), the Ulaski Gostomskie beach was left without management, which resulted in gradual vegetation succession towards the communities present prior to restoration. In contrast, in 2021 and 2022 the Tomczyce beach was subjected to intense recreational use, including rallies of historic military vehicles and quad races. This type of use slowed vegetation succession on the beach.

Discussion

According to the updated Standard Data Form for the Natura 2000 SPA Dolina Pilicy PLB140003, Little Tern and Common Tern have recently disappeared as breeding species in the area, while the national population share of Common Sandpiper remains significant but is sensitive to recreational pressure and vegetation succession [3].

In the two restored sandy patches along the Pilica (Tomczyce 5.2ha, Ulaski Gostomskie 1.9ha), a one-off, intensive habitat restoration was carried out (shrubs/trees removed, levelling, sand imported and spread), and in 2019-2020 the state of a “bare sandy fallow” was temporarily maintained. The total cost of the works amounted to approximately 99,606€ (≈14,029€/ha), and maintenance in 2019-2020 cost at least 940€. However, during the 2018-2022 period no breeding of Little Tern or Common Tern (Annex I species) was recorded, and among the remaining qualifying species for the SPA the returns were limited and shortlived (sporadic 1-2 pairs of Little Ringed Plover, and only an episodic breeding record of Common Sandpiper; cf. GDOŚ 2024). From 2021 onwards, birds at Tomczyce were subjected to strong disturbance (gatherings of historic military vehicles, quad races), whereas at Ulaski Gostomskie, following cessation of management, vegetation succession progressed. This indicates that the habitat effects were short-term and did not translate into achieving the project objectives for Annex I species.

In the most successful tern projects, restoring or maintaining bare substrate is only one component of a broader packagecrucial complementary measures include isolation of colonies from terrestrial predators (islands, floating platforms), continuous wardening and fencing to limit access by people, dogs and vehicles, and long-term habitat management. In a five-year national programme in the UK (LIFE Little Tern), coordinated fencing, patrolling and habitat management significantly increased productivity-modelling suggested approximately 1,785 additional fledged chicks compared with a no-action scenario, and birds concentrated in better protected colonies [5,9].

In river systems, hydrological isolation of colonies can be critical. For Interior Least Tern Sternula antillarum in the USA, numerous studies have shown higher breeding success on islands than on sandbars connected to the mainland, particularly under water level regimes that limit predator access [6,10].

In the Drava and Danube catchments, where restoration work targeted both hydromorphology (gravel bars/islands) and the management of recreational use, seasonal closures and zoning of restored areas were explicitly highlighted as preconditions for effective conservation of riverine birds [11,12].

In Central Europe, floating platforms and artificial islands for Common Tern have produced tangible conservation benefits in projects on Lake Drużno and in the Venice Lagoon, showing that such structures reduce breeding losses during high water and maintain high breeding success in years when natural habitats fail [13,14]. In Poland, a broad package of measures (construction and reinforcement of islands, management of vegetation succession, and reduction of disturbance) implemented on the Upper Vistula within the LIFE.VISTULA.PL project resulted in an increase of the Common Tern population to around 600 pairs in 2022, breeding in several colonies [15,16].

Why did the project on the Pilica fail to achieve its intended results? One key factor was the lack of isolation-the restored sand patches were not islands. The literature consistently shows the advantage of island colonies for high tern breeding success [17]. The Pilica results are also consistent with the body of evidence on recreational disturbance: off-road vehicles, walkers and dogs on beaches are known to markedly reduce breeding success of waders and terns unless fencing, seasonal closures and active wardening are implemented in parallel [1,2,5,18]. Another factor is rapid vegetation succession on sandbars, which, if left unmanaged, removes the bare microhabitats required for nesting. This problem is widely documented in river systems and points to the need for ongoing removal of willow and other woody regrowth [19-21].

Finally, successful restoration of colonial terns is often accelerated by social attraction measures such as playback of calls and the use of decoys, particularly when no strong source colony exists nearby. This technique has proved effective in many projects, starting from classic work in Maine [7,8,22]. In addition, a shortage of slightly elevated, flood-free micro-sites within the river channel may have discouraged terns from settling on the restored beaches [23].

Overall, the investment of approximately 100,000€ on 7.1ha in the Pilica valley-with no demonstrated increase in breeding of Annex I species (S. albifrons, S. hirundo) within a five-year periodhas not resulted in a measurable population effect for these species at the SPA scale. For the remaining qualifying species (e.g. A. hypoleucos), the effects were local and temporary [3]. To achieve meaningful outcomes, a full suite of measures is therefore required: isolated microhabitats (islands), reduction of disturbance, annual control of vegetation succession on at least a proportion of the restored area (otherwise effects fade after one-two seasons), andoptionally- social attraction, particularly in the absence of a nearby source colony [4,6,7].

Conclusion

In line with the stated aim of assessing whether a one‑off exposure of bare sand can restore breeding by river‑beach birds, the five‑year post‑restoration monitoring in the Pilica valley shows that the intervention produced only limited and short‑lived biological responses.

(1) None of the two Annex I target species (Little Tern and Common Tern) recolonised the restored sites in 2018-2022, despite substantial financial input (~99,606€ for 7.1ha). (2) Among the remaining qualifying/target species, only Little Ringed Plover returned regularly but at very low numbers (1-2 pairs), while Ringed Plover did not re‑establish breeding. (3) The habitat effect faded quickly because key limiting factors were not addressed: rapid vegetation succession when management stopped (Ulaski Gostomskie) and strong recreational disturbance by vehicles and mass events (Tomczyce).

Therefore, exposing bare sand alone was insufficient to achieve the project objectives at the site scale and did not translate into a measurable improvement for Annex I species within the SPA. Future actions on the Pilica and comparable lowland rivers should combine habitat creation with an integrated management package: (i) creation or maintenance of isolated nesting micro‑habitats (preferably islands or otherwise predator‑limited sites), (ii) legally enforced seasonal restrictions and on‑site measures that prevent access of people, dogs and vehicles (fencing, zoning, wardening), (iii) annual control of woody regrowth on at least part of the restored area, and (iv) where appropriate, social attraction (decoys/playback) to stimulate colonisation. Such a design would better match the evidence base and improve the likelihood that investments result in durable conservation outcomes.

References

- Schlacher TA, Schoeman DS, Dugan JE (2013) Human recreation alters behaviour profiles of non-specialist species on ocean-exposed sandy beaches. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science 118: 1-11.

- Schlacher TA, Weston MA, Maslo B, Dugan JE, Emery KA, et al. (2025) Vehicles kill birds on sandy beaches: The global evidence. Science of the Total Environment 975: 179258.

- GDOŚ (2024) Natura 2000-standard data form: PLB140003 dolina pilicy. General Directorate for Environmental Protection, Poland.

- Wilson LJ, Rendell‑Read S, Lock L, Drewitt AL, Bolton M (2020) Effectiveness of a five‑year project of intensive, regional-scale, coordinated management for little terns Sternula albifrons across the major UK colonies. Journal for Nature Conservation 53: 125779.

- USFWS (2022) Effects of off‑road vehicles on beaches. US Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington DC, USA.

- Catlin DH, Gibson D, Friedrich MJ, Hunt KL, Karpanty SM, et al. (2019) Habitat selection and potential fitness consequences of two early-successional species with differing life-history strategies. Ecology and Evolution 9(24): 13966-13978.

- Kress SW (1983) The use of decoys, sound recordings, and gull control for re-establishing a tern colony in Maine. Colonial Waterbirds 6: 185-196.

- Spatz DR, Kress SW, VanderWerf EA, Guzmánet YB, Taylor G, et al. (2023) Restoration: Social attraction and translocation. Conservation of Marine Birds. Academic Press, Massachusetts, USA.

- DEFRA (2020) Strategy for achieving favourable conservation status for little tern in England, Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, UK.

- USFWS (2019) Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; removal of the interior least tern from the federal List of endangered and threatened wildlife-proposed rule. Federal Register 84(206): 56977-57003.

- NWRM (2018) Riparian ecosystem restoration of the Lower Drava River (LIFE Drava)-case study. Natural Water Retention Measures Platform.

- DRAVA‑LIFE (2024) Layman’s report: Integrated River management-from vision to reality (LIFE14 NAT/HR/000115).

- Coccon F, Borella S, Simeoni N, Malavasi S (2018) Floating rafts as breeding habitats for the common tern Sterna hirundo: Colonization patterns, abundance and reproductive success in the Venice Lagoon. Italian Journal of Ornithology 88(1): 23-32.

- Manikowska-Ślepowrońska B, Ślepowroński K, Jakubas D (2022) The use of artificial floating nest platforms as a conservation measure for the common tern Sterna hirundo: A case study in the RAMSAR site Drużno Lake in northern Poland. The European Zoological Journal 89(1): 229-240.

- VISTULA PL (2023) Protection of waterbird habitats in the upper Vistula River Valley (LIFE16 NAT/PL/000766)-project information and monitoring results.

- NFOŚiGW (2023) LIFE.VISTULA.PL project on the home stretch-press release.

- Federal Register (2021) Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; regulations for interior least tern. Federal Register 86(8): 56977-57003.

- Fuller JL, Osland A, Glick P, Dayer AA (2025) Effectiveness of stewardship and habitat management strategies for coastal birds of the northern Gulf of Mexico. Ornithological Applications 127: 1-21.

- Lamb JS, Kress SW, Hall CS (2011) Managing vegetation to restore tern nesting habitat in the Gulf of Maine. USFWS/CORE Report.

- Smith RK, Pullin AS, Stewart GB, Sutherland WJ (2010) Is predator control an effective strategy for enhancing bird populations? CEE Review 08‑001 (SR38).

- Lott CA, Lott RS, Parnell JF (2013) Interior least tern (Sternula antillarum) breeding distribution and ecology: A review. Waterbirds 36: 1-17.

- Audubon Seabird Institute (2016) Social attraction literature. National Audubon Society, New York, USA.

- Catlin DH, Zeigler SL, Brown MB, Dinan LR, Fraser JJ, et al. (2016) Metapopulation viability of an endangered shorebird depends on dispersal and human-created habitats: piping plovers (Charadrius melodus) and prairie rivers. Movement Ecology 4: 1-15.

© 2026 © Sławomir Chmielewski. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)