- Submissions

Full Text

Environmental Analysis & Ecology Studies

Impact of Land Use/Cover Changes on Physical Water Quality Parameters within the Bamboutos Watershed, Cameroon

Samgwa Innocent1*, Usongo A Patience1, Pamboundam M Charlotte1 and Fombe F Lawrence1,2

1Department of Geography, University of Buea, Cameroon

2Department of Geography and Planning, University of Bamenda, Cameroon

*Corresponding author:Samgwa Innocent, Department of Geography, University of Buea, Cameroon

Submission: October 18, 2024; Published: November 21, 2024

ISSN 2578-0336 Volume12 Issue 4

Abstract

Freshwater quality is highly affected by Land Use/Land Cover Change (LULCC). Streams in the Bamboutos watershed are faced with threats from various land use/cover mutation activities. The objective of the study was to assess the impact of LULCC on physical water parameters from 7 streams flowing through various LULC in the dry and rainy seasons. The Water Quality Index (WQI) was computed from 4 parameters within 7 streams at two sampling points (upstream and downstream). Physical parameters were measured in situ using a portable Compo pH/EC meter and the Analysis of Variance was used to investigate if significant variations in water quality parameters exist. The WHO [1] 2011 standard was then employed to compare values of each element analysed. Results showed significant spatiotemporal variations in stream pH, EC, TDS and water temperatures. Except for TDS with a downstream percentage of (35.71); pH (71.42), EC (57.14) and water temperatures (100) had higher downstream values than those of the upstream. Temporally, dry season values for EC and water temperature were all higher than their corresponding rainy season values, except for pH for all 7 streams. WQI assessment revealed that stream water at all sampling points was good for 5 streams, except for 2 (settlement and mixed land use streams), whose qualities had marginal status. Stream water parameters in this watershed area are thus under threat from land use/cover change activities. The study recommends the re-enforcement of environmental management laws to ensure the supply of good freshwater quality.

Keywords:Water catchment; River Mifi; Land use classification; Stream water quality; Water Quality Index (WQI)

Introduction

The main challenges affecting watersheds at local and regional levels are Land Use/Cover (LULC) changes. These changes have modified the flora, soil and aquatic resources [2]. The result often is the alteration of watershed surfaces and decreased availability of watershed products and services for agriculture, livestock rearing, settlement and other livelihood activities. Land cover land use changes of watersheds have consequences on water quality and increase natural disasters like flooding, mass movement and entire ecosystem processes and functions.

Balgah [3] estimates that about 50% of the earth has been converted by humans for shelter provision, food production, harvesting of raw materials and amusement. Within the twentieth century, about three-quarters of the surface of the earth was mutated by humans [4]. In the global south, tropical deforestation has increased due to the expansion of agrarian land as it is the case in the Brazilian Amazon for soybean, sugar and beef production, Southeast Asian for palm oil production and West Africa especially Nigeria and Cameroon for cocoa farms [5]. As vegetated surfaces are modified, the bearing is seen in the decline of surface water characteristics. In the global North including China, there have rather been forest gain prompted political reformation incentives as it has been the case of China, United States, Canada and Europe. Agricultural lands in these parts of the world have been abandoned for woody vegetal regeneration [5-7].

In countries of the South, spontaneous land use/cover changes have become a serious issue. This is because little attention has been given to land degradation and water pollution. Human activities, population growth, economic development and globalization according to Leemhuisc et al. [8] are responsible for the changes. Although natural processes of floods, landslides, droughts and climate change also contribute to land cover change. According to Abdulai [9] these processes to an extent are induced by anthropogenic activities. In sub-Saharan Africa for instance, about 28% of the inhabitants live in areas that have been degraded by their varied human livelihood functions since 1980 [2,10]. This has triggered urban sprawl and migration into urban areas, with 40% of the African population being urban [11]. This means massive expansion of cultivated land, settlement and infrastructural development, at the expense of natural land cover [1]. Such a situation of urbanization and urban sprawl is quite noticeable at the outskirts of cities of most African countries. In addition to urbanisation, over 60% of the rural population in this region relies on agricultural land for their livelihood. These lands which are common in river basins Khan A et al. [10] have resulted in the alteration of natural land cover and aggressive land use changes that leave adverse consequences on watershed landscapes.

In most of Cameroon cities’ neighbourhood environments, population pressure has transformed forest and afforested lands into agricultural lands. This is the case in Bamenda, Bafoussam, Garoua and Maroua [12]. In the forest region of the Centre, urbanisation, agriculture and changes in agricultural practices have been considered the main causes of LULC changes in the country [12]. The launched of the Five-Year Development plan in the 1970s in Cameroon led to aggressive agricultural practices. This cause agriculture to be seen as the main factor responsible for land degradation, the transformation of forest land into farmlands with increase irrigation practices, and the use of chemicals and fertilizers on the farms in Cameroon [13]. Land use/cover change factors thus include deforestation, agricultural extension and intensification, increasing cattle ranging capacity, settlement expansion and urbanization, and increasing demand for fuel and building materials [2,10,8,12,14,15]. These drivers have greatly contributed to the degradation of surface water in watershed areas, thereby affecting the domestic, agriculture, commercial and industrial needs of this vital liquid. Surface water across the globe is experiencing a declining water quality. About one-third of rivers in the United States and over 45% of rivers in China have been classified as polluted [16]. It is estimated that more than 2 billion people are affected by water shortages in about 40 countries in the world of which one billion lack portable water. More than 40% live in sub-Saharan Africa. The high rate of water contamination in this region is responsible for the death of 1.4 million children annually.

Much of potable water, irrigation water for agriculture, and sources of water for Hydro-Electricity Power (HEP) generation in the world, especially in developing countries according to Munthali et al. [2] come from watershed surface water. Such water sources must be kept safe from activities that degrade the environment. Ironically, surface water is vulnerable to increasing degradation and pollution in the watershed environment. To remedy this situation, the safeguard of surface waters must be done at a larger scale involving the control of activities in the region. This will minimize the degeneration of this resource and the release of pollutants into water sources. The footprint of transformed land canopies is visible in the declining state of its water resources. Kaffoc [17], holds poor governance, the fragmentation of water management institutions, and the absence of water policy aimed at improving water resources responsible for the limping nature of water resource management in Cameroon. Adding to poor governance, progressive increase in freshwater demand, and increased demand for watershed resources, the effect of climate change has also greatly hampered water quality in the country.

The Bamboutos watershed is the second important catchment in Cameroon after the Adamawa Plateaux. This key natural water reservoir supplies at least one third of the water feeding the Hydro Power Station in Edea [18]. It is also a principal source of portable water for the population of the West, Northwest, Southwest and part of the littoral as streams from this watershed are harnessed and distributed to nearby communities and some main cities for their potable water needs. This watershed is unfortunately losing its function as a water catchment. Identifying the threats to stream water characteristics in relation to LULC changes is therefore very relevant. The study therefore assesses the impact of land use/ cover changes on stream water characteristics variability. Water quality assessment is based on the physical variable parameters. Consequently, it improves the understanding of the current status and variability in Surface Water Parameters (SWP) associated with land use changes in the Bamboutos watershed. Such knowledge will help in land use planning as Cameroon envisages Vision 2035, and access to adequate and safe drinking water by increasing the proportion of the population.

Methodology

Study area

Bamboutos watershed is located between latitudes 5˚44’ and 5˚36’ north of the Equator and longitudes 9˚55’ and 10˚07’ east of the Prime Meridian (Map 1) [19]. The Bamboutos watershed is located in the agro-ecological zone of the Western Highlands with a number of natural potentials such as: it water reservoir function, climatic regulator of this region, site of great biological richness with multiple socio-cultural and economic virtues, site with enormous tourism potential and source of food for many Cameroon and Central African cities [20]. Unfortunately, this ecosystem is experiencing intense mutation from anthropogenic activities such as farming and the expansion of built-up areas. The Bamboutos watershed landscape is undulating with diverse landforms ranging from mountain peak, (Mount Bamboutos), valleys, rivers valleys, and steep and gentle slopes. The increasing anthropogenic activities have contributed in altering the natural and cultural land covers in the area. These have created moderately modified sub-region micro-climatic conditions and mild-cold conditions. The cold, cloudy and misty climate is commonly around the upper slopes of mount Bamboutos while the mild cold, clear sky and more sunny climatic characteristics are typical of the lower, gentler dominantly settled slopes of the mountain.

Figure 1:Spatial Layout of the Study Area Source: NIC Database, Realised by Nkemndem Agendia, (2024).

The climate is characterized by dry (November-March) and wet (April-October) seasons. Rainfall is highest between July and September, with August experiencing the highest amount of 430.05mm and the lowest (12.86mm) in January. The mean annual rainfall is 1,918mm and the mean temperature is 18.8 °C [21,22]. Such rainfall characteristics are a result of the instability nature of atmospheric phenomena on the Western Highland and the topographic influence on the moisture of Southwest Monsoon wind. Dry seasons are characterized by dryness and dusty conditions imposed by the Northeast Trade winds that emanate from the Sahara Desert. The mean maximum and minimum temperatures in the Mount Bamboutos Watershed area range from 20 °C to 22 °C and 13 °C to 14 °C respectively. Average temperature varies with seasons, altitudes and concentration of human activities [22]. The minimum temperature occurs in September and the maximum in February. High temperatures are experienced between February and May, with the highest average in February. Generally, rainfall amount shows a decreasing tendency while temperature increases.

Stream water in the dry season is characterized by general shrinkage in the volume of water downstream while some upstream are dry. The drastic shrinking of stream water volume in the dry season could be attributed to disturbances of land cover via different land uses in the watershed which plays down on soil infiltration capacity and underground water recharge [23]. This affects water yield. Climatic variations in the Bamboutos mountain watershed contribute greatly to the mountain forest vegetation type and stream water quantity that once existed in the area. Over time, the natural vegetation has been degraded for livelihood activities due to the increase intensity of various anthropogenic actions that leave footprints on its stream water quality and quantity in the area. River Mifi, which is a main tributary of the Noun River, takes its rise from the Bamboutos Watershed. There are two main tributaries of the Mifi River that rise from this area: the Mifi North and Mifi South. Mifi North rises from Babadjou and part of Santa highlands and the Mifi South tributaries dominantly from Batcham and part of the uplands of Mbouda Sub-Division. The Mifi North and South Rivers that drain the study area constitute the water head of River Mifi which finally discharges in the Noun. The Bamboutos Watershed therefore constitute one of the main watersheds that feed up the Edea Hydro-Electricity power station via the Noun and Sanaga Rivers. This area was once covered by dense equatorial and mountains forest, evident by the present of sacred forests considered as traditional sites with tree characteristics of the equatorial forest in the villages of the Division. With growing population and activities, cattle numbers, the natural forest are increasingly cleared for settlements, and farms and burned by herders for grazing.

Collection of land use/cover imagery data

Land use/cover imagery data collection for this study was done using two platforms: low resolution spot satellite and moderate resolution Landsat imagery systems. This was to analyse land use/ cover change for a period of 30 years (1992 to 2022). Spot satellite provided imagery data for 1992, 2002 and 2012 while Landsat satellite was used to obtain land use/cover data for 2022. The use of 1992 as the base year was because it was the peak of economic crisis in Cameroon that led to the laying off of many State and Para- State workers from their employment units. It was also the peak of the global fall in coffee prices in the world market. These led to many laid-out workers from the civil service and disgruntled coffee farmers to turn to land for their livelihood activities. Spot 4, spot 5 and spot 6 imageries were used because it was difficult to obtain cloud-free images within these periods from renounced sources such as United State Geologic Survey (USGS). Images for 2022 were downloaded from USGS remote sensing platforms as it was favoured by periods of clear cloud over the Bamboutos Mountain area. The images were then imported into a software called ENVI using Meta data. With Meta data, radiometric and geometric corrections were done to reduce irregularities on the satellite images. Pixels were selected for different land use/cover classification which enabled us to have the information.

Considering the understanding of the landscape, Global Positioning System (GPS) data collected on the field were super imposed for accuracy checking and for validation. Land use/cover imageries were then produced with their different statistics. Base maps that could enable us to understand other related aspects such as hydrology were also used. Field data were collected with assistance from some individuals from the community who master the landscape. This brought in the concept of participatory mapping.

The magnitude of land use/cover change, percentage of change and periodic rate of change were calculated by:

Water Quality Sampling and Measurement

Stream water sample sites were selected based on different land use types in the area. Prior to the collection of water samples, a preliminary land use satellite map was used to identify the predominant land uses in the area. A total of 7 land uses were identified. To ascertain the reliability of the number of land uses in the study area as portrayed by the satellite Landsat imageries, a reconnaissance field survey was carried out across the study area in the month of June. Fourteen water samples were therefore collected from the 7 land use sites identified in the area. These were land uses with a stream flowing across. For each land use/cover, stream water samples were collected at two different points along the streams channel, that is, approximated area where each land use/cover begins and ends.

To avoid unpredictable changes in water elements, physical water parameters were measured on-site. Parameters such as pH, Electrical Conductivity (EC), Total Dissolve Solid (TDS) and water temperature were measured in-situ using a portable Compo pH/EC meter. In the measurement of the physical parameters such as water temperature, EC and Total Dissolved Solid in streams with high velocity rate, a five-liter bucket was used to carry flowing stream water from the middle of the channel. After the measurement of each element, the meter was removed from the water for at least 15 seconds before being used in the measurement of the next parameter. The atmospheric temperature was first read, then the water temperature, the EC, pH, and the turbidity. The measurement was done by the researcher with a field assistant aiding in recording the readings. The mean value for the data was determined and their Analysis of Variance calculated. The pH and Electrical Conductivity (EC) meter were calibrated with pH 4.0 and 6.8 buffer solutions and calibration solution respectively. Each sample was collected after pH, EC, and temperature values are stabilized. Distilled water was used to thoroughly rinse instruments immediately after recording the readings at each sample point in order to prevent contamination from the instruments. Physical stream water samples were measured at 14 different streams pints in seven identified land use/cover sites in the study area.

Water Quality Index Assessment

Water Quality Index (WQI) was used to detect and assess the variation of streams water characteristics both upstream and downstream in the study area as shown on Table 1. The calculation of WQI assessment was done following the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) WQI method of 2001. The standard objective values for each parameter were in line with the WHO [1] standard for acceptable parameters concentration.

Table 1:Water Quality Index (WQI), Status and Possible Threats. Horton, (1965)

The CCME calculation consists of three main elements namely, the F1(Scope), F2(Frequency) and, F3(Amplitude) with three major steps of calculation.

Step 1: Calculating the Scope Value (F1 Value):

Step 2: Calculating the Frequency Value (F2 Value)

Step 3: Calculating the Amplitude Value (F3 Value) consisting of three sub sections

Step 3.1: When the test value must not exceed the objective:

Step 3.2: Calculation of the nse value:

Results and Discussion

Impacts of land use/cover dynamics on stream water parameters

The expansion of land use activities such as arable farming, grazing, and residential space, wood harvesting and hunting within the Bamboutos watershed area have changed its surface cover. The effect of these activities and the transformed surfaces are evident in the changing characteristics of stream surface water in the area. This work was focused on the impacts of the various activities carried out within the watershed area on physical water quality parameters. The state of each water parameter had been correlated with land use characteristics in the stream milieu from which water samples were collected.

Table 2:Land use/cover classes characteristics in the Bamboutos watershed. Source: Field work (2022).

The Bamboutos watershed is drained dominantly by the North and South tributaries of River Mifi, with sub-tributaries spreading throughout the area. Streams such as the Laasengue, Tseoumbang, Mogoho and Mougoro take their rise from the Bamboutos Mountain and are confluenced by sub-tributaries as they flow down-stream whereas others such as Touop and Toumougang are sourced from hill slopes at lower altitudes. In sampling stream water in the study area, the dominant land uses through which the streams flow were taken into consideration. The results were correlated with the principal land use characteristic and inferential conclusions made. The physical water properties analysed were water pH, Electrical Conductivity (EC), Total Dissolved Solid (TDS), and temperatures for each of the seven streams. Land use/cover categories in the Bamboutos watershed. The dominant land use/cover categories identified in the Bamboutos watershed were savannah, savannah and eucalyptus, natural forest, gallery forest, wetland, settlement and heterogeneous uses (farmlands, forest and houses) as shown on Table 2.

One of the dominant land use/covers in this area is the tropical grassland, commonly found along an altitude range of 1700m to 2740m. This area is characterised by mountain peaks, medium to very deep slopes, stream sources, eroded steep slope surfaces, eucalyptus and grazing activities. The hilltops are dominated with very short grasses, with heights increasing from hilltops to stream valleys. Stream valleys are narrowed and V-shape as compared to those at downstream which are broad and U-shape. The valleys have natural gallery forests with tall grass species. Of recent, farming activities have expanded into this area, with dominant crops cultivated such as Irish potatoes, carrots, and cabbages. The farms are characterised by irrigation practices with a high application of fertilizers and agro chemicals.

The savannah vegetation advantage of this area has made it the nucleus of grazing activities. Animals grazed are mostly cattle, sheep and goats. Herdsmen move with these animals daily from one hilltop to another in search of pasture and water. In the dry season the scorched vegetation is burned to permit new growth for the animals. During this season, herders shift the grazing of their animals towards the stream valleys where there is fresher pasture. One of the land use/covers identified in the Bamboutos watershed was savannah mixed with eucalyptus. This land use/cover type is common on the steep slope especially in Balatchi. Cattle grazing is not very popular in this area due to poor grassy undergrowth and fenced barbed wire walls. Unfortunately, the fences are often broken by cattle and the vegetation set ablaze by herdsmen, especially in the dry season. This has often resulted in conflicts between farmers and grazers in the area.

The Bamboutos watershed also has natural forested land use/ cover class. These areas are dominated by natural trees. In Babadjou, Batcham and Bangang natural forested areas are common around rural residential areas with a dispersed settlement pattern. Natural forested areas are highly regarded in the Bamboutos watershed area because of their cultural values. Some of the forests are village’s protected sacred forest used for rituals and sacrifices to the deity of the community. Each chiefdom has its traditionally protected area. Families also have pockets of forest or trees that are regarded as family shrines. This explains the dominance of ago-forestry activities around residential areas in the study area. Riverine gallery forest is one of the land use/cover types in the study area. This forest vegetation is dominated by ‘raphia’, natural forest, fruit trees and very tall grasses. River valleys in this watershed are being transformed into intensive commercial farming sites due to their low relief, fertile soil and available water supply all year round.

Wetlands are a common ecosystem in the Bamboutos watershed. These swampy areas are common along broad river valleys. Vegetation in the wetlands is mostly grasses with height variation from stream banks outward. Along stream banks are tall elephant grasses. Unfortunately, the wetlands have been transformed into vegetable farms with high use of chemicals, and fertilizers as is the case in Banshua, Kumbou, and Mbouda areas. Thus, most of the wetlands are now market garden farms. Residential areas were among land use/cover class noted in the study area. These are built up areas with nucleated housing patterns. This urban land use/cover function was observed in part of Babadjou and Mbouda areas. In these areas, house construction has direct bearing on stream water with houses constructed along river valleys. Wastes from home along stream valleys are discarded into stream channels, whereas sediments from areas dug, levelled and compacted residential construction sites end up in stream channels. Heterogeneous surfaces with mixture of farmlands, residences, natural forest and eucalyptus farms were one of the land uses identified in the study area. These land use types were common in Batcham, Bangang and part of Mbouda. The natural forest in this area is under threat from arable farming and settlement expansion.

Physical parameters of stream water in the Bamboutos watershed

Land use activities within a drainage basin play a pivotal role in determining the state of its stream water characteristics. In the Bamboutos watershed, stream water samples collected were analysed to determine their pH, EC, TDS, and temperature, for their physical parameters at upstream and downstream sample sites during the rainy and dry seasons. Water Quality Index was then used to determine the degree of stream water changes for each element tested as shown on Table 3.

Table 3:Spatio-temporal variation of water parameters. Source: Field Work (2022).

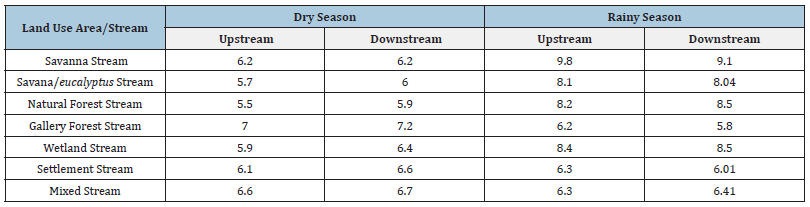

Spatio-temporal variation of pH values within streams under various LULC classes

The average pH values of streams that flow through the 7 land use areas identified in the Bamboutos watershed was higher downstream with a value of 6.95 compared to the upstream value of 6.82, with no significant variation observed. Except for savannah land use stream and gallery forest stream, all the land use streams had mean downstream pH values higher than their corresponding upstream values. Except for savannah land use stream and gallery forest stream, all the land use streams had mean downstream values higher than their corresponding upstream values. This represented 71.4% of land use streams affected by land use practices in the area. The downstream of wetland stream showed a high pH concentration of 7.45, slightly higher than the upstream value of 7.15. This was followed by natural forest stream and savannah/eucalyptus stream, with downstream values of 7.2 and 7.02 respectively with their corresponding upstream values of 6.85 and 6.9. In the dry season, 6 land use streams had downstream pH values higher than upstream values. These were savannah/ eucalyptus, natural forest, gallery forest, wetland, settlement and mixed land use streams. Human activities of arable farming where chemicals and fertilizers are intensely used, the grazing methods of bush burning, continuous trampling of surfaces by herds and digging compaction of surfaces for house construction were the reason behind the have high downstream pH values over those of upstream in these land use streams vicinity.

In the rainy season, only 3 land uses had downstream pH values higher than those of the upstream. These were natural forest streams with a downstream value of 8.50 and upstream value of 8.2; wetland downstream value 8.5 over 8.4 for upstream and 6.41 downstream value for mixed stream against 6.3 for upstream (Table 4). Rainy season pH values ranged from 5.8 to 8, whereas, in the dry season, the range was 5.5 to 7.2. During the wet season, savannah, wetland, natural forest and savannah/eucalyptus land use streams were observed to be slightly alkaline, while gallery forest, statement and mixed land use streams were slightly acidic, with a range of 5.8 to 6.41. In the dry season, the highest pH value was registered by gallery forest, with a neutral pH value of 7 and 7.2 and the lowest by natural forest steam with a value of 5.5. This finding contradicts the results of Maprasit [24] whose work registered higher dry season pH values than those of the rainy season. The high rainy season values observed could be as a result of the diluting effect of runoffs into the stream channels. Efforts should be made towards controlling land use activities in this area. This could help to stabilise pH values to a range that is acceptable for agricultural activities, the survival of plant organisms and for potability.

Table 4:Values of pH at downstream and upstream for both dry and wet seasons in the Bamboutos watershed. Source: Field Work (2022)

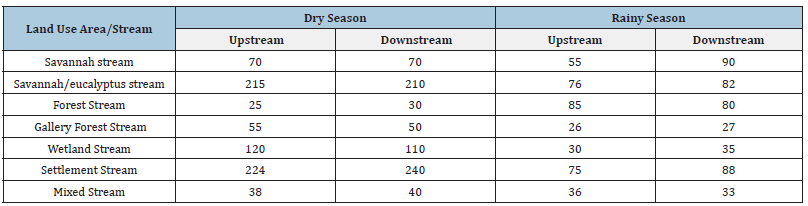

Spatio-temporal variation of Electrical Conductivity (EC) within streams under various LULC classes

Electrical conductivity values of all the streams in the 7 land use areas were observed to vary spatially and with season. Spatially, the mean EC upstream value of (147.14 microsiemens per centimeter (uS/cm)) was observed to be lower than the downstream mean value (169.28μS/cm). The least upstream value was 25μS/cm, recorded at forest land use stream site while 27μS/cm was the lowest downstream value registered at gallery forest land use stream site. Downstream also registered the highest EC value (240μS/cm) compare to that of the upstream (224μS/cm) within the settlement land use stream. During the dry season EC ranged from 25μS/cm to 240μS/cm with a mean EC of 106.929μS/cm while in the rainy season, the EC ranged from 26μS/cm to 90μS/ cm with a mean EC of 87.5μS/cm (Table 5). Five of the 7 land use stream sample sites had higher dry season values than those of the rainy season. These were: savannah/eucalyptus land use stream (424μS/cm against 158μS/cm), gallery forest stream (105μS/cm against 53), wetland land use stream (230μS/cm against 65μS/ cm), settlement land use stream (464μS/cm against 163μS/cm) and mixed land use stream (78μS/cm against 69μS/cm).

Table 5:Values of electrical conductivity at upstream and downstream for both dry and wet seasons in the Bamboutos watershed. Source: Field Work (2022).

The high EC downstream values for both dry and rainy seasons within the forest, wetland and settlement land use streams could be due to intensive farming activities. The farms are cleared, ploughed, irrigated (in the dry season), and weeded in both seasons, a practice that enhanced soil erosion and stream water pollution. Eucalyptus farms have also been converted into arable farms, while grassy surfaces are intensively grazed. To maintain the electrical conductivities of streams within the fresh water range of 0 to 200uS/cm, land use activities that enhance soil surface exposure should be discouraged, especially in the dry season.

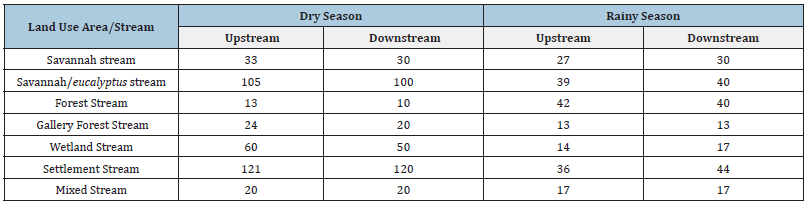

Spatio-temporal variation of Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) within streams under various LULC classes

In the Bamboutos watershed, TDS values upstream varied greatly from those downstream. Upstream values were generally higher than those of downstream, though not significant. The mean upstream TDS value was 40.28Mg/L and that at downstream was 39.5Mg/L. Forest land use stream had the lowest upstream value of 13Mg/L while the least downstream value of 10Mg/L was registered by forest land use stream. The difference between the highest upstream and downstream values also had no significant variation. Settlement land use stream had the highest upstream TDS value of 121Mg/L and only differed by 1Mg/L to downstream value of 120Mg/L registered by settlement land use stream. The work of Usongo & Bryan [25], illustrated related increase in total dissolved solids with distance from the upstream source, which are clear indications of the impact of land use change activities on the pH of stream water in the area. Contamination from agricultural fields and household waste account for the high TDS values of settlement land use streams. Seasonally, a great variation was noted in the concentration of TDS with a mean dry season values of 51.85Mg/L against the rainy season value of 27.78Mg/L. The least dry season value was 10Mg/L (within forest land use stream, against a rainy season value of 13Mg/L; while the highest dry season value of 121Mg/L was observed to have a significant difference from rainy season value of 44g/L (Table 6).

Table 6:State of Total Dissolved Solids in streams of the Bamboutos watershed. Source: Field Work (2022)

The variation between upstream and downstream TDS values could be due to the nature of the dominant activities carried out in the area. The grazing of livestock and cultivation of eucalyptus of Savannah/eucalyptus land use stream sample point area have been invaded by farmers. Farming activities have increased in intensity during the dry and rainy seasons. Places that were not cultivated in the rainy season have been brought under intensive farming activities using irrigation water supply schemes. Lands within this stream area that were not irrigated were cleared and softened in preparation for farming in the rainy season, thereby making the soil more exposed. Also, eucalyptus that were within this stream milieu were cut and sown into planks and the land converted into arable farms, while the remaining grassy surfaces were experiencing intensive concentration of grazing.

Water sample collection point for settlement land use stream located at the downstream was dominated by arable farming activities. The farms were cleared in preparation for tillage in the rainy season. Soil particle were thus blown in to this stream water source whose water volume during this season had reduced to almost the size of a brook. Bikes and dresses are also washed in this stream. Thus, the high concentration of sediments in this very narrow dry season stream channel. There is therefore the need for sustainable land use practice measures to be re-enforced in settlement land use stream sites. These should be land use activities that use lesser chemicals and fertilizers in agricultural fields. Land use practices that compromise the exposure of soil surfaces could help to reduce the quantity of organic and inorganic materials release into stream water sources. Reforestation programs prohibition of agricultural activities on steep slopes on which there is high application of artificial soil nutrients, chemicals and high rate of soil erosion experienced.

Spatio-temporal variation of temperature ranges within streams under various LULC classes

Stream water temperatures in the study area varied spatially upstream and downstream and seasonally as presented on table 4.6. Water temperatures upstream were observed to be lower with a generalized average of 18.08 °C compared to that downstream with an average of 19.52 °C. Savannah land use stream registered the lowest both upstream and downstream with an upstream temperature of 9.2 °C and downstream temperature of 10.3 °C. Highest temperatures were observed to also vary spatially. Wetland land use stream recorded the highest upstream temperature (23.2 °C) while wetland and settlement land uses recorded the highest downstream temperature (24 °C). The variation in upstream and downstream temperatures revealed a significant difference over space. This spatial temperature variation levels could be as a result of the effect of altitude and scanty vegetation shades along the river channels. At the downstream, most of the stream channels were characterised by shades from ‘raphia’ plants, natural trees and tall grasses more than those of the up-stream dominated by grassy vegetation. Water volume and depth also varied downstream and up-stream, with the downstream being joint by tributaries experiencing increased volume and depth (Table 7).

Table 7:Values of stream temperature at upstream and downstream for both rainy and dry seasons in the Bamboutos watershed. Source: Field Work (2022).

Seasonally, the temperature was higher during the dry season compared to the rainy season with averages of 20.31 °C and 17.17 °C respectively. Savannah land use stream registered the lowest temperatures in both seasons (14 °C in the dry season and 9.2 °C in the rainy season), whereas, the highest were recorded in the dry season by wetland land use stream (24 °C) and settlement (24 °C) land use stream and in the rainy season by settlement land use stream (21.5 °C). Savannah land use stream registered the lowest temperature in both seasons because of its altitude advantage (2,440m), while wetland land use stream and settlement land use stream had the highest temperature (1,319m) due to their low altitude location advantage. The influence of land use/cover mutation on stream water parameters could have also contributed to temperature variation in streams of the various land use areas. Despite such a high-water temperature value of streams in this study area, stream temperature values remain far below the WHO 2011 acceptable limit of 30 °C.

In the Bamboutos watershed area, 71% of stream pH values, 100% of stream E.C, and 85.7% of TDSs of the 7 stream water at downstream of each land use area were found to be influenced by the various anthropogenic activities carried out in the area. Areas where streams flow along deforested areas were found to display higher temperature than stream channels areas canopied by tree vegetation. These findings were in conformity with the work of Camera et al [26]; Peng et al. [27]; Banner et al. [28]; Siyue et al. [29]; Strilent & Satika [30] in which physical variables of pH, EC, TDS, and temperatures showed significant variation over space, similar to the spatial variation in the Bamboutos watershed area where downstream values of each land use area were observed to be higher than those upstream. Such increase in downstream physical water properties is an indication of the destruction of vegetation cover for agricultural and residential purposes.

Compliance of water quality measurements with WHO standards for drinking water

The state of the various land use stream pH, electrical conductivity, total dissolved solids and temperature characteristics in the Bamboutos watershed were measured with WHO [1] (2011) standard in order to determine their portability compliance. The mean electrical conductivity, total dissolved solids and temperatures values were all within the WHO, 2011 potable water quality standard spatially and seasonally except for dry season pH values (Table 6 & Figure 1). The average pH of one downstream land use stream (settlement, 6.30) and 2 upstream land use streams (settlement, 6.2; mixed, 6.45) were observed to be below the minimum WHO standard limit of 6.5. Although the mean pH of 6.286 was lower than the acceptable 6.5 to 8.5 level, the downstream values of savannah, savannah/eucalyptus, natural forest, gallery forest, wetland and mixed land use streams had pH values within WHO standard requirement. At the upstream level, savannah, savannah/eucalyptus, natural forest, gallery forest and wetlands land use stream pH readings were also within the acceptable level (Table 8).

Table 8:Statistical summary data of the physico-chemical and biological parameters of samples in compliance with WHO (2011) drinking water standards. Source: Fieldwork, (2022); WHO, (2011)

Figure 2:Bar graphs showing the physical land use stream parameters in compliance with WHO (2011) acceptable limits.

Source: Fieldwork, (2022)

(ST1* Savannah land use stream, ST2* Savannah/eucalyptus land use stream, ST3* Natural forest land use stream,

ST4* Gallery forest land use stream, ST5* Wetland use stream, ST6* Settlement land use stream and ST7* Mixed

land use stream).

Electrical Conductivity (EC), Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) and temperatures values for each land use stream both down and upstream were within WHO (2011) water quality standard. For instance, EC value of 240μS/cm, and 224μS/cm, at both down and upstream, 120mg/L and 121mg/L TDS values for down and upstream readings and 22.75 °C and 21.5 °C down and upstream temperatures registered were all within WHO 2011 permissible level.

Seasonally, land use streams pH, EC, TDS and temperatures showed compliance with WHO (2011) standard, except for the mean dry season pH value of (6.286). The mean dry season EC value of 106.929μS/cm, TDS Value of 51.851mg/L and temperature value of 20.314 °C were within the standard set by WHO (2011) as indicated on (Table 6 & Figure 1). In the rainy season, all the 4 physical land use stream parameters measured also registered values within the acceptable limit. Water pH with a minimum value of 5.8 and maximum value of 9.8 had an average value of 7.547, EC recorded a mean value of 87.5μS/cm, TDS had a mean of 27.786mg/L and temperature an average of 17.171 °C. These values tally with the standard values of 6.5 to 8.5 for pH, 500μS/cm, for EC, 500mg/L TDS and 30 °C for temperature with a percentage compliance with WHO standards of 35.7 and, 42.9 for dry and rainy seasons respectively while EC, TDS and temperature had a compliance percentage of 100 (Table 6). The values of EC, TDS and temperatures for all the 7 land use streams were observed to be below the WHO 2011 standard of 500μS/cm, 500Mg/L and 30 °C. Although the values were far below the WHO 2011 guideline standard, rainy season downstream TDS values were generally higher than those upstream. This is due to the altering effects of land use/cover on the physical elements of stream water in the Bamboutos watershed area.

Water Quality Index (WQI) Analysis of Streams in the Bamboutos Watershed

The Water Quality Index assessment was done based on the summary of physical water parameters tested. This was then employed to assess the spatial and seasonal suitability of water within the 7 land use streams in the Bamboutos watershed area. The higher the value, the more suitable the water is, with less threat to the overall water quality. Water Quality Index range from 95 to 100 was ranked excellent signifying the absence of virtual threats in the water body. The index value drops with depreciating water quality. An index value range of 0 to 44, signifies poor water quality, a condition that departs from the natural desirable level. The results obtained from the calculation of downstream and upstream water quality index in the Bamboutos watershed area are presented in Table 9 & Figure 2.

Figure 3:Water Quality Index for 7 Sampled Streams Source: Field work (2022) (ST1 Savannah land use stream, ST2 Savannah/eucalyptus land use stream, ST3 Natural forest land use stream, ST4 Gallery forest land use stream, ST5 Wetland use stream, ST6 Settlement land use stream and ST7 Mixed land use stream).

Table 9:Water Quality Index Values for all Sampled Streams in the Bamboutos watershed area. CCME WQI: 95-100 (Excellent); 80-94 (Good); 65-79 (Fair); 45-64 (Marginal); 0-44 (Poor). Source: Field Data (2022).

Table 7 illustrates variation in Water Quality Index (WQI) values for upstream and downstream during the dry and rainy season. Results revealed higher upstream values over downstream values. Except for settlement and mixed downstream land use with marginal status values of 52.079 and 61.078 respectively and their corresponding upstream fair status values of 68.333 and 76.272, savannah land use stream, savannah/eucalyptus land use stream, natural land use stream, gallery land use stream and wetland land use stream had good WQI status both downstream and upstream. Such marginal quality status is an indication of frequent threats to water quality parameters for streams within the settlement and mixed land by land use/cover activities carried within the vicinity of the stream channels.

The fair upstream status of these land use areas suggests that land use activities within these vicinities are usually protected but occasionally threatened, with conditions that sometimes depart from desirable levels. The other land use streams had good WQI values that ranged from 80 to 94. Savannah/eucalyptus, natural forest, gallery forest and wetland land use downstream and upstream sample points had good water quality. Gallery forest land use stream had the best water quality index values of 93.871 and 93.177, both down and upstream followed by wetland upstream value (93.172). Settlement downstream was the most polluted land use stream (52.072), followed by mixed land use stream (61.078). It was generally observed that downstream land use streams had lower WQI values than upstream values. This finding is in line with that of Usongo & Bryan [25], who observed that there is greater disturbance of stream water at points of dominant human activities than at the source or upstream points. Water quality Index results of 5 out of the 7 land use streams in the Bamboutos watershed revealed a good status and similar to the result of Jose et al, (2024), who’s WQI for Acacia’s River also fell in the good category, but with a lower quality index average of 71.01 as compared to 91.148 average of streams in the Bamboutos watershed.

The implementation of land use control measures within the sub-drainage basins characterised by activities such as dumping waste in streams, washing of dresses, cars, bikes in streams, discharge of animal waste from slaughterhouses in stream channels, will go a long way to improve the water quality within the environment of the various streams. Re-enforcement of land restoration measures along stream 1 to 5 channels will contribute not only to the maintenance of their water quality but also boost the quality [31].

Conclusion

The Bamboutos watershed has a total of 8 land use/cover classes that affect stream water quality in the area. The cultivation of grains and tubers, market gardening farms and tea coffee plantations constituted agricultural primary class. Forest grassland, bare soils and water bodies came under natural land cover primary class; and build up area made up the settlement class. The main objective of this study was to examine the extent of physical surface water parameters variability due to land use/cover changes in the Bamboutos Watershed. Result revealed that the watershed is under intense mutation from land use/cover activities. The activities responsible for this are; arable farming, grazing and settlement.

The implications of land use/cover changes on stream water characteristics in the area were evident in higher physical water element values downstream compared to those upstream. The downstream pH and electrical conductivity values for all the 7 streams sampled were higher than those at upstream. Total dissolved solids values of 6 downstream, and water temperatures of 5 downstream values were also higher than their corresponding upstream values. Although water quality index for 5 were considered to be good, there is need for the implementation of land use/cover management strategies geared toward surface water protection. It can therefore be concluded that changes in surface water characteristics in the Bamboutos watershed area are attributed to changes in land use/cover.

Recommendation

In line with results obtained from the findings of this work,

the following recommendations have been proposed in order to

guarantee the sustainability of the Bamboutos watershed streams

A. The municipal councils of Babadjou, Batcham and Mbouda

in collaboration with the Divisional Delegations of: Urban

Development and Housing; Environment, Nature’s Protection

and Sustainable Development; Agriculture and Rural

Development; Energy and Water Resources and the Delegation

of Forestry and Wild under auspices of the Senior Divisional

Officer of Bamboutos and his sub-divisional collaborators

should come out with a common land use /cover zonation

for the Bamboutos watershed. This should be accompanied

by stringent enforcement of laws that governs land use

planning regulation in watershed areas. This should be done

in collaboration with traditional authorities and the local

population whose livelihood depends on this watershed area.

This will minimize the occurrences of land use conflicts in the

area.

B. The administrative authorities of this watershed area

should put in place measures that will implement watershed

restoration and protection policies. Such policies should

address environmental issues arising from unsustainable land

use practices that adversely alter and degrades water and

water resources in this area.

C. The re-enforcement of policy measures should be accompanied

by sensitization and communication strategies/campaigns on

the importance of environmental friendly practices and the

dangers of degradation livelihood activities.

D. Encouraging research and investment on possible in-situ

transformation units that will provide alternative employment

to the locals who highly depend on resources of this

watershed for survival will minimize their total reliance on

watershed degenerative livelihood activities in the area. This

may contribute in reducing the concentration on livelihood

activities that are dependent on land and water resources of

the area. The creation of Agro-Industries in this area could be

done by economic entrepreneur in collaboration with local

councils in the area.

E. The release and judicious use of National Environment and

Development Fund to sponsor projects that contribute in the

restoration of the Bamboutos watershed area will be vital.

Research on organic chemicals and soil boosting nutrients with

equivalent effectiveness of synthetic chemicals and fertilizers.

This will reduce the quantity of pollutants that end up in water

sources. Experimental farms could be created in the area by

the ministry of agriculture and Rural Development through the

Divisional Delegation. The local farming population should also

be empowered on the production of natural pest combating

substances and soil quality boosting nutrients.

F. Land use degradation activities should be prohibited or

discourage by investigating on possible strategies of imposing

sanctions on violators by local authorities in collaboration

with forces of law and order. This will address the issue of

insistence on unfriendly environmental livelihood activities.

G. An integral watershed management council should be created

in each municipality in the area. The board should be given

the task to oversee activity that go against environmental

resource preservation. They should be empowered to sanction

degraders and polluters of watershed resources according to

the law in force.

References

- WHO (2011) Guidelines for drinking water quality, (4th edn), Geneva, Switzerland.

- Munthali MG, Mustak S, Adeola A, Botai J, Singh SK, et al. (2020) Modelling land use and land cover dynamics of Dedza district of Malawi using hybrid cellular automata and markov model. Remote Sensing Applications: Society and Environment 17: 100276.

- Balgah SN (2010) Declining sustainability of pastoral management in the Menchum valley, Cameroon. International Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences 3(2): 114-123.

- Winkler K, Fuchs R, Rounsevell M, Herold M (2021) Global land use changes are four times greater than previously estimated. Nature Communication 12(1): 2501.

- Bryan BA, Lei Gao, Yanqiong Ye, Xiufeng Sun, Jeffery D Connor, et al. (2018) China’s response to a national land-system sustainability emergency. Nature 559(7713): 193-204.

- Oswalt SN, Smith WB, Mines PD, Pugh SA (2020) Forest resources of the United States 2017: A technical document supporting the forest service 2020 RPA. General Technical Report, Washington DC, USA.

- Ramankutty N, Heller E, Rhemtulla J (2010) Prevailing myths about agricultural abandonment and forest regrowth in the United States. Ann Assoc Am Geographers 100(3): 502-512.

- Leemhuis C, Thorneld F, Nischem K, Steinbach S, Muro J, et al. (2017) Sustainability in the food and water ecosystem nexus. The role of land use and land cover change for water resources and ecosystems in the Kilombero wetland Tanzania. Sustainability 9(9): 1513.

- Abdualai TA, Dzigbodi BA, Bernard NB (2020) Effect of land use and land cover changes on water quality in the Nawuni Catchment of the white Volta Basin, Northern Region, Ghana. Applied Water Science 10: 1-14.

- Khan A, Khan HH, Umar R (2017) Impact of land use on ground water quality: GIS-based study from an alluvia aquifer in the western Ganges basin. Apple Water Sci 7(8): 4593-4603.

- UN-Habitat & HIS- Erasmus University Rotterdam (2018) The states of African cities 2018-the geography of Africa investment.

- Tchindjang A, Saha F, Voundi E, Mbevo FP, NGO MR, et al. (2020) Land use and Land cover changes in centre region of Cameroon. Preprnits.

- FAO (2019) The state of the world forest, part way to sustainable development. Rome, Italy, p. 118.

- Olusola A, Onafeso O, Durowoju OS (2018) Analysis of organic matter and carbonate mineral distribution in shallow water surface sediments. Osun Geogr Rev 1(1): 106-110.

- Usongo A Patience (2024) Evaluating community perception of forest conservation policies and impact on land cover change towards Sustainable Management of Mount Cameroon National Park. Environ Anal Eco Stud 12(2): 1420-1431.

- Vorosmarty SG, Mclntyre PB, Gessner MO, Dudgeon D, Prusevich A, et al. (2010) Global threats to human water security and river biodiversity. Nature 467(10): 555-561.

- Kaffo C, Fongang G (2009) Agricultural and societal issued water issues in the Bamboutos mountains (Cameroon). Cahiers Agricultures 18(1): 17-25.

- Shancho B (2017) Discover Mt Bamboutos: Cameroon’s key watershed with high biodiversity near extinction. Environment and Rural Development Foundation (ERuDeF), Cameroon.

- Bergl RA, Oates JF, Fotso R (2007) Distribution and protected area coverage of endemic taxa in West Africa’s Biafran forest and highlands. Biological Conservation 13(4): 195-208.

- Ngoufo R (2014) Document preliminary draft of the participatory development, conservation and restoration of degraded forest areas in the Bamboutos Mountains region (Ouest-Cameroun). MINFOF/OIBT.

- Kengnil L, Tekoudjou H, Tematio P, Pamo Tedonkeng E, Tankou CM (2009) Rainfall variability along the southern flank of the Bamboutos Mountain (west Cameroon). Journal of the Cameroon Academy of Sciences 8(1): 48-52.

- Ewane BE, Asabaimbi D, Njiaghait YM, Louis N (2021) Agricultural expansion and land use land cover changes in the Mount Bamboutos landscape, Western Cameroon: Implications for local land use planning and sustainable development. International Journal of Environmental Studies 10(1): 9-11.

- Ndenecho EN (2007) Upstream water resource management strategy and stakeholder participation. Lesson in the North Western Highlands of Cameroon. AGWECAMS Printers, Bamenda, Cameroon.

- Maprasit S (2021) Physical-chemical properties relationship of Pattani river and implication for water quality monitoring study and academic service. J Phys Conf Ser 1835: 012112.

- Usongo PA, Briyan A (2021) An assessment of the spatio temporal dynamics of potable water delivery for water resource management on the south eastern flank of mount Cameroon. Int J Environ Sci Nat Res 28(3): 1-16.

- Camara M, Jamil NR, Abdullah AFB (2019) Impact of land uses on water quality in Malaysia: A review. Ecol Process 8(10): 17-19.

- Peng S, Yan Z, Zhanbin L, Peng L, Guoce X (2017) Influence of land use and land cover patterns on seasonal water quality at Multi- Spatial Scale. CATENA 151: 182-190.

- Banner E, Stahl A, Dodds W (2009) Stream discharge and riparian land use influence in-stream concentrations and loads of phosphorus from central plains watersheds. Journal of Environmental Management 44(3): 552-565.

- Siyue L, Sheng G, Wenzhi L, Hongyin H, Quanfa Z (2008) Water quality in relation to land use and land cover in the upper Han River basin, China. Catena 75(2): 216-222.

- Strilent C, Satika B (2017) Impact of and use changes on watershed discharge and water quality in a large intensive agricultural area in Thailand. Hydrological Sciences Journal 63(9): 1386-1407.

- Ngouffo R (2014) Participatory development, conservation and restoration of degraded forest areas in the Bamboutos Mountains region. Republic of Cameroon.

© 2024 © Samgwa Innocent. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)