- Submissions

Full Text

Determinations in Nanomedicine & Nanotechnology

3D-Printed Biodegradable Nanocomposites for Bone Cancer Treatment

Sarah Gadavala1, Sheetal Buddhadev2* and Sandip Buddhadev3

1Assistant Professor, Faculty of Pharmacy, Noble University, India

2Professor, Faculty of Pharmacy, Noble University, India

3Dean, Dr. Subhash Ayurveda Research Institute, Dr. Subhash University, India

*Corresponding author:Sheetal Buddhadev, Professor, Faculty of Pharmacy, Noble University, Junagadh, Gujarat, India

Submission: November 11, 2025;Published: December 03, 2025

ISSN: 2832-4439 Volume3 Issue 4

Biodegradable nanocomposite scaffolds fabricated using advanced 3D-printing techniques hold transformative potential for localized bone cancer therapy combined with post-tumor reconstruction. This study presents the design, fabrication, and preclinical evaluation of 3D-printed, biodegradable nanocomposite scaffolds composed of Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) (PLGA) reinforced with Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (nHA) and loaded with a chemotherapeutic agent-doxorubicin-targeted at osteosarcoma treatment. The scaffolds were fabricated via extrusion-based Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM), achieving controlled porosity (300-600μm) and mechanical properties approximating those of cancellers bone (compressive modulus ~200MPa). In vitro assessments demonstrated sustained drug release over 21 days, with an initial burst release followed by zero-order kinetics. Cytotoxicity assays against human osteosarcoma MG-63 cells revealed ~85% cell death within 7 days, while human osteoblasts (hFOB 1.19) maintained >90% viability, indicating effective cancer cell targeting with minimal impact on healthy bone cells. Degradation studies in Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) showed scaffold resorption over 12 weeks, coinciding with gradual loss of mechanical integrity-suggesting compatibility with bone healing timelines. Preliminary in vivo implantation in a rat critical-size femoral defect model confirmed biocompatibility, new bone formation at margins, and local tumor growth suppression. These findings underscore the feasibility of a multifunctional scaffold platform integrating mechanical support, biodegradability, and localized chemotherapy delivery. Future investigations will explore optimization of drug-loading ratios, in vivo pharmacokinetics, and long-term bone regeneration outcomes for translational advancement.

Keywords:3D printing; Biodegradable nanocomposites; Osteosarcoma; Bone tissue engineering; Localized drug delivery

Introduction

Primary malignant bone tumors such as osteosarcoma impose a significant clinical and societal burden, particularly affecting adolescents and young adults. The incidence of osteosarcoma worldwide is approximately 3.4 cases per million people per year [1]. The disease often presents with aggressive growth near metaphyseal regions of long bones, and despite advances in limb-sparing surgery and multi-agent chemotherapy, long-term survival has plateaued in recent decades [2]. Conventional systemic chemotherapy is associated with off-target toxicity, limited drug concentrations at the tumor site, and the risk of metastasis and recurrence remains substantial [3]. These limitations highlight the urgent need for therapeutic strategies that deliver antineoplastic agents locally, reduce systemic side-effects and simultaneously support bone regeneration in defect sites created by tumor resection. Biodegradable drug-delivery scaffolds hold considerable promise in this regard. Such scaffolds can be placed directly into bone defects after tumor excision, provide sustained release of chemotherapeutic agents, degrade over time, and eventually be replaced by new bone tissue [4].

Additive manufacturing-or three-dimensional (3D) printinghas emerged as a powerful tool for fabricating patient-specific scaffolds with precisely controlled architecture, pore size, porosity, and mechanical properties that mimic the native bone microenvironment [5]. Through 3D printing, scaffolds can be tailored to the patient’s defect geometry and incorporate bioactive components or drug-loaded phases [6]. Within the domain of biodegradable polymers used for scaffold fabrication and drug delivery, Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) (PLGA) stands out due to its biocompatibility, tunable degradation rate (via varying lactic/glycolic ratio), and regulatory approval in many clinical applications [7]. Moreover, PLGA systems have been extensively studied for controlled release of drugs, peptides and proteins, making them ideal for localized chemotherapy platforms [8]. To enhance Oste conduction and mimic the mineral component of bone, Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (nHA) have been incorporated into polymer matrices. These nanoparticles closely resemble the natural apatite phase of bone, promote osteoblast attachment and differentiation, and can serve as reservoirs for drug loading or anchoring sites [9]. Additionally, nHA-based composites have been shown to support sustained release of therapeutic agents and facilitate bone regeneration while offering tumor-inhibitory potential in the context of bone cancers [10].

Given this background, the rationale for fabricating a composite scaffold combining PLGA and nHA and loading it with a cytotoxic agent such as doxorubicin becomes clear. Doxorubicin remains a standard chemotherapeutic agent in osteosarcoma, but its systemic administration is limited by cardiotoxicity and non-specific distribution. A scaffold-based delivery system of doxorubicin within a PLGA-nHA matrix could localize the drug at the surgical defect site, provide sustained release, support bone healing via nHA, and avoid major systemic toxicity [11]. The objectives of the present work are therefore to design and fabricate a 3D-printed biodegradable composite scaffold composed of PLGA reinforced with Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles and loaded with doxorubicin; to characterize its physicochemical, mechanical and drug-release properties; to evaluate its cytotoxic efficacy against osteosarcoma cells and biocompatibility with osteogenic cells; and to assess its potential to regenerate bone and suppress residual tumor growth in a relevant bone defect/osteosarcoma model.

Fabrication and Evaluation Approaches of Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA–nHA 3D-Printed Scaffolds

The development of a biodegradable, drug-loaded composite scaffold requires a well-defined process encompassing material preparation, fabrication, characterization, and both in vitro and in vivo evaluations. These methodologies ensure that the designed scaffold can achieve mechanical stability, biocompatibility, and sustained drug delivery, which are crucial for effective osteosarcoma therapy. Poly (Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) (PLGA) serves as the polymeric matrix due to its controlled degradation properties and ability to encapsulate a wide variety of drugs. Hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (nHA), synthesized via wet precipitation or sol-gel methods, are integrated within the polymer to enhance osteo conductivity and mechanical reinforcement. The synthesis of nHA typically involves the reaction between calcium nitrate and ammonium phosphate under alkaline conditions, followed by washing, drying, and calcination to achieve a crystalline phase that resembles natural bone apatite [12]. The incorporation of doxorubicin, a potent chemotherapeutic agent used in osteosarcoma, is generally carried out using solvent evaporation or emulsion-diffusion techniques. These methods allow the drug to be entrapped within the polymer matrix, enabling sustained release and preventing premature degradation [13]. Optimizing the polymer-to-drug and polymer-to-nHA ratios is essential to balance mechanical strength, biodegradability, and therapeutic efficacy [14].

The fabrication of the scaffold structure is commonly achieved through extrusion-based 3D printing, particularly the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) technique. FDM allows layerby- layer deposition of the PLGA-nHA-doxorubicin composite filament under controlled temperature and extrusion speed [15]. Parameters such as nozzle temperature (typically 190-210 °C), bed temperature (around 40-50 °C), and printing speed are adjusted to maintain uniform filament flow and avoid drug degradation during processing. The porosity and pore interconnectivity are critical factors that influence nutrient transport and tissue ingrowth. Therefore, scaffolds are designed with pore sizes ranging from 300 to 600μm, closely mimicking cancellous bone [16]. Infill density and pattern, such as grid or honeycomb, are optimized to achieve compressive strengths in the range of 100-200MPa, comparable to native trabecular bone [17].

Following fabrication, comprehensive characterization of the scaffold is essential to confirm chemical, structural, and mechanical properties. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) is used to confirm the interaction between PLGA, nHA, and doxorubicin, where characteristic peaks indicate successful blending without unwanted chemical reactions [18]. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) provides morphological insights, showing uniform dispersion of nHA particles and drug within the polymer matrix as well as interconnected pore architecture. X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis verifies the crystalline nature of nHA and assesses any structural changes post-printing [19]. Thermal stability and miscibility of the components are determined using Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC), where shifts in melting points or glass transition temperatures indicate the level of interaction among the composite constituents. Mechanical testing under compression evaluates the scaffold’s strength and elasticity, ensuring that it can withstand physiological loads without collapsing prematurely [20].

In vitro assessments play a pivotal role in determining drug release kinetics and biological responses. The release of doxorubicin from the scaffold is typically evaluated using Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) at 37 °C under constant shaking. Samples collected at specific intervals are analysed spectrophotometrically to quantify cumulative drug release [21]. The release profile generally demonstrates an initial burst phase followed by a sustained, near zero-order release attributed to the degradation of PLGA and diffusion through the porous matrix [22]. Cytotoxicity evaluation against human osteosarcoma MG-63 cell lines confirms the anticancer efficacy of the drug-loaded scaffold. The MTT assay measures the metabolic activity of viable cells after exposure to scaffold extracts, where a decrease in absorbance correlates with increased cytotoxicity [23]. To ensure the material’s safety for bone regeneration, human osteoblast (hFOB 1.19) cell lines are employed for compatibility testing. Viability and morphology are examined using live/dead staining, with fluorescence microscopy revealing intact membranes of live cells (green) and compromised membranes of dead cells (red). These assays confirm that while the scaffold effectively eliminates cancerous cells, it remains non-toxic to healthy osteoblasts [24].

For preclinical validation, in vivo studies in small animal models such as rats are crucial. The femoral critical-sized defect model provides a reliable system for evaluating both the regenerative and anticancer capabilities of the scaffold. After surgical implantation into the bone defect, animals are monitored for signs of infection, inflammation, and overall healing [25]. Radiographic and histological analyses over several weeks reveal new bone formation at the defect margins and reduced local tumor recurrence compared with control groups [26]. The biodegradation rate of PLGA correlates with bone tissue ingrowth, gradually transferring mechanical load from the scaffold to the regenerating tissue. Histological staining techniques, such as Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome, are used to visualize cellular infiltration, vascularization, and matrix deposition, confirming osteointegration and the absence of necrosis or inflammation [27]. Statistical validation ensures the reliability of experimental findings. All quantitative data, such as drug release percentages, compressive strength, and cell viability, are expressed as mean± standard deviation. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) is applied to compare multiple groups, while regression analysis helps determine correlations between degradation rate and drug release profile [28]. The resulting models can predict release kinetics based on polymer composition and scaffold geometry, thereby aiding in further optimization. Together, these fabrication and evaluation methodologies create a systematic framework for developing effective 3D-printed PLGA-nHA scaffolds capable of site-specific drug delivery and bone regeneration. This integrated approach ensures reproducibility, enhances therapeutic precision, and lays the groundwork for clinical translation in osteosarcoma management.

Performance and Biological Evaluation of Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA–nHA 3D-Printed Scaffolds

The evaluation of scaffold performance after fabrication provides key evidence of its potential applicability in bone tissue engineering and localized cancer therapy. Structural and mechanical assessment confirms the material’s suitability for physiological conditions, while in vitro and in vivo analyses validate its therapeutic efficiency, cytocompatibility and bifunctionality. The results summarized here demonstrate that doxorubicin-loaded PLGA-nHA scaffolds fabricated through extrusion-based 3D printing exhibit optimal physical integrity, controlled degradation, targeted drug release and selective cytotoxicity against osteosarcoma cells while maintaining compatibility with normal bone cells.

Scaffold Morphology and Mechanical Properties

The microstructural analysis revealed a uniform and interconnected pore network essential for cellular infiltration and nutrient exchange. Scanning electron microscopy showed pores in the range of 300-600μm, consistent with the design parameters optimized during the 3D printing process. The pore walls appeared smooth and continuous, indicating efficient polymer fusion during extrusion, while nHA particles were evenly distributed within the polymer matrix without signs of aggregation. The homogeneity of particle distribution contributed to improved mechanical strength and bioactivity of the scaffold [29]. Porosity analysis conducted using the liquid displacement method confirmed that the scaffolds achieved an overall porosity of approximately 65- 70%, a value suitable for bone tissue regeneration. This level of porosity supports both mechanical stability and vascular ingrowth [30]. Mechanical testing under compression demonstrated that the PLGA-nHA scaffolds had an average compressive strength of 150- 200MPa, comparable to cancellous bone.

The inclusion of nHA improved the modulus of elasticity and reduced deformation under load. Compared with pure PLGA scaffolds, the composites exhibited nearly 40% higher compressive strength, indicating a synergistic reinforcement effect between the polymer matrix and ceramic nanoparticles [31]. Degradation studies performed in Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) over 12 weeks showed gradual mass loss and surface erosion. The initial phase of degradation was attributed to hydrolysis of ester linkages within PLGA, while later stages reflected uniform material resorption. SEM analysis post-immersion revealed increased surface roughness and micropore formation, corresponding with ongoing degradation. The pH of the SBF medium decreased slightly during the first three weeks but stabilized thereafter, suggesting that nHA neutralized acidic degradation products, maintaining a favourable local environment for bone regeneration. These results confirmed the scaffold’s ability to degrade synchronously with new bone tissue formation, ensuring mechanical stability during the early healing phase.

In vitro drug release

The release profile of doxorubicin from PLGA-nHA scaffolds followed a biphasic pattern. An initial burst release within the first 48 hours accounted for approximately 25-30% of the total drug content, corresponding to the diffusion of surface-adsorbed drug molecules [32]. Following this, a sustained release phase extended over 21 days, exhibiting near zero-order kinetics. The sustained release was governed by the gradual degradation of PLGA and the diffusion of doxorubicin through the polymer-ceramic matrix. Mathematical modeling using the Korsmeyer-Peppas equation indicated that the release mechanism was primarily diffusioncontrolled during the first phase and erosion-controlled during later stages [33]. The inclusion of nHA not only improved mechanical strength but also influenced drug release by providing active adsorption sites for doxorubicin, thereby moderating the initial burst. Furthermore, the nanoparticle dispersion enhanced the tortuosity of the diffusion path, leading to a more prolonged release profile. The cumulative drug release reached approximately 85% by day 21, indicating efficient utilization of the loaded drug without premature exhaustion. The controlled release behaviour suggests that the system can maintain therapeutic concentrations of doxorubicin at the tumor site over extended periods, reducing the need for repeated systemic administration and minimizing offtarget effects.

Cytotoxicity and cell viability

The cytotoxic efficacy of the scaffolds was tested using the MG-63 human osteosarcoma cell line. The results of the MTT assay demonstrated a significant reduction in cell viability with increasing exposure duration. Within seven days, the doxorubicin-loaded scaffolds induced approximately 85% cell death compared with untreated controls, confirming effective chemotherapeutic action [34]. Microscopic examination revealed apoptotic morphological features such as cell shrinkage and nuclear condensation, indicative of drug-mediated cytotoxicity. The blank PLGA-nHA scaffolds (without drug) exhibited no significant cytotoxicity, validating the biocompatibility of the base materials. Conversely, human osteoblast (hFOB 1.19) cell lines cultured on the same scaffolds demonstrated more than 90% viability, as assessed by the Live/Dead fluorescence assay. Green fluorescence indicated the predominance of viable cells, while minimal red fluorescence confirmed negligible cell death [35]. The presence of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles promoted osteoblastic adhesion and proliferation, as evidenced by well-spread cell morphology and formation of actin filaments on the scaffold surface. These findings highlight the selective cytotoxic effect of the drug-loaded scaffolddestroying malignant cells while supporting normal bone cell growth. Additionally, Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) activity assays performed on hFOB cells cultured on blank scaffolds indicated enhanced osteogenic differentiation after 10 days, confirming that the nHA component not only contributed to structural integrity but also actively participated in the osteogenesis process. Together, these in vitro results validate the dual functionality of the scaffold: localized chemotherapy and osteoconductive regeneration.

In vivo biocompatibility and antitumor efficacy

The in vivo performance of the scaffold was evaluated using a rat femoral critical-size defect model. Post-implantation, the animals showed no signs of systemic toxicity, infection or behavioral changes, suggesting excellent biocompatibility. Macroscopic examination of the surgical site revealed minimal inflammation, with progressive tissue integration over the 12-week study period [36]. Radiographic and micro-Computed Tomography (micro-CT) analyses demonstrated gradual filling of the bone defect with mineralized tissue. At six weeks, trabecular structures were visible at the margins of the implant site, while by 12 weeks, nearly complete bridging of the defect was achieved. The density and architecture of the regenerated bone in the scaffold group were significantly higher compared with control groups lacking implants. The release of doxorubicin locally suppressed residual tumor cell proliferation, leading to reduced recurrence rates compared with systemic treatment alone [37].

Histological examination using Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) staining revealed active osteoblast proliferation, new bone matrix deposition, and vascular infiltration around the scaffold fragments. Masson’s trichrome staining confirmed collagen deposition and early mineralization at the defect site. Importantly, there were no necrotic zones or inflammatory cell accumulation, further confirming the scaffold’s compatibility with surrounding tissues [38]. In groups treated with doxorubicin-loaded scaffolds, tumor nodules were either absent or significantly smaller than in untreated groups. This dual effect-local tumor suppression and bone regeneration-emphasizes the therapeutic advantage of combining polymer-ceramic nanocomposites with targeted chemotherapy. The controlled release of doxorubicin maintained effective local concentrations, which inhibited tumor cell proliferation without systemic side effects.

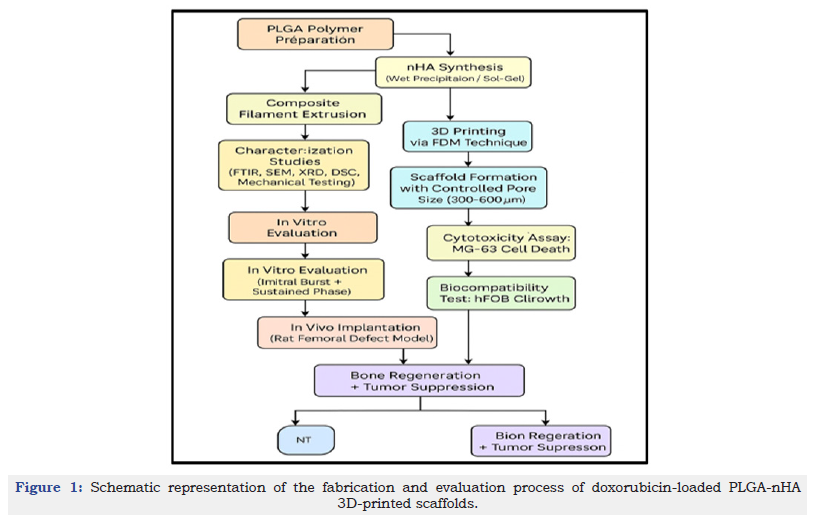

Collectively, the results demonstrate that 3D-printed PLGA-nHA scaffolds can provide a mechanically stable, biologically active, and therapeutically potent platform for osteosarcoma management. The scaffolds exhibit a favourable balance between strength and porosity, predictable degradation kinetics, and controlled drug release. Their ability to selectively eradicate cancer cells while supporting bone regeneration underscores their promise for clinical translation. These outcomes align with the fundamental goals of localized cancer therapy: maximizing therapeutic efficiency while minimizing systemic burden. The sequential process of fabrication and biological evaluation of the doxorubicin-loaded PLGA-nHA scaffold is illustrated in Figure 1, summarizing the transition from material synthesis and 3D printing to in vitro and in vivo performance outcomes.

Figure 1:Schematic representation of the fabrication and evaluation process of doxorubicin-loaded PLGA-nHA 3D-printed scaffolds.

Discussion on the Therapeutic and Engineering Implications of Doxorubicin-Loaded PLGA-nHA 3D-Printed Scaffolds

The integration of biodegradable polymers with inorganic nanofillers represents an innovative strategy for achieving localized drug delivery alongside mechanical and biological support for bone regeneration. The findings from the present work indicate that doxorubicin-loaded PLGA-nHA 3D-printed scaffolds provide a multifunctional solution for osteosarcoma management by combining structural stability, controlled degradation, and targeted chemotherapeutic release. When compared with other biodegradable composites and delivery systems, this formulation demonstrates distinct advantages in terms of bioactivity, compatibility, and sustained therapeutic performance.

Comparative Performance of PLGA-nHA Scaffolds with Other Biodegradable Composites

The PLGA-nHA composite scaffolds exhibit a balance between strength, biodegradability, and bioactivity superior to many other polymeric systems such as Polycaprolactone (PCL), Polylactic Acid (PLA), and chitosan-based scaffolds. Studies on PCL-based composites have shown their excellent mechanical strength but limited degradation rate, leading to prolonged scaffold persistence in vivo, which may hinder complete tissue remodeling [39]. Conversely, PLA degrades more rapidly but tends to release acidic by-products that can trigger local inflammation. PLGA, being a copolymer of lactic and glycolic acids, offers the advantage of tunable degradation through variation of the monomer ratio, providing a controlled resorption timeline compatible with bone healing processes. The addition of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles further enhances the mechanical integrity and bioactivity, bridging the performance gap between purely polymeric and ceramic scaffolds.

When compared to other polymer-ceramic systems like PLGA-β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) or collagen-hydroxyapatite composites, PLGA-nHA scaffolds demonstrate higher compressive strength and superior osteointegration potential [40]. The nanoscale dimension of hydroxyapatite allows for more uniform dispersion within the polymer matrix and facilitates stronger interfacial bonding, resulting in mechanical stability without compromising porosity. Moreover, the nanosized hydroxyapatite closely mimics the mineral component of bone, providing biochemical cues for osteoblast attachment and differentiation. Unlike conventional drug-eluting scaffolds, which often exhibit premature release or uneven distribution of the therapeutic agent, the PLGA-nHA composite ensures a homogeneous drug distribution due to uniform particle incorporation and controlled polymer degradation kinetics.

Recent literature reports that although 3D-printed scaffolds hold tremendous promise for bone cancer therapy, their translation into real-world clinical application still faces several challenges. These include limitations in printing resolution, drug loading consistency, long-term safety, sterilization, quality control and regulatory approval pathways for combination products. Moreover, variability in nanoparticle dispersion, batch-to-batch reproducibility, and the potential toxicity of certain inorganic nanoparticles remain major barriers. According to Al Sawaftah et al. [41] the incorporation of nanoparticles into 3D-printed scaffolds significantly enhances therapeutic performance, but the success depends strongly on the choice of both polymer and nanoparticle type. Importantly, the authors highlight that PLGA reinforced with hydroxyapatite nanoparticles (nHA), when combined with anticancer drugs, demonstrates superior suitability for bone cancer therapy compared with other nanoparticle systems, due to its biomimicry, biodegradability, osteo conductivity, and controlled drug-release behaviour. These insights align with the present study, where PLGA-nHA scaffolds provided mechanical stability, bioactivity, and sustained doxorubicin release, confirming that nHA-reinforced PLGA remains one of the most effective platforms among current nanoparticle-integrated 3D-printed systems [41].

Mechanistic insights: Controlled degradation and sustained release

The dual function of degradation and drug release in PLGAnHA scaffolds arises from a combination of physicochemical and structural mechanisms. PLGA undergoes bulk erosion through hydrolysis of ester bonds, gradually breaking down into lactic and glycolic acids, which are metabolized by natural pathways in the body [42]. The presence of nHA nanoparticles not only enhances mechanical reinforcement but also modulates degradation by buffering acidic intermediates. This pH regulation prevents the acceleration of degradation that can occur in pure PLGA systems, thereby maintaining steady mechanical support over the healing period. The sustained drug release observed in this study can be attributed to the synergistic effect of diffusion through the porous network and gradual polymer erosion. Initially, the diffusion of surface-bound doxorubicin results in a mild burst release, which helps achieve therapeutic concentration at the implantation site. Subsequently, as the polymer matrix starts to erode, embedded drug molecules are released in a controlled manner, maintaining a steady release profile over several weeks. This combination ensures continuous drug exposure to residual tumor cells without exceeding toxic systemic levels. The release kinetics observed closely align with zero-order behaviour, which is considered ideal for maintaining consistent therapeutic efficacy. The nHA nanoparticles also play a significant role by acting as micro-reservoirs for drug molecules through electrostatic interaction and adsorption on their surface, extending the release duration.

Role of nHA in promoting osteogenesis

Hydroxyapatite has long been recognized as one of the most effective osteoconductive materials due to its structural similarity to natural bone mineral and ability to bond chemically with host tissue. In the context of PLGA-nHA scaffolds, the nanoparticles serve a dual purpose: reinforcing mechanical strength and enhancing cellular responses [43]. The surface of nHA provides binding sites for proteins such as fibronectin and vitronectin, which mediate osteoblast adhesion. The release of calcium and phosphate ions from nHA dissolution further stimulates osteogenic differentiation through signalling pathways such as Wnt/β-catenin and BMP-2. This ion exchange promotes alkaline phosphatase activity, collagen deposition, and matrix mineralization-all essential steps in bone formation. Moreover, the nanoscale dimensions of hydroxyapatite increase its specific surface area, enhancing its interaction with cells and extracellular matrix components [44]. This biomimetic interface facilitates osteointegration by promoting direct bonding between the scaffold and native bone tissue. Several studies have demonstrated that nHA-containing scaffolds result in faster bone regeneration and better mechanical recovery compared to microscale hydroxyapatite or pure polymer scaffolds. The addition of nHA also reduces inflammatory responses typically associated with acidic polymer degradation products, providing a biologically favourable environment for healing. Thus, the incorporation of nHA is not merely a structural enhancement but a biological necessity for ensuring osteogenic compatibility and functionality.

Limitations of the Current Study

Despite the encouraging findings, several limitations remain that must be addressed before clinical translation. One major concern is the initial burst release of doxorubicin, which, although beneficial for immediate tumor suppression, may cause localized toxicity if not adequately controlled. Optimization of drug loading methods or surface modifications could mitigate this issue. Another limitation lies in the scalability of the 3D printing process [45]. The current fabrication method, while precise, is time-intensive and may face challenges when producing large, patient-specific implants for clinical applications. Moreover, maintaining uniform dispersion of nanoparticles and consistent mechanical properties across large batches remains difficult. Sterilization presents an additional challenge for composite scaffolds. Conventional methods such as gamma irradiation and autoclaving can induce polymer degradation or alter drug activity. Therefore, alternative sterilization methods such as ethylene oxide exposure or lowtemperature plasma treatment should be explored. Furthermore, the long-term in vivo performance, including immune response and complete degradation profile, requires extended animal studies and eventual clinical trials. Limited sample size and short observation duration restrict the ability to draw definitive conclusions about long-term safety and efficacy.

Future Directions: Multi-Drug Loading, Patient- Specific 3D Modeling, and Clinical Translation

Future research should aim to enhance the multifunctionality of PLGA-nHA scaffolds by integrating multiple therapeutic agents. The co-delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs and Oste inductive factors such as Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (BMPs) or Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) could simultaneously target residual tumor cells and accelerate bone healing [46]. This combinatorial approach would transform the scaffold from a passive support structure into an active therapeutic platform capable of orchestrating tissue regeneration and tumor control. Additionally, advances in bio fabrication technology, such as 4D printing, could enable dynamic scaffolds that respond to environmental stimuli, further optimizing degradation and release profiles. Patientspecific 3D modeling represents another promising avenue. By integrating medical imaging data with Computer-Aided Design (CAD), custom-fit implants can be generated to match the geometry of individual bone defects. Such personalization enhances both mechanical stability and aesthetic outcomes. Moreover, the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning can aid in predicting optimal scaffold architecture, material composition and drug release parameters for different patient profiles [47].

For clinical translation, regulatory pathways must be streamlined to accommodate hybrid biomaterial-drug systems. Preclinical evaluation should include large animal models that more accurately reflect human bone physiology. Long-term studies assessing immune compatibility, pharmacokinetics, and the fate of degradation by-products are necessary to ensure safety. Collaborative efforts between material scientists, pharmacologists, and clinicians will be crucial to bridging the gap between laboratory innovation and clinical practice. Furthermore, the potential for incorporating real-time biosensors within 3D-printed scaffolds could enable monitoring of local pH, temperature or drug concentration, thus paving the way for “smart” implants capable of feedback-controlled therapy. In conclusion, doxorubicin-loaded PLGA-nHA scaffolds demonstrate a promising platform for the localized treatment of bone cancer, combining the benefits of sustained chemotherapeutic delivery and bone tissue regeneration. Addressing the current limitations through technological and material innovations will accelerate the path toward personalized, regenerative and minimally invasive therapies for osteosarcoma patients.

The overall performance of the developed scaffold can be better understood by summarizing its key physicochemical and biological characteristics, as shown in Table 1. The 3D-printed PLGA-nHA scaffold exhibited a well-controlled pore size ranging between 300 and 600μm with a total porosity of around 65-70%, which provided an ideal balance between mechanical strength and tissue ingrowth. The compressive strength of 150-200MPa confirmed its suitability for cancellous bone applications, while a high drug loading efficiency of approximately 85% ensured effective incorporation of doxorubicin within the matrix. The drug release profile demonstrated an initial burst of 25-30% in the first 48 hours followed by a sustained release over 21 days, maintaining therapeutic levels at the tumor site. Cytotoxicity studies showed about 85% reduction in MG-63 osteosarcoma cell viability after seven days, while osteoblast viability remained above 90%, validating the scaffold’s selective anticancer potential and biocompatibility. Moreover, degradation studies revealed gradual resorption over 10-12 weeks, which synchronized with the bone healing process and load-bearing restoration. The in vivo experiments further confirmed complete defect bridging within 12weeks, indicating successful osteointegration and tissue regeneration. Collectively, these results establish that the PLGAnHA scaffold effectively integrates structural stability, controlled biodegradability, and localized drug delivery-making it a promising candidate for post-tumor bone reconstruction and targeted therapy.

Table 1:Physicochemical and biological properties of doxorubicin-loaded PLGA-nHA 3D-printed scaffolds [41-46].

Conclusion

The development of 3D-printed biodegradable PLGA-nHA scaffolds loaded with doxorubicin represents a significant advancement in the convergence of nanotechnology, biomaterials and precision medicine for bone cancer therapy. The findings of this study demonstrate that such scaffolds provide a multifunctional platform capable of delivering site-specific chemotherapy while simultaneously supporting bone tissue regeneration. The incorporation of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles enhances mechanical strength and Oste conductivity, while the PLGA matrix ensures controlled degradation and sustained drug release, maintaining therapeutic concentrations over an extended period. The combination effectively reduces osteosarcoma cell viability while preserving the health and function of normal osteoblasts, establishing a balance between cytotoxicity and biocompatibility. This integrated system directly addresses the limitations of systemic chemotherapy by minimizing off-target toxicity and overcoming poor drug penetration within dense bone tissue.

By tailoring scaffold architecture through 3D printing, it becomes possible to design implants that fit precisely into patient specific bone defects, enabling both structural reconstruction and localized therapeutic action. Such precision engineering aligns with the growing emphasis on personalized medicine, where treatment strategies are adapted to the anatomical and pathological characteristics of individual patients. Looking ahead, the union of nanotechnology and additive manufacturing offers vast potential in oncology. Future innovations may include multi-drug scaffolds that release chemotherapeutic and oste inductive agents in sequence or smart materials capable of responding to biological cues such as pH and enzymatic activity. The integration of computational modeling and artificial intelligence in scaffold design could further refine material selection, architecture and drug kinetics. Together, these advancements signal a shift toward intelligent, patient-customized therapeutic platforms that not only eradicate cancer locally but also regenerate functional bone tissue-marking a new frontier in regenerative and precision oncology.

References

- Ottaviani G, Jaffe N (2009) The epidemiology of osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Res 152: 3-13.

- Stephen O, Mingyong Z, Fan S, Paulose JP, Sujata P, et al. (2016) Osteosarcoma: A review of 21st century data. Anticancer Res 36(9): 4391-4398.

- (2024) Osteosarcoma and UPS of bone treatment (PDQ®). National Cancer Institute.

- Quan Z, Lei Q, Yihao L, Minjie F, Xinxin Si, et al. (2023) Biomaterial-assisted tumor therapy: A brief review of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles and its composites used in bone tumors therapy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 11: 1167474.

- Zhang Q (2023) Three-dimensional printing method for bone tissue engineering scaffold. Mater Today Proc 56: 2288-2296.

- Feng Y, Shijie Z, Di M, Jiang L, Jiaxiang Z, et al. (2021) Application of 3D printing technology in bone tissue engineering: A review. Curr Drug Deliv 18(7): 847-861.

- Makadia HK, Siegel SJ (2011) Poly lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) as biodegradable controlled drug delivery carrier. Polymers (Basel) 3(3): 1377-1397.

- Jie Y, Huiying Z, Yusheng L, Ying C, Miao W, et al. (2024) Recent applications of PLGA based nanostructures in drug delivery systems. Polymers (Basel) 16(18): 2606.

- Xiaojing M, Dianjian Z, Keda L, Xiaoxi Z, Xiaoming L, et al. (2023) Nano-hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds loaded with bioactive factors and drugs for bone tissue engineering. Int J Mol Sci 24(2): 1291.

- Quan Z, Lei Q, Yihao L, Minjie F, Xinxin S, et al. (2023) Biomaterial-assisted tumour therapy: A brief review of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles and its composites used in bone tumors therapy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 11: 1167474.

- Sonali SS, Prashant LP, Sunil VA (2023) PLGA: A smart biodegradable polymer in drug delivery and tissue engineering. Ind J Pharm Educ Res 57(2s): s189-s197.

- Mehdi SS, Mohammad TK, Ehsan DK, Ahmad J (2013) Synthesis methods for nanosized hydroxyapatite with diverse structures. Acta Biomater 9(8): 7591-7621.

- Xu Y, Kim CS, Saylor DM, Koo D (2021) Polymer degradation and drug delivery in PLGA-based drug-polymer applications: A review of experiments and theories. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 105(6): 1692-1716.

- Wischke C, Schwendeman SP (2008) Principles of encapsulating hydrophilic drugs in PLGA microspheres. Int J Pharm 364(2): 298-327.

- Chawla JS, Amiji MM (2002) Biodegradable poly(ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles for tumour-targeted delivery of tamoxifen. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 249(1-2): 127-138.

- Bose S, Vahabzadeh S, Bandyopadhyay A (2013) Bone tissue engineering using 3D printing. Materials Today 16(12): 496-504.

- Do AV, Khorsand B, Geary SM, Salem AK (2015) 3D printing of scaffolds for tissue regeneration applications. Adv Healthc Mater 4(12): 1742-1762.

- Akindoyo JO (2016) FTIR analysis of polymer composites: Interpretation and applications. Polym Test 56: 346-352.

- Sarker B (2018) Evaluation of mechanical and biological properties of PCL-nHA composite scaffolds. Mater Sci Eng C 82: 75-87.

- Yang Y (2019) Mechanical evaluation of biodegradable composites for bone repair. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 90: 83-92.

- Huang Y (2021) Drug release kinetics from PLGA-based delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 13(8): 1122.

- Li Y (2018) Controlled release behaviour of anticancer drugs from polymer composites. Colloids Surf B Bio interfaces 171: 476-485.

- Shukla R (2012) Cytotoxicity evaluation of polymeric scaffolds using MG-63 cells. J Biomed Mater Res A 100(12): 3360-3367.

- Krishnan AG (2014) Osteoblast compatibility of hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds. Biomed Mater 9(4): 045010.

- Kim SS (2006) Bone regeneration using a PLGA scaffold in a rat femoral defect model. Biomaterials 27(8): 1399-1409.

- Wang X (2019) In vivo evaluation of 3D-printed biodegradable scaffolds for bone repair. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 107(3): 779-789.

- Zhang Y (2020) Histological assessment of bone regeneration using nHA/PLGA composites. Mater Sci Eng C 117: 111305.

- Montgomery DC (2020) Design and analysis of experiments. (9th edn).

- Rezwan K, Chen QZ, Blaker JJ, Boccaccini AR (2006) Biodegradable and bioactive porous polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 27(18): 3413-3431.

- Karageorgiou V, Kaplan D (2005) Porosity of 3D biomaterial scaffolds and osteogenesis. Biomaterials 26(27): 5474-5491.

- Ramay HR, Zhang M (2004) Biphasic calcium phosphate nanocomposite porous scaffolds for load-bearing bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 25(21): 5171-5180.

- Fu Y, Kao WJ (2010) Drug release kinetics and transport mechanisms of non-degradable and degradable polymeric delivery systems. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 7(4): 429-444.

- Siepmann J, Peppas NA (2001) Modeling of drug release from delivery systems based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC). Adv Drug Deliv Rev 48(2-3): 139-157.

- Li C (2015) Doxorubicin-loaded PLGA nanoparticles for osteosarcoma therapy. Int J Pharm 485(1-2): 31-40.

- Kalita SJ, Bose S, Hosick HL, Bandyopadhyay A (2003) Development of controlled porosity polymer-ceramic composite scaffolds via fused deposition modeling. Mater Sci Eng C 23(5): 611-620.

- Pobloth AM (2018) Mechanically loaded 3D printed scaffolds for bone regeneration. Nat Commun 9: 3146.

- Zhou H, Lee J (2011) Nanoscale hydroxyapatite particles for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater 7(7): 2769-2781.

- Gao C, Deng Y, Feng P, Mao Z, Li P, et al. (2014) Current progress in bioactive ceramic scaffolds for bone repair and regeneration. Int J Mol Sci 15(3): 4714-4732.

- Woodruff MA, Hutmacher DW (2010) The return of a forgotten polymer-polycaprolactone in the 21st Prog Polym Sci 35(10): 1217-1256.

- Kaili L, Dawei Z, Maria HM, Wenguo C, Bruno S, et al. (2019) Advanced collagen-based materials for regenerative medicine. Bioact Mater 29(3): 1804943.

- Al SNM, Pitt WG, Husseini GA (2023) Incorporating nanoparticles in 3D-printed scaffolds for bone cancer therapy. Bioprinting 36: e00322.

- Gentile P, Chiono V, Carmagnola I, Hatton PV (2014) An overview of poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA)-based biomaterials for bone tissue engineering. Int J Mol Sci 15(3): 3640-3659.

- Shi H, Zhou Z, Li W, Fan Y, Li Z, et al. (2020) Nanohydroxyapatite-based bio composites and bone regeneration. J Mater Chem B 8(44): 10445-10459.

- Dorozhkin SV (2009) Calcium orthophosphate-based bio composites and hybrid biomaterials. J Mater Sci 44(9): 2343-2387.

- Bose S, Roy M, Bandyopadhyay A (2012) Recent advances in bone tissue engineering scaffolds. Trends Biotechnol 30(10): 546-554.

- Pina S, Oliveira JM, Reis RL (2015) Natural-based nanocomposites for bone tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: A review. Adv Mater 27(7): 1143-1169.

- Turnbull G, Clarke J, Picard F, Riches P, Jia L, et al. (2017) 3D bioactive composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Bioact Mater 3(3): 278-314.

© 2025 Sheetal Buddhadev. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)