- Submissions

Full Text

Clinical Research in Animal Science

The Availability of the Main Feedstuffs used in Pig Feed Marketed in the Different Markets of Burundi

Joseph Butore1*, Daniel Sindaye2 and Constantin Nimbona1

1Faculty of Agronomy and Bioengineering, Burundi

2National Center for International Research on Animal Gut Nutrition, China

*Corresponding author:Joseph Butore, University of Burundi, Faculty of Agronomy and Bioengineering, Department of Health and Animal Productions, P.O. Box. 2940 Bujumbura, Burundi

Submission: September 24, 2024;Published: October 17, 2024

ISSN: 2770-6729Volume 3 - Issue 4

Abstract

A survey was conducted to evaluate the availability and variability of primary feedstuffs for pigs in Burundi’s feed markets. The one-month survey focused on the accessibility of primary feedstuffs for pigs sold in Siyoni, Cotebu, Chanic, Kinama, Rubirizi, or Kanyosha markets. The survey also involved 22 pig farmers who purchase various feedstuffs from different markets. The results show that 100% of farmers buy feedstuffs separately, and the proportions of their use vary from one pigsty to another. They incorporate crop residues into their pigs’ staple feed, supplementing it with various market-purchased feedstuffs. Corn, corn bran, wheat bran, palm kernel cake, rice bran, cotton cake, sunflower cake, soya cake, bone meal, fish meal, dried blood, limestone, salt, molasse, and sorghum are feedstuffs marketed in all markets. The average monthly selling price, sale frequency rate, and quantity of feedstuffs sold vary significantly between different markets (P < 0.05). Except for corn bran, limestone, and molasses, traders in the Cotebu market sell a higher quantity of feedstuffs compared to traders in other markets (P < 0.05). Farmers have limited numbers of pigs that they are able to manage, and 54.5% are indifferent to the profit made from pig farming.

Keywords:Feed; Pig; Market; Burundi

Introduction

Burundi is a country where animal husbandry is an activity related to agriculture and occupies a prominent place in the increase of animal products [1]. Pork is one of the animal species that provides a good source of animal protein for the Burundi population to ensure their food security [2]. Pig farming has several advantages, including high prolificity, rapid growth, production that requires little space, greater valorization of animals, vegetables, or kitchen residues, very high productivity, etc. [3-5].

Despite its numerous benefits, Burundi continues to expand pig farming across the country, with a recent focus on enhancing pig genetic resources [2]. Among the factors limiting its intensification, the scarcity of the different feedstuffs used in its diet, the high price of the different feedstuffs, and the lack of well-trained personnel, are a major challenge for increasing its productivity [6,7]. In most pigsty, the formulation of a pig ration is based on readily available local feedstuffs or crop residues, and the latter varies from one pigsty to another [8]. Few studies have been conducted in Burundi to assess the availability of the main feedstuffs intended for pork, with the aim of promoting more affordable diets that value local products and can boost productivity without compromising human health through the food chain [9,10]. It was in this context that a study was carried out on the availability of the main feedstuffs in pig feed in Burundi.

This research aims to ascertain whether pig farming in Bujumbura’s peripheral areas, where farmers purchase the majority of feed from the capital’s markets, can be considered a truly beneficial and profitable activity. Through this research, the main ingredients marketed in the market will serve as a reference base for educational programs for pig farmers. These lessons will focus on improving pig production through pig feed formulation, taking into account the value of readily available local feedstuffs to reduce the cost of pig feed in Burundi. The markets under investigation in this research were Siyoni, Cotebu, Chanic, Kinama, Rubirizi, and the Kanyosha market. These different markets were chosen because they are reference markets for the sale of feedstuffs for different animals and because even farmers in the interior of the country obtain supplies from these markets. Their proximity to the various car parks leading to the interior of the country is also a major asset in their transport to the pigsty of the interior of the country.

Materials and Methods

Data collection

The survey took place over a period of one month (February 2024) and consisted of two main parts. The first part of the survey focused on the availability of various feedstuffs that are sold in various markets for pig feed. In this context, six markets were identified in the city of Bujumbura and its surroundings, including the markets of Siyoni, Cotebu, Chanic, Kinama, Rubirizi, and Kanyosha. These different markets were chosen because even herders in the interior of the country obtain supplies from them, and because of their proximity to the various car parks leading to the interior of the country.

After identifying all the sellers of different feedstuffs used in the feed of the pig, a sheet containing all the questions related to the sale of each feedstuff was worthily completed daily throughout the investigation. These questions focus on price variability, quantity sold, and the sale frequency rate of each feedstuff or mixture of different feedstuffs. During this survey, the information collected from each seller was directly filled out on a form, and the number of forms obtained daily in each market was put together before being inputted using a computer.

Not all of these markets have the same number of feedstuff sellers for pig feed. A total of 48 sellers were identified, including 9 in Siyoni, 15 in Cotebu, 7 in Rubirizi, 7 in Kinama, 5 in Kanyosha, and the other 5 in Chanic market. In the event that the seller sells a mixed concentrate feed, the proportions of each feedstuff in the mixture should be provided to ensure that the mixed concentrate feed sold meets the standard required for feeding pigs according to their growth stage. After daily recording of information on prices, quantity sold and sale frequency of each feedstuff, the following parameters were calculated in each market using the following formulas:

Average monthly price (per kg of each ingredient) = (the total sum of the daily price of each feedstuff throughout the investigation period/total number of days in that investigation); Frequency sale rate of each ingredient = ((number of days the feedstuff was sold during the investigation period/total number of days in that investigation) x (number of sellers who sold the feedstuff during the market investigation period/total number of sellers in the market) x 100; Total quantity sold by seller of each feedstuff (kg) = the total daily quantity of each feedstuff sold by each seller during the period of investigation.

The second part consisted of a survey of pig farmers who buy various feedstuffs to feed their pigs from the various markets, and the choice of the farmer to be interviewed was conditioned by the possession of at least 10 pigs in his pigsty. The questions asked to them include the source of the various feedstuffs used in feeding their pigs, their purchase price, their nature, the number of pigs kept, and whether they buy concentrate feed that has already been mixed or whether they buy these feedstuffs separately.

If the pig farmer buys a mixed concentrate feed, the proportions of the various feedstuffs that make up the mixture are laid down to determine whether the pig farmer is feeding his pigs a balanced diet. During this phase, 22 pig farmers were interviewed on site in their pigsty. If the pig farmer purchased the ingredients separately and fed his pigs more than one feedstuff, he was asked the question of the different proportions of each feedstuff in the mixture. This second part of the investigation was conducted over 5 days (from February 13th to 17th, 2024). To compare price variability for each feedstuff, the average purchase price of each feedstuff for the day of the survey, the price over the last 30 days, and the price on the first day of February were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

The data were regularly recorded using Microsoft Excel, and the statistical analysis was done using SPSS 25 software with One- Way ANOVA using a linear polynomial model. The Duncan method was used to compare multiple means, and the statistical data was tabulated as mean ± standard error deviation, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Result

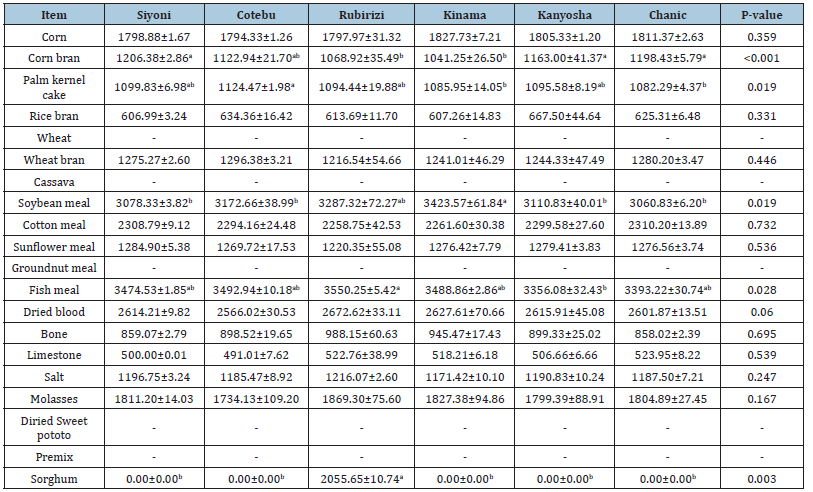

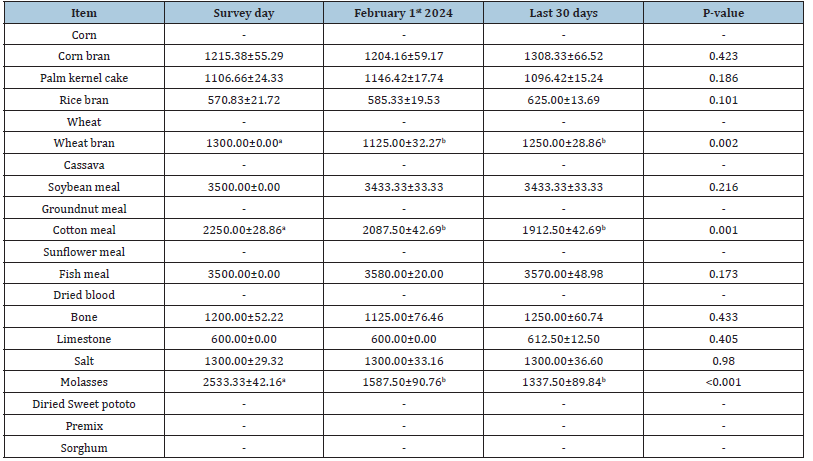

In pig farming, the price of feed is a much more important factor in the cost of production and directly affects the farmer’s profit. Table 1 shows the monthly variation in the selling price of the different feedstuffs used in pig feed in the different markets.

As shown in Table 1, there was a significant variation in the average monthly selling price of corn bran, palm kernel meal, soybean meal, fish meal, and sorghum (P < 0.05). Moreover, there are no significant differences between the average monthly selling price of corn, rice bran, wheat bran, cotton meal, sunflower meal, dried blood, bone flour, limestone, salt, and molasses (P > 0.05). Compared to other markets, the price of corn bran is higher in the Siyoni, Chanic, or Kanyosha markets and lower in the Kinama, and Rubirizi markets. Palm kernel cake prices are higher at the Cotebu market but lower at the Kinama and Chanic markets. With the exception of the Rubirizi market, the price of soybean meals is higher in the Kinama market compared to other markets. The price of fish meal is higher at Rubirizi market compared to Kanyosha market. Sorghum is only marketed in the Rubirizi market. In all markets visited, premix, dried shower potato, groundnut, cassava, and wheat cake were not sold. Numerically, some feedstuffs are more expensive than others.

Table 1:Average monthly selling price of the various ingredients used in pig feed to different markets (FBU/kg).

Note:a,bMean that there were significant differences between groups.

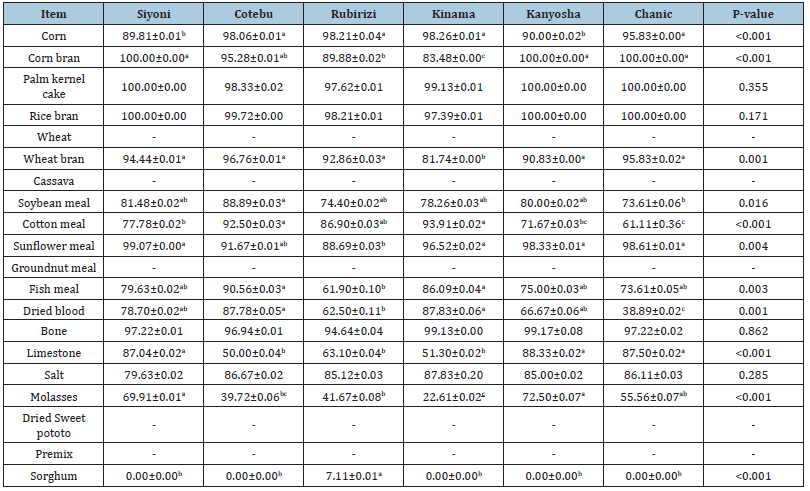

As shown in Table 2, there was a significant difference between different markets in terms of the sales frequency rate of corn, corn bran, wheat bran, soybean meal, cotton meal, sunflower meal, fish meal, dried blood, limestone, molasses, and sorghum (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the sale frequency rate of rice bran, palm kernel meal, bone meal, or salt (P > 0.05). With the exception of the sale frequency rate of limestone, molasses, and sorghum, the Cotebu market had a higher sale frequency rate of various feedstuffs compared to other markets. The Rubirizi market and the Kinama market had a lower sale frequency rate compared to other markets. Premix, dried shower potato, groundnut cake, cassava, and wheat are not sold in all markets. Given the percentage of sale frequency rate of each feedstuff, we see that despite limited resources, farmers buy almost all the ingredients. Table 3 presents the total monthly quantity per vendor of the different feedstuffs used in pig feed in the various markets.

Table 2:Sale frequency rate of the different ingredients used in pig feed to the different markets.

Note: a,b,c Mean that there were significant differences between groups.

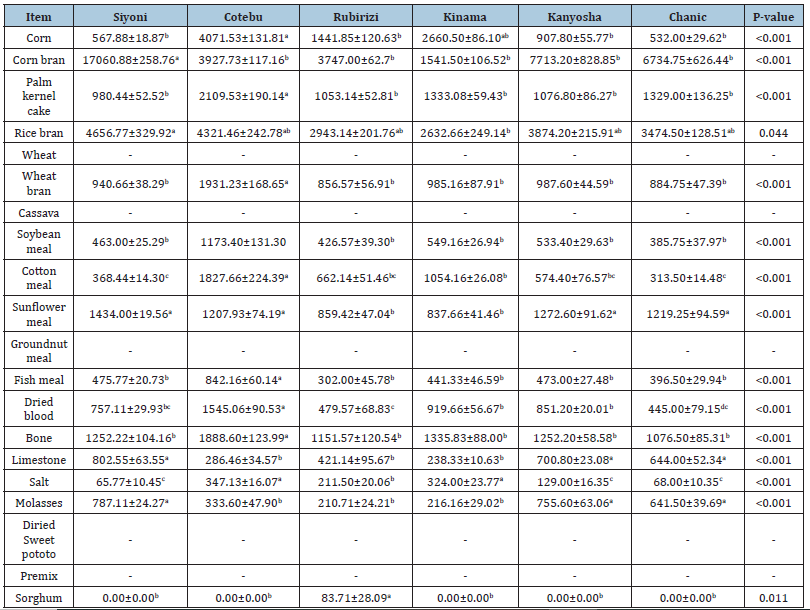

As shown in Table 3, there was a significant difference in terms of the amount of all the various feedstuffs marketed in different markets (P < 0.05). Except for corn bran, limestone, and molasses, traders in the Cotebu market sell a greater quantity of other feedstuffs than traders in other markets. Corn bran and rice bran are much more marketed in the Siyoni market than in other markets (P < 0.05). Sorghum was only sold in the Rubirizi market, but as mentioned above, premix, dried sweet potato, groundnut cake, cassava, and wheat were not sold in all markets. Numerically, each seller’s average monthly quantity sold in various markets remained lower. Table 4 shows the variation in the average price of each feedstuff used by farmers interviewed in their pig feeding over time for the investigation.

Table 3:Monthly quantity sold/trader of the various ingredients used in pig feed (kg).

Note: a,b,cMean that there were significant differences between groups.

As presented in Table 4, there was a significant difference between the prices of molasses, cotton cake, and wheat bran between the different dates considered in this survey (P < 0.05).

The price of these ingredients was revised upwards on the day of the survey compared to other dates already identified, but there is no significant difference between the price of various feedstuffs on 1/2/2024 and that of these ingredients in the last 30 days (P > 0.05). The different dates studied show no significant difference in terms of prices of corn bran, rice bran, palm kernel meal, soybean meal, fish meal, bone meal, limestone, and salt (P > 0.05). Corn, wheat, dried sweet potato, premix, sunflower meal, groundnut meal, dried blood, sorghum, and cassava were not purchased by the pig farmers interviewed. Table 5 presents the pig population, feed source, and profit margins of the pig farmers interviewed in their pigsty.

Table 4:Average purchase price of the various ingredients used in pig feed.

Note: a,bMean that there were significant differences between groups.

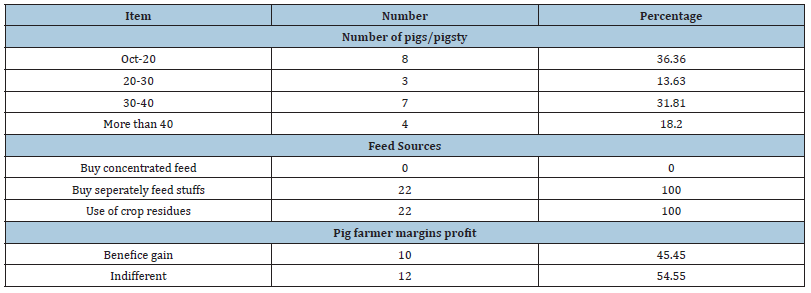

Table 5:Pig numbers, feed sources and profit margins of the farmers surveyed.

Given the number of pig farmers who have more than 40 heads, the pig farmers do not own a large number of pigs. Farmers do not buy mixed ingredients at the market or from a market outlet; they prefer to buy them separately. To supplement the various feedstuffs purchased, they use crop residues or grass that the pig can eat. In terms of profit gain from pig farming, more than half of pig farmers are indifferent.

Discussion

Pig farming in Burundi contributes enormously to the availability of animal protein for the population, despite the challenges presented by this sector. The results of this survey show that there was variability in the average monthly selling price of the various feedstuffs used in pig feed in the different markets covered by this survey. This variation is due to a high demand for these feedstuffs, as they are also used in the feed of other animals, particularly dairy cows and poultry. As with other products, trade in the various feedstuffs used in pig feed follows the law of supply and demand [11]. Burundi is an agropastoral country with extensive agriculture, leading to a shortage of food ingredients in both quality and quantity, particularly for feeding monogastric animals. Premix, dried shower potato, groundnut cake, cassava, and wheat are not marketed in all markets covered by this survey due to their limited production in Burundi and the need for industrial processing, which renders them unavailable in the various markets. Corn, corn bran, wheat bran, palm kernel meal, rice bran, cotton meal, sunflower meal, soybean meal, bone meal, fish meal, dried blood, limestone, salt, molasses, and sorghum are marketed in all markets as they are locally produced. Burundi is a country where any agricultural product is valued, and traders of livestock inputs do it as an entrepreneurial activity.

The significant variation in average monthly selling prices of corn bran, palm kernel meal, soybean meal, fish meal, and sorghum in the various markets is justified by the fact that these feedstuffs are derived from seasonal crops in Burundi. During crop harvest, the price of the residues decreases. Depending on the quality and quantity purchased, sellers of these feedstuffs lower the price as much as they can. The distance between these markets and the processing place, where traders supply them before selling, also influences the price of these feedstuffs, which is relative to the trading of other goods [12,13]. For instance, the distance between the Rubirizi market and the Kanyosha market, which is closer to Lake Tanganyika, explains why the price of fishmeal is higher at the former than the latter.

Despite their limited resources, farmers purchase all the marketed feedstuffs, as evidenced by the sale frequency rate of various feedstuffs. The Cotebu market has a higher sale frequency rate of various feedstuffs compared to other markets except for limestone, molasses, and sorghum while the Rubirizi market and the Kinama market have a lower sale frequency rate compared to other markets. Given that all the markets studied in this work are located in the city of Bujumbura, specifically the main car parks that lead to the interior of the country, the location of these markets, particularly the Cotebu and Siyoni markets, allows all farmers in the country to purchase these feedstuffs at the appropriate time. This situation of market location is similar to other markets in different countries [14,15].

Traders in the Cotebu market sell a higher number of different feedstuffs, except for corn bran, limestone, and molasses, compared to traders in other markets. This variation in the average quantity of the various main feedstuffs used in pig feed sold by traders in the various markets is largely due to the geographical location of the market and its position in relation to the nearby car parking. The Cotebu market’s proximity to the main car park, a popular destination for travelers heading to the country’s interior, makes it a preferred choice for herders seeking to minimize additional costs associated with loading and unloading. Upon examining the total quantity sold by each trader, it becomes evident that the quantity is relatively small, thereby supporting the notion that farmers do not own a large number of pigs.

By comparing the purchase price at which pig farmers buy molasses, cotton cake, and wheat bran between the different dates taken into account in this survey, we observe an increase in the purchase price on the day of the survey compared with other days. This is justified by the fact that these crops are seasonal in Burundi and that on the day of the survey, their harvest seasons were completed, in particular molasses, whose SOSUMO (Moso Sugar Society), which is the only company that produces sugar in Burundi, had already closed the season. The sale of these feedstuffs mirrors the trade of other products, where a decrease in quantity leads to an increase in price [16,17].

The average purchase price of certain feedstuffs from pig farmers is slightly lower than the average monthly selling price of these ingredients to different markets. This is because all the pig farms we surveyed are located around the town of Bujumbura, and their owners prefer to purchase all feedstuffs directly from nearby processing plants. Furthermore, we did not include the transport price of different feedstuffs because each farmer has a unique delivery method that varies from one pigsty to another and depends on the distance between the pigsty and the processing plant. The studied markets sell some feedstuffs, but the farmers interviewed do not purchase them. Farmers of other animals, particularly dairy cows and poultry, obtain supplies from these markets, which validates this observation. Given the number of pigs per farmer and their feed source, it is evident that all farmers manage a limited number of easily manageable pigs [18, 19].

All farmers use crop residues in the feeding of their pigs, which shows that this type of farming is still extensive and does not meet the standards required for pig farming. Moreover, the bromatological value of these crops is not manageable, and farmers use the purchased feedstuffs as feed supplements for pigs and not for basic feed. This is why not all farmers prefer to buy the mixed feedstuffs at the market or the outlet because of their high cost but prefer to buy them separately, and their use in pig feed vary from one pigsty to another. This behavior is similar to that of other farmers who engage in extensive pig farming systems in other countries [20-23].

The indifference of more than half of pig farmers in terms of profit gain can be explained by the fact that some farmers engage in pig farming without making financial calculations and others raise pigs with the aim of valuing their crop residues. After a long time, they notice that raising pork has not yielded the expected profit given the cost of buying the main feedstuffs and the cost of selling pork meat. Pig farmers are primarily concerned with lowering the price of various feedstuffs and raising the price of pork.

Conclusion

After looking at the list, the variability of feedstuffs available in the surveyed markets demonstrates sufficient potential to feed the pigs in the area under investigation. Trade in the main feedstuffs used in pig feed in Burundi follows the law of supply and demand. The selling price, sale frequency rate, and quantity sold differ from market to market, and due to its location, the Cotebu market appears to be more eventful compared to other markets. Despite limited resources, farmers buy different ingredients to feed their pigs in small quantities. Farmers, in the hope of making a profit from pig farming, have limited numbers that they can easily manage. They feed their pigs with readily available crop residues, and the various purchased feedstuffs are used as supplements. Despite the availability of several edible substances for pigs, we are even closer to a situation of a passion pig farm and far from a farm with a real commercial ambition.

References

- Manirakiza J, Hatungumukama G, Besbes B, Detilleux J (2020) Characteristics of smallholders’ goat production systems and effect of Boer crossbreeding on body measurements of goats in Burundi. Pastoralism 10: 2.

- Butore Joseph, Sindaye Daniel, Nimbona C, Kwizera A (2023) Determination of reproduction performance parameters of sows bred at the pig birth centers of Giheta, Nyabunyegeri and Mahwa in Burundi. Clin Res Anim Sci 3(1): 1-6.

- Kiki PS, Dahouda M, Toleba SS, Ahounou SG, Dotché IO, et al. (2018) Pig feed management and constraints of pig farming in South Benin. Rev of Breeding Veterinary Medicine of Trop Countries 71(1/2): 67-74.

- Djimènou D (2019) Genetic characterization and proposal for a genetic improvement program for local pigs raised in southern Benin 2017-2018.

- Alionye EBE, Ahaotu RO, Ihenacho, Chukwu AO (2020) Comparative evaluation of swine production with other domestic livestock in Mbaitolu local government area of Imo State, Nigeria. Sustain Agri, Food Environ Res 8: 212-234.

- Muhanguzi D, Lutwama V, Mwiine FN (2012) Factors that influence pig production in Central Uganda - Case study of Nangabo Sub-County, Wakiso district. Vet World 5(6): 346-351.

- Patience JF, Rossoni-Serão MC, Gutiérrez NA (2015) A review of feed efficiency in swine: Biology and application. J Anim Sci Biotechnol 6(1): 33.

- Ndagijimana V (2020) Analysis of effect of incorporating processed mucuna pruriens as source of protein and energy in home-mixed rations on performance of growing pigs and determination of optimal quantity. Université du Burundi Dépôt institutionnel official, pp. 1-82.

- Bacigale SBL, Nabahungu N, Okafor C, Manyawu GJ, Duncan A (2019) Assessment of livestock feed resources and potential feed options in the farming systems of Eastern DR Congo and Burundi. Int Livest Res Inst, pp. 1-32.

- Joseph B, Sindaye D, Nimbona C, Productions A, Hitimana M, et al. (2021) Bromatological analysis of the fodder marketed in the peri-urban areas of Bujumbura (Burundi): Towards spontaneous fodder conservation by transformation into silage. Advanced Studies in the 21st Century Animal Nutrition 86: 1-31.

- Makowski M, Piotrowski EW, Sładkowski J, Syska J (2017) Profit intensity and cases of non-compliance with the law of demand/supply. Phys A Stat Mech its Appl 473: 53-59.

- Borraz F, Zipitria L (2018) Law of one price, distance, and borders. SSRN Electron J, pp. 1-40.

- Yilmazkuday H (2021) Welfare implications of solving the distance puzzle: global evidence from the last two centuries. J Int Trade Econ Dev 30(4): 469-483.

- Dwijayani H (2019) Analysis of Effect of Price, Location and Services to Increase Sales Volume analysis of effect of price, location and services to increase sales volume Departement of Management, Faculty Economics of Universitas Darul ‘ Ulum, Jombang, Indonesia, C:1-4.

- Irfan A, Andi Nuryadin, Pahmi, Andi Alim (2023) The influence of location and price on shopping decisions at practical gelael makassar. J Econ Resour 6(1): 191-199.

- Minot N (2014) Food price volatility in sub-Saharan Africa: Has it really increased? Food Policy 45: 45-56.

- Paganelli MP (2022) Adam Smith’s Digression on Silver: The centrepiece of the Wealth of Nations. Cambridge J Econ 46(3): 531-544.

- Peden RSE, Akaichi F, Camerlink I, Boyle LA, Turner SP (2019) Pig farmers’ willingness to pay for management strategies to reduce aggression between pigs. PLoS One 14(11): e0224924.

- Delsart M, Pol F, Dufour B, Rose N, Fablet C (2020) Pig farming in alternative systems: Strengths and challenges in terms of animal welfare, biosecurity, animal health and pork safety. Agric 10(7): 1-34.

- Kabirizi JM, Zziwa E (2014) The role forages in pig production systems in Uganda. Int Cent Trop Agric, pp. 1-41.

- Mbuthia JM, Rewe TO, Kahi AK (2015) Evaluation of pig production practices, constraints and opportunities for improvement in smallholder production systems in Kenya. Trop Anim Health Prod 47(2): 369-376.

- Adesehinwa AOK, Boladuro BA, Dunmade AS, Idowu AB, Moreki JC, et al. (2024) Invited Review Pig production in Africa: current status, challenges, prospects and opportunities. Anim Biosci 37(4): 730-741.

- Dupon L, Trabucco B, Muñoz F, Casabianca F, Charrier F, et al. (2024) A combined methodological approach to characterize pig farming and its influence on the occurrence of interactions between wild boars and domestic pigs in Corsican micro-regions. Front Vet Sci 11: 1253060.

© 2024 Joseph Butore. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)