- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Technical & Scientific Research

Advancements in Moringa oleifera Use for Treatment of Water and Wastewater

Leslie G and Timothy JH*

Department of Chemistry and Physics, Southwestern Oklahoma State University, USA

*Corresponding author:Timothy J Hubin, Department of Chemistry and Physics, Southwestern Oklahoma State University, Weatherford, OK, 73096, USA

Submission: November 04, 2025:Published: December 05, 2025

Volume5 Issue5October 31, 2025

Abstract

Moringa oleifera, a versatile plant utilized across various domains, shows significant promise as a natural coagulant for water and wastewater treatment. This study reviews the advancements in employing M. oleifera to address the pressing global water contamination crisis, particularly in developing countries where access to clean water is critical. We analyze the effectiveness of M. oleifera in removing turbidity, harmful microorganisms, and contaminants such as heavy metals from diverse water sources. Characterization studies highlight its superior coagulation properties compared to traditional chemical coagulants, revealing a reduction in turbidity by up to 87% and substantial antibacterial activity. Additionally, the plant’s components can be enhanced with materials like sand for improved efficacy. Surveys conducted in rural communities show a gap in awareness regarding M. oleifera’s water purification potential, suggesting the need for educational outreach to promote its use. This review underscores the importance of integrating M. oleifera into water treatment strategies, advocating for its scalability and sourcing sustainability to combat waterborne diseases and improve public health outcomes globally. Continued research and innovation could further enhance its application, positioning M. oleifera as a costeffective and eco-friendly solution in the ongoing battle for safe drinking water.

Introduction

Water is one of the necessary basics of life. Contaminants in water can cause harm to all life. There has been an influx of organic, inorganic, and mineral materials entering the environment by way of natural events and human activity [1]. These contaminants have effects on human health and the environment that are more notable in developing countries, where access to wastewater treatment systems is not always available [2]. Almost 80% of diseases in developing countries are waterborne diseases. In children, unsafe water quality has shown it plays a key role in mortality of young children [3,4]. To solve this issue, developing cost-effective and sustainable water treatment technologies should be a priority. There has been a rising interest in using natural coagulants in place of synthetic coagulant agents. Numerous plant materials have been known as effective coagulant agents. One of the plant materials, Moringa oleifera, has shown great promise as coagulant and antimicrobial agents [5]. In fact, studies to determine the efficacy of M. oleifera started in the 1970s [6]. M. oleifera is available across the tropics for differing purposes. For example, M. oleifera has extensive uses in medicine, agriculture and industry [7]. All parts of the M. oleifera plant have a use. The M. oleifera seed has been characterized to have a water-soluble component, which makes it useful as a coagulant for water treatment in developing countries [8]. The main aim of the Chemical Reviews article, titled “Potential of M. oleifera for the Treatment of Water and Wastewater,” was to show an overview for the use of M. oleifera as a feasible method for water treatment. The article was able to show that M. oleifera is successful in removing metal ions, turbidity, organic and biological substances from water [9]. Scientists must continue to explore and expand the knowledge of M. oleifera as a coagulant to fulfill the potential of this plant as a cost-effective and sustainable method for water treatment.

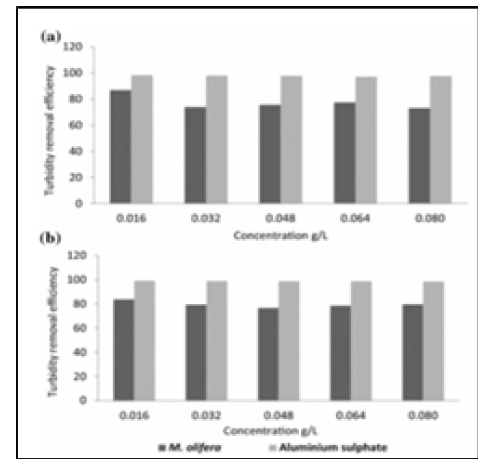

Characterization of M. oleifera effectiveness

As mentioned previously, it is estimated that up to 80% of all illness and disease is caused by poor sanitation and polluted or unavailable water. One study analyzed the water purifying and antibacterial efficacy of M. oleifera. To test these properties of M. oleifera, water samples were taken from two different rivers in Ethiopia. M. oleifera seed powder was extracted and samples were prepared for analysis. After conducting the jar test, supernatants were recovered for total coliform bacteria counts, pH studies, and turbidity measurements. To determine the total coliform bacteria, the Most Probably Number (MPN) test was used. A turbidimeter was used on the samples to determine turbidity. A pH meter was used to measure the pH before and after treatment. Agar well diffusion was used to determine susceptibility of organisms to the M. oleifera extract. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentrations (MBC) were determined using Mueller-Hinton agar. M. oleifera reduced water turbidity about 87% for water samples from the Angered River and about 84% for the Shinta River. Still, aluminum sulfate was able to reduce turbidity in these samples by 98% and 99%, respectively. Aluminum sulfate significantly decreased the pH of the samples, while M. oleifera did not significantly change the pH of the samples. Figure 1 shows the comparison between M. oleifera and aluminum sulfate during turbidity removal at varying concentrations. As for the coliform count, significant reduction of coliform bacteria counts was reported in both treated samples. MIC and MBC results showed that acetone extracts of M. oleifera have potential as antibacterial agents. Both rivers had pH levels within acceptable standard set by WHO. M. oleifera did not significantly affect pH, which was consistent with other studies.

Figure 1:The comparison between M. oleifera and aluminum sulfate during turbidity removal at varying concentrations.

The M. oleifera seeds are a low-cost alternative that will reduce development of ulcers. Although there was great turbidity reduction by M. oleifera, it was not enough to conform to the WHO standard for turbidity. Further investigation suggests that floating flocs could be removed from the samples to further reduce turbidity. Without altering the pH on purpose, M. oleifera was able to reduce turbidity at low concentrations. M. oleifera seed extracts showed antibacterial activity against four different bacteria. These findings suggest seed extracts could be used as a natural antibacterial agent for waterborne bacterial diseases. The results show the benefits of M. oleifera for areas that cannot obtain clean drinking water [10]. Increasing human population and lifestyles have influenced municipal wastewater quality. It has been estimated that 1.1 billion people do not have access to clean water. Most of these people reside in developing countries. The purpose of this study is to investigate using M. Oleifera (MO) biomass as a coagulation agent to remove turbidity, Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), and Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD). MO cake was obtained the extraction process of a MO seed. Wastewater samples were collected from a university sewer system in Nigeria and characterized.

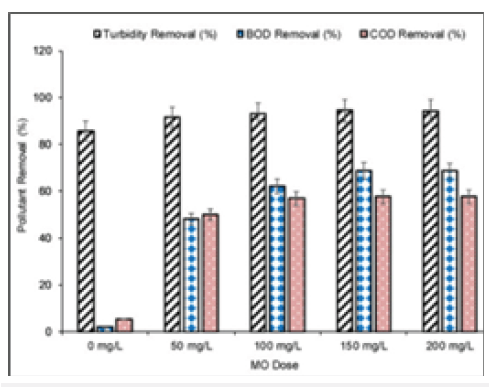

Figure 2:The effect of MO dose on the three parameters.

Using the Jar test set-up, the wastewater was examined for turbidity, BOD, and COD parameters. The removal efficiency equation was used to quantify the results. A simplified first-order kinetic equation was used to determine the rate of solute sorption occurred. Using the Gompertz equation, cumulative parameter removal efficiency was determined. Results show statistically significant difference in characteristics of municipal wastewater before and after MO biomass treatment. The effect of MO dose on the three parameters is shown in Figure 2. The results show that optimal turbidity removal was reached at a 150mg/L dose. The optimal BOD and COD removal was achieved at 150mg/L which followed the same trend as turbidity. The results from the first-order kinetics model indicated that the maximum removal of the three parameters was achieved by a 150 mg/L dose of MO. Lastly, the predicted and measured results were compared from the study to determine if the prediction modeling results were valid. The results shows that the model was able to simulate the removal of the three parameters from municipal wastewater using M. oleifera biomass. To conclude this study, MO biomass was found to be an effective coagulant for removal of pollutants from wastewater. There was significant reduction in turbidity, BOD and COD. Characteristics of wastewater can cause variation in results so additional studies should be conducted to ensure the level of water quality is appropriate [11].

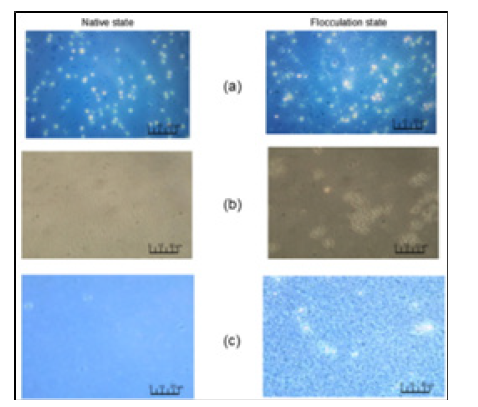

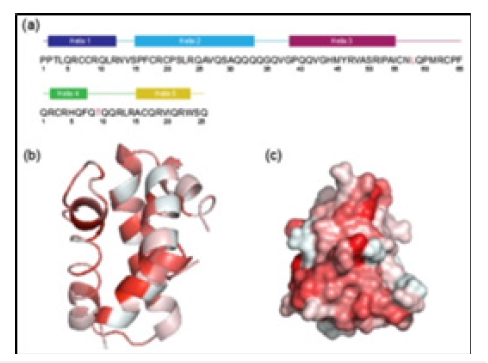

Next, the proteins from Moringa oleifera seeds were characterized by another study. One portion, labeled Mo-CBP3, was characterized at the molecular level. The protein from the M. oleifera seeds is the active coagulation agent. Understanding of why some seeds and certain proteins are better coagulation agents is important for future application. This study will determine the properties and behavior of the proteins from M. oleifera seeds. First the protein was extracted from the seeds and several analyses were performed. These techniques included bio-chemical and physical procedures like crystallization, X-ray diffraction, mass spectrometry, chromatography and neutron reflection. The results from ion exchange and size exclusion chromatography show the change of distribution of size for protein components. The difference could be a result of the proteins dependent interactions to salt. Mass spectrometry showed that the different size species were separated in the size exclusion chromatography. Flocculation activity was observed using light microscopy. Figure 3 shows the visible aggregation of particles in three environments. These results show that flocculating can occur in a variety of environments. Crystallization was carried out successfully for fraction D of the Mo-CBP3-4 protein. Figure 4 shows the helix and surface representations that were produced. Absorption to silica and alumina were also tested. The results from this study agreed with previous work that observe flocculation activity. The observations show that the M. oleifera seed proteins interaction for flocculation may depend on the specific proteins that are present.

Figure 3:The visible aggregation of particles in three environments. a) Aggregates for algae. b) Aggregates for bacteria.

Figure 4:The helix and surface representations that were produced.

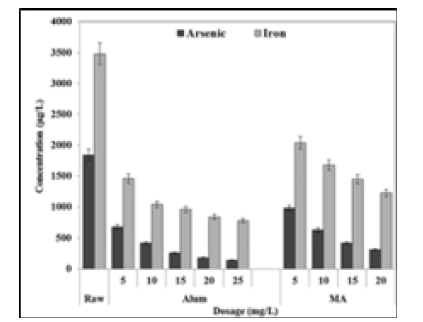

Neutron reflection shows the interaction between the protein and silica which demonstrates the potential binding mechanism. M. oleifera seed proteins as a flocculating agent may need a combination of different materials to enhance the overall use. This study shows the importance of characterized individual protein components as some may be more crucial for flocculation [12]. Heavy metals in water have been a concern because of their toxicity. Arsenic contaminated water entering the human body can affect their health. Removal of contaminates like arsenic are necessary to reduce the threat of health risks to the population. Natural coagulation is cost-effective, feasible and environmentally friendly. Coagulants include M. oleifera seeds, Biological Activated Carbon (BAC), Biological Aerated Filters (BAF), and alum coagulant. This study seeks to compare the removal of arsenic and iron using alum and BAC to M. oleifera and BAF treatment processes, respectively. Samples were collected and extracted. The chemical coagulant alum and the natural coagulant M. oleifera seeds were used to carry out coagulation experiments at different doses and pH conditions. BAF and BAC coagulation experiments used columns that operated in a downflow mode. Dissolved Organic Carbon (DOC) was removed from the columns and a Total Organic Carbon (TOC) analyzer was used to determine the concentration. The iron and arsenic concertation were determined by an atomic absorption spectrometry.

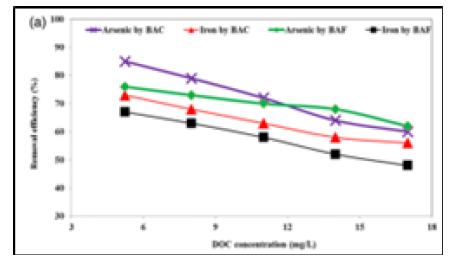

Figure 5 shows the absorption of arsenic and iron compared to the coagulation dose between alum and M. oleifera. Alum had higher efficiency removing arsenic and iron. Greater absorption of arsenic compared to iron could be attributed to molecular size. The effect of pH between pH range 4-6 was examined. As the pH decreased, arsenic removal increased. BAC and BAF were both efficient in reducing the iron contaminant, but BAF had a lower efficiently compared to BAC. Both were also effective in arsenic removal. The more contact BAC and BAF had, the more arsenic and ion reduction was observed. The presence of organic matter affected the levels of arsenic an iron removal. Increased DOC concentration lowered the removal of arsenic and iron from water. Figure 6 shows the effect of DOC on BAC coagulation to remove arsenic and iron. The World Health Organization (WHO) has an allowed limit of 10μg/L of arsenic in potable water. The combination of a coagulant and a biological process are necessary to meet the established limit for arsenic and iron concentrations. This study compared BAC, BAF, M. oleifera and alum for coagulation processes to remove arsenic and iron form potable water. Coagulation removed arsenic and iron form drinking water. Alum was better at removing these contaminants compared to M. oleifera. Removal of arsenic and iron depend on the coagulant dosage and pH. Overall, BAF, a new coagulant and a natural coagulant can reduce the amount of arsenic and iron present in drinking water [13].

Figure 5:The absorption of arsenic and iron compared to the coagulation dose between alum and M. oleifera.

Figure 6:The effect of DOC on BAC coagulation to remove arsenic and iron.

Industrial wastewater treatment of dye is a challenging problem. Some pollutants are resistant to established biological treatment approaches. These approaches are often reported to have consistency issues in the quality of treatment. Common treatment methods include removal techniques or destructive techniques. Removal techniques include coagulation, adsorption, and separation of membranes. Destructive techniques include biological processes, oxidation procedures and incineration. Coagulation is a physicochemical process. It acts to neutralization the charge of pollutants and removes them by a settling aggregate. Coagulation does produce a stream of secondary waste called sludge. The current techniques need more biological options that produce less secondary waste and improvement to meet the strict pollution control levels around the world. Newer biocoagulants, like the seeds of Azadirachta indica and the pads of Acanthocereus tetragonus are studied and compared to two known biocoagulants, Moringa oleifera and Cicer arietinum seeds. Since it is difficult to measure the aggregation of particles and particle size during the three stages of the coagulation process, the Focused Beam Reflectance Measurement (FBRM) was used to study aggregation kinetics.

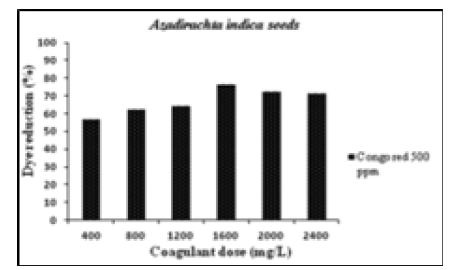

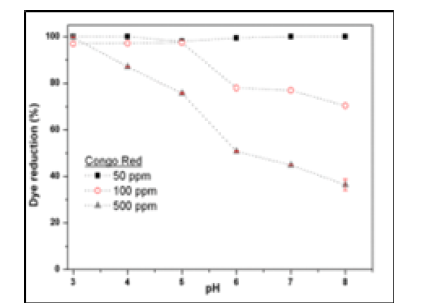

Each biocoagulant was prepared and extracted for evaluation and coagulation studies. The coagulation studies used synthetic wastewater containing the Congo Red dye. The optimal biocoagulant does which produced minimum sludge was determined by comparison of dye removal to varying doses of biocoagulants. The dye concentration was measured using a spectrophotometer at 498nm. The influence of pH was studied using a pH meter after finding the optimum dosage of biocoagulant. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) was used to analyze the biocoagulants and sludge. Determining the optimal coagulation dose is crucial to have the best performance during wastewater treatment. Figure 7 shows the behavior of A. indica. Almost 80% of the dye was removed and at a much lower dose compared to existing biocoagulants. For practical use, a coagulation aid may be necessary since the settling time for AI was high at ~72 hours. Similarly, C. arietinum had about 95% dye removal but had a settling time of 72 hours. The influence of pH is shown in Figure 8. The biocoagulants were found to be most effective in acidic pH around pH 3. As pH increases, the efficiency of the biocoagulant decreases. In addition, for M. oleifera, sludge volume index was lower than A. tetragonus.

Figure 7:The behavior of A. indica.

Figure 8:The influence of pH.

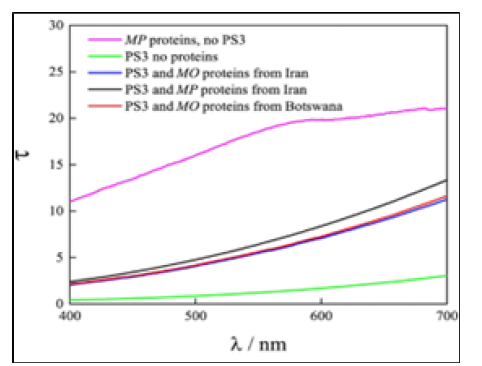

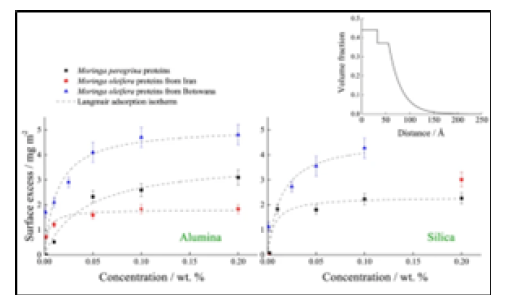

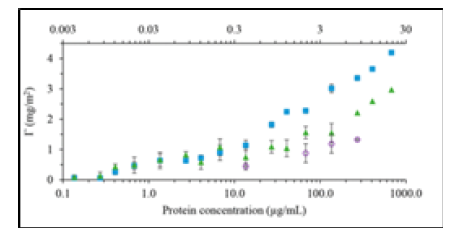

The SVI values show the advantage of using biocoagulants as opposed to conventional chemical coagulants since biocoagulants produce less sludge. This study showed that A. indica and A. tetragonus, new biocoagulants, and M. oleifera and C. arietinum, known biocoagulants, have great potential in dye wastewater treatment. Further research is necessary to reduce settling time, improve coagulation power present in the ingredients and to better understand the coagulation mechanism of the newer biocoagulants [14]. This study investigates the ability of proteins extracted from Moringa peregrina and Moringa Oleifera seeds to adsorb different materials. The results of this study are important in regions where clean water is hard to obtain. Three different types of surfaces with varying properties were used to study the adsorption of proteins. These surfaces were polystyrene colloidal particles, silica and alumina. M. peregrina and M. oleifera seeds were deshelled and crushed. The powder contained the protein. The protein was then purified. Flocculation was measured using UV transmission. Neutron reflectometry was used to determine the amount and structure of the adsorbed proteins. Flocculation was observed in samples with PS3 latex particles and M. peregrina and M. oleifera proteins. The results could be observed by the naked eye, but to make a quantitative comparison, UV results were graphed in Figure 9.

Figure 9:The results could be observed by the naked eye, but to make a quantitative comparison, UV results.

The neutron flection data in Figure 10 shows that M. oleifera from Botswana had higher adsorption on alumina and silica compared to the other two species. M. peregrina had higher absorbance to alumina than to silica. These results show which species can be more effective for aggregation in certain water conditions. In addition, M. peregrina proteins form denser layers on alumina compared to silica surfaces. M. oleifera from Iran had denser layers on silica compared to the alumina. The differences could be accounted for by the different compositions of the samples which may affect the ability to form layers. Lastly, there were notable differences in amino acid composition compared to other studies. These results may be due to region of where M. peregrina and M. oleifera were from or how the proteins were extracted and purified. These small changes could be the reason for the differences in adsorbed amount and structure for the proteins on the three different surfaces. These results show that M. oleifera proteins are efficient as flocculant agents in water purification. The purpose of this study was to see how M. peregrina compares since it is native to other regions and has been less exploited. The results show that M. peregrina can act as an effective flocculant agent and acts similarly to M. oleifera. This allows for regions with M. peregrina to aid in water purification [15].

Figure 10:The neutron flection data.

M. Oleifera in communities around the world

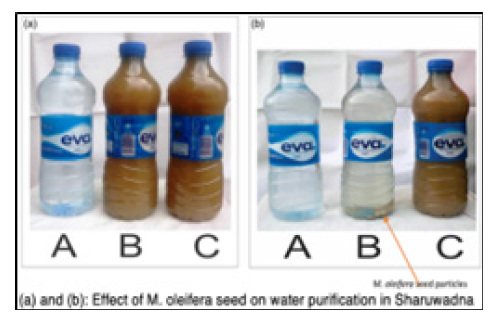

Diarrhea is the second leading cause of mortality in children worldwide. Risk factors of diarrhea include lack of access to sanitary water supply and poor personal hygiene. In low- and middle-class countries in sub-Saharan Africa, mortality rates from diarrhea are high. Although there has been increased knowledge about the efficacy of using Moringa oleifera, which is available in the area, for water purification, there has been no documentation of its use for Home-Based Water Treatment (HWT) or prevention of diarrhea in Nigeria. The aim of this study was to understand the attitudes towards the use of M. oleifera for HWT and prevention of diarrhea in Nigeria, which was ranked second among 15 countries to have the highest burden of diarrhea. The study design was qualitative and asked “what” and “why” questions regarding use of M. oleifera for HWT. The study was conducted in Nigeria where rural populations reside in areas that have limited access to health services and amenities. Thirteen participants were recruited. Of the 13 participants, 8 were community members, 2 were health implementers and 3 were policy makers. Eight were female. First, informed consent was needed from the participants. Data was collected using an interview guide. Community member interviews were recorded and translated. Health implementers and policy makers had interviews in English. Since there was lack of knowledge using M. oleifera from community members, a demonstration was done for water purification using M. oleifera seeds. Figure 11 shows visual representation shown to the community. Figure 11(a) shows Bottle A with commercially available bottled water. Bottle B and C are filled with water from their local river. One M. oleifera seed was added to bottle B and C was not treated. After three hours, we see the results in Figure 11(b). It shows that bottle is significantly clearer with M. oleifera seed particles settling to the bottom. The data from the sample participants was analyzed using thematic analysis. The results showed five themes: difficulty obtaining water, knowledge of unsafe water and diarrhea, knowledge of purification methods, knowledge of M. oleifera uses, implementation of policy.

Figure 11:Visual representation shown to the community. a) Bottle A with commercially available bottled water. Bottle B and C are filled with water from their local river. b) One M. oleifera seed was added to bottle B and C was not treated.

The communities get water from polluted rivers about 25- 30km from their location. Six of eight community members knew there was a link between dirty water and health. Most of the respondents knew at least one method to purify water, but it was a method used consistently due to the cost and time. Health implementers and policy makers thought that these communities were aware of other purification techniques, like boiling water. While these communities might have known, they did not know how to implement the knowledge. All participants had heard of M. oleifera, but none of them knew that the seeds could be used for water purification. No policy mentioned the use of M. oleifera seeds for HWT. Policy makers were willing to promote M. oleifera seeds for HWT after being provided information regarding their effectiveness. This study showed the possibility for M. oleifera seeds to be used for HWT since they are viable, cost effective and energy saving for rural Niger communities. It also highlights the need to provide information and health education in a consistent and accurate manner to all communities [16]. Since the 1990s, water pollution has worsened in almost all rivers across Africa, Latin America and Asia. Researchers have been pushed to develop new techniques to purify water. Moringa oleifera has already been known to serve as a natural coagulant for water purification, but M. oleifera has only recently been introduced in Tunisia and in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Research has not been conducted for the M. oleifera seed’s ability to treat wastewater in Tunisia. This study aims to test three varieties of M. oleifera found in Tunisia and their purification efficiency on urban wastewater.

First, it was necessary to characterize the three varieties of M. oleifera which were named Mornag, Egyptian and Indian varieties. Next, the wastewater samples were collected. There were two samples used in this study, Raw Urban Wastewater (RUW) and Treated Urban Wastewater (TUW). The seeds were then processed and added to each wastewater sample at increasing concentrations. The wastewater before and after treatment were characterized following certain parameters. Statistical analysis was performed on three aspects of the study, wastewater quality, M. oleifera variety and coagulant concentration. The physicochemical characteristics of RUW and TUW before and after treatment with M. oleifera varieties were documented. The two treatments were studied within pH range of 6.5-8.5 which is the recommended range for optimum coagulation. Electrical conductivity was reduced with treatment from M. oleifera in RUW and TUW. Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) levels are indicative of industrial pollution. All three M. oleifera varieties showed efficient removal of COD in both types of water samples. Analysis showed that Total Suspended Solids (TSS) influences treatment efficiency. RUW had high TSS which was reduced by the M. oleifera varieties, but the wastewater did not reach standards for agricultural use. Total Kjeldahl Nitrogen (TKN) contents varied among the three varieties. Further investigation would be needed. Metallic Trace Elements (MTE) the Egyptian variety treated wastewater that met started for agricultural use in RUW and TUW.

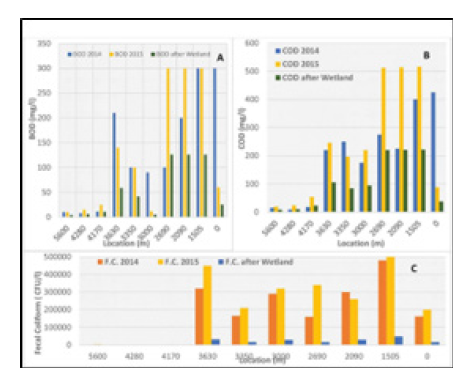

The treatment of M. oleifera varieties on RUW and TUW reduced contaminants efficiently. It was determined that the quality of the wastewater impacts on water treatment. M. oleifera varieties significantly influenced treatment outcome. The Egyptian variety had the best reduction of EC and TSS in both RUW and TUW. To conclude, M. oleifera can be used in urban wastewater treatment for irrigation [17].Low-cost and natural wastewater treatments are important for developing countries. This study compares and proposes wastewater treatment processes using wetlands, weirs and Moringa oleifera. Several studies were used to analyze wetlands as natural treatment processes. Additional studies investigated aeration by a weir. Lastly, laboratory studies examine M. oleifera seeds in treatment of drainage water. First, study areas were identified in Egypt. A wetland hydraulic system was designed. The criteria for the design include hydraulic load rate, detention time, density of plants, and the concentration at the entrance. The optimal design should have minimum retention time, water surface elevation and minimum cost. Figure 12 shows the water quality concentrations before and after using wetland water treatment. The measurements show that there was removal of suspended solids, BOD, COD, and fecal coliform. Treatment efficacy for M. oleifera and Nile water samples were observed. It was determined that M. oleifera seeds decrease pH with increasing concentration. Inverse relationships between electrocoagulation and M. oleifera seed powder. As M. oleifera dose increased, total dissolved solids decreased. All these findings were consistent with previous studies. For raw water, the results indicate that M. oleifera seeds are effective coagulation agents for water purification. Treatment using weirs showed decrease in pollution agents and high precents for removal of them. In conclusion, the results showed instream wetlands did reduce water contamination, but a more optimal design is needed to be suitable for rural communities. M. oleifera and weir structures both reduce pollutants in the water. These methods offer a costeffective alternative for rural communities [18].

Figure 12:The water quality concentrations before and after using wetland water treatment.

Enhancement of M. oleifera with different materials

Figure 13:The adsorption for all water-soluble proteins and cationic proteins, both having fatty acids removed.

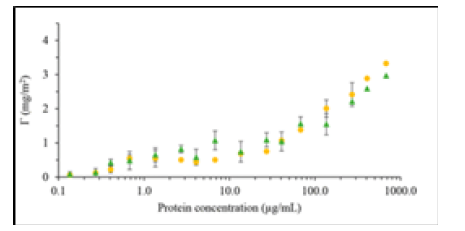

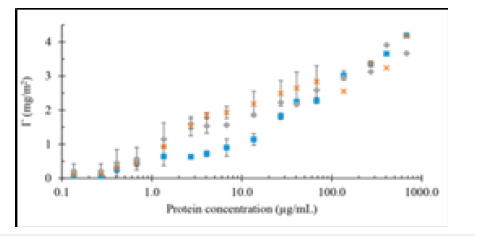

Drinking water is scarce in many developing countries. Modifications to Moringa oleifera-treated water is of great interest for these nations to have access to safe drinking water. M. oleifera cationic proteins can be adsorbed to sand granules that produce “f-sand” which is the protein-functionalized sand granules. F-sand has the potential to safe drinking water. Studies show that f-sand can reduce water hardness and algal blooms. This study wants to determine the impact of varying M. oleifera extract purification levels on adsorption to silica which is the main component in sand. Additionally, this study determined the impact of varying water conditions on f-sand performance. First, extraction of M. oleifera seed protein were obtained. Some samples removed fatty acids and other samples did not remove fatty acids. The samples were then used to prepare water-soluble proteins in varying water conditions. From the total protein extracts, cationic protein samples were prepared using preparative chromatography with a Waters Alliance Separations Module HPLC system. Silicon wafers were used during adsorption procedures using ellipsometry. Ellipsometry was used to determine film thickness of the excess protein concentration adsorbed to the wafers. The silicon wafers were placed in deionized water and a multiangle scan confirmed the layer thickness. Then the wafers were placed in the desired protein solutions and scans were taken continuously after. Layer thickness was calculated. Protein desorption experiments were performed and multiangle scans were recorded. Readsorption experiments were conducted to see if the protein would readsorb to the surface. Figure 13 shows the adsorption for all water-soluble proteins and cationic proteins, both having fatty acids removed. At concentrations 7μg/ml and below all protein samples are indistinguishable. At 14μg/ml and above, all water-soluble protein samples had high excess surface concentrations compared to cationic proteins.

Ellipsometry results show that there is no significant impact from noncationic protein adsorption. Figure 14 shows the adsorption for cationic proteins with and without fatty acids. It shows that there was no significant impact on adsorption of cationic proteins based on fatty acid presence or removal. Figure 15 shows the adsorption of all water-soluble proteins with fatty acids in varying water conditions. The conditions included deionized water, soft freshwater, and hard freshwater. Soft and hard water had similar adsorption, but differed form deionized water. Deionized water had lower surface excess concentrations than soft and hard water. The results show that adsorbed proteins would be limited in soft and hard water. Additionally, protein desorption was tested and gave rise to a simple scheme to remove proteins from f-sand to regenerate f-sand over and over. In conclusion, adsorption was greater for all water-soluble proteins on silica. No significant difference was noted by fatty acid presence or absence. Water hardness does influence the amount of adsorption [19]. Seed powder of Moringa oleifera is used for the coagulation of impurities from wastewater. Previous findings from the same lab showed that Moringa oleifera does remove heavy metal ions and dyes.

Figure 14:The adsorption of cationic proteins with and without fatty acids.

Figure 15:The adsorption of all water-soluble proteins with fatty acids in varying water conditions.

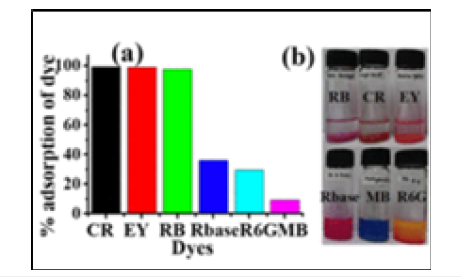

This study provides a reusable and sustainable lead to purifying water. While there are other studies demonstrating the removal of pollutants from water, not many look at the use of protein-based material to purify water. To do this, inorganic-protein nanoflower systems (CuPNF_MOCP) are prepared from the coagulant protein of Moringa oleifera and Cu2+ salt in phosphate buffer saline. These nanoflowers have high stability, better enzymatic activity, and sensing. Nanoflower morphology was studied using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM). Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (STEM) was used for mapping. Particle size analysis, thermal analysis and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy were conducted. Spectral studies were conducted on the Moringa oleifera seed powder. The Moringa Oleifera Coagulant Protein (MOCP) was extracted a purified. Next, the copper phosphate Moringa oleifera coagulant protein nanoflower was synthesized. The absorption and degradation of dye by CuPNF_MOCP was observed using UV-visible absorption analyses. Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICPAES) was used to study the absorption of heavy metal ions by CuPNF_MOCP. Figure 16 shows the results for Moringa oleifera seed powder that confirm that organic dyes were indeed absorbed. Next, it was determined that in the presence of Cu2+ salt and H2O2+2 the seed powder was able to completely decolorize the solution and solid. This data shows that organic dye can be oxidatively degraded. Additionally, using ICP-AES, the seed powder also demonstration absorption of toxic metal ions with the greatest affinity for Pb2+ ions. After isolating the MOCP, characterization data was collected using MALDI, UV absorption, fluorescence emission and CD. The results agreed with reported findings in the literature. Next, CuPNF_MOCP was prepared and elemental mapping confirmed the copper and phosphorus presence. Tighter petal packing is a result form higher protein concentration. Characterization of CuPNF_MOCP confirm the presence of the MOCP protein and copper phosphate in the nanoflower.

Figure 16:The results for Moringa oleifera seed powder that confirm that organic dyes were indeed absorbed.

The absorption of dyes by CuPNF_MOCP0.1 was efficient. Within 5 minutes, almost all the dye was absorbed. This shows that the water was freed form the dyes, but this is only true for the anionic dyes. Cationic dyes are not absorbed efficiently. Several cycles of dye degradation proved the reusability of CuPNF_MOCP0.1 since the NF acts efficiently in the degradation of dye as a catalyst under H2O2+2. Further tests show the efficiency of heavy metal ion absorbance and removal of Pb2+ ions from varying water samples. The results of this study support the properties of Moringa oleifera seed powder for the absorption and degradation of dye and absorption of heavy metals like lead. CuPNF_MOCP showed efficient absorption of dyes and high absorption of lead. The NF was reusable up to 10 cycles of degradation of dye and did not lose its activity [20]. M. Oleifera Seeds (MOS) have proven to be effective coagulants for water treatment. To achieve a lost-cost purification mechanism, MOS with aid of sponge was proposed. Sponge could prolong contact time between M. oleifera seed coagulant and pollutants. Sponge also acts as a natural filter. Sponge has a long-life span and is light weight. This study aimed to see how efficient MOS coagulant was at different doses, pH, and with or without the aid of sponge. First, raw materials like water and sponge were characterized using the Spectrophotometer Evolution 300BB. pH was measured using a pH meter. M. oleifera seed coagulant was prepared into a solution. Coagulation experiments were performed with and without the presence of sponges at varying conditions. Experiments were conducted to compare dosage amount of MOS coagulant and the effect on water treatment with and without the presence of sponges. The results showed that MOS coagulant decreased in efficiency without a sponge at 50mg/L. Sponge aid showed better efficiency [21].

At 15mg/L, turbidity decreased from 107 to 1.4NTU which is closer to the Egyptian standards for drinking water of 1.0NTU. This result can be explained by voids present in sponges that allow them to act as microfilters. This characteristic allows for prolonged contact between MOS coagulant and Natural Organic Matter (NOM). The results showed that sponge supplementation resulted in higher efficiency of the coagulation process. After the optimum dosage was established with and without sponges, pH studies were conducted. The results show turbidity reduction was greatest at pH 8. The reduction was even greater with sponge aid. Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM), the study investigated the most ideal conditions for MOS coagulant and sponge aid for different doses, pH, contact time needed in a treatment system. The results showed that linear doses of MOS play a role in removal of turbidity efficiency. This study concluded that MOS coagulant has proven to be an effective coagulant for water purification. Sponge supplementation results in greater efficiency of the coagulation process. Based on their results, sponges could be seen as additional filtration during the coagulation process. RSM determined optimum conditions for high efficiency of the process. These conditions were 250mg/L for the dose, pH of 6.15, and 12.78 minutes to obtain turbidity levels of 1.0 NTU that align with Egyptian standards for potable water.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this review has demonstrated the potential of Moringa oleifera as a viable solution for enhancing water and wastewater treatment, thereby reinforcing its significance in addressing global water quality challenges. Overall, M. oleifera has proven to be a valuable material for water and wastewater treatment. Studies continue to prove that every part of the M. oleifera plant, whether it be M. oleifera as a biomass or the proteins within it, is useful in treatment technologies. New studies have shown the enhancement of M. oleifera when combined with other materials. Continuing to use natural materials in combination with M. oleifera could lead to the development of cost-effective and sustainable water treatment technologies. A major goal going forward would be to consider how to upscale the use of M. oleifera to make these treatment technologies available to all.

References

- UNWWAP (2003) Water for people, water for life: The United Nations world water development report.

- Montgomery M, Elimelech M (2007) Water and sanitation in developing countries: Including health in the equation. Environ Sci Technol 41(1): 17-24.

- OECD (2006) Improving water management: Recent OECD experience.

- Guilbert JJ (2003) The world health report 2002: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life. Educ Health 16(2): 230.

- Abaliwano JK, Ghebremichael KA, Amy GL (2008) Application of the purified moringa oleifera coagulant for surface water treatment. WaterMill Working Paper Series 5: 1-22.

- Beth D (2005) Moringa water treatment. ECHO Community, p. 52.

- Rajangam J, Manavalan RSA, Thangaraj T, Vijayakumar A, Muthukrishan N (2001) Status of production and utilization of moringa in southern India. An Annotated Bibliography of Indian Medicine, p. 95451.

- Ndabigengesere A, Narasiah KS, Talbot BG (1995) Active agents and mechanism of coagulation of turbid waters using moringa oleifera. Water Res 29(2): 703.

- Sushil K, Amit K (2014) Potential of oleifera for the treatment of water and wastewater. Chemical Reviews 114: 4993-5010.

- Delelegn A, Sahile S, Husen A (2018) Water purification and antibacterial efficacy of moringa oleifera Agric & Food Secur 7: 25.

- Adelodun B, Ogunshina MS, Ajibade FO, Abdulkadir TS, Bakare HO, et al. (2020) Kinetic and prediction modeling studies of organic pollutants removal from municipal wastewater using moringa oleifera biomass as a coagulant. Water 12: 2052.

- Moulin M, Mossou E, Signor L, Kieffer JS, Kwaambwa H, et al. (2019) Towards a molecular understanding of the water purification properties of Moringa seed proteins. J Colloid and Interface Sci 554(15): 296-304.

- Pramanik BK, Pramanik SK, Suja F (2016) Removal of arsenic and iron removal from drinking water using coagulation and biological treatment. J Water Health 14(1): 90-96.

- Chethana M, Sorokhaibam LG, Bhandari VM, Raja S, Ranade VV (2016) Green approach to dye wastewater treatment using biocoagulants. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 4: 2495-2507.

- Nouhi S, Kwaambwa HM, Gutfreund P, Adrian RR (2019) Comparative study of flocculation and adsorption behavior of water treatment proteins from Moringa peregrina and Moringa oleifera Sci Rep 9(1): 17945.

- Aduro A, Ebenso B (2019) Qualitative exploration of local knowledge, attitudes and use of Moringa oleifera seeds for home-based water purification and diarrhea prevention in Niger State, Nigeria. Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development 9(2): 300-308.

- Marzougui N, Guasmi F, Dhouioui S, Bouhlel M, Hachicha M, et al. (2021) Efficiency of different moringa oleifera (lam.) varieties as natural coagulants for urban wastewater treatment. Sustainability 13(23): 13500.

- El Gohary R (2020) Low-cost natural wastewater treatment technologies in rural communities using instream Wetland, Moringa Oleifera, and aeration weirs: A comparative study. Cogent Engineering 7(1): 1846244.

- Nordmark B, Bechtel T, Riley J, Velegol D, Velegol S, et al. (2018) Moringa oleifera seed protein adsorption to silica: Effects of water hardness, fractionation, and fatty acid extraction. Langmuir 34(16): 4852-4860.

- Polepalli S, Rao CP (2018) Drum stick seed powder as smart material for water purification: Role of moringa oleifera coagulant protein-coated copper phosphate nanoflowers for the removal of heavy toxic metal ions and oxidative degradation of dyes from water. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 6: 15634-15643.

- Farghaly A, Abd Hamied EM, Gad AAM (2021) Sponge-mediated moringa oleifera seeds as a natural coagulant in surface water treatment. Journal of Engineering Sciences 49: 597-619.

© 2025 Kazeem Fasoye. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)