- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Technical & Scientific Research

Sustainable Development through Agroforestry: Proof from Rural Livelihood and Practices among Farmers in North Western, Nigeria

Salami KD1*, Gidado HA1, Lawal AA1, Oluakin M1, Uchenna PQ2, Jibo AU1, Muhammad YK1, Ilu KJ1 and Adeniyi KA3

1 Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management, Federal University Dutse, Nigeria

2 Department of Geography and Environmental Sustainability, University of Nigeria, Nigeria

3 Department of Animal and Environmental Biology, Federal University Dutse, Nigeria

*Corresponding author:Salami KD, Department of Forestry and Wildlife Management, Federal University Dutse, Jigawa State, Nigeria

Submission: August 26, 2025:Published: December 05, 2025

Volume5 Issue5December 05, 2025

Abstract

The agricultural sector in Jigawa State faces numerous challenges, including low productivity, environmental degradation, and widespread poverty, which hinder sustainable development and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This study employed utilizing questionnaires, interviews, and analysis of results to collect and analyze data. The target population consisted of practicing farmers in Dutse Local Government, with a sample size of 100 farmers selected from five communities. Data analysis employed descriptive and simple statistics, including frequencies, mean, and percentage, to analyze the data. The study reveals that 100% of the respondents are married males, with 36% being civil servants and 28% arable crop farmers. The primary drivers of agroforestry practices are income generation (40%), poverty alleviation (24%), and employment opportunities (22%). The benefits of agroforestry include income generation (40%), poverty alleviation (24%), and employment opportunities (22%). Findings shows that farmers generate substantial income from agroforestry, with 40% earning ₦500,000-₦600,000 and 25% earning ₦700,000 and above annually. The study highlights the need for targeted interventions addressing financial access, infrastructure development, and security enhancements to support agricultural growth. This study examines agroforestry practices among farmers, revealing economic motivations, benefits, and challenges, and highlighting the need for targeted interventions to support agricultural growth, farmer resilience, and sustainable development.

Keywords:Agroforestry practices; Dutse; Socio demographic; Sustainable development, Rural farmers

Introduction

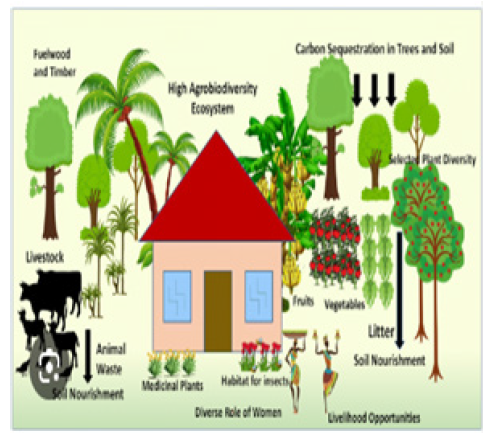

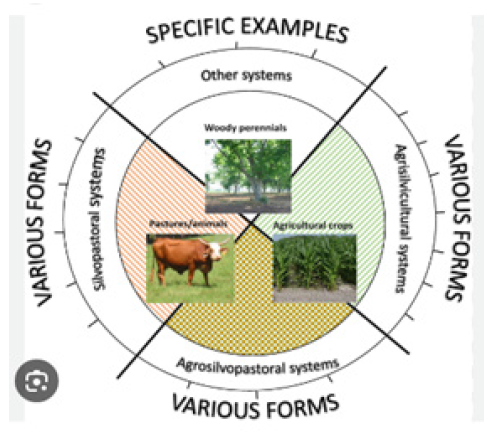

Agroforestry, a farming practice integrating trees into agricultural landscapes, has gained prominence globally as a sustainable development strategy, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) where agricultural productivity and environmental degradation are pressing concerns [1-3]. Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, faces significant agricultural and environmental challenges, including deforestation, soil degradation, and poverty [4,5]. The country’s agricultural sector, dominated by smallholder farmers, accounts for approximately 25% of GDP and employs over 70% of the workforce [6]. Jigawa State, located in Nigeria’s semi-arid region (Figure 1), is characterized by low agricultural productivity, limited access to credit and markets, and vulnerability to climate change [7]. Dutse, the state capital, is a hub for agricultural activities, with farmers engaging in various practices, including agroforestry [8]. Research has shown that agroforestry can enhance agricultural productivity, improve livelihoods, and promote environmental sustainability [9]. However, the adoption and effectiveness of agroforestry practices are influenced by sociodemographic factors, including age, education, and occupation [10]. Understanding these factors is crucial for designing targeted interventions and policies supporting agroforestry adoption and sustainable development in Nigeria Amare and Darr, 2024 (Figure 2).

Figure 1:Homegarden agroforestry systems.

Figure 2:Agroforestry system.

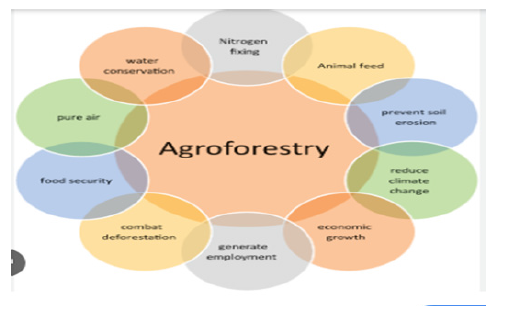

Previous studies have highlighted the significance of agroforestry in improving farmers’ livelihoods, particularly in rural areas [2]. For instance, a study in Kenya found that agroforestry practices increased farmers’ incomes by 30% and reduced poverty by 25% [11]. Similarly, research in Nigeria showed that agroforestry improved agricultural productivity and reduced soil erosion [12]. Despite these benefits, agroforestry adoption remains low in Nigeria, particularly in Jigawa State, due to limited access to information, credit, and markets. Nigeria’s agricultural sector, particularly in Jigawa State, faces numerous challenges that hinder sustainable development, including low agricultural productivity, environmental degradation, and widespread poverty. Despite its potential, agroforestry, a farming practice integrating trees into agricultural landscapes, remains underutilized in the region. This study aims to investigate the socio-demographic characteristics and agroforestry practices among farmers in Dutse, Jigawa State, Nigeria, providing valuable insights for sustainable development initiatives. By examining the relationships between socio-demographic factors, agroforestry practices, and sustainable development outcomes, this study will contribute to the existing body of knowledge on agroforestry and inform policy decisions and interventions aimed at promoting sustainable agriculture and improving livelihoods in Nigeria (Figure 3).

Figure 3:Achieving the sustainable development goals [31].

Methodology

Description of the study area

The study was carried out in Dutse Local Government, Jigawa state. The climate is a local dry grass plains climate. Its latitudes fall between 11.00 °N to 13.00 °N and longitudes 8.00 °E to 10.15 °E. There is little rainfall throughout the year. The average annual temperature is 26.5°C. About 743mm of precipitation falls annually according to the Köppen [13]. Jibo [14] revealed that it covered by Sudan savanna (Figure 4), also characterized by hot wet summer and cool dry winter with average raining season of 3-5 months (644mm) as it reported by Salami & Lawal [15]. The inhabitants are predominantly farmers engage in farming and rearing of livestock. Dutse is predominantly occupied by Hausa and Fulani with an estimated population of 153,000 [16]. The topography is characterized by high land area which is almost 750m. Soil tends to be fertile ranging from sandy-loam [17].

Data collection and sampling

Questionnaire was administered to the people living in the area based on the sampling technique of this study which is purposive sampling. The design of the questions was in form of closed-ended and open-ended. This involves methods which the researcher applied in collection, presentation, and analysis of data, Sample size and sampling techniques. The researcher employed a survey method of data collection and analysis. This involved a questionnaire survey, Interview and analysis of results. The target population comprises only practicing farmer of Dutse Local Government. There are five (5) communities in the local government which include Madobi, Warwade, Baranda, Laraba and Sabalari. 20 sample selected from each locality sample of this study.

Method of data analysis

Data collected analyzed by use of descriptive and simple statistics to recapitulate the questionnaire administered and during the fieldwork in a tabular form, frequencies, mean and percentage used to analyzed the data gathered.

Result

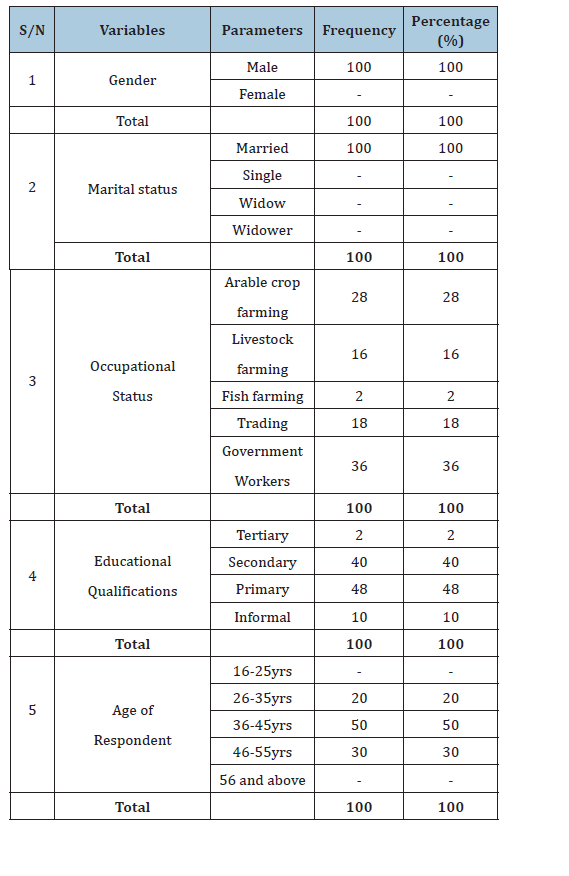

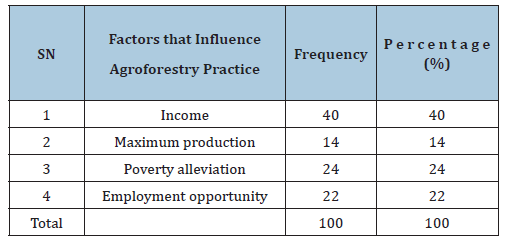

The demographic profile of the respondents, as presented in Table 1, reveals a homogeneous sample comprising 100% males, all of whom are married. Professionally, the respondents are distributed across various occupations, with 36% engaged as civil servants, followed by 28% as arable crop farmers, 16% as livestock farmers, and a minimal 2% as fishermen. An examination of their educational qualifications indicates that 48% of the respondents have primary school education, while 40% have secondary school education. Furthermore, 10% of the farmers have participated in informal education programs, and a mere 2% have pursued tertiary education. The age distribution of the farmers shows a clear concentration in the middle-aged bracket, with 50% falling within the 36-45 years range, 30% between 46-55 years, and the remaining 20% between 26-35 years. This suggests that the majority of the farmers are experienced and established in their professions, with a significant proportion having attained a moderate level of education. The prevalence of civil servants and arable crop farmers among the respondents underscores the importance of these sectors in the local economy. Overall, these findings provide valuable insights into the socio demographic characteristics of the farmers, which can inform policy decisions and interventions aimed at enhancing their livelihoods and productivity. The findings presented in Table 2 reveal that the primary drivers of agroforestry practices are predominantly economically motivated. Specifically, income generation emerges as the leading factor, influencing 40% of the respondents’ decisions to adopt agroforestry.

Table 1:Demographic characteristic of the respondents.

Table 2:Factors that influence agroforestry practice.

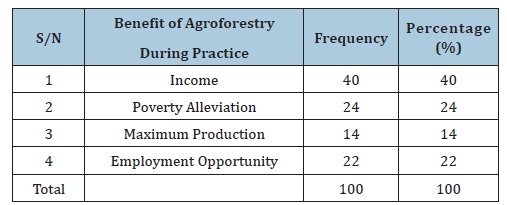

Poverty alleviation and employment opportunities follow closely, accounting for 24% and 22% of the respondents’ motivations, respectively. Notably, the pursuit of maximum production is the least influential factor, driving only 14% of the respondents’ decisions. These results suggest that agroforestry is perceived as a vital means of improving livelihoods and economic stability, rather than solely as a productivity-enhancing strategy. The emphasis on income generation and poverty alleviation underscores the importance of agroforestry in addressing socio-economic challenges. By understanding these motivations, policymakers and stakeholders can tailor interventions to support and enhance the adoption of agroforestry practices, ultimately contributing to sustainable development and improved well-being for local communities. The benefits of agroforestry practices to farmers are multifaceted, with economic gains being the most significant advantage. As shown in Table 3, income generation tops the list, benefiting 40% of the farmers. Poverty alleviation and employment opportunities closely follow, with 24% and 22% of the farmers citing these as key benefits, respectively. While maximum production is the least cited advantage, still, 14% of farmers recognize its importance.

These findings underscore agroforestry’s critical role in enhancing farmers’ livelihoods and economic resilience. By providing a stable source of income, alleviating poverty, and creating employment opportunities, agroforestry emerges as a vital strategy for sustainable development. Policymakers and stakeholders can leverage these insights to design targeted interventions supporting agroforestry adoption, ultimately improving the well-being of farming communities.

Table 3:Benefit of agroforestry during practice.

Table 4:Agroforestry practices among farmers.

Table 5:Challenges faced by farmers in practicing agroforestry.

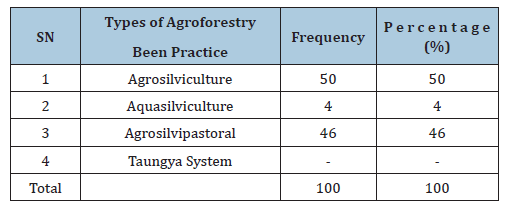

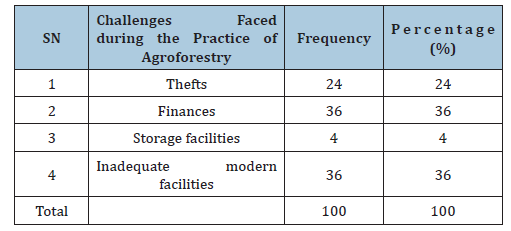

Table 4 reveals the predominant agroforestry practices among farmers, with a clear emphasis on integrating trees into agricultural landscapes. Agrosilviculture emerges as the most widely adopted practice, employed by 50% of the farmers, indicating a strong focus on combining trees with crops. Closely following is agrosilvopastoral, practiced by 46% of the farmers, which integrates trees, crops, and livestock. In contrast, aquasilviculture, which combines trees with aquatic resources, is the least practiced, accounting for only 4% of the farmers. These findings highlight the significance of treebased agroforestry systems in promoting ecological sustainability and livelihood enhancement. The prevalence of agrosilviculture and agrosilvopastoral practices underscores the potential for synergies between agriculture and forestry, supporting biodiversity conservation and climate resilience. Policymakers and stakeholders can prioritize support for these practices to enhance environmental benefits and farmer livelihoods. Table 5 highlights the significant challenges faced by farmers, with financial constraints and inadequate modern facilities emerging as the primary obstacles, each affecting 36% of the farmers. These interconnected issues hinder farmers’ ability to invest in essential equipment, technology, and infrastructure, ultimately impacting productivity and efficiency.

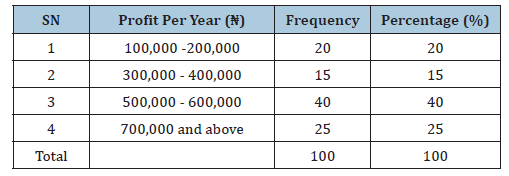

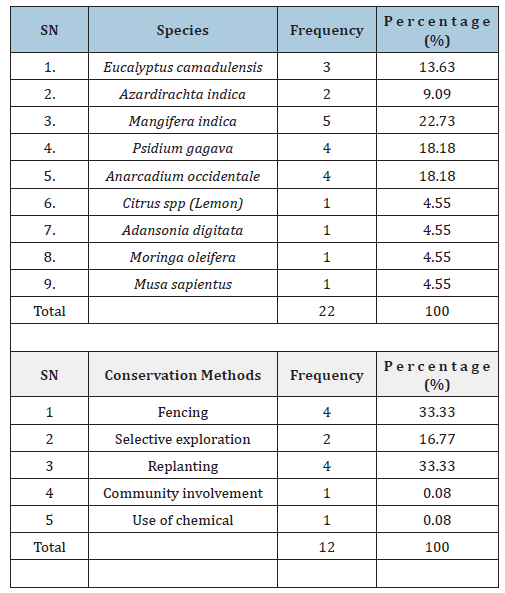

Theft is another notable challenge, affecting 24% of the farmers, emphasizing the need for improved security measures. In contrast, lack of storage facilities is the least cited challenge, affecting only 4% of the farmers. These findings underscore the critical need for targeted interventions addressing financial access, infrastructure development, and security enhancements to support agricultural growth and farmer resilience. The Table 6 presents below shows the distribution of profits per year among farmers in dutse, jigawa State. The results show that the majority of farmers (40%) earn between ₦500,000 to ₦600,000 per year, while 25% of farmers earn ₦700,000 and above. This suggests that a significant proportion of farmers are generating substantial income from their agricultural activities. On the other hand, 20% of farmers earn between ₦100,000 to ₦200,000 per year, indicating that some farmers are struggling to generate significant income. Overall, the Table 6 highlights the variability in income levels among farmers in the study area, with some farmers experiencing relatively high profits while others face challenges in generating income. The Table 7 presents a snapshot of the species composition of a particular ecosystem, with a total of 22 individuals representing 9 different species. The most dominant species is Mangifera indica, accounting for 22.73% of the total frequency, followed closely by Psidium spp and Anarcadium occidentale, both with 18.18% frequency. Eucalyptus camadulensis, Azardirachta indica, and Citrus spp (Lemon) are less abundant, with frequencies ranging from 4.55% to 13.63%. The remaining species, Adansonia digitata, Moringa oleifera, and Musa sapientus, are represented by a single individual each, contributing to the overall diversity of the ecosystem.

Table 6:Profit acquired per year.

The Table 7 suggests a relatively diverse ecosystem with a mix of native and possibly introduced species, highlighting the importance of conservation efforts to maintain this biodiversity. Furthermore, the dominance of certain species, such as Mangifera indica, may indicate a preference for specific environmental conditions or management practices, warranting further investigation. The Table 7 presents a snapshot of conservation methods employed in a particular area, with a total of 12 responses. The most commonly used methods are fencing and replanting, each accounting for 33.33% of the total frequency, suggesting a focus on physical protection and restoration of degraded areas. Selective exploration is also used, but to a lesser extent, with a frequency of 16.77%. In contrast, community involvement and the use of chemicals are rarely employed, with each accounting for only 0.08% of the total frequency. This suggests that conservation efforts may be largely driven by external actors, rather than being community-led, and that chemical-based methods are not a preferred approach. Overall, the Table 7 highlights the importance of physical conservation measures, such as fencing and replanting, in protecting and restoring degraded areas.

Table 7:Used Agroforestry plant species and conservation method.

Discussion

The demographic profile of the respondents in Table 1 reveals a homogeneous sample of 100% married males, consistent with previous studies highlighting the dominance of male farmers in agricultural sectors [4]. Professionally, the distribution across various occupations 36% civil servants, 28% arable crop farmers, 16% livestock farmers, and 2% fishermen mirrors the findings of Oladele [18], who noted the significance of agriculture and public service in rural economies. Educational qualifications show 48% with primary school education and 40% with secondary school education, aligning with UNESCO [19] reports on educational attainment in rural areas. The 10% participation in informal education programs and 2% pursuit of tertiary education echo the findings of Adebayo [12], highlighting the need for targeted education and training initiatives. The age distribution, concentrated in the 36-45 (50%) and 46-55 (30%) year ranges, suggests experienced and established farmers, consistent with the observations of Awotide [20].

This demographic profile underscores the importance of civil servants and arable crop farmers in the local economy, resonating with the work of Adesina [21]. These findings provide valuable insights into the socio demographic characteristics of farmers, informing policy decisions and interventions aimed at enhancing livelihoods and productivity [22]. Understanding these characteristics is crucial for effective agricultural development and poverty reduction strategies [23]. The primary drivers of agroforestry practices, as presented in Table 2, highlight the economic motivations of farmers, aligning with previous studies [3]. Income generation emerges as the leading factor (40%), followed by poverty alleviation (24%) and employment opportunities (22%), resonating with the findings of Kiptot [24]. The relatively low influence of maximum production (14%) suggests that agroforestry is valued for its socio-economic benefits rather than solely for productivity enhancement [9]. These results support the notion that agroforestry serves as a vital strategy for improving livelihoods and economic stability, particularly in rural areas [4]. The emphasis on income generation and poverty alleviation underscores agroforestry’s potential to address socioeconomic challenges, consistent with the sustainable development goals [25]. Research by Ajayi [2] and Mbow [26] similarly highlights agroforestry’s role in enhancing rural livelihoods and reducing poverty.

Understanding these motivations enables policymakers and stakeholders to design targeted interventions supporting agroforestry adoption, ultimately contributing to sustainable development and improved well-being for local communities [5]. Effective policy and extension services can enhance the economic benefits of agroforestry, encourage wider adoption and promote sustainable land management practices [23]. The benefits of agroforestry practices to farmers are multifaceted and far-reaching, with economic gains being the most significant advantage [3]. As shown in Table 3, income generation emerges as the primary benefit, benefiting 40% of the farmers, aligning with previous studies highlighting the economic benefits of agroforestry [27]. Poverty alleviation and employment opportunities closely follow, with 24% and 22% of the farmers citing these as key benefits, respectively, consistent with research emphasizing agroforestry’s role in reducing poverty and enhancing livelihoods [2,11]. Although maximum production is the least cited advantage (14%), it remains an important consideration for farmers seeking to optimize yields [9]. These findings underscore agroforestry’s critical role in enhancing farmers’ livelihoods and economic resilience, supporting the sustainable development goals [25]. By providing a stable source of income, alleviating poverty, and creating employment opportunities, agroforestry emerges as a vital strategy for sustainable development, echoing the conclusions of Mbow [26] & FAO [4]. Policymakers and stakeholders can leverage these insights to design targeted interventions supporting agroforestry adoption, ultimately improving the well-being of farming communities [5]. Effective policy and extension services can enhance the economic benefits of agroforestry, encourage wider adoption and promote sustainable land management practices [23].

Table 4 highlights the dominant agroforestry practices among farmers, with a pronounced emphasis on integrating trees into agricultural landscapes, aligning with previous studies [3]. Agrosilviculture emerges as the most widely adopted practice (50%), combining trees with crops, consistent with research emphasizing its ecological and economic benefits [2,9]. Agrosilvopastoral, practiced by 46% of farmers, integrates trees, crops, and livestock, supporting biodiversity conservation and climate resilience [11,26]. In contrast, aquasilviculture (4%) lags behind, underscoring the need for targeted support and research [4]. These findings underscore the significance of tree-based agroforestry systems in promoting ecological sustainability and livelihood enhancement, echoing the conclusions of IFAD [5]. The prevalence of agrosilviculture and agrosilvopastoral practices highlights potential synergies between agriculture and forestry, supporting biodiversity conservation and climate resilience [24]. Policymakers and stakeholders can prioritize support for these practices to enhance environmental benefits and farmer livelihoods, as advocated by World Bank [23]. Effective policy and extension services can promote widespread adoption of agrosilviculture and agrosilvopastoral, contributing to sustainable development and environmental stewardship.

Table 5 reveals the profound challenges confronting farmers, with financial constraints and inadequate modern facilities emerging as the primary obstacles, each affecting 36% of the farmers, resonating with previous studies [17,20]. These interconnected issues hinder farmers’ ability to invest in essential equipment, technology, and infrastructure, ultimately impacting productivity and efficiency, consistent with research highlighting the importance of financial access and infrastructure development [5,23]. Theft, affecting 24% of the farmers, underscores the need for improved security measures, echoing the findings of Kiptot [11] & Ajayi [2]. In contrast, lack of storage facilities, affecting only 4% of the farmers, suggests that storage infrastructure may not be a significant constraint, differing from the results of Sileshi [27]. These findings emphasize the critical need for targeted interventions addressing financial access, infrastructure development, and security enhancements to support agricultural growth and farmer resilience, aligning with the recommendations of FAO [10] & UN [25]. Effective policy and extension services can alleviate these challenges, promote agricultural productivity, and improve farmer livelihoods [23]. Table 6 presents a distribution of profits per year among farmers in Dutse, Jigawa State, revealing a varied income landscape, with 40% of farmers earning between ₦500,000 to ₦600,000 per year, and 25% earning ₦700,000 and above, indicating a substantial income generation from agricultural activities [2]. Conversely, 20% of farmers earn between ₦100,000 to ₦200,000 per year, suggesting that some farmers face challenges in generating significant income [18]. These findings are consistent with previous studies highlighting the importance of agriculture in generating income and improving livelihoods [5,23]. Furthermore, the results underscore the need for targeted interventions to support farmers, particularly those struggling to generate income, to enhance their productivity and economic resilience [4]. Overall, the Table 7 provides valuable insights into the income dynamics of farmers in the study area, emphasizing the need for sustainable agricultural development strategies to promote equitable income distribution and improved livelihoods.

The ecosystem assessed exhibits a relatively high level of biodiversity, with 9 species represented among 22 individuals, led by Mangifera indica (22.73%), Psidium spp (18.18%), and Anarcadium occidentale (18.18%) [28]. The dominance of certain species may indicate preferences for specific environmental conditions or management practices [29]. Conservation efforts, including physical protection and restoration, are crucial for maintaining biodiversity [30]. The use of fencing and replanting as primary conservation methods (33.33% each) suggests a focus on physical protection and restoration. In contrast, community involvement and chemicalbased methods are underutilized (0.08% each), indicating a need for more integrated and community-led conservation approaches [31]. Overall, the findings highlight the importance of physical conservation measures and community engagement in protecting and restoring degraded areas [32-35].

Conclusion

This study provides valuable insights into the socio demographic characteristics, motivations, benefits, and challenges of agroforestry practices among farmers. The demographic profile reveals a homogeneous sample of married males, predominantly engaged in civil service and arable crop farming, with moderate educational attainment [35-37]. Economic motivations drive agroforestry adoption, with income generation, poverty alleviation, and employment opportunities being the primary benefits. Agrosilviculture and agrosilvopastoral practices dominate, highlighting the significance of tree-based systems in promoting ecological sustainability and livelihood enhancement. However, financial constraints, inadequate modern facilities, and theft emerge as significant challenges. These findings underscore the need for targeted interventions addressing financial access, infrastructure development, and security enhancements to support agricultural growth and farmer resilience.

The study’s results align with previous research and international development goals, emphasizing agroforestry’s potential to address socio-economic challenges, promote biodiversity conservation, and enhance climate resilience. Policymakers and stakeholders can leverage these insights to design effective policies, extension services, and training initiatives that support agroforestry adoption, improve farmer livelihoods, and promote sustainable development. Prioritizing support for agrosilviculture and agrosilvopastoral practices can enhance environmental benefits and farmer livelihoods.

Moreover, addressing financial constraints, infrastructure development, and security concerns can alleviate challenges and promote agricultural productivity. The study contributes to the existing body of knowledge on agroforestry, highlighting its critical role in enhancing farmers’ livelihoods, economic resilience, and environmental sustainability. The findings inform policy decisions and interventions aimed at promoting sustainable agriculture, reducing poverty, and improving food security. Future research should focus on exploring innovative financing models, technology adoption, and climate-resilient agroforestry practices to further enhance the benefits of agroforestry for farming communities. Ultimately, this study underscores the importance of integrating agroforestry into agricultural landscapes, supporting biodiversity conservation, and promoting sustainable development. By addressing the challenges and leveraging the benefits of agroforestry, policymakers, stakeholders, and farming communities can work together to enhance livelihoods, promote environmental stewardship, and ensure a sustainable future for agriculture.

Recommendation

Based on the study’s findings, the following recommendations are made, Policymakers and stakeholders should prioritize support for agrosilviculture and agrosilvopastoral practices through targeted policies, extension services, and training initiatives. Financial access and infrastructure development should be addressed through innovative financing models and investments in modern facilities. Security concerns should be mitigated through community-based initiatives and law enforcement support. Additionally, research and development should focus on climate-resilient agroforestry practices, technology adoption, and market access enhancement. By implementing these recommendations, farming communities can enhance their livelihoods, promote environmental sustainability, and contribute to sustainable agricultural development. Effective implementation requires collaboration among stakeholders.

References

- Nazil A, Salami KD, Umar M, Alao YS (2025) Assessing the impact of agroforestry on sustainable livelihood in Langel village, Tofa local government area, kano state. Direct Research Journal of Agriculture and Food Science 13(3): 51-61.

- Ajayi OC, Akinnifesi FK, Sileshi G (2011) Economic analysis of agroforestry practices in Africa. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 35(4): 427-444.

- Mercer DE (2004) Adoption of agroforestry innovations in the tropics: A review. Agroforestry Systems 61(1): 15-28.

- FAO (2017) The state of food and agriculture 2017.

- IFAD (2016) Rural development report 2016.

- Salaam T (2017) National bureau of statistics and MOFP. 4: 29-118.

- Abubakar A, Magaji S, Ismail Y (2025) Bridging the adaptation gap: Barriers and opportunities for climate-resilient irrigation farming in dutse LGA, jigawa, Nigeria. International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies 52(2): 229-241.

- Vihi SK, Adedire O, Uma BK (2019) Adoption of agroforestry practices among farmers in gwaram local government area of jigawa state, Nigeria. Asian Journal of Research in Agriculture and Forestry 4(4): 1-13.

- Current D, Scherr SJ (1995) Benefits of agroforestry: An overview. Agroforestry Systems 30(1-2): 13-34.

- Marie Reine JKH, Ouinsavi CAN, Alaye EA, Wédjangnon AA (2025) Gendered trends and barriers in agroforestry adoption in Benin (West Africa). Discover Sustainability 6(1): 526.

- Kiptot E, Franzel S, Bodnar F (2016) Factors influencing adoption of agroforestry practices among smallholder farmers in Kenya. Journal of Agricultural Education 57(2): 136-148.

- Adebayo AA, Okorie A, Ogunjimi SI (2015) Analysis of farmers' characteristics and agricultural productivity in Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Science153(4): 751-762.

- Köppen G (2006) Climate classification, of dutse jigawa state, Nigeria. Department For international development (2012-05-04), called to be a midwife in northern Nigeria.

- Jibo AU, Salami KD, Inuha IM (2018) Effects of organic manure on growth performance of Azadirachta indica (Juss) seedlings during early growth in the Nursery. Fudma Journal of Sciences 2(4): 99-104.

- Salami KD, Lawal AA (2018) Tree species diversity and composition in the orchard of federal university dutse, jigawa. Journal of Forestry Research and Management 15(2): 112-122.

- Gidado HA, Salami KD, Kareem AA, Jibo AU, Fatima A, et al. (2023) Effect of frequencies of watering and water volumes on the growth performance of Adansonia digitata (Linn) seedlings. Australian Journal of Science and Technology 7(1):

- Salami KD, Ilu KJ, Odewale MA, Gidado AH, Umukoro SU (2019) Canopy structure of secondary forest in the federal university dutse, Jigawa state: Composition and importance of woody species. FUW Trends in Science & Technology Journal 4(2): 611-616.

- Oladele OI, Oladeji SO, Adewumi MO (2013) Analysis of agricultural households in Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural and Food Economics 1(1): 1-11.

- UNESCO (2019) Education for all 2000-2015.

- Awotide OD, Karimov AA, Kamruzzaman M (2015) Analysis of farmers characteristics and agricultural productivity in Nigeria. Journal of Agricultural Science 153(4): 751-762.

- Adesina AA, Coulibaly O (2014) Economic analysis of agricultural households in Nigeria. Journal of Development Studies 50(5): 761-775.

- Gollin D (2019) IFAD Research Series No. 34-Farm size and productivity: Lessons from recent literature. IFAD Research Series 34: 2018.

- World Bank Group (2018) Women, business and the law 2018.

- Kiptot E, Karuhanga M, Franzel S, Nzigamasabo PB (2016) Volunteer farmer-trainer motivations in East Africa: Practical implications for enhancing farmer-to-farmer extension. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 14(3): 339-356.

- UN (2015) Sustainable development goals.

- Mbow C, Smith P, Skole D (2014) Agroforestry solutions to address food security and climate change challenges in Africa. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 6: 104-114.

- Sileshi G, Akinnifesi FK, Ajayi OC (2014) Integrating agroforestry into agricultural landscapes: Benefits and challenges. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 38(4): 453-471.

- Tamang B (2018) Master degree in forestry.

- Purcell AT, Lamb RJ (1998) Preference and naturalness: An ecological approach. Landscape and urban planning 42(1): 57-66.

- Rawat U, Agarwal NK (2015) Biodiversity: Concept, threats and conservation. Environment Conservation Journal 16(3): 19-28.

- Berkes F (2007) Community-based conservation in a globalized world. Conservation Biology 104 (39): 15188-15193.

- Nair R, Madhavan S (2025) Vision 2030: SDG3 and Mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Journal of Sustainability 1(1).

- Ilu KJ, Salami KD, Gidado HA, Muhammad Y, Bello A (2020) Households responses to the roles of trees as wind breaker in dutse local government area of Jigawa State, Nigeria. Fudma Journal of Sciences 4(3): 162-16.

- Amare D, Darr D (2024) Holistic analysis of factors influencing the adoption of agroforestry to foster forest sector-based climate solutions. Forest Policy and Economics, 164: 103233.

- Berkes F (2007) Community-based conservation in a globalized world. Conservation Biology 104(39): 15188-15193.

- FAO (2019) Agroforestry for sustainable agriculture.

- Grime JP (1979) Plant strategies and vegetation processes. pp. 1-464.

© 2025 Kazeem Fasoye. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)