- Submissions

Full Text

COJ Biomedical Science & Research

Recent Progress in Advanced Wound Dressings for Wound Care: Materials and Treatment Technologies

Johyun Park, Jiwon Kang and Byoung Soo Kim*

Bio-Convergence R&D Division, Korea Institute of Ceramic Engineering & Technology (KICET), Republic of Korea

*Corresponding author:Byoung Soo Kim, Bio-Convergence R&D Division, Korea Institute of Ceramic Engineering & Technology (KICET), Republic of Korea

Submission: November 24, 2025; Published: December 12, 2025

Volume2 Issue4December 12, 2025

Abstract

Chronic and complex wounds remain a major clinical and socioeconomic burden, particularly in aging and diabetic populations. Modern wound dressings have gradually shifted from passive coverage to bioactive and device-integrated systems that actively modulate the wound microenvironment. Conventional moist dressings are typified by hydrocolloids, in which hydrophilic particles such as gelatin, pectin and carboxymethylcellulose are dispersed in an adhesive matrix usually supported by an occlusive polyurethane film. These dressings primarily provide passive treatment by absorbing exudate, maintaining a moist environment and relying on intrinsic self-healing capacity. In contrast, hydrogels are pre-hydrated three-dimensional networks that can conform closely to the wound bed, allow gas exchange and act as versatile carriers for bioactive molecules. Recent hydrogel systems have evolved into multifunctional platforms with adhesive, antibacterial, hemostatic, conductive and self-healing properties, often designed to deliver small molecules, growth factors or nanoparticles to address infection, oxidative stress and impaired angiogenesis. Hydrocolloids and other moist-retentive dressings are still widely used in clinical practice, but are increasingly complemented by Extracellular Matrix (ECM) based and decellularized scaffolds that better recapitulate native dermal architecture and provide bioactive cues for re-epithelialization. In parallel, drug-eluting dressings and nanoparticle-reinforced hydrogels offer spatiotemporally controlled therapy tailored to diabetic and pressure ulcers. Advanced treatment technologies such as negative pressure wound therapy and electroceutical or self-powered electrical dressings are being integrated with soft, conformable materials to deliver mechanical microdeformation, manage exudate and provide controlled micro-electrostimulation at the wound bed. Emerging smart dressings that combine sensing, data connectivity and on-demand actuation illustrate the convergence of biomaterials, drug delivery and bioelectronics toward integrated, intelligent wound care platforms.

Keywords:Wound dressing; Hydrogel; Hydrocolloid; Extracellular matrix; Decellularized matrix; Drugloaded dressing; Negative pressure wound therapy; Electrical stimulation; Smart dressing; Chronic wound

Abbreviations: ECM: Extracellular Matrix; DECM: Decellularized Extracellular Matrix; NPWT: Negative Pressure Wound Therapy; ES: Electrical Stimulation; ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; DFU: Diabetic Foot Ulcer; NP: Nanoparticle

Introduction

Optimal wound care aims to restore tissue integrity while minimizing infection, pain and scarring. Classical dry dressings such as gauze primarily provide mechanical protection and exudate absorption, but they do not actively support the coordinated stages of hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation and remodeling that underlie successful healing [1]. Modern moist wound healing concepts highlight the importance of maintaining a hydrated yet nonmacerating environment, allowing cell migration and matrix deposition while preventing desiccation and crust formation [1,2].

Over the past decade, a broad range of advanced dressings has been developed, including hydrogels, hydrocolloids, foams, alginates, ECM-based scaffolds and bioengineered skin substitutes [2-4]. In parallel, device-based modalities such as negative pressure wound therapy systems and electroceutical dressings have become integral to the management of complex wounds, particularly diabetic foot ulcers, pressure ulcers and burns z [1,5-9].

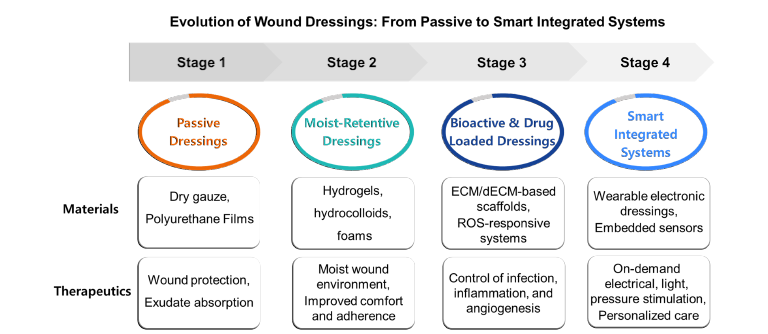

This mini-review focuses on two complementary dimensions of recent progress: (i) material platforms such as hydrogels, hydrocolloids, ECM-derived matrices and drug-loaded or stimuliresponsive dressings, and (ii) treatment technologies that use pressure or electrical cues to accelerate wound closure. Here, representative examples and key design principles are highlighted rather than an exhaustive catalog of available products. An overview of the evolution of wound dressings from passive coverings to smart integrated systems is schematically summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1:Schematic illustration of the evolution of wound dressings from passive to smart integrated systems. Stage 1 dressings (dry gauze, polyurethane films) provide basic wound protection and exudate absorption. Stage 2 moist-retentive dressings (hydrogels, hydrocolloids, foams) maintain a moist environment and improve comfort and adherence. Stage 3 bioactive and drug-loaded dressings (ECM/dECM-based scaffolds, ROS-responsive systems) enable localized control of infection, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Stage 4 smart integrated systems (wearable electronic dressings with embedded sensors) deliver on-demand electrical, light, and pressure stimulation to support personalized wound care.

Discussion

Hydrogels and hydrocolloids as moist-retentive dressings

Hydrogels are three-dimensional hydrophilic networks with high water content, oxygen permeability and excellent conformability, which makes them attractive as primary dressings for clean, low to moderately exudative wounds and burns [3,4,10]. Recent studies highlight a shift from “passive” hydrogels to functional systems that integrate antibacterial agents, hemostatic components, adhesive catechols, self-healing dynamic bonds and conductive elements for real-time monitoring or electrical stimulation [3,4,10-13]. These multifunctional hydrogels can scavenge ROS, modulate inflammation and promote angiogenesis, thereby addressing key barriers in chronic wound healing [10-13].

In addition, bioadhesive hydrogel systems that combine strong tissue adhesion with improved water retention have attracted increasing attention. Crosslinker-free poly (2-hydroxyethyl acrylate) (PHEA) hydrogels prepared by in situ polymerization under sustained mechanical mixing, and further modified with glycerol, exhibit robust mechanical integrity, high adhesiveness and enhanced moisture retention, illustrating how rationally designed synthetic networks can overcome dehydration and poor adhesion in conventional aqueous hydrogels [14].

Hydrocolloid dressings, typically composed of gelatin, pectin and carboxymethylcellulose dispersed in an adhesive matrix, remain a standard of care for superficial wounds and pressure ulcers with low to moderate exudate [1,2]. Upon exudate absorption, they form a cohesive gel and provide an occlusive moist environment. Compared with hydrogels, hydrocolloids are generally more occlusive and can be worn for longer periods, but may increase the risk of maceration or anaerobic infection when exudate is excessive [1]. Recent work often uses hydrocolloids as baseline comparators, while hydrogel and foam dressings are optimized and tailored for more demanding clinical scenarios [2,4].

ECM-derived and bioinspired dressings

ECM-based dressings aim to recapitulate the structural and biochemical cues of native dermis. Decellularized dermal matrices, small-intestinal submucosa, amniotic membrane and fish-derived acellular matrices preserve collagen, elastin, proteoglycans and growth factor binding domains that support cell adhesion, migration and angiogenesis [15-18]. Recent studies indicate that decellularized ECM dressings can accelerate re-epithelialization and shorten healing time in preclinical models of chronic and burn wounds, although clinical data remain heterogeneous and indication-specific [15,16].

Current trends include combining decellularized ECM with synthetic or natural polymers, such as polyethylene glycol, gelatin methacrylate or polysaccharide-based hydrogels, to tune mechanical properties, degradation rate and injectability [17,18]. Bioadhesive motifs are also integrated for suture-less fixation. These composite matrices may better bridge large defects, improve handling in the operating room and provide a favorable niche for stem cells or host progenitor cells [15-18].

Drug-loaded and stimuli-responsive dressings

Drug-eluting dressings offer localized, sustained delivery of antimicrobials (for example, silver agents, antibiotics, antiseptics), anti-inflammatory drugs, growth factors or pro-angiogenic small molecules [2,10-13]. Nano-based hydrogel dressings that incorporate metallic, polymeric or lipid nanoparticles have shown particular promise for diabetic wounds, where infection, impaired perfusion and persistent inflammation frequently coexist [11-13]. Recent systems incorporate ROS-responsive linkages, pH-triggered release or enzyme-cleavable motifs, which enable on-demand drug release in response to the local wound milieu [11-13]. In addition to these chemical triggers, a variety of physical stimuli have also been explored, including thermo- and light-responsive matrices that release antibiotics or growth factors upon near-infrared irradiation, as well as mechano-responsive hydrogels that accelerate drug liberation when compressed or stretched during limb movement. Glucose-responsive systems are particularly attractive for diabetic foot ulcers, where phenylboronic-acid-containing networks or glucose-sensitive nanoparticles can couple local hyperglycemia to feedback-controlled delivery of anti-inflammatory or proangiogenic agents.

ECM-inspired or collagen-containing hydrogels loaded with bioactive compounds have also been investigated, for instance photo-crosslinked silk fibroin-collagen analog hydrogels that enhance closure of diabetic and burn wounds [15-18]. As regulatory expectations for combination products become clearer, translation of such drug-loaded matrices into clinical practice is likely to accelerate, especially when they address unmet needs such as multidrug-resistant infection or ischemic wounds that respond poorly to conventional dressings [1,2,10-13]. However, widespread clinical adoption of such drug-loaded dressings still faces important hurdles, including reproducible large-scale manufacturing, long-term stability of encapsulated agents, and the need to navigate regulatory pathways for device-drug or devicebiologic combination products. These aspects must be carefully addressed to ensure consistent performance and patient safety in clinical use.

Pressure- and electricity-assisted wound therapy

NPWT has become a cornerstone for managing large, exudative or infected wounds. By applying sub-atmospheric pressure through a foam interface under an occlusive drape, NPWT removes exudate and contaminated fluid, reduces edema, increases perfusion and induces macro- and micro-deformation at the wound bed, which stimulates granulation tissue formation and wound contraction [1,5,6]. Meta-analyses suggest that this modality can improve healing and reduce amputation rates in diabetic foot ulcers and other complex wounds when combined with appropriate debridement and infection control [5,6].

Electrical stimulation exploits endogenous bioelectric fields that guide keratinocyte and fibroblast migration. Low-intensity direct or pulsed currents can accelerate closure, enhance angiogenesis and modulate inflammation in both preclinical and clinical studies [7]. Recent work describes wearable electroceutical dressings that integrate microelectrodes with soft hydrogels or textile substrates, as well as self-powered systems based on triboelectric, piezoelectric or galvanic mechanisms, which harvest body motion or moisture to generate therapeutic currents without bulky external power supplies [8,9]. These platforms can be combined with drug-loaded hydrogels or ECM matrices to create multimodal dressings that deliver both biochemical and electrical cues [7-13].

Outlook: Toward smart, integrated wound dressing systems

A converging trend is the integration of sensors, feedback control and data connectivity into wound dressings. Flexible sensors embedded in hydrogels or films can track pH, temperature, oxygen, glucose or biomarkers of infection, while wireless modules transmit data to clinicians and support artificial intelligence-based decision making [19,20]. When coupled with actively actuated elements such as drug reservoirs, heaters or electrical stimulation modules, these systems can form closed-loop platforms for personalized wound care [8,9,19,20]. Key challenges include ensuring robustness in a humid, protein-rich environment, simplifying user interfaces for patients and nurses, and addressing cost, training and reimbursement issues in routine clinical practice [1,19,20]. Beyond technical feasibility, smart dressings will also need to demonstrate clear health-economic benefits. Higher up-front costs for sensorintegrated or electronically assisted systems must be justified by faster healing, fewer clinic visits and hospitalizations, and reduced rates of complications such as infection or amputation. Generating such evidence through well-designed comparative effectiveness trials will be essential for favorable reimbursement and guideline inclusion.

Conclusion

Recent advances in wound dressings reflect a clear transition from passive coverings to bioactive, drug-loaded and electronically assisted systems that directly modulate the wound microenvironment. Hydrogels and hydrocolloids remain essential moist-retentive platforms, while ECM-derived matrices better recapitulate native tissue architecture and signaling. Drug-loaded and stimuli-responsive dressings enable localized control of infection, inflammation and angiogenesis. Negative pressure wound therapy and electroceutical dressings superimpose mechanical and electrical cues that have demonstrated clinical benefit in selected patient groups. Early smart dressings that integrate sensing, actuation and connectivity illustrate the potential for highly personalized, data-driven wound care. Future work should prioritize rigorous clinical validation, standardized outcome measures and scalable manufacturability, while maintaining a strong link between rational materials design and the complex pathophysiology of chronic wounds.

References

- Han G, Ceilley R (2017) Chronic wound healing: A review of current management and treatments. Advances in Therapy 34(3): 599-610.

- Alberts A, Tudorache DI, Niculescu AG, Grumezescu AM (2025) Advancements in wound dressing materials: Highlighting recent progress in hydrogels, foams, and antimicrobial dressings. Gels 11(2): 123.

- Yu P, Liu L, Wei L, Yang Z, Liu X, et al. (2024) Hydrogel wound dressings accelerating healing process of wounds in movable parts. Int J Mol Sci 25(12): 6610.

- Zhang W, Liu L, Cheng H, Zhu J, Li X, et al. (2024) Hydrogel-based dressings designed to facilitate wound healing. Mater Adv 5(4): 1364-1394.

- Deng YX, Wang XC, Xia ZY, Wan MY, Jiang DY (2025) Efficacy and safety of negative pressure wound therapy for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: A meta-analysis. World J Diabetes 16(6):103520.

- Du Y, Zhai T, Sheng Z, Xie W, Jia Z, et al. (2025) Efficacy and safety of negative pressure wound therapy in diabetic foot ulcers: A cross-sectional analysis of overlapping meta-analyses. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 18: 1931-1945.

- Preetam S, Ghosh A, Mishra R, Pandey A, Roy DS, et al. (2024) Electrical stimulation: A novel therapeutic strategy to heal biological wounds. RSC Adv 14(44): 32142-32173.

- Kaveti R, Jakus MA, Chen H, Jain B, Kennedy DG, et al. (2024) Water-powered, electronics-free dressings that electrically stimulate wounds for rapid wound closure. Sci Adv 10(32): eado7538.

- Mutah AA, Amitrano J, Seeley MA, Seshadri D (2025) A review of wearable electroceutical devices for chronic wound healing. Electronics 14(7): 1376.

- Alberts A, Moldoveanu ET, Niculescu AG, Grumezescu AM (2025) Hydrogels for wound dressings: Applications in burn treatment and chronic wound care. J Compos Sci 9(3): 133.

- Zhang X, Wei P, Yang Z, Liu Y, Yang K, et al. (2023) Current progress and outlook of nano-based hydrogel dressings for wound healing. Pharmaceutics 15(1): 68.

- Jia B, Li G, Cao E, Luo J, Zhao X, et al. (2023) Recent progress of antibacterial hydrogels in wound dressings. Mater Today Bio 19: 100582.

- Arbab S, Ullah H, Muhammad N, Wang W, Zhang J (2024) Latest advance anti-inflammatory hydrogel wound dressings and traditional lignosus rhinocerotis used for wound healing agents. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 12: 1488748.

- Kim SY, Kang JW, Jeong EH, Kim T, Jung HL et al. (2024) Synthesis of bioadhesive PHEA hydrogels without crosslinkers through in situ polymerization and sustained mechanical mixing. Korea-Australia Rheology Journal 36(1): 71-78.

- Liang R, Pan R, He L, Dai Y, Jiang Y, et al. (2025) Decellularized extracellular matrices for skin wound treatment. Materials (Basel) 18(12): 2752.

- Solarte David VA, Güiza-Argüello VR, Arango-Rodríguez ML, Sossa CL, Becerra-Bayona SM (2022) Decellularized tissues for wound healing: Towards closing the gap between scaffold design and effective extracellular matrix remodeling. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 10: 821852.

- Xu P, Cao J, Duan Y, Kankala RK, Chen A (2024) Recent advances in fabrication of dECM-based composite materials for skin tissue engineering. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 12: 1348856.

- Hosty L, Heatherington T, Quondamatteo F, Browne S (2024) Extracellular matrix-inspired biomaterials for wound healing. Mol Biol Rep 51(1): 830.

- Prakashan D, Kaushik A, Gandhi S (2024) Smart sensors and wound dressings: Artificial intelligence-supported chronic skin monitoring -a review. Chem Eng J 497: 154371.

- Vo DK, Trinh KTL (2025) Advances in wearable biosensors for wound healing and infection monitoring. Biosensors 15(3): 139.

© 2025 Byoung Soo Kim. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)