- Submissions

Full Text

Cohesive Journal of Microbiology & Infectious Disease

Isolation, Characterization and Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiling of ESBL E. coli in Retail Chicken

Syed Hamza Abbas1, Pir Osama Syed Yousafzai2, Muhammad Abbas5, Taskeen Ali Khan1, Shahzar Khan1, Talha Khan3, Aliya Khalid2*, Aftab Ali4 and Kainat Rahim1

1 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biological sciences, Quaid- I- Azam University, Pakistan

2 Department of Microbiology, Abdul Wali khan university, Pakistan

3 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Biological sciences Quaid-I-Azam University, Pakistan

4 Department of Allied Health Sciences, Iqra National University, Swat Campus, Pakistan

5 Department of Molecular Biology Uskudar University Istanbul, Turkey

*Corresponding author: Aliya Khalid, Department of Microbiology, Abdul Wali Khan University, Pakistan

Submission: January 20, 2026;Published: February 17, 2026

ISSN 2578-0190 Volume8 issues 1

Abstract

The development of Extended-Spectrum B-Lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli and thus Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) are emerging as an increasing concern in the public health domain. This was done to isolate, identify and describe ESBL producing E. coli of retail chicken meat in different districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) in Pakistan. One hundred (100) unwrapped and fresh poultry meat samples were picked in local markets and butchers in Mardan, Nowshera, Swabi and Charsadda. Samples were incubated in modified Tryptone Soya Broth (mTSB) and grown on MacConkey agar with biochemical confirmation of the growth being done through the standard tests (Indole, MR, VP and TSI). Additional identification was based on gram staining and colony morphology. The screening of E. coli was done with cefotaxime-supplemented agar and the susceptibility to antibiotics was measured through the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion test on the Mueller-Hinton agar as per the CLSI standards. Out of the isolates, 25 were also confirmed to be ESBL-producing E. coli. All 25 (100 per cent) resistant to third-generation cephalosporins (ceftoxime, ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefepime) and b-lactam/b-lactamase inhibitor (amoxicillin-clavulanacid, cefotaxime-clavulanate, ceftazidime-clavulanate). The zone diameters were always within the resistant range (6-14mm), no intermediary or vulnerable profiles were found. These results provide support to the fact that the B-lactam resistance in the E. coli strains obtained due to retail chicken meat is high and this implies that there is a pathway through the food chain that could be used to transmit the resistance to humans. This paper indicates the urgent necessity of strong food safety measures, regular monitoring, as well as antibiotic stewardship to reduce the proliferation of multidrugresistant bacteria in society.

Introduction

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is a health issue that is quickly becoming a major problem on a global level and it is estimated that by the year 2050, it may cause up to 10 million deaths [1-3]. One of the key reasons that have led to this crisis is the growing prevalence of Extended- Spectrum B-Lactamases (ESBLs), which are enzymes that allow bacteria to inactivate a wide range of b-lactam antibiotics, including third-generation cephalosporins [4-6]. Most of these enzymes are produced by Gram-negative bacteria including Escherichia coli (E. coli), a versatile pathogen which can exist in a form of a non-pathogenic commensal in the gut and a cause of severe infections in people [7,8]. E. coli is also reported to lead to numerous diseases, such as urinary tract infections, septicemia and gastroenteritis caused by food-borne [9,10]. The presence of ESBL-producing strains of E. coli is particularly alarming because it is more likely to be co-resistant to several classes of antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides [11,12]. This issue is severe as the level of ESBLproducing E. coli is reported as 40-70% in some developing countries according to new surveillance reports. The food chain is one of the most significant pathways of transmission of resistant bacteria to humans [13-15]. The use of poultry meat especially chicken is done on a high scale across the world with the annual global production standing at more than 130 million tones. Nevertheless, about 60% of all antibiotics administered to food-producing animals target growth promotion and disease prevention, which is the poultry industry [16,17]. Research has revealed that as many as 80 percent of raw chicken meat samples contain E. coli and 20-40 percent of these isolates have been determined to be ESBL producers. The contamination usually happens during the processing stage when the intestinal contents are in contact with meat [18,19]. In case of improper hygiene or improper cooking or handling of meat, there are chances of transmission of the ESBL-producing bacteria to consumers, which directly endanger human health. This risk is even more significant in developing countries where food safety standards might be not systematically implemented [20,21]. Considering such alarming epidemiological issues, careful attention should be paid to the prevalence and resistance patterns of ESBL-producing E. coli in the retail food production, particularly in poultry products of massive consumption. The overall objective of this research is to isolate, identify and biochemically characterize Escherichia coli strains in retail chicken meat with a particular emphasis on identifying the antibiotic susceptibility of the isolates and the identification of ESBL-producing isolates. The results will be useful information in the comprehension of antimicrobial resistance in the food chain and help create effective food safety and public health interventions.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

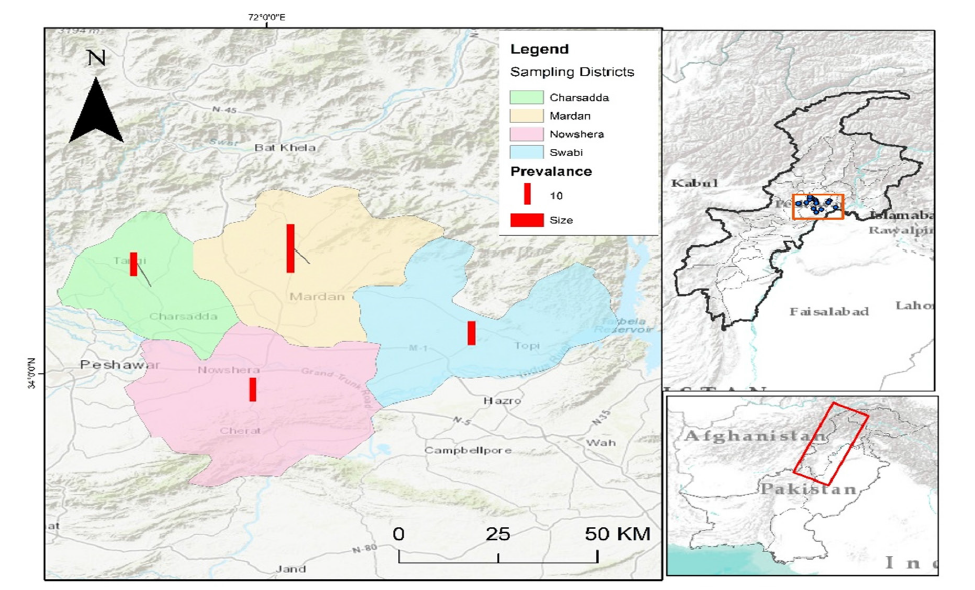

One hundred retail poultry meat samples were collected in the different districts in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Pakistan. The sampled areas were local markets and butcher shops at Mardan, Nowshera, Swabi and Charsadda. One hundred forty samples were taken in Mardan in various localities like Takht Bhai, Ganjai, Seri Behlol, Jandai, Gujar Garhi, College Chowk and Shaikh Maltoon. Nowshera has provided 20 samples, which were extracted in Main City, Kaka Saib and Akora Khattak. On the same note, Swabi samples 20 samples were sampled on Kalo Khan, Ambaar and Yar Hussain whereas Charsadda provided 20 samples sampled in Saro Shah, Gul Abad and Sar Dheri. All samples were fresh, unpackaged and displayed openly for consumer selection. Each sample was aseptically collected and transported under chilled conditions to the National Veterinary Laboratory, Islamabad, for further microbiological analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Geographical distribution of retail poultry meat sampling sites (n=100) across districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, including Mardan (40 samples), Nowshera (20), Swabi (20) and Charsadda (20).

Sample processing and enrichment

From each chicken meat sample, 15-20 grams were aseptically removed from the sub-epithelial surfaces of the thigh and chest regions using sterile scissors and forceps. The meat portions were then inoculated into 10mL of Modified Tryptone Soya Broth (mTSB) in sterile test tubes and incubated at 37 °C for 24 to 48 hours. After incubation, the samples were checked for turbidity indicating microbial growth. Gram staining and a series of biochemical tests were used to preliminarily identify E. coli and other bacterial contaminants.

Preparation of Modified Tryptone Soya Broth (mTSB)

Modified Tryptone Soya Broth (mTSB) was prepared by dissolving 30 grams of TSB powder in 1 liter of distilled water, supplemented with 1.5-3 grams of bile salts and 1.5 grams of dipotassium phosphate to enrich for enteric bacteria, including ESBL-producing E. coli. The medium was autoclaved at 121 °C for 15 minutes, cooled and then dispensed into sterile tubes in 10mL aliquots. Fresh meat samples were inoculated into these tubes and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours.

Culture and isolation

After enrichment, agar plates of MacConkey were used to culture the samples, which is a selective and differentiation medium that is appropriate in the isolation of Gram-negative bacteria. The plates were cultivated at 37 °C in 24 hours aerobically. The colonies that revealed pink or red color (a characteristic of lactose- fermenting bacteria like E. coli) were picked to undergo further identification. MacConkey agar: 50 grams of the dehydrated medium were dissolved in 1 liter of distilled water after which it was autoclaved at 121 °C and 15 minutes. The medium was then cooled to 50 °C and then put in sterile Petri dishes and allowed to solidify.

Preparation of Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA)

Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) was prepared manually as follows: 1.5ml of blood were collected and combined with 3.4ml of chloramphenicol-impregnated blood (Ulrich, 2006). Isolated colonies were sub-cultured onto MHA (Mueller-Hinton agar, (MHA) a non-selective agar that was used in testing the susceptibility of particular isolates to antibiotics. MHA was made by dissolving 53 grams of medium in 1 liter of distilled water, boiling the solution and autoclaving at 121 °C 15 minutes and cooled to a room temperature before adding it to Petri plates. Plates were kept at 8-15 °C until further usage.

Morphological identification

Preliminary morphological identification was done by gram staining. The staining technique consisted of four major steps, namely crystal violet (primary stain), Gram’s iodine (mordant), alcohol-acetone (decolorizer) and safranin (counterstain). E. coli being gram-negative bacteria were pink-red under the microscope whereas Gram-positive bacteria did not lose the crystal violet and turned blue or purple.

Biochemical identification

Presumptive identification of E. coli isolates was done through a number of standard tests. The indole test was employed to establish the capacity of the organism to degrade tryptophan in order to produce indole. After adding the reagent of Kovac to the medium, a red ring at the surface of the medium had been observed, which was a positive result. The glucose fermentation was stable because it was tested using the Methyl Red (MR) test and upon the addition of the indicator, methyl red, a red color was formed indicating a positive test. Voges-Proskauer (VP) test identified the formation of acetoin as a result of glucose metabolic process; the red or pink color formation in the presence of a-naphthol and potassium hydroxide was a positive test outcome. Carbohydrate fermentation (glucose, lactose and sucrose) and Hydrogen Sulfide (H2S) production were measured by the Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) test. Yellow butt and /or slant was a result of sugar fermenting, whereas black precipitate represented H2S. The impact of antibiotics on gram-positive microbes differs from that on gram-negative microbes (Ong and Chen 215).

Antibiotic susceptibility testing and ESBL detection

Enriched cultures were pre-incubated on MacConkey agar with the addition of cefotaxime and incubated at 37 °C for 48 hours to identify ESBL production. Mueller-Hinton agar sub-cultures were then made of colonies that were suggestive of E. coli. The disk diffusion procedure was done as per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). The antibiotics that were tested were ceftriaxone, ceftazidime, cefepime, cefotaxime+clavulanic acid, ceftazidime+clavulanic acid, cefoxitin and amoxicillin+clavulanic acid. ESBL-producing isolates were finally confirmed using the standard broth microdilution method at the National Veterinary Laboratory, Islamabad.

Results

Sample isolation and processing

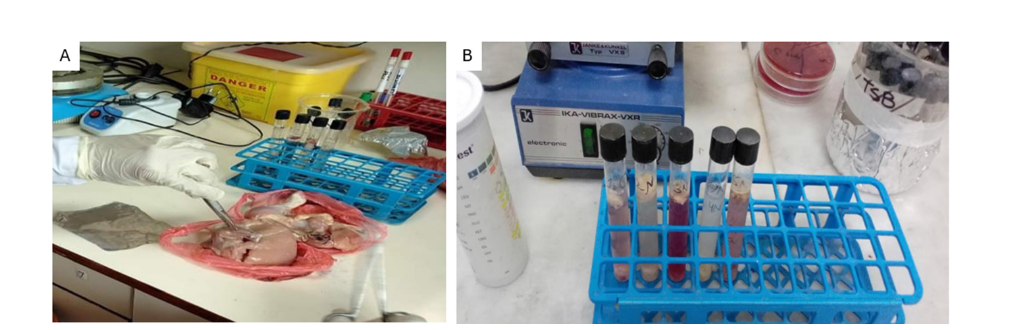

The sample was collected using simple random sampling methods with processing carried out as outlined below: Sample meats were collected aseptically using sterile forceps and a sterile scissor on the sub-epithelial surfaces of the thigh and chest of chicken (Figure 2A). The samples were inoculated then into Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB) which is a nutrient-enriched medium that are appropriate in the recovery of enteric bacteria. The inoculated tubes were incubated at 37 °C and let 48 hours to enrich and propagate the potential bacterial contaminants (Figure 2B). Turbidity of the broth was used as a measure of bacterial growth and the samples could be used in selective isolation and additional characterization.

Figure 2: (A) Isolation of sub-epithelial chicken meat sample (B) enrichment of samples in Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB).

Bacterial identification

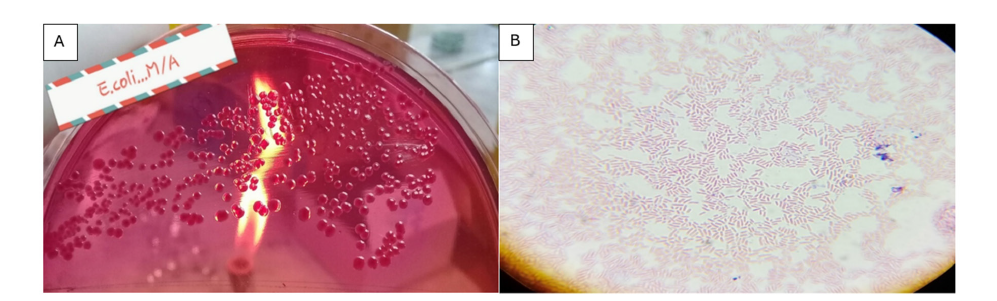

Per the enrichment step, cultures were streaked on MacConkey agar plates to selectively isolate Gram-negative lactose-fermenting bacteria. After giving incubation of 24 hours at 37 °C, one was able to observe very distinct pink-colored colonies (Figure 3A). This was a sign of lactose fermenting Gram-negative bacteria a characteristic feature of Escherichia coli. Gram staining was done in order to identify the isolates. The microscopic analysis showed that the bacteria were pink, rods and this was in line with the morphological features of Gram-negative E. coli (Figure 3B).

Figure 3: (A) Pink colonies on MacConkey agar indicating lactose fermentation by E. coli (B) Microscopic image showing Gram-negative rod-shaped bacteria (E. coli).

Biochemical identification

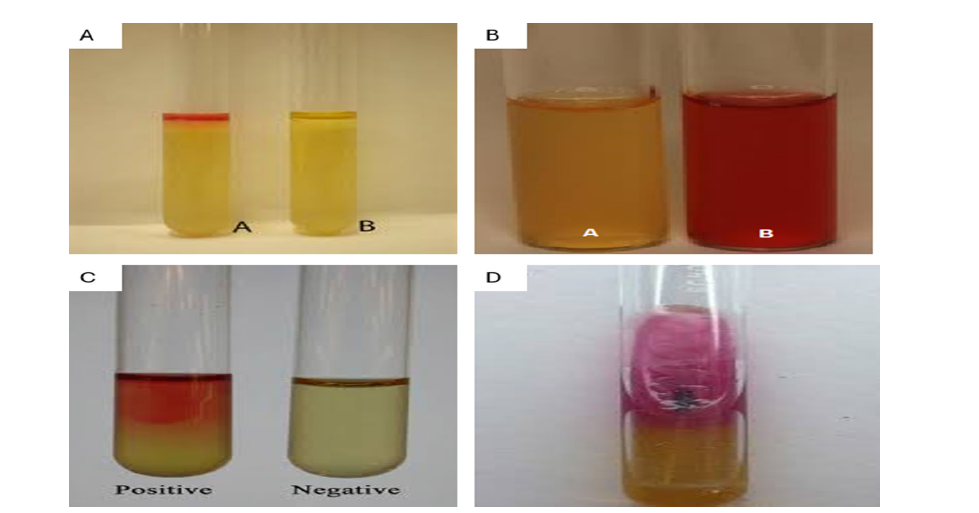

In this step, the precise biochemical characteristics of the unknown are determined using a selected set of biochemical tests Biochemical Identification This step involves the identification of the exact biochemical properties of the unknown through a chosen repertoire of biochemical tests. To eliminate any confusion of the E. coli isolates, biochemical tests were conducted. When the reagent of Kovac was added, a red ring was formed in the Indole test and it is a positive indication of the production of indole (Figure 4A). Methyl Red (MR) test also indicated a positive result because the broth changed to red upon the addition of the MR indicator (Figure 4B). The Voges-Proskauer (VP) test showed the appearance of a red color after the addition of alpha-naphthol and potassium hydroxide which indicated that acetoin was produced (Figure 4C). Triple Sugar Iron (TSI) test showed the formation of gases and black precipitates, which indicated that sugars were fermented and black was produced (Figure 4D). These findings are in agreement with the biochemical profile of the Escherichia coli, which establishes the identity of the isolates.

Figure 4: (A) Positive Indole test for E. coli (B) Positive Methyl Red test for E. coli (C) Positive VP test for E. coli (D) TSI test showing gas and H2 S production by E. coli.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing of ESBL-producing E. coli

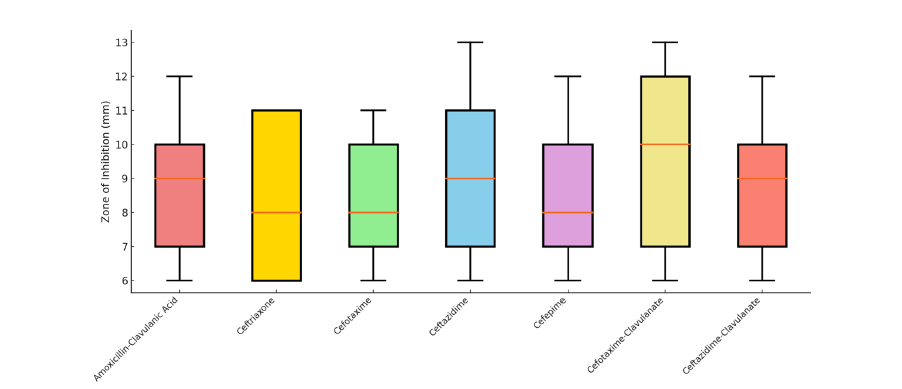

Antibiotic susceptibility testing was carried out on 25 isolates of Escherichia coli confirmed as Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL) producers using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar. The antibiotic panel included third-generation cephalosporins and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations. The results revealed widespread resistance: 100% (25/25) of the isolates were resistant to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime and cefepime. The zone of inhibition for cefotaxime ranged from 6-12mm, for ceftazidime from 6-14mm and for cefepime from 6-13mm, all of which fall within the resistant range according to CLSI guidelines. Even the addition of β-lactamase inhibitors showed no therapeutic advantage. For cefotaximeclavulanate, the zone diameter was ≤14mm in all isolates, with 100% resistance (25/25). Similarly, ceftazidime-clavulanate showed zones between 8-13 mm, also indicating 100% resistance. No intermediate or susceptible strains were recorded for any of the tested antibiotics. These findings strongly suggest the presence of high-level β-lactam resistance, with complete therapeutic failure of both third-generation cephalosporins and their combinations with β-lactamase inhibitors. Overall, the study indicates a critical resistance pattern, highlighting that 25 out of 25 isolates (100%) showed multidrug resistance, with 0% susceptible and 0% intermediate reactions across the tested β-lactam class agents. This underscores the urgent need for antibiotic stewardship and the surveillance of ESBL-producing organisms in poultry-derived food products (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Distribution of Zone of Inhibition (mm) for ESBL-Producing E. coli Isolates (n=25) Against Various β-Lactam Antibiotics and Inhibitor Combinations.

Discussion

The current research indicates the frightening rate of the spread of Extended-Spectrum B-Lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli in retail chicken meat of different districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK), Pakistan. This 100 percent resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and b-lactam/b-lactamase combinations is in line with other reports that have reported the global dissemination of Multidrug-Resistant (MDR) E. coli of food sources [22,23]. Such results highlight the increasing risk of AMR bacteria to the health of the population in the food chain, especially in the areas where the use of antimicrobials is controlled inadequately. The resistance rates of this research are similar to those in other developing nations, where poultry meat is most often contaminated with resistant strains of E. coli because antibiotics are used in a non-therapeutic manner to promote growth and prevent diseases [21,24]. Furthermore, the lack of effects of b-lactamase inhibitor combinations, including cefotaxime-clavulanate and ceftazidimeclavulanate, indicates that the isolates have the high-level resistance mechanisms, which may include the plasmid-mediated ESBL genes, such as blaCTX-M or blaTEM or bla-SHV, that have been extensively reported in poultry-associated E. coli [23,25], 2 Such a practice of using poultry as a means of transmission of MDR bacteria to human beings is particularly worrisome in Pakistan where the consumption of poultry is high and food safety practices fluctuate. Contamination of the meat handling environment and slaughter also contribute to the spread of resistant strains [26,27]. When transferred to human beings, such bacteria may lead to infections that can hardly be cured, particularly among the immunocompromised people. This paper highlights the necessity to develop encompassing One Health strategies to fight AMR. The interventions that ought to be taken at the policy level are the tightening of regulations on the use of antimicrobials in livestock, the enhancement of good hygiene in the slaughterhouse and the sensitization of the people on the safe handling and cooking methods of meat. Moreover, molecular characterization of resistance genes and surveillance should be increased at the farm level and retail level in order to monitor trends in AMR.

Conclusion

The findings of this study reveal a concerning prevalence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in retail chicken meat sourced from various districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. All confirmed isolates demonstrated complete resistance to thirdgeneration cephalosporins and β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, indicating a high level of antimicrobial resistance. This suggests that poultry meat serves as a significant reservoir and potential transmission route for multidrug-resistant pathogens to humans through the food chain. The results underscore the urgent need for improved antibiotic stewardship in the poultry industry, stricter regulatory oversight and public health interventions aimed at enhancing food safety, surveillance and awareness. Without immediate action, the unchecked spread of ESBL-producing bacteria poses a serious threat to both animal and human health [28-30].

References

- Ali Syed I, Alvi IA, Fiaz M, Ahmad J, Butt S, et al. (2024) Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Ganoderma species and their activity against multi drug resistant pathogens. Chemistry & Biodiversity 21(4): e202301304.

- Javed S, Ahmad J, Zareen Z, Iqbal Z, Hubab M, et al. (2023) Study on awareness, knowledge, and practices towards antibiotic use among the educated and uneducated people of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province, Pakistan. ABCS Health Sciences 48: e023218-e023218.

- Rehman A, Bashir K, Farooq S, Khan A, Hassan N, et al. (2023) Molecular analysis of aminoglycosides and β-lactams resistant genes among urinary tract infections. Bulletin of Biological and Allied Sciences Research 8(1): 56-56.

- Ahmad J, Ahmad S, Shfiq Z, Mehmood A, Zafar S, et al. (2023) Simultaneous application of non-antibiotics with antibiotics for enhanced activity against multidrug resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Pharmaceutical Negative Results 14(3): 4015-4023.

- Khan S, Fiaz M, Alvi IA, Ikram M, Yasmin H, et al. (2023) Molecular profiling, characterization and antimicrobial efficacy of silver nanoparticles synthesized from Calvatia gigantea and Mycena leaiana against multidrug-resistant pathogens. Molecules 28(17): 6291.

- Laraib S, Lutfullah G, Bukhari JA, Almuhayawi MS, Ullah M, et al. (2023) Exploring the antibacterial, antifungal, and anti-termite efficacy of undoped and copper-doped ZnO nanoparticles: Insights into mutagenesis and cytotoxicity in 3T3 cell line. Journal of Biological Regulators and Homeostatic Agents 37(12): 6731-6741.

- Munir S, Amanat T, Raja MA, Mohammed K, Rasheed RA, et al. (2023) Antimicrobial efficacy of phyto-synthesized silver nanoparticles using aqueous leaves extract of rosamarinus officinalis L. Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 36(3): 941-946.

- Shah R, Sarosh I, Shaukat R, Alarjani KM, Rasheed RA, et al. (2023) Antimicrobial activity of AgNO 3 nanoparticles synthesized using Valeriana wallichii against ESKAPE pathogens. Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 36(2): 699-706.

- Ahmad B, Abro R, Kabir A, Rehman B, Khattak F, et al. (2022) Effect of feeding different levels of Escherichia coli phytase and Buttiauxella phytase on the growth and digestibility in broiler. Pakistan Journal of Medical & Health Sciences 16(07): 700-700.

- Aziz A, Ahmad B, Ateeq M, Gulfam N, Bangash SA, et al. (2022) Isolation and identification of MDR Solmonella typhi from different food products in district Peshawar, KPK, Pakistan. Tobacco Regulatory Science (TRS), pp. 555-572.

- Abdullah M (2022) Effect of pure and ethanol extract of aloe vera and moringa against Streptococcus agalactiae and Staphylococcus aureus Isolated from Mastitis Milk of Buffalo. Tobacco Regulatory Science (TRS), pp. 959-976.

- Khalil MS, Shakeel M, Gulfam N, Ahmad SU, Aziz A, et al. (2022) Fabrication of silver nanoparticles from Ziziphus nummularia fruit extract: Effect on hair growth rate and activity against selected bacterial and fungal strains. Journal of Nanomaterials 2022(1): 3164951.

- Ahamd J, Khan W, Khan MK, Shah K, Yasir M, et al. (2022) Antimicrobial resistant and sensitivity profile of bacteria isolated from raw milk in Peshawar, KPK, Pakistan. Ann Roman Soc Cell Biol 26(1): 364-374.

- Aziz A, Zahoor M, Aziz A, Asghar M, Ahmad J, et al. (2022) Identification of resistance pattern in different strains of bacteria causing septicemia in human at lady reading hospital of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Pakistan Journal of Medical & Health Sciences 16(08): 687-687.

- Hayat S, Ahmad J, Khan HA, Tara T, Ali H, et al. (2022) Antimicrobial Activity of Rhizome of Christella dentata. (forsk.) Brownsey & Jermy Against Selected Microorganisms. Tobacco Regulatory Science.

- Ahmad J, Pervez H (2021) Antimicrobial activities of medicinal plant Rhamnus virgata (Roxb.) Batsch from Abbottabad, Nathia Gali, KPK, Pakistan. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology 25(7): 1502-1511.

- Ullah I, Khurshid H, Ullah N, Aziz I, Khan MJ, et al. (2019) Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of Campylobacter species isolated from broiler chicken meat samples in district Bannu, Pakistan. Journal of Food Safety and Hygiene 5(4): 230-236.

- Khan MK, Arif MR, Ahmad J, Azam S, Khan RM, et al. (2021) Microbial load and antibiotic susceptibility profile of bacterial isolates from drinking water In Peshawar, Pakistan. Nveo-Natural Volatiles & Essential Oils Journal| NVEO 8(6): 4759-4765.

- Ur Rehman AB, Naila IU, Ahmad ZA (2021) A review of global epidemiology and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus Aureus. Pakistan Journal of Medical & Health Sciences 15(12): 3921-3927.

- Badr H, Reda RM, Hagag NM, Kamel E, Elnomrosy SM, et al. (2022) Multidrug-resistant and genetic characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing coli recovered from chickens and humans in Egypt. Animals 12(3): 346.

- Liaqat Z, Khan I, Azam S, Anwar Y, Althubaiti EH, et al. (2022) Isolation and molecular characterization of extended spectrum beta lactamase producing Escherichia coli from chicken meat in Pakistan. PLoS one 17(6): e0269194.

- Jaiswal A, Khan A, Yogi A, Singh S, Pal AK, et al. (2024) Isolation and molecular characterization of multidrug‑resistant Escherichia coli from chicken meat. 3 Biotech 14(4): 107.

- Lemlem M, Aklilu E, Mohamed M, Kamaruzzaman NF, Devan SS, et al. (2024) Prevalence and molecular characterization of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli isolated from broiler chicken and their respective farms environment in Malaysia. BMC Microbiology 24(1): 499.

- Rahman MM, Husna A, Elshabrawy HA, Alam J, Runa NY, et al. (2020) Isolation and molecular characterization of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli from chicken meat. Scientific Reports 10(1): 21999.

- Eltai NO, Abdfarag EA, Al-Romaihi H, Wehedy E, Mahmoud MH, et al. (2018) Antibiotic resistance profile of commensal Escherichia coli isolated from broiler chickens in Qatar. Journal of food protection 81(2): 302-307.

- Ahmad K, Khattak F, Ali A, Rahat S, Noor S, et al. (2018) Carbapenemases and extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from retail chicken in Peshawar: First report from Pakistan. Journal of food protection 81(8): 1339-1345.

- Saeed MA, Saqlain M, Waheed U, Ehtisham-ul-Haque S, Khan AU, et al. (2023) Cross-sectional study for detection and risk factor analysis of ESBL-producing avian pathogenic Escherichia coli associated with backyard chickens in Pakistan. Antibiotics 12(5): 934.

- Parvin MS, Talukder S, Ali MY, Chowdhury EH, Rahman MT, et al. (2020) Antimicrobial resistance pattern of Escherichia coli isolated from frozen chicken meat in Bangladesh. Pathogens 9(6): 420.

- Sharma A, IJ Martins (2023) The role of microbiota in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Scientific Nutritional Health 7(7): 108-118.

- IJ Martins (2018) Bacterial lipopolysaccharides and neuron toxicity in neuro generative diseases. Neurology Research and Surgery 2(3): 1-3.

© 2026, Aliya Khalid. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)