- Submissions

Full Text

Biodiversity Online J

Techno-Economic and Environmental Assessment of a Photovoltaic Pumping Installation for Vegetable Irrigation in Casamance, Senegal

Mamadou S1,2*, Baboucar F2 and Alioune N2

1 Paris Nanterre University, France

2 Assane Seck University of Ziguinchor, Senegal

*Corresponding author:Mamadou Sow, Paris Nanterre University, LEME, 50 rue de Sèvres, 92410 Ville d’Avray, Francea

Submission: December 09,2025; Published: January 22, 2026

ISSN 2637-7082Volume5 Issue 5

Abstract

This study presents a Photo Voltaic (PV) water pumping system for agricultural irrigation in Ziguinchor, designed to replace conventional diesel pumps. The system comprises solar panels, a submersible pump, elevated water tanks, and an irrigation network, providing reliable water supply to crops while reducing fuel consumption. Pumping 7m³/h from Total Dynamic Head of 30m requires approximately 572.25W of hydraulic power, corresponding to 1780W of photovoltaic generator power considering a system efficiency of 45%. The solar pump avoids Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) emissions from diesel use, estimated at 2.68kg of CO₂ per liter of fuel, and reduces operating costs, making the levelized cost of hydraulic energy lower than diesel after 2-4 years. Additionally, it can increase annual irrigation volume by 20-50%, improving agricultural productivity and revenue. PV pumping thus offers a sustainable, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly alternative to diesel pumps.

Keywords: Photovoltaic pumping; Vegetable irrigation; Ecological impact; Techno-economic; Casamance

Abbreviations: ρ: Density; g: Gravitational Acceleration; CO2: Carbon Dioxide; P: Panel; W: Watt; t: time; TDH: Total Dynamic Head; PV: Photovoltaic; V: Volume; I: Irradiance

Introduction

Senegal, located in West Africa and characterized by a Sudanian-Sahelian climate, experiences a short rainy season of approximately four months. This climatic constraint poses a major challenge for agricultural development, particularly in the context of rising food demand driven by population growth: the national population increased from 14.8 million in 2014 to over 18 million in 2024. To meet these growing needs, irrigation plays a central role, especially in regions with high agricultural potential. Casamance, in the southern part of the country, is notable for its fertile soils and the importance of both rainfed and off-season agriculture. However, despite this potential, the expansion and intensification of agricultural activities remain limited by insufficient access to reliable energy in many rural areas [1]. Diesel pumps, still widely used for irrigation, have several drawbacks [2] as high fuel costs, pollutant emissions, noise, and maintenance requirements. These constraints reduce the efficiency of agricultural operations and hinder the transition toward more sustainable production methods [3]. In this context, solar pumping systems emerge as a strategic alternative [4]. Supported by abundant solar resources, the continuous decline in photovoltaic technology costs, and national policies promoting renewable energy, they offer significant economic, environmental, and operational benefits [5]. Their deployment represents a key lever to improve irrigation efficiency, optimize operating costs, and reduce the carbon footprint of the agricultural sector [6]. The objective of this manuscript is to rigorously assess the environmental and economic impacts of solar pumping systems in Casamance. The analysis will consider local climatic conditions, system technical performance, investment and operating costs, as well as associated socio-economic benefits. The results aim to provide decision-making guidance for the rational and sustainable deployment of these technologies in the region. By replacing thermal pumps, solar pumps contribute to a significant reduction in CO2 emissions. A diesel system used for irrigation consumes on average between 0.3 and 0.7 litters of fuel per cubic meter of pumped water. In Casamance, where irrigation often concerns small horticultural farms, substituting with a solar system can avoid between 1 and 3 tons of CO2 per year, depending on the depth of the well, the volume of water pumped, and the duration of use. Solar systems promote more regular and controlled pumping, which limits overexploitation of aquifers and reduces the risk of soil salinization, particularly in coastal areas of Casamance. The absence of fuel also eliminates the risk of accidental hydrocarbon spills, which are common around diesel pumps [7].

Materials and Methods

Photovoltaic pumping: A case study in Ziguinchor (Casamance)

Figure 1 below shows a photovoltaic pumping installation for agricultural irrigation in Ziguinchor.

Figure 1:Photography of the solar pumping installation for market gardening.

Photography of the solar pumping installation for market gardening.

Photovoltaic solar panels (top right and bottom left images): These modules capture solar energy and convert it into direct current electricity to power the pump. They are mounted on an inclined support to maximize daily sunlight exposure.

Submersible pump (bottom left image): It is submerged in the well or water source and powered directly by the electricity produced by the solar panels. Its role is to transfer water from the source to the reservoir or directly to the irrigation network.

Elevated water tanks (top left image): These tanks store the pumped water to ensure a steady flow even in the temporary absence of sunlight. Their elevation creates the gravitational pressure needed to supply the irrigation network.

Irrigation network (bottom right image): The stored water is distributed across the agricultural plot through pipes and drip emitters, allowing localized and efficient irrigation.

Overall operation: The solar energy captured by the panels powers the submersible pump, which lifts water to the elevated tanks. The water is then distributed by gravity to the crops via the irrigation network. This installation replaces diesel-powered pumps, reducing operating costs and environmental impacts while using a renewable energy source abundant in the region.

This case study in Ziguinchor evaluates the ecological and economic impact of a photovoltaic pumping installation for irrigation in Casamance. The analysis considers local climatic data to estimate the available solar energy and compares the costs and benefits of solar pumping with conventional diesel-powered pumps. The objective is to provide a comprehensive assessment of the technical performance, energy requirements, and environmental and economic advantages of such an installation in this context.

Water demand and storage tank sizing

The water requirements for vegetable irrigation are determined based on crop type, local climate, and irrigation efficiency. This defines the daily water volume needed. The pump flow rate is chosen accordingly. The storage tank is sized to ensure continuous irrigation despite solar intermittency. Its volume (V) is calculated from the pump flow rate (Q) and daily pumping duration (t) using the formula:

V = Q×t (1)

Q: Pump flow rate (m3⁄h)

t: Time (h)

Daily energy requirements

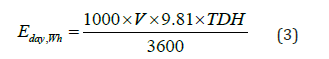

Daily energy requirements (Eday) represent the energy needed to pump a water volume V (m3) to a total dynamic head TDM (m). The mechanical energy in Joule (J) required to lift the water is calculated as:

Eday = ρ × g ×V ×TDH (2)

ρ∶ 1000kg⁄m3 (Water Density)

g∶ 9.81m⁄s2 (gravitational acceleration)

This energy, initially in joules (J), can be expressed in (Wh) with (1Wh=3600 J):

To simplify the calculation of the daily energy required, the physical constants are combined, yielding a more concise form of the equation:

E day,Wh = 2.725× V ×TDH (4)

Efficiency of the installed photovoltaic modules

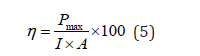

The photovoltaic modules used in this installation are crystalline silicon panels, with a nominal power of (Pmax=280W) and an active surface area of (A=1.64m2).

The actual efficiency (η) of each module in (%) is evaluated based on the module characteristics and the site-specific irradiance (I) using the following equation:

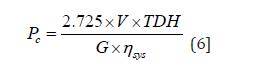

Photovoltaic generator sizing for irrigation

For the installed system, the peak power of the photovoltaic generator was determined based on the maximum daily water demand, which occurs during the hottest month (May in Casamance), and a reference of average daily solar irradiation (G=5kWh/m2.day). The peak power required to operate the pump is calculated using:

G: average daily solar irradiation (kWh/m2·day) ηsys: global system efficiency

Economic assessment

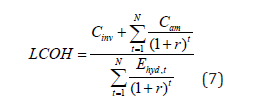

The economic viability of a solar pumping system depends on both the initial investment and the ongoing operating costs. While the upfront cost of photovoltaic panels, pumps, and storage tanks can be significant, solar pumping systems have minimal fuel expenses and lower maintenance requirements compared to diesel pumps. Over the system’s lifetime, these savings often offset the initial investment, making solar pumping a cost-effective solution for small-scale irrigation projects. The LCOH represents the total cost per unit of hydraulic energy over the system’s lifetime, accounting for both investment and annual operation costs.

Cinv: Initial investment cost

Cam: Annual maintenance costs

Ehyd,t: Hydraulic energy produced in year t

r: discount rate

N: system lifetime (in years)

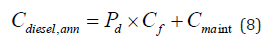

For a diesel pump, the total annual cost is:

Pd: annual fuel consumption (L)

Cf: fuel price (FCFA/L)

Cmaint: maintenance cost

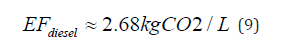

Environmental impact

Solar pumps, by replacing conventional diesel pumps, contribute to a significant reduction in CO2 emissions. A diesel system used for irrigation consumes on average between 0.3 and 0.7 liters of fuel per cubic meter of water pumped. Avoided CO2 Emissions are calculated as below. Diesel pump emits on average

The annual avoided emissions are therefore:

Result and Discussion

The system delivers a daily pumped water volume of 49m3, corresponding to a pump flow rate of 7m2 /h operating for 7 hours per day. This volume is well suited to the irrigation requirements of small-scale vegetable farming and ensures adequate water availability during periods of high evapotranspiration. The hydraulic energy required to lift this water volume to a total dynamic head of 30 m was calculated assuming standard physical constants, with water density ρ=1000kg/m3 and gravitational acceleration g=9.81m/s2. The resulting daily power demand is approximately 572.25W, indicating the suitability of photovoltaic technology for irrigation in regions with abundant solar resources. The installed crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules exhibit an efficiency of approximately 17.1% under a reference irradiance of 1000W/m2, which aligns with the specifications of commercially available modules. This confirms that the selected modules perform close to their nominal efficiency under typical operating conditions. Considering the daily water demand, hydraulic head, average daily solar irradiation of 5kWh/m2·day, and overall system efficiency, the required peak power of the photovoltaic generator is estimated at approximately 1.78kW. This ensures reliable pump operation during the hottest month, when irrigation needs are at their maximum. From an environmental perspective, replacing a diesel-powered pump with the photovoltaic system results in a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Depending on the operating conditions and avoided fuel consumption, the system prevents approximately 1 to 3 tons of CO2 emissions per year. Additionally, solar pumping promotes controlled water abstraction, reduces soil degradation and salinization risks, especially in the coastal areas of Casamance, and eliminates the risk of hydrocarbon spills associated with diesel fuel use.

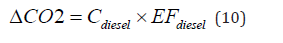

Overall, the results demonstrate that the photovoltaic pumping installation is technically feasible, environmentally sustainable, and well adapted to local agricultural practices. The combination of adequate water supply, reasonable energy demand, and significant environmental benefits confirms the relevance of solar-powered irrigation systems for small market gardening farms in southern Senegal and provides a strong basis for the subsequent economic analysis. Table 1 below summarizes the main characteristics, performance, and impacts of the photovoltaic pumping system installed for market gardening in Casamance. It includes technical parameters such as field area, pumped flow rate, total pumping height (including water source depth and tank height), hydraulic and PV power requirements, as well as daily pumped volumes and required power.

Table 1:PV pumping system overview.

Conclusion

The photovoltaic water pumping system for irrigation in Ziguinchor offers a sustainable alternative to diesel pumps, providing a reliable water supply while reducing fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. With a hydraulic power of 572.25W and a required PV generator power 1780W, it can pump approximately 49m3/day, or 7350m3/year. Economically, it becomes more costeffective than diesel after 2-4 years and can increase irrigation efficiency, improving crop yields and farmer income. Proper sizing, regular maintenance, and user training are essential to ensure optimal performance, while integration with smart irrigation techniques, expansion to community-based projects, and hybrid systems with energy storage could further optimize water use and enhance system autonomy during cloudy periods or night-time irrigation.

References

- Moussa MS, Bachirou D, Halidou I (2022) Assessing the performance of solar photovoltaic pumping system for rural area transformation in West Africa: Case of sekoukou village, Niger. In J Energy Power Eng 11(6): 114-124.

- Terang B, Baruah DC (2023) Techno-economic and environmental assessment of solar photovoltaic, diesel, and electric water pumps for irrigation in assam, India. Energy Policy 183: 113807.

- Rahman MM, Hasan S, Abid H, Uddin A, Adham AKM (2025) The utility of submersible solar irrigation pumps in accessing deeper groundwater for sustaining dry season rice cultivation in off-grid Bangladeshi haor areas. Clim Smart Agric 2(4): 100081.

- Glasnovic Z, Margeta J (2007) A model for optimal sizing of photovoltaic irrigation water pumping systems. Sol Energy 81(7): 904-916.

- Negera M, Dejen ZA, Melaku D, Tegegne D, Adamseged ME, et al. (2025) Agricultural productivity of solar pump and water harvesting irrigation technologies and their impacts on smallholder farmers’ income and food security: Evidence from Ethiopia. Sustainability 17(4): 1486.

- Gupta V, Singh SP (2025) Exploring the multiple dimensions of solar irrigation in south-Asian countries: Insights from a systematic review. Renew Energy Focus 54: 100711.

- Gupta E (2019) The impact of solar water pumps on energy-water-food nexus: Evidence from Rajasthan, India. Energy Policy 129: 598-609.

© 2026 Mamadou S. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)