- Submissions

Full Text

Aspects in Mining & Mineral Science

Welding of Exotic Materials

Calik A1*, Ucar N2 and Özdemir AF2

11Faculty of Technology, Isparta University of Applied Sciences, Turkey

22Faculty of Engineering and Natural Sciences, Department of Physics, Süleyman Demirel University, Turkey

*Corresponding author:Calik A, Faculty of Technology, Mechanical Engineering, Isparta University of Applied Sciences, 32260, Isparta, Turkey

Submission: November 14, 2025: Published: December 15, 2025

ISSN 2578-0255Volume14 Issue 4

Abstract

Exotic materials are high-performance alloys of stainless steel, aluminum, nickel, titanium, magnesium and copper. Hastelloy C-276 (UNS N10276) is known as an exotic material and is a nickel-chromium-molybdenum alloy with very high corrosion resistance to many chemical environments. In this study, the weldability of Hastelloy C-276/Hastelloy C-276 alloys welded with Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW) and the microstructure properties resulting from welding were investigated. Welding process was performed using ERNiCrMo-4 welding filler wire and argon gas protection. The results showed that the welded materials did not have any defects or discontinuities and had high quality welding materials. Compared to the base metal, an approximately 21% increase in the ultimate tensile strength and a 32% increase in yield strength of the welded samples were obtained. These improvements were attributed to the formation of cellular, columnar, and equiaxed dendrites in the microstructure after welding.

Keywords:Hastelloy C-276; Gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW); Welding; Microstructure; ERNiCrMo-4

Introduction

The development of advanced engineering applications in the aerospace, nuclear, chemical, and marine industries has increased the use of exotic materials such as titanium alloys, nickel-based super alloys, zirconium alloys, and high-entropy alloys [1-5]. These materials are often selected for their superior properties, including a high strength-to-weight ratio, exceptional corrosion resistance, and excellent performance at elevated temperatures [6-9]. However, welding such exotic materials remains a significant challenge due to their unique metallurgical behaviors, susceptibility to cracking, and complex microstructural transformations during thermal cycles. Correspondingly, it has been shown that during welding, the high temperatures and rapid cooling conditions can lead to phenomena such as dendritic solidification, micro segregation of alloying elements, and secondary phase precipitation in the fusion zone [10]. In addition, in the Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ), grain growth, carbide precipitation (M₆C, M₂₃C₆), and occasionally μ-phase formation may occur [11]. Such microstructural transformations can directly affect not only the mechanical properties of the alloy but also its most important advantage, namely, corrosion resistance. Understanding the microstructure of welded joints is critical, as it directly affects the mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, and long-term service reliability of components [12-15]. Factors such as solidification patterns, grain boundary evolution, precipitation, phase transformations, and residual stress distribution must be carefully analyzed.

Advanced welding techniques such as electron beam welding, laser welding, and friction stir welding are increasingly employed to control these microstructural features and minimize defects [16]. Recently, many studies have aimed to provide insights into the microstructural characteristics of welded exotic materials, highlighting the challenges, mechanisms of microstructural evolution, and their correlation with material performance [17-19]. By understanding these aspects, more reliable and efficient welding procedures can be developed for high-demand industrial applications. In this study, the weldability of Hastelloy C-276/Hastelloy C-276 alloys by manual Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW), the tensile and microstructure properties resulting from welding were investigated.

Experimental Methods

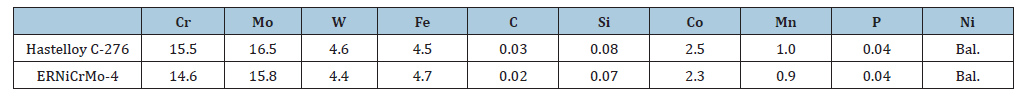

Hastelloy C-276 used in this study is a tungsten-added Ni-Cr- Mo super alloy. The chemical composition of Hastelloy C-276 is shown in Table 1. Welding process of two similar Hastelloy C-276 alloys was carried out using the gas tungsten arc welding (GTAW) method. The welding parameters were set as follows: current of 125A, voltage of 30V, welding speed of 5x10-3 m/s, gas flow rate of 0.09m3/s, and heat input of 0.90kJ/mm. The materials prepared in 0.25m x 0.00635m x 0.002m dimensions were subjected to a welding process with ERNiCrMo-4 welding wire having a 2.4mm diameter. It is well known that the most commonly used standard for GTAW is 99.996% pure argon. Since we know that higher purity provides better weld quality, we chose to use 99.9999% purity argon for GTAW welding in this study. In addition, since it is known from our previous studies that a 35° bevel angle creates a more efficient and solid weld, welding was carried out at approximately the same angle. Heat input (Q) for GMAW welding was calculated according to general recommendation, and it is based on arithmetic mean power [20].

After welding processes, the welded materials were cleaned and etched with appropriate solutions for microanalysis. Tensile tests welded samples prepared according to the standards given in the literature were also carried out in accordance with the standards given in the literature. These tests were performed using an MTS Landmark machine developing a force of 100kN (ASTM E8/E8M). The microstructure of the samples was examined using a PRIOR optical microscope.

Result and Discussion

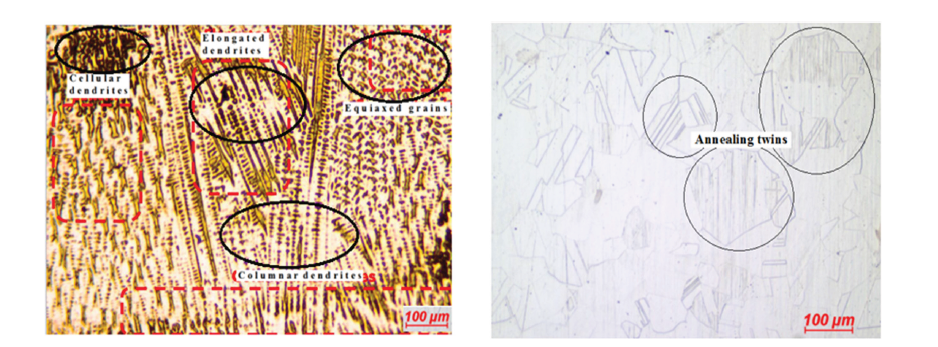

After the welding process using ERNiCrMo-4 welding filler wire and argon gas protection, it was observed that the welded similar Hastelloy C-276 alloys did not have any defects or discontinuities and had high welding quality. In addition, microstructure analyses, features such as dendritic structures, grain boundaries and annealing twins are thought to play a critical role in increasing the mechanical strength of the material and providing ductility [21,22], (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Microstructure image for weld metal of the welding of Hastelloy C-276 alloys with ERNiCrMo-4 filler wire.

Cellular dendrites, which form in regions where solidification begins rapidly, have a cell-like appearance and are generally seen in small temperature gradients or high cooling rates, while elongated dendrites grow parallel to the cooling direction. On the other hand, columnar dendrites are long, columnar structures with distinct orientations and generally form in regions where heat transfer from the melt is intense. They are important for strength because they cause mechanical anisotropy. The equiaxed grains, on the other hand, are small, randomly oriented crystals. They typically form by new nucleation within the residual melt toward the end of solidification and provide isotropy in mechanical properties (similar properties in all directions). As a result, different morphologies were formed in different regions during the solidification process in the weld zone, and the solidification conditions (cooling rate, temperature gradient, melt flow) seriously affected the microstructure. These different morphologies in the structure (dendritic regions, equiaxed grains, etc.) are known as normal microstructural features that result from the solidification conditions during weld formation. Similar results were also found in [23,24]. On the other hand, in Hastelloy C-276 welds, high temperatures and improper heat treatment conditions can lead to adverse events such as carbide formation and decomposition, particularly in the weld zone. However, no such adverse events were observed in this study. This is probably due to factors such as the argon shielding gas used in GTAW, the alloy’s low carbon content, high nickel and molybdenum content, short-term thermal effect of the welding process and high-speed cooling. Additionally, when we examine the image obtained from the weld area, we see that there are no voids, porosity, cracks, or foreign phase inclusions that could be considered defects. In summary, no defects or discontinuities other than solidification morphologies were observed in the weld.

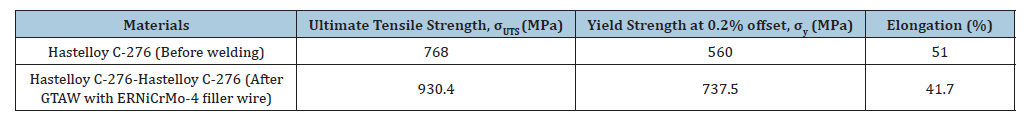

Tensile tests were applied to the welded specimens to verify that the welds were fully formed and could be used appropriately where necessary. The results are shown in Table 1. Table 2 shows a significant increase in tensile strength after welding (~21%). This result indicates that the weld metal and heat-affected zone have higher strength. In other words, the weld metal formed with the ERNiCrMo-4 filler wire has a harder structure. In addition, yield strength increased by approximately 32%. This means the weld zone can carry higher loads before starting to deform. We believe this may be related to precipitates, grain size reduction, or the distribution of alloying elements in the microstructure during welding. On the other hand, ductility decreased by approximately 18% after welding, which is expected. Increased strength often leads to a decrease in ductility (there is generally an inverse relationship between strength and ductility). In other words, the material became stronger but more brittle after welding.

Table 1:Chemical composition (wt %) of Hastelloy C-276 and welding wire.

Table 2:Tensile values of the structure obtained by welding two similar Hastelloy C-276 with method GTAW and without welding.

Conclusion

In this study, the weldability of Hastelloy C-276/Hastelloy C-276 alloys with GTAW welding method was studied. The general results obtained are expressed below:

a. The results demonstrated that the alloy exhibits excellent

weldability, as no defects such as porosity, cracking, or

inclusions were detected in the weld region.

b. Microstructural analyses revealed a complex solidification

structure consisting of cellular, columnar, and equiaxed

dendrites, which collectively contributed to the strengthening

of the weld metal.

c. Mechanical testing confirmed a substantial improvement in

performance after welding, with increases of approximately

21% in ultimate tensile strength and 32% in yield strength

compared to the base metal.

d. Although a moderate decrease in ductility was observed, no

embrittlement-related phases or micro cracks were detected,

indicating that the enhanced strength did not compromise the

structural integrity of the joint.

e. Overall, the findings indicate that GTAW with ERNiCrMo-4

filler metal provides a reliable and effective welding method

for Hastelloy C-276, producing joints with superior strength

and sound microstructural stability suitable for demanding

industrial applications.

References

- Peters M, Kumpfert J, Ward CH, Leyens C (2003) Titanium alloys for applications. Advanced Engineering Materials 5(6): 419-427.

- Hemphill MA, Yuan T, Wang GY, Yeh JW, Tsai CW, et al. (2012) Fatigue behavior of A5CoCrCuFeNi high entropy alloys. Acta Materialia 60(16): 5723-5734.

- Mathew MD, Nandakumar K (2017) Advanced materials for aerospace, nuclear, and chemical industries. Materials Today: Proceedings 4(2): 3192-3201.

- Jasim AH, Al-Khafaji Z, Radhi NS (2024) Review on improvement of the turbine oxidation and hot resistant against corrosion by nickel-based superalloy. Material and Mechanical Engineering Technology 4: 88-104.

- Gemci A, Şirin E, Kıvak T (2025) Effects of Al2O3 based nanofluids with different particle sizes on machining performance in milling of hastelloy X superalloy. Mateca 6(1): 52-62.

- Chen Y, Rong P, Fang X, Liu Y, Wu Y, et al. (2025) Effects of Al/Ti additions on the corrosion behavior of laser-cladded hastelloy C276 coatings. Coatings 15(6): 678.

- Park S, Ayten F, Bulutsuz G, Gokcekaya O, İlgazi ME, et al. (2025) Wear and corrosion performance of textured Hastelloy-X fabricated by laser powder bed fusion: Process window and microstructural features. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 39: 6156-6168.

- Burande SW, Bhope DV (2021) Review on material selection, tailoring of material properties and ageing of composites with special reference to applicability in automotive suspension. Materials Today: Proceedings 45(1): 520-527.

- Singh VB, Gupta A (2001) The electrochemical corrosion and passivation behavior of Monel 400 in concentrated acids and their mixtures. Journal of Material Science 36: 1433-1442.

- Ventrella VA, Berrettab JR, de Rossi W (2012) Pulsed Nd:YAG laser welding of Ni-alloy Hastelloy C-276 Foils. Physics Procedia 39: 569-576.

- Xudong WW, Zhong Y, Liu P (2023) Effect of precipitation behaviour of μ phase and M23C6 carbide on microstructure and creep properties of DD5 single-crystal superalloy during long-term thermal exposure. Materials at High Temperatures 40(3): 250-258.

- Huang S, Wang T, Miao J, Chen X, Zhang G, et al. (2024) Microstructure and high-temperature mechanical properties of a superalloy joint deposited with CoCrMo and CoCrW welding wires. Coatings 14(7): 892.

- Kangazian J, Kim HS (2025) Additive manufacturing of hastelloy X Ni-based alloy: Current trends, challenges, and perspectives. Metals and Materials Internationals.

- Wang Y, Liu P, Fan H, Guo X, Wan F (2023) Microstructure and mechanical properties of thick 08Cr9W3Co3VNbCuBN heat-resistant steel welded joint by TIP TIG welding. Materials Research 26: e20220370.

- Łastowska O, Jurczak W, Starosta R (2025) Influence of surface quality on corrosion resistance of stainless steel and aluminum alloy butt welds after innovative finishing. Scientific Reports 15: 27576.

- Shravan CN, Radhika NH, Kumar D, Sivasailam B (2024) A review on welding techniques: Properties, characterisation and engineering applications. Advanced Materials and Processing Technologies 10(2): 1126-1181.

- Singh A, Singh V, Singh AP, Ashutosh S, Patel D (2023) Welding investigations on mechanical property and microstructure of TIG and A-TIG Weld of Hastelloy C-276. Engineering Research Express 5(2):

- Bezawada S, Gajjela R (2023) Microstructural and mechanical characterization of welded joints between stainless steel and hastelloy made using pulsed current gas tungsten arc welding. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 32: 1076-1088.

- Tumer M (2021) Microstructure, mechanical and corrosion properties of TIG welded Hastelloy C-276. Materials Testing 62(9): 883-887.

- Bosworth M (1991) Effective heat input in pulsed current gas metal arc welding with solid wire electrodes. Welding Journal 70(5): 111-117.

- Gao Y, Ding Y, Chen J, Xu J, Ma Y, et al. (2019) Effect of twin boundaries on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Inconel 625 alloy. Materials Science and Engineering A 767:

- Deng Q, Miao Y, Yang Z, Zhao Y, Liu J, et al. (2025) Orientation, dendrites and precipitates in Hastelloy C276 alloy fabricated by laser and arc hybrid additive manufacturing. Journal of Materials Research and Technology 35: 3129-3143.

- Hu YN, Wu SC, Chen L (2019) Review on failure behaviors of fusion welded high-strength Al alloys due to fine equiaxed zone. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 208(1): 45-71.

- Derbiszewski B, Obraniak A, Rylski A, Siczek K and Wozniak M (2024) Studies on the quality of joints and phenomena therein for welded automotive components made of aluminum alloy-a review. Coatings 14 (5): 601.

© 2025 Calik A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)