- Submissions

Full Text

Associative Journal of Health Sciences

Discriminating Kidney Transplant Recipients Under Treatment in Two Groups of Health Care Providers in Respect of their Sociodemographic Characteristics

Amina Ahmed Belal* and KC Bhuiyan

1Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia

2Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author:Amina Ahmed Belal, School of Mathematical Sciences (Statistics), Faculty of Science and Technology, Universiti Kebangsaan, Malaysia

Submission: November 24, 2025;Published: January 26, 2026

ISSN:2690-9707 Volume4 Issue3

Abstract

This presentation was based on data collected from 409 patients of two geographical locations, viz. Klang Valley, and others in Malaysia. The patients were under treatment in two groups of public hospitals. In one group there were 4 hospitals under the Ministry of health (MOH) and in another group, there were 2 hospitals under the Ministry of education (MOE). The number of investigated patients from the first group of hospitals was 287. The remaining investigated patients were from hospitals under the Ministry of Education. The percentage of patients from Klang Valley was 72.4. The preference of hospitals was significantly associated with patients of two locations. Marital status of patients and their choice of hospitals were significantly associated. Preference of hospitals was also significantly associated with each of household income, catastrophic health expenditure, physical preparedness, financial preparedness, appointment compliance, duration of dialysis, and duration of kidney transplantation. Out of these variables, the most important variable in discriminating patients of two groups of hospitals was catastrophic health expenditure followed by duration of dialysis, geographical location, financial preparedness, household income and some other variables. This phenomenon was noted from the results of discriminant analysis.

Keywords: Discriminant Analysis; Health care providers; Geographical location; Kidney transplant recipients; Transplant centre; Risk ratio; Sociodemographic characteristics

Abbreviations: ESKD: End Stage Kidney Diseases; MOH: Ministry of Health; KTRs: Kidney Transplant Recipients; CHE: Catastrophic Health Expenditure

Introduction

Long term suffering from diabetes is the single most responsible factor to lead end stage kidney diseases (ESKD) of human beings. At this stage the kidney gradually fails in filtering the waste and excess liquid from the body as kidneys are functioning less than 15% of their normal capacity [1-8]. In this situation the alternative way for functioning of kidneys is renal replacement strategies. Today several renal replacement procedures are followed, including the main 3: haemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis or kidney transplantation [9-16]. But it was observed that the outcome of the dialysis therapy resulted poor survival rate, hence the better kidney replacement therapy is kidney transplantation which aims to improve the quality of life of ESKD patients in addition to their longer life span [17-21]. The success rate of kidney replacement therapy is higher, with over 95% of transplanted kidneys functioning well for one year, but long-term success and survival of recipients is not unquestionable [22-29]. The problem arises if the recipients have chance of comorbidity, and there are no network and scope of organ sharing data base [30-33]. Beside these, the other problems are over age of patients, education, employment, economy, medication facilities, and other sociodemographic factors [34-43]. In this paper, an attempt was made to investigate the impact of sociodemographic characteristics on kidney transplant recipients treated in two health care providers.

Methodology

The paper was prepared analysing the secondary data collected from internet which was recorded in February and June 2018 by a team of researchers headed by Peter Gan Kim Soon who collected the data himself [44,45]. The investigation was done in six public hospitals providing post- transplantation care in the Klang Valley, Malysia. The government hospitals are under the Ministry of Health (MOH) and are university hospitals under the Ministry of Education (MOE). The study location is most densely populated, and it is industrialised area. The selected hospitals provide posttransplantation care to nearly half of the patients depending on kidney replacement therapy and the patients were kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) [46].

The information was recorded from 409 KTRs of six selected public hospitals. The Kidney transplant recipients were Malaysian adults of 18 years and above. These adults had the capacity to understand either Malay, or English, or Chinese, and were capable to understand the questionnaire by themselves [45]. During the survey, pretested questionnaire was used to collect data. Each questionnaire was so designed to collect information on sociodemographic aspects of any of the patients under investigation. Except sociodemographic characteristics the other questions were on health conditions during survey period and the conditions prior to 4 weeks of the survey period. The collected data were on education (None/Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary), marital status, employment status (Employed, Outside workforce, and Unemployed), geographical location (Klang valley, and others), health care provider (MOH and MOE), transplant duration (in months), dialysis duration (in months), transplant centre (Local ,and overseas), transplant type (Living and Deceased), physical preparedness, emotional preparedness, spiritual preparedness, financial preparedness, appointment compliance, medication compliance, household income (<US$ 1085.39= 1= bottom 40%, US$ 1085.39- < US$ 2394.57=2= middle 40%, and > US$ 2394.57=3= top 20%), catastrophic health expenditure [ CHE; 45,47-50]. All the above-mentioned variables were qualitative in nature, and these were measured in nominal scale. The data on transplant duration and dialysis duration were measured months and these were also presented in classes.

The association of the variables with health care provider was studied including the measure of risk ratio in choosing a health care provider [51,52]. The investigated units were discriminated by their choice of health care provider using discriminant analysis [53-56] which helped in identifying the most important variables for discrimination of two groups of patients treated in two different health care providers.

Result

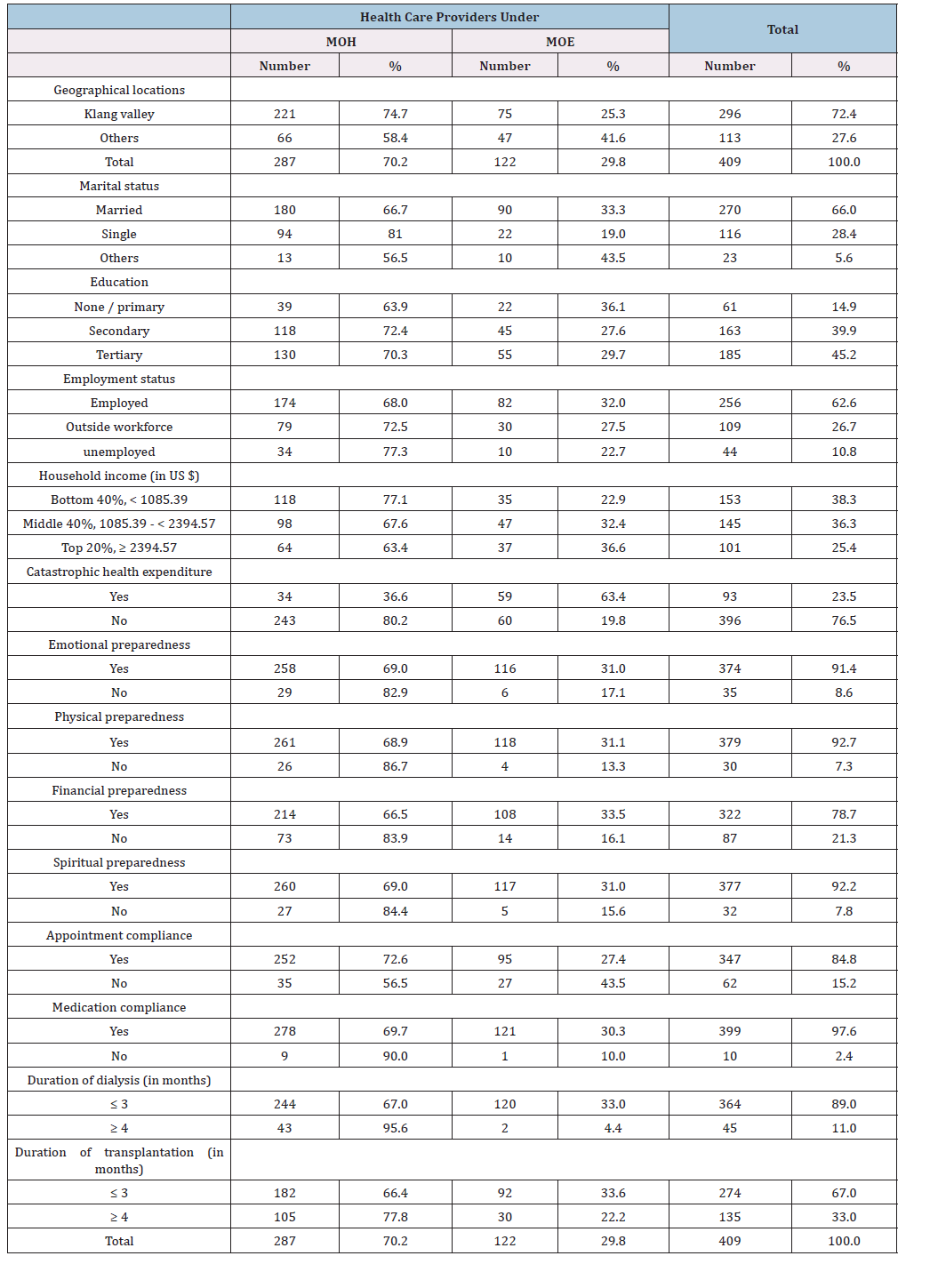

Out of 409 investigating units, 287 units were under treatment in hospitals under Ministry of Health (MOH), and the remaining 122 were under treatment in hospitals under Ministry of Education (MOE). These transplant recipients were from two geographical locations, viz. Klang Valley and others. The patients from Klang Valley were 72.4% and 74.7 % of them were under treatment in hospitals under MOH. The percentage of patients treated in hospitals under MOH from other location was 58.4. This differential in percentages of patients of two locations treated in health care providers under MOH was significant [ X2 = 10.324, p-value=0.001]. The recipients of Klang Valley were 28% more prone to prefer treatment in health care providers under MOH [ R.R.= 1.28, C.I. (1.08, 1.52)]. A big group of recipients (66.0%) were married, and 66.7% of them were patients in hospitals under MOH. Percentage of single recipients was 28.4; 81% of them were patients in health care providers under MOH. The single recipients were 22% more likely to be admitted into hospitals under MOH [ R.R.=1.22, C.I. (1.08, 1.38)]. The proportions of admitted patients of different marital status into two health care providers were significantly different [ X2 = 10.172, p- value = 0.006]. A big group of recipients had tertiary level education; 70.3% of them were under treatment in hospitals under MOH. The next bigger group of recipients (39.9%) had secondary level education and 72.4% of them were under treatment in health care providers under MOH. However, the proportions of patients of different levels of education admitted into different health care providers were not significantly different [X2 = 1.519, p-value= 0.468]. A big group of recipients (62.6%) were employed and 68.0% of them were admitted in hospitals under MOH. Unemployed patients were only 10.8%, but a bigger group of those patients (77.3%) were admitted in hospitals under MOH. Hospitals under MOH were also preferred by most (72.5%) of the patients who were outside workforce (26.7%). However, preference of hospitals by different levels of workforce was independent [X2 = 1.930, p-value = 0.381] (Table 1).

Table 1:Distribution of kidney transplant recipients under treatment in two health care providers according to their sociodemographic characteristics.

Choice of health care providers was significantly associated with level of income of the kidney transplant recipients [X2 = 6.232, p-value = 0.044]. There were 38.3% recipients who had bottom level monthly income of less than US$ 1085.39 and 77.1% of them preferred treatment in hospitals under MOH.

Their preference was 17% more than the preference of other recipients having more income [R.R= 1.17, C.I. (1.03, 1.33)]. Recipients of top- level income (≥ US $ 2394.57) were 25.3% and 63.4% of them preferred health care provider under MOH. This percentage was lowest compared to the similar percentage of recipients of other levels of income. The percentage of recipients who had no catastrophic health expenditure was 76.5 and 80.2% of them preferred treatment in hospitals under MOH. Their preference was 119% more compared to the preference of recipients experienced of catastrophic health expenditure [ R.R.=2.19, C.I. (1.92, 2.88)]. The choice of health care providers was significantly associated with the experience of catastrophic health expenditure [ X2 = 64.468, p-value = 0.000]. Only 21.3% recipients were not financially prepared and 83.9% of them preferred treatment in hospitals under MOH. Their choice was 26% more compared to the choice of financially prepared recipients [R.R.=1.26. C.I. (1.12, 1.42)]. The choice of health care providers was significantly associated with financial preparedness [X2 = 9.963, p-value = 0.002].

The percentage of physically prepared recipients was 92.7 and 68.9% of them preferred treatment in health care providers under MOH against the corresponding percentage 86.7 of recipients who were not financially prepared. The preference of this letter group of recipients was 26% more compared to the preference of other recipients [R.R.=1.26, C.I. (1.08, 1.47)]. Preference of health care provider was significantly associated with physical preparedness [X2 = 4.209, p-value = 0.040]. Emotional preparedness was noted among 91.4% recipients, and 69.0% of them were admitted into hospitals under MOH. A higher percentage (82.9%) of recipients without emotional preparedness preferred hospitals under MOH. But this differential in proportions of preference of health care providers was not significant [X2 =2.943, p-value= 0.086]. The percentage of spiritual prepared recipients was 92.2 and 69.0% of them preferred treatment in hospitals under MOH. The corresponding percentage of preference of hospitals by recipients who were not spiritual prepared was 84.4. But these two proportions of preference of hospitals under MOH were not significantly different [X2 = 3.346, p-value=0.067].

Appointment compliance was noted among 84.8% kidney transplant recipients; among them 72.6% were treated in hospitals under MOH. This percentage of recipients was significantly higher compared to the percentage (56.5%) of recipients who did not comply with appointment compliance [X2 = 6.572, p-value= 0.010]. Appointment compliance was a factor for choice of hospitals under MOH by 29% more recipients compared to their counterpart [R.R.=1.29, C.I. (1.03, 1.62)]. Very few patients (2.4%) were ignorant of medical compliance, but higher portion (90.0%) of them preferred treatment in hospitals under MOH, on the other hand, 67.6% recipients had positive attitude towards medical compliance. However, choice of hospitals was independent of medical compliance [ X2 = 1.926, p-value= 0.392].

Duration of dialysis for 3 months and less was continuing among 89.0% recipients. Among them 67.0% preferred treatment in hospitals under MOH. The corresponding percentage of preference was noted among 95.6% recipients who were experienced of duration of dialysis for 4 months and more. These two percentages of choice of hospitals were significantly different [X2 =15.566, p-value=0.000]. The preference of treatment in hospitals under MOH was noted among more 43% recipients [ R.R.=1.43, C.I. (1.30, 1.57)]. Transplant duration and preference of health care provider were significantly associated [X2 =5.571, p-value=0.018]. The percentage of recipients for whom transplant duration was 4 months and above was 33.0%. Among them 77.8% preferred treatment in hospitals under MOH. The preference of hospitals under MOH was made by 17% more recipients of this category [ R.R.= 1.17, C.I. (1.03, 1.32)].

Results of discriminant analysis

From the results presented above, it was noted that the preference of health care providers was not independent of some of the individual sociodemographic characteristics. Differential attitudes were observed in choosing a hospital. This attitude was noted in observing the association of preference of health care provider with each of the sociodemographic variables.

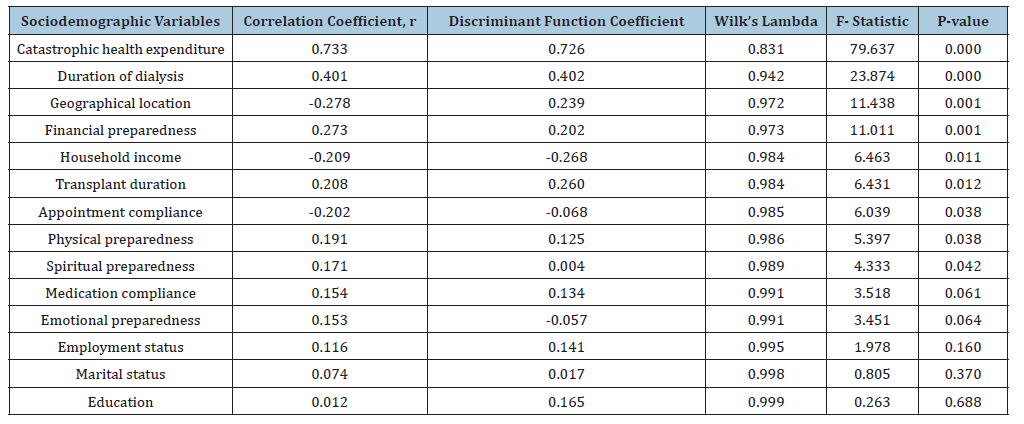

To identify the most responsible variable in choosing a hospital, discriminant analysis was done. The variables included in discriminant analysis were geographical location, marital status, education, employment status, household income, catastrophic health expenditure, financial preparedness, appointment compliance, medication compliance, physical preparedness, spiritual preparedness, emotional preparedness, duration of dialysis, and duration of transplantation. The initial result of the analysis indicated that the two groups of transplant recipients treated in two health care providers were significantly different [X2 Wilk’s Lamda=0.725, X2 = 123.377, p-value=0.000].

The other results were shown in Table 2. It was seen that the highest correlation coefficient (r) was 0.733. It was for the variable catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) with discriminant function score. This result indicated that CHE was the most responsible variable to discriminate the patients group treated in hospitals under MOH from other patients group treated in hospitals under MOE [55, 56]. Accordingly, the next important variable for discrimination was duration of dialysis followed by geographical location, financial preparedness, household income, transplant duration, appointment compliance, physical preparedness, and spiritual preparedness.

Table 2:Results of discriminant analysis.

Discussion

The study was conducted in two geographical locations viz. Klang Valley and others in Malaysia. The analysis was done using the data collected from 409 patients who were under treatment in two groups of health care providers. One group of health care providers was under MOH, and another group was under MOE. In the first group the number patients under treatment were 287 and the remaining 122 patients were under treatment in second group of health care providers under MOE. From the analytical results, it was found that the choice of health care providers was significantly associated with geographical locations, where more patients of Klang Valley preferred hospitals under MOH. More single adults and more patients who were conscious about appointment compliance preferred health care providers run by MOH. These group of health care providers were also chosen by more transplant recipients who had no physical preparedness, financial preparedness, and who were in the bottom 40% low household income group. Longer duration of dialysis and longer duration of kidney transplantation were also the causes of preference of Hospitals under MOH.

The transplant recipients treated in two groups of health care providers were significantly different in choosing the hospitals in respect of their sociodemographic variables, viz. catastrophic health expenditure, duration of dialysis, geographical location, financial preparedness, household income, transplant duration, appointment compliance, physical preparedness and spiritual preparedness. This fact was noted from the results of discriminant analysis.

Conclusion

The information presented in this paper was based on data collected from 409 kidney transplant recipients of Malaysia. Most of them (296) were from Klang Valley and the remaining 113 were from other geographical location. The percentage of recipients who preferred health care providers under MOH was 70.2. The remaining 29.8% recipients preferred health care providers under MOE. Preference of health care providers under MOH by recipients of Klang Valley was 28% more compared to the preference of other recipients. Higher level of preference (22.0%) was also noted by the single recipients compared to the preference of married and other recipients. Highest percentage (45.2%) of respondents had tertiary level education, but choice of hospital did not depend on level of education. Similar independence was also observed in studying the association of choice of health care provider and employment status. Both household income and catastrophic health expenditure were significantly associated with preference of health care provider. More people of lower income group preferred hospitals under MOH. The percentage of recipients who had no catastrophic health expenditure was 76.5 and higher proportion (80.2%) of them preferred health care providers under MOH. Choice of health care provider was significantly associated with financial preparedness of recipients. Only 21.3% recipients were not financially prepared and majority (83.9%) of them preferred hospitals under MOH.

Most of the kidney transplant recipients were physically (92.7%), emotionally (91.4%) and spiritually (92.2%) prepared for treatment. Only 7.3% recipients were not physically prepared for treatment, but majority (86.7%) of them preferred health care providers under MOH. Emotional preparedness and spiritual preparedness had no influence in preferring the health care provider. Appointment compliance and medical compliance was noted among majority of the recipients, but medical compliance was not associated with the choice of health care provider. The preference of health care provider was significantly associated with both dialysis and transplant duration. Discriminant analysis showed that the most responsible variable in discriminating the two groups of recipients treated in two types of health care providers was catastrophic health expenditure followed by duration of dialysis, geographical location, financial preparedness, household income etc.

Diabetes is one of the most influencing causes of kidney disease and at one stage diabetic patients reach the stage of renal failure condition and they need dialysis for their survival. As an alternative treatment of dialysis kidney transplantation can be done if it is possible. But rate of success of dialysis and / or kidney transplantation may be increased if proper post- transplantation care is done. For this research and training of the related staffs are needed. However, the situation can be improved if people are encouraged to maintain the healthy life so that they can control the sugar level, especially when their age is increasing. Government and social workers can do a lot to improve situation towards healthy life in the society.

Acknowledgement

The author (s) would like to thank the researchers who made their data publicly available.

Competing Interest

The author(s) declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Stein G, Funfstuck R, Schiel R (2004) Diabetes mellitus and dialysis. Minerva Urol Nefrol 56(3): 289-303.

- Hoogeveen EK (2022) The epidemiology of diabetic kidney disease. Kidney Dial 2(3): 433-442.

- Farah RI, Al-Sabbagh MQ, Mamani MS, Albtoosh A, Arabiat M, et al. (2021) Diabetic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrology 22(1) 223.

- Chen Y, Lee K, Ni Z, He JC (2020) Diabetic kidney disease: challenges, advances, and opportunities. Kidney Disease 6(4): 215-225.

- Hussain S, Jamali MC, Habib A, Hussain Md S, Akhtar M, et al. (2021) Diabetic kidney disease: An overview of prevalence, risk factors, and biomarkers. Clin Epide & Global Health 9: 2-6.

- Sinha SK, Nicholas SB (2023) Pathomechanisms of diabetic kidney disease. Jour Clin Med 12(23): 7349.

- Lucas B, Taal MW (2019) Epidemiology and causes of chronic kidney disease. Medicine 51(3): 165-169.

- Bhuyan KC (2020) Identification of socioeconomic variables responsible for diabetic kidney disease among Bangladeshi adults. Biomed J Sci & Tech Rep MS. ID. 004021: 18092-18098.

- Mousu GG, Fararouei M, Seif M, Maryam P (2022) Chronic kidney disease and its health related factors: A case-control study. BMC Nephrology 23(1): 24.

- Li H, Lu W, Wang A, Jiang H, Lyu J (2021) Changing epidemiology of chronic kidney disease as a result of type 2 diabetes mellitus from 1990 to 2017 estimates from global burden of disease 2017. J Diabetes Investig 12(3): 346-356.

- Fraser SDS, Roderick PJ (2019) Kidney disease in the global burden of disease study 2017. Nat Rev Nephrol 15(4): 193-194.

- Zhang L, Long J, Jiang W, Shi Y, Xiangxing He, et al. (2016) Trends in chronic kidney disease in China. N Engl J Med 375: 905-906.

- ASN (2024) Advancing kidney health worldwide, American Society of Nephrology.

- Francis A, Harhay MN, Ong ACM, Tummalapalli SL, Ortiz A, et al. (2024) Chronic kidney disease and the global health agenda: An international consensus. Net Review Nephrol 20(7): 473-485.

- Chanrong K, Liang J, Liu M, Liu S, Wang C (2022) Burden of chronic disease and its risk attributable burden in 137 low-and- middle income countries, 1990-2019: Results from global burden of disease study, 2019. BMC Nephrology 23(1): 17.

- Hakim RM, Lazarus JM (1995) Initiation of dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 6(5): 1319-1328.

- Trevino-Becerra A (2009) Substitute treatment and replacement in chronic kidney disease: Peritoneal dialysis, haemodialysis, and transplant. Cir Cir 77(5): 411-415.

- Andre M, Huang F, Everly M, Bunnapradist S (2014) The UNOS renal transplant registry: Review of the last decade. Clinical Transplant pp: 1-12.

- Hooi LS, Bavanandan S, Ahmad G, Lim YN, Bee BC, et al. (2021) Nephrology in Malaysia. Neprology Worldwide, Springer International Publishing, pp: 361- 375.

- Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Knoll G, Bello A, Browne S, et al. (2011) Systematic review: Kidney transplantation, compared with dialysis in clinically relevant outcomes. Am J Transplant 11(10): 2093-2109.

- Seng WH, Leong GB (2015) 23rd Report of the Malaysian Dialysis and Transplant Register, Malaysian Society of Nephrology, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

- Berkoben M, Schwab S (1999) Dialysis or transplantation: Fitting the treatment to the patient. Annu Rev Med 50: 193-205.

- Swinski D, Poggio ED (2021) Introduction to kidney transplantation: Long-term management challenges. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 16(8): 1262-1263.

- Vijay K, Manisha S, Pranav K Jha (2024) Kidney transplantation in India - past, present, and future. Indian Journal of Nephrology.

- Suthanthiram M, Strom TB (1994) Renal transplantation, N Eng J Med 331(6): 365-376.

- Shogik A, Hanlon M (2023) Kidney transplantation, Stat Pearls [Internet].

- Hasmi S, Poommipanit N, Kahwaji J, Bunnapradist S (2007) Overview of renal transplantation. Minerva Med 98(6): 713-729.

- Jun H, Hwang JW (2022) The most influential articles on kidney transplantation: A PRISMA- compliant bibliometric and visualized analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 101(3): e28614.

- Augustine J (2018) Kidney transplant: New opportunities and challenges. Cleveland Clin J Med 85(2): 138-144.

- Karuthu S, Blumberg Emily A (2012) Common infections in kidney transplant recipients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7(12): 2058-2070.

- Allison SJ (2024) Consequences of microvascular inflammation in transplantation. Nature Reviews Nephrology 21(1): 7.

- Kyla N, Seychelle Y, Graham S, Garg AX, Elliott L, et al. (2025) Variation in kidney transplant referral, living, donor contacts, waiting list and kidney transplant across regional programs in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cohort study, Can J Kidney Health Dis 12: 20543581251346048.

- Naylor KL, Dixon SN, Garg AX, Kim SJ, Blake PG, et al. (2017) Variation in access to kidney transplantation across renal programs in Ontario, Canada, Amer Jour of Transplantation 17(6): 1585-1593.

- Chapman JR (2013) What are the key challenges we face in kidney transplantation today? Transplant Res 2(1): S1.

- Mistretta A, Veroux M, Grosso G, Contarino F, Biondi M, et al. (2009) Role of socioeconomic conditions on outcome in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation Proceedings 41(4): 1162-1167.

- Goldfarb-Rumyantzeb AS, Koford JK, Baird BC, Madhukar C, Habib AN, et al. (2006) Role of socioeconomic status in kidney transplant outcomes. Clin Jour Amer Soc Nephrology 1(2): 313-322.

- Hod T, Goldfarb-Rumyantzeb AS (2014) The role of disparities and socioeconomic factors in access to kidney transplantation and its outcomes. Ren Fail 36(8): 1193-1199.

- Khial-Talantikite W, Viganeau C, Deguen S, Siebert M, Couchoud C, et al. (2016) Influence of socioeconomic inequalities on access to renal transplantation and survival patients with end-stage renal disease. Plos One 11(4): e0153431.

- Sehoon P, Jina P, Jihoon J, Yungoung J, Yong CK, et al. (2023) Changes in socioeconomic status and patient's outcome in kidney transplantation recipients in South Korea. Korean J Transplant 37(1): 29-40.

- Chisholm MA, Spivey CA, Van Nus A (2007) Influence of economic and demographic factors on quality of life in renal transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 21(2): 285-293.

- Irena B, Sajan K, Daniel R, Adnan S (2013) Socioeconomic deprivations are independently associated with mortality post kidney transplantation. Kidney Int 84(4): 803-809.

- Ye Zhang, Ulf-G Gerdtham, Helena R, Johan J (2018) Socioeconomic inequalities in the kidney transplantation process: A registry-based study in Sweden. Transplant Direct 4(2): e346.

- Tung-Ling C, Nai-Ching C, Chun-Hao Y, Ching-Chin L, Chien-Liang C (2024) The association of socioeconomic status on kidney transplant access and outcomes: A nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Nephrol 37(6): 1563-1575.

- 0284607.s001.xlsx.

- Kim Soon PG, Sanjoy R, kun Lim S, Su TT (2023) Effect of socioeconomic status and health care provider on post-transplantation care in Malaysia: A multi-centre survey of kidney transplant recipients. PLOS one 18(4): e0284607.

- MDTR Reports- NRR-National Renal Registry (2023) 31st Report of the Malaysian dialysis and transplant registry. Malaysian Society Nephrology.

- Wagstaff A, Gabriela F, Justine H, Marc-Francios S, Kateryna C, et al. (2018) Progress on catastrophic health spending in 188 countries: A retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health 6(2): e169-e179.

- Wang H, Torres LV, Travis P (2018) Financial protection analysis in eight countries in WHO South-East Asia Region. Bull World Health Organ 96(9): 610-620E.

- Xu K, Evans DB, Keik K. Riadh Z, Jan K, et al. (2003) Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multi-country analysis. Lancet 362(9378): 111-117.

- Jac WC, Tae HK, Jung SI, Suk YJ, Woo-Rim K, et al. (2016) Catastrophic health expenditure according to employment status in South Korea: A population-based panel study. BMJ Open 6(7): e011747.

- Bhuyan KC (2020) Introduction to Meta Analysis. Lap Lambert Academic Publishing.

- Bhuyan KC (2022) Risk factors for simultaneous prevalence of two non-communicable diseases in Bangladeshi males and females. Lambert Academic Publishing.

- McLachlan GJ (2004) Discriminant analysis and statistical pattern recognition, Wiley Inter-science.

- Garson GD (2008) Discriminant function analysis.

- Bhuyan KC (2019) A note on the application of discriminant analysis in medical research. Archives of Diabetes and Obesity 2(2): 142-146.

- Bhuyan KC (2004) Multivariate analysis and its applications. New Central Book Agency (P) Ltd, India.

© 2026 Amina Ahmed Belal. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)