- Submissions

Full Text

Advances in Complementary & Alternative medicine

The Role of Yoga Therapy Across Health Conditions: Insights from the Pañcamaya Framework and Tri Krama Model

Jennifer Vasquez1* and April C Bowie Viverette2

1School of Social Work, Texas State University, USA

2Department of Social Work, University of North Alabama, USA

*Corresponding author:Jennifer Vasquez, PhD, LCSW-S, Texas State University, 601 University Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666, USA

Submission: November 04, 2025;Published: November 14, 2025

ISSN: 2637-7802 Volume 9 Issue 1

Abstract

This study examines the impact of yoga therapy interventions on yoga therapists and their clients across various health conditions. It examines which conditions they address, what practices they use, and how they perceive change through the lens of the pañcamaya model, a traditional yogic framework describing five interconnected layers of human experience: structural (annamaya), physiology (prāṇamaya), mind (manomaya), personality (vijñānamaya), and emotions (ānandamaya). The tri krama model is applied to enhance the understanding of yoga therapy interventions for treating illness (Cikitsā krama), preventing illness (Rakṣaṇa krama), and developing capacities (Śikṣaṇa Krama). A convergent mixed-methods design was employed. A Qualtrics survey was distributed to certified yoga therapists through professional networks. Quantitative data included conditions treated and tools used (e.g., movement, breathwork, meditation). Thematic analysis was selected to identify recurring patterns in qualitative responses while preserving the depth of individual insights. Quantitative and qualitative data were integrated using a side-by-side joint display to examine relationships between practices and perceived effects. Findings suggest that therapists perceive yoga therapy interventions as promoting improvements in physiological symptoms, emotional well-being, mental clarity, and inner resilience, even in clients with chronic or terminal illness. Therapists’ perspectives highlight the multidimensional impact of yoga therapy on overall health. The pañcamaya model offers a valuable lens for understanding healing beyond symptom relief, supporting the integration of holistic frameworks into health research.

Keywords:Yoga therapy; Yoga therapist; Health; Healing; Pañcamaya model

Introduction

The way yoga views the human system is based upon traditional Indian ways of thinking about the body [1]. Yoga therapy is the intentional instruction of yogic practices and teachings to prevent and alleviate pain or suffering, tailored to a client’s specific condition and goals [2]. The primary distinction between a yoga practitioner and a therapeutic yoga practitioner is not the ability to utilize yoga techniques, but rather the understanding of how and when to apply them in a way that best suits the client’s needs [1]. Yoga therapy is a one-to-one therapeutic relationship in which the therapist designs an individualized practice for the client based upon the current state of their system, goals, and capacities. Meditation, breathwork, and physical movement are the primary tools of therapeutic yoga practice [3]. In yoga therapy, there is an emphasis on curating methods and techniques into a personalized practice that specifically targets the symptoms and needs of each client [1].

Literature Review

Yoga therapy

Yoga therapists work with clients to empower and guide them in a journey toward wellness by utilizing the methods and techniques of therapeutic yoga [3]. Therapists workcollaboratively with clients to support improved health and wellbeing through the creation of individualized yoga practices based on evidence informed therapeutic yoga techniques [3]. These practices are created through the intentional sequencing of breath, movement, and meditation to build a daily practice that supports the client’s needs and goals [3]. Three models have a significant influence in the yoga world: pañcamaya, prana vayus, and the model of subtle anatomies, which shape how the human system is viewed and how personalized treatments are created to coincide with this perspective of the human system [1]. Understanding the human system through these anatomies is vital for forming specific yoga practices that target the unique needs and symptoms of clients, bringing about healing and prosperity [1]. Yoga therapists observe, assess, establish goals, and design interventions to support healing in the therapeutic application of yoga, known as Cikitsā Krama.

They also prevent disease in the Rakṣaṇa Krama application of yoga therapy or help clients develop new capacities, expand their knowledge, and enhance their skills using Śikṣaṇa Krama. The yoga therapist assesses the needs of each client and based on the state of each client’s system, determines appropriate interventions. Speaking to his senior Western students, Mr. Desikachar, son and longtime student of Krishnamacharya, widely considered the father of modern yoga, explained appropriate application, “The teacher decides which of the Tri Krama is the best for the student: Śikṣaṇa Krama requires a perfect knowing to transmit a strict practice, without any compromise, as it should be in Vedic chanting, for example. Rakṣaṇa Krama is aimed at protection and preservation, promoting continuity at various levels, such as health, abilities, and knowledge. Cikitsā Krama looks for adaptation, healing, and recovery” [4].

Complementary health care

Yoga therapy is increasingly recognized as a valuable adjunct and complementary approach in diverse therapeutic contexts. For individuals recovering from substance use, yoga therapy offers a structured and supportive space for self-reflection and physical activity, effectively complementing traditional rehab programs [5]. It provides a tool to decompress from the intense rehab setting as well as other responsibilities outside of a treatment setting, such as parenting [5]. When tailored to address issues such as trauma, PTSD, anxiety, and depression, it becomes a more accessible intervention for communities that typically experience barriers to care [6]. In addition to its therapeutic potential for mental health, yoga therapy supports relational health by promoting mindfulness, self-compassion, and deeper social connectedness, thereby enhancing both intrapersonal and interpersonal relationships [7]. Evidence also supports the effectiveness of yoga not only as a complementary treatment but also as a stand-alone therapy for managing anxiety and depression [8]. This also applies in culturally specific contexts, where accessibility to conventional mental health care may be limited [8]. In a meta-analysis of twenty randomized controlled trials, yoga therapy interventions significantly improved self-reported PTSD symptoms and both immediate and long-term depression symptoms [9].

For patients diagnosed with PTSD, yoga can provide a safe and effective complementary treatment to reduce PTSD and depression symptoms [9]. Cramer et al. [10] conducted a systemic review and meta-analysis on the use of yoga in the treatment of anxiety and found evidence for small, short-term effects on anxiety and depression, and it was not associated with increased injuries. Strong short-term evidence was found that yoga reduces low back pain, back-specific disability, and global improvement in a systematic review and meta-analysis of ten randomized controlled trials with 967 chronic low back pain patients [11]. In a systemic review and meta-analysis of fourteen Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), yoga was found to be safe and well-accepted for mild to moderate Parkinson’s Disease, positively impacting physical and mental health, with similar or greater effects when compared to exercise [12]. In a three-month RCT of 124 women with type 2 Diabetes, Kumar and colleagues (2017) found yoga and peer support showed improvements in quality of life and glycemic outcomes compared to a control group with only peer support. Collectively, these findings highlight the holistic benefits of yoga therapy and its potential to bridge gaps in physical and mental healthcare services across diverse and underserved populations.

Methods

This study recruited yoga therapists from the International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) certified yoga therapy schools by circulating a flyer to the institute’s network of Yoga therapists. The research flyer was emailed to participants who could sign up to participate by completing a voluntary Qualtrics survey. The survey collected data on participants’ sociodemographics and characteristics, as well as their perceptions of therapeutic yoga interventions in relation to mental and physical health conditions. They were also asked about their perceived impact of therapeutic yoga interventions on the 5 pañcamaya domains, as well as questions about the application of the Tri Krama model, using a five-point Likert scale (1=not at all effective, 2=slightly effective, 3=moderately effective, 4=very effective, 5=extremely effective). The survey also inquired about their ratings of the impact of therapeutic yoga interventions (i.e., asana, pranayama, meditation, chanting, nyasa) on each of the five pañcamaya domains: Annamaya/physiology, Pranamaya/energy, Manomaya/mind, Vijnamaya/personality, and Anandamaya/feelings. Finally, they were asked about their perceived impact of these interventions on the following physical and mental health conditions: hypertension, diabetes types I, II, and pre-diabetes, cancer, back pain, headaches, arthritis, multiple sclerosis, asthma, obesity, menopause, stress, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder. Participants rated these perceptions based on axis point Likert scale (1=I did not treat this condition, 2=not at all effective, slightly effective, 3=moderately effective, 4=very effective, 5=extremely effective).

Data Analysis

There were some missing cases. We were able to impute them. The distribution of continuous data was normal. We excluded diabetes and MS conditions from the bivariate analysis because over half of the participants reported not having worked with these conditions. IBM SPSS version 29.0 was used to analyze the data, with statistical significance achieved at an alpha level of <.05. Participants were also asked open-ended questions about their experiences working with yoga therapy clients using the Tri Krama model to determine appropriate yoga interventions. For example, participants were asked to list yoga therapy goals related to the three traditional Tri Krama frameworks: cikitsā (healing), rakṣaṇa (thriving), śikṣaṇa (discovering). Qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis and NVivo15 software. The six steps of thematic analysis were adhered to including Phase 1: Familiarization with the data, Phase 2: Generating initial codes, Phase 3: Searching for themes, Phase 4: Reviewing themes, Phase 5: Defining and naming themes, and Phase 6: Producing the report [13]. During Phase 1, reflections were reviewed across all five pañcamaya dimensions.

Researchers noted language around physical outcomes, emotional shifts, energy awareness, mental clarity, and spiritual meaning. Memoing helped identify the different layers therapists perceived within client change. In Phase 2, initial codes were generated. For example, “Clients notice more calmness after breathing” was coded as ‘pranic calming’, “Deeper joy after emotional release” was coded as ‘emotional healing’, “Back pain improved significantly” was coded as ‘physical symptom relief’, “Clients understand themselves differently” was coded as ‘selfawareness’, and “Depression lifted after regular meditation” was coded as ‘emotional transformation’. During Phase 3, codes were grouped by pañcamaya dimension: Annamaya: Physical healing, symptom recovery, Prāṇamaya: Breath regulation, subtle energy awareness, Manomaya: Emotional regulation, stress reduction, Vijñānamaya: Identity, discernment, self-inquiry, and Ānandamaya: Joy, deeper meaning, emotional resilience. In Phase 4, data excerpts were checked against emerging themes. An example of the refinement in this phase is “Breath as an energetic bridge” combined with “calming anxiety through breathing” under ‘pranic regulation’ and “Finding purpose” and “deeper joy” grouped under ‘spiritual connection’.

Discrepant cases (e.g., lack of perceived change in asthma) were retained to inform divergence. In Phase 5. Themes were named and defined. The Annamaya theme is pain relief and functional healing, defined as improvements in physical symptoms and mobility. The Prāṇamaya theme is breath and energy regulation, defined as the use of prāṇāyāma and energetic practices for balance and calming. The Manomaya theme is emotional regulation and mental clarity, defined as reduction in stress, anxiety, and mental clutter. The Vijñānamaya theme is self-awareness and insight, defined as clients gain perspective on their patterns, values, and choices. The Ānandamaya theme is emotional joy and spiritual connection, defined as deeper states of joy, presence, and personal meaning. In Phase 6, themes were synthesized into the joint display under “Qualitative Themes” and “Integration Summary.” Interpretations linked qualitative insights to the statistically significant conditions per dimension (e.g., prāṇamaya and PTSD, ānandamaya and depression). The final table supports meta-inferences in the discussion about where therapist insight and statistical significance converged or diverged.

Results

Quantitative strand

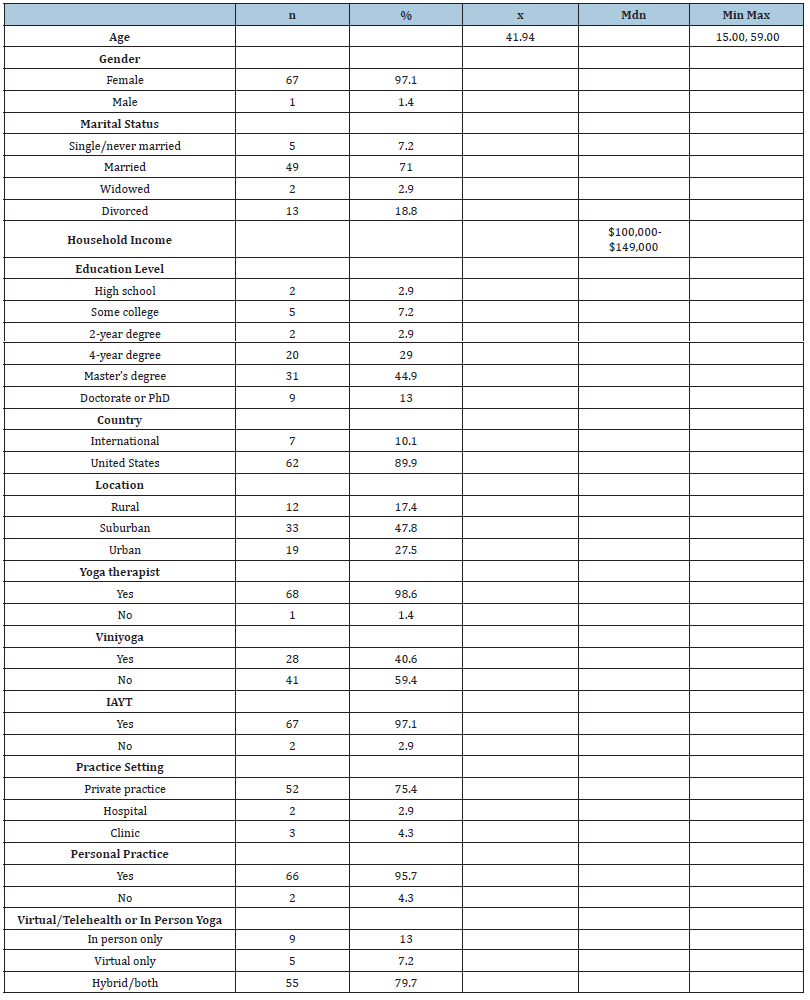

Participants’ average age was 41.94 years old (SD=9.54). Most participants are yoga therapists (98.6%) and are IAYT associated (97.1%). Twenty-eight percent are yoga trained. There were 97.1% female participants and 44.9% earned a master’s degree. Most (89.9%) identified the United States as their practice location and suburban (47.8%). Most are primarily in private practice (75.4%) with most (79.7%) practicing both online and face to face in person and endorsing personal practice (95.7%). The median sample income was $100,000-$149,000. Table 1 summarizes these results.

Table 1:Sociodemographics, sample characteristics, & their univariate statistics (N=69).

Univariate analysis of pañcamaya model &yoga therapy clients practice

Next, they were asked about their yoga therapy clients 15 presenting problems and their perspectives on if the yoga therapy has generally been very effective, somewhat, or not effective. The following frequency of participants rated these problems as very effective: Back pain (85.5% of therapists), depression (71.0% of therapists), anxiety (82.6% of therapists), and stress (87.0% of therapists). Some therapists rated their yoga therapy somewhat effective for the following problems: hypertension (55.1%), headaches (55.1% of therapists), PTSD (63.8% of therapists), 10 arthritis (63.8% of therapists), 14 and menopause (66.7%) of therapists. Therapists rated as not applicable/I have never worked with the following problems: diabetes, MS (68.1% of therapists), and asthma (89.9% of therapists). Obesity was the lone problem rated not effective by 46.4% of therapists (Table 2).

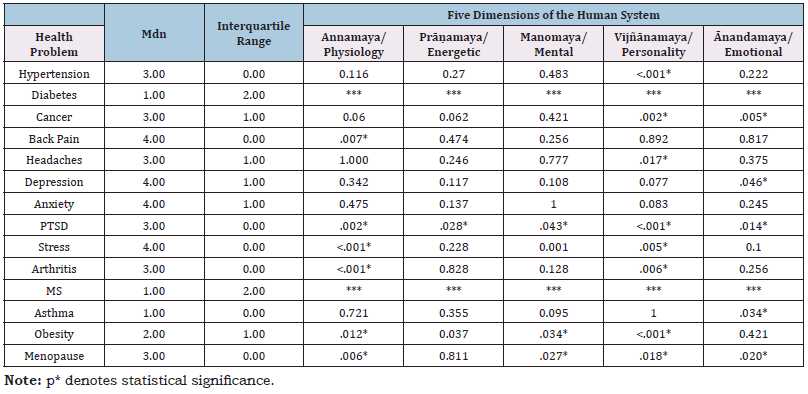

Table 2:Univariate Analysis of Health Problems and The Associations between Yoga Therapists Perceived Change in Client’s Doing Their Practice Regularly and Health Presenting Problems (N=69).

Bivariate analysis

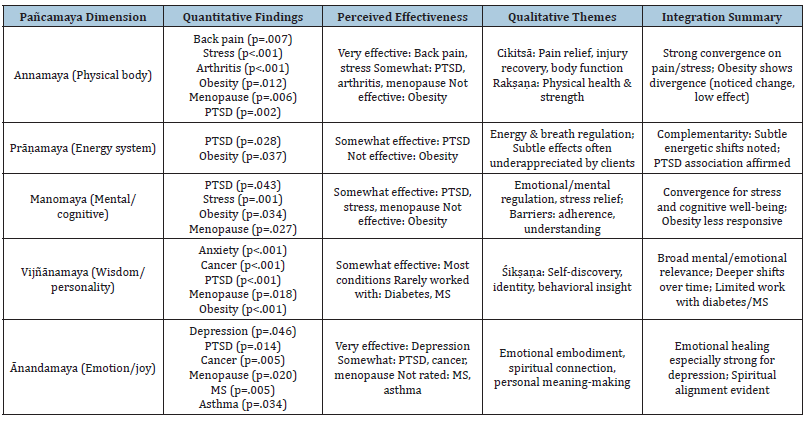

Pañcamaya model associations between yoga therapists’ perceptions about clients doing their practice regularly and health presenting problems were tested using Fisher’s Exact Test with Freeman-Haltan extension. Results (Table 2) revealed the following: annamaya/physiology and back pain (p=.007), PTSD (p=.002), stress (p<.001), arthritis (p<.001), obesity (p=.012), and menopause (p=.006) were statistically associated and; and pranamaya/energy and PTSD (p=.028) and obesity (p=.037) were statistically associated. More statistically significant associations were found in manomaya/mental and PTSD (p=.043), stress (p=.001), obesity (p=.034), and menopause (p=.027) as well as in vijnanamaya/personality and hypertension (p<.001), cancer (p<.001), headaches (p=.021), anxiety (p<.001), stress (p=.005), PTSD (p<.001), arthritis (p=.006), MS (p=.015), obesity (p<.001), and menopause (p=.018). Last, anandamaya/feelings and cancer (p=.005), depression (p=.046), PTSD (p=.014), asthma (p=.034), and menopause (p=.020).

The annamaya/physiology dimension results showed that the therapist usually or often noticed changes concerning applying the model to back pain and stress, they perceived as very effective. They usually or often noticed changes concerning PTSD and perceived the model as somewhat effective in addressing this condition as well as arthritis, obesity, and in addressing menopause. Concerning the pranamaya/energy dimension, therapists perceived noticeable changes in PTSD that were somewhat effective when applying the pañcamaya model. Whereas noticeable changes in obesity (p=.037) were perceived as not very effective.

Manomaya/mental dimension noticeable changes when applying this model were detected usually often in clients with PTSD, stress, and menopause, all of which the model was perceived to be somewhat effective in addressing these. However, the obesity condition results showed that the therapist perceived the model as not very effective.

Vijnanamaya/personality results showed noticeable occasional changes perceived by therapists concerning the model addressing hypertension, cancer, PTSD, stress, and menopause, and the model was perceived as somewhat effective in addressing these conditions. They have rarely noticed a change in diabetes or worked with this condition, but occasionally noticed a change in arthritis, MS, and obesity, but did not rate the model’s effectiveness. Last, as part of the anandamaya/feelings dimension, therapists usually or often notice changes in clients diagnosed with cancer, PTSD, and menopause that they perceive as somewhat effective whereas with depression these usual or often noticeable changes are perceived by therapists as very effective. Therapists usually or often perceive a noticeable change when applying this model to address MS and asthma and did not rate perceived effectiveness.

Qualitative strand

The mixed methods study used a convergent design that included qualitative questions integrated into a Qualtrics survey along with the quantitative strand. Participants were asked to identify challenges they’ve encountered in providing effective yoga therapy. Yoga therapists were also invited to share goals they’ve worked on in their clients’ practice according to the Tri Krama framework of yoga therapy- Cikitsā (healing), Rakṣaṇa (thriving), and Śikṣaṇa (discovering).

Themes

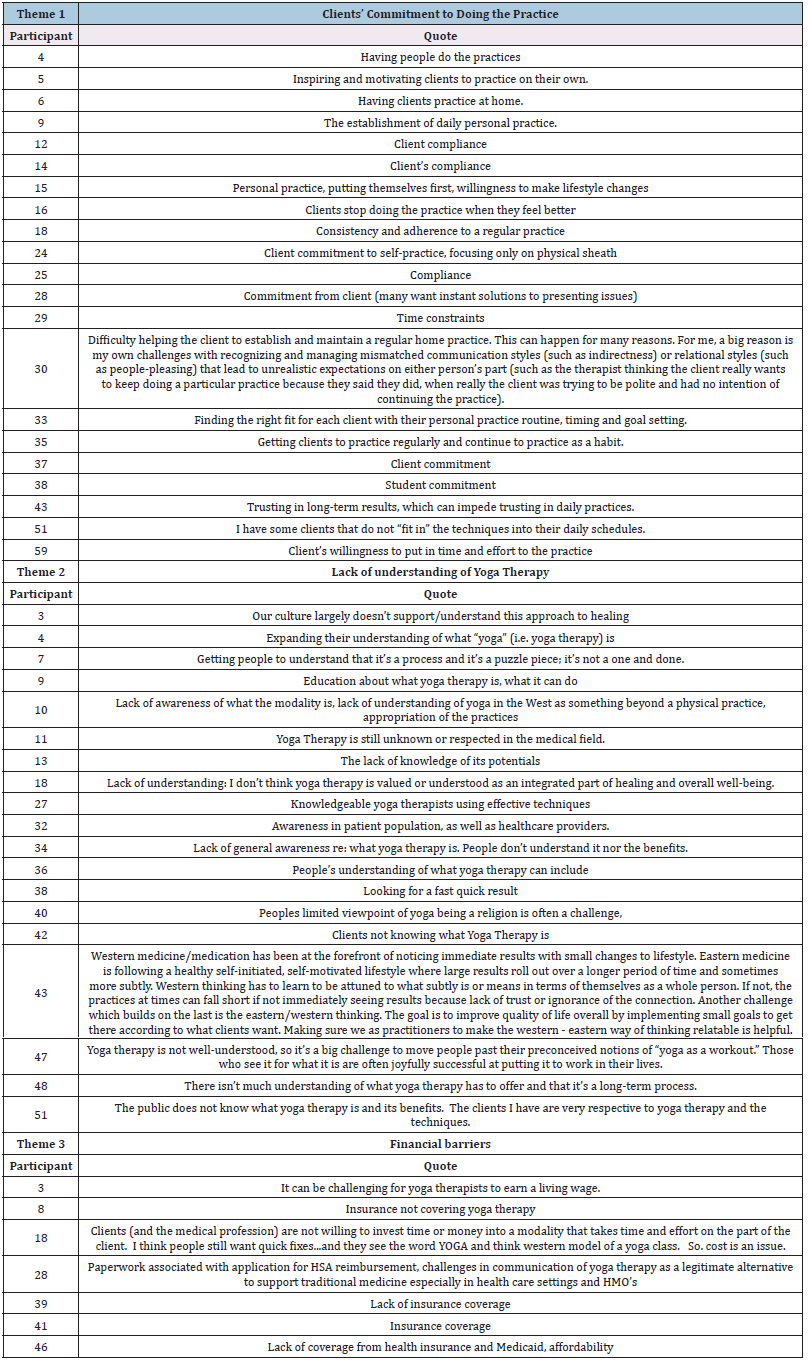

Challenges to providing yoga therapy

Participants were asked to identify the biggest challenges to providing yoga therapy from their perspective as a yoga therapist (Appendix A). Three main themes were identified as the biggest challenges to providing yoga therapy from the perspective of yoga therapist participants: 1. Client’s commitment to doing their practice 2. Lack of understanding and 3. Financial barriers. Therapists identified barriers to clients doing their practice at home as the primary theme representing the challenge to providing yoga therapy. Yoga therapists consistently described client compliance as the biggest challenge they face in their work. This barrier was explained by yoga therapist participants as having elements of challenge regarding to, “Inspiring and motivating client to practice on their own” (participant 5), “Establishing a daily personal practice” (participant 9), and “Consistency and adherence to a regular practice” (participant 18).

Appendix A:Themes describing the biggest challenges to providing yoga therapy.

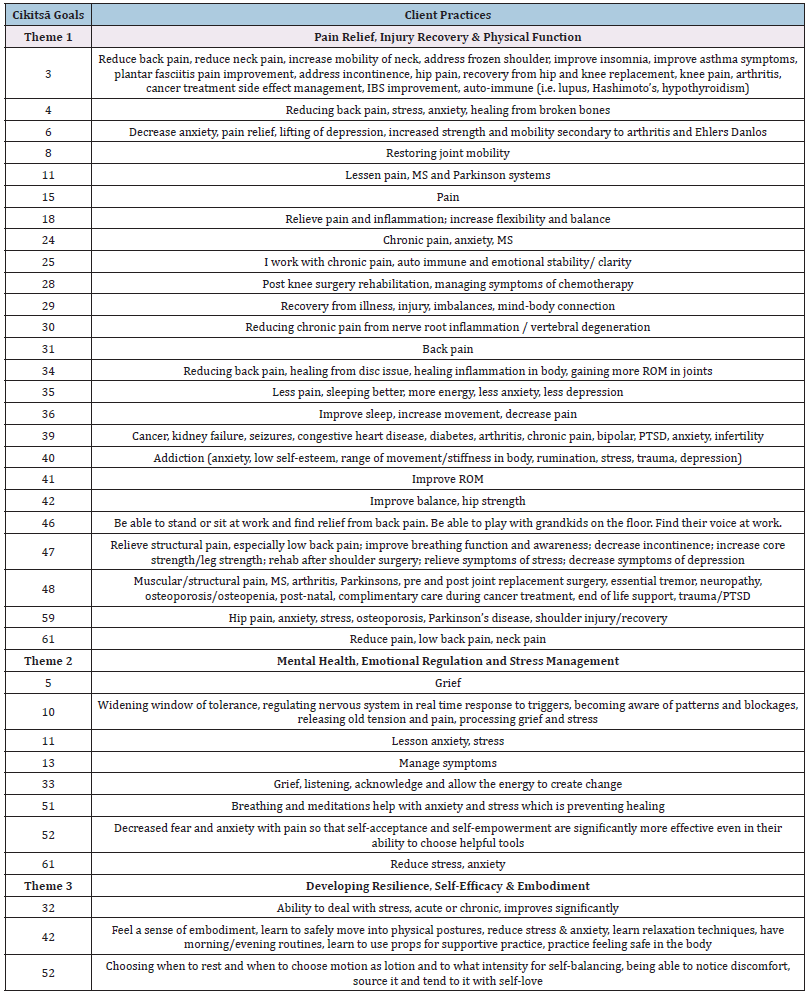

Cikitsā krama goals

Three themes emerged when yoga therapists spoke about Cikitsā krama (healing) client practices (Appendix B): 1) Pain relief, injury recovery and physical function, 2) Mental health, emotional regulation and stress management, and 3) Developing resilience, self-efficacy and embodiment. Yoga therapists working with clients on pain relief, injury recovery, and physical function are focused on reducing chronic pain, healing from injuries or surgeries, improving mobility, strength, and managing physical conditions. Participants described working on, “Reducing back pain, stress, anxiety, healing from broken bones” (participant 4), “Restoring joint mobility” (participant 8), “Relieve pain and inflammation; increase flexibility and balance” (participant 18), and “Chronic pain, anxiety, MS” (participant 24). When supporting clients working on goals related to the theme of mental health, emotional regulation and stress management, clients are seeking to manage stress, anxiety, depression, grief, and other emotional or nervous system-related concerns.

Appendix B:Themes describing Cikitsā goals in yoga therapy client practices.

Yoga therapists’ clients who are addressing mental health, emotional regulation and stress management are looking to address topics including, “Grief” (participant 5), “Widening window of tolerance, regulating nervous system in real time response to triggers, becoming aware of patterns and blockages, releasing old tension and pain, processing grief and stress” (participant 10), and “Lesson anxiety, stress” (participant 11).

Clients focused on the theme of developing resilience, selfefficacy, and embodiment have goals centered around awareness, self-regulation, empowerment, embodiment, and functional independence. Examples presented by participants include, “Ability to deal with stress, acute or chronic, improves significantly” (participant 32), “Feel a sense of embodiment, learn to safely move into physical postures, reduce stress & anxiety, learn relaxation techniques, have morning/evening routines, learn to use props for supportive practice, practice feeling safe in the body” (participant 42), and “Choosing when to rest and when to choose motion as lotion and to what intensity for self-balancing, being able to notice discomfort, source it and tend to it with self-love” (participant 52).

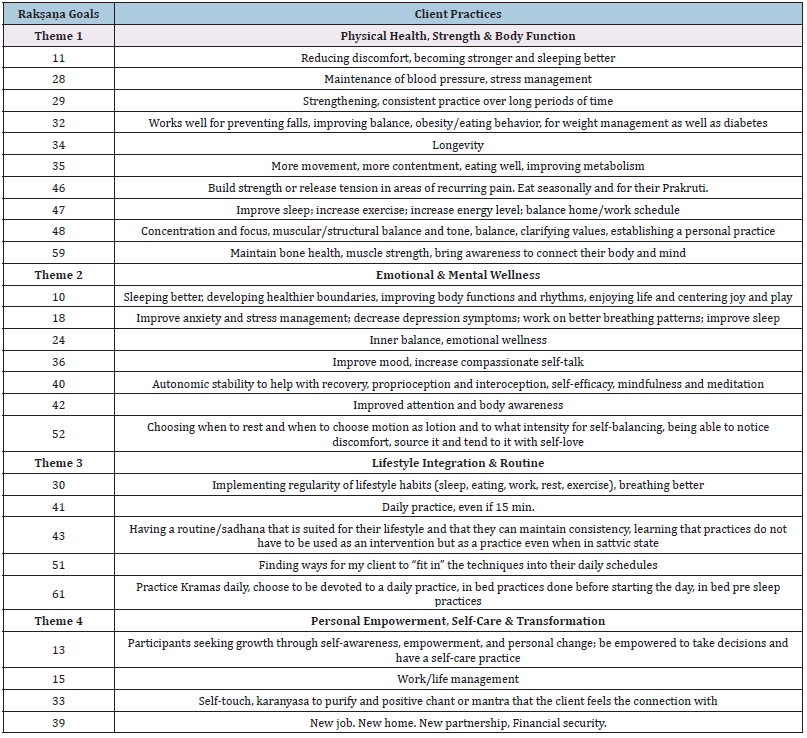

Rakṣaṇa krama goals

Yoga therapists working with clients on Rakṣaṇa krama (thriving) goals identified three themes (Appendix C). The themes that represent client Rakṣaṇa krama practice include: 1) Physical health, strength and body function, 2) Emotional and mental wellness, and 3) Lifestyle integration and routine. Participants working with clients on the theme of physical health, strength, and body function are focused on goals developed to improve physical health, manage chronic conditions, and build or maintain physical strength. Examples shared by participants of client Rakṣaṇa practice goals include, “Reducing discomfort, becoming stronger and sleeping better” (participant 11), “Improve sleep; increase exercise; increase energy level; balance home/work schedule” (participant 47), “Concentration and focus, muscular/structural balance and tone, balance, clarifying values, establishing a personal practice” (participant 48), and “Maintain bone health, muscle strength, bring awareness to connect their body and mind” (participant 59). Yoga therapists identified emotional and mental wellness as a common theme in Rakṣaṇa krama practices. Participants working on emotional and mental wellness goals are aiming to manage anxiety, stress, mood, sleep, boundaries, and cultivate emotional balance.

Participants shared examples from their clients goals including, “Sleeping better, developing healthier boundaries, improving body functions and rhythms, enjoying life and centering joy and play” (participant 10), “Improve anxiety and stress management; decrease depression symptoms; work on better breathing patterns; improve sleep” (participant 18), “Inner balance, emotional wellness” (participant 24), and “Improve mood, increase compassionate self-talk” (participant 36). Lifestyle integration and routine was named as another theme in Rakṣaṇa krama client practices. Clients working on these types of practice goals would be interested in establishing or maintaining regular practices that fit their lives and support well-being. Examples of Rakṣaṇa krama goals for lifestyle integration and routine presented by yoga therapistparticipants include, “Implementing regularity of lifestyle habits (sleep, eating, work, rest, exercise), breathing better” (participant 30), “Daily practice, even if 15 min.” (participant 41), and “Having a routine/sadhana that is suited for their lifestyle and that they can maintain consistency, learning that practices do not have to be used as an intervention but as a practice even when in sattvic state” (participant 43).

Appendix C:Themes describing Rakṣaṇa goals in yoga therapy client practices.

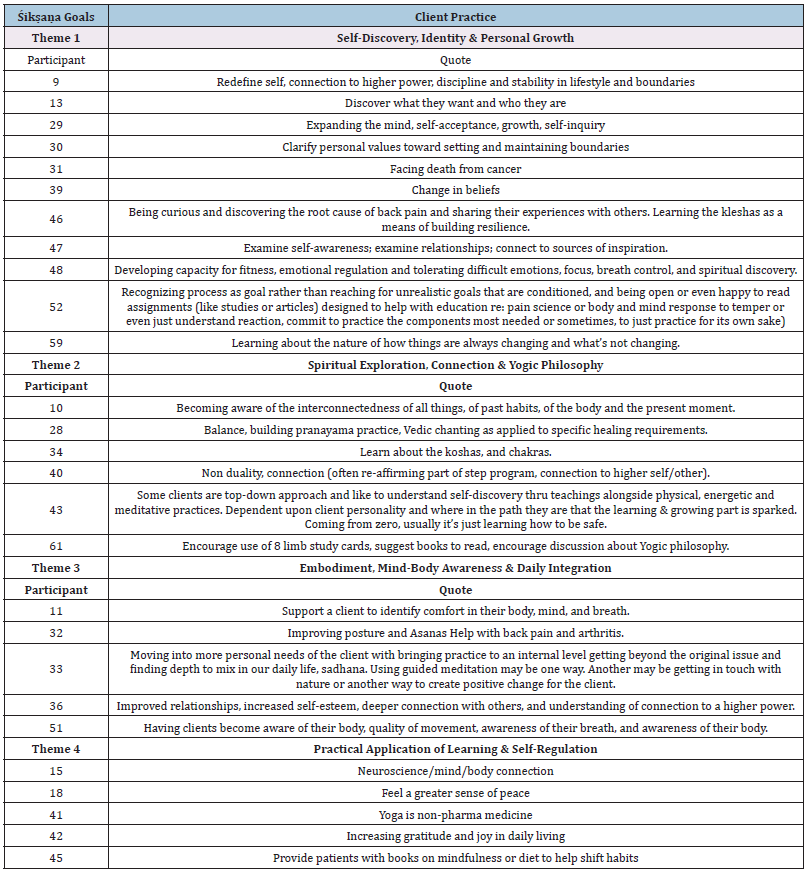

Śikṣaṇa goals

Yoga therapists identified four themes that describe Śikṣaṇa krama practice goals among their clients (Appendix D): 1) Selfdiscovery, identity and personal growth, 2) Spiritual exploration, connection, and yoga philosophy, 3) Embodiment, mind-body awareness, and daily integration, and 4) Practical application of learning and self-regulation. Self-discovery, identity, and personal growth was found to be the most common Śikṣaṇa krama theme among clients named by yoga therapist participants. Clients working on Śikṣaṇa krama goals are focused on understanding themselves more deeply, redefining their identity, exploring their values and beliefs, and cultivating resilience through self-awareness. Examples participants provided of self-discovery, identity and personal growth include, “Discover what they want and who they are” (participant 13), “Expand the mind, self-acceptance, growth, and self-inquiry” (participant 29), and “Examine self-awareness, examine relationships, connect to sources of inspiration” (participant 47). Another common Śikṣaṇa krama practice theme identified by yoga therapist participants is spiritual exploration, connection, and yoga philosophy.

Appendix D:Themes describing Śikṣaṇa goals in yoga therapy client practices.

Clients who have goals in this area are working on deepening their connection to spiritual practice, philosophical teachings, and higher meaning through yoga and self-inquiry. Yoga therapists described these goals of their clients as, “Becoming aware of the interconnectedness of all things, of past habits, of the body and the present moment” (participant 10), “Balance, building pranayama practice, Vedic chanting as applied to specific healing requirements (participant 28), and “...Understand self-discovery thru teachings alongside physical, energetic and meditative practices” (participant 43). Embodiment, mind-body awareness, and daily integration is another Śikṣaṇa krama practice theme participants identified. These clients are working toward greater embodiment, body awareness, and using their yoga practice as a daily, integrated support tool for mental and physical wellness (Appendix E).

Appendix E:Joint Display: Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings on Yoga Therapy Client Outcomes Using the Pañcamaya Model.

Examples from participant client cases include, “Support a client to identify comfort in their body, mind, and breath” (participant 11), and “Moving into more personal needs of the client with bringing practice to an internal level, getting beyond the original issue and finding depth to mix in our daily life...to create positive change for the client” (participant 33). The final Śikṣaṇa krama theme participants identified for their clients was practical application of learning and self-regulation. Clients working on these goals are building awareness and using tools, movement, mindfulness, breath, education, to improve emotional regulation, behavioral patterns, and support habit change. Client examples provided by yoga therapist participants include, “Neurosciencemind- body connection” (participant 15), “Feel a greater sense of peace” (participant 18), and “Increasing gratitude and joy in daily living” (participant 42).

Discussion

This mixed methods study explored yoga therapists’ perceptions of the impact of yoga therapy on their clients across a range of physical and psychosocial conditions, guided by the pañcamaya model of the human system. Further, it examined yoga therapy practices using the Tri Krama model and explored barriers to providing effective yoga therapy. Quantitative and qualitative data converge to suggest that yoga therapy, when regularly practiced by clients, is associated with therapist-perceived changes across multiple dimensions of being, particularly in the physical (annamaya), mental (manomaya), and emotional (ānandamaya) layers. Notably, significant associations were found between changes in these pañcamaya layers and a range of common presenting problems, suggesting a complex and multi-layered impact of yoga therapy as perceived by experienced practitioners.

Integration of quantitative and qualitative findings

Quantitative findings indicate that therapists most frequently noticed change in the annamaya, manomaya, and ānandamaya dimensions, aligning with the most reported therapeutic goals in the qualitative data: pain relief, mental health, emotional regulation, and stress management. These goals map well onto the pañcamaya framework and were often framed within Cikitsā (therapeutic) and Rakṣaṇa (maintenance and prevention) objectives in yoga therapy sessions. Significant associations between the annamaya dimension and conditions such as back pain, arthritis, stress, and menopause suggest that physical practices remain central to yoga therapy’s perceived effectiveness. This is consistent with qualitative themes in which therapists highlight improvements in physical function and pain relief as common client outcomes. The annamaya dimension also showed associations with obesity and PTSD, though the perceived effectiveness for these conditions was more mixed, particularly for obesity, which was rated as “not effective” by a significant proportion of therapists (46.4%).

The manomaya (mental) and vijñānamaya (personality) layers showed broader associations across conditions such as PTSD, stress, obesity, and menopause, reflecting therapists’ recognition of the cognitive and behavioral aspects of chronic conditions. The qualitative data supported this, with therapists describing clients’ increasing resilience, self-regulation, and self-efficacy, psychological capacities embedded in these subtler dimensions. Interestingly, the vijñānamaya layer had the highest number of statistically significant associations, including for less commonly addressed conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and MS, despite therapists reporting limited direct experience with some of these. In the prāṇamaya (energy) and ānandamaya (emotional/affective) dimensions, therapists reported less frequent changes overall but still identified statistically significant associations with conditions such as PTSD, obesity, and depression. Qualitative findings help clarify this: while prāṇamaya is recognized as subtle and more difficult to access or measure, it is often implicitly targeted through breathwork and energetic practices. Therapists described embodiment, spiritual exploration, and personal growth-all themes tied to these subtler dimensions—as emerging in both client and personal practices, particularly under Śikṣaṇa (learning and growth) goals.

Therapist perspectives on efficacy and barriers

Therapists rated yoga therapy as very effective for conditions like stress, anxiety, back pain, and depression, while somewhat effective for others such as PTSD, arthritis, menopause, and hypertension. These ratings suggest both confidence in yoga therapy’s utility and a realistic appraisal of its limitations. The nuanced view is further supported by qualitative data where therapists highlight client adherence, financial barriers, and limited understanding of yoga therapy as key challenges. These barriers may affect both the consistency of client engagement and the long-term efficacy of the practice, particularly in managing chronic or complex conditions.

Implications for practice

This study reinforces the utility of the pañcamaya model as both a theoretical and practical framework for guiding yoga therapy. Its layered approach aligns with the multifactorial nature of many health conditions, particularly those involving both physical and psychological components. Furthermore, the alignment between clients’ practice goals in the Tri Krama model (Cikitsā, Rakṣaṇa, Śikṣaṇa) and observed client outcomes underscores the adaptability of yoga therapy across the spectrum of care, from acute symptom management to long-term personal growth and self-regulation. However, the findings also highlight the need for more transparent communication about what yoga therapy entails, and strategies to improve client engagement, particularly in populations where yoga therapy is underutilized or misunderstood. Additionally, the lower perceived effectiveness in conditions like obesity suggests a potential gap in either training or intervention design that may benefit from further research and targeted strategies.

Limitations and recommendations for future study

This study has identified participant limitations based upon the use of convenience sampling. Results were based upon yoga therapists’ report of their observations of the effectiveness of yoga therapy on their clients’ presenting problems using a Likert scale. Further study regarding yoga therapy practices using the Tri Krama model could be enhanced by gathering focus group or individual interview data. Future studies should consider clients self-reporting their experience of the effectiveness of yoga therapy interventions on heath conditions. Studies designed to evaluate similarities and differences among clients’ self-report, their yoga therapists’ observation, and their healthcare providers’ perspective on the impact of yoga therapy on client health conditions is recommended. The impact of yoga therapy interventions on individuals with various health conditions may warrant examination of associated changes in biomarkers, particularly the anti-aging gene Sirtuin 1, which plays a critical role in regulating multiple physiological and pathological processes, including mental and chronic diseases. Activation of Sirtuin 1 through regular yoga therapy may have therapeutic relevance, suggesting that plasma Sirtuin 1 levels should be measured in clients undergoing yoga-based interventions [14-16].

Conclusion

This mixed methods study provides valuable insights into yoga therapists’ perceptions of client outcomes through the lens of the pañcamaya model. Therapists reported that clients experience noticeable and meaningful changes, particularly in physical, mental, and emotional dimensions, across a range of conditions when they engage in regular yoga practice. The model also revealed nuanced associations between subtle dimensions of being, such as energy and intuition, and chronic or complex health conditions, though these were less frequently recognized or clearly articulated by therapists. Qualitative findings illuminated the goals, challenges, and depth of yoga therapy practice, through the Tri Krama model, confirming its capacity to support not just symptom reduction but also resilience, embodiment, and personal growth. These results support the continued integration of yoga therapy in holistic care, particularly for conditions involving stress, pain, and emotional dysregulation. Future research should focus on client-reported outcomes, longitudinal effectiveness, and exploring how training and public education can improve accessibility and efficacy of yoga therapy interventions across diverse populations.

References

- Bossart C (2007) Yoga bodies, yoga minds: How Indian anatomies form the foundation of yoga for healing. International Journal of Yoga Therapy 17(1): 27-33.

- Kepner J, Strohmeyer V, Elgelid S (2002) Wide dimensions to yoga therapy: Comparative approaches from viniyoga, phoenix rising yoga therapy, and the Feldenkrais Method®. International Journal of Yoga Therapy 12(1): 25-38.

- Heeter C, Lehto R, Allbritton M, Day T, Wiseman M (2017) Effects of a technology-assisted meditation program on healthcare providers’ interoceptive awareness, compassion fatigue, and burnout. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing 19(4): 314-322.

- Harvey P, Cikitsā. Centre for Yoga Studies.

- Fitzgerald C, Barley R, Hunt J, Klasto S, West R (2021) A mixed-method investigation into therapeutic yoga as an adjunctive treatment for people recovering from substance use disorders. Internation Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 19: 1330-1345.

- Cattie J, Allbaugh L, Visser H, Ander I, Kaslow N (2021) Tailoring trauma-sensitive yoga for high-risk populations in public-sector settings. International Journal of Yoga Therapy 31(1).

- Kishida M, Mama S, Larkey L, Elavsky S (2018) Yoga resets my inner peace barometer”: A qualitative study illuminating the pathways of how yoga impacts one’s relationship to oneself and to others. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 40: 215-221.

- Nanthakumar C (2020) Yoga for anxiety and depression-a literature review. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice 15(3): 157-169.

- Nejadghaderi SA, Mousavi SE, Fazlollahi A, Asghari KM, Garfin DR (2024) Efficacy of yoga for posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychiatry Research 340: 116098.

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Anheyer D, Pilkington K, Manincor MD, et al. (2018) Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety 35(9): 830-843.

- Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G (2013) A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain 29(5):450-460.

- Iglesias DS, Santos L, Lastra SMA, Ayán C (2022) Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials on the effects of yoga in people with Parkinson's disease. Disability and Rehabilitation 44(21): 6210-6229.

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ (2017) Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16(1): 1-13.

- Martins IJ (2016) Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances in Aging Research 5(1): 9-26.

- Martins IJ (2017) Single gene inactivation with implications to diabetes and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Journal of Clinical Epigenetics 3(3): 24.

- Martins IJ (2017) Nutrition therapy regulates caffeine metabolism with relevance to NAFLD and induction of type 3 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and Metabolic Disorders 4: 19.

© 2025 Jennifer Vasquez. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)