- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

Geophysical Methods in Archaeogeophysical Investigations

M Emin Candansayar1,2*

1Ankara University, Engineering Faculty, Geophysical Eng Dept, Geophysical Modeling Group (GMG), Türkiye

2Ankara University Technopolis, Detectsol Geosciences Geophysics Ltd, Türkiye

*Corresponding author:M Emin Candansayar, Ankara University, Engineering Faculty, Geophysical Eng Dept, Geophysical Modeling Group (GMG), Ankara University Technopolis, Detectsol Geosciences Geophysics Ltd, Türkiye

Submission: August 10, 2025; Published: January 19, 2026

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume5 Issue 5

Abstract

This review provides an overview of three widely applied geophysical methods in archaeological investigations: DC resistivity, magnetic, and Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR). Each geophysical methods are sensitive to distinct physical parameters and presents unique advantages and limitations in various site conditions. DC resistivity is effective for mapping subsurface resistivity contrasts but is affected by highly conductive soils; magnetic methods are rapid and sensitive to ferrous materials yet susceptible to cultural and environmental noise; GPR offers high-resolution imaging of buried features, though its performance diminishes in conductive, clay-rich, or water-saturated soils. Proper data acquisition, processing, and interpretation require professional expertise to avoid misinterpretation, such as confusing noise with true anomalies. This paper emphasizes the importance of selecting the appropriate geophysical method based on site conditions and archaeological objectives, supported by literature-based evaluations.

Keywords:Archaeogeophysics; DC resistivity; Magnetic; Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR); Data processing; Method comparison

Introduction

Archaeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material remains from ancient and extinct cultures [1]. One major branch of archaeological research involves the excavation of ancient remains. Prior to conducting excavations, archaeologists first review historical documents, old maps, travelers’ accounts, previous excavation reports, and local oral histories to gather contextual information about the site. Following this preliminary research, a comprehensive desk-based study is undertaken, incorporating these historical records along with systematic field observations aimed at detecting potential surface remains, such as fragments of fired ceramics or worked stone artifacts. The integration and synthesis of these datasets provide the basis for determining the precise locations and scope of subsequent excavation activities. Archaeological excavations often extend over many years, sometimes spanning decades. For example, systematic excavations at Alaca Höyüka major Hittite cult center-began in 1935 [2] and continue to this day. Since the 1940s, geophysical techniques have been widely employed globally for the investigation of archaeological remains [3]. Various geophysical methods-including electrical, electromagnetic, and magnetic techniques-are effectively utilized for mapping extensive areas.

Archaeologists refer to these field applications as Archaeological remote sensing, Archaeogeophysics, or Archaeological Prospection [3] and [4], with “Archaeogeophysics” becoming the prevailing term in recent years. Studies focusing on the dating of archaeological objects (archaeomagnetic dating) or their provenance (isotopic provenance) provide valuable insights into ancient trade and communication networks. These broader-scale investigations are distinguished from archaeogeophysical surveys and categorized as Archaeophysics [5]. Rapid identification of archaeological objects for rescue or conservation purposes is termed “Rescue Archaeology.” For instance, following the completion of the Ilısu Dam in Türkiye, numerous ancient settlements, including Hasankeyf will be submerged. In such rescue archaeology projects, archaeogeophysical surveys enable the swift determination of artifact locations, dimensions, and depths, facilitating expedited salvage excavations. The application of geophysical methods in rescue archaeology offers significant economic benefits. By enabling faster and more accurate detection of subsurface remains, geophysical surveys substantially reduce downtime and associated costs during rescue excavations.

Based on surface surveys, archaeogeophysical investigations using geophysical methods have become a standard preliminary step for newly identified archaeological sites as well as for guiding ongoing excavations. This review focuses on three principal geophysical methods widely used in archaeogeophysical investigations: Direct Current (DC) resistivity, magnetic, and Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR). Advances in instrumentation, software, and interpretation techniques-driven by developments in computer and electronic technologies-have greatly enhanced their capability to produce accurate subsurface images. Recent applications and case studies are presented to illustrate progress in data acquisition, processing, modeling, and interpretation. The distinct physical sensitivities of each method result in unique strengths and limitations, which are discussed and compared in detail.

Geophysical Methods

This section presents the three most commonly used geophysical techniques in archaeogeophysics-DC Resistivity, Magnetic, and Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR)-covering their fundamental principles, measured physical quantities, and recent advances in data processing, modeling, and interpretation.

DC Resistivity method

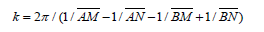

Basic theory: The DC resistivity method is a well-established geophysical technique sensitive to subsurface electrical resistivity variations. It has been applied since the early 20th century [6,7]. In this method, mainly direct current (𝐼, 𝑖𝑛 𝑚𝐴) is injected into the ground through two current electrodes (A and B) and the resulted potential differences (Δ𝑉, 𝑖𝑛 𝑚𝑉) is measured between two potential electrodes (M and N). The measured values are converted to apparent resistivity (𝜌𝑎, 𝑛 Ω𝑚) using following equation.

where is the geometric factor (in meters) defined as:

The electrodes are generally made of stainless steel [8,9]. The arrangement of current and potential electrodes defines the electrode array, and each electrode array has specific advantages and limitations. In archaeogeophysical studies, dipole-dipole and pole-dipole (left and right-sided) arrays are often preferred; joint inversion of their data can yield better results than singlearray inversions using conventional Schlumberger or Wenner configurations [10,11].

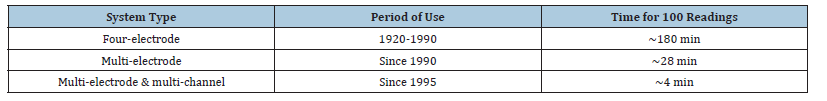

Data acquisition: Until the early 1990s, DC resistivity surveys used a four-electrode system, with manual repositioning of electrodes along the survey line. This was time-consuming, requiring ~180minutes for 100 readings. Advances in electronics and reduced component costs led to the development of multielectrode systems in the 1990s, which use more than 25 equally spaced electrodes connected via a multiplexed cable to a control unit. Computer-controlled switching enables automatic selection of electrodes for current injection and voltage measurement, reducing acquisition time for 100 readings to ~28minutes. From the mid- 1990s, multi-electrode, multi-channel systems (e.g., AGI SuperSting R8/IP, IRIS Syscal) were introduced, capable of recording voltages on 8-10 channels simultaneously. These systems can acquire 100 readings in ~4minutes, enabling rapid collection of high-density datasets suitable for 3D resistivity tomography (Table 1). Currently, archaeogeophysical surveys typically use sounding–profiling techniques along parallel survey lines to generate 3D resistivity models [11–14]. This approach allows efficient mapping of buried archaeological features.

Table 1:Evolution of DC resistivity acquisition speed.

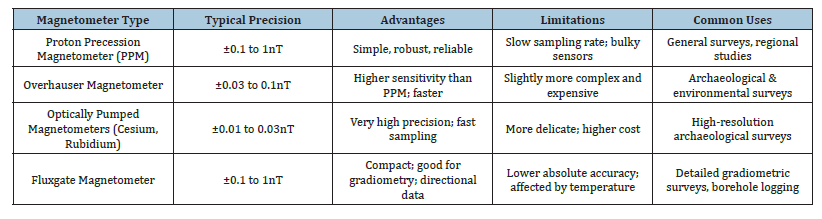

Data Processing, modeling, and interpretation: The DC resistivity method is governed by the Poisson equation, which relates current flow to subsurface resistivity distribution. Numerical forward modeling simulates expected measurements, forming the basis for inversion algorithms that estimate true resistivity values from field data. In earlier archaeogeophysical applications, 2D inversion was predominantly used to interpret DC resistivity data [10,12,15]. However, recent studies increasingly favor 3D inversion, as it offers improved spatial resolution and reduces inversion artifacts [13,16-18]. An example workflow is shown in Figure 1, where 3D DC resistivity inversion accurately delineated subsurface archaeological structures, later verified through excavation. In addition, deep learning algorithms have recently been applied to enhance inversion results, improving the detection of subtle archaeological features [19].

Figure 1:Workflow of DC resistivity in archaeogeophysical studies (adapted from [37]). The survey used a dipoledipole array with 1m electrode spacing along, totaling 280 electrodes arranged in 28 positions along x and 10 along y direction (taken web link [37]).

Magnetic Method

Basic theory

The magnetic method is one of the most widely applied geophysical techniques in archaeogeophysics, often used alongside DC resistivity surveys. It measures variations in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by contrasts in the magnetic properties of subsurface materials. The Earth’s main magnetic field is approximately dipolar, oriented from the magnetic south pole to the magnetic north pole [20]. This field induces magnetization in rocks and soils, which can be induced magnetization (aligned with the present-day field) or remanent magnetization (permanent magnetization acquired during formation or heating and cooling in the past). Archaeological materials often possess enhanced magnetic properties due to heating (e.g., in kilns, hearths, or burnt structures) or soil-forming processes such as pedogenesis, which can enrich ferromagnetic minerals like magnetite. The degree of magnetization is expressed in terms of magnetic susceptibility (κ), a dimensionless parameter.

Data acquisition

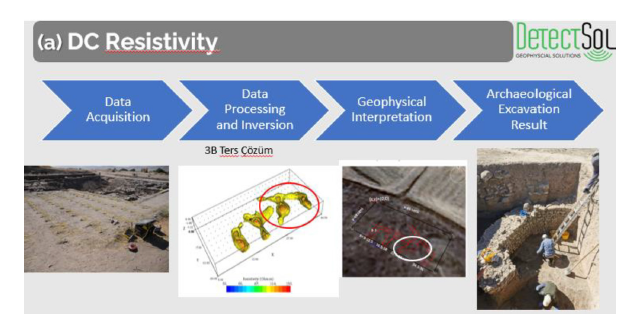

In most archaeological surveys, the measured parameter is the total magnetic field intensity, expressed in nanoteslas (nT). Anomalies in the magnetic field can indicate the presence of archaeological features such as walls, ditches, pits, hearths, or metal artifacts [20]. Magnetic data are acquired using magnetometers, which differ in precision, advantages, and limitations depending on the application (Table 2). Detailed reviews of magnetometer types and their archaeological applications are available in [21-23]. For large-area preliminary surveys, Proton Precession Magnetometers (PPM) are recommended due to their robustness, reliability, and cost-effectiveness, despite moderate precision. For high-resolution site surveys where subtle magnetic anomalies must be detected, Optically Pumped Magnetometers (Cesium or Rubidium) are preferred because of their high sensitivity and rapid data acquisition rates. When rapid mapping is required in complex or urban environments, Overhauser Magnetometers offer a good balance between sensitivity and operational simplicity. For localized anomaly detection and detailed gradiometric surveys, Fluxgate Magnetometers are ideal due to their portability, suitability for gradient measurements, and ability to provide directional data.

Table 2:Common magnetometer types and precision comparison used in archaeological surveys.

Magnetic gradiometry data

Magnetic gradiometer measures the spatial gradient (rate of change) of the magnetic field over a short distance, typically by recording the magnetic field at two different heights at each survey point and calculating the difference (in nT/m). Any magnetometer type listed in Table 2 can be configured for gradient measurements. By measuring the gradient, this technique reduces the influence of large-scale variations in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by solar activity or other environmental factors. Magnetic gradiometry enhances the detectability of subtle archaeological features that may not be visible in total-field surveys. Because it suppresses temporal variations and emphasizes local anomalies, magnetic gradiometer measurement is the preferred approach for most archaeological investigations.

Data processing, modeling and interpretation

In archeogeophysical surveys using magnetic gradiometers, data processing differs from that of total-field magnetometer data. Gradiometers measure the difference between two sensors rather than the absolute field intensity, making them inherently less affected by diurnal geomagnetic fluctuations and large-scale regional trends. As a result, corrections such as diurnal correction and Reduction to The Pole (RTP), which are essential for totalfield data, are generally unnecessary for gradiometer datasets. Nevertheless, processing is essential to enhance archaeological anomalies and minimize noise.

Common steps include:

a. Noise filtering-Removing high-frequency noise from cultural

interference or instrument limitations using low-pass filters

or smoothing.

b. Gradient filtering-Applying first- or second-derivative filters to

sharpen anomaly boundaries and improve resolution.

c. Spatial filtering-Using band-pass filters to isolate wavelength

components associated with archaeological features.

d. Interpolation and gridding-Converting irregularly spaced data

into regular grids for mapping and interpretation.

Because gradiometer data emphasize shallow, localized sources, they are particularly effective for detecting subtle archaeological features. Three-dimensional inversion of magnetic gradiometer data is rare in archaeology [24]; instead, most datasets are processed using specialized filtering and enhancement methods [25-28].

Georadar (or Ground Penetrating Radar- GPR)

Basic theory

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR), also known as Georadar, is a non-invasive geophysical method that images the subsurface by transmitting high-frequency Electromagnetic (EM) waves into the ground and recording reflections from subsurface structures [29,30]. The primary measured quantity is the two-way travel time of the reflected EM waves, which depends on the dielectric permittivity of the subsurface materials. Reflections occur at boundaries where there is a contrast in dielectric propertiessuch as between soil and masonry, or between sediment layers. GPR transmits short EM pulses, typically between 10MHz to 3.5GHz, using a transmitter antenna. These waves propagate at a velocity determined by the dielectric permittivity (ε) and magnetic permeability (μ) of the ground, given by:

where c is the speed of light in vacuum and 𝜀𝑟 is the relative permittivity. When the EM wave encounters a boundary between materials with different dielectric properties, a portion of the wave is reflected to the surface, while the rest is transmitted deeper. The reflection coefficient depends on the contrast in permittivity between the archeological target and the surrounding medium.

Data acquisition and processing

GPR surveys record the time delay between the transmitted and received signals. With an estimated wave velocity, these times are converted to depths. Multiple closely spaced profiles (radargrams) can be compiled into 2D cross-sections or 3D volumes for interpretation.

Basic interpretation generally involves:

a. Time-zero correction

b. Dewow filtering (removal of low-frequency drift)

c. Background removal (horizontal banding suppression)

d. Band-pass filtering within antenna bandwidth

e. Gain application (e.g., SEC, AGC) to compensate attenuation

These steps enhance anomaly visibility and allow recognition of patterns in radargrams [31-33].

Detailed interpretation includes:

a. Migration (to correct reflector geometry and collapse

diffractions)

b. Velocity estimation (CMP surveys or hyperbola fitting)

c. Time-depth conversion

d. 3D visualization (depth slicing and volume rendering)

These processes allow quantitative mapping of buried features and integration with other datasets [31-34]. In archaeogeophysical practice, basic interpretation is more commonly applied, but detailed interpretation is increasingly adopted in research projects to produce high-resolution 3D models.

Overview of the Geophysical Methods

In archaeological prospection, DC resistivity, magnetic, and

GPR are the three most widely used non-invasive geophysical

techniques. Each method relies on a different physical principle and

is sensitive to specific subsurface properties:

a. DC resistivity methods measure potential differences resulting

from injected current; it is influenced by subsurface electrical

resistivity variations.

b. Magnetic methods measure the total magnetic field or its

spatial gradient, detecting anomalies caused by materials

with contrasting magnetic susceptibility or remanent

magnetization.

c. GPR uses high-frequency EM waves to detect reflections at

boundaries with contrasting dielectric permittivity.

The performance of these methods depends strongly on site-specific factors such as soil type, moisture content, and the presence of cultural or natural noise sources (Table 3). Combining methods often yields more reliable interpretations than using a single technique (Figure 2).

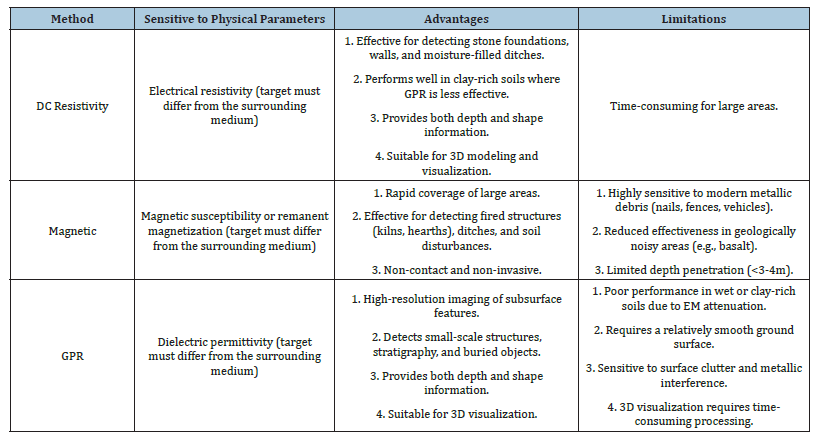

Table 3:Comparison of three main geophysical methods in Archaeogeophysics.

Figure 2:The best result by the combined use of three geophysical methods (taken from [37]).

Conclusion

This review has outlined the principles, strengths, and limitations of three geophysical methods widely applied in archaeological investigations: DC resistivity, magnetic, and Ground-Penetrating Radar (GPR). Each method responds to different subsurface properties-electrical resistivity, magnetic susceptibility, and dielectric permittivity, respectively-resulting in varying effectiveness depending on site conditions. As summarized in the comparison table, all three methods are subject to specific environmental constraints and potential sources of noise that can compromise data quality [35-37]. Careful survey design, precise data acquisition, and rigorous data processing are essential to minimize these effects and to avoid misinterpreting noise as meaningful archaeological features. For this reason, archaeogeophysical surveys should be conducted and interpreted by experienced geophysicists or geophysical engineers, ensuring that results are both reliable and capable of providing effective guidance for archaeological excavation.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted under the Ankara University Technopolis R&D project (STBP Code: 111920).

References

- Renfrew C, Bahn P (2016) Archaeology: Theories, methods, and practice, (7th edn), Thames & Hudson Publishing company, UK.

- Arık RO (1935) The results of the excavations made on behalf of the Turkish historical society at alaca Höyük in the Summer of 1936. Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1.

- Aitken MJ (1974) Physics and Archaeology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Wynn JC (1986) A review of geophysical methods used in archaeology. Geoarchaeology 1(3): 245-257.

- Gaffney C, Gater J (2003) Revealing the buried past: Geophysics for archaeologists. Tempus Publishers, Stroud, UK.

- Schlumberger C (1915) Process for determining the nature of the subsoil by the aid of electricity. US Patent 1, 163: 468.

- Binley A (2020) Tools and techniques: DC electrical methods. In: Schubert G (ed.), Treatise on Geophysics, (2nd edn), Elsevier Publishers, Amsterdam, Netherlands, pp. 233–259.

- Stummer P, Maurer H, Horstmeyer H, Green AG (2002) Optimization of DC resistivity data acquisition: Real-time experimental design and a new multielectrode system. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 40(12): 2727-2735.

- Szalai S, Szarka L (2008) On the classification of surface geoelectric arrays. Geophys Prospect 56(2): 159-175.

- Candansayar ME, Başokur AT (2001) Detecting small‐scale targets by the 2D inversion of two‐sided three‐electrode data: Application to an archaeological survey. Geophys Prospect 49(1): 13-25.

- Candansayar ME (2008) Two-dimensional individual and joint inversion of three-and four-electrode array DC resistivity data. J Geophys Eng 5(3): 290-300.

- Papadopoulos NG, Tsourlos P, Tsokas GN, Sarris A (2006) Two‐dimensional and three‐dimensional resistivity imaging in archaeological site investigation. Archaeol Prospect 13(3): 163-181.

- Papadopoulos NG, Yi MJ, Kim JH, Tsourlos P, Tsokas GN (2010) Geophysical investigation of tumuli by means of surface 3D electrical resistivity tomography. J Appl Geophys 70(3): 192-205.

- Tsourlos P, Papadopoulos N, Yi MJ, Kim JH, Tsokas GN (2014) Comparison of measuring strategies for the 3-D electrical resistivity imaging of tumuli. J Appl Geophys 101: 77-85.

- Gündoğdu NY, Candansayar ME, Genç E (2017) Rescue archaeology application: Investigation of Kuriki mound archaeological area (Batman, SE Turkey) by using direct current resistivity and magnetic methods. J Environ Eng Geophys 22(2): 177-189.

- Gündoğdu NY, Candansayar ME (2018) Three-dimensional regularized inversion of DC resistivity data with different stabilizing functionals. Geophysics 83(6): E399-E407.

- Martorana R, Capizzi P, Giambrone C, Simonello L, Mapelli M, et al. (2024) The “Annunziata” garden in Cammarata (Sicily): Results of integrated geophysical investigations and first archaeological survey. J Appl Geophys 227: 105436.

- Karaoulis M, Tsokas GN, Tsourlos P, Bogiatzis P, Vargemezis G (2025) 3D Electrical Resistivity Tomography Using a Radial Array and Detailed Topography for Tumuli Prospection. Archaeol Prospect 32(1): 197-208.

- Över D, Candansayar ME (2024) Enhancing DC resistivity data two-dimensional inversion results using a U-net-based deep learning algorithm: Examples from archaeogeophysical surveys. J Appl Geophys 227(2): 105430.

- Merrill RT, McElhinny MW, McFadden PL (1998) The magnetic field of the earth: Paleomagnetism, the core, and the deep mantle. (2nd edn), Academic Press Publishing Company, San Diego, USA.

- Tite MS, Mullins CE (1971) Enhancement of the magnetic susceptibility of soils on archaeological sites. Archaeometry 13(2): 209-219.

- Clark A (1996) Seeing Beneath the Soil: Prospecting Methods in Archaeology. (2nd edn), Routledge Publishers, UK.

- Gaffney C, Gater J (2003) Revealing the buried past: Geophysics for Archaeologists. Tempus Publishers, Stroud, UK.

- Neubauer W (2004) Geophysical prospection in archaeological sites. Archaeological Prospection 11(3): 191-202.

- Herwanger J, Pain CC, Binley A, Oliveira CRD, Harris CJ (2000) Three-dimensional imaging of underground structures using gradient data. Geophysical Journal International 142(2): 319-335.

- Fassbinder JWE (2023) Seeing beneath the farmland, steppe and desert soil: Magnetic prospecting and soil magnetism. Journal of Archaeological Science 56: 85-95.

- Becker H (2008) Magnetic prospecting of archaeological sites: New evaluation and interpretation strategies. Archaeological Prospection 15(2): 83-105.

- Cella F, Fedi M (2015) Advanced data processing and interpretation for magnetic prospection in archaeology. Near Surface Geophysics 13(6): 567-577.

- Hodgetts L, Eastaugh E, Chaput M, MacDonald R, Dawson P, et al. (2016) Archaeological mapping in the age of digital data: New approaches for field recording. Advances in Archaeological Practice 4(3): 258-272.

- Conyers LB (2013) Ground-penetrating radar for archaeology. (3rd edn), AltaMira Press, Lanham, USA.

- Daniels DJ (2004) Ground penetrating radar. (2nd edn), IET Publishers, UK.

- (2008) In: Jol HM (ed.), Ground penetrating radar: Theory and applications. (1st edn), Elsevier Publishers, Amsterdam, Netherlands.

- Goodman D, Piro S (2013) GPR remote sensing in archaeology. Springer Publishers, Berlin, Germany.

- Leckebusch J (2003) Ground-penetrating radar: A modern three-dimensional prospection method. Archaeol Prospect 10(4): 213-240.

- Zhao W, Forte E, Pipan M, Tian G (2015) Subsurface imaging for archaeology using GPR attribute analysis. J Archaeol Sci 53: 159-170.

- Manataki M, Sarris A, Papadopoulos N (2021) High-resolution 3D GPR for archaeological prospection: Methods and applications. Near Surf Geophys 19(2): 153-167.

- Detectsol Ltd.

© 2026 M Emin Candansayar*. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)