- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

The Circular Domestic Architecture of Guachimontones, Jalisco, an Interpretation Through Archaeo-Anthropological Analysis

Jorge Herrejón Villicaña1, Ismael Nuño Arana1,2*, Josafat Alberto Betancourt López1,3 † and Phil C Weigand1,4 †

1 Teuchitlan Archaeological Project (PAT), Government of the State of Jalisco, Mexico

2 Center for Multidisciplinary Health Research, University of Guadalajara, Mexico

3 Bachelor’s Degree in Nutrition, University Center for Health, University of Guadalajara, Mexico

4 Center for Archaeological Studies, El Colegio de Michoacán, Mexico

† This authors are passed away before the publication of this work

*Corresponding author:Ismael Nuño Arana, Teuchitlan Archaeological Project (PAT), Government of the State of Jalisco, Center for Multidisciplinary Health Research, University of Guadalajara, Mexico

Submission: November 17, 2025; Published: December 03, 2025

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume5 Issue4

Abstract

In the valleys at the foot of the tequila Volcano, in the state of Jalisco, Mexico, a civilization developed around circular ceremonial structures: the Teuchitlán Tradition. Its splendor reached its peak during the late formative to early classic periods (350BC-450AC). Although its architecture differed somewhat from that which would later develop in the rest of Mesoamerica, the construction methods were similar, and its ritual practices, while specific to the region, constituted a consistent homogeneity as a Mesoamerican culture. Excavations at buildings E3 and E4 of La Joyita, a residential area adjacent to the main ceremonial centers, demonstrated that they were arises on a small scale but with a high degree of ritual and ceremonial significance. Small, spiral-shaped circular buildings were found containing offerings of human remains. The remains of three children-an adolescent, an infant, and a newborn-were found as offerings among vessels and plates, most likely containing food. The excavations and anthropological analysis together showed that the offerings and rituals in these buildings were intended to invoke elemental forces of fertility, such as wind and water. Their structural and architectural composition, along with evidence of offerings of human remains, particularly children’s teeth, and food offerings-most likely amaranthindicate a ritualistic focus on fertility and abundance, which apparently prevailed during that period of the site’s development. We present a study with a comprehensive archaeological and anthropological analysis.

Keywords: Teuchitlán; Guachimontones; Housing units; Domestic ritual architecture; Rituals; Offerings; Tlaloques; Fertility; Wind and water; Abundance

Introduction

Near the center of the state of Jalisco, Mexico, lies a region known as the Valles zone, which witnessed the rise and fall of one of the most important civilizations in Western Mexico: The Teuchitlán tradition, characterized by its distinctive circular architecture. This society is known to have dominated the region’s cultural landscape, beginning its development as early as 1000BC, expanding until it reached its peak around 200-300AC, and declining around 450AC. Located within the western part of Mesoamerica, the Valles Zone occupies part of the central and highland areas of the state; it is fertile and abundant in diverse resources, which fostered the development of human societies of varying types and complexity over time. Within this region lies the present-day municipality of Teuchitlán, located at the extreme geographic coordinates 20°33’50’’ and 20°47’40’’ N; and 103°47’30’’ and 103°51’20’’ W, at an altitude of 1,300 meters above sea level. The Guachimontones archaeological site, considered the epicenter of this culture, is located approximately one kilometer from Teuchitlán, the municipal seat. This site comprises 10 circular ceremonial enclosures known as “guachimontones,” two ballcourts, funerary spaces, several residential areas, numerous terraces or leveled areas, and extensive zones that were likely used for cultivation.

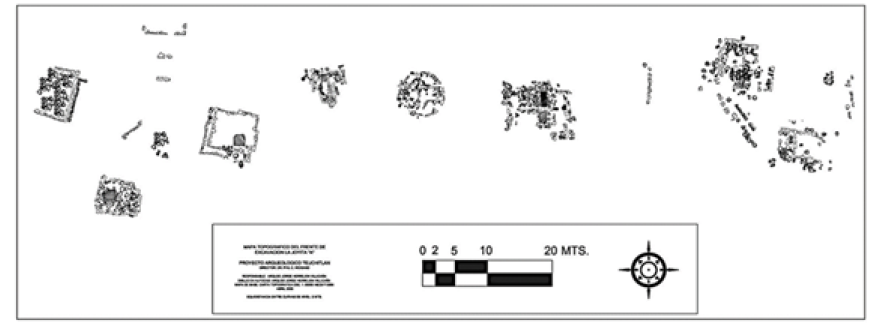

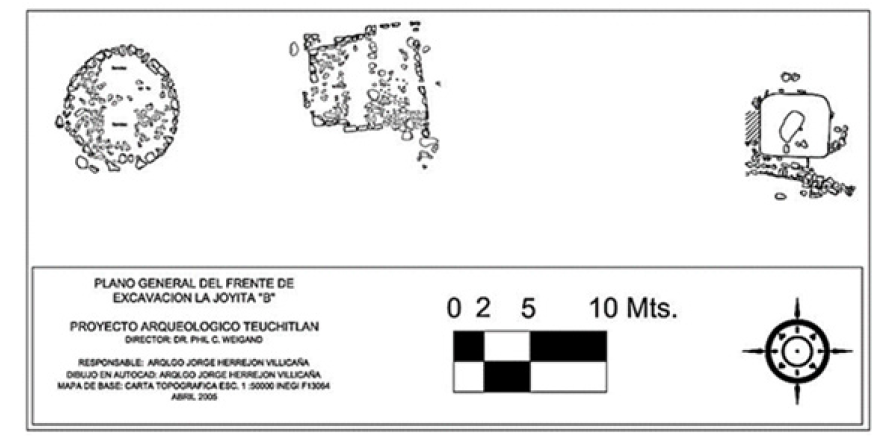

Between 1997 and 2011, excavations were carried out by a team of specialists led by Dr. Phil C. Weigand, focusing on the exploration of ceremonial circles, ballcourts, courtyards, and residential units. The study of residential areas is of paramount importance for obtaining a more complete social picture of ancient societies. Based on this premise, it was decided to explore two residential units, designated Joyita A and Joyita B, located northwest of the site’s core. Joyita A consists of nine residential units (Figure 1), including one with a circular floor plan (E4), while Joyita B contains three residential buildings (Figure 2), one of which is circular (E3). This article focuses on describing and interpreting the two circular residential units belonging to both complexes (E4 and E3 respectively) since, due to their distinctive architectural morphology, the findings made in them during the excavations, and the analyses of the archaeological and osteological materials. We estimated that their use was for ceremonial purposes, reproducing at the domestic level the rituals carried out in the community ceremonial centers. We present an analysis of all of this in this document.

Figure 1:Archaeological plan of the Joyita complex. E4 is located in the middle of the complex.

Figure 2:Archaeological plan of the Joyita B complex. E3 is located to the West.

Material and Methods

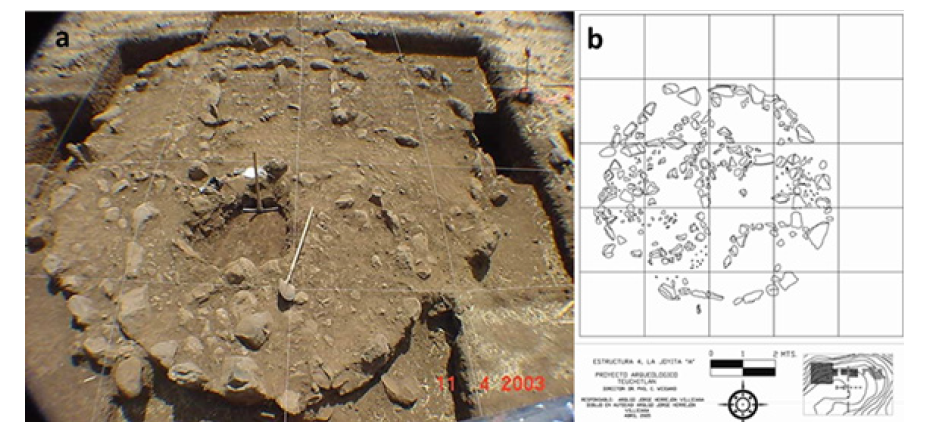

Archaeological excavations in the E4 of Joyita A

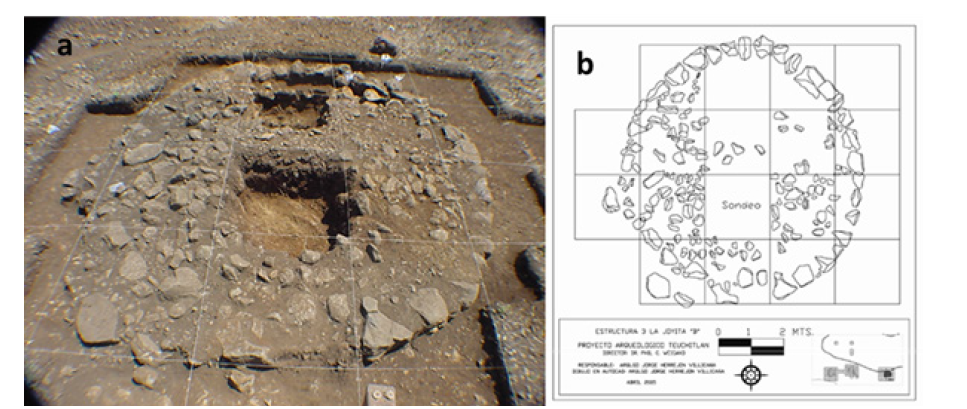

This structure has a circular floor plan approximately 6.9meters in diameter, and the entire perimeter of the building is preserved (Figure 3a). The base was built with unworked basalt rock, although the builder took particular care in selecting the smoothest sides of each stone when arranging them in the wall. Inside, the exploration revealed that the platform has two well-defined internal spaces: the first, located on the west side, has a circular floor plan; the second, built at the east end, is rectangular and has an entrance on the south side (Figure 3b). The interiors of these spaces were excavated, revealing a projectile point and a fragment (arm) of an Ameca-Etzatlán style figure. Several sediment samples were also collected and are awaiting analysis. Toward the southern end of the platform, a 2.5-meter-deep test pit was excavated. It was observed that no archaeological materials were found beneath the base of the wall. It was confirmed that the construction had at least two phases.

Figure 3a&3b:Extensive excavation of E3 and its archaeological plan. Its spiral shape is visible in the plan view.

In the first phase, the small circle now visible inside the structure was built, and in the second, the larger circle was constructed, incorporating part of the circumference of the first. The small rectangular room appears to belong to this second construction phase. This sequence gave the building a spiral shape in plan, which appears to have been intentional, as it has been observed in other circular buildings at the site. Additionally, the test pit allowed for the determination of the platform’s construction system. a layer of stone and red clay fill contained by the perimeter wall, on top of which was built the surrounding wattle and daub wall, the remains of which were found in large quantities; no remains of the floor were preserved. Among the materials recovered from inside this structure are fragments of Ameca-Etzatlán figurines that appear to have belonged to larger figures, possibly between 40 and 60 centimeters tall, considering the size of the fragments. Microfragments of a material that could be turquoise were collected, although this remains unconfirmed; these fragments were recovered from the eastern exterior of the building.

Numerous ceramic sherds and a large quantity of wattle and daub were also collected, material that allowed for some hypotheses regarding the use of perishable materials in the construction. Once the exploration of the platform’s interior was completed, the excavation was extended to the exterior of the room on the north side. On the outer face of the perimeter wall, almost exactly on the north side, a flagstone was found placed vertically, resting against the wall. While the wall’s height ranged from 35 to 60centimeters, the flagstone extended into the underlying strata beneath its base. Considering that at least three flagstones placed in this same position and adjacent to funerary remains had been found during the excavations of circle 6, it was decided to remove the stone and carefully excavate this area. After removing the flagstone, the stones forming the wall were also removed. Subsequently, at a depth of 45-50centimeters, what was designated as

Element 1 of a tomb was found: a miniature tripod basin in good condition, positioned behind the flagstone and 5 centimeters from its base.

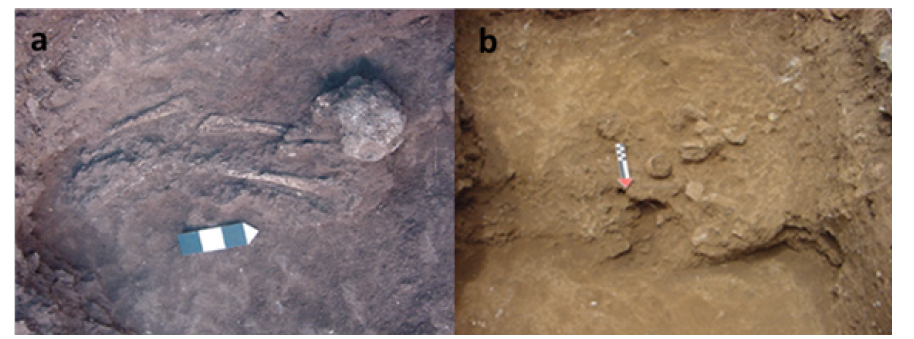

Continuing with the excavation, the following elements were discovered (Figures 4a&4b): Element 2: A tall, straight-walled bowl of the Oconahua type, red on cream, located a few centimeters south of the slab. It was found fragmented, but all the pottery shards were in place; it was face up and slightly tilted to the southeast. All the sediment it contained was recovered. Element 3: An 8centimeter diameter plate, black in color and very poorly fired; its state of preservation necessitated wrapping it in plaster bandages and removing it as a single unit. It was located approximately 20centimeters southwest of element 2, face up. Element 4: A plate of almost identical size and characteristics to the previous one; it was found in good condition, although fragmented exactly in half. It was located approximately 10 centimeters south of the previous element. Element 5: A necklace or bracelet made of tubular ceramic beads; a total of 33 beads were found (including fragments). These beads were scattered throughout the area corresponding to the tomb.

In addition to these elements, skeletal remains belonging to at least three individuals were also found: A skull lying on its side, with the face turned towards the southwest. It was found completely deformed by the pressure of the fill. It was located 15 centimeters west of element 2 (Figure 4a).

Figure 4a&4b:Burial elements E4 Bone morphology.

A. A femur-oriented north-south with its distal end towards

the south and placed under the skull. To the west was another

femur in the same position.

B. A tibia and fibula located south of the first femur and with

the same orientation; to the west was another tibia (but not the

fibula) placed south of the second femur (Figure 4a).

C. A mandible of an adult, located 10 centimeters north of

the skull.

D. A mandible of a child or adolescent (perhaps belonging to

the skull) placed 15 centimeters southeast of the skull.

E. A mandible of a young adult, found at the other end of the

tomb. It was 150 centimeters east of the skull.

F. In addition to these remains, some teeth and molars were

also found scattered throughout the burial. The only remains that

appear to have been in anatomical position were the long bonesthe

two legs of an individual, perhaps the adolescent. However, the

absence of the rest of the skeleton and the second fibula suggests

that this was a secondary burial.

Archaeological excavations in the E3 of Joyita B

The excavation of this structure confirmed that the building’s floor plan is circular, similar to that of E4. Unlike E4, the approximate diameter of E3 is 7.4meters (Figures 5a&5b). The exploration focused on determining if any vestiges of internal spaces similar to those of E3 remained, but no evidence of any was found. The entire northern sector of the building was also carefully excavated, hoping to find some funerary element that replicated the pattern found in E3, but no remains were located. However, at a depth of 1.60meters, a large flagstone was found, placed horizontally and broken into three fragments. A similar element was found in structure 4 of Group A; however, upon removing the stone and excavating 10 centimeters further, the natural tuff layer appeared without any signs of disturbance, indicating that no other element besides the flagstone was present. Towards the interior of the platform, approximately at its center, an exploration was carried out that revealed the platform’s construction system.

Figure 5a&5b:Burial elements E4 Bone morphology.

This system consisted of a layer of fill made of stone and clay mixed with archaeological materials, placed on top of the natural stratum of volcanic tuff (Figure 5a). Unusually, the tuff was located 1.2meters deep, 40 centimeters above the level of the tuff recorded in the space where the aforementioned flagstone rested. The profile of the central excavation clearly showed that the strata had been disturbed from the clay layer down, and an intrusion was detected that extended to the flagstone itself. From this, it can be deduced that a tomb or offering likely existed in the cavity. One possibility is that the offering consisted of organic elements and therefore disintegrated completely. Another possibility is that the inhabitants of the house reopened the space to remove the items. The intrusion cannot be attributed to looting since the layer of fill stone was not disturbed.

Bone material

Each piece was carefully cleaned to remove soil and attached elements that could be important from a taphonomic perspective for explaining possible morphological alterations. Subsequently, they were classified and arranged according to the provenance records from the excavation process, and the individuals involved in the offerings were identified. Ages were estimated according to the nomenclature of the International Association of Dentistry (IAO) [1]. For the anatomical positions of the teeth, we relied on the methodologies of Schour and Massler in Brothwell [2], Hillson [1], and White [3]. For the characteristics and variations of dental morphology, we used the methodologies of Gomes Valdés 2008 and the International Association of Dentistry (IAO) [1]. Aid to the Arizona state university Dental Anthropology System (DAS/ASU) [4].

Figure 6:Burial elements E4 Bone morphology.

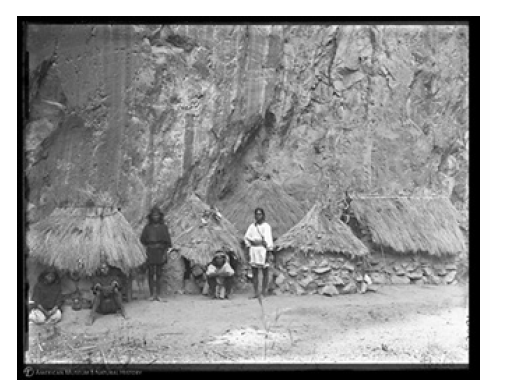

These houses, which were circular and rectangular, were then abandoned and had stones in the openings that served as doors. One night when I had to sleep in the smallest one, I saw that it was barely long enough for me to stretch out completely” [5]. Given that the aforementioned hypothesis may directly influence the interpretation given to the circular residential structures, a more detailed analysis of this hypothesis is necessary. Weigand argued for the presence of Ehécatl in Guachimontones by referencing the decoration of the pseudo-cloisonné vessels that carl lumholtz acquired on one of his trips to Mexico, in which Weigand identified a possible representation of this god: “The highly complex iconography depicted on pseudocloisonné vessels has always been recognized as sophisticated art since Lumholtz (1903) collected 43 pieces of this ceramic style in Estanzuela, Jalisco.

Although not recognized as such at the time, by the early 1970s it was obvious that the looted tombs from which Lumholtz’s collection (now housed in the American museum of natural history in New York) originated belonged to a ceremonial center within the proto-urban complex of Teuchitlán. (…) The link between pseudopartitioned pottery and the later ceremonial circles is as strong as that between the figurines from shaft tombs and the early circular buildings” [6].

In this paragraph, Weigand lays the groundwork for his

argument, stating that:

A. Lumholtz was in Estanzuela,

B. He collected 43 artifacts, and most importantly,

C. These artifacts are contemporary with the circular

architecture of Guachimontones.

Cach proposed an initial pantheon of gods at Guachimontones based on figurines found during the exploration of tombs in Circle 6. Regarding these figurines, he states that they are “figurines that represent deities and the supernatural entities that accompany them. These types of figures are specific representations within a hierarchy that comprises a pantheon related to an institutionalized religion. Therefore, we can find these divinities repeated with the same attributes, making them unmistakable” [7]. Continuing this line of argument, how lists these attributes: short arms, obesity, enormous noses, deformed (tubular) heads, and exaggerated facial features (mouths and eyes). However, from an artistic point of view, these characteristics appear in practically all the figurines (complete and fragmented) recovered at Guachimontones. These features do not make the figures unmistakable deities, nor are they supernatural attributes; They belong to the realm of style, since realism (aesthetically and strictly speaking) did not develop in the plastic expression of these figures. Of the nine figures he analyzes, he only identifies “with certainty” one rain deity (without explaining which attribute defines it), and describes two of them as “unidentified deities”; the argument, therefore, is not convincing.

After establishing the contemporaneity of the vessels with the circular architecture, he continues: “It is possible that much of the pseudocloisonné iconography is related to solar and celestial symbols. The representative figures on pseudocloisonné vessels are not serpentine but very often bird-like (although serpentine motifs occur in direct association with bird-men). Those collected by Lumholtz are in good condition, but they are certainly not the only examples of such representations. For many years, I have suspected that the most bird-like individuals depicted on pseudocloisonné vessels were interpretations of the western prototype of Ehécatl” [8]. Based on this suspicion, he conducted a detailed analysis of the iconographic elements, concluding that some of these pieces depicted a deity that was an ancestor or “prototypical” of Ehécatl, while others represented sequences or series of figures belonging to dynastic lineages. The interpretation of the symbols and figures is not without merit, but it faces two fundamental problems:

A. The provenance of the vessels. In the previously cited paragraph, Weigand mentions that Lumholtz collected the pieces in the town of La Estanzuela, but a careful reading of Volume II of “unknown Mexico” reveals that he did not visit that town, and that he acquired the materials during the last stage of his journey, already in Guadalajara and after having arrived from Michoacán: “In 1898 I obtained there (referring to his stay in Guadalajara) a very interesting collection of ceramic pieces that some workers had found at the La Estanzuela hacienda, between Guadalajara and Ameca. They told me that they came across a large number of dead bodies, some of whom were seated and others standing or lying down, and that with them were many jars” [9]. The number of pieces acquired also does not match; Weigand states that there were 43 pseudo- partitioned style vessels, but Lumholtz notes: “I bought 112 pieces from them, 35 painted incaustic (referring to pseudopartitioned) and several very well preserved. When I learned of the finds, a reseller had already acquired the most valuable vessel, but I managed to recover it (image on the left. American museum of natural history). It is the one depicted on the previous page, whose decorative drawing I provide in detail on Plate XIII” [9]. Plate XIII, to which Lumholtz refers in this paragraph, is the one Weigand used as the main object of his analysis (Figure 7). Thus, the information regarding the provenance and context of the objects reached Lumholtz secondhand, and in the case of the main vessel, tertiarily, which raises reasonable doubts about the origin and context of the pieces.

Figure 7:Decoration of the pseudo-cloissoné vessel acquired by Lumholtz in Guadalajara.

B. The contemporaneity of pseudo-cloisonné vessels with circular architecture. Even after the first excavation season at Guachimontones in 1999, Weigand maintained that the Teuchitlán tradition had reached its decline as late as 900AC and even 1000AC, while placing the vessels in a period between 400 and 700AC [10], a timeframe that has indeed been confirmed by the discovery of this type of piece at Talleres 3, La Higuerita [11], and in the box tombs of Tabachines [12], for example. Within that chronological framework, it seemed safe to assert that the vessels were contemporaneous with the circular buildings, and he reiterated this idea [13]. However, after five excavation seasons at Guachimontones that yielded several c14 dates, it became clear that the decline of the archaeological site did not extend beyond 300 or 400AC at the latest.

Beyond chronology and iconography, these pots also exhibit two characteristics that identify them with the Grillo complex: specifically, the beveled or “crimped” rim [14] and the human face-shaped effigy applied to the appliqué on the same rim [15]. These attributes have not been recorded in the analysis of ceramic materials from early contexts at Guachimontones. Thus, we can know with certainty that these vessels are not contemporary with Guachimontones, and therefore the proposal of an Ehécatl “prototype” based on this iconography is untenable, an opinion shared by other researchers [16]. With the hypothesis of the presence of Ehécatl (or his prototype) at Guachimontones conclusively ruled out by these arguments, the connection between circular architecture and wind has other foundations, as we will see below. Although the exact meaning of the spiral (or cut snail shell) in the specific context of the Guachimontones site is difficult to discern, in central Mexico the snail shell was an emblem of the wind when cut transversely (ehecailacacozcatl). In the Aztec worldview, the universe was a layer of water that existed beneath the earth, and the water was inhabited by fantastic animals such as the cipactli, or lizard. As an aspect of these aquatic realms, the snail shell was an important element in Aztec iconography as a symbol of fertility, life, and creation. Sometimes, the serpent is depicted with its body coiled, resembling the spiral of the cut snail shell, directly associated with water and fertility [17].

In the Borgia codex, Quetzalcoatl/Ehecatl is depicted wearing spiral-shaped ear ornaments made of shell, a pectoral made of marine snails called the “spiral jewel of the wind,” and a mantle of shells draped over his back. This deity was associated with spiral forms, twists, and roundness; circular temples were erected in his honor (one exists in Calixtlahuaca and Cuicuilco) because it was believed that this structure offered less resistance to air movement, and round fruits were offered to him [18]. In Mesoamerica in general, and in the West in particular, snails and shells were associated with the god Tlaloc, the bringer of water and rain: “The snail had fertility properties due to its connection with water and its deities in the Mesoamerican imaginary since the Preclassic period” [19]. Thus, the spiral shape, or cut snail, is also associated with the deity of wind, not only water. It is possible that the association of the spiral symbol with wind and water arose from the observation of eddies created by the wind, including large atmospheric whirlpools such as tornadoes [20], although the whirlpool has also been linked to water. It is noteworthy that the symbol is present in many other cultures outside the Mesoamerican time and place, with the same meaning.

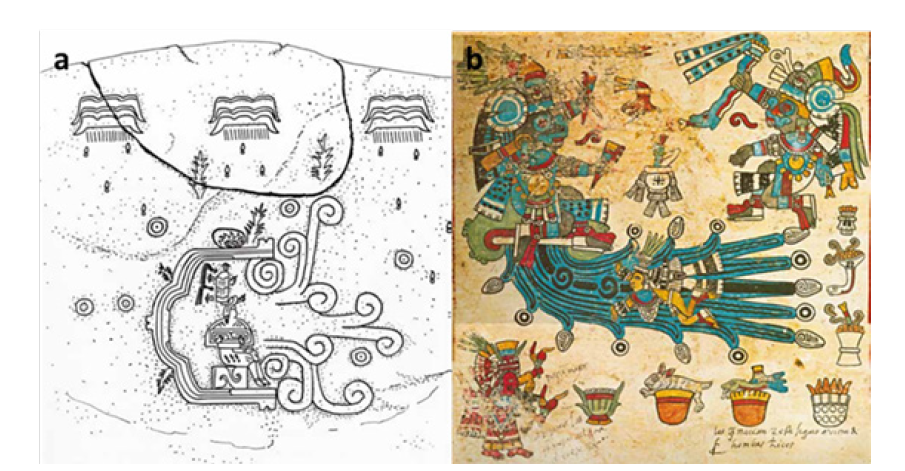

The fundamental importance of wind lies in its role in carrying rain, essential for the life of sedentary agricultural societies. In Mesoamerica, this air/water relationship appears represented as a spiral as early as 900-500BC (Figure 8a) in Olmec reliefs [21] and is observable in ceramic vessels, reliefs, mural paintings, codices, and various graphic representations throughout the pre- Hispanic period (Figure 8b). Through this air/water association, the spiral obtained from cut marine snails integrated this marine species into the symbolic repertoire associated with air/water. Similarly, the coiled serpent also alludes to the spiral of the snail, representing water (Figure 9). These symbols have appeared in various contexts at sites contemporary with and culturally linked to Guachimontones; In the shaft tomb excavated at Huitzilapa, one of the principal figures had three marine snails placed on his genitals, thus associating the snail with fertility. Both the serpent and the spiral fretwork have appeared in the decoration of red-onwhite Oconahua vessels, and there is a sculpture in the shape of a rattlesnake located near Plaza B at La Joyita A.

Figure 8a&8b:Relief of El Rey de Chalcatzingo. Tláloc, god of rain with his lightning-serpent scepter and the precious water that springs from the jaws of the hill.

Figure 9:Chalchiuhtlicue, goddess associated with the day Serpent. Note the spirals in the river that flows from her. Detail from the Borgia Codex, plate 65.

Furthermore, ethnographic studies have documented the Huichol custom of applying face paint when searching for the jículi (a type of edible flower) or when performing propitiatory ceremonies. Figure 10 shows the design of the face paint applied by the women. “The illustration (…) depicts four jículis. Above the nose are clouds. In the middle of the forehead are two coiled snakes, symbols of rain, and three rows of clouds, from which rain falls, painted in vertical lines on either side of the face. The effect of water is perceived in the kernels of corn designated by the dots below, as well as by a gourd vine with leaves and fruit, painted on the beard” [9]. The large spirals painted on both sides of the face symbolize the jículis, and in this case, the spiral formed by the snake, as well as the snake itself, represent water.

Figure 10:Huichol face painting.

There are other indications of the air/water link in the circular architecture of this region. For example, at the Hacienda de Guadalupe hoard, Adela Breton recorded the presence of another symbol associated with water: “One of the three bracelets I have is a simple shell band. Of the other two shown, one has 26 frogs carved in low relief (a small part is broken), and the other has four two-headed snakes alternating with four frogs. Small shell frogs and beads of various shapes may have formed necklaces, and there are some curious small shell figures in the shape of silhouettes too. All of these are in the Bristol Museum, and are a sample taken from the large number found at the hacienda. The frogs seem to have represented some Mexican deity, since in Guanajuato there are some rocks above the city that have the appearance of frogs, and these were considered tutelary gods by the indigenous people” [22]. The frog is an animal directly associated with water, and its appearance in burials located inside central circular altars is significant. The presence of these symbols (spiral, snail, snake, frog) seems to support the hypothesis that at least some of these central altars are dedicated to wind and water deities and that these ritual spaces were reproduced at the domestic level in residential units.

According to the argument presented above, and having discarded the hypothesis of the “prototype” Ehécatl, we consider that the symbolic elements of the spiral, the snail, and the snake, which are materialized in both ceremonial and domestic architecture, support the idea that these spaces were dedicated not to an institutionalized god, but to a supernatural force that controls winds and rains, from an animistic religious perspective. “In constructing their worldview and in the corresponding rites, these peoples (Mesoamerica) blended precise knowledge with magical beliefs about the existence and personification of meteorological phenomena and mountains; all of them were conceived as living beings” [23]. López Austin and Velásquez define the difference between gods and supernatural forces more precisely: “Supernatural beings are divided into forces and gods. Forces are entities that enable action and growth; they reside within both imperceptible beings and creatures; they can be increased and transmitted voluntarily and involuntarily, and they lack personality. In contrast, gods possess a personality so similar to that of humans that they understand human expressions and possess a will susceptible to being affected by human action” [24].

The wind-water connection with the circular structures in the residential units can be substantiated based on other data; the ceramic models representing the Volador ceremonies also constitute supporting evidence. Archaeologically, traces of the large poles that support the volador have been found in the central altar of circle 2 in Guachimontones and in the central altar of the excavated circle in Llano Grande [25]. Furthermore, recalling the cavity detected in E3 of Joyita B, this type of behavior was observed and recorded by the anthropologist Carl Lumholtz during his visit to the Huichol region at the end of the 18th century. Lumholtz described small sculptures of deities, sometimes made of wood and occasionally of volcanic stone, which were dressed and decorated, and placed on small equipales (traditional chairs) as a sign of reverence: “The gods also have their chairs, and it is assumed that they occupy them; but they are small and resemble children’s toys, their main purpose being to express an idea of reverence. In the festival I am referring to (dedicated to the subterranean gods), there were several other curiosities that contribute to attracting the gods into the presence of the people, such as small symbolic objects, hung on the backs of the equipales, or placed on the seats” [9].

These figurines are movable; they are placed at the beginning of the festivities and removed once they have concluded, being stored in niches inside the temples. From time to time, some lose their value and are replaced by new ones, as is the case with the figures representing the fire god Tatevari, which are replaced annually. Occasionally, when the figures have not lost their value, they bury the used ones in small pits dug in the center of the temples. Near a sacred cave called Jainótega, Lumholtz described the following: “What was most striking was a tiny temple, seemingly very new. I was told that when the region was threatened by a great drought, the Huichol people averted the evil by building this small temple and placing within it a new image of the goddess. The structure is a miniature replica of the ordinary temple, except that its entrance faces west instead of east. The crude little idol rests on a lava disk, much like a warrior on his shield. The disk is about a foot in diameter (approximately 30centimeters) and is at ground level. Having asked to see what lay beneath, they willingly lifted the statue, placing it on one of the three equipales behind it. They removed the disk and discovered a circular opening about two feet deep (around 60centimeters) that widened toward the back, where there was another image of the same idol on a small equipale.

It was only eight inches tall (20.32centimeters) and, like the one above, was made of solidified volcanic ash. Some ceremonial arrows with symbolic attachments, a votive gourd, and a small lava disk on which food offerings for the god were placed, such as corn kernels, bread, chocolate, tesgüino, etc., had been placed on it. The figure is older and more sacred to the Huichol than the larger one; because the volcanic material represents the god in a more direct and powerful way” [9]. Several details in this description are noteworthy. First, the small size of the temple, built to the appropriate scale to represent the house of the god, and which only has room for a few people. Lumholtz explicitly mentions that the small temple was made by reproducing, on a smaller scale, the characteristics of the full-size temple. Second, there is the anthropomorphic figure, portable and surrounded by numerous offerings, including organic materials. Below it is the hollow that houses the older figure, a hollow that, based on the description, resembles bottle-shaped tombs.

It is clear that the figure was placed in the hollow with the possibility of removing it and continuing to offer gifts, which is why it was not covered with earth. As we can see, there is a correspondence between Lumholtz’s description and the archaeological remains of E3. It is important to emphasize that this is not to claim that the ritual and/or the gods to whom it was dedicated were the same in both cases; the analogy is limited to three basic material aspects:

a. The reproduction of the community temple with all its

details, but on a reduced scale, within a local context;

b. The placement on the surface of the room of a portable or

removable ritual object to which offerings containing organic and

inorganic materials are dedicated; and

c. The presence of a niche in the center of the room

containing one or more ritual objects, also portable or removable,

placed together with their offerings and ritual equipment.

Anthropological analysis of the bone material

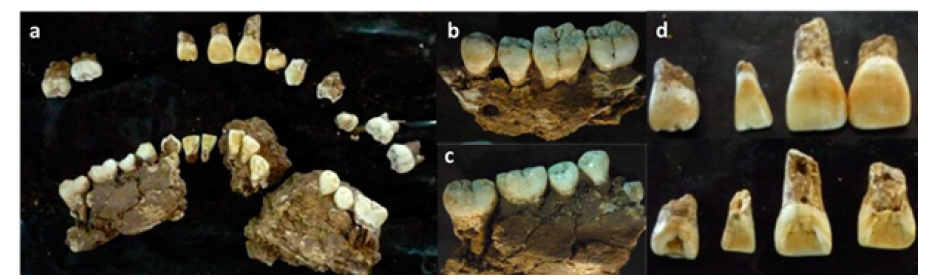

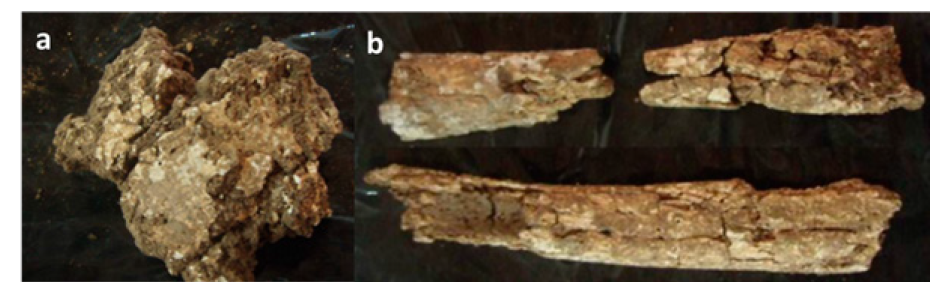

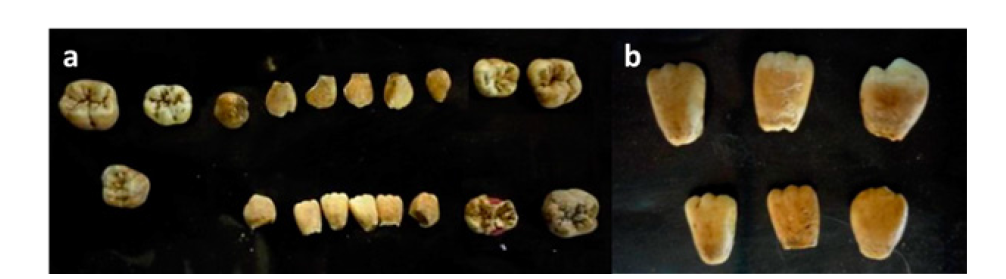

The main group consists of teeth, which based on their number and characteristics, correspond to two young individuals. The second group consists of an irregular fragment of cranial vault and two long bones; the rest are multiple fragments less than 1cm in length in very poor condition of preservation [26].

Individual 1: The first group of teeth, based on their eruptive composition, corresponds to a young person between 12 and 14 years old, due to the presence of all permanent teeth, premolars and molars (1 and 2), except for tooth 3, which erupts fully at age 15 and erupts between 21 and 30 years of age [2]. All molars have permanent roots, supporting their final eruption. The set lacks a canine, premolars, and the first upper left molar, as well as the second lower right molar. There is no presence or evidence of three molars or their roots, so the individual is probably younger than 20 years old. The upper incisors are wide and exhibit a very marked shovel-shaped variant (posterior excavation), while in the lower incisors it is slight (Figure 11) [27]. The width of the teeth suggests a possible male individual. The dentin is shiny, of adequate thickness, and complete, pearly, and in excellent condition. There is no evidence of intentional tooth modification, dentin or dental hypoplasia, malformation, or signs of nutritional deficiencies; the size is normal. The third molar is not attached to the mandibular alveolus, supporting the identification of a young person in puberty. There is slight wear on the first central incisors (M1s) and lower premolars. In addition, an irregularly shaped fragment of cranial vault, between 6 and 8 cm in diameter, was found. Its location is uncertain due to the advanced deterioration of the fragment, but its curvature suggests it may represent the parietal bone, with a thickness of 0.4 to 0.5cm. Two fragments of long bones, which based on their shape may represent femurs, were also found. The longer one is 16 cm long and, due to its curvature, appears to be the left femur. The other two are fragments of the same bone, which together measure at least 15 cm. Both are in very poor condition (Figure 12).

Figure 11a-d:Dental grouping of the first individual, b. Premolars and molars of the mandible still in their sockets in a good state of preservation, c. Note the pearly luster of the dentin, a fact that supports its good nutritional state and the little dental wear. d. Broad appearance and with posterior excavation of incisors.

Figure 12a:Fragment of cranial vault in poor condition, still attached to the block. b. Fragments of long bones in poor condition; based on their morphology, they are probably fragments of the femur.

Individual 2: The second group consists of nearly complete teeth from an individual whose dental composition and stage of growth indicate a 4-5-year-old child [2]. The teeth are in fair condition, and all are primary dentition, also known as deciduous or primary teeth. There is no evidence of hypoplasia, malformations, or any other alterations. However, they exhibit a very peculiar variant called serrated or dentate teeth, which gives the appearance of teeth with a saw-like upper edge. This variant suggests an intentional modification, as if the teeth were filed or worn down to resemble the edge of a saw (Figure 13). However, this variant is normally expected in children of this age due to their immature tooth growth.

Figure 13a&13b:Teeth of individual 2, corresponding to an infant of 4 to 5 years of age. B. Immature teeth with a serrated shape due to the characteristic growth stage in infants.

Individual 3: The third individual was found on the south side of Room 2, the central temple of the circular residential area, facing a hearth. It represented a baby, most likely a newborn, given its small size and lack of teeth. In addition to its thinness and fragile state of preservation, it crumbled to dust as soon as it was lifted, and even after being removed as a block, no fragments could be preserved, as it had all dissolved into the earth.

Osteological analysis and anthropological interpretation

Regarding the information obtained through the osteological analysis of the remains from tomb E4, it can be said that the ideological implications of these burials are significant, as the bodies underwent some form of treatment prior to their placement in the tomb. It is unclear, however, whether the bodies were dismembered or if the bones were moved from elsewhere. The presence and composition of bones and teeth in a residential area, as well as the existence of a small, circular ceremonial enclosure, demonstrate that this is very likely a ceremonial offering and not a funerary burial. The conditions of deposition, the combination of the bones found, the absence of other bones, and the location where they were discovered-which appears to have represented a small but important part of the residential complex-lead us to believe that this offering may have been made to a deity, as a request for a specific activity they were engaged in. Although the bone offering is small, the presence of human bones, particularly those of children, indicates the high importance of both the offering and the site.

Because it is located very close to what is currently the most ritually significant area of the entire pre-Hispanic settlement, Circle 6, due to the offerings found there, and because of these and other offerings of ceramics, obsidian, and other materials, we could say that the site was not exclusively residential. It is possible that multiple ritual acts took place there, such as the manufacture of ceramics for other rites or for banquets that could have been offered to a considerable number of people during these ceremonies, as well as in public events. The most important aspects to highlight in the analysis of the offerings to determine their meaning focus on three fundamental elements. The first is the type and combination of bones found. The combination of body parts indicated the action or event to be performed by the person being offered. In this case, the presence of femurs and tibias, corresponding to legs, alongside a skull indicates strong guidance and a high level of understanding of the event; that is, the offering was intentional, imbued with a profound thought (in accordance with the Tonalli). The legs, meanwhile, signify walking, leading to a place [28,29,1].

The other important group of offerings in this sense is the set of teeth, which correspond to two very young individuals. In this context of bodily significance, according to previous authors, teeth represent abundance or fertility. The grammatical meaning of the Nahuatl glyph for teeth signifies abundance (Sullivan 1998). Therefore, its meaning in this sense can be summarized as offerings directed toward a request for abundance and fertility. The god who could provide abundance and fertility was the God of rain and water, who came in storms to bring fertility and life to the crops and with them have abundance [30]. Tlaloc, along with Quetzalcoatl for the Toltecs, were truly Mesoamerican gods, as almost all cultures had their respective representations of deities in the same sense [30,31]. Guachimontones should have been no exception as a Mesoamerican culture; but to this day, we do not know the true name given to it by its original inhabitants. An interesting point to study will be the comparison of dental form variations, given the discrepancy in features with the variations found in a previous study of individuals from the West, but from the Late Classic and Early Postclassic periods, around 1000 years later [32].

This finding could indicate that there is no biological relationship between populations that inhabited the same area, albeit at different times, which would suggest processes of growth/ splendor and decline by one ethnic group or population, and at least one process of reoccupation and decline by a different ethnic group. However, these findings can be verified by conducting a comparative study of dental variants and, above all, a genetic study of parentage using ancient DNA, which we plan to carry out in the near future as another phase of the investigation. The second aspect observed was the age of the individuals offered. The presence of a newborn’s skull, the teeth of two other childrenone 4-5 years old, the other with the skull and lower limbs of a 12-year-old-were found. These children were offered in a fertility or agricultural ritual, specifically to Tláloc. As is well known, the sacrifice of children in different forms, particularly children called tlaloques, was associated with agricultural fertility rites [33]. In the rites associated with calendrical events among the Mexica, within the 18 months of their calendar known as Atlacahualo and Tepeilhuitl, children were offered to minor gods or tlaloques to attract rain. However, only the children’s hearts were removed, and they were skinned. Therefore, this offering does not appear to have all the characteristics of these offerings.

But in the months Hueytozoztli and Atemoztli, children were offered to the Tlaloques as acts of fertility, by decapitating them and subsequently dismembering them to deposit them in parts or whole, as agricultural ritual acts asking for good harvests and abundance, data that seem to correspond to the characteristics of these sacrificial offerings [33,34]. A third aspect that substantiates and demonstrates the intention and context of the offering is the direction or spatial projection of the offered remains. That is, the arrangement of the bones towards a specific cardinal direction, hence their meaning. Particularly the older youth presented his femurs and tibias arranged in an anatomical position pointing towards the south. Furthermore, the skull was on top of the femurs; all this arrangement indicates a deliberate choice of direction with full knowledge of where to go. The cardinal point towards the South is where the Tlaloques go and bring rain. In the dual cosmogony of Mesoamerican thought, the south indicates midday, the zenith, the maximum degree of light, the sun, with a connection to humankind [35]. But it also signifies the maximum degree of human existence and plant cycles; in contrast to the North, which is the most profane and dark direction, associated with woman, midnight, and the minimum degree of vitality. [28,29], [36,37].

A fourth and final aspect that could clarify the meaning of the offering, but which lacks conclusive analysis, is the study of pollen in the sediments found on plates and ceramics where the offering was deposited. Palynological studies in the surrounding areas and bodies of water, with evidence of chinampas near the archaeological sites, demonstrated considerable agricultural activity. Largescale amaranth cultivation was one of the region’s main activities. Amaranth is a highly nutritious food mentioned in the Badianus Codex as being used medicinally for deficiencies and ritually to denote abundance [38-40]. Therefore, the combination of amaranth as an offering with children, in a building dedicated to water and wind, leaves no doubt as to a ritual of fertility and abundance. A particularly interesting aspect is the presence of healthy children in ritual acts, an indicator of a period of social stability [41]. It is also important to note that these scant bone and tooth remains showed no signs of pathology or nutritional deficiency, suggesting they may have belonged to children of high social standing. Since it has been demonstrated that children of the nobility were offered as sacrifices in other Mesoamerican cultures, another possibility is that the majority of the city’s inhabitants were in good health due to an abundance of food-further evidence suggesting a stratified and well-organized society during a period of prosperity.

Conclusion

The excavations, the recorded contexts, and the analysis of the archaeological materials from the Joyita A and Joyita B complexes demonstrate beyond any doubt that they were used for residential purposes. However, despite being integrated into these residential complexes, the circular buildings designated E3 and E4, which have a spiral floor plan, were probably used as family “chapels” or “sanctuaries” that replicated, at a domestic level, the community ritual celebrated in ceremonial circles. Spiral altars have also been found within Guachimontones, specifically in the central altars of circles 8 and 3: “From the center of the platform to the eastern end, the radius is greater than from the center to the northern and southern ends. This is because, at the southeast end of the altar, the wall has a 50 cm cutout that runs from the outside in, modifying the roundness of the altar and giving it a spiral shape. This same modification is present in circle three, which has the same feature in the second level of the altar” [42]. As previously argued, both the spiral architectural morphology and the results of osteological analyses point to the celebration of domestic rituals dedicated primarily to the supernatural forces of wind and water.

The presence of this spiral pattern in the residential buildings at Guachimontones is highly significant, as it demonstrates the practice of an institutionalized religion in which families enacted community rituals on a domestic scale. It is also significant that the few burials found in residential units are associated with these structures. Thus, the circular buildings serve as domestic chapels or sanctuaries that are representative of the Teuchitlán tradition’s worldview. In conclusion, we can say that the skeletal remains are a ritual offering of an agricultural nature, intended to promote fertility, offered to Tláloc/Ehecatl or equivalents of his elemental forces, and perhaps to Quetzalcóatl (in Nahuatl), to attract rain and provide abundance. Therefore, offerings containing parts of children, such as feet, heads, and teeth, are placed, perhaps as offerings to the Tlalloques, or gods who bring water. This is assuming the meaning remains consistent within Mesoamerican cosmogony.

Acknowledgment

We want to express our deepest gratitude to Dr. Phil C. Weigand† for his many passionate teachings, for giving us the opportunity and trust to be part of this project. (May he rest in peace). We also extend our heartfelt thanks to Josafat Alberto Betancourt for his dedication and interest. (May he rest in peace). Finally, we thank the Government of the State of Jalisco, Mexico, for their interest in and funding of this project (PAT) until its completion.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest between the authors.

References

- Hillson S (2005) Teeth. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. (2nd edn), Cambridge University Press, England.

- Brothwell DR (1987) Unearthing bones. The excavation, treatment and study of human skeletal remains. Madrid, Fondo de Economic Culture.

- White TD, Folkens PA (2005) The human bone manual. Elsevier Academic press, Netherlands, pp. 127-152.

- Turner CG, Turner JA (1999) Man corn, cannibalism and violence in the prehistoric American Southwest. The University of Utah press, Salt Lake City, USA.

- Lumholtz C (1946) Unknown Mexico. Five years of exploration among the tribes of the Sierra madre occidental; In the Tierra caliente region of Tepic and Jalisco, and among the Tarascans of Michoacán, Publications Blacksmiths, México, 2.

- Weigand P (1992) Ehécatl: First supreme god of the west? In: Bohem B, Weigand PC (Eds.) Origin and development of civilization in Western Mexico: homage to Pedro armillas and angel Palerm, The College of Michoacán, Zamora, Spain.

- Avendaño EOC (2008) Tequila valley: Time, gods, and social order. Studies from Jalisco, pp. 56-71.

- Weigand P, Ibí

- Lumholtz, op. Cit.

- Weigand P (1994) The architecture of the Teuchitlán Tradition of Mexico's occidente. In: Palafox RA (Ed.), Major transformations in Western Mexico, University of Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico, pp. 59-88.

- Camberos LLM, Esquivias MM (2003) Archaeological investigations in La Higuerita, Tala. Journal of the Mexican History Seminar 4(1): 11-33.

- Villegas JG (1976) Archaeological rescue of the Tabachines subdivision, Zapopan, Jalisco. Guadalajara: National institute of anthropology and history.

- Weigand P, Weigand AGD (2003) The Teuchitlán tradition. Excavation seasons 1999-2000 at the Guachimontones. Journal of the Mexican History Seminar 4(1): 35-59.

- Mestas L, Montejano, Ibid.

- Villegas JG, Ibí

- Rizo EG (2021) Ehécatl and the rain deities in the Tequila region, Jalisco during the epiclassic and postclassic periods (600-1521 AD). Chicomoztoc Magazine 3(5): 77-106.

- Tapia G, Carmen MD (2011) Presence of pre-Hispanic symbols: Fire, air, earth and water, in the plastic work of Diego Rivera, Bachelor's thesis in visual arts, Michoacan University of San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, Michoacan, Mexico.

- Tapia GM, Ibí

- Mestas L, Lorenza (2004) The exchange of shells in western Mexico during the late preclassic and early classic periods. In: Williams E (ed.), Strategic goods of ancient western Mexico, The college of Michoacán, Zamora, Michoacán, Mexico.

- Espinosa PG (2018) Animals and symbols of the wind among the Nahua. Mexican Archaeology 152, 40-50.

- Taube KA (2018) Origins and symbolism of the wind deity in Mesoamerica. Mexican Archaeology 128: 34-39.

- Weigand PC, Williams E (1997) Adela Breton and the beginnings of archaeology in Western Mexico. In Relations 70, Spring, The College of Michoacán, Zamora, Mexico, 18.

- Broda J (2016) Water in the worldview of Mesoamerica. In: Ruiz JLM, Licea DM (Eds.), Water in the worldview of indigenous peoples in Mexico, Mexico City: Ministry of environment and natural resources, pp. 13-27.

- Austin AL, García EV (2018) A concept of god applicable to the Mayan tradition. Mexican Archaeology 128: 23-24.

- Weigand, P, Weigand AGD. Op. cit.

- Arana IN, López JB (2010) Comprehensive anthropological analysis of the bone remains of the archaeological zone of Los Guachimontones, Jalisco during its period of splendor in the late formative period (370BC-130AD). Ecumene 2(1): 35-91.

- Austin AL (1996) Human Body and Ideology. UNAM, Mexico.

- Austin AL (2004) The composition of the person in the Mesoamerican tradition. Arqueología Mexicana 11(65): 30-35.

- Pablo EG (2005) Hands and feet in Mesoamerica. Segments and contexts. Mexican Archaeology 13(71): 20-27.

- Portilla ML (1980) Toltecayotl, Aspects of Nahuatl culture. Fondo de Cultura Econó

- Valdés JAG (2008) Dental anthropology in populations of Western Mesoamerica. National Institute of Anthropology and History, pp.277.

- Rodríguez ZL (2004) The ritual use of the body in Pre-Hispanic Mexico. Mexican Archaeology 11(65): 42-47.

- Graulich M (2003) Human sacrifice in Mesoamerica. Mexican Archaeology 11(63): 16-21.

- Torres YG (2003) Human sacrifice among the Mexica. Mexican Archaeology 11(63): 22-23 y 40-45.

- Johansson P (2002) Pre-Columbian Nahua funerary rites. Secretariat of culture of Puebla/ Government of the state of Puebla, Mexico.

- Portilla ML (1958) Rites, priests and attire of the gods. National Autonomous University of Mexico, (1st edn).

- Cuestas MES, González JAT (2010) A vision of life and death in pre-Hispanic Mexico. Mexican Archaeology 17(102): 18-23.

- Stuart G (2005) Wetland agriculture in ancient Western Mexico: New perspectives on the pre-Hispanic past. In: Williams E, Weigand P, Mestas LL (Eds.), The College of Michoacán, Mexico.

- Cruz DL (1991) Martin libellus de medicinalibus indorum herbis. Aztec manuscript 1552, According to the Latin translation by Juan Badiano, Spanish version with studies and commentaries by various authors, FCE/ Mexican Social Security Institute, facsimile, Mexico.

- Lozano AMV (2016) The divine bodies. Amaranth, ritual and everyday food. Mexican Archaeology 23(138): 26-33.

- Reyes MEP, Hernández PO (2008) Evaluation of child growth in Mesoamerican series: Proposal of an analysis. In: Licón EEG, Hernández P, Morfín LM (Eds.), Current trends in archaeology in Mé INAH, Mexico, (1st edn), pp. 79-106.

- Herrejón J, Joyita L (2008) A first approach to the domestic spaces of the Teuchitlán Tradition, in Teuchitlán Tradition. In: Weigand PC, Beekman C, Esparza R (Eds.), The College of Michoacán and the Secretary of Culture of the State of Jalisco, Mexico, pp. 63-87.

© 2025 Mxolisi Gwala*. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)