- Submissions

Full Text

Archaeology & Anthropology:Open Access

Geo-Economic Impacts of the Wind Energy Matrix on Traditional Communities in Northeast Brazil: On a Just and Popular Energy Transition

Cristiano Cassiano de Araújo*

Professor of the Academic Department of Geography, Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Bahia, Brazil

*Corresponding author:Academic Department of Geography - Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Bahia, Bahia state, Brazil

Submission: September 05, 2025; Published: December 01, 2025

ISSN: 2577-1949 Volume5 Issue4

Abstract

This article examines the socio-environmental and geo-economic impacts of wind energy expansion in Northeast Brazil, particularly in Bahia’s traditional communities. Based on a literature review and recent data on wind power territorialization, it discusses how wind farms have altered land use, caused displacement, and reshaped family farming systems. These processes directly affect food security, water resources, and the livelihoods of quilombolas1, Indigenous, and Fundo/Fecho de Pasto groups2. While wind power is promoted as a clean and renewable source, its current implementation reproduces historical inequalities, intensifies socio-spatial conflicts, and raises questions about environmental and social justice. The study argues that energy transition can only be fair and sustainable if it ensures meaningful participation of local communities, respects territorial rights, and establishes public policies to mitigate impacts, secure social benefits, and safeguard ecological integrity.

Keywords: Wind energy; Renewable energy; Traditional communities; Family farming; Socioenvironmental impacts; Food security; Territorial conflicts; Environmental justice; Energy transition; Northeast Brazil

Introduction

According to the article published by [1], among a series of data collected on the wind energy sector in the state of Bahia, Northeast Brazil, in 2023, one figure drew particular attention: 72.8% of the wind power capacity granted by the state was controlled by companies with foreign participation, with only 27 corporations controlling the 577 plants approved by ANEEL3[1]. Also points out that, as of 01/01/2024, 183,315.33 hectares of land had already been allocated by the state government for the exploitation of the wind energy market4. Although legitimized by the climate and environmental crises, as well as by the state and regional wind potential [2], the sector has, in recent years, revealed a series of contradictions inherent to the dynamics of this territorialization process within the state and the wider Northeast region. These contradictions have generated multiple socio-spatial impacts due to the installation of these projects. Among them, the presence of such structures in Brazilian traditional communities, such as Quilombola groups, Fundo and Fecho de Pasto communities, and different Indigenous peoples stands out, since it reproduces historical inequalities in land income distribution.

1 They are members of ethno-racial communities in Brazil, descendants of

enslaved people who fled the slavery system, forming communities (quilombos) to

guarantee their freedom and survival, and maintain a cultural identity, traditions

and ties to the land.

2 They are traditional people from western Bahia who live in an integrated manner

with the Cerrado (a Brazilian biome with characteristics like African savannas) and

Caatinga (an endemic Brazilian biome located in part of the states of the Northeast

region), using collective lands for raising free-range cattle and supporting their

families through subsistence farming, extractivism, and fruit gathering.

3 Portuguese acronym for the National Electric Energy Agency

4 Equivalent to 1.833 soccer fields.

This shift primarily occurs through the transition from small-scale agricultural production to industrial uses, a dynamic characterized by the predominance of foreign capital, surpassing even the performance of national companies [1]. This scenario is further reinforced by the absence of compensatory or mitigating actions, including indemnifications required during the Environmental Licensing process, which have often not been implemented in these affected communities [1-5]. Thus, the focus of this article is, based on the substantial body of evidence reporting and studies how these ventures affect traditional communitiesparticularly those sustained by family farming [6-8]-to propose a theoretical-conceptual debate on these impacts, which are directly linked to another sensitive theme in Brazilian Geography: disputes over territories and natural resources [1,2,4,9]. In this sense, the article demonstrates that this energy matrix generates a wide range of conflicts that even put into question the dominant discourse surrounding “clean energy” produced by wind farms. The energy may be clean, but the practices operating behind the scenes are not. Considering the bibliographic references to be used here, in our view, it is possible to correlate this energy matrix and its impactsarising from territorial and natural resource disputes [1,2]-to the proposal of a research agenda in this field.

Through a bibliographic review with an exploratory approach, the article examines how the direct and indirect impacts of wind energy on traditional communities, especially in the Northeast region, and notably in the state of Bahia, may contribute to the reduction of farmland devoted to food crops that supply markets, fairs, and supermarkets in towns located within the areas of these projects. This, in turn, hampers not only the geo-economic production of family farming but may also reduce the quality and availability of products in these commercial spaces, creating problems in the field of food security in these towns. Above all, the loss of productive control of traditional territories and the deterritorialization of their populations corroborates the concept of socio-spatial impacts as a geo-economic dimension. Therefore, the objective of this article is to develop, through a qualitative approach, a dual analysis. First, it aims to review contemporary Brazilian literature on the impacts of the wind energy matrix on the agricultural production of traditional communities. Second, it seeks to reflect, based on the theoretical and conceptual discussion outlined above, on possible pathways to propose, for a country of continental dimensions such as Brazil, an energy transition model that is both fair and capable of generating real social gains.

The wind energy sector in Brazil and in the northeast region: Brief considerations5

Wind energy has been used for human activities since the dawn of civilization, such as in grain milling and water pumping [10], with notable examples in the Netherlands, where, between the 17th and 19th centuries, windmill technology was used for land drainage [11]. In the post-Industrial Revolution period, at the end of the 19th century, traditional wind energy went into decline, being replaced by fossil fuels [12]. However, the expansion of electric grids encouraged the adaptation of mills for electricity generation, leading to the development of the first wind turbine in 1888 [11]. In the mid-1was, during the oil crisis, concerns about the effects of environmental degradation were raised at events such as the Stockholm Conference of 1972 [13], reinforcing the global search for renewable energy sources. The history of wind energy in Brazil began in 1992, when the first wind turbine was installed on the island of Fernando de Noronha, state of Pernambuco. However, it was only in 2002, with the creation of the Incentive Program for Alternative Sources of Electric Energy (Proinfa6), together with specific energy auctions, that this sector truly gained strength and established itself as one of the main options in the national energy matrix [14].

Since the 2000s, growth has been significant: in 2016, Brazil had an installed capacity of 10 gigawatts, and by 2020, this figure had reached 20 gigawatts [15]. Today, wind power is the second largest source of electricity generation in the country, a result of factors such as technological cost reduction, government support, and efforts to invest in renewable and sustainable sources. Although considerable advances have been made, the sector still faces challenges, such as irregularity in energy generation and issues related to transmission infrastructure. Nevertheless, the future remains highly promising, especially due to the development of offshore wind farm projects already under regulation and the vast wind potential in the Northeast region-particularly in Bahia, Rio Grande do Norte, and Ceará-as well as in the South, in states such as Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina [16]. These investments are helping Brazil consolidate its position as a global leader in wind energy. In recent years, this energy source has become essential during periods of low rainfall, when hydroelectric reservoirs show limited capacity for energy production. At such times, wind turbines and wind farms supply the demand and provide both balance among energy sources and an essential energy supply for all sectors of society.

This is a fact. However, as the popular saying goes, “you cannot reap two benefits from the same sack,” and unfortunately, this metaphor reflects the duality of the sector in Brazil: the environmental impacts generated during the installation, maintenance, and operational phases of these projects vis-à-vis the benefits they bring. Therefore, the development of this sector requires caution so that its benefits are not achieved at the expense of others’ suffering. As highlighted in current literature, particularly [17], the consequences vary in scale and intensity. Impacts range from health problems, such as noise pollution, one of the leading causes of depression among people living near wind turbines and wind farms, to alterations in the behavior of wild animals, soil fertility changes, and even transformations in the sociability of rural communities. Thus, the installation of wind turbines and farms in Brazil, particularly in the Northeast-the region with the highest wind potential for energy generation [2]-directly impacts the agricultural production of traditional communities such as family farmers, Quilombolas, Fundo and Fecho de Pasto communities, and Indigenous peoples. According to Pereira [1], the main impact involves shifting land use from small-scale agricultural production to industrial purposes. The consequences extend to the local economy and regional scale, eventually acquiring territorial dimensions across all the states of the Northeast region.

5 The Brazilian Northeast is made up of nine states: Alagoas, Bahia, Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Piauí, Rio

Grande do Norte, and Sergipe. The region’s main wind farms are located in the states of Rio Grande do Norte, Bahia,

Ceará, and Pernambuco.

6 Acronym in Portuguese.

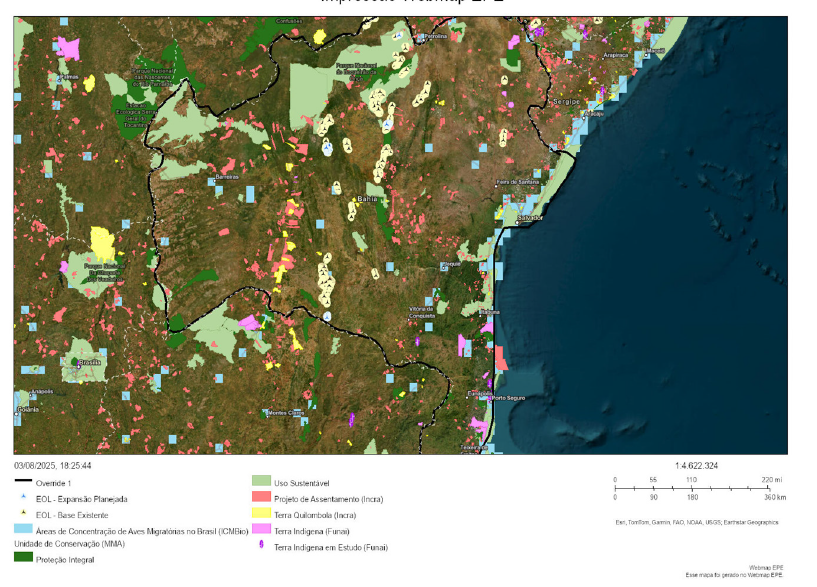

To better understand this context, especially in the state of Bahia, the following exercise was undertaken: satellite images from the Webmap of the Energy Research Company (ERC) were used. This tool, in a very illustrative way, provides a menu option to identify, through layers, the locations of different communities living near wind turbines and wind farms, expanding the possibilities of visualizing potential socio-spatial impacts. This exercise revealed many rural settlements from the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA7), most of them resulting from public policies on Agrarian Reform-an uncontested synonym for “family farming.” Based on Pereira’s recent work [1,2], which highlights other issues related to wind farms, and considering that Bahia is the second state with the highest number of turbines connected to this energy matrix, an analytical framework was outlined within Economic Geography. It opens a research agenda in the field of environment and humanities: namely, understanding how the impacts caused by wind farms can override land use dedicated to family farming in favor of industrial use. This, in turn, affects family farming production and, more specifically, the agricultural products marketed by traditional communities in local fairs, markets, and supermarkets in the interior of Bahia. Although speculative at this point, this perspective presents great exploratory potential.

Socio-environmental impacts of the wind energy matrix in Brazil and specifically in the Northeast Region and in the State of Bahia

The impacts of the wind energy matrix are diverse and farreaching, especially regarding their spatial and scalar scope. In this section, the main impacts are identified in relation to water resources; health risks and threats to physical integrity; damage to ecosystems; risks and potential socio-environmental impacts of offshore wind farms; and damage to artisanal fisheries. Afterwards, the focus shifts to the impacts on family farming, which, in Brazil, is defined in contrast to agribusiness. Unlike the large agricultural conglomerates that specialize exclusively in exporting commodities, family farming is responsible for supplying more than 70% of the food consumed by Brazil’s 213 million inhabitants. The impacts on water resources are broad and multifaceted, as highlighted by several studies [6]. Shows that interventions such as soil compaction and the construction of access roads to wind farms alter the hydrostatic level of aquifers and reduce natural recharge [18]. Emphasizes that earthworks and concrete foundations for turbines cause soil impermeabilization, aggravating groundwater scarcity [7]. Reports that the installation of wind farms, such as the Formosa Wind Farm, resulted in the burial of interdunal lagoons and a reduction in water volume, affecting both fishing and community access to water [19].

Point out the intensive extraction of groundwater during construction processes, which reduces regional water availability [8]. Adds that paving and compaction in aquifer recharge areas hinder natural renewal and alter static groundwater levels [20]. highlights indirect impacts such as vegetation removal and landuse changes, which raise local temperatures, increase evaporation, and affect regional hydrological dynamics. The presence of wind farms can trigger several health problems and physical risks for local populations. Dust generated by heavy vehicle traffic and construction machinery increases the risk of respiratory diseases. The intense flow of these vehicles during construction also increases the risk of accidents and fatalities, altering everyday life, particularly for women and children, who face greater risks when attending school or engaging in outdoor activities. Families that rely on fishing and agriculture experience reduced income and food supply, compromising food security and sovereignty. Noise pollution generated by wind turbines undermines the wellbeing of residents, causing discomfort and noise-related illnesses. Furthermore, companies responsible for the projects impose restrictions on territorial use and access, creating a permanent system of surveillance that limits residents’ autonomy.

The installation of wind turbines, which form wind complexes and power plants, require construction activities that irreversibly alter coastal environmental dynamics. Research on the socioenvironmental impacts of wind farms in northeastern dune fields identifies effects such as deforestation and burial of fixed dunes; filling of interdunal lagoons; cutting and filling of fixed and mobile dunes; addition of sedimentary material for soil impermeabilization and dune stabilization; and removal of fruit trees and native species. These interventions fragment ecosystems and alter their dynamics, with both short- and long-term environmental consequences. Problems such as erosion control, changes in hydrological flows, loss of biodiversity, and even contamination of dune aquifers have been reported. For local communities, this translates into changes in land use, intensification of environmental conflicts, and growing dependency on corporate management, which undermines traditional knowledge and practices. In Brazil, in addition to weaknesses in environmental impact studies, none of the planned offshore projects has yet considered the obligation of free, prior, and informed consultation with local populations, as established by ILO Convention 169. International experience shows that offshore wind farms generate environmental impacts such as vibration, electromagnetic fields, high maintenance costs, soil degradation, and disturbances to benthic organisms.

7 Acronym in Portuguese.

These effects are documented even when installations are located far from the coast. In Brazil, however, unlike Europe, offshore projects are being planned very close to the coast, under the logic of green hydrogen competitiveness and cost reduction. In Ceará, for example, projected distances reach only 3km from the shoreline. As of August 2023, the state planned approximately 3,921 offshore turbines in 23 mega-projects, overlapping with multiple uses of marine territories [21]. This coastal zone lies within the continental shelf, an area of shallow depth typical of tropical seas, associated with high biological productivity and socio-diversity. In Ceará, the shelf extends on average 63km from the coast, serving as the main fishing area for artisanal communities. Offshore projects in these areas pose explicit threats to artisanal fishing, a structuring activity for coastal livelihoods, now at risk due to the real threats and uncertainties in play. Continuing to talk about the state of Ceará, 78.17% of the maritime fishing fleet consists of sail-powered vessels, which dominate artisanal fishing. Tropical seas have low catch volumes but high species diversity, making sail propulsion a viable and cost-effective method for harvesting small quantities of multiple species over large areas.

The privatization of extensive marine territories for wind turbines would undermine this practice, which depends on the collective use of the sea. Artisanal fishing accounts for 64.66% of all landed fish production in Ceará, estimated at 15.5 thousand tons [21]. More than 300 coastal communities depend directly or indirectly on this activity. Exclusion zones or turbine overlaps in artisanal fishing areas would render this practice unfeasible, jeopardizing food security and local economic autonomy. Fish supply across the state would also be affected, along with regional tourism, as the “toothpick effect” of wind turbines alters coastal landscapes and limits aquatic sports, both important sources of income for communities and municipalities [22]. Marine wind turbines, which are larger than their onshore counterparts, require extensive logistical operations, impacting wetlands such as beaches, estuaries, reefs, and mangroves. These areas are vital for marine biodiversity and provide ecosystem services such as carbon sequestration, coastal protection against erosion, and storm mitigation-benefits critical to both local communities and broader society.

Impacts of wind energy on agricultural production in traditional communities

Figure 1:Location of wind towers and wind farms in the state of Bahia.

As discussed in the previous section, the construction of wind farms can negatively affect environmental resources, and consequently, the agricultural production of traditional communities, especially in regions with high dependence on water for farming and fragile hydrological systems, such as the semiarid Northeast. The installation of wind farms often results in the loss of productive land and decreased yields, since alterations in water regimes and contamination reduce the availability of water for irrigation and livestock. Land tenure contexts are also impacted, as the presence of wind projects generates land conflicts, particularly in traditional communities where territory has deep cultural and economic significance. Reduced farmland and productivity can trigger rural exodus, forcing families to seek alternative livelihoods elsewhere. Satellite image analysis (Figure 1)8 revealed that the installation of wind farms can lead to the loss of territory and livelihoods for Quilombola groups, Indigenous peoples, and smallholder farmers. Changes in land use and forced displacement contribute to social and cultural disintegration, undermining traditions and ways of life. These processes are often marked by conflict, especially in the absence of dialogue or effective participation of communities in planning and implementation [5].

Therefore, despite wind energy being labeled a clean and renewable source, its deployment must be preceded by thorough environmental impact assessments and ensure the active involvement of affected communities. Transparent dialogue and participatory planning are essential to guarantee that the benefits of this technology do not override the basic needs and quality of life of local populations. According to Almeida and Resende [23], the productive profile of traditional communities characterizes them as family farmers-that is, Quilombolas, Indigenous peoples, and others survive primarily through of the subsistence plots. In this context, Silva [8] studied the impacts of wind power on small farmers in Pernambuco’s Agreste region, highlighting negative socio-spatial consequences such as desterritorialization, rural exodus, health problems, noise pollution, changes in soil fertility, and shifts in community sociability. Using semi-structured interviews, direct observation, and narrative analysis, Silva demonstrated how these impacts undermine quality of life and local livelihoods. Although based on the Pernambuco semi-arid context, these examples are like those in Bahia, Piauí, and Paraíba states. Introduced the concept of environmental injustice, emphasizing how marginalized, lowincome, and politically weaker populations are disproportionately affected by the environmental impacts of public and private projects.

He argues that capitalist accumulation often transfers environmental costs to vulnerable communities, while economic benefits concentrate among privileged groups. This disparity results from locational decisions and public policies that prioritize economic interests over local well-being [24]. Also stresses that environmental injustice involves not only physical damage but also political and social exclusion, as affected communities often lack a voice in decisions impacting their territories. This perpetuates historical inequalities and heightens vulnerability. In the wind energy context, rural populations face forced displacement, loss of access to natural resources, and health impacts, while profits flow to corporations and investors. For Acselrad [24], social struggles must be “environmentalized,” meaning that social movements should incorporate environmental claims into their agendas. Environmental justice should thus guide fair distribution of costs and benefits, respecting local livelihoods and rights. examined distributive conflicts and the “ecology of the poor,” highlighting tensions between natural resource access and capitalist-driven productive activities.

He argues that distributive conflicts are inherent to development models, as different social groups have diverging interests regarding nature’s exploitation. Wealthier sectors pursue profit, while marginalized groups-directly dependent on natural resources-suffer environmental degradation, territorial loss, and restricted access to commons [25]. Advocates recognizing the “ecology of the poor” as a resistance practice, where marginalized groups, though lacking economic or political power, mobilize to defend their territories and ways of life. These struggles are not abstract but grounded in survival and cultural continuity. To deepen the geographic connection, Rogério Haesbaert [26] defines deterritorialization as the loss of spatial references, which disrupts community relationships with their land. It encompasses not only physical displacement but also cultural and symbolic disconnection. This is evident in regions where wind farms, dams, or infrastructure projects transform local landscapes, eroding collective identity and organization [27]. Analyzing wind projects in Caetité (Bahia), demonstrates how land leasing contracts and “privatization of the winds” are embedded in broader processes of land financialization and foreignization.

She argues that despite being marketed as sustainable, wind energy is tied to practices subordinating territories and populations to financial capital. Contracts often favor corporations, binding land use for generations, restricting local mobility, and altering productive activities. Traldi links this to land grabbing and green grabbing, where land and natural resources are appropriated under the guise of environmental sustainability but reproduce inequalities and dispossession. Although wind power contributes to clean electricity, its impact on traditional communities highlights the urgent need for justice-oriented approaches. Genuine sustainability requires transparent dialogue, participatory governance, and respect for community rights. Otherwise, wind projects risk perpetuating social and environmental inequalities, despite their “green” label.

8 EOL - Blue: planned expansion for the installation of new towers and wind farms.

EOL - Yellow: existing and operating towers and wind farms.

Blue Rectangle: areas of concentration of migratory birds in the state of Bahia.

Dark Green Rectangle: Conservation Units of the Ministry of the Environment for Full Protection.

Light Green Rectangle: Conservation Units of the Ministry of the Environment for Sustainable Use.

Red Rectangle: settlement project for Agrarian Reform.

Yellow Rectangle: Quilombolas lands.

Pink Rectangle: Indigenous lands.

Towards a research agenda

It is well known that the Northeast is the Brazilian region whose geographic location most favors the installation of wind farms, given its strong and constant coastal winds. This natural feature has allowed the region to secure a privileged position in the national ranking, becoming the country’s largest producer of wind energy, responsible for more than 90% of Brazil’s installed capacity [2]. However, alongside technological developments and regional growth, the implementation of wind farms has significantly affected traditional communities. The negative impacts are manifold and occur in diverse dimensions. They include threats to water security-understood as the guarantee of sufficient water quantity and quality for human needs-and other environmental problems such as: the effects of turbines on fauna, where blades cause bird and bat collisions, altering migratory routes; vegetation removal and soil disturbance for wind farm installations, leading to erosion; sediment accumulation in riverbeds, streams, and reservoirs; microclimate changes affecting hydrological balance and cycles; constant noise, undermining both physical and mental health; visual impacts, as turbines alter the natural landscape; and territorial disputes, since proximity to traditional communities generates conflicts and external control. These issues also affect small farmers, who depend on secure access to land and water [8,24,25,27].

When transnational companies establish themselves, communities often receive no prior information about these installations. This lack of transparency breeds conflict and feelings of neglect. Communities are pushed away from their territories, losing their identities through restrictions on spaces where they live, work, build their histories, and maintain traditions [28]. Depending on the emphasis, such processes may be described as forms of desterritorialization: economic (relocation), cartographic (overcoming distances), “techno-informational” (dematerialization of connections), political (crossing of state borders), and cultural (symbolic-cultural uprooting). As Haesbaert [26] argues, these processes are often simultaneous: the economy becomes multilocalized in overcoming distance barriers; instantaneous connections relativize physical border control; and communities experience uprooting from immediate life spaces. Ultimately, deterritorialization at one geographic scale often entails reterritorialization at another. This distancing from territory, in line with Haesbaert’s [26] perspective, opens an analytical possibility that, in our view, deserves a place in the research agenda on the impacts of wind energy on the economy. Based on the evidence reviewed, wind farms intervene not only in physical-geographic aspects but also in socio-spatial dynamics of the Northeastern environment, particularly in traditional communities engaged in family farming.

These communities include not only family farmers as typically defined in Brazil but also Quilombolas, Fundo and Fecho de Pasto groups, and Indigenous communities-many of which are fully integrated into local economic cycles. As illustrated in the ERC’s GIS map, these communities are often located within areas of direct influence of wind projects. The resulting impacts reduce productivity in this fragile sector. The most traditional space for this agricultural economy is the open-air market (feira livre, in portuguese), central to both economic circulation and community life [29,30]. Over time, environmental pressures from wind projects may affect these markets in two interdependent ways. First, by enclosing land, companies exert territorial control and appropriate spaces once used for agriculture. Second, as farmland is reduced and converted to industrial use, local agricultural production declines. This shift undermines the socio-economic role of openair markets, leading to reduced supply of staple foods, employment, and income for traditional communities. Although hypothetical at this stage, this analytical lens-linking wind power impacts to local markets-has strong exploratory potential for future research. In the Northeast and Bahia, land-use changes driven by wind energy expansion may become limiting factors for economic growth, social development, spatial justice, and even food security.

Considerations for a change proposal

Territorially carried out in this study shows that, although wind energy has been consolidated as a renewable and strategic alternative in confronting global climate change, its disorderly and territorially concentrated expansion - especially in the semi-arid Northeast-has generated significant impacts on water resources and on the livelihoods of traditional communities engaged in family farming. These impacts manifest at the local scale but radiate consequences for regional development, challenging the dominant discourse that automatically associates renewable sources with full sustainability. From the theoretical review and empirical evidence gathered, it was observed that the implementation of wind farms, by altering land use and occupation, compromises aquifer recharge, affects the dynamics of hydrographic basins, modifies microclimatic regimes, and promotes processes of deterritorialization that weaken the productive and reproductive capacities of affected communities. Such processes lead to restricted water access, reduced farmland, loss of functional biodiversity, and weakening of socio-economic networks sustained by fairs, markets, and supermarkets in the towns and regions where wind farms are installed-spaces central to the circulation and valorization of family farming production in the interior of the Northeast.

It is therefore concluded that, for wind energy production to be truly sustainable, it must be anchored in socio-environmental justice criteria and guided by public policies that ensure local community protagonism, participatory territorial management, and compensation for ecological and socio-economic losses. The critical reading developed here affirms that the energy question cannot be dissociated from struggles over land, water, and territory in rural Brazil, and that the advance of the wind energy matrix over productive areas demands permanent vigilance by civil society, academia, and regulatory agencies. Energy may be clean, but its production, to be just, must respect territories, resources, and people. Thus, the wind energy system risks becoming part of the emerging global trade that reproduces neocolonial, imperialist, and neo-extractives logics, where exploitation falls upon the territories of traditional and historically subordinated populations, perpetuating injustices and deepening environmental racism [31]. The persistence of marine and coastal ecosystems, despite the pressures of hegemonic development, is due precisely to the resistance and care practices of people and communities who, in protecting their territories, maintain environmental integrity.

This context, however, points to the possibility of an energy transition that establishes criteria and measures capable of ensuring more equitable conditions for renewable energy production and trade. This means guaranteeing local benefits, mitigating social and environmental impacts, decarbonizing economies, and recovering environmental liabilities to secure social justice, ecological integrity, and respect for human rights. This leads us to an essential question: Is it possible to build a fair and popular energy transition? Justice, in this context, must be understood from the concrete realities of local populations and from the asymmetric relations between the Global North and South. It is crucial that Brazil and other Southern countries do not limit themselves to agendas that prioritize only the replacement of fossil fuels, neglecting the structural issues of land and sea use. Conserving ecosystems and valuing associated ways of life must be at the center of climate policies, conceived through the effective participation of people. Thus, building a just and social energy transition requires strategies that go beyond the purely technological dimension, incorporating social, economic, and environmental aspects in an integrated manner [32]. In this context, the decentralization of energy management emerges as a fundamental axis, as it strengthens municipal autonomy, promotes the integration of renewable sources, and ensures citizen participation in local planning processes.

This closer relationship between public authorities and civil society helps align energy decisions with community needs while connecting them to global sustainability goals [33]. Effective governance is another central pillar of this process, based on the principles of clarity, transparency, and social engagement. Only through democratic and participatory institutions can local interests be articulated with national and international guidelines, consolidating an inclusive and sustainable energy matrix. In this regard, the regionalization of energy policies is essential, allowing for specific incentives for solar and wind energy adapted to the characteristics of each territory [33]. In this sense, and following Chambers’ [33] line of reasoning, Gorayeb and Brannstrom [34] present some alternatives for this context, suggesting the following paths for participatory management of renewable energy resources in Brazil:

1. Public awareness and community engagement: Promote

the inclusion of local communities through information and

education, ensuring that the benefits generated by wind farms

are negotiated transparently and distributed fairly.

2. Consideration of local values: In addition to wind speed, it

is necessary to consider the social, cultural, and environmental

aspects of the regions where wind farms will be installed.

3. Representation of traditional communities: Ensure

that local communities are properly represented in projects,

avoiding negative impacts and psychosocial harm.

4. Consistent rights-guaranteeing policies: Implement

policies that ensure land rights for traditional populations and

compliance with legal regulations.

5. Dialogue between planners and the public: Establish a

dialogue between planners and local communities to assess the

compatibility of projects with existing land uses.

These measures aim to minimize negative social and environmental impacts and promote a more just and sustainable energy transition.

Another essential factor in preventing the impacts on traditional communities in Northeast Brazil from negatively influencing the geoeconomic process related to land and family agricultural production lies in the debate on resistance to wind power, as documented by Dunlap [35] when analyzing the context of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Mexico. He highlights parallels with the situation in Northeastern Brazil, aligning with the discussion proposed by Pereira [1] on the large number of foreign companies present in Brazilian territory: the critical focus on energy neocolonialism [34]. Diagnostics based on international experiences of community resistance, such as in Mexico and India, expanding the South-South comparison, show that issues such as the five previously listed need to be addressed. However, Juaréz-Hernandéz and León [36] observed that the wind energy exploitation model developed in the region predominantly favors companies, concentrating economic benefits and limiting them for local communities. According to the authors, there is a lack of information on land leasing and no prior consultation or guidance for the population, a situation similar to that of the states of Northeastern Brazil, such as Ceará, Pernambuco, Bahia, and Rio Grande do Norte. They also point to the co-optation of community representatives as a business strategy to maximize economic benefits.

This dynamic was categorized by Sauer and Silva Junior [37] as “strategies of repression,” among which the following stand out: (i) political isolation, denying voice and legitimacy to local demands; (ii) co-optation, through the granting of small privileges to grassroots groups or important leaders, often through financial offers, aimed at weakening the social movement; and (iii) repression, with the use of police force, as recorded by Santos [38] in the quilombola community of Cumbe, on the east coast. However, Nóbrega [39] presents some solutions to foster popular resistance to this energy colonialism in the Brazilian Northeast, highlighting the need for a more just, sovereign, and popular energy transition. Among the initiatives mentioned are:

1. Resistance and Social Mobilization: Social movements

and affected communities have been organized to denounce the

impacts of megaprojects and push for change. Examples include

the Borborema trade union pole, the articulation of peoples

of struggle (ARPOLU), and the Seridó Vivo Movement, all in

the state of Rio Grande do Norte, which hold demonstrations,

petitions, lawsuits, and public hearings.

2. Political Demands: Movements such as MAR (Movement

of People Affected by Renewable Energy) are pushing for a

regulatory framework that guarantees the participation of

affected communities in decisions regarding the location and

installation of projects, as well as measures for reparation and

compensation for the damage caused.

3. Alternative Energy Generation Models: The Semi-Arid

Renewable Energy Committee (CERSA) promotes decentralized

energy generation by organized communities. Examples include

the installation of photovoltaic modules for community use and

the creation of the Bem Viver Cooperative, which shares locally

generated energy.

4. Education and Training: CERSA also conducts training

activities on energy transition and generation and distribution

models, seeking to raise awareness and empower communities

to embrace sustainable alternatives.

These actions aim to break the silence of communities, expand their participation in decision-making, and promote energy models that respect human rights, people’s sovereignty, and environmental preservation. Thus, the energy transition must be understood as a multidimensional process that is not limited to the adoption of new technologies but encompasses structural transformations capable of democratizing energy access, reducing inequalities, and ensuring environmental preservation, thereby shaping a pathway to sustainable development in all its dimensions.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that while wind energy has become a strategic pillar in Brazil’s renewable energy expansion, its development in the Northeast-particularly in Bahia-has produced profound socio-environmental and geo-economic consequences for traditional communities. The findings reveal that the territorialization of wind projects often reproduces historical inequalities, displaces family farming, and traditional communities like Quilombolas, Fundo e Feicho de Pasto communities, and indigenous, compromises water resources, and deepens sociospatial conflicts. These outcomes challenge the dominant discourse that equates renewable energy with sustainability, showing instead that “clean” energy can perpetuate forms of environmental injustice and energy colonialism. For wind power to contribute to a genuinely just and sustainable transition, it must be grounded in democratic governance, participatory planning, and robust public policies that ensure territorial rights, equitable distribution of benefits, and effective mechanisms for compensation [40- 47]. Recognizing the agency of local populations, safeguarding ecosystems, and integrating social, cultural, and economic dimensions into energy policy are indispensable steps. Only by placing justice and community sovereignty at the center of the energy agenda can Brazil ensure that the expansion of renewables aligns with broader goals of social equity, ecological integrity, and sustainable development.

Acknowledgement

None.

Conflict of Interest

No Conflict of interest.

References

- Pereira LI (2024) Who controls the wind? An analysis of the territorialization of wind energy companies in the state of Bahia, Brazil. Geography 49(1): 525-550.

- Pereira LI (2021) The territorialities of land foreignization in northeastern Brazil. GeoNordeste Review 32(1): 06-26.

- Ribeiro CS (2021) Winds of Bahia: An analysis of the socio-economic impacts of wind farms in the semi-arid region of Bahia. 308 f. Thesis (PhD in economics)-Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil.

- Rêgo GFP (2024) Landscapes of (In)justice in wind farms in the state of Bahia. 191 f. Thesis (PhD in geography)-Federal University of Bahia, Salvador, Brazil.

- Klingler M, Ameli N, Rickman J, Schimidt J (2024) Large-scale green grabbing for wind and solar photovoltaic development in Brazil. Nature Sustainability 7: 747-757.

- Meireles AJA (2011) Socio-environmental damages caused by wind farms in dune fields of Northeastern Brazil and criteria for defining locational alternatives. Confins-Revue Franco-Brésilienne De Géographie (11): 11-23.

- Tavares GU (2018) Socio-environmental impacts of wind energy generation: Suppression of interdunal lagoons and food insecurity in the Xavier community, Camocim, Ceará, Undergraduate thesis (BA in geography)-Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil, p. 27.

- Silva TAA (2023) Clean energy for whom? Impacts of wind energy production on small farmers in Pernambuco’s Agreste. Mediations 28(3): 1-14.

- Rêgo GFP, Fonseca AAM (2023) Dynamics of wind energy in river basins? A reflection from the perspective of landscape justice. Geoscience Notebooks 18: 1-23.

- Lopez RA (2002) Wind energy. 1st (edn), Artliber, São Paulo, Brazil, p. 156.

- Dutra RM (2008) Wind energy: Principles and technology. CRESESB, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, p. 436.

- Alves AM (2017) Development of a computational application for technical and economic sizing tubular biodigesters. Dissertation (Master's in Energy Engineering in Agriculture)-State University of Western Paraná, Cascavel, Brazil, p. 105.

- Gnoatto H (2017) Analysis of technical and economic feasibility for the implementation of a wind turbine on rural properties in Cascavel, Londrina and Palmas-PR. Dissertation (Master's in Energy Engineering in Agriculture)-State University of Western Paraná, Cascavel, Brazil, p. 79.

- Varella FKOM, Cavaliero CKN, Miguel ARF, Araújo PD, Silva EP (2007) Impact of Proinfra on the equipment industry: The case of wind energy. I Brazilian Congress of Photovoltaic Solar Energy, Brazil.

- Abeeólica (2020) Annual report of the Brazilian wind energy association.

- Cunha EAA, Siqueira JAC, Nogueira CEC, Diniz AM (2019) Historical aspects of wind energy in Brazil and in the world. Brazilian Journal of Renewable Energies 8(4): 689- 697.

- Maciel NGP, Leite RMB, Santos SEB, Júnior JAAN, Costa AM (2024) Processes of vulnerability to wind energy projects in a peasant community in Pernambuco’s Agreste region. Health in Debate 48(1): 133-144.

- Hofstaetter M (2016) Wind energy: Between winds, impacts and socio-environmental vulnerabilities in Rio Grande do Norte. 2016. 160 f. Dissertation (master’s in Urban and regional studies)-Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, Brazil.

- Féd MMM, Pinheiro MVDA (2013) Wind farms in the coastal zone of Ceará and the associated environmental impacts. Geonorte Review 4(13): 22-41.

- Zanella ME, Brasileiro FMG (2019) Surface temperature changes due to land use modifications: Case study of the Malhadinha wind farm area, Ibiapina-CE. In: Gorayeb A, Brannstrom C, Meireles AJA (Eds.), Socio-environmental impacts of wind farm implementation in Brazil, (1st edn), UFC Press, Fortaleza, Brazil, pp. 229-250.

- Faustino C, Tupinambá SV, Meirelles E (2023) Impacts and socio-environmental damage of wind energy in the marine-coastal environment in Ceará. Rosa Luxemburg Foundation Brazil Paraguay.

- Fonseca EM (2019) Diagnosis of artisanal fishing in the area of influence of the port of Mucuripe, in Fortaleza (CE): Subsidies for regional fisheries management. Systems & Management 14(3): 279-290.

- Almeida MWB, Rezende R (2015) A note on traditional communities and conservation units. Ruris 7(2): 85-196.

- Acselrad H (2010) Environmentalization of social struggles: The case of the environmental justice movement. Advanced Studies 24(68): 103-119.

- Alier JM (2007) The environmentalism of the poor: Environmental conflicts and valuation languages. (1st edn), Contexto, São Paulo, Brazil, p. 379.

- Haesbaert R (2004) The myth of deterritorialization: From the “End of Territories” to multiterritoriality. (1st edn), Bertrand Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, p. 395.

- Traldi M (2019) Socio-economic and territorial impacts of wind farm implementation in Caetité (BA) and João Câmara (RN). In: Gorayb A, Brannstrom C, Meireles AJA (Eds.), Socio-environmental Impacts of wind farm implementation in Brazil. (1st edn), UFC Press, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, pp. 265-286.

- Gonçalves CWP (2008) Another Inconvenient truth: The new political geography of energy from a subaltern perspective. Universitas Humanística (66): 327-365.

- Jesus APMD, Lopes MLB, Filgueiras GC, Couto MHSHF, Brabo MF, et al. (2023) Markets and fairs in Brazil: A systematic literature review. Management and Secretarial Review 14(6): 9522-9545.

- Costa SS (2024) Open-air markets: What does research say about this phenomenon in Brazil? Itinerarius Reflectionis 20(1): 1-18.

- Rodrigues JF (2024) Environmental racism: An intersectional approach to race and environmental ISSUES. Journal in Favor of Racial Equality 7(1): 150-161.

- Sovacool BK, Hess DJ, Cantoni R (2021) Energy transitions from the cradle to the grave: A meta-theoretical framework integrating responsible innovation, social practices, and energy justice. Energy Research & Social Science 75(6): 102027.

- Chambers R (1994) Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA): Analysis of experience. World Development 22(9): 1253-1268.

- Gorayeb A, Brannstrom (2016) Pathways towards participatory management of renewable energy resources (wind farms) in northeastern Brazil. Mercator 15(1): 101-115.

- Dunlap A (2019) Renewing destruction: Wind energy development, conflict and resistance in a Latin American context. [S. l.]: Rowman and Littlefield International, London, p. 244.

- Sergio JH, León G (2014) Wind energy in the Isthmus of tehuantepec: Development, actors, and social opposition. Problems of development 45(178): 139-162.

- Sauer S, Junior GLS (2012) Territoriality and the fight for rights. In: National Human Rights Movement et al. (eds.), Human Rights in Brazil 3: Diagnoses and Perspectives. (1st edn), IFIBE, Passo Fundo, Brazil, pp. 127-135.

- Santos ANG (2014) Wind energy on the NE coast of Brazil: Deconstructing "sustainability" to promote "environmental justice". Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung epaper, pp. 1-18.

- Nobrega JAS (2025) Energy colonialism and the Brazilian northeast as a sacrifice zone for the energy transition. In SciELO Preprints, pp. 1-29.

- Barrero FMC, Filho JAS, Freitas HB, Santos JB (2021) The winds of the north and threats to the mountain ranges of the “Sertão” of Bahia. 24th International Conference of the Society for Human Ecology (SHE), Brazil.

- Bezerra MA (2024) Impacts caused by the expansion of wind and solar energy on water availability in a region. 2024. 67 f. Dissertation (master’s in management and Agro-industrial Systems)-Federal University of Campina Grande, Campina Grande, Brazil.

- Bezerra MA (2024) Impacts of the expansion of wind and solar energy on water availability. Brazilian Journal of Management and Sustainability 11(29): 1267-1296.

- Caramel L (2025) Clean energy advances through Bahia, overlapping with territories of traditional communities.

- Catalão I (2011) Socio-spatial or socio spatial: Continuing the debate. Training 2(18): 39-62.

- Gutierrez F (2025) Good wind. The Northeast concentrates 93% of all wind energy in Brazil.

- Marques J, Almeida AWB (2021) Ecocide of the mountain ranges of the Sertã (1st edn), SABEH Publishers, Paulo Afonso, Brazil, pp. 474.

- Proinfra (2025) Incentive program for alternative sources of electric energy.

© 2025 Mxolisi Gwala*. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)