- Submissions

Full Text

Techniques in Neurosurgery & Neurology

Non-Communicating Spinal Extradural Arachnoid Cyst: Rare Case with Review of Literature

Sachin Guthe*, Pravin Survashe, Vernon Velho and Shardul Wargantiwar

Department of Neurosurgery, Grant medical college and Sir J.J. group of hospitals, India

*Corresponding author: Sachin Guthe, Mch Neurosurgery, Associate Professor in Department of Neurosurgery, Grant Medical College and Sir J.J. Group of hospitals, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Submission: February 21, 2018; Published: March 09, 2018

ISSN 2637-7748

Volume1 Issue3

Abstract

The spinal extradural arachnoid cyst is the rare and uncommon cause of spinal cord compression leading to neurological deficit. The aetiology of this extradural cyst is still unclear. They are considered to arise from congenital defects in the dura. Through this dural defect they communicate with subarachnoid space, hence contain the CSF (cerebro-spinal fluid). Most reports describe such cysts communicating with the intrathecal subarachnoid space through a small defect in the dura. Our case is unique because we found obliterated fibrous cyst tract adherent to the junction of nerve root sleeve and the thecal sac, representing probable pre-existing communication of cyst to subarachnoid space which got obliterated over the period of time. Such fibrous communication was considered in literature, but was never been demonstrated. Only one case of non-communicating extradural arachnoid cyst is previously reported in literature, but fibrous tract was not seen. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment modality in symptomatic cases. Surgical excision of the cyst with closure of dural defect is recommended treatment. MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is diagnostic investigation of choice. Hereby we report a case of posttraumatic, non-communicating, lower thoracic region, spinal extradural arachnoid cyst in a young male who presented with lower back pain with paraparesis. Delayed-onset post traumatic extradural arachnoid cyst should be taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis of intraspinal cysts. We discuss clinical features, mechanism, investigations, surgical management and relevant literature.

Keywords: Extradural; Non-communicating; Spinal arachnoid cyst

Introduction

Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst is a rare entity which can cause cord compression. Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst (SEAC) is a rare disease and uncommon cause of compressive myelopathy. SEAC is more commonly found among male patients and during the second decade of their life. SEACs can be found in any location, although mostly reported to be located at mid thoracic to the thoraco-lumbar junction, commonly in a posterior position. SEAC is an out pouching herniation of the arachnoid membrane through a dural defect that may communicate with intradural subarachnoid space. The aetiology of this herniation is still unclear and can be either congenital or acquired. These cysts can result in fluctuating symptoms associated with cord or root compression. The presenting symptoms may include pain, paresthesia, neurogenic intermittent claudication, bowel or bladder dysfunction and variable degrees of spastic weakness. It is assumed that they can be enlarged by subsequent pressure change in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) during exercise and Valsalva maneuversas there is micro-communication between the cysts and the subarachnoid space. Despite the rarity of SEACs, they are important in neurosurgical view because they are surgically curable disease [1].

We report a case of delayed-onset post traumatic (patient had a past history of trauma to back 10 years ago) spinal extradural arachnoid cyst which was surgically excised. In our case obliterated fibrous cyst tract was found adherent to the junction of nerve root sleeve and the thecal sac, representing a pre-existing communication of cyst to subarachnoid space which got obliterated over the period of time.

Case Report

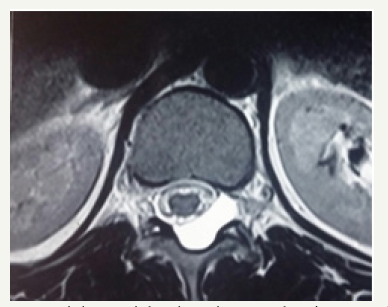

Figure 1a: Pre -operative T1 weighted sagittal MR imagesshowing hypointenseextradural lesion at dll- 12 level. Note the epidural fat capping at the superior and inferior margin of the lesion suggesting its extradural location.

Figure 1b: Pre-operative T2 weighted sagittal MR images showing CSF intensity lesion at d11-d12 level.

Figure 1c: Axial T2 weighted MR images showing extradural arachnoid cyst.

19 year male presented with a history of lower back pain of 6 months duration. It was insidious in onset, gradually progressive with mild weakness of both lower limbs. He had a past history of fall from a tree with sustained injury to back 10 years ago. On examination, he had paraparesis with power (grade 4/5). There were no bladder and bowel disturbances. Other physical findings were not remarkable. MRI dorsal spine with screening of the entire spine showed a small, elongated, well defined CSF signal intensity extradural cystic lesion at D11-12 level suggesting arachnoid cyst. The lesion was compressing the dorsal spinal cord from behind (Figure 1a-1c).

The patient improved symptomatically in post-operative period. Follow up MRI was done 1 month after surgery showed complete disappearance of the cyst (Figure 2).

Operative Findings

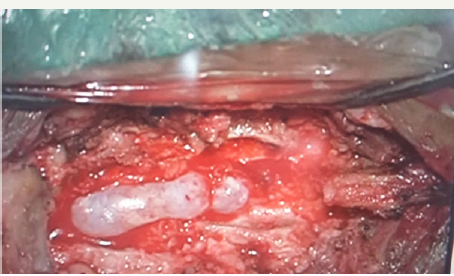

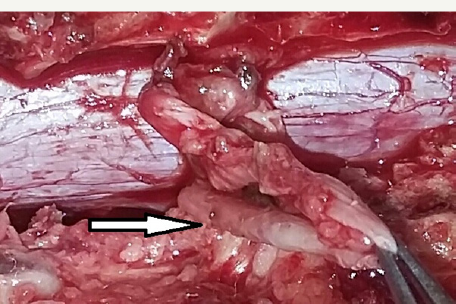

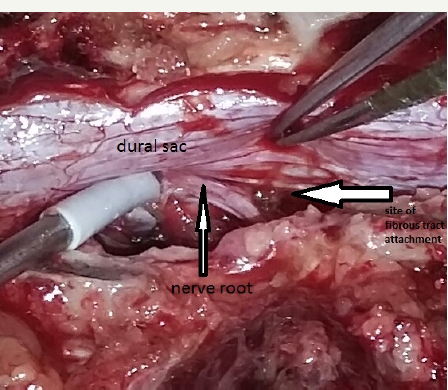

He underwent D11-D12 laminectomy. A small epidural arachnoid cyst of size 3.2x1.8x0.8 cm was noted. It was transparent with well-defined margins (Figure 3). Cyst got easily separated from underlying dura. During microsurgical dissection cyst got ruptured at the weakest point near an upper pole and CSF came out from it. There was a small fibrous tract, which was connecting cyst to the dura at the junction of the nerve sleeve with thecal sac on the left side (Figure 4a & 4b). The cyst was completely excised and fibrous tract was cut near to the dura. Fibrous tract was not patent and no communication to subarachnoid space was identified. There was no dural defect. Valsalva maneuver in a head up position did not reveal any CSF leak from this site. As there was no dural defect, cyst and fibrous tract were excised completely without dural repair. Site of fibrous tract was sealed with fibrin glue as a precaution. Histological examination of the cyst wall demonstrated fibrous connective tissue and some areas were lined by a single layer of flattened cells, consistent with an arachnoid cyst.

Figure 2: Follow up T2 weighted MR Image taken 1 month after surgery showed complete disappearance of the cyst.

Figure 3: Intra-operative photograph showing oval, transparent, extradural arachnoid cyst.

Discussion

Location and clinical features

Spinal arachnoid cysts generally develop in adolescents and twice as many cases occur in male as in female patients. Thoracic cysts usually occur in young adolescents, whereas thoracolumbar and lumbar cysts usually appear in adults in the fourth decade of life. These lesions often arise dorsally and can partially protrude into the adjacent neural foramen. A single cyst can extend over several spinal segments, or multiple cysts with separate dural defects and communicating pedicles can compose one lesion.

Figure 4a: Intra-operative photograph showing fibrous tract (arrow) which was connecting cyst to the dura at the junction of nerve sleeve with thecal sac on left side.

Figure 4b: Big white arrow showing site of attachment of obliterated fibrous tract after excision.

The location of the cyst within the spine and the severity of spinal cord and root compression affect the clinical presentation. Spastic quadriparesis and impaired sensory levels are indicative of cervical cysts, whereas Horner syndrome is a common presentation in patients with cysts that occur lower in the cervical spine. Patients with thoracic cysts tend to present with progressive spastic paraparesis, but back pain is generally uncommon; conversely, patients with lumbar and lumbosacral cysts classically present with low-back pain, radiculopathy and bowel and bladder dysfunction. Overall, motor weakness is usually more predominant than sensory loss. Symptoms can be intermittent and exacerbated by Valsalva maneuvers or gravitational positional forces. Remissions and fluctuation in symptoms have been reported in approximately 30% of cases [2].

Pathological features

The wall of a spinal extradural arachnoid cyst usually consists of fibrous connective tissue with an inner single cell arachnoid lining; however, this lining is sometimes absent on histological examination. Spinal arachnoid cysts have been classified into three major categories: extradural cysts without spinal nerve root fibers (Type I), subdivided into extradural arachnoid cysts (Type IA) and sacral meningoceles (Type IB); extradural cysts with spinal nerve root fibers (Type II); and intradural cysts (Type III). In some cases, an extradural cyst can demonstrate substantial intradural extension. In nearly all cases of Type IA cysts, communication of CSF between the cyst and the intrathecal subarachnoid space through a dural defect has been reported [2].

The case of a non-communicating spinal extradural arachnoid cyst was recently reported. Intra-operatively, the dura was intact and there was no evidence of communication into the intradural subarachnoid space [3]. In our case cyst was non-communicating to subarachnoid space but there was fibrous tract which was adherent at the junction of nerve root sleeve and the thecal sac.

Mechanism of pathogenesis

The exact origin and pathogenesis of Type IA spinal extradural arachnoid cysts remain unknown. A congenital origin has been proposed for these cysts, involving either congenital diverticula of the dura or herniation of arachnoid through a congenital dural defect. The dural sleeve of the nerve root or the junction of the sleeve and thecal sac are the most common sites for these defects, although less commonly the dorsal midline of the thecalsac is involved.

A genetic component in the origins of spinal extradural arachnoid cysts is also suggested by their association in various cases with congenital pigmented nevi, diastematomyelia, multiple sclerosis, Marfan syndrome, neural tube defects, spinal dysraphism, and syringomyelia.

For instance, the loss of tissue elasticity and the decrease in tensile tissue strength associated with Marfan syndrome may be connected with duralectasia in the development of these cysts. The association of spinal arachnoid cysts with arachnoiditis, surgery, and trauma has led some authors to suggest that these cysts more likely arise from acquired dural defects. Spiegelmann et al. reported on a case in which hemosiderin-containing macrophages in the cyst wall caused spastic paraparesis 10 years after craniospinal injury. Active fluid secretion from the cyst wall, passive osmosis of water, and hydrostatic pressure of CSF have all been proposed as possible mechanisms for cyst enlargement. Some authors have postulated that a ball-valve mechanism in the communicating pedicle is associated with pulsatile CSF dynamics and results in cyst expansion. According to this theory, intermittent surges of pressure in the subarachnoid space are communicated to the cyst, and fluid flows into the pouch. When pressure decreases again, the compression of the cyst pedicle inhibits fluid outflow. According to the Laplace law, the cyst body exerts a force on the neck sufficient to close the communication, because its radius and wall tension are greater. These factors then allow further enlargement with persistent CSF pulsations. This ball-valve mechanism has been observed intraoperatively by Rohrer et al. [2].

A possible mechanism for the closure of cyst is that the non- communicating cyst evolved from a pre-existing communicating cyst that initially formed as a result of a small dural defect. Over time, the cyst enlarged and eventually obliterated the communicating channel to the subarachnoid space because of the Laplace law [4]. The closure of the dural defect may be due to the proliferation of arachnoid cells.

Imaging features

Magnetic resonance imaging appears to be effective as an initial modality for diagnosing arachnoid cysts and does not require the intrathecal injection of contrast medium. It can define the anatomical relationship to surrounding structures. The imaging characteristics of arachnoid cysts are similar to those of CSF signal intensity. Epidural fat capping of the lesion at its superior and inferior poles can be seen on sagittal T1-weighted MR images, which further suggests its extradural location. The presence of vertebral body scalloping and expansion of the neural foramina bilaterally from osseous remodelling suggests a longstanding mass effect from the lesion.

Note, however, that MR imaging may not demonstrate a communication between the cyst and subarachnoid space. Historically, routine water-soluble myelography has been used as the initial study and usually has demonstrated a filling defect at the dural diverticula. Filling of the cyst through the communicating pedicle may not always be visualized, however, particularly if the patient is placed prone. The diagnostic study of choice for demonstrating the communication with the subarachnoid space is CT myelography.

Surgical treatment

For asymptomatic patients, conservative treatment with observation is recommended. The mainstay of treatment in patients with symptomatic neurological deterioration from spinal extradural arachnoid cysts is complete excision of the cyst, followed by obliteration of the communicating pedicle and watertight repair of the dural defect to eradicate the ball-valve mechanism. Total excision of the cyst is recommended whenever possible to prevent re-accumulation of the cyst. These cysts can usually be dissected and elevated off of the dura with ease; however, in cases in which dense fibrous adhesions prevent safe separation of the cyst from the dura, a wide marsupialization of the cyst can be performed by resecting the dorsal wall of the cyst and closing the dural defect. Simple drainage of the cyst contents may result in temporary relief only. If the cyst does not communicate with the subarachnoid space, complete excision can be performed without subsequent repair of the dural defect.

Although numerous surgical treatment methods have been proposed, the results of surgery were variable. Preoperative myelomalacia and long duration of symptoms have been implicated as being predictive of poor surgical outcome. Therefore, in delayed cases, surgery may be offered as an intervention with the prophylactic purpose to prevent further neurological impairment rather than a curative management. The operative treatment most commonly advocated has been total excision of the cyst. However, removal may be hazardous and entail the sacrifice of nerve roots with risk of diverse complications including adherence of the cyst to the nerveroots or to the spinal cord [5].

Lee et al. [6] demonstrated that the recurrence of the SEAC was related to the repair of the dural defect and not to the completeness of SEAC excision. To minimize the extent of laminectomy is important to avoid post-operative complications such as kyphosis. With improved diagnostic tools, we can verify the location of communication or dural defect preoperatively and it can help planning tailored laminotomy to avoid multi-level laminectomy and subsequent increased risk of complications. Currently, many surgeons favour the tailored laminotomy and cyst fenestration with meticulousdural repair rather complete resection of SEACs to reduce the complication related to long-level laminectomy [1].

Conclusion

In surgery, repair of dural defects should be done. Tailored laminotomy is better than multi-level laminectomy. Preoperative myelomalacia and long duration of symptoms have been implicated as being predictive of poor surgical outcome. Extradural arachnoid cyst should be considered in the differential diagnosis of all arachnoid cysts of spine.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest

None.

Source of Funding

None.

References

- Choi SW, Seong HY, Roh SW (2013) Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 54(4): 355-358.

- Liu JK, Cole CD, Kan P, Schmidt MH (2007) Spinal extradural arachnoid cysts: clinical, radiological, and surgical features. Neurosurgical focus 22(2): 1-5.

- Liu JK, Cole CD, Sherr GT, Kestle JR, Walker ML (2005) Noncommunicating spinal extradural arachnoid cyst causing spinal cord compression in a child: case report. J Neurosurg 103(3): 266-269.

- McCrum C, Williams B (1982) Spinal extradural arachnoid pouches: report of two cases. Journal of neurosurgery 57(6): 849-852.

- Kong WK, Cho KT, Hong SK (2013) Spinal extradural arachnoid cyst: A case report. Korean J Spine 10(1): 32-34.

- Lee CH, Hyun SJ, Kim KJ, Jahng TA, Kim HJ (2012) What is a reasonable surgical procedure for spinal extradural arachnoid cysts: is cyst removal mandatory? Eight consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 154(7): 1219-1227.

© 2018 Sachin Guthe, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)