- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

Compassion of Military Spouses for their Spouses and from their Spouses: Reintegration Stress, Coping and Military Culture

Tyan Carrico*, Stephen E Berger and Laird Bridgman

The Chicago School, USA

*Corresponding author:Tyan Carrico, The Chicago School, Anaheim, USA

Submission: August 09, 2024;Published: September 20, 2024

.jpg)

Volume16 Issue 2September 20, 2024

Abstract

The reintegration of a spouse who has been deployed can be very stressful on the non-military spouse both during the deployment as well as after their spouse returns home. A major factor that can help or hinder their relationship is the compassion they have for each other. In this study, 15 women spouses provided their perspectives on the compassion they felt for their military spouse and the compassion they experienced from their military spouse. The results indicated that factors such as commitment to the military culture combined with compassion for and experienced compassion from their spouse was related to the stress they felt and the coping mechanisms they used upon their spouses return to the home. Specifically, it was found that the women who reported receiving the least amount of compassion reported the highest level of stress, especially in regard to their place in the home, reemergence of unresolved conflicts, and problems with civilian employment. Those who reported the greatest compassion for their spouse also reported less commitment to the military culture and less need for/use of coping mechanism even though they did not report different levels of reintegration stress, but greater use of alcohol and/or drugs for coping.

Keywords:Spousal compassion; Military reintegration stress; Military culture; Coping styles

Introduction

Deployment prevalence and effect on the family system

Disruption, maturation during separation, loneliness, abandonment have all been found to be difficulties for veterans when reintegrating [1]. There has been a recent shift in researching issues of reintegration, such that four times more literature has been published between the years 2010 and 2015 than the prior ten years. Often, reintegration is portrayed as a time of joy and reunification, but it may actually be a difficult time with increased stress, tension, and conflict between marital, family, friend, and community dynamics. The stress, tension, and preexisting conflicts are exacerbated by deployment-related stresses [1]. Military families have access to substantial external support from the U.S. Government such as health insurance through the Military Health System and TRICARE, home loans through the Department of Veteran Affairs, a GI Bill to help pay for a college degree, life insurance, finding a civilian job, and food assistance [2]. However, food assistance is often provided by the state. This means that military families would be enrolled in state-run programs that are often associated with those below the poverty line. Families may be resistant to utilizing such services as related to the stigma that surrounds them.

The Department of Defense also provides a network of websites dedicated to supporting the military community. Military One Source is one site that offers support to military families [3]. Spouses are able to connect to a call center for immediate support. However, these types of programs are helpful but only in times of acknowledged great stress. This site can also connect family members to more sustained care. However, little information is provided on how long individuals may wait for services, cost, or efficacy of care. Lester et al. [4] reported that emotion-focused actions and attunement by parents to their child’s emotional needs could help mitigate the negative implications due to deployment separation [4]. For military families, a parent’s sensitivity to their child’s emotional wellbeing maybe even more critical than in civilian culture to also combat the repeated separations, worry, fear, and unpredictable changes military children experience. However, it becomes increasingly more difficult for the spouse at home to balance the increase of responsibilities as well as the greater need for attunement with their children.

Preschool-aged children and younger appear to be most sensitive to deployment-related difficulties. It has also been reported that children under the age of 10 often have an increased risk of internalizing symptoms such as anxiety or depression, externalizing symptoms, such as behavioral outbursts, less secure attachment bonds, lessened prosocial behaviors, and greater issues with peers [4]. Older children and adolescents who have experienced deployment separation from a parent have also been found to have an increased risk of engaging in risky behaviors, substance use, and greater internalizing symptoms. Children of military families face a different constellation of stressors than their civilian counterparts related explicitly to deployment. Children of military families face separation from their caregiver compounded with the fear of danger as well as frequent and rapid changes in their role within their family, other relationships, and living situations [4]. These difficulties are likely magnified for the children as they lack developed coping skills or have limited access to external support. Separation from one’s caregiver at an early age can introduce difficulties within attachment relationships [5]. Children of military families may have greater difficulty developing self-regulation skills or adaptive coping skills to manage difficulties. During deployment, the child’s attachment bond with their deployed parent is being disrupted. This disruption leads to less of the positive benefits of secure attachment, such as the ability to survive short separations with little or no fears of abandonment, such as daycare, for example Belsky & Fearon [5].

Within the marital bond, it was reported that there is increased amounts of conflict and lessened capability to collaboratively resolve conflicts. Increased tension and conflict have often been reported to lead to lessened responsiveness or displaced frustration onto the children [4]. This trickle-down effect remains within military families, such that the caregiving spouse experiences greater stress and mental health difficulties due to the requirements of deployment. These difficulties trickle down and have unintended consequences for the children. Utilizing phone interviews and online surveys, Lester et al. studied 301 primary caregiving parents and 150 military parents with children under the age of 10 years [4]. It was found that 71% of families experienced a minimum of two deployments, and 23% of female and 27% of male caregivers qualified for possible alcohol misuse. Results of the study indicate that having at least one parent enlisted in the military resulted in higher levels of depression, marital instability, and PTSD symptoms, and lessened family functioning and problem-solving abilities for the spouse at home.

Deployment specifically was not significantly related to developing depression, PTSD symptoms, parental sensitivity, or alcohol use for the caregivers [4]. However, deployment was negatively correlated with family adjustment, meaning that the greater number and length of deployments predicted greater dysfunction within emotional involvement, problem-solving, communication, marital instability, and overall family functioning. Surprisingly, caregivers with no military experience were found to be at higher risk for clinically significant PTSD symptoms than caregivers who had prior military experience [4]. In regard to the effect on the children, parents of children between the ages of three and five years old reported their children experiencing significantly greater separation and generalized anxiety. Greater parental depression, parental PTSD symptoms, and lessened parental sensitivity were found to be significant predictors of generalized anxiety for children in this age range. Additionally, these parental factors were found to correlate with greater emotional and behavioral problems for the child, such as emotional outbursts and difficulties in peer relationships [4].

Children between the ages of six and ten years old experienced significantly more emotional difficulties [4]. For children within this age range, multiple deployments tended to compound the severity of the negative impact. Overall, greater parental sensitivity to the child’s emotional needs predicted decreased socioemotional deficits in children, whereas greater PTSD symptoms in parents predicted greater conduct issues, peer issues, and other generalized difficulties in the children [4].

Reintegration effects for the service member

Previous research has indicated that psychological health, physical health, the status of employment, housing, finances, level of education, spirituality, and nonspecific functioning difficulties have been found for veterans during reintegration [6]. In short, research has indicated that reintegration is affected by a host of global psychosocial factors that are interconnected. Researchers found there are four key domains in which a service member faces specific needs and challenges within the personal, interpersonal, community, and society as a whole [6].

Stigma regarding mental health services also poses a barrier to reintegration for the service member. The stigma about mental health still heavily persists in Western cultures but appears to be generalized to many countries. In a multi-country study regarding mental health stigma, a trend was found among service members in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand who reported they feared that the members of their unit may lose confidence in them or that they will be treated differently if they sought treatment [7]. Due to this stigma, it is less likely that a service member may seek psychological support following their return home. This stigma may highly affect the success of a service member’s reintegration as they not only struggle to resume their civilian responsibilities but are also saddled with a silent burden that is affecting their thoughts and perception of others.

The Department of Defense (DoD) has significantly increased the availability of treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in response to the growing number of service members returning home with PTSD symptoms [8]. In fact, the DoD and VA have incorporated screening for PTSD symptoms, substance use, deployment-related health concerns, traumatic brain injuries, and sexual abuse while in the military as a common practice. This screening means that these services are becoming more readily available to service members to treat newly acquired difficulties. Additionally, the DoD has implemented hotlines, Family Readiness Officers to help families prepare for deployment, and training for service members and family’s post-deployment [9]. The adaptation of early screening and supportive ancillary services has been increasing and demonstrates there is a growing community around supporting service members with the global impact of reintegration and deployment stress. The early screening helps to identify those who may need more assistance, quickly receive referrals, or have a more difficult time during the reintegration process. Additionally, this information may be helpful to the family as they are informed of possible deployment-related difficulties and can be pointed in the direction of supporting themselves. Based on these findings, it is important to more clearly establish the marital difficulties service members face when attempting to reintegrate back into their families after fulfilling their military obligations.

Reintegration and the spouse

Past studies focused on the reintegration difficulties of military personnel from World War II and Vietnam [6]. The more recent deployments to Afghanistan and Iraq appear to have had a significant impact on not only service members but their families as well. Medical records demonstrate a higher prevalence of mental health disorders in spouses of deployed service members than non-deployed spouses. Allen, Rhoades, Stanley, and Markman reported that the most common stress for the non-deployed spouse has previously been defined as the concern of their spouse’s safety, adjusting emotionally during deployment, and the amount of communication [6]. The researchers studied 300 active-duty Army male service members at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, and their civilian wives that have experienced a deployment in the previous 12 months. Of that sample, the most common length of deployment was 12 months, and the average length of marriage was five years.

Soldiers and their wives responded to a range of questions and surveys assessing each person’s level of stress related to the deployment, amount of combat exposure, overall military experience, marital quality, amount of connection and support, children’s behaviors, and the level of danger perceived around the soldier’s mission [6]. Results indicated that deployed husbands reported most issues commonly related to deployment as “somewhat stressful,” whereas their civilian wives rated those same stresses as significantly more stressful. Specifically, wives reported significantly higher stress levels regarding combat, physical injury, psychological problems, fear of death, reintegration, loneliness, difficulty staying in touch, and the effects on the children [6]. This may be a mechanism of the male service members having more certainty and control of their safety and environment or the Army training the service members received to handle these specific stressors. During deployment, the wife has less perceived control of deployment-related stresses as they are stationed stateside with limited contact leading to experience more stress while their spouse faces a threat. In general, the lowest stress rating reported by the married couples related to fidelity and sexual frustration from both partners.

Meaning that both the deployed spouse and the civilian spouse did not report high levels of concern around their partner remaining faithful, nor did they report a concern of sexual frustration once reunited. Army wives, specifically, reported more stress around being lonely. As a couple, spouses reported combat experience, reintegration, psychological impact, fear of injury and death, and difficulty staying in touch as significant stressors. While the couples endorsed a similar pattern of concern, the service member husbands rated the stress level associated with each concern as “somewhat stressful.” These ratings were significantly lower than their civilian wives’ perceived stress levels [6]. This indicates that the civilian wives at home, on average, tend to experience stressors as significantly more stressful than their service member husband. Also, the service members may have a psychological need to deny/ repress to some degree their experience of their concern about their safety. The most significant stressor reported by both service members and spouses was the impact of deployment on their children. Both spouses indicated their children’s effect was the most severe source of stress of deployment and reintegration [6].

In addition, the civilian wives indicated that loneliness was a significant stressor for them, but the Army husbands in the study did not endorse feeling lonely as a concern. This may be related to soldiers’ interconnectedness while on deployment. When examining spousal coping, it is important to recognize the essential between spouses. The wives’ indicated feeling lonely, while their service member husbands do not. The disconnect may leave the wives’ need for connection left unmet, further pushing the two spouses apart [6].

How the spouse copes with that loneliness before and during reintegration may affect how they act around the service member (i.e., how welcoming and patient they are with the returning spouse). A greater amount of negative communication, frustration from work, and negative attitudes toward the soldier’s mission were associated with greater perceived stress. However, feeling satisfied in one’s marriage and having positive communication resulted in less stress [6]. For the service members’ wives, feeling as if they need more support was correlated with greater stress, but knowing they had support if needed significantly lowered the spouses reported stress. This means that having appropriate external coping mechanisms and having others in a support system likely mediates a significant number of stressors and reduces the feeling of overwhelm the civilian wives endure.

Socially, the perceived need for greater support was correlated with increased stress. However, believing the spouse had support available if needed was correlated with less perceived stress. Surprisingly, being connected to other Army Families was not related to perceived stress [6]. These findings indicate that the support system a spouse has does not need to be connected with the Army or experiencing similar stressors. Instead, the quality and availability of support reduced the wives’ stress levels.

Coping with reintegration for spouse

Most individuals do not strictly adhere to one style of coping, but they may have a prominent style they use the most. In general, EFC and PFC are considered to be active forms of coping styles, whereas AFC is considered a passive coping style. EFC strategies often involve engaging in other activities that distract the individual from engaging or managing the stressful situation directly. In contrast, PFC strategies tend to be more active and result in the individual feeling empowered. The feeling of empowerment can help people grow, mature, and discover new parts of themselves. In stressful situations, when an individual feels something productive can be done, the individual tends to utilize PFC strategies. In contrast, in situations one feels things are out of their control or something they must survive, individuals tend to use EFC strategies. Avoidant focused coping skills have been previously described as maladaptive, allowing for long-term inhibition of growth and the persistence or increased likelihood of clinically significant mental health concerns [10].

The individual who employs PFC skills may anticipate future situations to prepare and orient their behavior to find rewards in a situation, whereas the individual who employs EFC skills react to minimize the impact of the situation after it has occurred. A proactive strategy may interrupt the emotional response to the stressor as it has not had the opportunity to gain greater momentum. By interrupting the stressful situation, the individual can better take the initiative and refocus their emotional energy into a more constructive response [11]. In contrast, some use of avoidant focused coping skills in combination with active coping skills such as EFC or PFC or use of only active coping skills demonstrated a strong and direct influence on post traumatic growth following increased stressors or traumatic experiences. In a study by Romero et al., researchers studied the connection between service members and the impact of coping styles on attachment [12]. The researchers found that service members who reported increased use of avoidant focused coping styles yielded more insecure attachments, alcohol use, and depression. It can be assumed these finding may also be generalized to coping styles of military spouses. Such that increased use of avoidant coping would yield insecure attachment in the military spouse, resulting in increased interpersonal disconnection between the marital unit during reintegration which is a well-researched time of increased overall stress.

Reintegration difficulties can arise as soon as a service member returns home. The time of reunification is often idealized and romanticized as a glorious and joyful moment. In the context of a long journey home, the returning service member may be exhausted, resulting in the spouse feeling disappointed or underwhelmed [9]. Upon reunification, spouses share a kiss for the first time in approximately nine months to a year, which may be awkward or uncomfortable. Spouses reported a common difficulty upon reunification is the immediate shock of seeing how much their loved ones have changed, specifically the children. At first, these changes may be a source of tension [9].

As a couple begins to adjust and re-establish their life as a couple, a shared experience among service members and their spouses may be to feel unwanted, unappreciated, or overact. Additionally, tension may arise around sharing responsibilities, finances, and intimacy [9]. Tips from spouses who have experienced reintegration suggest that clear communication is an integral component of reintegration [9]. Spouses recommend clearly and openly communicating about changes in schedules, routines, responsibilities, and expectations. A commonly reported pitfall was expecting that a service member can intuit what chores they are to complete [9].

The present study

Previous literature has demonstrated that factors pertaining to the service member and their experiences during deployment have a significant impact on the success of reintegration [6]. These factors may include combat exposure, PTSD, or substance use. Additional research has also investigated the impact of environmental factors such as housing, job security, and finance and interpersonal factors, such as marital conflict, domestic violence, and divorce and their influence on successful reintegration. There has been much research on the experience of service personnel in regard to returning from deployment. However, the research has excluded the influence and experience of the spouse. Theoretically, the spouse plays a large role in reintegration as they have the greatest amount of contact with their returning spouse. Additionally, the spouse likely shares a vast amount of the work in the reintegration process as they must modify their routines, readapt and facilitate the service member back into the family system. It seems unquestionable that the compassion that the spouses feel for each other would be a major factor affecting the stress and coping mechanisms that the military service personnel’s spouse experiences. This study simply examined the extent to which the woman, spouse felt compassion for her mate and the compassion she felt in return was related to the stresses and coping mechanisms that she used and whether endorsement of the military culture was related to the stress experienced and coping mechanisms utilized.

Methods

Participants

The participants were obtained from on-line groups (military support groups, Facebook) and had to have been married to a member of the Army, Navy, Air force or Marines who had been deployed at least once and returned home a month or more prior to the study. All of the participants were between the ages of 24-45, and all were women. A total of 15 participants provided ratings of the compassion they felt for their spouse and 16 of the participants provided ratings of their spouse’s compassion for them.

Measures

A. Demographic questionnaire – Participants completed a

Demographic Questionnaire. The demographic questionnaire

asked about such things as ethnicity, age, gender [10-13].

B. Ganz Scale of identification with the military culture

(GANZ) - This inventory was developed by Ganz based on her

conceptualization of the military culture. It consists of eight

statements that address eight core values of the military [13].

The individual indicates their degree of personal endorsement

of the value on a 7-point Likert scale from “Not at All” to “Very

Much.” It has been utilized in several investigations [14-16].

C. Brief COPE inventory (COPE) – Participants were asked

to respond to a 28-item questionnaire to assess the individuals

coping strategies using the brief version of the Coping

Orientations to Problems Experienced Scale (COPE) [17]. It

identifies Emotion Focused Coping (EFC), Avoidant Focused

Coping (AFC), or Problem Focused Coping (PFC). Using a

4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot).

D. Reintegration stress index (RSI) – Participants were

also given a 12-item questionnaire to assess how stressful the

process of reintegration was for the spouses [18]. Participants

were asked to rate how stressful was each situation on a scale

from 1 (“not at all stressful”) to 7 (“very stressful”).

Procedures

After reading the Informed Consent, those who agreed to participate were given the demographic questionnaire, the GANZ, the COPE and the RSI in that order. After completing the questionnaires, they were presented with a debriefing statement and thanked for their participation.

Results

Analyses

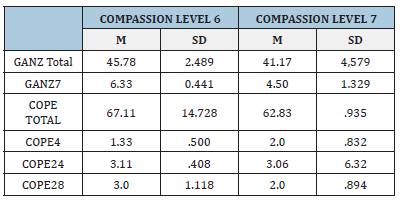

All 15 participants rated their compassion for their spouse in one of the two highest categories. Thus, 9 of them rated their compassion as a 6, and the other 6 rated their compassion for their spouse as a 7. Because of the small N, p levels less than 10 are reported so as not to miss possible differences that a more stringent p level would miss. Despite there being only a one point difference on the Compassion (Likert) scale, that difference was elated to a number of significant differences between the women spouses on GANZ Total score (F(1, 13)=6.445, p=.025), and GANZ7 (F(1,13)=8.989, P=.01) and on COPE Total scores (F(1,13)=4.367, p=.032), and on three of the specific COPE items: COPE4 (F(1,13)=5.20, p -.04; COPE 24 F(1.13)=3.601, p=.057; COPE 28 (F1,13)=3.343, p=.091). The means and standard deviations for these 6 differences are reported in Table 1.

As can be seen in Table 1, those military spouses who reported the greatest level of compassion for their spouse reported a slightly lower level of endorsement of the military culture (GANZ TOTAL), and especially so in regard to the value of “face fear, adversity, and danger. In contrast, a slightly greater endorsement of this military value resulted in slightly less compassion from the women spouses. In regard to use of coping mechanisms, the pattern was a bit more complex. The women spouses who reported a slightly lower level of compassion for their military spouse reported using more coping techniques (COPE Total), and that the specific techniques were learning to live with it (COPE24), and making fun of the situation (COPE 28), but the women spouses who reported the highest level of compassion for their spouse were not coping by learning to live with the situation nor make fun of it, but reported a great use of alcohol or other drugs (COPE4). In combination, the wives who reported slightly less compassion for their military spouse reported a great commitment to the military culture, specifically to face fear, and thus they more easily could use coping mechanisms of learning to live with it as that is what the value system says to do.

Table 1:Means and standard deviations for significant differences for miliary spouses compassion levels on military culture and coping styles.

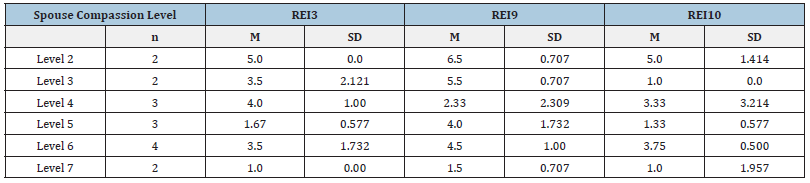

Compassion from spouse

Whereas the women participants rated their level of compassion for their military spouse as either a 6 or the maximum, a seven, they did not report experiencing similar levels of support from their military spouse. Their ratings of what they experienced ranged from a 2 to a 7. These ratings resulted indifferent levels of 3 types of Reintegration Stress. Thus, there were significant differences on Figuring on REI3, Figuring out my role in the house (F(5,9)=…, p=.057), REI9, Resurfacing of unresolved conflicts (F(5,9)=…, p=.038), and REI10 Finding civilian employment (F(5,9)=…, p=.08). Clearly, two of those three stress issues directly relate to the interpersonal relationship, and the third might be a very specific conflict between the spouse and her military husband regarding civilian employment. The Means and standard deviations are provided in Table 2, where it can be seen that the greatest stress was reported by those who indicated they received only a level 2 of compassion from their military spouse, and to some degree, that was also true for levels 3 and 4 of experienced compassion.

Table 2:Means and standard deviations for reintegration stress experienced by spouses according to reported level of perceived compassion from their spouse.

Discussion

Clearly the level of compassion that our participants reported feeling for their military spouse husband and the compassion they felt in return are major factors in the stress these women feel and their coping mechanisms. It is impressive, and a bit surprising that even a 1 level difference in reported level of compassion for their spouse would be associated with different types of coping, and that their own endorsement of the military culture would be a possible mediating factor. Thus, those women spouses who endorsed a greater adherence to the military culture, especially to the value of facing fear, danger, with physical and moral courage, felt slightly less compassion, as high a level as it was (6 out of 7), but apparently feel less compassion because one should be fulfilling the value of facing danger (with moral courage), so one gets less compassion.

These women also reported that most of them did not receive the level of compassion from their spouse that they felt for their spouse. At the lowest level of experienced compassion from their spouse, they reported a great experience of Reintegration Stress, specifically in regard to several aspects of their relationship with their military spouse. Thus, in feeling a low level of compassion from their spouse, the wives experienced a resurgence of unresolved marital conflicts that relate to their role in the relationship and a specific issue regarding employment. Unfortunately, the design of the study did not permit examine more closely the relationships among these variables and other demographic information about the participants.

Clinical implications

Compassion is not a part of the military culture. However, this data indicates that a neglect of the military and of military personnel to appreciate that compassion between spouses can have significant effects of the morale of troops and their family. Thus, programs such as FOCUS should address this potentially crucial aspect of human relationships and work to enhance the level of compassion exchanged between service personnel and their spouses [19]. Individual clinicians working with service personnel should be especially alert to problems related to the level of compassion experienced by service personnel and their spouses and work to enhance this aspect of their patients’ relationship. Another specific value to which clinicians should be alert is the degree of adherence to the military culture as that value system can have profound implications for the relationship of a service member and their spouse.

Limitations and directions for future research

The limitations of the present study revolve primarily around the small sample size. It was not possible to do meaningful analyses of the main variables with other possible factors as the sample size simply did not permit meaningful statistical tests of the main variables in combination with other possible factors. Obviously, future research will want to follow up on the findings and implications of this study. Of course, alternative measures should also be used as the limitations of the measures used here may not have been sensitive to other possible factors related to the stress in the lives and marriages of those married to military personnel. Finally, this study only included women spouses, and there are increasing numbers of men married to women who are in the military, and so they must be studied independently as it cannot be assumed that the experience of the women spouses is the same as men who are married to a woman in the military.

Summary and conclusions

In summary, it was found that women spouses of military personnel who reported high levels of compassion for their military spouse reported greater use of coping mechanism if their level of compassion was not at the highest possible level. They reported a greater endorsement of the military culture, especially facing danger with moral courage and thus, that apparently lowers their compassion just a tiny, but meaningful bit, and so they cope by learning to live with the reality that there is danger for their spouse and stresses that they will experience. It was also found that when they experience a low level of compassion from their spouse that there appear to be significant conflicts (stresses) in the relationship. Based on these findings, it appears that the military and those providing treatment to military personnel and their families would be well advised to be alert to the level of compassion in the relationship of military personnel and their spouses.

References

- de Vibe M, Solhaug I, Rosenvinge JH, Tyssen R, Hanley A, et al. (2018) Six-year positive effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on mindfulness, coping and well-being in medical and psychology students; Results from a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 13(4): e0196053.

- USAGov (2020) Military programs and benefits. USA Gov.

- Military One Source (2018) 2018 Demographic Profile: Profile of the Military Community. Department of Defense.

- Lester P, Aralis H, Sinclair M, Kiff C, Lee K, et al. (2016) The impact of deployment on parental, family and child adjustment in military families. Child Psychiatry & Human Development 47(6): 938-949.

- Belsky J, Fearon RMP (2002) Early attachment security, subsequent maternal sensitivity, and later child development: does continuity in development depend upon continuity of caregiving? Attach Hum Dev 4(3): 361-387.

- Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ (2011) On the home front: Stress for recently deployed army couples. Family Process 50(2): 235-247.

- Gould M, Adler A, Zamorski M, Castro C, Hanily N, et al. (2010) Do stigma and other perceived barriers to mental health care differ across Armed Forces? J R Soc Med 103(4): 148-156.

- Department of Defense (2018) Department of defense announces fiscal year 2018 recruiting and retention numbers -- end of year report.

- Duttweiler R (2020) Here's what you need to know about reintegration.

- Brooks M, Graham Kevan N, Robinson S, Lowe M (2019) Trauma characteristics and posttraumatic growth: The mediating role of avoidance coping, intrusive thoughts, and social support. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 11(2): 232-238.

- Gross J (2002) Emotion regulation: affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology 39(3): 281-291.

- Romero DH, Riggs SA, Raiche E, McGuffin J, Captari LE (2020) Attachment, coping, and psychological symptoms among military veterans and active-duty personnel. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 33(3): 326-341.

- Ganz A, Yamaguchi C, Parekh B, Koritzky G, Berger SE (2021) Military culture and its impact on mental health and stigma. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship 13(4): 10.

- Gonzalez K, Berger S, Lopez B (2023) Women veterans reintegrating into civilian life. American Journal of Biomedical Science and Research 19(4): 507-518.

- Bohse W, Berger SE, MacMillin M (2022) Identification with military culture, drinking, and mental health stigma among Army Soldiers and Veterans. Novel Research in Sciences 11(2): NRS.000756.

- Yamaguchi C, Berger SE, Parekh B (2019) Military culture, substance use as a coping mechanism and fear of military personnel of obtaining treatment. Open Access: Journal of Addiction and Psychology 2(4): 1-9.

- Carver CS (1997) Brief cope inventory. Psyc TESTS Dataset.

- Marek LI, Moore LE (2015) Coming home: The experiences and implication of reintegration for military families. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health 1(2): 21-31.

- FOCUS Project (2017) FOCUS Project.

© 2024 Tyan Carrico. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)