- Submissions

Full Text

Novel Research in Sciences

Identification with Military Culture, Drinking, and Mental Health Stigma among Army Soldiers and Veterans

Wassaporn Bohse MA*, Stephen E Berger and Mark MacMillin

Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA

*Corresponding author: Wassaporn Bohse MA, Chicago School of Professional Psychology, USA

Submission: April 27, 2022;Published: May 27, 2022

.jpg)

Volume11 Issue2mAY, 2022

Abstract

Military values including honor, loyalty (commitment), courage, duty, respect, personal integrity, and selfless service make the US military one of the most prolific forces in modern day history. The codes of conduct and military values are indeed crucial parts for survival in theaters of war. However, the same values may generate stigma towards mental health treatment and present barriers to help-seeking behavior. This study examined the level of identification with military culture and its relationship to attitudes toward mental illness, mental health related help seeking behaviors and alcohol use. The study investigated differences among three sample groups, including active duty Army soldiers, Army veterans, and Civilian. The Identification with military culture was measured using the Ganz Scale (GIMC) [1]. Attitudes towards mental illness were measured using the Attribution Questionnaire-27 (AQ-27) and the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale-Short Form (SSMIS-SF). The analysis was conducted on the data collected on 54 active duty Army soldiers and Veteran participants and 51 general population participants who served as a contrast sample group.

Findings revealed differences between the active duty Army soldiers and Veterans versus general population on the GIMC, AQ-27, and SSMIS-SF. Specifically, active duty Army personnel and Army veterans scored higher overall on Total GIMC. Furthermore, active duty Army soldiers and veterans scored higher on the stigma attitudes of Blame, Help, and the Agree subscale of the SSMIS-SF, while the non-military general population had higher endorsement of stigma attitudes of Pity and Fear. Additional findings demonstrated individual differences within the active duty military personnel on the level of GIMC endorsement, AQ-27 (Help and Coercion), and SSMIS-SF (Self Stigma subscale). Differences were also found for time in service. These findings demonstrate the level of identification with military culture may be associated with stigma toward mental illness and mental health treatment among active duty Army soldiers and veterans. Additionally, level of identification with military culture may be a risk factor for alcohol abuse, depending on the level of cultural identification. Suggestions were provided for clinicians working with active duty and veteran personnel as well as for the military command.

Keywords: Keywords: Stigma; Military service; Help-seeking; Military culture; Mental health treatment

Introduction

The United States has a powerful military. As of 2021, the U.S. has the biggest budget for military operation of any country, with over two million active duty personnel [2]. The largest U.S. military service branch is the United States Army with 481,254 active duty soldiers stationed throughout the U.S. and on missions overseas. Every recruit needs to go through several processes including the Basic Combat Training (BCT) or the Boot Camp [3]. The basic training is a 10-week-long intense training that is designed to challenge one’s physical and mental strength. During this process, the recruits begin to acclimate and identify with the military culture, values, and a sense of comradery. Over the course of training and once stationed in a unit, soldiers learn that strength, both physical and mental is a desirable characteristic and weakness or injuries in either aspect is not only unacceptable but perceived as a liability for the unit and their own peers [4]. All of this is geared to instilling a “military culture” in the trainees.

Thus, Military Culture and lifestyle are ingrained in service members from the very start of their career. For all the U.S. military branches, eight core values (the “military culture”) are generally acknowledged [5]. A scale has been developed to capture these components of the military culture. The Ganz Scale of Identification with Military Culture (GIMC) was developed by Alexis Ganz (1) reflecting these eight core components of the Military Culture, specified as: (1) Believe in and devote yourself to something or someone: allegiance to others, (2) Fulfill obligation to the military, mission, and unit, (3) Trust that all people have done their jobs and fulfilled their duty, putting forth their best effort, (4) Put the welfare and needs of the nation, the military, and your peers and subordinates before your own, (5) Live by the military moral code and value system in everything you do, (6) Do what is right, legally and morally, (7) Face fear, adversity, and danger, with both physical and moral courage, and (8) Exhibit the highest degree of moral character, technical, excellence, quality and competence in what one has been trained to do.

Ganz’s study revealed significant relationships between GIMC endorsement and mental health seeking behaviors. She found that lower scores on personal courage as well as high overall identification with military culture were reflected in acceptance and help seeking for mental health issues [1]. These findings suggest that since soldiers associate mental health help seeking with a lack of courage, they are more likely to utilize other resources to cope with psychological pain in order to be able to maintain their military core value of courage-externally and internally. However, high endorsement of the Military Culture was associated with higher acceptance of seeking help for mental health issues suggesting that the over riding issue was making oneself fit for duty.

Serving in the military is considered the most stressful of all jobs (Statistica, 2018) with a job stress score of 72.47 (based on a 0-100 scale score). The second, third, and fourth most stressful jobs were firefighter (stress score 72.43), airline pilot (stress score 61.07), and police officer (stress score 51.97) respectively [5]. The constant separation from family and loved ones due to duty assignments, deployments, and training, along with the hostile or hazardous work environment significantly contribute to chronic stress. The demanding nature of the job means soldiers require effective medical and psychological services to accommodate the high level of stress.

Although soldiers are taught and molded to believe that physical pain and hardships are inevitable, especially in time of war, apparently, psychological pain is a subject that should not be brought up [6]. Speaking of psychological problems or seeking help is strongly discouraged among soldiers as it does not only portray weakness, but it can result in adverse actions such as loss of military clearance, inability to operate firearms, and even an administrative separation [7]. Therefore, most soldiers accept that they should not discuss their emotional discomfort or seek mental health services, but instead, they resort to maladaptive coping such as alcohol abuse, which is viewed as a much more acceptable behavior among service members [8].

Mental health stigma among soldiers has been discussed by many researchers [9-12]. According to the Deployment Health Clinical Center statistics, the U.S. Army has the highest mental health case prevalence among all U.S. military services. Out of all the mental health cases being treated, alcohol-related disorders account for one of the highest percentages of mental health diagnoses [13]. However, this statistic tends to only reflect the number of cases that have been documented in the military healthcare system and may not account for cases of alcohol abuse and co-occurring mental illnesses that have not been reported or gone untreated.

A recent study regarding stigma as a barrier to initiating and continuing mental health treatment in the U.S. Army population indicates that 82.4% of soldiers chose not to initiate treatment and 69.5% discontinued treatment due to the lack of perceived need and attitudinal reasons such as stigma-related concerns and negative attitudes toward mental health professionals [14]. In addition, a meta-analysis study of stigma as a barrier to help-seeking behavior in the military, suggests that over 60% of service members decide not to seek treatment, which is seen by them as weak and against their military values and is viewed as detrimental to their own pride and career [11].

Over the duration of their service contract, soldiers are required to always be prepared for field exercises, annual trainings, and deployment. They also undergo military inspections and other forms of assessment for combat readiness on a regular basis [15]. However, the outcomes of these exercises, trainings, and inspections also determine whether one would advance in their career or risk an administrative separation based on their poor performance or lack of competency [16]. Despite the federal right to privacy of medical and psychological health records under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996, the chain of command can “informally” question soldiers about their health issues as it is considered a matter of “welfare check.” The unit health and welfare inspection or “welfare check” is a military inspection in accordance with Military Rules of Evidence 313, in which a command can direct inspection of all parts of the organization including military personnel to determine and ensure the security, military readiness, good order, and discipline of the unit [17].

Since the launching of the War on Terror and the Global War on Terrorism after the September 11 attacks against the United States, many soldiers have been assigned to combat in a number of operations across the globe, namely Operation Enduring Freedoms (OEFs), Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), Operation Inherent Resolve (ISIL), Operation Active Endeavour (OAE), and the most recent, Operation Freedom’s Sentinel (OFS). The U.S. military involvement in these wars has resulted in an increase of mental diagnoses ranging from traumatic brain injury (TBI), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and substance-related disorders. The increase in mental illnesses among service members manifests in the alarming rate of suicide as more than 580 service members committed suicide, which is a 16 percent increase from 2019 TO 2020 [18].

An associated problem is that alcohol abuse is a widespread issue among soldiers. The excessive use of alcohol, especially upon return from deployment, is considered normal and acceptable among service members [19]. Heavy alcohol consumption is typically associated with the military culture. Alcohol is almost always incorporated into important military ceremonies such as military balls, promotion/retirement parties, as well as the military branch birthdays [20]. Although social and recreational drinking may not be harmful, many soldiers use alcohol as a tool to cope with stress and psychological pain they need to suppress and conceal from their comrades. Several studies suggest that military careerrelated stress, despite the location of assignment, induces bingedrinking behavior in service members [21,22].

In addition, the “suck it up” attitude planted among services members influences maladaptive coping such as alcohol and drugs use. This masculine outlook also reinforces the inhibition of emotional expression, which further deters soldiers from using mental health resources. Constant subtle or overt dissuasion from seeking mental health attention by the chain of command sends the message that emotional difficulties will be neglected and that other acceptable alternative coping mechanisms such as alcohol use is the only option [21].

Statement of the problem

“It is an odd paradox that a society, which can now speak openly and unabashedly about topics that were once unspeakable, still remain largely silent when it comes to mental illness” [23]. This quote from an author and mental illness de-stigmatization advocate perfectly summarizes the common attitude on mental illness. Stigma makes people feel damaged or abnormal, because a diagnosis of mental illness often leads to negative consequence and outlook from society. In the military, stigma regarding mental illness and treatment may extend to career concerns, confidentiality, and identity [24]. Therefore, to cope with mental illness without seeking official help, many service members resort to alcohol. The relationship between the U.S. Military and alcohol dates since the birth of the U.S. military [25]. Alcohol has been an acceptable tool for soldiers to cope with the intense stress of a combat environment, as well as to help ease the transitioning between the heightened experience of deployment to the relatively safe stateside assignment [26]. Alcohol abuse is a persistent problem in the military. Although prescription medications are given for physical injuries, whether acquired via combat or non-duty related, alcohol is typically chosen over psychotropic medications or psychotherapy to deal with emotional difficulty and psychological discomfort [20-27]. While the U.S. Army has a “zero tolerance policy” for substance use, first-time non-violent alcohol-related incidents, and driving under the influence, typically result in a “counseling statement” by the chain of command and mandatory alcohol dependency treatment, known as the Army Substance Abuse Program (ASAP). Soldiers are given a choice whether or not to seek mental health treatment for their personal issues. Hence, if soldiers choose to seek and receive treatment to address their psychological issues, mental health stigma follows [28].

The Military Culture places a high value on the physical readiness and emotional strength that are vital to mission accomplishment. These values imbed guilt and shame if mental health treatment is warranted [10-12]. Furthermore, the Military Culture places its value on the needs of the organization over one’s own needs, which implicitly discourages service members from discussing their personal problems and causes them to minimize their own needs [11,12]. According to the 2011 Department of Defense (DoD) Survey of Health Related Behaviors among Active Duty Military Personnel, 10.8% of current drinkers used alcohol as a way to disregard their personal problems, 13.8% consumed alcohol to deal with mood disturbance, and almost 9% drank to show a sign of camaraderie. In addition, several studies have found a correlation between stress, consumption of alcohol and emotional difficulties (Bray, Fairbank, & Marsden, 1999). With a large number of soldiers being deployed, physical and psychological injuries also become prevalent. With the stigma in the military associated with help seeking behavior, soldiers resort to a quick and easy remedy, alcohol, to deal with their emotional struggles and to suppress the acknowledgement of any presenting psychological problems they have.

Despite having numerous studies regarding alcohol and substance abuse in the military, there is a scarcity of research that aims to understand the relationship between the Military Culture and mental health help-seeking behavior among service members [29]. Specifically, the Military Culture is recognized as embracing 8 distinct but related components as delineated earlier and as specified in the GANZ scale. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between the Military Culture and each of its components with problematic utilization of alcohol and mental illness among U.S. Army soldiers and veterans.

The present study

Prior studies on alcohol and substance abuse among military personnel placed much emphasis on substance and alcohol use trends rather than the etiology of the problem. The present study seeks to clarify the relationships among mental health stigma, military culture identification, and alcohol use problems. The study investigated whether service members’ and veterans’ identification with the military culture are related to alcohol use as a coping tool. The focused population were active-duty Army soldiers and veterans who have completed Basic Combat Training (BCT) and served for at least one year treatment.

Methods

Participants

Samples of active-duty Army soldiers, veterans, and the general population were recruited. The participation recruitment was done via a public Facebook post to minimize the potential for undue influence. The participation was voluntary and individuals who opted to participate would click the link the link provided in the Facebook post to be directed to the screening page. The following individuals were excluded from this study: (1) individuals who have served or are currently serving in other branches of the U.S military (Airforce, Marine corps, and Navy) (2) individuals who are under 18 years of age (3) dependent adults or wards of the state (4) Prisoners.

Participants who met the inclusion criteria, were directed to the Informed Consent page. Once the participant agreed to the informed consent, they were directed to the research portion, which consists of a series of questionnaires. The questionnaires required approximately 30 minutes to complete. Once all the questionnaires were completed, participants were directed to the debriefing page. After reading the debriefing statement, the participant was provided an option to submit the data or withdraw from participation. Information from individuals who chose to withdraw from participation were not collected. In addition, participants were asked to recruit more persons for the research by passing on the Recruitment message

This study included active-duty soldiers and veterans who had or had not sought professional mental health treatment (from US military or from civilian mental health professionals) whether or not they had been diagnosed with a mental illness, as well as those who have an alcohol use problem. The only restriction on the general population sample group was that they must not have served in the United States Armed Forces or national guard and must be at least 18 years old. Only complete batteries were considered for this study. A complete battery consisted of a Demographic Questionnaire, Ganz Scale of Identification with Military Culture (GIMC), the Attribution Questionnaire-27 (AQ-27), and the Self-Stigma of Mental Illness Scale-Short Form (SSMIS-SF).

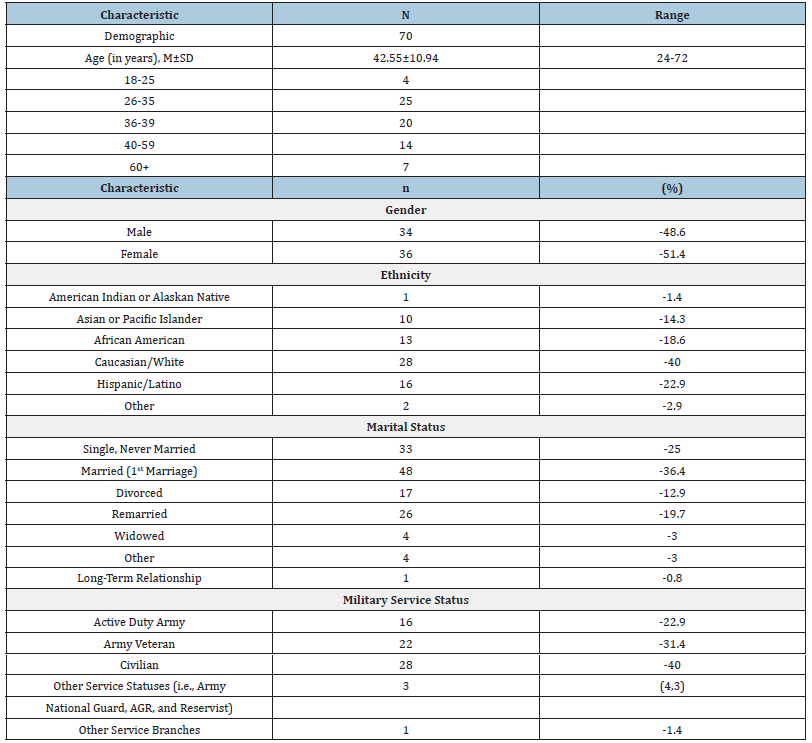

The final sample was 70 participants. There were 16 active-duty Army soldiers who completed all batteries. The Army veterans final sample included 22 participants. There were three participants who identified as other service status and one participant identified as active-duty, other branches. The “Civilian” group was 28 participants who completed all portions of the survey. See (Table 1) for further demographic information.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of participants.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire:. The demographic questionnaire asked for military service status, rank (if applicable), age, marital status, number of dependents, occupational status, and gender. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they had received previous treatment for mental health concerns, believed they needed treatment but had not sought treatment, or do not need treatment and had not sought treatment. Participants who stated that they had received mental health treatment were asked to indicate where they had received such treatment (e.g., military mental health professional or from a civilian mental health professional). All the sensitive personal information from the Qualtrics survey were deidentified to protect confidentiality of the participants.

The attribution questionnaire-27: (AQ-27) [30]. The AQ-27 is a 27-item questionnaire examining attitudes and externalized stigma toward individuals with mental illness. Each statement has a 9-point Likert scale answer choice labeled from “not at all” to “very much,” representing the respondents’ agreement with the attitude toward an individual with mental illness. The AQ-27 provides a brief vignette identifying an individual with mental illness. Once respondent had read the vignette, they were asked to provide answers on a Likert scale. The AQ-27 has been widely used in other studies to identify stigma [31-33]. The AQ-27 was used in a 2018 clinical research project by Alexis Ganz, with permission from the original author of the AQ-27, the scale was then adapted for the military population, to include: a vignette that is more representative of mental illness within the military and items that correspond with military cultural attitudes and core values. The senior researcher also obtained permission from the original author and Ganz to use the adapted version of AQ-27 in this study.

.The AQ-27 uses a Score Sheet, which identifies the individual questions that load onto each of the nine factors [31]. The more factors endorsed by the respondant (indicating negative attitude and stigma toward mental health), the higher the score. Validity and reliability of the AQ-27 were psychometrically validated by Brown, and it was found to exhibit an overall good reliability and validity. It was also found to have good convergent validity when compared with other measures of stigma [34]. The psychometric analysis conducted by Brown revealed that six out of the nine factors on the AQ-27 accounted for 65.29% of the variance. Internal consistency for the six factors ranged from fair to good. The six factors and their internal consistencies are: fear/dangerousness (α=93), help/ interact (α=82), responsibility (α=60), forcing treatment (α=79), empathy (α=77), and negative emotions (α=81).

Self-stigma of mental illness scale-short form: (SSMIS-SF) [30]. The SSMIS-SF measures one’s internalized self-stigma if they have a mental health condition. The instrument consists of 20 items to which respondents had to rate their level of agreement based upon a 9-point Likert scale from “I strongly disagree” to “I strongly agree.” The SSMIS-SF is scored using the SSMIS-SF Score Sheet, which loads questions onto the four subscales: Awareness, Agreement, Application, and Harm to Self-esteem. Higher scores indicate negative attitudes and stigma toward mental health.

A psychometric analysis on the SSMIS-SF denotes that it is psychometrically comparable to the original SSMIS. Corrigan et al. concluded that internal consistency ranged from fair (α=65) to good (α=87) across the four subscales [35]. Awareness and Agreement correspond with how the individuals apply the stereotypes to themselves-if the individual has a mental illness. Harm is whether the application of the stereotype is inducing/increasing harmful behavior, such as decreased help-seeking efforts, increased psychological symptoms, and alteration in self-perception (namely, lowered self-esteem). The Validity of the short form subscales were found to be sufficiently supported. For example, Harm on the SSMISSF was found to be inversely and significantly related to self-esteem across the multiple samples, various mental health diagnoses, and across two languages [35].

Ganz Scale of Identification with Military Culture (GIMC): The GIMC was developed by Alexis Ganz [1]. in an attempt to measure the extent to which one personally identifies with the US Military Culture, through their endorsement of the various components delineated in existing literature (www.army.mil/ values; www.navy.mil). The GIMC comprises eight statements that address eight core values from the different branches of the armed forces. Participants are asked to specify their level of agreement to each statement, and how each core value impacts their view or belief regarding mental health, on a 5-point Likert scale from “Not at All” to “Very Much.”

The GIMC was originally used in a 2018 study by Ganz. Since this instrument has not been widely utilized, the reliability and validity are yet to be established. However, the GIMC was also given to general population participants in a few studies in an attempt to develop a validity indicator as it could be hypothesized that individuals who have been in the military would exhibit a higher mean score than individuals who have never served in the military [1-29]. The previous studies found a significant difference between active-duty military personnel and the general population, with the active duty samples scoring significantly higher than the general population, thus supporting the validity of this measure.

Procedures

The participants who met the inclusion criteria, and who accessed the survey page indicated their willingness to participate by clicking “yes” to the Informed Consent cue. Participants further acknowledged their consent via the completion of the Qualtrics survey. Once they agreed to participate, respondents completed the demographic questionnaire, GIMC, AQ-27, and SSMIS-SF, in that order. The last page of the online Qualtrics survey contained a Debriefing Statement which included general information about the study and information regarding mental health resources should the participant desire mental health service if they were so. All the information gathered from the participants were deidentified and remained anonymously. All collected information and data were kept on a password protected computer to which only the senior researcher and the second author have access .

Result

Statistical analysis of the variables was conducted utilizing the IBM SPSS software package Version 27. Responses from 70 participants who completed all portions of the survey were included in data analysis. The military status is a categorical variable and participants were categorized into five groups according to their responses in the Demographic Questionnaire: Active-Duty Army, Army Veteran, Civilian, Other Service Statuses, and Active-Duty other Branches, but only responses from Active-Duty Army, Army Veterans, and Civilian sample groups were included in data analysis.

Significant effects and interactions of military service status, alcohol consumption, perception that drinking is a part of the military culture, mental health treatment history on Identification with Military culture (GIMC)

One-way ANOVAs were performed to determine whether there are significant effects of categorical variables of participant’s endorsement of the Identification with the Military Culture (GIMC). The results revealed significant relationships of military service status, alcohol consumption, perception that drinking is a part of the military culture, and mental health treatment sought.

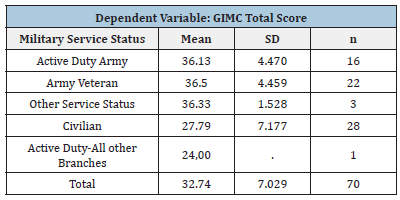

Military service status and identification with the military culture: There was a significant effect of Military Service Status on Identification with the Military Culture as measured by the GIMC (F(4,65) = 9.974, p = 001). The Active-duty Army Soldiers and Army Veterans scored equally high on the GIMC, whereas Civilians scored lower than the military sample groups. Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 2).

Table 2: Means and standard deviations for military and civilian participants on the GIMC.

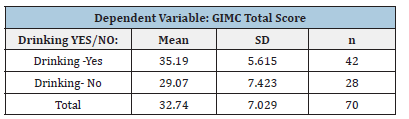

Drinking and GIMC: A significant effect of drinking on the identification with the military culture (GIMC) was found (F (1, 68) = 17.866, p = 001). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 3). Individuals who alcohol scored higher than those who do not on the GIMC.

Table 3: Means and standard deviations for drinkers and non-drinkers on the GIMC.

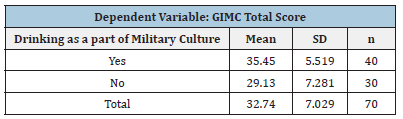

Perception that drinking is a part of the military culture and the GIMC: A significant effect of one’s perception that drinking is a part of the military culture on identification with the military culture (GIMC) was found (F (1, 68) = 15.385, p = 001). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 4). Individuals who perceive that drinking is a part of the military culture scored higher than those who do not on the GIMC.

Table 4: Means and Standard Deviations for Participants who think Drinking is a part of the Military Culture and those who do not on the GIMC.

Mental health treatment sought and identification with the military culture:There was a significant effect of mental health treatment sought and identification with the military culture (GIMC) (F(2, 67) = 13.797, p = 001). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 5). Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) analyses indicated participants who have sought treatment for mental health issues scored the highest and scored higher than those who chose not to answer (p= 023), as did those who have not sought treatment (p= 001).

Table 5: sought and those who have not on the GIMC.

The Effect of Military Variables on Stigma toward Mental Illness (AQ-27) Subscales Military Service Status on Stigma toward Mental Illness

Deployment status on stigma toward mental illness: When One-way ANOVAs were performed using deployment status, significant effects were found across all AQ-27 Subscales.

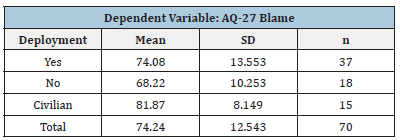

Blame: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ- 27 Blame Subscale (F (2, 67) = 5.477, p = 0.006). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 6). Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons denoted mean AQ-27 Blame score was significantly different between soldiers who have not been deployed and civilian participants (p= 004).

Table 6: means and standard deviations for participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 blame.

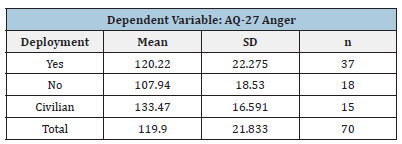

Anger: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ- 27 Anger Subscale (F (2, 67) = 6.489, p = 0.003). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 7). Tukey’s test denoted mean AQ-27 Anger score was lower for soldiers who have not been deployed and the civilian participants (p= 002).

Table 7: Means and Standard Deviations for Participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 Anger.

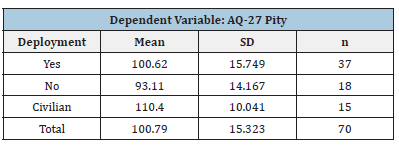

Pity: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ-27 Pity Subscale (F (2, 67) = 5.963, p = 0.004). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 8). Tukey’s test denoted the mean AQ-27 Pity score was significantly lower for soldiers who have not been deployed and civilian participants (p= 003).

Table 8:Means and standard deviations for participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 Pity.

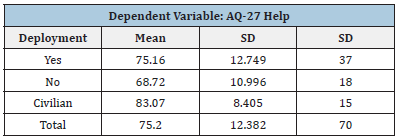

Help: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ-27 Help Subscale (F (2, 67) = 6.340, p = .004). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 9). Tukey’s test denoted themean AQ-27 Help score was significantly lower for soldiers who have not been deployed compared to the civilian participants (p= 0.002).

Table 9: Means and Standard Deviations for Participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 Help.

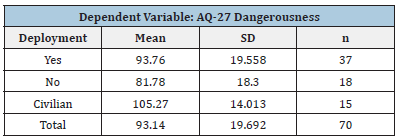

Dangerousness: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ-27 Dangerousness Subscale (F (2, 67) = 6.853, p = .002). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 10). Table Tukey’s HSD test denoted mean AQ-27 Dangerousness score was significantly lower for soldiers who have not been deployed and civilian participants (p= 001).

Table 10: Means and standard deviations for participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 dangerousness.

Fear: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ-27 Fear Subscale (F (2, 67) = 6.519, p = 002). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 11). Tukey’s test denoted the mean AQ-27 Fear score was significantly lower for soldiers who have not been deployed and civilian participants (p= 002).

Table 11: Means and standard deviations for participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 fear.

Avoidance: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ-27 Avoidance Subscale (F (2, 67) = 6.209, p = 003). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table12). Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons denoted mean AQ-27 Blame score was significantly lower forsoldiers who have not been deployed and civilian participants (p= 002).

Table 12: Means and standard deviations for participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 avoidance.

Segregation: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ-27 Segregation Subscale (F (2, 67) = 7.501, p = 001). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 13). Tukey’s test denoted mean AQ-27 Segregation score was significantly lower for soldiers who have not been deployed and civilians (p= <001).

Table 13: Means and standard deviations for participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 segregation.

Coercion: There was a significant effect of deployment on AQ- 27 Coercion Subscale (F (2, 67) = 7.530, p = 001). The mean and standard deviations are presented in (Table 14). Tukey’s HSD test for multiple comparisons denoted the mean AQ-27 Coercion score was significantly lower for soldiers who have not been deployed and civilian participants (p= <001). In summary, the results showed that civilian participants scored highest on all nine subscales. Soldiers who have not been deployed scored lowest, exhibiting the least stigma toward others with mental illness. However, soldiers who have deployed scored in the middle, suggesting that one effect of being deployed is to increase stigma regarding mental illness.

Table 14: Means and standard deviations for participants who have deployed, not deployed, and civilian on the AQ- 27 coercion.

The Effects of mental health treatment seeking history on stigma toward mental illness (AQ-27) subscales

Blame Subscale: A One-way ANOVA revealed that there was a statistically significant difference in AQ-27 Blame score across the three groups of participants based on whether they had sought mental health treatment. (F (2, 67) = 4.038, p = 022). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 15). Tukey’s test found that mean AQ-27 Blame score was significantly lower for participants who have sought mental health treatment and those who preferred not to answer (p= 026). (Table15) shows that participants who preferred not to answer scored significantly higher than those who have never sought mental health treatment.

Table 15: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment and those who have not on the AQ-27 blame subscale.

Anger subscale: A significant effect of mental health treatment sought on AQ-27 Anger score was found (F(2, 67) = 4.124, p = 020). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 16). It can be seen in Table 16 that participants who have sought mental health treatment scored lowest on this subscale and those who preferred not to answer scored highest (p=032).

Table 16: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment and Individuals who have not on AQ-27 anger subscale.

Help subscale: A One-way ANOVA noted a significant effect of mental health treatment sought on AQ-27 Help Score (F(2, 67) = 3.300, p = 0.043). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 17) Participants who have sought mental health treatment scored higher than those who preferred not to answer on the Help Subscale.

Table 17: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment and those who have not on the AQ-27 Help.

Dangerousness subscale: There was a significant effect of mental health treatment sought on one’s stigma toward mental illness on the AQ-27 Dangerousness score (F(2, 67) = 5.254, p =008). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 18). Tukey’s test revealed that mean AQ-27 Dangerousness score was significantly higher for those who preferred not to answer (p=021) than those who those have sought treatment as well as those who have not sought treatment (p=021).

Table 18: Means and Standard Deviations for Participants who have sought Mental Health Treatment and those who have not on the AQ-27 dangerousness

Fear subscale: There was a significant effect of mental health treatment history on one’s stigma toward mental illness on AQ-27 Fear (F(2, 67) = 4.153, p = 020). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 19). Tukey’s test revealed that mean Fear scores of participants who have sought mental health treatment was significantly lower than those who preferred not to answer (p= 036).

Table 19: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment and those who have not on the AQ-27 fear.

Segregation subscale: A One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of mental health treatment sought on Segregation (F (2, 67) = 5.513, p = 006). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 20). Tukey’s test revealed that participants who preferred not to answer scored higher than those who had sought treatment (p=016) and higher than those who had not sought treatment (p=.019).

Table 20: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment and those who have not on the AQ-27 segregation.

Coercion subscale: A One-way ANOVA was performed to compare the effect of Mental Health Treatment sought on AQ-27 Coercion Subscale. The results revealed that there was a statistically significant difference in AQ-27 Coercion score across the three groups of participants (F(2, 67) = 4.110, p = 021). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 21).Tukey’s test found that mean AQ-27 Coercion score was significantly lower for participants who have sought mental health treatment compared to those who preferred not to answer (p= 031).

Table 21: Means and Standard Deviations for Participants who have sought Mental Health Treatment and those who have not on the AQ-27 Coercion.

The effects of mental health treatment sought for nonservice connected condition on stigma toward mental illness (AQ-27) subscales

Data analysis also revealed significant effects of mental health treatment sought according to participant’s answer to the Demographic Question “Have you ever sought mental health treatment?” on six out of nine AQ-27 subscales, including Blame, Anger, Dangerousness, Fear, Segregation, and Coercion. No significant effects of mental health sought were found on Pity, Help, and Avoidance scores.

Blame subscale: There was a significant effect on self-stigma of Blame of mental health treatment sought for a non-service connected condition (F(2, 67) = 3.372, p = 040). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 22). Tukey’s test denoted the mean AQ-27 Blame score was significantly lower for those who have not sought mental health treatment for a Non- Service Connected Condition compared to those who preferred not to answer (p= 031).

Table 22: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment for non-serviceconnected condition and those who have not on the AQ-27 blame subscale.

Anger Subscale: There was a significant effect of mental health treatment sought for non-service connected condition on the AQ27 Anger score (F(2, 67) = 3.400, p = 039). The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 23. The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 23).Tukey’s test denoted mean AQ-27 Anger score was significantly lower for who have not sought mental health treatment for a Non-Service Connected Condition compared to those who preferred not to answer (p= 030).

Table 23: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment for non-serviceconnected condition and those who have not on the AQ-27 anger subscale.

Dangerousness subscale: There was a significant effect of mental health treatment sought for non- service connected condition on the AQ27 Anger score (F(2, 67) = 4.604, p = 013). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 24). Tukey’s test denoted mean value of AQ-27 Dangerousness score was significantly different between Participants who have not sought mental health treatment for Non-Service Connected Condition and those who preferred not to answer (p= 010).

Table 24: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment for non-serviceconnected condition and those who have not on the AQ-27 dangerousness.

Fear subscale: A One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of mental health treatment sought for a non-service connected condition on the AQ-27 (Fear F(2, 67) = 4.302, p = 0.17). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 25). Turkey’s test denoted mean AQ-27 Fear score was significantly different between Participants who have not sought mental health treatment for Non-Service Connected Condition and those who preferred not to answer (p= 014).

Table 25: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment for non-serviceconnected condition and those who have not on the AQ-27 fear.

Segregation subscale: A One-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of mental health treatment sought for non-service-connected condition on the AQ-27 Segregation F (2, 67) = 4.500, p = 015. The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 26).Tukey’s HSD test denoted mean AQ-27 Segregation score was significantly lower for who have not sought mental health treatment for Non- Service-Connected Condition compared to those who preferred not to answer (p= 011).

Table 26: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment for non-serviceconnected condition and those who have not on the AQ-27 segregation.

Coercion subscale: There was a significant effect of mental health treatment sought for non-service connected condition on the AQ27 Coercion score AQ27 (F(2, 67) = 3.590, p = 033). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 27). Tukey’s test denoted mean AQ-27 Coercion score was significantly lower for those who have not sought mental health treatment for a Non-Service Connected Condition and those who preferred not to answer p= 025. However, SPSS data analysis did not show significant effects of other categorical factors, including gender, age, ethnicity, education, marital status, military status, time in service, deployment, and whether the participant had sought mental health treatment for service-connected condition on any of the AQ-27 subscale scores.

Table 27: Means and standard deviations for participants who have sought mental health treatment for non-serviceconnected condition and those who have not on the AQ-27 coercion.

The effects of demographic variables on self-stigma toward mental illness (SSMIS-SF)

Awareness index: Deployment yielded a significant effect on the SSMIS-SF Awareness score (F (2,67) = 4.619, p = 013). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 28). Tukey’s test revealed a significant difference between soldiers who have and have not been deployed (p= 012) as well as between soldiers who have deployed and civilians (p= 0276).

Table 28: Means and Standard Deviations for Highest Education achieved on the SSMIS-SF Awareness.

Application index: One-way ANOVAs showed that deployment was also the only factor that bore significant effect on the SSMISSF Application score (F (2,67) = 3.504, p = 036). The means and standard deviations are presented in Table 29. Turkey test revealed a significant statistical difference between participants have not been deployed and civilians p= 040. The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 29).

Table 29: Means and standard deviations for deployment on the SSMIS-SF Application.

Harm to self-esteem index: One-way ANOVAs were performed for the following variables: service status, time in service, rank, deployment status, mental health treatment sought, need for mental health treatment for service-connected condition, need for mental health treatment for non-service-connected condition, distress from drinking, and referral for mental health treatment on all SSMIS-SF Indexes. The results showed that time in military service, deployment, mental health treatment sought (in general), need for mental health treatment for service-connected and nonservice connected condition, distress from drinking, and referral for mental health treatment were factors that bore significant effects on the SSMIS-SF Harm to Self-Esteem score.

Table 30: Means and standard deviations for time in service on SSMIS-SF harm to self-esteem.

Time in military service had a significant effect on Harm to Self-Esteem (F(4,65) = 3.451, p = 013). Tukey’s test revealed a significant difference between civilians and participants who were retired from military service and have not been deployed (p= 041). A significant effect was also found between those who have been in service for 10-15 years and those who were retired (p= 012). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 30).

A significant effect of deployment on Harm to Self-Esteem was found (F (2,67) = 16.054, p =001). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 31). Tukey’s test revealed a significant statistical difference between participants who have and have not been deployed (p= 007). Those who have been deployed also scored higher than civilians (p= 002). Additionally, a significant difference was also found between participants who have not been deployed and civilians (p= 001).

Table 31: Means and standard deviations for deployment on SSMIS-SF harm to self-esteem.

Mental health treatment sought had a significant effect on Harm to Self-Esteem (F (2,67) = 9.075, p <001). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 32). Tukey HSD Post-hoc test for multiple comparisons revealed a significant difference between participants have sought mental health treatment and those who preferred not to answer (p= <001). Need for mental health treatment for a service-connected condition yielded a significant effect on Harm to Self-Esteem (F (2,67) = 3.863, p = 026). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 33).Tukey’s test revealed a significant statistical difference between participants who do not need mental health treatment for service-connected condition and those who preferred not to answer (p= 032).

Table 32: Means and standard deviations for mental health treatment sought on SSMIS-SF harm to self-esteem.

Table 33: Means and standard deviations for need for mental health treatment for service- connected Condition on SSMIS-SF harm to self-esteem.

Table 34: Means and standard deviations for need for mental health treatment for non-service- connected condition on SSMIS-SF harm to self-esteem.

Table 35: Means and standard deviations for distress or impairment from drinking on SSMIS-SF harm to selfesteem.

Need for mental health treatment for a non-service-connected condition yielded a significant effect on Harm to Self-Esteem (F (2,67) = 6.586, p = 002). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 34). Tukey’s test revealed a significant statistical difference between participants who need mental health treatment for a non- service connected condition and those who reported it was not applicable (p= 042). A significant difference was also found between those who do not need mental health treatment for service- connected condition and civilians (p= 0.002). There was also a significant effect of distress or impairment from drinking on Harm to Self-Esteem (F (2,67) = 4.109, p = 021). The means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 35). Tukey’s test revealed a significant statistical difference between participants who did not endorse distress or functioning impairment from drinking and those who preferred not to answer (p= 015). Last, a significant effect of referral for mental health treatment on Harm to Self-Esteem was noted (F (2,67) = 4.250, p = 018). Means and standard deviations are presented in (Table 36). Tukey’s test revealed a significant statistical difference between participants who have not been referred to mental health treatment and those who preferred not to answer (p= 014).

Table 36: Means and standard deviations for referral for mental health treatment on SSMIS-SF harm to self-esteem.

The relationship of military service status and need for mental health treatment for a service-connected condition

A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between military service status and need for mental health treatment sought for a service-connected condition. A significant relationship was found between military service status and self-report of mental health treatment sought for a service connected condition (X2 (8)= 45.932, p=<001). As can be seen in (Table 37), army veterans were disproportunately likely to report needing treatment for a service connected condition.

Table 37:Need mental health treatment for service-connected condition by military service status.

The relationship between time in service and reported need for mental health treatment for a service-connected condition

The data analysis also found that time in service was also associated with reported need for mental health treatment for a service connected condition (X2 (8)= 36.781, p=<001). As can be seen in (Table 38), military participant who have been in service longer were more likely to report needing mental health treatment for a service connected condition with the exception of those who reported 16 or more years of serve and/or retired.

Table 38: Need mental health treatment for service-connected condition by time in military service.

The relationship between deployment and reported need for mental health treatment for a serviceconnected condition

In addition, deployment also played an important role whether the individual reported a need for mental health treatment for a service connected condition (X2 (4)=42.329, p=<001). As can be seen in (Table 39), military samples who have been deployed endorsed the need for mental health treatment for a service connected condition more than those who have not.

Table 39: Need for mental health treatment for service-connected condition by deployment status.

Discussion

Military values have existed since the United States Military emerged in the Revolutionary war, circa 1775. It is generally recognized that there is a “military culture” that is reflected in 8 values [1]. These values form part of what is thought of as the military culture that is necessary for survival in theaters of war. Yet, the way these values are applied in life by service personnel appear to present barriers to mental health care. This study was designed to examine the relationships among identification with the military culture, alcohol consumption, and mental health stigma. The relationship between stigma toward mental health problems among military personnel and veterans is well established [11]. Others have also explored whether this type of stigma is associated with how much one identifies with the military culture [1-36]. The current study also addressed whether alcohol use is a way to cope with and/or mask the underlying mental issues. Studies have concluded that mental health problems and suicides among service member could be systematic [37]. One of the two prominent factors in this military wide systematic issue are the military leadership and the military culture that creates overwhelming stress, contributory to mental health issues, and stigmatizes mental health treatment. According to Department of Defense statistics in 2020, the United States Army had the highest suicide rate at 36.4 deaths per 100,000 soldiers. Approximately 30 percent of military suicides in 2020 were active-duty soldiers. By the end of 2020, a total of 377 active duty service members committed suicide, which had increased from 348 deaths in 2021 [38]. In order to provide the most effective and appropriate treatment to service members and veterans who need mental health services, it is crucial to recognize stigmas surrounding mental illness and explore coping skills that are considered acceptable in the military culture. One of the most endorsed coping skills for service members is drinking, as it is considered acceptable in the military culture.

The findings from this study help clarify certain stigma and negative attitudes toward mental illness and treatment seeking by service personnel. It is essential to understand this in the development of an effective treatment approach and mental health resource distribution strategies to encourage service members and veterans to be open about mental illness and to seek treatment. Conceptually, the statistical analyses indicate that the level of identification with the military culture is affected by deployment and length of service. Those who have been in military service longer and those who have deployed, endorsed higher identification with the military values. Endorsement of the military culture also weighs one’s perception about mental illness and acceptability of drinking. Consistent with Ganz, those who identify or endorse the military culture tend to have stigma toward mental illness [1]. This stigma influences one’s ability to seek mental health treatment or accept the need for mental health treatment. The results also revealed that those who endorsed the military values were more likely to perceive drinking as acceptable (Tables 3 & 4). They are also more likely to develop a drinking problem if mental health problems are ignored and left untreated. Therefore, it is important for the military to destigmatize mental illness and change the approaches in providing mental health services. Furthermore, the military should provide psychoeducation about mental health to service members from all levels of the chain of command before the condition become fatal.

Identification with the military culture (GIMC)

The Ganz Scale of Identification with Military Culture (GIMC) measures degrees of identification with military cultural attributes from each branch of the United States Armed Forces [1]. The findings of this study indicate significant differences were evident on half of the military values identified by the GIMC. This finding was consistent with what Ganz had found previously [1]. Military participants, including active-duty soldiers, army veterans, and other service statuses, such as army national guard, active guard reserve (AGR), and reservists reported a high level of their identification with the military culture as reflected by their GIMC total scores. In addition, further examination of participants’ responses to each value on the GIMC revealed military samples scored much higher than the civilian sample on the following values: Fulfill obligations to the military, mission, and unit value, and: Put the welfare and needs of the nation, the military, peers and subordinates before one’s own, and: Live by the military moral code and value system in everything one does, as well as the value: Exhibit the highest degree of moral character, technical, excellence, quality, and competence as trained to do.

In contrast, there was no difference among sample groups regarding the value: Believe in and devote self to something or someone; allegiance to others, nor to the value: Trust that all people have done their jobs and fulfilled their duty, putting forth their best effort, nor to the value of: Do what is right, legally, and morally, nor to the value: Face fear, adversity, and danger with both physical and moral courage. Clearly, some of the values of the military culture are particularly based on military specific values, while other values reflect general societal values. That perspective is consistent with the theorizing of Ganz in explaining military culture vales on which she got difference between military personnel and civilians, and where she did not [1].

Mental health treatment seeking behavior was examined whether it has an impact on a participant’s identification with the military culture. Higher GIMC score was linked to participant’s lower tendency to seek mental health treatment. Only seven of the 70 participants indicated they have sought mental health treatment in the past. Interestingly, a large number of participants (n=19) preferred to not answer this question. Possibly, those participants may have sought mental health treatment but chose not to report it, even anonymously, as many participants viewed seeking mental health treatment negatively and so they do not report seeking help.

The findings also support the theory that identification with the military culture affected one’s drinking habits, as those who said they drink scored higher on the GIMC. Further examination revealed that more than half of the participants (n=42) reportedly drink. Additionally, this finding suggests drinking is acceptable in general in the military. Approximately 57% of participants considered drinking as a part of the military culture.

Stigma toward mental illness (AQ-27) subscales

Upon initial investigation, military status did not appear to influence one’s stigma toward mental illness. However, when examining deployment status on stigma toward mental illness (AQ- 27), deployment had significant effects across all of the subscales of stigma toward mental illness. Civilians scored highest on all AQ-27 subscales; soldiers who have deployed scored the second highest, and soldiers who have not been deployed scored the lowest. However, we can clearly see that the deployed scored higher than those who have not been deployed even though the differences did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance.

Self-stigma of mental illness scale-short form (SSMIS-SF)

The SSMIS-SF comprises a list of stereotypes representing selfstigma of mental illness across four subscales including: awareness, agreement, application, and harm to self [30-35]. Corrigan and colleagues suggest a model in which self-stigma of mental illness occurs in four phases, such that the person develops awareness about mental illness, agrees with the stereotype, internalizing the stereotype and then experiences harmful effects toward one’s selfesteem [35]. Awareness and agreement reflect how the individual recognizes the stereotypes exist, and how much they agree with such stereotypes. Application infers the internalization of the stereotype. Harm indicates a decrease in self-esteem and helpseeking behaviors.

Higher scores epitomize more agreement with, and internalization of the stereotypes. The results indicated deployment plays an important role in endorsement of the stereotypes. While civilians scored the highest on this Index, deployed soldiers scored the next highest. Deployment is recognized as one of the biggest milestones in one’s military career [39]. Soldiers who have been deployed endorsed higher awareness on the SSMIS-SF. This means soldiers who have deployed are more aware of common stereotypes about mental illness. This could be due to witnessing the feedback their fellow soldiers receive when they disclose mental health concerns. On the other hand, this could be a result of what has been termed “Post Traumatic Growth.” According to Chopik and colleagues, post-traumatic growth occurs after one has experienced a traumatic event, such as deployment. Soldiers’ personality, perception, and character strengths are developed as a result of deployment, and awareness is a part of one’s perception [40]. Therefore, the increased awareness of stereotypes could be a part of a soldier’s character that is shaped by the experience of deployment.

The Application subscale explores one’s belief that if they have mental illness, they will apply the stereotypes to themselves. When taking a closer look at the results, deployment and time in service both have significant impact on how a participant applies the stereotypes about mental illness to themselves. Soldiers who have been deployed scored higher than those who have not, an interestingly, they scored higher on AQ27 Blame subscale. Thus, those who have been deployed blame themselves-take responsibility if they have a mental illness. With civilians scoring highest, it could be speculated that, in general, civilians accept stereotypes uncritically, whereas military service, but not being deployed, can actually mitigate the stereotype.

The Harm to self-esteem Index score indicates one’s belief that they would respect themselves less if they have mental illness. The findings revealed deployment and time in service each had a significant effect on harm to self-esteem as a result of internalized stereotypes. While civilians scored highest on this Index also, the mean scores for soldiers who have been deployed were next highest. This means soldiers who have been deployed are more likely to have lower self-esteem due to having mental illness compared to soldiers who have not been deployed. The findings also showed that longer time served was also associated with higher scores on this Index.

Clinical implications

Clearly, sensitivity to a person’s identification with the military culture and the values acquired due to serving in the armed forces is critically important. The Department of Defense (DOD) employs more than 8,000 psychologists as of 2018 [41]. Soldiers’ or Veterans’ identification with the military values clearly affects their help seeking behavior. The ramification of untreated mental illness ranges from duty limitations, recommendation for separation from the service, to risk of suicide [42]. The understanding of correlations between identification with the military culture and mental health treatment seeking could change the way clinicians approach, conceptualize, and develop individualized treatment plans. For example, a clinician who treats military personnel may explain mental illness and presenting symptoms in a way that does not make the patient feel “labeled.” Normalizing mental health issues and providing psychoeducation to military leadership could also encourage soldiers and veterans to seek treatment when needed.

The study also found that deployment has significant impact to soldiers’ stigma or stereotypes about mental illness. Thus, clinicians should be especially alert to possible stereotypes and internalized stigma when working with soldiers or veterans, especially those who have been deployed. Blame (AQ-27) and Harm to Self-esteem (SSMIS-SF) were the most prevalent mental illness stigma found in this study. Furthermore, clinicians should be aware that drinking is a part of the military culture. Soldiers and veterans who internalize military values are likely to resort to drinking to cope with emotional distress and mental health symptoms rather than seek help from mental health professionals. Drinking affects a patient’s mental state and ability to participate in treatment. Apart from benefitting treating clinicians, the findings could also be useful to the military itself. Leadership needs to address and normalize the need for mental health treatment. For example, mental health awareness class or training should be incorporated into Basic Combat Training (BCT) or Boot Camp’s curriculum [3]. Rather than waiting for mental health issues to arise, destigmatizing mental illness while recruits are acculturating and assimilating with the military culture could foster help seeking behavior. Additionally, military leadership should be trained to recognize mental health symptoms and implement preventive care such as providing utilization of an open-door policy that allows soldiers to approach leadership about their emotional issues.

Limitations and Future Research

A limitation is that the GIMC has only been used in a few studies, thus norms and reliability have not been established. However, many of the findings with the scale are intuitively logical. Another potential limitation is that the sample size is too small making data analyses somewhat insensitive. Due to sampling technique using social media, the study may not reach prospective participants who have limitations of access, thus, technological challenges may have detered prospective participants from accessing and completing the survey. In addition, external validity cannot be determined as no independent behavioral observations were obtained. In addition, other factors such as differences in work setting, combat exposure, MOS related stress, and frequency in deployment rotations may also impact the findings. Regarding diversity considerations, most US Army service members and veterans are male and findings from female samples may be underrepresented due to this population structure.

Summary and Conclusion

This study investigated how one’s identification with the military culture may impact their perception about mental illness and whether such identification correlates with likelihood to drink alcohol as a coping mechanism for psychological distress. The results showed that the relationships among identification with the military culture and stigma toward mental illness and drinking habits indeed exist. Not surprisingly, the findings confirm prior findings that having served in the United States military is associated with higher endorsement of the military culture. In addition, deployment and time in service contribute to increased identification with the military culture. Higher endorsement of military values also associates with drinking, sort of a military cultural value in itself.

The results also reveal that military service, indeed, affects how one perceives mental illness. Deployment and length of service influence one’s negative outlook on mental illness, internalized stigmas, and mental health treatment. Specifically, assigning blame to individuals with mental illness and decreased self-esteem (if diagnosed with mental illness) are the more common stereotypic stigma toward mental illness of these service personnel. In addition, the results show that individuals who drink are less likely to seek mental health treatment. This suggests that drinking is viewed as a more acceptable approach to combat mental illness than seeking help from professionals. Thus, it is vital that US Military leadership recognize, acknowledge, and incorporate the findings to take a proactive approach in promoting help seeking among service members.

References

- Ganz A (2018) The Ganz scale of identification with military culture (GMIZ) is mental health stigma among active duty military a cultural problem? Orange CA: American School of Professional Psychology, USA.

- Duffi E (2021) Armed forces of the United States-Statistics & Facts.

- United States Army (2018) Basic combat training: The ten-week journey from civilian to soldier. Go Army.

- Hall LK (2011) The importance of understanding military culture. Social Work in Health Care 50(1): 4-18.

- Statistica (2019) Most stressful jobs in the United States in 2019.

- Mockenhaupt B (2012) A state of military mind. Pacific Standard Magazine, USA.

- Shay J (2005) The obstacles in getting help. Frontline: The Soldier's Heart.

- Genevieve A, Cunradi C (2007) Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, USA.

- Ben Zeev D, Corrigan PW, Britt TW, Langford L (2012) Stigma of mental illness and service use in the military. J Ment Health 21(3): 264-273.

- Hoge CW, Auchterloni JL, Milliken CS (2006) Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA 295(9): 1023-1032.

- Sharp ML, Fear NT, Rona RJ, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. (2015) stigma as a barrier to seeking health care among military personnel with mental health problems. Epidemiol Rev 37: 144-162.

- McFarling L, Angelo DM, Drain M, Gibbs DA, Olmsted KLR (2011) Stigma as a barrier to substance abuse and mental health treatment. Military Psychology 23(1): 1-5.

- The Deployment Health Clinical Center (2017) Mental health disorder prevalence among active duty service members in the military health system, fiscal years 2005-2016. Defense centers of excellence for psychological health and traumatic brain injury center. The Deployment Health Clinical Center. Washington, USA.

- Naifeh JA, Colpe L, Aliaga P, Sampson NA, Heeringa SG, et al. (2016) Barriers to initiating and continuing mental health treatment among soldiers in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Mil Med 181(9): 1021-1032.

- Chapman PL, Cabrera D, Valerla MC, Baker M, Elnitsky C, et al. (2012). Training, deployment preparation, and combat experiences of deployed health care personnel: Key Findings from deployed US army combat medics assigned to line units. Mil Med 177(3): 270-277.

- Taub F (2014) The essential guide to moving up the ranks of the US military. The Duffle Blog.

- US Army (2010) conducting unit health and welfare check. Fort Knox.

- Myers M (2021) Military suicides up 16 percent in 2020. Military Times.

- Campbell SL, Ursano R, Kessler R, Sun X, Heeringa S, et al. (2018) Prospective risk factors for post-deployment heavy drinking and alcohol or substance use disorder among US Army soldiers. Psychol Med 48(10): 1624-1633.

- Ames G, Cunradi C (2004-2005) Alcohol use and preventing alcohol-related problems among young adults in the military. Alcohol Research & Health 28(4): 252-257.

- Bray RM, Fairbank JA, Marsden ME (1999) Stress and substance use among military women and men. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 25(2): 239-56.

- Stahre MA, Brewer RD, Fonseca VP, Naimi TS (2009) Binge drinking among US active-duty military personnel. Am J Prev Med 36(3): 208-217.

- Bray G (2010) Medical therapy for obesity. Mount Sianai Jorunal of Medicine 77(5): 407-417.

- Sanchez BC (2021) Reducing the stigma and encouraging mental health care in the military. Airforce Medical Service.

- Associated Press (2018) Study says military drinking culture now a crisis.

- Jones E, Fear NT (2011) Alcohol use and misuse within the military: A review. International Review of Psychiatry 23(2): 166-172.

- Committee on prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and management of substance use disorders in the US armed forces; Board on the health of select populations; Institute of Medicine. In: O Brien CP, Oster M, Morden E (Eds.), (2013) Substance use disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); Understanding Substance Use Disorders in the Military.

- Young JL (2016) Military mental health: Understanding thecirsis. Psychology Today.

- Yamaguchi C, Berger SE, Parekh B (2019) Military culture, substance use as a coping mechanism and fear of military personnel of obtaining treatment. Open Access J Addict and Psychol 2(5): 1-9.

- Corrigan PW, Rafacz J, Rüsch N (2011) Examining a progressive model of self-stigma and its impact on people with serious mental illness. Psychiatry research 189(3): 339-343.

- Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N (2012) Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: A meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv 63(10): 963-973.

- Corrigan PW, Powell KJ, Fokuo JK, Kosyluk KA (2014) Does humor influence the stigma of mental illnesses? J Nerv Ment Dis 202(5): 397-401.

- Pinto MD, Hickman R, Logsdon MC, Burant C (2012) Psychometric evaluation of the revised attribution questionnaire (r-AQ) to measure mental illness stigma in adolescents. J Nurs Meas 20(1): 47-58.

- Brown M, Lettieri C (2008) State policymakers: Military families.

- Corrigan PW, Ben Zeev D, Brit TW, Langford L (2012) Stigma of mental illness and service use in the military. Journal of Mental Health 21(3): 264-273.

- Turchik J, McLean C, Rafie S, Hoyt T, Rosen C, et al. (2013) Perceived barriers to care and provider gender preferences among veteran men who have experienced military sexual trauma: A qualitative analysis. Psychol Serv 10(2): 213-222.

- Moradi Y, Dowran B, Sepandi M (2021) The global prevalence of depression, suicide ideation and attempts in the military forces: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of cross sectional studies. BMC Psychiatry 21(510).

- Orvis KA (2021) Department of Defense (DoD) Quarterly Suicide Report (QSR) 4th Quarter, CY 2020. Defense Suicide Prevention Office (DSPO), Washington DC, USA.

- Williams A (2019) The civ-mil divide: What’s a civilian like me doing in a veteran leadership program like this? A 2019 stand-to veteran leadership program scholar reflects on her participation in the program as a civilian. George W Bush Presidential Center.

- Chopik WJ, Kelley WL, Vie LL, Douglas G, Bonett DG, et al. (2020) Development of character strengths across the deployment cycle among US Army soldiers. J Pers 89(1): 23-34.

- Abrams Z (2019) Serving the armed forces. Monitor on Psychology 50(10): 58.

- Gillison DH, Kellerm A (2020) Devastated US mental health-healing must be a priority. National Alliance on Mental Illness. Opinion Contributors.

© 2022 Wassaporn Bohse MA. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)