- Submissions

Full Text

Forensic Science & Addiction Research

Drug Use Patterns in China: From Past to Present

Yunran Zhang and Hua Zhong*

Department of Sociology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, China

*Corresponding author: Hua Zhong, Department of Sociology, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, NT, China

Submission: December 19, 2017; Published: December 21, 2017

ISSN: 2578-0042 Volume1 Issue5

Abstract

In China, the past two decades have witnessed the rising popularity of synthetic drugs, which has profoundly changed the previous drug consumption structure that was dominated by heroin. Synthesizing the results reflected in official statistics and our empirical studies, this letter describes the drug use patterns in China from past to present. The increasing synthetic drug use in China is consistent with the global trend and new anti-drug policies in the world need to be developed to face such challenges.

Introduction

Recent years have witnessed a "substantial escalation" in the use of new psychoactive substances (NPS) across class, race, and gender in some developed countries such as UK and US BBC [1]. This phenomenon exists not only in developed countries but some developing countries like China. Today, China is one of the biggest synthetic drug manufacturing countries SCMP [2]. Due to the easy access to synthetic drugs, in 2014, the proportion of synthetic drug users reached 49.4%, firstly exceeding the proportion of opiates users (49.3%) in China China National Narcotics Control Commission [3]. Based on official data and existing studies, here we try to briefly describe the drug use patterns in China from past to present.

The History of Drug Use in China

China has a long history of drug (especially opium) use. According to some historical accounts, opium was first brought into China by Arab traders during the Tang dynasty (618-907) Li & Fang [4]. Opium was initially used for medicinal purposes and people ate the raw form of opium. Later on, more and more people inhaled the smoke form of opium and got addicted to opium Li & Fang [4]. In 1729, Emperor Yongzheng of the Qing dynasty imposed the first opium regulations, which banned the sale and distribution of opium Dikotter et al. [5], Liang et al. [6]. Subsequently, Qing government carried out a series of regulations to control the spread of opium. However, the outbreak of the Opium War in 1840 marked the failure of Qing"s series of opium control regulations and finally led to the fall of the Qing dynasty. The full criminalization of opium smoking occurred during the nationalist government period (1927-1937) Dikotter et al. [5]. The drug problems had not been eradicated in China because of the turbulent social situations (wars) during 1930s and the 1940s.

Such situations lasted until Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took power in 1949. In this year, the number of drug addicts were estimated to be 20 million Dupont [7]. After the founding of People's Republic of China, CCP launched national anti-drugs campaigns in which the general public were mobilized to identify drug users and those drug users eventually got harsh punishments. Meanwhile, mass education was also conducted to spread the harmful effects of drugs. The harsh actions almost made China become a drug free society in next few decades until the Opening up in the end of 1970s Liang et al. [8].

Heroin Dominated Era

Since the "open door" policy being carried out, large number of drugs especially heroin, has been trafficked to China mainly from two regions, Golden Triangle (in particular Myanmar) and Golden Crescent (including parts of Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan) China National Narcotics Control Commission [9]. The famous "China Routes" of drug trafficking include both the Golden Triangle- Yunnan-Guangdong route and the Golden Crescent-Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region route Tanner [10]. The Myanmar-Yunnan- Guangdong route is traditionally more preferred. Drugs from this route are either consumed directly in Southern China, or trafficked onward to interior provinces. Foreign-made heroin from Golden Triangle account for about 75% of all heroin seized by authorities in China Zhang [11]. The other foreign-made heroin are mainly from the Golden Crescent China Daily [12].

The escalating heroin smuggling industry encouraged the growth of domestic drug market in China. Consequently, the drug users also increased. However, before 1990, only limited laws or regulations stipulating the disposition for drug users, e.g., Regulations on the People's Republic of China on Administrative Penalties for Public Security [13] and Measures for the Control of Narcotic Drugs [14]. Moreover, these two statutes only stipulates the length of detention and the amount of fine but no rehabilitation for discovered drug users. Several years later, to strike the increasing drug smuggling industry, Standing Committee of the National People's Congress issued the Decision on the Prohibition against Narcotic Drugs [15]. The Decision stipulated much harsher punishments for drug smuggling and possession. Furthermore, the Decision listed more detailed disposition for discovered drug users. For example, they would be subjected to compulsory drug rehabilitation and re-education through labor.

However, it seemed that the harsh laws and regulations didn't achieve the expected deterrence goals. In 1990, there were 70,000 registered drug users in China and heroin users are the dominant group Zhao, et al. [16]. After 1990, this number continued increasing even more rapidly due to the rise of synthetic drugs.

The Rise of Synthetic Drugs

Compared to hard drug users, some synthetic drug users report that they are less physically addicted. Some typical kinds of synthetic drugs include methamphetamines, ketamine, LSD, ecstasy (MDMA), and so on. As these new types of drugs are usually used in parties, discos, and clubs, they are also known as psychoactive drugs or "party drugs" Cheung & Cheung [17]. Since 1990s, some European countries and the U.S. have seen the rising popularity of psychoactive drugs among youth Parker et al. [18]. During the last decade, there has been a rapid proliferation of new psychoactive substances across the world.

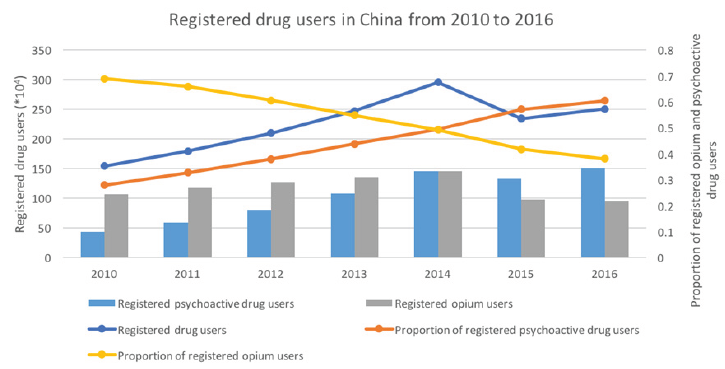

In China, the data of registered synthetic drug users (108,300) firstly appeared in the Annual Report on Drug Control in 2004. At that time, synthetic drug user only accounted for 9.5% among all registered drug users China National Narcotics Control Commission [19]. In recent years, Guangdong Province, home to the bulk of China's chemical industry, has become one of the world's biggest methamphetamine manufacturing areas Minter [20]. The sufficient supply also makes the synthetic drugs available at a lower price, which further accelerates the spread of synthetic drugs across all age and social class groups in China. Afterwards, especially from 2011 to 2016, the number of registered synthetic drug users have been growing rapidly in Figure 1. In 2014, the number of registered synthetic drug users firstly exceed that of registered opiates users and continued increasing afterwards. In 2015, the number of registered drug users decreased because it excluded those who have maintained abstinence for more than three years, those who died, and those who have left China China National Narcotics Control Commission [23]. In 2016, the number of registered synthetic drug users reached 1,515,000, almost two times of opiates users China National Narcotics Control Commission [24].

Figure 1: Number of registered drug users in China (China National Narcotics Control Commission [3,8,18,20,21], China Youth Daily [21], Xinhua Net [22]).

Poly-Drug Use: A Long-standing Phenomenon

Poly-drug use is a common phenomenon either among opiates users or synthetic drug users. This is partially because the drug in its pure form is difficult to find in large quantities Opium Organization [25]. According to an epidemiological survey on polydrug abuse conducted in China, 76% of the sampled drug users are poly-drug users and the top-seven drugs include heroin, heroin and diazepam, diazepam, triazolam, marijuana, MDMA, and methadone Fu et al. [26]. Some of them even have tried more than four types of drugs in their lifetime.

Demographic Characteristics of Drug Abusers in China

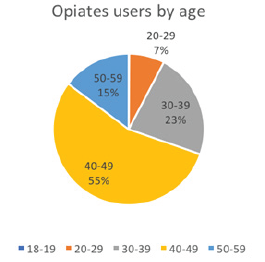

Figure 2: Age distribution of heroin users (Gui [29]).

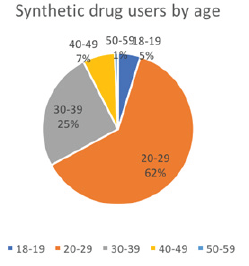

Figure 3: Age distribution of synthetic drug users (Gui [29]).

According to our self-reported survey targeting at institutionalized drug users in Guizhou Province in 2016, heroin users and synthetic users are greatly different in terms of age (Figure 2 & 3). Among heroin users, 40-49 group accounts for 55%. On the contrast, among synthetic drug users, 20-29 group is the dominant group (about 62%). In other words, synthetic users are apparently younger than traditional heroin users [30-33].

Conclusion

As a country with long tradition of drug use, China has witnessed a significant turning point in drug use patterns during last two decades. The synthetic drugs have become the dominant type of drugs in the drug market and it will keep increasing with the worldwide proliferation of psychoactive drugs. Meanwhile, we need to notice that nowadays a considerable number of synthetic drug users in China are poly-drug users and they might try more types of drugs in their lifetime.

References

- BBC (2017) Welsh charities 'see rise in psychoactive drug use'. BBC News.

- SCMP (2017) China's synthetic drug problem growing, government says. SCMP News.

- China National Narcotics Control Commission (2015) Annual report on drug control in China. Office of China National Narcotics Control Commission (NNCC), Beijing, China.

- Li X, Fang Q (2013) Modern chinese legal reform: new perspectives. University Press of Kentucky, USA.

- Dikotter F, Laamann L, Xun Z (2002) Narcotic culture: A social history of drug consumption in China. The British Journal of Criminology 42(2): 317-336.

- Liang B, Lu H, Taylor M (2009) Female drug abusers, narcotics offenders, and legal punishment in China. Journal of Criminal Justice 37(2): 133-141.

- Dupont A (1999) Transnational crime, drugs, and security in East Asia. Asian Survey 39(3): 433-455.

- Liang B, Lu H, Taylor M (2009) Female drug abusers, narcotics offenders, and legal punishment in China. Journal of Criminal Justice 37(2): 133141.

- China National Narcotics Control Commission (2008) Annual report on drug control in China. Office of China National Narcotics Control Commission (NNCC), Beijing, China.

- Tanner MS (2011) Trafficking golden crescent drugs into western China: An analysis and translation of a recent chinese police research article (No. D0024357. A2). Center for Naval Analyses.

- Zhang Y (2012) Asia, international drug trafficking, and us-china counter narcotics cooperation. Brookings Institution, Center for Northeast Asian Policy Studies.

- China Daily (2009) Xinjiang targets drug trafficking. CHINA.ORG.CN.

- Regulations on the People's Republic of China on Administrative Penalties for Public Security (1987) Laws of the People's Republic of China.

- Measures for the Control of Narcotic Drugs (1987).

- Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress on the Prohibition Against Narcotic Drugs (1990).

- Zhao D, Zhao CZ, Liu YH, An YQ, Liu ZM (2003) Drug abuse and HIV situation in China. Chinese Journal of Drug Dependence 12(4): 246-251.

- Cheung NW, Cheung YW (2006) Is Hong Kong experiencing normalization of adolescent drug use? Some reflections on the normalization thesis. Subst Use Misuse 41(14): 1967-1990.

- Parker HJ, Aldridge J, Measham F (1998) Illegal leisure: The normalization of adolescent recreational drug use. Health Education Research 14(5): 707-708.

- China National Narcotics Control Commission (2004) Annual report on drug control in China. Office of China National Narcotics Control Commission (NNCC), Beijing, China.

- Minter A (2015) China's growing meth addiction.

- 21. China Youth Daily (2014) Registered drug users in China doubled in past five years and youth under 35 years old accounted for more than 70 percent. China News.

- Xinhua Net (2011) Registered synthetic drug abusers accounted for 30 percent among all registered abusers in China. Official Website of The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China.

- China National Narcotics Control Commission (2016) Annual Report on Drug Control in China. Office of China National Narcotics Control Commission (NNCC), Beijing, China.

- China National Narcotics Control Commission (2017) Annual Report on Drug Control in China. Office of China National Narcotics Control Commission (NNCC), Beijing, China.

- Opium Organization. (2017) Is Polydrug Abuse Common Among Opium Addicts? Opium.

- Fu XB, Lin P, Li JH, Wang Y, Zhong WL, et al. (2004) Epidemiological survey on poly-drug abuse in intravenous drug users in Guangdong Province. South China Journal of Preventive Medicine 30(11): 8-11.

- Deng Q, Tang Q, Schottenfeld RS, Hao W, Chawarski MC (2012) Drug use in rural China: a preliminary investigation in Hunan Province. Addiction 107(3): 610-613.

- He Z, Luo W, Qiu Z, Qiu H (2004) The survey and analysis of the causes of drug abusing. Chinese Journal of Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment 10(1): 20-23.

- Gui W (2005) A study of female drug offenses. Faxue Shiyong 7: 40-43.

- Wang Y (2008) A study of female drug users in Zhejiang province. Journal of People's Public Security University of China 4(6): 149-156.

- Chu TX, Judith AL (2005) Injection drug use and HIV/AIDS transmission in China. Cell Res 15(11): 865-869.

- Heimer K, Coster SD (1999) The gendering of violent delinquency. Criminology 37(2): 277-318.

- Decision of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress on the Prohibition Against Narcotic Drugs (1990).

© 2017 Yunran Zhang, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)