- Submissions

Full Text

Examines in Marine Biology & Oceanography

Marine Regional Parks and Cultural Heritage: A Potential Meeting in the Calabria Coastal Region (Southern Italy)

Nicola Cantasano1* and Federico Boccalaro2

1National Research Council of Italy, Institute for Agricultural and Forestry Systems in the Mediterranean, Italy

2AIPIN Lazio, Section of Italian Association for Soil Bioengineering, AIPIN, Member of EFIB, European Federation of Soil Bioengineering, Italy

*Corresponding author: Nicola Cantasano, National Research Council of Italy, Institute for Agricultural and Forestry Systems in the Mediterranean, I.S.A.Fo. M.S.S. Rende (CS), Via Cavour 4/6, 87036 Rende (Cs), Italy

Submission: February 12, 2025;Published: March 03, 2025

ISSN 2578-031X Volume7 Issue 4

Abstract

The marine regional parks in Calabria were established to protect some of the most important coastal seawaters of the region, at biological and environmental levels. At the same time, these protected areas were established to value the Zones of Special Conservation located along the regional coastline. Indeed, Calabria coastal regions hold a rich cultural heritage made of towers, castles, churches and water mills located in seaboard areas within the coastal landscape of marine regional parks. In this way, there is a tight connection between natural and cultural goods widespread in littoral areas. However these natural and cultural goods are, actually, threatened by coastal erosion and by human pressures, leading to the decay and, in some cases, to the disappearance of these resources. To solve this issue, it is necessary to protect such heritage, including all the natural and cultural goods still existing in Calabria coastal regions. The paper highlights these close relationships within a process of an effective Integrated Coastal Zone Management.

Keywords:Calabria; Marine regional parks; Natural resources; Cultural heritage; Integrated coastal zone management

Introduction

Coastal regions keep up economic, social and environmental values for mankind [1,2]. This transitional landscape, between land and sea, extended from coastal plains to the outer limits of continental shelf [3], provides the food resources required for human well-being through commercial fishing and aquaculture. Indeed, in the landward sides of seaboard areas there are many industrial and agricultural activities very useful for the social and economic development of local people. Finally, littoral stretches hold an important and increasing tourist flow and, above all, house about the 70% of world population [4]. The transboundary nature of coastal seas needs for a Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) program connecting land to sea into an Integrated Coastal Zone Management process (hereafter, ICZM), as highlighted by European Union (EU), through the MSP Directive, ICZM Protocol and other international conventions [5,6]. At the same time, this integrated approach is moving towards a more effective Ecosystem-Based Management (EBM) of coastal areas [7], melting cultural heritage and coastal ecosystems into a social and ecological pattern [8]. However, the connection Man-Sea has been always a potential source of conflictual relationships, increasing in these last decades. So, mankind has overexploited the natural resources well beyond the carrying capacity of coastal system. In Italy, the decay of littoral areas is mainly caused by human pressures connected to terrestrial driving forces affecting coastlines. In time, the rough development of socio-economic activities has affected coastal regions through maritime infrastructures, overfishing, discharges of urban wastes, marine pollution and shifts in the structure of marine ecosystems. All these topics are clearly related to an uncontrolled coastal development causing the disappearance of some marine habitats.

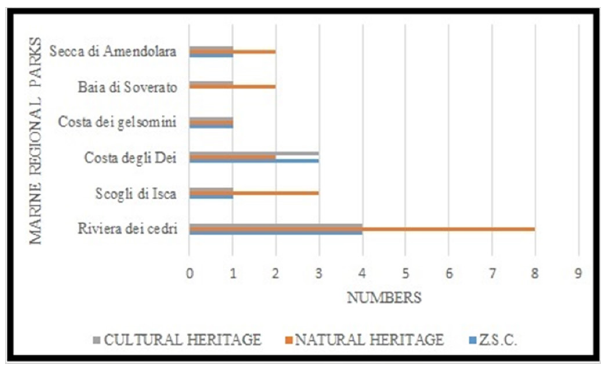

The intensive use of coastal region, its rough urbanization, without any restrictions and the overexploitation of marine resources, have been factors unbalancing marine ecosystems. Also, pollution processes of seawaters by industrial and domestic origins make an important role affecting coastal habitats [9]. As regards the national cultural heritage, there are a total of 14.000 archaeological and architectural goods exposed to hydrological and geo-morphological risks while 28.483 sites are potentially subjected to flooding events. Globally, the 33% of these historical goods are subjected to the risk of coastal erosion [9]. In the Calabria region, there are six Marine Regional Parks (hereafter, MRP), established with regional laws between 2008 and 2022 and managed by MRP regional board. These protected areas cover a global marine surface of 17390.58ha, concerning the most valuable coastal regions at biological and environmental levels. These seaward areas are overlapped with ten marine Zones of Special Conservation (hereafter, ZSC), representing an important hotspot for marine biodiversity. Side by side, Calabria coastal regions hold a rich cultural heritage, made by 63 cultural heritage sites, [10], distinguished in castles, churches, towers, fishponds, water mills and other historical goods widespread along the regional coastline, where still exists a rich cultural heritage located in seaboard areas, as in other Italian littoral regions [11]. In this way, Calabria becomes an ideal model where lives altogether, along its coastline, a great richness of natural and cultural goods, all connected in the same coastal region. Therefore, it could be hoped to melt scientific, policy and administrative levels into a new kind of ICZM planning [12], so to merge the environmental value of natural goods with the presence of human being [13]. In this way, natural and cultural values, joining land and sea, should be strictly connected to play an important role for the sustainable development of coastal regions. This study aims to analyse the connections between natural and cultural goods within a process of ICZM in Calabria seaboard areas.

Study Area

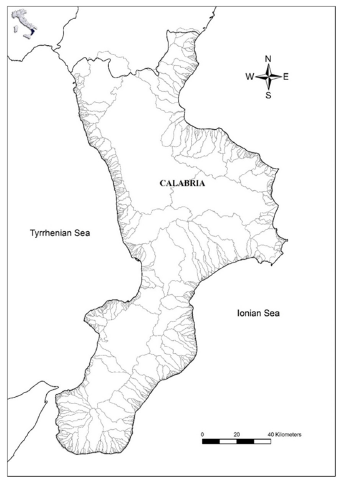

Calabria is the southernmost tip of Italy, being the hill of Italian peninsula. The regional coastline shows an overall extension of 715.7Km., as about 9.7% of the whole Italian littoral boundary. Calabria landscape is formed by uplands and hilly areas, as respectively 42% and 49% of the regional territory, while only the 9% of its continental landward is made by plains [14]. This region, at the centre of Mediterranean Sea, is washed, on its western side, by the Tyrrhenian Sea for a coastline length of 242Km., while the eastern side is surrounded by the Ionian Sea along 474Km. length. In particular, the western seaside of the region is in poor conditions and the 52% of its coastline can be valued at high risk for the realization, close to the beaches, of coastal buildings related to urban settlements. It follows that erosive processes can cause remarkable losses of human infrastructures while the works of coastal defence cover just 37Km. of Tyrrhenian coastline. In the Ionian seaboard areas, the erosive crisis has been less extended and it appears more related to late times. In this way, coastal stretches at high risk, as the 40% of sandy beaches, are located in the southern area, where these littoral regions, strongly hardened by urbanization and by road infrastructures are protected by defensive works for about 22km. Along the north-eastern coastal zone of Calabria, the conditions are more stable and just the 30% of sandy beaches are at low risk of erosion for the poor development of urban settlements [15]. The geological pattern of the regional coastline is characterized by rocky coasts, as the 55% of the whole while sandy beaches cover the 45% of the regional coastline [16]. The two seasides of Calabria are strictly connected by a complex network of fluvial catchments, represented by 36 main basins, 75 secondary catchments and 591 little ones [11], as established by the former Italian Hydrographic Service, recently updated on a regional scale by the Regional Agency for Environmental Protection (ARPACAL, http://www.cdf. calabria.it). So, the continental landscape of the region is mainly characterized, by small catchment areas where the river channel slopes reach values up to 20%, favouring fast water flows with a high solid transport load [17-19]. In such conditions, the drainage network shows deep incisions exposed to landslides and flooding events [20-23]. This hydrographic outline is extended in the continental regional landscape, where the widespread presence of riverine basins could be compared with the blood vessels of a human cardiovascular system (Figure 1).

Figure 1:Geographic map and hydrographic network of Calabria.

The mountain pattern of Calabria makes it as one of the rainiest regions in Italy with an annual rainfall of 1.151mm/year against a national trend of 970mm/year [24,25]. In particular, short and heavy rainfalls occur frequently on the Calabria Tyrrhenian coasts reaching values up to 200mm cumulated in just three hours [26]. In this climate regime, flooding events can, often, affect the courses of streams and riverine outlets, causing damages and economic losses in urbanized littoral areas [19,26]. Finally, Calabria is an important cultural region, representing a crossroad of different and various civilizations for the historical presence of Greek and Roman dominations, leaving a lot of archeological sites. Afterwards, the region was dominated by Byzantines and later by Lombards and Normans with their anthropological and historical remnants [27], enriching the Calabria cultural heritage.

Materials and Methods

In this study, it is necessary to analyse the geographic distribution of MRP and, at the same time, the spatial pattern of cultural heritage sites, highlighting their relationships. This effort aims to develop an integrated approach towards the improvement of natural and cultural goods. All the data, regarding MRP, have been drawn by informative layers released by the Calabria MRP regional board at https://www.parchimarinicalabria.it. Side by side, the information regarding cultural heritage sites have been deduced by literature [28,29]. Indeed, the locations of MRP, ZSC and historical goods have been stated through topographic maps edited by Calabria Region on 2016 year. In particular, as regards the cultural sites widespread along the Calabrian coasts, it has been considered only the historical goods within an area of three hundred meters from the regional coastline. Finally, it has been highlighted the great richness of natural and cultural values still existing in the two islands of Cirella and Dino along the Thyrrennian Calabria coast, according to the guidelines established by the article 12 of ICZM protocol. Finally, all the data have been processed through Geographic Information System (Qantum GIS 17.0) [30], overlapping the cartographic elements with digital images derived by Google Earth Maps on 2024 year.

Results

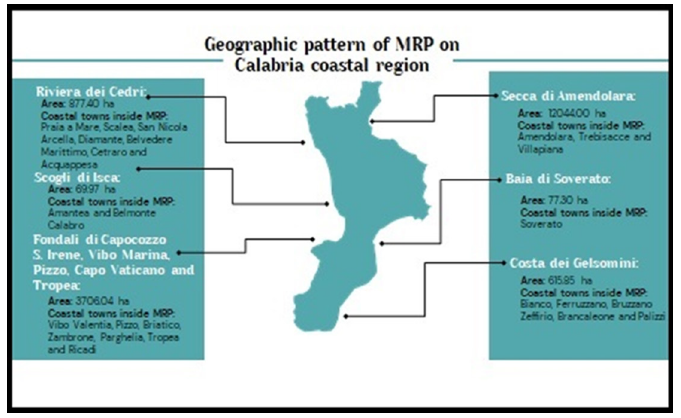

Calabria region holds six MRP for a total surface area of 17330.58ha. of which Rivera dei Cedri, Scogli di Isca and Fondali di Capocozzo, S.Irene, Vibo Marina, Pizzo, Capo Vaticano and Tropea, (named also Costa degli Dei), are located along the western Tyrrhenian coast of the region, covering 4653.42ha. On the eastern coastline of Calabria, washed by Ionian Sea, there are other three MRP named Costa dei Gelsomini, Baia di Soverato and Secca di Amendolara for a whole surface area of 12737.16ha. (Figure 2). All these MRP, established by Calabria Region and managed by its regional board, are overlayed with ten ZSC inserted into Natura 2000 network and located on seaboard and marine areas within 300 from the regional coastline. In this way, ZSC are established to protect some endangered species [31] and priority habitats, as Posidonia oceanica meadows (Figure 3) within the Red List of International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) [32].

Figure 2:Geographic distribution of Calabria MRP.

Figure 3:Posidonia oceanica meadow in the coastal seawaters of “Riviera dei Cedri” MRP.

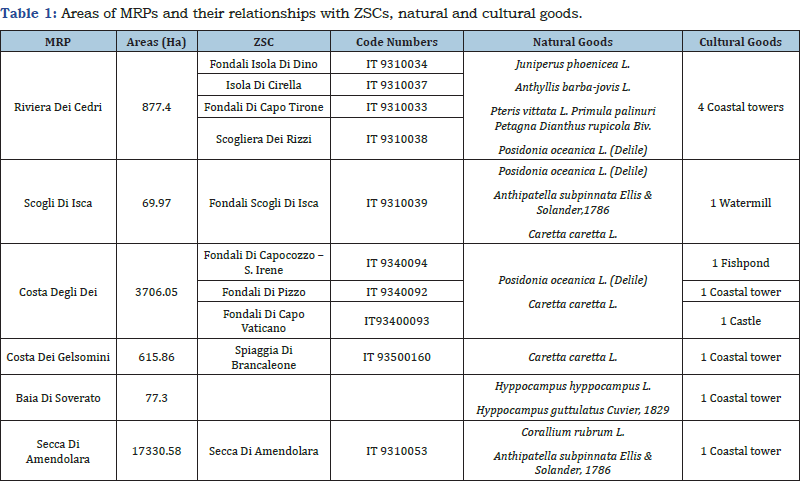

Finally, this study highlights the presence of some important cultural goods, distinguished in 8 coastal towers, 1 water mill, 1 fishpond and 1 castle, located into MRPs or in their neighbourhood (Table 1). Among archeological sites, coastal towers are the most widespread cultural goods along the regional coastline, as the case of “Torre di Fiuzzi” and “Torre di Crawford” located in MRP “Rivera dei Cedri” and close to the regional coastline (Figure 4). With the purpose to highlight the integration between cultural heritage sites, priority habitats and MRP within ICZM process, a case study, located in the island of Cirella, has been chosen along the Calabria Tyrrhenian coast. This choice aims to hihlight that both natural and cultural goods could be integrated in the same landscape unit./

Table 1:Areas of MRPs and their relationships with ZSCs, natural and cultural goods.

Figure 4:The coastal towers “Torre di Fiuzzi”, on the left,, and “Torre di Crawford”, on the right of the figure, both located in MRP “Riviera dei Cedri”.

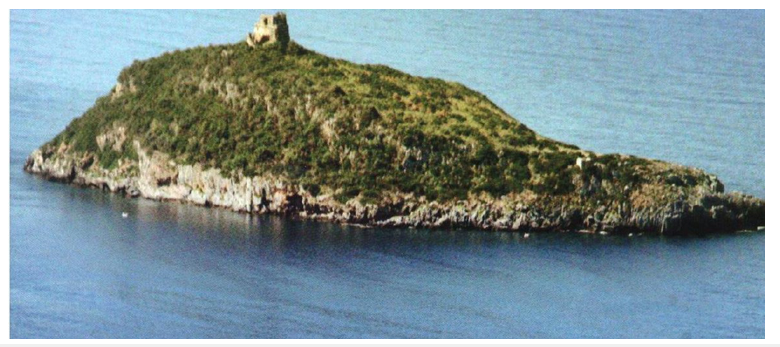

A case study: The island of Cirella

The island of Cirella (39°69’88”N, 15°80’16”E) is located along the Calabria western seaside between the coastal villages of Cirella (Cs) and Diamante (Cs) (Figure 5). This islet, inserted in the MRP “Riviera dei Cedri”, is an important ZSC characterized by a typical Mediterranean vegetation and by the suggestive appearance of a typical coastal tower. So, the island shows a clear overlapping between natural and cultural goods. In the island, there are many important habitat types such as: 1240 Vegetated sea cliffs of the Mediterranean coasts with endemic Limonium spp.; 5330 Thermo- Mediterranean and pre-desert scrub; 8210 Calcareous rocky slopes with chasmophytic vegetation; 9320 Olea and Ceratonia forests and, at last, the priority Habitat 6220 Pseudo-steppe with grasses and annuals of the Thero-Brachypodietea. In the inland coastal seawaters, a large meadow of Posidonia oceanica (Linnaeus) Delile, as priority Habitat 1120, extends around the island. As well, the cultural heritage is represented by a log-pyramidal tower on a square basis. This important archeological site, actually in ruins, was built in sixteenth century within a military system able to defend coastal people against barbarian invasions coming from the sea [33]. To highlight the tight connections between natural and cultural goods, it is possible to observe in the marine areas, just in front the island, some clay materials and archeological submerged ruins dated back to the third century b.C. [34]. So, also in coastal seawaters there is a remarkable melting point between marine ecosystems and archeological heritage.

Figure 5:The island of Cirella with its coastal tower on the top.

Discussion

The resulting data highlight the close relationships between

cultural heritage sites, natural goods and Natura 2000 network in

Calabria MRP (Figure 6). However, in a changing coastal landscape,

threatened by coastal erosion and by an increasing human

pressures, a lot of species, some priority habitats and many cultural

goods are actually at risk. So, in a transitional and sensitive area,

it is necessary to protect natural and historical resources at both

sides of this frontier. A potential solution to protect and value such

heritage for future generations is the application of ICZM process,

including all the natural and cultural goods still existing in Calabria

coastal regions (Figure 7). The conservation of natural and cultural

goods in coastal regions is a key issue in the process of an effective

Integrated Coastal Zone Management [35]. In the implementation

of ICZM, according to a new kind of global approach, it should be

applied, for biodiversity protection and cultural conservation, the

following guidelines deduced by scientific literature [36,37]:

a. Identification of the most valuable marine and terrestrial areas

deserving protective measures.

b. Use of legal means for a careful zoning of marine reserves and

for action plans in Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

c. Realization of a regional planning pattern for the protection

and the valorization of cultural and natural goods regarding

coastal regions.

d. Support a policy-making process for an effective management

of seaboard areas.

Figure 6:Pie chart showing the connections between cultural and natural goods within Natura 2000 network.

Figure 7:The pattern of ICZM process and the connections between natural and cultural goods in Calabria MRP.

In particular, as regards the regional cultural heritage, the

Italian Commision of UNESCO [38] suggested to national and local

authorities to realize standing and protective actions, ensuring

future generations to enjoy all the natural and cultural goods both

of statal and regional governance. In this way, there are some

cornerstones for an effective protection of coastal archaeological

sites, as follows [39]:

a) The analysis of coastal archaeological sites, valued in physical,

hydrological and geological terms, aims to a natural beach

nourishment, to the whole reclamation of coastal zones and to

an effective stability of coastlines.

b) It is necessary to restore coastal ecosystems so to protect their

biocenosis as regards, in particular, the increasing shifts of

weather and sea conditions, affecting coastal stretches.

c) The operative protocols, before any coastal care must be

clearly established to avoid indefinite operations of “hydraulic

cleaning” in protected areas.

d) In every coastal stretch, subjected to conditions of geological

instability, must be planned and timely applied interventions

of Soil Bioengineering.

e) The promotion of recovery actions, able to value coastal

landscape and cultural identity, must be realized through

planned operative measures directed towards an effective risk

prevention and a global landscape valorization, meeting the

growing tourist demand in coastal regions.

So, littoral areas could become cultural expression, merging natural values with human well-being [40]. The main theme of this new kind of landscape pattern, based on ICZM process, develops from the protection of some target species to a novel approach able to extend its spatial scale, like a dot, to a global vision based on the principle of “wide areas” [41]. In this way, it is suggested to connect in MRP the cultural goods, still existing along the regional coastline, with Natura 2000 network, so to implement ICZM process in the Calabria region.

Conclusion

This study highlights the need to melt in the same coastal landscape all the historical and natural goods, integrating the protection of marine biodiversity with the conservation and the improvement of cultural heritage sites. So, it is necessary to strengthen scientific, social and policy actions to include cultural and natural resources, linking the landward and seaward sides of coastal regions. This integrated approach, for a sound management of seaboard areas, has been suggested, also, in other littoral regions located in Belgium, United Kingdom, Israel and South Africa [42,43]. In the Mediterranean basin, similar studies have been conducted in some coastal landscapes [44,45]. These efforts are, however, very far from an effective implementation because cultural heritage sites are intangible, without economic values and often neglected in ecosystem services [46]. Therefore, it is necessary to adopt a more inclusive and participatory approach to better understand the tight relationships between cultural and natural goods. In Calabria coastal regions, marine and terrestrial environments are strictly connected in the same landscape unit, melting priority habitats, target species and cultural heritage sites in a whole system. However, the loss of marine biodiversity and the decay of some historical goods could produce negative effects, in the long run, for future generations. To reverse this trend, it could be suggested a new kind of environmental tourism in Calabria MRP appreciating all the natural and cultural resources on the landward and seaward sides of the region within an effective ICZM process for the social and economic development of local people. In conclusion, Calabria could represent a new kind of regional pattern for the integration of natural and cultural goods in the same coastal landscape.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Raffaele Greco, Director of the Regional Local Board of MRP and Antonino Mancuso, as official member of MRP, for the digital images of the Marine Regional Parks released by Calabria Region.

References

- Weide JV (1993) A system view of Integrated coastal management. Ocean and Coastal Management 21(1-3): 129-148.

- Clark JR (1997) Coastal zone management for the new century. Ocean and Coastal Management 37(2): 191-216.

- Agardy MT (1993) Accommodating ecotourism in multiple use planning of coastal and marine protected areas. Ocean and Coastal Management 20(3): 219-239.

- Ray GC (1976) Critical marine habitats. IUCN Publ, 37.

- Barale V, Özhan E (2010) Advances in integrated coastal management for the Mediterranean & Black Sea. Journal of Coastal Conservation 14: 249-255.

- Fernandes ML, Sousa LP, Lillebø AL, Alves FL (2013) Establishment of guidance framework for cross-border maritime spatial planning. In: proceeding of the TWAM, 2013. International Conference & Worksohps.

- Kyvelou S (2017) Maritime spatial planning as evolving policy in Europe: Attitudes, challenges and trends. EQPAM 6(3): 1-14.

- Virapongse A, Brooks S, Metcalf EC, Zedalis M, Gesz J, et al. (2016) A socio-ecological system approach for environmental management. Journal of Environmental Management 178: 83-91.

- Ishpra Environmental Data Yearbook - 2018 Edition (2019) Ishpra, State of the Environment, 84/2019, Italy.

- Accardo G, Altieri A, Cacace C, Giani E, Giovagnoli A (2002) Risk map: A project to aid decision-making in the protection, preservation and conservation of Italian cultural heritage. In: Conservation Science 2002, Proceedings from the conference held in Edinburgh, Archeotype Publications, UK, pp. 44-49.

- Cantasano N, Caloiero T, Pellicone G, Aristodemo F, Marco A, et al. (2021) Can ICZM contribute to the mitigation of erosion and of human activities threatening the natural and cultural heritage of the coastal landscape of Calabria? Sustainability 13(3): 1122.

- Vallega A (2001) Focus on integrated coastal management - comparing perspectives. Ocean and Coastal Management 44(1-2): 119-134.

- Cantasano N, Pellicone G, Ietto F (2017) Integrated coastal zone management in Italy: A gap between science and policy. Journal of Coastal Conservation 21: 317-325.

- Viceconte G (2004) Calabria, the water system. Notebook no. 7. Ministry of infrastructure and transport. Italy, pp. 1-34.

- Naveh Z, Lieberman AS (1994) Landscape ecology. Theory and Applications, (2nd edn), Springer Publishers, USA, pp. 1-360.

- Boccalaro F (2002) Coastal defense and naturalistic engineering. Italy, pp. 577.

- Ietto F, Perri F (2015) Flash flood event (October 2010) in the Ginzolo Catchment (Calabria, Southern Italy). Rendiconti Online Società Geologica Italiana 35: 170-173.

- Ietto F, Perri F, Fortunato G (2015) Lateral spreading phenomena and weathering processes from the Tropea area (Calabria, Southern Italy). Environmental Earth Sciences 73: 4595-4608.

- Antronico L, Borrelli L, Coscarelli R (2017) Recent damaging events on alluvial fans along a stretch of the Tyrrhenian coast of Calabria (Southern Italy). Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment 76: 1399-1416.

- Calcaterra D, Parise M (2010) Weathering as a predisposing factor to slope movements: An introduction. Geological Society of London, Special Publication 23: 1-4.

- Conforti M, Pascale S, Robustelli G, Sdao F (2014) Evaluation of prediction capability of the artificial neural networks for mapping landslide susceptibility in the Turbolo River catchment (Northern Calabria, Italy). Catena 113: 236-250.

- Ietto F, Perri F, Cella F (2016) Geotechnical and landslide aspects in weathered granitoid rock masses (Serre Massif, southern Calabria, Italy). Catena 145: 301-315.

- Ietto F, Perri F, Cella F (2018) Weathering characterization for landslides modeling in granitoid rock masses of the Capo Vaticano promontory (Calabria, Italy). Landslides 15(1): 43-62.

- Petrucci O, Chiodo G, Caloiero D (1996) CNR-IRPI 1374. In: Rubbettino Arti Grafiche (Eds.), Flood events in Calabria in the Decade 1971-1980. Soveria Mannelli, Italy.

- Buttafuoco G, Caloiero T, Coscarelli R (2007) Evaluation of rainfall trends in Calabria. In: Carli B (Ed.), Climate and climatic changes: Research activities of the CNR. Italy, pp. 237-240.

- Ietto F, Cantasano N, Salvo F (2014) The quality of life conditioning with reference to the local environmental management: A pattern in Bivona country (Calabria, Southern Italy). Ocean and Coastal Management 102: 340-349.

- Placanica A (1999) History of Calabria: From antiquity to the present day. Italy.

- Bevilacqua F (1993) Calabria Verde. pp. 263.

- Mellow F (2018) Archaeological guide of Calabria Santike. Rosario Rubbettino Publishers, Italy, pp. 750.

- Hugentobler M (2008) Quantum GIS. In: Shekhar S, Xiong H (Eds.), Encyclopedia of GIS. Springer Publishers, USA, pp. 935-939.

- Annual Report of the Secretariat (2002) CITES Convention on International Trade in endangered species of wild fauna and flora. pp. 1-24.

- Pergent G, Semroud R, Djellouli A, Langar H, Duarte C (2010) Posidonia oceanica. In IUCN Red List.

- Carafa R, Calderazzi A (1999) Fortifications of Calabria. Recognition a Shedatura in Dela Territory. Mapograph Edn, Italy.

- Mollo F (2018) Archaeological guide of Calabria Santike. Rubbettino Edn, Italy, 1-750.

- Goodhead T, Aygen Z (2007) Heritage management plans and integrated coastal management. Marine Policy 31(5): 607-610.

- Bin C, Weiwei Y, Senlin Z, Jinkeng W, Jinlong J (2009) Marine biodiversity conservation based on integrated coastal zone management (ICZM). A case study in Quanzhou Bay, Fujian, China. Ocean and Coastal Management 52(12): 612-619.

- Agardy T, Notarbartolo GS, Christie P (2011) Mind the gap: Addressing the shortcomings of marine protected areas through large scale marine spatial planning. Marine Policy 35(2): 226-232.

- Annual Report (2019) National Commissions for UNESCO. Italy, pp. 206.

- Marenostrum-Archivesnub of Italy (2019) Manifesto Titled Gatin Ekakapatibil Dei City Archeologici Castiari. Italy, pp. 1-17.

- Vallega AA (1993) A conceptual approach to integrated coastal management. Ocean and Coastal Management 21(1-3): 149-162.

- Gambino R (2004) Conservation and planning of large area systems. In Proceedings of the National Conference WWF Italia ONG ONLUS 2004; Ecoregions and ecological networks, Italy, pp. 27-28.

- Khakzad S, Pieters M, Van Balen K (2015) Coastal cultural heritage: A resource to be included in integrated coastal zone management. Ocean and Coastal Management 118: 110-128.

- Rivers N, Truter HJ, Strand M, Jay S, Portman N, et al. (2022) Shared visions for marine spatial planning: Insights from Israel, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Ocean and Coastal Management 220: 106069.

- Makhzoumi J, Pungetti G (1999) Ecological landscape design and planning: The Mediterranean context. Spon-Routledge Publishers, UK.

- Vogiatzakis IN, Pungetti G, Mannion AM (Eds.), (2008) Mediterranean Island landscapes. Natural and cultural approaches. Springer Publishers, UK, pp. 1-369.

- Strand M, Rivers N, Snow B (2023) The complexity of evaluating, categorizing and quantifying marine cultural heritage. Marine Policy 148: 105449.

© 2025 Nicola Cantasano. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and build upon your work non-commercially.

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Based on a work at www.crimsonpublishers.com.

Best viewed in

.jpg)

Editorial Board Registrations

Editorial Board Registrations Submit your Article

Submit your Article Refer a Friend

Refer a Friend Advertise With Us

Advertise With Us

.jpg)

.jpg)

.bmp)

.jpg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.png)